Soviet involvement in regime change

Soviet involvement in regime change has entailed both overt and covert actions aimed at altering, replacing, or preserving foreign governments.

During World War II, the Soviet Union helped overthrow many Nazi Germany or imperial Japanese puppet regimes, including in East Asia and much of Europe. Soviet forces were also instrumental in ending the rule of Adolf Hitler over Germany.

In the aftermath of World War II, the Soviet government struggled with the United States for global leadership and influence within the context of the Cold War. It expanded the geographic scope of its actions beyond its traditional area of operations. In addition, the Soviet Union and Russia have interfered in the national elections of many countries. One study indicated that the Soviet Union and Russia engaged in 36 interventions in foreign elections from 1946 to 2000.[1][2][3]

The Soviet Union ratified the UN Charter in 1945, the preeminent international law document,[4] which legally bound the Soviet government to the Charter's provisions, including Article 2(4), which prohibits the threat or use of force in international relations, except in very limited circumstances.[5] Therefore, any legal claim advanced to justify regime change by a foreign power carries a particularly heavy burden.[6]

1914–1941: World War I, the Revolution, the Civil War, and Interwar period

1918: Finland

Finland has been an autonomous part of the Russian Empire for a century. They had been slowly losing their autonomy under them, however that ended with the February Revolution in 1917. This caused Finland to question what its role should be now and if Finland should be independent. The conservatives and Socialists in Finland started politically fighting.[7] The social democrats took some power with "Law of Supreme Power" while Leftists tried to start a revolt which failed.[8] After losing the October 1917 Finnish Election the labor movement was radicalized leftward against moderate politics.[9] After the October Revolution the Bolsheviks took control of much of Russia and signed and armistice on December 7, 1917.[10] As that was happening Finland's parliament was agitating for independence. On December 4, 1917 the Senate introduced Finland's Declaration of Independence and it was soon adopted by Parliament on December 6, 1917. The Social Democrats and Socialists in the country opposed because they wanted to submit their own Declaration. In the end they went to Lenin to ask for permission to go along with it.[11] Lenin had thought that independent nations would have their own Proletariat revolutions and unite with Russia later. The Bolsheviks were focused on defeating the White Army in the Russian Civil War, however they were interested in retaking control of those former territories whether annexing them outright, or funding other leftists in those countries to take and perhaps unite with Russia later on.[12] Finland's short lived civil war would become an example of the latter.

After Finland declared independence tensions between the Left and Right only got worse. In January 1918 both groups started making defensive movements and countering one another.[13] On January 12, 1918 the Finnish Parliament passed a law allowing the Senate to establish order with an army lead by former Finnish Russian general Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim.[14] Tensions boiled up until the leftists mobilized their forces on January 27, 1918 and so the civil war began.[15][16] This soon saw the formation of the Red Army, representing the left, and the White Army, representing the right. The White Army has the support of the German Empire, who wanted to establish a Finnish puppet monarchy.[17] The Red Army formed the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic and were supported by the Bolsheviks. While they were leftists the Red Army were ideologically Democratic Socialists not Bolsheviks, though there were a few Finnish Bolsheviks who wanted annexation.[18] As well the Finnish Red Army were against reuniting with Russia when they won and this caused strife between the both of them. As well Germany and the Bolsheviks were currently negotiating in Brest-Livtosk in order to end the war on the Eastern Front. The Germans leveraged the negotiations in order to get the Bolsheviks to be less involved in the war. the Bolsheviks had promised when they came to power to get out of World War I. They were eventually successful at that and on March 3, 1918 the Treaty of Brest-Livtosk was signed between the German Empire where the Bolsheviks exited the World War I while they handed over most of the eastern territory of the former Russian Empire, including Finland.[19] While some support remained the Whites ended up winning the civil war on May 15, 1918. Despite that the Germans would lose rule over Finland after they lost World War I.

1921-1924: Mongolia

The Mongolian Revolution of 1911 saw Mongolia declare independence from the Qing Dynasty in China, ruled by Bogd Khan. In 1912, the Qing Dynasty collapsed into the Republic of China. In 1915, Russia and China signed the Kyatha agreement, making it autonomous. However, when the Russian Civil War broke out, China, working with Mongolian aristocrats, retook Mongolia in 1919. At the same time the Russian Civil War raged on and the White Army were, by 1921, beginning to lose to the Red Army. One of the commanders, Roman Ungern Von Sternberg, saw this and decided to abandon the White Army with his forces. He led his army into Mongolia in 1920, and conquered it completely by February 1921, putting Bogh Khan back into power.[20][21]

The Bolsheviks had been worried about Sternberg and, at the request of the Mongolian People's Party, invaded Mongolia in August 1921 helping with the Mongolian Revolution of 1921. The Soviets moved from many directions and captured many locations in the country. Sternberg fought back and marched into the USSR but he was captured and killed by the Soviets on September 15, 1921. The Soviets kept Bogd Khan in power, as a constitutional monarch, hoping to keep good relations with China, while continuing to occupy the country. However, when Bogd Khan died in 1924, the Mongolian Revolutionary government declared that no reincarnations shall be accepted and set up the People's Republic of Mongolia which would exist in power until 1992.[22]

1929: Tannu Tuva

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty, the province of Tannu Uriankhai became independent, and was then made a protectorate of the Russian empire. During the Russian Civil War, the Red Army created the Tuvan People's Republic. It was located in between Mongolia and the USSR and was only recognized by the two countries.[23] Their Prime Minister was Donduk Kuular, a former Lama with many ties to the Lamas present in the country.[24] He tried to put his country on a Theocratic and Nationalistic path, tried to sow closer ties with Mongolia, and made Buddhism the state religion.[25] He was also resistant to the collectivization policies of the Soviet Union. This was alarming and irritating to Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union's leader.[26]

The Soviet Union would set the ground for a coup. They encouraged the "Revolutionary Union of Youth" movement, and educated many of them at Communist University of the Toilers of the East. In January 1929, five youths educated at the school would launch a coup with Soviet support and depose Kuular, imprisoning and later executing him. Salchak Toka would become the new head of the country. Under the new government, collectivization policies were implemented. A purge was launched in the country against aristocrats, Buddhists, intellectuals, and other political dissidents, which would also see the destruction of many monasteries.[27][28][29][30]

1929: Afghanistan

After the Third Anglo-Afghan War, Afghanistan had full independence from the British Empire, and could make their own foreign relations.[31] Amanullah Khan, the king of Afghanistan, made relations with the USSR, among many other countries, such as signing an agreement of neutrality.[32] There had also been another treaty signed that gave territory to Afghanistan on the condition that they stop Basmachi raids into the USSR.[33] As his reign continued, Amanullah Khan became less popular, and in November 1928 rebels rose up in the east of the country. The Saqqawists allowed Basmachi rebels from the Soviet Union to operate inside the country after coming to power.[34] The Soviet Union sent 1,000 troops into Afghanistan to support Amanullah Khan.[35] When Amanullah fled the country, the Red Army withdrew from Afghanistan.[35] Despite the Soviet withdrawal, the Saqqawists would be defeated later, in 1929.[36]

1934: Xinjiang

In 1934, Ma Zhongying's troops, supported by the Kuomintang government of the Republic of China, were on the verge of defeating the Soviet client Sheng Shicai during the Battle of Ürümqi (1933–34) in the Kumul Rebellion. As a Hui (Chinese Muslim), he had earlier attended the Whampoa Military Academy in Nanjing in 1929, when it was run by Chiang Kai-shek, who was also the head of the Kuomintang and leader of China.[4][5] He was then sent back to Gansu after graduating from the academy and fought in the Kumul Rebellion where, with the tacit support of the Kuomintang government of China, he tried to overthrow the pro-Soviet provincial government first led by Governor Jin Shuren, and then Sheng Shicai. Ma invaded Xinjiang in support of Kumul Khanate loyalists and received official approval and designation from the Kuomintang as the 36th Division.

.svg.png.webp)

In late 1933, the Han Chinese provincial commander General Zhang Peiyuan and his army defected from the provincial government side to Zhongying's side and joined him in waging war against Jin Shuren's provincial government.

In 1934, two brigades of about 7,000 Soviet GPU troops, backed by tanks, airplanes and artillery with mustard gas, crossed the border to assist Sheng Shicai in gaining control of Xinjiang. The brigades were named "Altayiiskii" and "Tarbakhataiskii".[6] Sheng's Manchurian army was being severely beaten by an alliance of the Han Chinese army led by general Zhang Peiyuan, and the 36th Division led by Zhongying,[7] who fought under the banner of the Kuomintang Republic of China government. The joint Soviet-White Russian force was called "The Altai Volunteers". Soviet soldiers disguised themselves in uniforms lacking markings, and were dispersed among the White Russians.[8]

Despite his early successes, Zhang's forces were overrun at Kulja and Chuguchak, and he committed suicide after the battle at Muzart Pass to avoid capture.

Even though the Soviets were superior to the 36th Division in both manpower and technology, they were held off for weeks and took severe casualties. The 36th Division managed to halt the Soviet forces from supplying Sheng with military equipment. Chinese Muslim troops led by Ma Shih-ming held off the superior Red Army forces armed with machine guns, tanks, and planes for about 30 days.[9]

When reports that the Chinese forces had defeated and killed the Soviets reached Chinese prisoners in Ürümqi, they were reportedly so jubilant that they jumped around in their cells.[10]

Ma Hushan, Deputy Divisional Commander of the 36th Division, became well known for victories over Russian forces during the invasion.[11]

Chiang Kai-shek was ready to send Huang Shaohong and his expeditionary force which he assembled to assist Zhongying against Sheng, but when Chiang heard about the Soviet invasion, he decided to withdraw to avoid an international incident if his troops directly engaged the Soviets.[12]

1936–1939: Spain

The newly created Second Spanish Republic became tense with political divisions between right- and left-wing politics. The 1936 Spanish General Election would see the left wing coalition, called the Popular Front, win a narrow majority.[37] As a result, the right wing, known as Falange, launched a coup against the Republic, and while they would take much territory, they would fail at taking over Spain completely, beginning the Spanish Civil War.[38] There were two factions in the war: the right wing Nationalists, which included the Fascist Falange, Monarchists, Traditionalists, wealthy landowners, and Conservatives, who would eventually come to be led by Francisco Franco,[39] and the left wing Republicans, which included Anarchists, Socialists, Liberals, and Communists.[40]

.svg.png.webp)

The Civil War would gain much international attention and both sides would gain foreign support through both volunteers and direct involvement. Both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy gave overt support to the Nationalists. At the time, the USSR had an official policy of non-intervention, but wanted to counter Germany and Italy. Stalin worked around the League of Nations's embargo and provided arms to the Republicans and, unlike Germany and Italy, did this covertly.[41] Arms shipment was usually slow and ineffective and many weapons were lost,[42] but the Soviets would end up evading detection of the Nationalists by using false flags.[43] Despite Stalin's interest in aiding the Republicans, the quality of arms was inconsistent. Many rifles and field guns provided were old, obsolete or otherwise of limited use, (some dated back to the 1860s) but the T-26 and BT-5 tanks were modern and effective in combat.[44] The Soviet Union supplied aircraft that were in current service with their own forces but the aircraft provided by Germany to the Nationalists proved superior by the end of the war.[45] The USSR sent 2,000–3,000 military advisers to Spain, and while the Soviet commitment of troops was fewer than 500 men at a time, Soviet volunteers often operated Soviet-made tanks and aircraft, particularly at the beginning of the war.[46][47][48][49] The Republic paid for Soviet arms with official Bank of Spain gold reserves, 176 tonnes of which was transferred through France and 510 directly to Russia which was called Moscow gold.[50] At the same time, the Soviet Union directed Communist parties around the world to organize and recruit the International Brigades.[51]

At the same time, Stalin tried to take power within the Republicans. There were many anti-Stalin and anti-Soviet factions in the Republicans, such as Anarchists and Trotyskyists. Stalin encouraged NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs) activity inside of the Republicans and Spain.

Catalan communist Andres Nin Perez, socialist journalist Mark Rein, left-wing academic Jose Robles, and others were assassinated in operations in Spain led by many spies and Stalinists such as Vittorio Vidali ("Comandante Contreras"), Iosif Grigulevich, Mikhail Koltsov and, most prominently, Aleksandr Mikhailovich Orlov. The NKVD also targeted Nationalists and others they saw as politically problematic to their goals.[52]

The Republicans eventually broke out into infighting between the communists and anarchists, as both groups attempted to form their own governments. The Nationalists, on the other hand, were much more unified than the Republicans, and Franco had been able to take most of Spain's territory, including Catalonia, an important area of left wing support and, with the collapse of Madrid, the war was over with a Nationalist victory.[53][54]

1939–1940: Finland

On 30 November 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland, three months after the outbreak of World War II, and ended three and a half months later with the Moscow Peace Treaty on 13 March 1940. The League of Nations deemed the attack illegal and expelled the Soviet Union from the organisation.

The conflict began after the Soviets sought to obtain Finnish territory, demanding, among other concessions, that Finland cede substantial border territories in exchange for land elsewhere, claiming security reasons—primarily the protection of Leningrad, 32 km (20 mi) from the Finnish border. Finland refused, so the USSR invaded the country. Many sources conclude that the Soviet Union had intended to conquer all of Finland, and use the establishment of the puppet Finnish-Communist government and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact's secret protocols as evidence of this.[F 8] Finland repelled Soviet attacks for more than two months and inflicted substantial losses on the invaders while temperatures ranged as low as −43 °C (−45 °F). After the Soviet military reorganised and adopted different tactics, they renewed their offensive in February and overcame Finnish defences.

Hostilities ceased in March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland ceded 11 percent of its territory, representing 30 percent of its economy to the Soviet Union. Soviet losses were heavy, and the country's international reputation suffered. Soviet gains exceeded their pre-war demands and the USSR received substantial territory along Lake Ladoga and in northern Finland. Finland retained its sovereignty and enhanced its international reputation. The poor performance of the Red Army encouraged Adolf Hitler to think that an attack on the Soviet Union would be successful and confirmed negative Western opinions of the Soviet military. After 15 months of Interim Peace, in June 1941, Nazi Germany commenced Operation Barbarossa and the Continuation War between Finland and the USSR began.

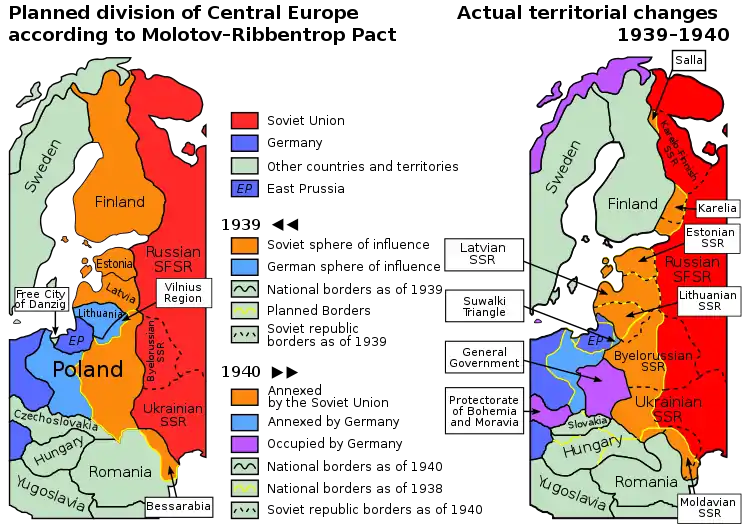

1940: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania

The Soviet Union occupied the Baltic states under the auspices of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in June 1940.[55][56] They were then incorporated into the Soviet Union as constituent republics in August 1940, though most Western powers never recognized their incorporation.[57][58] On 22 June 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union and, within weeks, occupied the Baltic territories. In July 1941, the Third Reich incorporated the Baltic territory into its Reichskommissariat Ostland. As a result of the Red Army's Baltic Offensive of 1944, the Soviet Union recaptured most of the Baltic states and trapped the remaining German forces in the Courland pocket until their formal surrender in May 1945.[59] The Soviet "annexation occupation" (German: Annexionsbesetzung) or occupation sui generis[60] of the Baltic states lasted until August 1991, when the three countries regained their independence.

The Baltic states themselves,[61][62] the United States[63][64] and its courts of law,[65] the European Parliament,[66][67][68] the European Court of Human Rights[69] and the United Nations Human Rights Council[70] have all stated that these three countries were invaded, occupied and illegally incorporated into the Soviet Union under provisions[71] of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. There followed occupation by Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944 and then again occupation by the Soviet Union from 1944 to 1991.[72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79] This policy of non-recognition has given rise to the principle of legal continuity of the Baltic states, which holds that de jure, or as a matter of law, the Baltic states had remained independent states under illegal occupation throughout the period from 1940 to 1991.[80][81][82]

In its reassessment of Soviet history that began during perestroika in 1989, the Soviet Union condemned the 1939 secret protocol between Germany and itself.[83] However, the Soviet Union never formally acknowledged its presence in the Baltics as an occupation or that it annexed these states[84] and considered the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republics as three of its constituent republics. On the other hand, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic recognized in 1991 that the events of 1940 were "annexation[s]".[85] Nationalist-patriotic[86] Russian historiography and school textbooks continue to maintain that the Baltic states voluntarily joined the Soviet Union after their peoples all carried out socialist revolutions independent of Soviet influence.[87] The post-Soviet government of the Russian Federation and its state officials insist that incorporation of the Baltic states was in accordance with international law[88][89] and gained de jure recognition by the agreements made in the February 1945 Yalta and the July–August 1945 Potsdam conferences and by the 1975 Helsinki Accords,[90][91] which declared the inviolability of existing frontiers.[92] However, Russia agreed to Europe's demand to "assist persons deported from the occupied Baltic states" upon joining the Council of Europe in 1996.[93][94][95] Additionally, when the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic signed a separate treaty with Lithuania in 1991, it acknowledged that the 1940 annexation as a violation of Lithuanian sovereignty and recognized the de jure continuity of the Lithuanian state.[96][97]

Most Western governments maintained that Baltic sovereignty had not been legitimately overridden[98] and thus continued to recognise the Baltic states as sovereign political entities represented by the legations—appointed by the pre-1940 Baltic states—which functioned in Washington and elsewhere.[99][100] The Baltic states recovered de facto independence in 1991 during the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Russia started to withdraw its troops from the Baltics (starting from Lithuania) in August 1993. The full withdrawal of troops deployed by Moscow ended in August 1994.[101] Russia officially ended its military presence in the Baltics in August 1998 by decommissioning the Skrunda-1 radar station in Latvia. The dismantled installations were repatriated to Russia and the site returned to Latvian control, with the last Russian soldier leaving Baltic soil in October 1999.[102][103]

1941–1953: World War II, formation of East Bloc, creation of Soviet satellite states, last years of Stalin's rule

The Soviet Union policy during World War II was neutral until August 1939, followed by friendly relations with Germany in order to carve up Eastern Europe. The USSR helped supply oil and munitions to Germany as its armies rolled across Western Europe in May–June 1940. Despite repeated warnings, Stalin refused to believe that Hitler was planning an all-out war on the USSR;[104] he was stunned and temporarily helpless when Hitler invaded in June 1941. Stalin quickly came to terms with Britain and the United States, cemented through a series of summit meetings. The two countries supplied war materials in large quantity through Lend Lease.[105] There was some coordination of military action, especially in summer 1944.[106][107]

As agreed with the Allies at the Tehran Conference in November 1943 and the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Soviet Union entered World War II's Pacific Theater within three months of the end of the war in Europe. The invasion began on 9 August 1945, exactly three months after the German surrender on May 8 (9 May, 0:43 Moscow time). Although the commencement of the invasion fell between the American atomic bombing of Hiroshima, on 6 August, and only hours before the Nagasaki bombing on 9 August, the timing of the invasion had been planned well in advance and was determined by the timing of the agreements at Tehran and Yalta, the long-term buildup of Soviet forces in the Far East since Tehran, and the date of the German surrender some three months earlier; on August 3, Marshal Vasilevsky reported to Premier Joseph Stalin that, if necessary, he could attack on the morning of 5 August. At 11pm Trans-Baikal (UTC+10) time on 8 August 1945, Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov informed Japanese ambassador Naotake Satō that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan, and that from 9 August the Soviet government would consider itself to be at war with Japan.[108]

1940s

1941: Iran

The British Commonwealth and the Soviet Union invaded Iran jointly in 1941 during the Second World War. The invasion lasted from 25 August to 17 September 1941 and was codenamed Operation Countenance. Its purpose was to secure Iranian oil fields and ensure Allied supply lines (see the Persian Corridor) for the USSR, fighting against Axis forces on the Eastern Front. Though Iran was neutral, the Allies considered Reza Shah to be friendly to Germany, deposed him during the subsequent occupation and replaced him with his young son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[109]

1944-1947: Romania

As World War II turned against the Axis and the Soviet Union won on the Eastern Front, Romanian politician, Iuliu Maniu, entered secret negotiations with the Allies.[110] At the time Romania was ruled over by the fascist Iron Guard, with the king as a figurehead. The Romanians had contributed a large number of troops to the front, and had hoped to regain territory and survive.[111] After the Soviets launched a successful offensive into Romania Romanian King Michael I met with the National Democratic Bloc to try and take over the government. King Michael I tried to get the leader of the Iron Guard, Ion Antonescu, to switch sides but he refused. So the King immediately ordered his arrest and took over the government in a coup.[112] Romania switched sides and began fighting against the Axis.[113]

However the Soviet Union still ended up occupying the country, and Stalin still wanted the country to fall under his influence.[113] He ordered the King to appoint Petru Groza, the communist candidate, as the Prime Minister in March 1945.[114][115] At the same time the communist party set up the 1946 Romanian General Election, and fraudulently won it.[116] The King, like with the Iron Guard, only ruled as a figurehead, and the communists took control of the country.[117] In the 1947 the Paris Peace Treaties allowed Red Army troops to continue to occupy the country. As well in 1947 communists forced the King to abdicate and leave the country, and afterwards abolishing the monarchy.[118][119] The communists declared Socialist Republic of Romania in Bucharest, which was friendly and aligned with Moscow. The Soviet occupation of Romania continued until 1958.

1944-1946: Bulgaria

The Kingdom of Bulgaria has originally joined the Axis to gain territory and be protected from the USSR. As well Bulgaria wanted to fend off communists in the country, who had influence in the army. Despite this Bulgaria did not participate in the war very much, not joining in either Operation Barbarosa and refusing to send its Jewish Population to concentration camps.[120] However, in 1943 Tsar Boris III died, and the Axis were starting to lose on the Eastern Front. The Bulgarian government negotiated with the allies and withdrew from the war in August 1944. Despite this they refused to expel the German troops still stationed in the country. The Soviet Union responded by invading the country in September 1944, which coincided with the 1944 coup by communists.[121] The coup saw the communist Fatherland Front take power.[122] The new government abolished the monarchy and executed former officials of the government including 1,000 to 3,000 dissidents, war criminals, and monarchists in the People's Court, as well as exilling Tsar Simeon II.[123][124][125] Following a referendum in 1946 the People's Republic of Bulgaria was set up under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov.[126][127]

1944–1946: Poland

On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, sixteen days after Germany invaded Poland from the west. Subsequent military operations lasted for the following 20 days and ended on 6 October 1939 with the two-way division and annexation of the entire territory of the Second Polish Republic by Germany and the Soviet Union.[128] The Soviet invasion of Poland was secretly approved by Germany following the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939.[129]

The Red Army, which vastly outnumbered the Polish defenders, achieved its targets encountering only limited resistance. Roughly 320,000 Polish prisoners of war had been captured.[130][131] The campaign of mass persecution in the newly acquired areas began immediately. In November 1939 the Soviet government ostensibly annexed the entire Polish territory under its control. Around 13.5 million Polish citizens who fell under the military occupation were made into new Soviet subjects following show elections conducted by the NKVD secret police in the atmosphere of terror,[132][133] the results of which were used to legitimize the use of force. A Soviet campaign of political murders and other forms of repression, targeting Polish figures of authority such as military officers, police and priests, began with a wave of arrests and summary executions.[134][135][136] The Soviet NKVD sent hundreds of thousands of people from eastern Poland to Siberia and other remote parts of the Soviet Union in four major waves of deportation between 1939 and 1941.[Note 1]

Soviet forces occupied eastern Poland until the summer of 1941, when they were driven out by the German army in the course of Operation Barbarossa. The area was under German occupation until the Red Army reconquered it in the summer of 1944. An agreement at the Yalta Conference permitted the Soviet Union to annex almost all of their Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact portion of the Second Polish Republic, compensating the People's Republic of Poland with the southern half of East Prussia and territories east of the Oder–Neisse line.[139] The Soviet Union enclosed most of the conquered annexed territories into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.[139]

After the end of World War II in Europe, the USSR signed a new border agreement with the Soviet-backed and installed Polish communist puppet state on 16 August 1945. This agreement recognized the status quo as the new official border between the two countries with the exception of the region around Białystok and a minor part of Galicia east of the San river around Przemyśl, which were later returned to Poland.[140]

1945-1949: Hungary

As the allies were on their way to victory in World War II, Hungary was governed by the Hungarist Arrow Cross Party under the Government of National Unity. They were facing mostly advancing Soviet and Romanian forces. On February 13, 1945 the forces captured Budapest, by April 1945 German forces were driven out of the country.[141] They occupied the country and set it up as a Satellite State called the Second Hungarian Republic. In the 1945 Hungarian Parliamentary Election the Independent Smallholders Party won 57% of the vote while the communists won only 17%. In response the Soviet forces refused to allow the party to take power, and the communists took control of the government in a coup. Their rule saw the Stalinization of the country, and with the help of the USSR sent dissidents to Gulags in the Soviet Union, as well as setting up the Security Police known as the State Protection Authority (AVO).[142][143] In February 1947 the police began targeting member of the Independent Smallholders Party and the National Peasants Party. As well in 1947 the Hungarian government forced the leaders of non communist parties to cooperate with the government. The Social Democratic Party was taken over while the Secretary of Independent Smallholders Party was sent to Siberia. In June 1948 the Social Democrats were forced to fuse with the communists to form the Hungarian Working People's Party.[144] In the 1949 Hungarian parliamentary elections the voters were only presented with a list of communist candidates and the Hungarian government drafted a new constitution from the 1936 Soviet Constitution, and made themselves into the People's Republic of Hungary with Matyas Rakosi as the de facto leader.[145]

1945: Germany

The Soviet Union entered Warsaw on 17 January 1945, after the city was destroyed and abandoned by the Germans. Over three days, on a broad front incorporating four army fronts, the Red Army launched the Vistula–Oder Offensive across the Narew River and from Warsaw. The Soviets outnumbered the Germans on average by 5–6:1 in troops, 6:1 in artillery, 6:1 in tanks and 4:1 in self-propelled artillery. After four days, the Red Army broke out and started moving thirty to forty kilometres a day, taking the Baltic states: Danzig, East Prussia and Poznań, and drawing up on a line sixty kilometres east of Berlin along the River Oder. During the full course of the Vistula–Oder operation (23 days), the Red Army forces sustained 194,191 total casualties (killed, wounded and missing) and lost 1,267 tanks and assault guns.

A limited counter-attack (codenamed Operation Solstice) by the newly created Army Group Vistula, under the command of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, had failed by 24 February, and the Red Army drove on to Pomerania and cleared the right bank of the Oder River. In the south, the German attempts in to relieve the encircled garrison at Budapest (codenamed Operation Konrad) failed and the city fell on 13 February. On 6 March, the Germans launched what would be their final major offensive of the war, Operation Spring Awakening, which failed by 16 March. On 30 March, the Red Army entered Austria and captured Vienna on 13 April.

OKW claimed German losses of 77,000 killed, 334,000 wounded and 292,000 missing, for a total of 703,000 men, on the Eastern Front during January and February 1945.[146]

On 9 April 1945, Königsberg in East Prussia finally fell to the Red Army, although the shattered remnants of Army Group Centre continued to resist on the Vistula Spit and Hel Peninsula until the end of the war in Europe. The East Prussian operation, though often overshadowed by the Vistula–Oder operation and the later battle for Berlin, was in fact one of the largest and costliest operations fought by the Red Army throughout the war. During the period it lasted (13 January – 25 April), it cost the Red Army 584,788 casualties, and 3,525 tanks and assault guns.

The fall of Königsberg allowed Stavka to free up General Konstantin Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front (2BF) to move west to the east bank of the Oder. During the first two weeks of April, the Red Army performed their fastest front redeployment of the war. General Georgy Zhukov concentrated his 1st Belorussian Front (1BF), which had been deployed along the Oder river from Frankfurt in the south to the Baltic, into an area in front of the Seelow Heights. The 2BF moved into the positions being vacated by the 1BF north of the Seelow Heights. While this redeployment was in progress gaps were left in the lines and the remnants of the German 2nd Army, which had been bottled up in a pocket near Danzig, managed to escape across the Oder. To the south, General Ivan Konev shifted the main weight of the 1st Ukrainian Front (1UF) out of Upper Silesia north-west to the Neisse River.[147] The three Soviet fronts had altogether around 2.5 million men (including 78,556 soldiers of the 1st Polish Army): 6,250 tanks, 7,500 aircraft, 41,600 artillery pieces and mortars, 3,255 truck-mounted Katyusha rocket launchers, (nicknamed "Stalin Organs"), and 95,383 motor vehicles, many of which were manufactured in the USA.[147]

1945-1950: China

On 9 August 1945, the Soviet Union invaded the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. It was the last campaign of the Second World War, and the largest of the 1945 Soviet–Japanese War, which resumed hostilities between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Empire of Japan after almost six years of peace. Soviet gains on the continent were Manchukuo, Mengjiang (Inner Mongolia) and northern Korea. The Soviet entry into the war and the defeat of the Kwantung Army was a significant factor in the Japanese government's decision to surrender unconditionally, as it made apparent the Soviet Union had no intention of acting as a third party in negotiating an end to hostilities on conditional terms.[148][149][150][151][152][153][154][155]

At the same time tensions were starting to resurface between the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Kuomintang (KMT), known as the Communists and Nationalists respectively. The two groups had stopped fighting to form the Second United Front in order to fend off the Japanese Empire. During the Second Sino-Japanese War the CPC gained many members due to their success against the Japanese. The fighting even caused the United Front to be dissolved in 1941.[156] Through the war with the Japanese there were tensions and incidents of fighting, however the USSR and the USA made sure that they stayed at enough peace to stop the Japanese from winning the war.[157] In March 1946 the USSR would withdraw leaving most of Manchuria to the Communists. As well the USSR handed over most of the weapons to the CPC that they had captured from the Japanese.[158][159] Fighting commenced between the two groups and a war began that would last for three years.[160]

The Communists were able to start gaining ground and by 1948 they were pushing the Nationalists out and taking more and more of China. The USSR continued to give aid to the CPC and even helped them in taking Xinjiang from the Nationalists.[161] In October 1949 Mao Zedong, the leader of the communists, proclaimed the People's Republic of China effectively ending the civil war. In May 1950 the last of the KMT had been completely pushed off of mainland China and Chiang Kai-Shek, the leader of the Nationalists, retreated to Taiwan and formed the Republic of China.[162] Both mainland China and the USSR stayed good allies until the Sino-Soviet Split after Stalin's death.

1945–1953: Korea

The 1948 Korean elections were overseen primarily by the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea, or UNTCOK. The Soviet Union forbade the elections in the north of the peninsula,[163] while the United States planned to hold separate elections in the south of the peninsula, a plan which was opposed by Australia, Canada and Syria as members of the commission.[164] According to Gordenker, the commission acted:

in such a way as to affect the controlling political decisions regarding elections in Korea. Moreover, UNTCOK deliberately and directly took a hand in the conduct of the 1948 election.[165]

Faced with this, UNTCOK eventually recommended the election take place only in the south, but that the results would be binding on all of Korea.[163]

In June 1950, Kim Il-sung's North Korean People's Army invaded South Korea.[58] Fearing that communist Korea under a Kim Il-sung dictatorship could threaten Japan and foster other communist movements in Asia, Harry Truman, then President of the United States, committed U.S. forces and obtained help from the United Nations to counter the North Korean invasion. The Soviets boycotted UN Security Council meetings while protesting the Council's failure to seat the People's Republic of China and, thus, did not veto the Council's approval of UN action to oppose the North Korean invasion. A joint UN force of personnel from South Korea, the United States, Britain, Turkey, Canada, Australia, France, the Philippines, the Netherlands, Belgium, New Zealand and other countries joined to stop the invasion.[59] After a Chinese invasion to assist the North Koreans, fighting stabilized along the 38th parallel, which had separated the Koreas. The Korean Armistice Agreement was signed in July 1953 after the death of Stalin, who had been insisting that the North Koreans continue fighting.[60]

1948: Czechoslovakia

Following World War II, Czechoslovakia was under the influence of the USSR and, during the election of 1946, the communists would win 38% of the vote.[166] The communists had been alienating many citizens in Czechoslovakia due to the use of the police force and talks of collectivization of a number of industries.[167] Stalin was against democratic ways of taking power since the communist parties in Italy and France had failed to take power. In the winter of 1947, the communist party decided to stage a coup; the USSR would come to support them. The non-communists attempted to act before the communists took the police force completely, but the communists occupied the offices of non-communists.[168] The army, under the direction of Defence Minister Ludvík Svoboda, who was formally non-partisan but had facilitated communist infiltration into the officer corps, was confined to barracks and did not interfere.[169] The communists threatened a general strike too. Edvard Benes, fearing direct Soviet intervention and a civil war, surrendered and resigned.[170]

1948–1949: Yugoslavia

During World War II, the communist Yugoslav Partisans had been the main resistance to the Axis in Yugoslavia. As the axis were defeated the Partisans took power and Josef Bronz Tito became the head of Yugoslavia. This had been done without much Soviet help, so Tito was allowed to and did run his own path in defiance to Stalin. Economically, he implemented a different view to the USSR[171] and attempted to make Yugoslavia into a regional power by absorbing Bulgaria and Albania into Yugoslavia as well as funding the Greek Communists in the Greek Civil War, in order to absorb Greece too.[172] Stalin did not approve of this and expelled Yugoslavia from the East Bloc. There was military buildup and a planned invasion in 1949 that was never put through.[173] As well, since 1945, the USSR had a spy ring within Yugoslavia[174] and Stalin attempted to assassinate Tito several times. Stalin remarked "I will shake my little finger and there will be no more Tito".[175] However, these assassinations would fail, and Tito would write back to Stalin "Stop sending people to kill me. We've already captured five of them, one of them with a bomb and another with a rifle. [...] If you don't stop sending killers, I'll send one to Moscow, and I won't have to send a second."[176] Yugoslavia would go on to become one of the main founders and leaders the Non-Aligned Movement.[177]

1948: Italy

In the 1948 Italian elections, described as an "apocalyptic test of strength between communism and democracy,"[178] the Soviet Union funneled as much as $10 million monthly to the communists parties and leveraged its influence on Italian companies via contracts to support them,[179] while the Truman administration and the Roman Catholic Church funneled millions of dollars in funding to the Christian Democracy party and other parties through the War Powers Act of 1941 in addition to supplying military advisers, in preparation for a potential civil war.[178][180]:107–8 Christian Democrats eventually won with a majority.[180]:108–9

1953–1991: Rest of the Cold War

1956: Hungary

After Stalinist dictator Mátyás Rákosi was replaced by Imre Nagy following Stalin's death[44][not in citation given] and Polish reformist Władysław Gomułka was able to enact some reformist requests,[45] large numbers of protesting Hungarians compiled a list of Demands of Hungarian Revolutionaries of 1956,[46] including free secret-ballot elections, independent tribunals, and inquiries into Stalin and Rákosi Hungarian activities. Under the orders of Soviet defense minister Georgy Zhukov, Soviet tanks entered Budapest.[47]Protester attacks at the Parliament forced the collapse of the government.[48]

The new government that came to power during the revolution formally disbanded the Hungarian secret police, declared its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact and pledged to re-establish free elections. The Soviet Politburo thereafter moved to crush the revolution with a large Soviet force invading Budapest and other regions of the country.[49] Approximately 200,000 Hungarians fled Hungary,[50] some 26,000 Hungarians were put on trial by the new Soviet-installed János Kádár government and, of those, 13,000 were imprisoned.[51] Imre Nagy was executed, along with Pál Maléter and Miklós Gimes, after secret trials in June 1958. By January 1957, the Hungarian government had suppressed all public opposition. These Hungarian government's violent oppressive actions alienated many Western Marxists,[who?] yet strengthened communist control in all the European communist states, cultivating the perception that communism was both irreversible and monolithic.

1960: United States

Adlai Stevenson II had been the Democratic presidential nominee in 1952 and 1956, and the Soviets offered him propaganda support if he ran again for president in 1960, but Stevenson declined.[181] Instead, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev backed John F. Kennedy in a very close election against Richard Nixon, with whom Khrushchev had clashed in the 1959 Kitchen Debate.[182] On July 1, 1960, a Soviet MiG-19 shot down an American RB-47H reconnaissance aircraft in the international airspace over the Barents Sea with four of the crew being killed and two captured by the Soviets: John R. McKone and Freeman B. Olmstead.[183] The Soviets held on to the two prisoners, in order to avoid giving Nixon (who was the incumbent Vice-President of the United States) an opportunity to boast about his ability to work with the Soviets, and the two Air Force officers were released days after Kennedy's inauguration, on January 25, 1961. Khrushchev later bragged that Kennedy acknowledged the Soviet help: "You're right. I admit you played a role in the election and cast your vote for me...."[182] Former Soviet ambassador to the United States Oleg Troyanovsky confirmed Kennedy's acknowledgment, but also quoted Kennedy doubting whether the Soviet support made a difference: "I don't think it affected the elections in any way."[182][184]

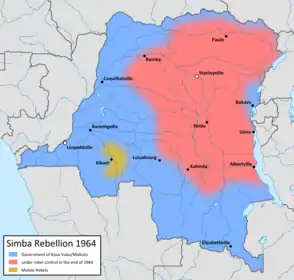

1961–1965: Congo-Leopoldville

In 1960, Belgium, the United States, and other countries covertly overthrew Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in a coup lead by Mobutu Sese Seko. Afterwards, Seko began getting support from the US. Many politicians who had been allied to Lumumba were forced out of government. Many of Lumumba allied politicians began to foment discontent and dissent. They formed a new government in Stanleyville in the East of the country called the Free Republic of Congo with the support of the Soviet Union. The supporters of Lumumba eventually agreed to join back however they felt cheated on after and turned again against Mobutu in a more violent form of resistance. Maoist Pierre Mulele began the Kwilu Rebellion, soon after Christopher Gbenye and Gaston Soumialot led the APL (Armée Populaire de Libération), also known as the Simbas, in the Eastern Congo in the Simba Rebellion.[185]

Mobutu was already receiving assistance from the United States, and the Simbas began to receive funding from the USSR along with other countries also aligned with them. The Soviet Union implored neighboring nationalistic governments to aid the rebels. The Soviet leadership promised that it would replace all weaponry given to the Simbas but rarely did so.[186] In order to supply the rebels, the Soviet Union transported equipment by cargo planes to Juba in allied Sudan. From there, the Sudanese brought the weapons to Congo.[187] This operation backfired, however, as southern Sudan was invaded in the First Sudanese Civil War. The Sudanese Anyanya insurgents consequently ambushed the Soviet-Sudanese supply convoies, and took the weapons for themselves.[188][187] When the CIA learned of these attacks, it allied with the Anyanya. The Anyanya helped the Western and Congolese air forces locate and destroy Simba rebel camps and supply routes.[189] In return, the Sudanese rebels were given weapons for their own war.[190] Angered by the Soviet support for the insurgents, the Congolese government expelled the Soviet embassy's personnel from the country in July 1964. The Soviet leadership responded by increasing its aid for the Simbas.[186] As well in 1965 Che Guevara went and fought alongside future leader of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Laurent-Desire Kabila.[191]

However the rebellion would begin to collapse for a variety of reasons including bad coordination and relations with the USSR, the Sino-Soviet Split, support for Mobutu by the U.S. and Belgium, counter insurgent tactics, and many other reasons.[192][193][194] While it would be crushed the Simbas still held parts of the Eastern Congo and resisted the government until 1996 during the First Congo War.[195]

1964: Chile

Between 1960 and 1969, the Soviet government funded the Communist Party of Chile at a rate of between $50,000 and $400,000 annually. In the 1964 Chilean elections, the U.S. government supplied $2.6 million in funding for candidate Eduardo Frei Montalva, whose opponent, Salvador Allende was a prominent Marxist, as well as additional funding with the intention of harming Allende's reputation.[196]:38–9 As Gustafson phrased the situation:

It was clear the Soviet Union was operating in Chile to ensure Marxist success, and from the contemporary American point of view, the United States was required to thwart this enemy influence: Soviet money and influence were clearly going into Chile to undermine its democracy, so U.S. funding would have to go into Chile to frustrate that pernicious influence.

1965–1979: Rhodesia

By the end of the nineteenth Century, the British Empire had control of much of Southern Africa. This included the three colonies of Northern Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia, named for Cecil Rhodes, and Nyasaland, which formed the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Northern Rhodesia would go on to become independent as Zambia and Nyasaland would become Malawi.[197] A white minority had ruled Southern Rhodesia since World War II. However, the British had made a policy of majority rule as a condition of independence, and Southern Rhodesia's white minority still wanted to maintain power.[198][199][200] On November 11, 1965, Southern Rhodesia declared independence and formed Rhodesia.[201][202][203]

In Rhodesia, the white minority still held political power and held most of the country's wealth, while being led by Ian Smith. Rhodesia would gain very little recognition across the world, though it would have some covert support. Two main armed groups rose up in order to overthrow the white minority in 1964, a year before Rhodesia's declaration of independence. Both were Marxist organizations that got support from different sides of the Sino-Soviet Split. One was ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union), who organized rural areas, and thus got support from China. The other was ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People's Union), who organized primarily urban areas, thus getting support from the USSR. ZIPRA (Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army), the armed wing of ZAPU, took advice from its Soviet instructors in formulating its vision and strategy of popular revolution. About 1,400 Soviets, 700 East German and 500 Cuban instructors were deployed to the area.[204] While both groups fought against the Rhodesian government, they would also sometimes fight each other. The fighting began a year before Rhodesian independence.

Rhodesia was not able to survive the war as into the 1970s guerilla activity began to intensify.[205][206] Eventually, a compromise was reached in 1978 where the country was renamed Zimbabwe-Rhodesia. This was still seen as not enough and the war would continue.[207] Then, after a brief British recolonization, Zimbabwe was created, with ZANU leader Robert Mugabe elected as president.[208] In the 1980 election, ZAPU would not win a majority; they would later fuse with ZANU in 1987 into ZANU-PF. They are now split.[209][210]

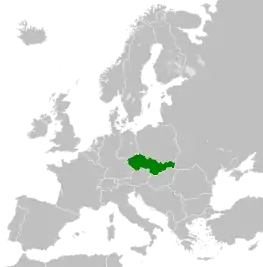

1968: Czechoslovakia

A period of political liberalization took place in 1968 in Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring. The event was spurred by several events, including economic reforms that addressed an early 1960s economic downturn.[211][212] In April, Czechoslovakian leader Alexander Dubček launched an "Action Program" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of movement, along with an economic emphasis on consumer goods, the possibility of a multiparty government and limiting the power of the secret police.[213][214] Initial reaction within the Eastern Bloc was mixed, with Hungary's János Kádár expressing support, while Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and others grew concerned about Dubček's reforms, which they feared might weaken the Eastern Bloc's position during the Cold War.[215][216] On August 3, representatives from the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia met in Bratislava and signed the Bratislava Declaration, which declaration affirmed unshakable fidelity to Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism and declared an implacable struggle against "bourgeois" ideology and all "anti-socialist" forces.[217]

On the night of August 20–21, 1968, Eastern Bloc armies from four Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary – invaded Czechoslovakia.[218][219] The invasion comported with the Brezhnev Doctrine, a policy of compelling Eastern Bloc states to subordinate national interests to those of the Bloc as a whole and the exercise of a Soviet right to intervene if an Eastern Bloc country appeared to shift towards capitalism.[220][221] The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, including an estimated 70,000 Czechs initially fleeing, with the total eventually reaching 300,000.[222] In April 1969, Dubček was replaced as first secretary by Gustáv Husák, and a period of "normalization" began.[223] Husák reversed Dubček's reforms, purged the party of liberal members, dismissed opponents from public office, reinstated the power of the police authorities, sought to re-centralize the economy and re-instated the disallowance of political commentary in mainstream media and by persons not considered to have "full political trust".[224][225] The international image of the Soviet Union suffered considerably, especially among Western student movements inspired by the "New Left" and non-Aligned Movement states. Mao Zedong's People's Republic of China, for example, condemned both the Soviets and the Americans as imperialists.

1974-1990: Ethiopia

Emperor Haile Selassie I of the Ethiopian Empire was continuing to hold onto power in the country and to protect the feudal system that held the country together. The empire had lasted thousands of years and into the 1950s and 1960s it was starting to become more unstable. The people in the country had suffered through famines that the government had been unable or refused to alleviate such as the 1958 Famine of Tigray and especially the Wollo Famine from 1972 to 1974.[226][227] The emperor set up the Derg to investigate how rations were handed out, but were given more power and supported munitys among the soldiers. They eventually turned against the emperor. They led the overthrow of the emperor on September 12, 1974 in the Ethiopian revolution.[228] The Derg soon after abolished the monarchy and ended the empire. The leader of the Derg was Mengistu Haile Mariam. He became a Marxist-Leninist and the Derg came to rule Ethiopia as a Marxist-Leninist military Junta.[229] The Soviet Union supported him and the Derg, and they began to supply him weapons and portray him positively. He than tried to model Ethiopia off of the Eastern European members of the Warsaw Pact.[230]

As this occurred many other leftist, separatist, and anti communist groups rose up, beginning the Ethiopian Civil War. Among the groups was the conservative Ethiopion Democratic Union (EDU). They represented landowners who were opposed to the Nationalization policies of the Derg, monarchists, and high-ranking military officers who were forced out by mutineers of the Derg. As well there were a number of dissenting Marxist-Leninist groups opposed the Derg for ideological reasons. These were the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP), Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), Ethiopian People's Democratic Movement (EPDM), and All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement (MEISON). The Derg had to contend with all of these along with many separatist organizations and an invasion by Somalia. The Soviet Union supported the Derg government.[231][232][233] The Derg with that support instigated the Qey Shibir (Ethiopian Red Terror), targeted especially against the EPRP and MEISON.[234] Thousands were killed by the Qey Shibir, as well as forced deportations.[235][236] As well the brutal 1983-1985 famine hit the country, which was vastly extended by government policies.[237]

In 1987 the Derg formed the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE), and continued suppressing rebel groups, and Mariam attempted to transition to a socialist republic. In 1989 the TPLF and EPDM fused into the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), and it along with Eritrean separatists began to gain ground and victories.[238] In 1990 as the Eastern Bloc began to collapse the USSR stopped any aid and supplies to Ethiopia. A year later Mengistu Haile Mariam fled the country, as the PDRE fell to the rebels.[239]

1978–79: Iran

.svg.png.webp)

1978-1989: Cambodia

In the years after the Vietnam War the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the Democratic Kampuchea had been trying to build relations between one another. The Democratic Kampuchea was the government of Cambodia under the rule of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. While both countries tried to maintain good relations they both were still suspicious of each other and fought in occasional border skirmishes. In 1977 relations fully deteriorated, and in 1978 this would all come to a head. On December 25, 1978 Vietnam invaded the country in order to remove the Khmer Rouge from power. Their invasion was supported by the Soviet Union who ended up sending them $1.4 billion in military aid for their invasion, and between 1981-1985 peaked at $1.7 billion.[240] As well the Soviet Union provided Vietnam with a total of $5.4 billion in order to alleviate sanctions and help with their third five-year plan (1981-1985). The Soviet Union also provided 90% of Vietnam's demand for raw materials and 70% of its grain imports.[240] Along with that the Soviet Union vetod many resolutions at the United Nations that were critical of the invasion or attempted to put sanctions on it.[241] Even though the figures suggest the Soviet Union was a reliable ally, privately Soviet leaders were dissatisfied with Hanoi's handling of the stalemate in Kampuchea and resented the burden of their aid program to Vietnam as their own country was undergoing economic reforms. In 1986, the Soviet Government announced that it would reduce aid to friendly nations; for Vietnam, those reductions meant the loss of 20% of its economic aid and one-third of its military aid.[242] After the invasion Vietnam attempted to build a new government in the country and fight a guerilla war against the Khmer Rouge. To implement the new reforms in the country, Vietnam, with support from the Soviet Union, started transferring several years' worth of military equipment to the KPRAF, which numbered more than 70,000 soldiers. The Vietnamese Ministry of Defense's International Relations Department then advised its Kampuchean counterparts to only use the available equipment to maintain their current level of operations, and not to engage in major operations which could exhaust those supplies.[243] By the end of the war the Soviet Union started to decline, but despite this the regime change ended successfully, though the Khmer Rouge would be active in guerrilla actions for many more years.

1979–1989: Afghanistan

During the 1978 coup d'état in Afghanistan, where the communist party took power, it initiated a series of radical modernization reforms throughout the country that were forced and deeply unpopular, particularly among the more traditional rural population and the established traditional power structures.[37] The regime's nature[38] of vigorously suppressing opposition, including executing thousands of political prisoners, led to the rise of anti-government armed groups and, by April 1979, large parts of the country were in open rebellion.[39] The ruling party itself experienced deep rivalries and, in September 1979, the President, Nur Mohammad Taraki, was murdered under orders of the second-in-command, Hafizullah Amin, which soured relations with the Soviet Union. Eventually the Soviet government, under leader Leonid Brezhnev, decided to deploy the 40th Army on December 24, 1979.[40] Arriving in the capital Kabul, they staged a coup,[41] killing president Amin and installing Soviet loyalist Babrak Karmal from a rival faction.[39] The deployment had been variously called an "invasion" (by Western media and the rebels) or a legitimate supporting intervention (by the Soviet Union and the Afghan government)[42][43] on the basis of the Brezhnev Doctrine.

In January 1980, foreign ministers from 34 nations of the Islamic Conference adopted a resolution demanding "the immediate, urgent and unconditional withdrawal of Soviet troops" from Afghanistan.[44] The UN General Assembly passed a resolution protesting the Soviet intervention by a vote of 104 (for) to 18 (against), with 18 abstentions and 12 members of the 152-nation Assembly absent or not participating in the vote;[44][45] only Soviet allies Angola, East Germany and Vietnam, along with India, supported the intervention.[46] Afghan insurgents began to receive massive amounts of aid and military training in neighboring Pakistan and China,[15] paid for primarily by the United States and Arab monarchies in the Persian Gulf.[7][8][15][11][47][48][49][50] As documented by the National Security Archive, "the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) played a significant role in asserting U.S. influence in Afghanistan by funding military operations designed to frustrate the Soviet invasion of that country. CIA covert action worked through Pakistani intelligence services to reach Afghan rebel groups."[51] Soviet troops occupied the cities and main arteries of communication, while the mujahideen waged guerrilla war in small groups operating in the almost 80 percent of the country that was outside government and Soviet control, almost exclusively being the rural countryside.[52] The Soviets used their air power to deal harshly with both rebels and civilians, levelling villages to deny safe haven to the mujahideen, destroying vital irrigation ditches, and laying millions of land mines.[53][54][55][56]

The international community imposed numerous sanctions and embargoes against the Soviet Union, and the U.S. led a boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow. The boycott and sanctions exacerbated Cold War tensions and enraged the Soviet government, which later led a revenge boycott of the 1984 Olympics held in Los Angeles.[57] The Soviets initially planned to secure towns and roads, stabilize the government under new leader Karmal, and withdraw within six months or a year. But they were met with fierce resistance from the guerillas,[58] and were stuck in a bloody war that lasted nine years.[59] By the mid-1980s, the Soviet contingent was increased to 108,800 and fighting increased, but the military and diplomatic cost of the war to the USSR was high.[9] By mid-1987, the Soviet Union, now under reformist leader Mikhail Gorbachev, announced it would start withdrawing its forces after meetings with the Afghan government.[5][6] The final troop withdrawals started on May 15, 1988, and ended on February 15, 1989, leaving the government forces alone in the battle against the insurgents, which continued until 1992 when the former Soviet-backed government collapsed. Due to its length, it has sometimes been referred to as the "Soviet Union's Vietnam War" or the "Bear Trap" by the Western media.[60][61][62] The Soviets' failure in the war[63] is thought to be a contributing factor to the fall of the Soviet Union.[64]

1982–1990: Nicaragua

The US had been heavily involved in Nicaragua all throughout the 20th century. After the second occupation of Nicaragua the US friendly Somoza family was left in charge. Under their rule inequality and political repression became rampant. In 1961 the FSLN (Sandinista National Liberation Front), commonly known as the Sandinistas, was founded by radical students to oppose their rule. Throughout the 1960s they would build up their political base and organization. In the 1970s they began resistance against the government and the Somoza regime recognized them as a threat. In January 1978 anti-Somoza journalist Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal was killed, likely by Somoza allies. As a result, riots broke out across the country. The FSLN also called for a general strike which would be extremely successful at shutting down most of the countries businesses. On August 22, 1978 the FSLN did a massive series of kidnapping and attacks against the Somoza government. In early 1979 the OAS (Organization of American States) mediated negotiations between both groups, but the Sandinistas stopped them when they realized the Somoza regime had no intention of initiating free elections. In June 1979 the Saninistas held power over most of the country except the capital, and in July 1979 Anastasio Somoza Debayle resigned and his successor handed the capital to the FSLN.[244][245]

During the initial overthrow the Sandinistas already were receiving support from left wing and left leaning governments. The USSR immediately developed relations with the new government, and the two became good allies. The USSR would begin to send aid and military weapons to the government. During the 1980s, the Soviet Union provided full political, economic, military, and diplomatic support to the left wing government of Nicaragua. They provided free credit, economic subsidies and heavy weapon grants to the Sandinistas. The Nicaraguans got at no cost armaments such as heavily armed MI-24 attack helicopters (Hinds), and Mi-17 transport helicopters. Already former parts of the Somoza regime had begun to regroup and organize along the Nicaraguan border, forming the Contras. In the US the Carter Administration had tried to work with the new FSLN government, but the succeeding Reagan Administration had a much more anti communist foreign policy and began to give assistance to the Contras. The Contras launched an offensive against the FSLN government in 1981. The USSR responded by ramping up their military support in 1982. They would continue to give support against the Contras until the 1990 Nicaraguan General Election and the Contras ceasing of their hostilities.[246][247][248]

Notes

References

- Levin, Dov H. (June 2016). "When the Great Power Gets a Vote: The Effects of Great Power Electoral Interventions on Election Results". International Studies Quarterly. 60 (2): 189–202. doi:10.1093/isq/sqv016.

For example, the U.S. and the USSR/Russia have intervened in one of every nine competitive national level executive elections between 1946 and 2000.

- Levin, Dov H. (June 2016). "When the Great Power Gets a Vote: The Effects of Great Power Electoral Interventions on Election Results". International Studies Quarterly. 60 (2): 189–202. doi:10.1093/isq/sqv016.

- Levin, Dov H. (7 September 2016). "Sure, the U.S. and Russia often meddle in foreign elections. Does it matter?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Mansell, Wade and Openshaw, Karen, "International Law: A Critical Introduction," Chapter 5, Hart Publishing, 2014, https://books.google.com/booksid=XYrqAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT140

- "All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state." United Nations, "Charter of the United Nations," Article 2(4), http://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/chapter-i/index.html Archived October 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Fox, Gregory, "Regime Change," 2013, Oxford Public International Law, Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, Sections C(12) and G(53)–(55), Archived November 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Upton 1980, pp. 163–194, Alapuro 1988, pp. 158–162, 195–196, Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 35, 37, 39, 40, 50, 52, Haapala 1995, pp. 229–245, Klinge 1997, pp. 487–524, Kalela 2008b, pp. 31–44, Kalela 2008c, pp. 95–109, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50, Siltala 2014, pp. 51–89

- Keränen et al. 1992, p. 50, Haapala 1995, pp. 229–245, Klinge 1997, pp. 502–524, Kalela 2008b, pp. 31–44, Kalela 2008c, pp. 95–109, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50, Jyränki 2014, pp. 18–38

- Upton 1980, pp. 163–194, Kettunen 1986, pp. 9–89, Alapuro 1988, pp. 158–162, 195–196, Alapuro 1992, pp. 251–267, Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 35, 37, 39, 40, 50, 52, Haapala 1995, pp. 229–245, Klinge 1997, pp. 502–524, Haapala 2008, pp. 255–261, Kalela 2008b, pp. 31–44, Kalela 2008c, pp. 95–109, Siltala 2014, pp. 51–89

- The Bolsheviks received 15 million marks from Berlin after the October Revolution, but Lenin's authority was weak and Russia became embroiled in a civil war which turned the focus of all the major Russian military, political and economic activities inwards. Keränen et al. 1992, p. 36, Pipes 1996, pp. 113–149, Lackman 2000, pp. 86–95, Lackman 2009, pp. 48–57, McMeekin 2017, pp. 125–136

- Svinhufvud's initial vision was that the Senate would lead Finland and the independence process with a call for a Regent; there would be no talks with the Bolsheviks, who it was believed would not set a non-socialist Finland free. The vision of the socialists was that Parliament should lead Finland and that independence would be achieved more easily through negotiations with a weak Bolshevik government than with other parties of the Russian Constituent Assembly, Upton 1980, pp. 343–382, Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 73, 78, Manninen 1993c, Jutikkala 1995, pp. 11–20, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50, Jyränki 2014, pp. 18–38

- The Bolshevist Council of People's Commissars ratified the recognition on 4 January 1918. Upton 1980, pp. 343–382, Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 79, 81, Keskisarja 2017, pp. 13–74

- Upton 1980, pp. 390–515, Lappalainen 1981a, pp. 15–65, 177–182, Manninen* 1993c, pp. 398–432, Hoppu 2009a, pp. 92–111, Siltala 2014, pp. 51–89, Tikka 2014, pp. 90–118

- Upton 1980, pp. 390–515, Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 80–89, Manninen 1993b, pp. 96–177, Manninen* 1993c, pp. 398–432, Westerlund 2004b, pp. 175–188, Tikka 2014, pp. 90–118

- The Reds won the battle and gained 20,000 rifles, 30 machine guns, 10 cannons and 2 armoured vehicles. In total, the Russians delivered 20,000 rifles from the Helsinki and Tampere depots to the Reds. The Whites captured 14,500 rifles, 90 machine guns, 40 cannons and 4 mortars from the Russian garrisons. Some Russian army officers sold their unit's weapons both to the Reds and the Whites. Upton 1980, pp. 390–515, Lappalainen 1981a, pp. 15–65, 177–182, Klemettilä 1989, pp. 163–203, Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 80–89, Manninen 1993b, pp. 96–177, Manninen* 1993c, pp. 398–432, Tikka 2014, pp. 90–118

- Attempts at sustaining peace and neutrality between socialist and non-socialists were made in January 1918 by agreements at a local level, e.g. in Muurame, Savonlinna and Teuva, Kallioinen 2009, pp. 1–146

- The fall of the Russian Empire, the October revolt and Finnish Germanism had placed Gustaf Mannerheim in a controversial position. He opposed the Finnish and Russian Reds, as well as Germany, through alliance with Russian White officers who, in turn, did not support independence of Finland. Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 102, 142, Manninen 1995, pp. 21–32, Klinge 1997, pp. 516–524, Lackman 2000, Westerlund 2004b, pp. 175–188, Meinander 2012, pp. 7–47, Roselius 2014, pp. 119–155

- After the Russian Civil War, a gradually resurgent Russia recaptured many of the nations that had become independent in 1918. Upton 1981, pp. 255–278, Klemettilä 1989, pp. 163–203, Keränen et al. 1992, pp. 94, 106, Pietiäinen 1992, pp. 252–403, Manninen 1993c, Manninen 1995, pp. 21–32, Jussila 2007, pp. 276–282

- Upton 1981, pp. 262–265, Pietiäinen 1992, pp. 252–403, Manninen 1995, pp. 21–32

- (in Russian) Kuzmin, S. L., Oyuunchimeg, J. and Bayar, B. The battle at Ulaankhad, one of the main events in the fight for independence of Mongolia Archived 21 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Studia Historica Instituti Historiae Academiae Scientiarum Mongoli, 2011–12, vol. 41–42, no 14, pp. 182–217

- (in Russian) Kuzmin, S.L., Oyuunchimeg, J. and Bayar, B. The Ulaan Khad: reconstruction of a forgotten battle for independence of Mongolia Archived 21 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Rossiya i Mongoliya: Novyi Vzglyad na Istoriyu (Diplomatiya, Ekonomika, Kultura), 2015, vol. 4. Irkutsk, pp. 103–14.

- Докумэнты внэшнэй политики СССР [Foreign political events involving the Soviet Union], (Moscow, 1957), v. 3, no. 192, pp. 55-56.

- Cahoon, Ben. "Tannu Tuva". worldstatesmen.org.

- Jonathan D. Smele: Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916–1926, 2015, Lanham (Maryland) 2015, p. 1197.

- Frank Stocker: Als Vampire die Mark eroberten: Eine faszinierende Reise durch die rätselhafte Welt der Banknoten in 80 kurzen Geschichten, (online) 2015, p. 69.

- Indjin Bayart: An Russland, das kein Russland ist, Hamburg 2014, p. 114.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 281. ISBN 052-147-771-9.

- Li, Narangoa; Cribb, Robert (2014-09-02). Historical Atlas of Northeast Asia, 1590-2010: Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, Eastern Siberia. 2014. p. 175. ISBN 978-023-153-716-2.

- Sinor, Denis, ed. (1990). Aspects of Altaic Civilization III. London: Psychology Press. p. 8. ISBN 070-070-380-2.

- Lando, Steve (2010). Europas tungomål II (in Swedish). Sweden. p. 710. ISBN 978-917-465-076-1.

- Sidebotham, Herbert (16 August 1919). "The Third Afghan War". New Statesman.

- H. L (1932). "Soviet Treaties of Neutrality and Non-Aggression, 1931-32". Bulletin of International News. 8 (20): 3–6. JSTOR 25639033.

- Ritter, William S (1990). "Revolt in the Mountains: Fuzail Maksum and the Occupation of Garm, Spring 1929". Journal of Contemporary History 25: 547. doi:10.1177/002200949002500408.

- Ritter, William (1990). "Revolt in the Mountains: Fuzail Maksum and the Occupation of Garm, Spring 1929". Journal of Contemporary History. 25 (4): 547–580. doi:10.1177/002200949002500408. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 260761. S2CID 159486304.

- "Lessons for Leaders: What Afghanistan Taught Russian and Soviet Strategists | Russia Matters". www.russiamatters.org. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

In 1929 Stalin sent 1,000 Red Army soldiers into Afghanistan disguised as Afghan soldiers to operate jointly with some of Khan’s loyalists, according to Lyakhovsky’s book and a 1999 article in Rodina by Pavel Aptekar. The joint Soviet-Afghan unit took Mazar-i-Sharif in April 1929, but Stalin then had to recall his troops after learning that Khan had fled to India.

- Muhammad, Fayz; Hazārah, Fayz̤ Muḥammad Kātib (1999). Kabul Under Siege: Fayz Muhammad's Account of the 1929 Uprising. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 274. ISBN 9781558761551.

- Preston (2006). pp. 82–83.

- Preston (2006). p. 102.

- Howson (1998). pp. 1–2.

- Beevor (2006). pp. 30–33.

- Howson (1998). p. 125.

- Howson (1998). pp. 126–129.

- Howson (1998). p. 134.

- Payne (2004). pp. 156–157.

- Beevor (2006). pp. 152–153.

- Beevor (2006). p. 163.

- Graham (2005). p. 92.

- Thomas (2003). p. 944.

- Thomas (1961). p. 637.

- Beevor (2006). pp. 153–154.

- Richardson (2015). pp. 31–40

- Beevor (2006). pp. 273, 246.

- Beevor (2006). pp. 396–397.

- Derby (2009). p. 28.

- Taagepera, Rein (1993). Estonia: return to independence. Westview Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8133-1199-9.

- Ziemele, Ineta (2003). "State Continuity, Succession and Responsibility: Reparations to the Baltic States and their Peoples?". Baltic Yearbook of International Law. Martinus Nijhoff. 3: 165–190. doi:10.1163/221158903x00072.

- Kaplan, Robert B.; Jr, Richard B. Baldauf (2008-01-01). Language Planning and Policy in Europe: The Baltic States, Ireland and Italy. Multilingual Matters. p. 79. ISBN 9781847690289.

Most Western countries had not recognised the incorporation of the Baltic States into the Soviet Union, a stance that irritated the Soviets without ever becoming a major point of conflict.

- Kavass, Igor I. (1972). Baltic States. W. S. Hein.

The forcible military occupation and subsequent annexation of the Baltic States by the Soviet Union remains to this day (written in 1972) one of the serious unsolved issues of international law

- Davies, Norman (2001). Dear, Ian (ed.). The Oxford companion to World War II. Michael Richard Daniell Foot. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- Mälksoo (2003), p. 193.

- The Occupation of Latvia Archived 2007-11-23 at the Wayback Machine at Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia

- "22 September 1944 from one occupation to another". Estonian Embassy in Washington. 2008-09-22. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

For Estonia, World War II did not end, de facto, until 31 August 1994, with the final withdrawal of former Soviet troops from Estonian soil.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand; Gerard Pieter van den Berg; William B. Simons (1985). Encyclopedia of Soviet law. BRILL. p. 461. ISBN 90-247-3075-9.

On March 26, 1949, the US Department of State issued a circular letter stating that the Baltic countries were still independent nations with their own diplomatic representatives and consuls.

- Fried, Daniel (June 14, 2007). "U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2012. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

From Sumner Wells' declaration of July 23, 1940, that we would not recognize the occupation. We housed the exiled Baltic diplomatic delegations. We accredited their diplomats. We flew their flags in the State Department's Hall of Flags. We never recognized in deed or word or symbol the illegal occupation of their lands.

- Lauterpacht, E.; C. J. Greenwood (1967). International Law Reports. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-521-46380-7.

The Court said: (256 N.Y.S.2d 196) "The Government of the United States has never recognized the forceful occupation of Estonia and Latvia by the Soviet Union of Socialist Republics nor does it recognize the absorption and incorporation of Latvia and Estonia into the Union of Soviet Socialist republics. The legality of the acts, laws and decrees of the puppet regimes set up in those countries by the USSR is not recognized by the United States, diplomatic or consular officers are not maintained in either Estonia or Latvia and full recognition is given to the Legations of Estonia and Latvia established and maintained here by the Governments in exile of those countries

- Motion for a resolution on the Situation in Estonia by the European Parliament, B6-0215/2007, 21.5.2007; passed 24.5.2007. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- Dehousse, Renaud (1993). "The International Practice of the European Communities: Current Survey". European Journal of International Law. 4 (1): 141. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejil.a035821. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-12-09.