Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC; Arabic: منظمة التعاون الإسلامي, romanized: Munaẓẓama at-Taʿāwun al-ʾIslāmiyy; French: Organisation de la coopération islamique), formerly the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, is an international organization founded in 1969, consisting of 57 member states, with a collective population of over 1.8 billion as of 2015 with 49 countries being Muslim-majority countries.[1] The organisation states that it is "the collective voice of the Muslim world" and works to "safeguard and protect the interests of the Muslim world in the spirit of promoting international peace and harmony".[2]

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation | |

|---|---|

| |

Motto: "To safeguard the interests and ensure the progress and well-being of Muslims" | |

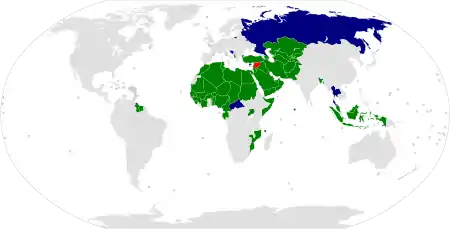

Member states Observer states Suspended states | |

| Administrative centre (Headquarters) | |

| Official languages | |

| Type | Religious |

| Membership | 57 member states |

| Leaders | |

• Secretary-General | Yousef Al-Othaimeen |

| Establishment | |

• Charter signed | 25 September 1969 |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 1.81 billion |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $27.949 trillion |

• Per capita | $19,451 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $9.904 trillion |

• Per capita | $9,361 |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 122nd |

Website www.oic-oci.org | |

| Organisation of Islamic Cooperation |

|---|

| Economy |

| Education |

| Member states |

| Parliamentary Union |

The OIC has permanent delegations to the United Nations and the European Union. The official languages of the OIC are Arabic, English, and French.

History

Al-Aqsa fire

On 21 August 1969 a fire was started in the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. Amin al-Husseini, the former Mufti of Jerusalem, called the arson a "Jewish crime" and called for all Muslim heads of state to convene a summit.[3] The fire, which "destroyed part of the old wooden roof and a 800-year-old pulpit"[4] was blamed on the mental illness of the perpetrator – Australian Christian fundamentalist Denis Michael Rohan — by Israel, and on Zionists and Zionism in general by the Islamic conference.[5]

Islamic Conference

On 25 September 1969, an Islamic Conference, a summit of representatives of 24 Muslim majority countries (most of the representatives being heads of state), was held in Rabat, Morocco.[3][2] A resolution was passed stating that

"Muslim government would consult with a view to promoting among themselves close cooperation and mutual assistance in the economic, scientific, cultural and spiritual fields, inspired by the immortal teachings of Islam."[3]

Six months later in March 1970, the First Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers was held in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.[5] In 1972, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC, now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) was founded.[6]

While the al-Aqsa fire is regarded as one of the catalysts for the formation of the OIC, many Muslims have aspired to a pan-Islamic institution that would serve the common political, economic, and social interests of the ummah (Muslim community) since the 19th century. In particular, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the Caliphate after World War I left a vacuum.

Goals

According to its charter, the OIC aims to preserve Islamic social and economic values; promote solidarity amongst member states; increase cooperation in social, economic, cultural, scientific, and political areas; uphold international peace and security; and advance education, particularly in the fields of science and technology.[2]

The emblem of the OIC contains three main elements that reflect its vision and mission as incorporated in its new Charter. These elements are: the Kaaba, the Globe, and the Crescent.

On 5 August 1990, 45 foreign ministers of the OIC adopted the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam to serve as a guidance for the member states in the matters of human rights in as much as they are compatible with the Sharia, or Quranic Law.[7]

In March 2008, the OIC conducted a formal revision of its charter. The revised charter set out to promote human rights, fundamental freedoms, and good governance in all member states. The revisions also removed any mention of the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. Within the revised charter, the OIC has chosen to support the Charter of the United Nations and international law, without mentioning the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[8]

Refugees

According to the UNHCR, OIC countries hosted 18 million refugees by the end of 2010. Since then OIC members have absorbed refugees from other conflicts, including the uprising in Syria. In May 2012, the OIC addressed these concerns at the "Refugees in the Muslim World" conference in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.[9]

New name and emblem

On 28 June 2011 during the 38th Council of Foreign Ministers meeting (CFM) in Astana, Kazakhstan, the organisation changed its name from Organisation of the Islamic Conference (Arabic: منظمة المؤتمر الإسلامي; French: Organisation de la Conférence Islamique) to its current name.[10] The OIC also changed its logo at this time.

Member states

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation has 57 members, 56 of which are also member states of the United Nations, the exception being Palestine. Some members, especially in West Africa and South America, are – though with large Muslim populations – not necessarily Muslim majority countries. A few countries with significant Muslim populations, such as Russia and Thailand, sit as Observer States.

The collective population of OIC member states is over 1.9 billion as of 2018.

Africa

Asia

Europe

Positions

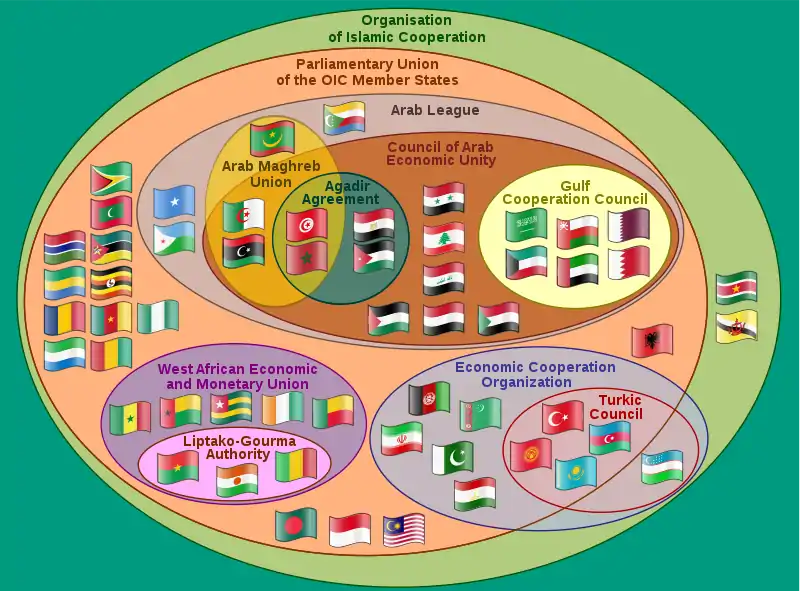

The Parliamentary Union of the OIC Member States (PUOICM) was established in Iran in 1999, and its head office is situated in Tehran. Only OIC members are entitled to membership in the union.[12]

On 27 June 2007, then-United States President George W. Bush announced that the United States would establish an envoy to the OIC. Bush said of the envoy, "Our special envoy will listen to and learn from representatives from Muslim states, and will share with them America's views and values."[13] As of June 2015, Arsalan Suleman is acting special envoy. He was appointed on 13 February 2015.[14] In an investigation of the accuracy of a series of chain emails, Snopes.com reported that during the October 2003 – April 2004 session of the General Assembly, 17 individual members of the OIC voted against the United States 88% of the time.[15]

The OIC, on 28 March 2008, joined the criticism of the film Fitna by Dutch lawmaker Geert Wilders, which features disturbing images of violent acts juxtaposed with alleged verses from the Quran.[16]

In March 2015, the OIC announced its support for the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis.[17]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The OIC supports a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

The OIC has called for boycott of Israeli products in effort to pressure Israel into ending the occupation of the Palestinian territories.[18][19]

There was a meeting in Conakry in 2013. Secretary-General Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu said that foreign ministers would discuss the possibility of cutting ties with any state that recognised Jerusalem as the capital of Israel or that moves its embassy to its environs.[20]

In December 2017, the extraordinary meeting held to response Donald Trump's decision on recognizing Jerusalem, resulting "Istanbul Declaration on Freedom for Al Quds."[21]

In September 2019, the OIC condemned Benjamin Netanyahu's plans to annex the eastern portion of the occupied West Bank known as the Jordan Valley.[22]

Relationship with India

Islam is the second-largest religion in India after Hinduism, with roughly 15% of the country's population or 201 million people identifying as adherents of Islam (2018 estimate).[23][24][25] It makes India the country with the largest Muslim population outside Muslim-majority countries. However, India's relationship with Pakistan has always been tense and has a direct impact on India-OIC relations, with Pakistan being a founding member of the OIC. India has pushed for the OIC to accept India as a member, arguing that about 11% of all Muslims worldwide live in India. Pakistan opposes India's entry into the OIC.[26][27][28]

The reason for opposition to India's entry into the OIC cited by Pakistan is due to the human rights issues and problems faced by the Kashmiris in the Indian territory of Jammu and Kashmir.[29] India has pushed against the OIC for referring to the state of Jammu and Kashmir as "occupied by India".[26] The Muslim world has been supporting Pakistan rather than India in case of dissentions between the two. However, the role of the OIC concerning the Kashmir issue is that India has the largest Muslim minority and those people have shown desire to join the OIC. While the First Islamic Summit held in 1969 in Rabat did not have the issue of the Kashmir people, granting the 60 million Muslims living in India membership in the OIC was discussed. The head of the Indian delegation, the then ambassador to Morocco, even addressed the gathering. While General Yahya Khan of Pakistan did agree, he showed his extreme displeasure at the induction of non-Muslim representative. Fakhruddin Ali Ahmad, who was to head the Indian delegation was on his way to Rabata. Yahya Khan took a stand against India and threatened to boycott summit which caused a major controversy. As such Indo-Pak differences led Islamabad to keep India out for the final session of the 1969 conference and all summits thereafter.[30]

A suicide attack on Indian Forces on 14 February 2019, followed by Indian Air Strikes subsequently led to a military stand off between India and Pakistan.

Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj was invited in OIC.[31] Pakistan rejected this development and demanded the expulsion of India from the summit citing Kashmir conflict and Indian violation of airspace of Pakistan, while India has stated that it has proofs for its strikes in the form of SAR imagery.[32][33] OIC called emergency meeting of Kashmir contact group on Pakistan's request, the meeting was held on 26 February 2019.[34] OIC advised restraint to Pakistan and India.[35]

For the first time in five decades, the United Arab Emirates invited foreign minister of India Sushma Swaraj to attend the inaugural plenary 46th meeting of OIC foreign ministers held in Abu Dhabi on 1 and 2 March overruling strong objections by Pakistan.[36] Pakistan boycotted the meet objecting to the invitation to India. Swaraj addressed the meet raising concern for spreading terrorism.

On 18 April 2020, the OIC had issued a statement, urging Narendra Modi's government to take urgent steps to "stop the growing tide of Islamophobia" as Hindu nationalists target Indian Muslims, accusing them of spreading the coronavirus disease 2019.[37]

Cartoons of Muhammad

Cartoons of Muhammad, published in a Danish newspaper in September 2005, were found offensive by a number of Muslims. Third Extraordinary Session of the Islamic Summit Conference in December 2005 condemned publication of the cartoons, resulting in broader coverage of the issue by news media in Muslim countries. Subsequently, violent demonstrations throughout the Islamic world resulted in several deaths.[38]

Human rights

OIC created the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam.[7] While proponents claim it is not an alternative to the UDHR, but rather complementary to it, Article 24 states that "all the rights and freedoms stipulated in this Declaration are subject to the Islamic Shari'ah" and Article 25 follows with "the Islamic Shari'ah is the only source of reference for the explanation or clarification of any of the articles of this Declaration." Attempts to have it adopted by the United Nations Human Rights Council have met increasing criticism, because of its contradiction of the UDHR, including from liberal Muslim groups.[39] Critics of the CDHR state bluntly that it is "manipulation and hypocrisy," "designed to dilute, if not altogether eliminate, civil and political rights protected by international law" and attempts to "circumvent these principles [of freedom and equality]."[40][41][42]

Human Rights Watch says that OIC has "fought doggedly" and successfully within the United Nations Human Rights Council to shield states from criticism, except when it comes to criticism of Israel. For example, when independent experts reported violations of human rights in the 2006 Lebanon War, "state after state from the OIC took the floor to denounce the experts for daring to look beyond Israeli violations to discuss Hezbollah's as well." OIC demands that the council "should work cooperatively with abusive governments rather than condemn them." HRW responds that this works with those who are willing to cooperate; others exploit the passivity.[43][44]

The OIC has been criticised for failing to discuss the treatment of ethnic minorities within member countries, such as the oppression of the Kurds in Syria and Turkey, the Ahwaz in Iran, the Hazaras in Afghanistan, the 'Al-Akhdam' in Yemen, or the Berbers in Algeria.[45]

Along with the revisions of the OIC's charter in 2008, the member states created the Independent Permanent Human Rights Commission (IPHRC). The IPHRC is an advisory body, independent from the OIC, composed of eighteen individuals from a variety of educational and professional backgrounds. The IPHRC has the power to monitor human rights within the member states and facilitates the integration of human rights into all OIC mandates. The IPHRC also aids in the promotion of political, civil, and economic rights in all member states.[46]

In September 2017, the Independent Human Rights Commission (IPHRC) of the OIC strongly condemned the human rights violations against the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.[47]

In December 2018, the OIC tentatively raised the issue of China's Xinjiang re-education camps and human rights abuses against the Uyghur Muslim minority.[48] The OIC reversed its position after a visit to Xinjiang, and in March 2019, the OIC issued a report on human rights for Muslim minorities that praised China for "providing care to its Muslim citizens" and looked forward to greater cooperation with the PRC.[49][50]

LGBT rights

In March 2012, the United Nations Human Rights Council held its first discussion of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, following the 2011 passage of a resolution supporting LGBT rights proposed by the Republic of South Africa.[51] Pakistan's representative addressed the session on behalf of the OIC, denouncing the discussion and questioning the concept of sexual orientation, which he said was being used to promote "licentious behaviour ... against the fundamental teachings of various religions, including Islam". He stated that the council should not discuss the topic again. Most Arab countries and some African ones later walked out of the session.[52][53][54]

Nonetheless, OIC members Albania, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, and Sierra Leone have signed a UN Declaration supporting LGBT rights in the General Assembly.[55][56] Whilst Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan and Turkey had legalized homosexuality.

In May 2016, 57 countries including Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates from the Organization of Islamic Cooperation requested the removal of LGBT associations from 2016 High Level Meeting on Ending AIDS, sparking protests by the United States, Canada, the European Union and LGBT communities.[57][58]

Science and technology

The Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) held its first science and technology summit at the level of head of state and government in Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan, on 10–11 September 2017.

Astana Declaration

The Astana Declaration is a policy guidance adopted by OIC members at the Astana Summit. The Astana Declaration commits members to increase investment in science and technology, education, eradicate extreme poverty, and implement UN Sustainable Development Goals.[59]

Non-state terrorism

In 1999, OIC adopted the OIC Convention on Combatting International Terrorism.[60] Human Rights Watch has noted that the definition of terrorism in article 1 describes "any act or threat of violence carried out with the aim of, among other things, imperiling people’s honour, occupying or seizing public or private property, or threatening the stability, territorial integrity, political unity or sovereignty of a state." HRW views this as vague, ill-defined and including much that is outside the generally accepted understandings of the concept of terrorism. In HRW's view, it labels, or could easily be used to label, as terrorist actions, acts of peaceful expression, association, and assembly.[61]

Legal scholar Ben Saul of University of Sydney argues that the definition is subjective and ambiguous and concludes that there is "serious danger of the abusive use of terrorist prosecutions against political opponents" and others.[62]

Furthermore, HRW is concerned by OIC's apparent unwillingness to recognise as terrorism acts that serve causes endorsed by their member states. Article 2 reads: "Peoples' struggle including armed struggle against foreign occupation, aggression, colonialism, and hegemony, aimed at liberation and self-determination." HRW has suggested to OIC that they embrace "longstanding and universally recognised international human rights standards",[61] a request that has as yet not led to any results.

Contradictions between OIC's and other UN members' understanding of terrorism has stymied efforts at the UN to produce a comprehensive convention on international terrorism.[63]

During a meeting in Malaysia in April 2002, delegates discussed terrorism but failed to reach a definition of it. They rejected, however, any description of the Palestinian fight with Israel as terrorism. Their declaration was explicit: "We reject any attempt to link terrorism to the struggle of the Palestinian people in the exercise of their inalienable right to establish their independent state with Al-Quds Al-Shrif (Jerusalem) as its capital." In fact, at the outset of the meeting, the OIC countries signed a statement praising the Palestinians and their "blessed intifada." The word terrorism was restricted to describe Israel, whom they condemned for "state terrorism" in their war with the Palestinian people.[64]

At the 34th Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers (ICFM), an OIC section, in May 2007, the foreign ministers termed Islamophobia "the worst form of terrorism".[65]

Dispute with Thailand

Thailand has responded to OIC criticism of human rights abuses in the Muslim majority provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat in the south of the country. In a statement issued on 18 October 2005, secretary-general Ihsanoglu vocalised concern over the continuing conflict in the south that "claimed the lives of innocent people and forced the migration of local people out of their places".[66] He also stressed that the Thai government's security approach to the crisis would aggravate the situation and lead to continued violence.

On 18–19 April 2009, the exiled Patani leader Abu Yasir Fikri (see Patani United Liberation Organisation) was invited to the OIC to speak about the conflict and present a solution to end the violence between the Thai government and the ethnically Malay Muslims living in the socioeconomically neglected south, that has been struggling against Thai assimilation policy and for self governance since it became annexed by Thailand in 1902. Fikri presented a six-point solution at the conference in Jiddah that included obtaining the same basic rights as other groups when it came to right of language, religion, and culture. He also suggested that Thailand give up its discriminatory policies against the Patani people and allow Patani to at least be allowed the same self-governing rights as other regions in Thailand already have, citing that this does not go against the Thai constitution since it has been done in other parts of Thailand and that it is a matter of political will.[67] He also criticised the Thai government's escalation of violence by arming and creating Buddhist militia groups and questioned their intentions. He added Thai policies of not investigating corruption, murder, and human rights violations perpetrated by Bangkok-led administration and military personnel against the Malay Muslim population was an obstacle for achieving peace and healing the deep wounds of being treated as third-class citizens.[67][68]

Thailand responded to this criticism over its policies. The Thai foreign minister, Kantathi Suphamongkhon, said: "We have made it clear to the OIC several times that the violence in the deep South is not caused by religious conflict and the government grants protection to all of our citizens no matter what religion they embrace." The Foreign Ministry issued a statement dismissing the OIC's criticism and accusing it of disseminating misperceptions and misinformation about the situation in the southern provinces. "If the OIC secretariat really wants to promote the cause of peace and harmony in the three southern provinces of Thailand, the responsibility falls on the OIC secretariat to strongly condemn the militants, who are perpetrating these acts of violence against both Thai Muslims and Thai Buddhists."[66][69][70] HRW[71] and Amnesty International[68] have echoed the same concerns as OIC, rebuffing Thailand's attempts to dismiss the issue.

Notable meetings

A number of OIC meetings have attracted global attention.

Ninth meeting of PUOICM

The ninth meeting of Parliamentary Union of the OIC member states (PUOICM) was held on 15 and 16 February 2007 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.[72] The speaker of Malaysia's House of Representatives, Ramli bin Ngah Talib, delivered a speech at the beginning of the inaugural ceremony. OIC secretary-general Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu said prior to the meeting that one main agenda item was stopping Israel from continuing its excavation at the Western Wall near the Al-Aqsa Mosque, Islam's third holiest site.[73] The OIC also discussed how it might send peacekeeping troops to Muslim states, as well as the possibility of a change in the name of the body and its charter.[73] Additionally, return of the sovereignty right to the Iraqi people along with withdrawal of foreign troops from Iraq was another one of the main issues on the agenda.[74]

Pakistani Foreign Minister Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri told reporters on 14 February 2007 that the secretary general of OIC and foreign ministers of seven "like-minded Muslim countries" would meet in Islamabad on 25 February 2007 following meetings of President Musharraf with heads of key Muslim countries to discuss "a new initiative" for the resolution of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Kasuri said this would be a meeting of foreign ministers of key Muslim countries to discuss and prepare for a summit in Makkah Al Mukarramah to seek the resolution of the Arab–Israeli conflict.[75]

IPHRC Trip to Washington DC

In December 2012, the IPHRC met in Washington, DC for the first time. The IPHRC held meetings at the National Press Club, Capitol Hill and Freedom House discussing the issues of human rights defense in the OIC member states. During their roundtable discussion with Freedom House the IPHRC emphasised the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the rejection of the Cairo Declaration by the OIC.[76]

Observer Status dispute

The September 2014's high-level Summit of the OIC, in New York, ended without adopting any resolutions or conclusions, for the first time in several years in the modern history of the organization, due to a dispute regarding the status of one of its Observer states. Egypt, Iran and the United Arab Emirates have demanded that the OIC remove the term 'Turkish Cypriot State' in reference to the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which has observer status within the organization. Egypt's president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi insisted that any reference to the "Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus or Turkish Cypriot State" was unacceptable and was ultimately the reason for the OIC not adopting any resolutions or conclusions in the 2014 summit.[77][78][79]

Structure and organisation

The OIC system consists of:

Islamic Summit

The largest meeting, attended by the kings and the heads of state and government of the member states, convenes every three years. The Islamic Summit takes policy decisions and provide guidance on all issues pertaining to the realisation of the objectives as provided for in the Charter and consider other issues of concern to the Member States and the Ummah.[80]

Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers

Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers meets once a year to examine a progress report on the implementation of its decisions taken within the framework of the policy defined by the Islamic Summit.

Secretary General

The Secretary General is elected by the Council of Foreign Ministers for a period of five years, renewable once. The Secretary-General is elected from among nationals of the Member States in accordance with the principles of equitable geographical distribution, rotation and equal opportunity for all Member States with due consideration to competence, integrity and experience.[81]

Permanent Secretariat

The Permanent Secretariat is the executive organ of the Organisation, entrusted with the implementation of the decisions of the two preceding bodies, and is located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The Secretary General of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) is Dr. Yousef A. Al-Othaimeen. He received his office on, Tuesday, 29 November 2016

Subsidiary organisations

- The Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries, in Ankara, Turkey

- The Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA), located in Istanbul, Turkey

- The Islamic University of Technology, located in Dhaka, Bangladesh

- The Islamic Centre for the Development of Trade, located in Casablanca, Morocco

- The Islamic Fiqh Academy, located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- The Islamsate Islamic Network, located at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- The Executive Bureau of the Islamic Solidarity Fund and its Waqf, located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- The Islamic University in Niger, located in Say, Niger.

- The Islamic University in Uganda, located in Mbale, Uganda.

- The Tabriz Islamic Arts University, located in Tabriz, Iran.

Specialised institutions

- The Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (ISESCO), located in Rabat, Morocco.

- The Islamic States Broadcasting Organisation (ISBO) and the International Islamic News Agency (IINA), located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Affiliated institutions

- Islamabad Chamber of Commerce & Industry (ICCI), located in Karachi, Pakistan.

- World Islamic Economic Forum (WIEF), located in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Organisation of Islamic Capitals and Cities (OICC), located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

- Sports Federation of Islamic Solidarity Games, located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- Islamic Committee of the International Crescent (ICIC), located in Benghazi, Libya.

- Islamic Shipowners Association (ISA), located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

- World Federation of International Arab-Islamic Schools, located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

- International Association of Islamic Banks (IAIB), located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

- Islamic Conference Youth Forum for Dialogue and Cooperation (ICYF-DC), located in Istanbul, Turkey.

- General Council for Islamic Banks and Financial Institutions (CIBAFI), located in Manama, Bahrain.

- Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries (SMIIC), located in Istanbul, Turkey.[82]

Criticism

OIC has been criticised by many Muslims for its lack of real engagement and solutions for Muslim countries in crisis.[83] It is said to have made progress in social and academic terms but not politically.[84]

In 2020, Pakistan's Minister of Foreign Affairs SM Qureshi criticized OIC for its stand with regards to Kashmir issue, stating with Pakistan might consider to call a meeting of Islamic countries that are ready to stand with them on the issue. This comment invited immediate retaliation from Saudi Arabia, where the latter forced Pakistan to repay 1 Billion dollars from the 3 Billion dollars loan it had taken in 2018 and by also ending its oil supply credit.[85]

Secretaries-General

| No. | Name | Country of origin | Took office | Left office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tunku Abdul Rahman | 1970 | 1974 | |

| 2 | Hassan Al-Touhami | 1974 | 1975 | |

| 3 | Amadou Karim Gaye | 1975 | 1979 | |

| 4 | Habib Chatty | 1979 | 1984 | |

| 5 | Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada | 1984 | 1988 | |

| 6 | Hamid Algabid | 1988 | 1996 | |

| 7 | Azeddine Laraki | 1996 | 2000 | |

| 8 | Abdelouahed Belkeziz | 2000 | 2004 | |

| 9 | Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu | 2004 | 2014 | |

| 10 | Iyad bin Amin Madani | 2014 | 2016 | |

| 11 | Yousef Al-Othaimeen | 2016 | Current | |

Islamic Summits

| Number | Date | Country | Place |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 22–25 September 1969 | Rabat | |

| 2nd[87] | 22–24 February 1974 | Lahore | |

| 3rd[88] | 25–29 January 1981 | Mecca & Ta’if | |

| 4th | 16–19 January 1984 | Casablanca | |

| 5th[89] | 26–29 January 1987 | Kuwait City | |

| 6th[90] | 9–11 December 1991 | Dakar | |

| 7th | 13–15 December 1994 | Casablanca | |

| 1st Extraordinary | 23–24 March 1997 | Islamabad | |

| 8th | 9–11 December 1997 | Tehran | |

| 9th | 12–13 November 2000 | Doha | |

| 2nd Extraordinary[91] | 4–5 March 2003 | Doha | |

| 10th | 16–17 October 2003 | Putrajaya | |

| 3rd Extraordinary | 7–8 December 2005 | Mecca | |

| 11th[92] | 13–14 March 2008 | Dakar | |

| 4th Extraordinary[93] | 14–15 August 2012 | Mecca | |

| 12th[94] | 6–7 February 2013 | Cairo | |

| 5th Extraordinary[95] | 6–7 March 2016 | Jakarta | |

| 13th[96] | 14–15 April 2016 | Istanbul | |

| 6th Extraordinary | 13 December 2017 | Istanbul | |

| 7th Extraordinary | 18 May 2018 | Istanbul | |

| 14th[97] | 31 May 2019 | Mecca |

See also

- Azerbaijan-the OIC relations

- Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam

- D-8 Organization for Economic Cooperation

- Flag of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

- Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition

- Islamic Reporting Initiative

- Islamic University of Technology

- List of largest cities in Organisation of Islamic Cooperation member countries

- Demographics of the member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

- Pakistan and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

References

- The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. December 2012. "The Global Religious Landscape: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Major Religious Groups as of 2010." DC: Pew Research Center. Article.

- About OIC. Oic-oci.org. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Ciment, James; Hill, Kenneth, eds. (6 December 2012). Encyclopedia of Conflicts Since World War II, Volume 1. Routledge. pp. 185–6. ISBN 9781136596148. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- LIEBER, DOV (22 August 2017). "PA, Hamas [allege] Jews planned 1969 burning of Al-Aqsa Mosque". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "The organization 'Islamic Conference' (OIC)". elibrary. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Esposito, 1998, p.164.

- "Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, 5 August 1990, U.N. GAOR, World Conf. on Hum. Rts., 4th Sess., Agenda Item 5, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.157/PC/62/Add.18 (1993) [English translation]". University of Minnesota. 5 August 1990. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "OIC Charter". Ch 1, Art 1, Sect 7. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "OIC to hold conference on refugees in Muslim world in Turkmenistan". Zaman. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012.

- "OIC RIGHTLY CHANGES ITS NAME". Pakistan Observer. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014.

- Alsharif, Asma (16 August 2012). "Organization of Islamic Cooperation suspends Syria". U.S. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "وب سایتهای ایرنا - Irna". Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Feller, Ben (2 June 2007). "Bush to Name Envoy to Islamic Conference". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 December 2007.

- "Arsalan Suleman". US Department of State. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "United Condemnations". Snopes. 3 December 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Muslims condemn Dutch lawmaker's film". CNN. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "OIC supports military action in Yemen". Arab News. 27 March 2015.

- "OIC calls for ban on Israeli products".

- "islamic office for the boycott of israel" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2015.

- "OIC proposes severing ties with countries that recognise Jerusalem as Israel's capital". Middle East Monitor. 10 February 2014. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- http://www.mfa.gov.tr/site_media/html/oic-extraordinary-summit-istanbul-declaration-on-freedom-for-al-quds.pdf

- "UN condemns Israeli PM's West Bank annexation plans". CBC News. 11 September 2019.

- "Religion Data - Population of Hindu / Muslim / Sikh / Christian - Census 2011 India". census2011.co.in. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "Muslim population growth slows". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "India has 72.8% Hindus, 18 to 20% Muslims, says 2011 census data on religion". Firstpost. 26 August 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Wahab, Siraj (30 June 2011). "OIC urged to press India on Kashmir issue". Arab News. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Chickrie, Raymond (23 January 2011). "Eight Countries Seek OIC Membership". Caribbean Muslims. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- "'Pak will match India weapons'". The Indian Express. 3 July 2005. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- Orakzai, S. (2010). "Organisation of The Islamic Conference and Conflict Resolution: Case Study of the Kashmir Dispute. Pakistan Horizon, 63(2)": 83. JSTOR 24711087. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sager, Abdulaziz (10 October 2009). "Why not India in OIC". Kjaleej Times. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "India's 'global stature' and 'islamic component' help it get OIC invite". The Economic Times. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Gupta, Kriti (2 March 2019). "Indian Airforce Force official statement". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Orakzai, S. (2010). "Organisation of The Islamic Conference and Conflict Resolution: Case Study of the Kashmir Dispute. Pakistan Horizon, 63(2)": 88. JSTOR 24711087. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Siddiqui, Naveed (25 February 2019). "OIC calls emergency meeting of Kashmir contact group on Pakistan's request". Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "OIC slams strikes, advises India and Pakistan restraint". The Times of India. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Roche, Elizabeth (24 February 2019). "India invited as 'guest of honour' to OIC meet, Sushma Swaraj to attend". Live Mint. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Why Arabs are speaking out against Islamophobia in India". Al Jazeera. 30 April 2020.

- Howden, Daniel; Hardaker, David; Castle, Stephen (10 February 2006). "How a meeting of leaders in Mecca set off the cartoon wars around the world". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- "Human Rights Brief" United Nations Update Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 10 March 2009.

- Fatema Mernissi: Islam and Democracy, Cambridge 2002, Perseus Books, p. 67.

- Ann Mayer, "An Assessment of Human Rights Schemes," in Islam and Human Rights, p. 175. Westview 1999, Westview Press.

- Robert Carle: "Revealing and Concealing: Islamist Discourse on Human Rights," Human rights review, vol:6, No 3 April–June 2005.

- How to Put U.N. Rights Council Back on Track Human Rights Watch, 2 November 2006.

- The UN Human Rights Council Human Rights Watch Testimony Delivered to the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 25 July 2007.

- Kymlicka, Will (2007). Multicultural Odysseys: Navigating the New International Politics of Diversity. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-19-928040-7. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- CISMAS, I. (2011). "Statute of the OIC independent permanent human rights commission, introductory note. International Legal Materials, 50(6)": 1148–1160. doi:10.5305/intelegamate.50.6.1148. hdl:1893/21712. JSTOR 10.5305/intelegamate.50.6.1148. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "OIC condemns abuses against Rohingya in Myanmar". Arab News. 5 September 2017.

- "A wall of silence around China's oppression of its Muslim minority is starting to crumble". Business Insider. 2 March 2019.

- Perlez, Jane (8 April 2019). "With Pressure and Persuasion, China Deflects Criticism of Its Camps for Muslims". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- RESOLUTIONS ON MUSLIM COMMUNITIES AND MUSLIM MINORITIES IN THE NON-OIC MEMBER STATES

- "List of Panel Discussions to take place during 19th session" (PDF).

- Evans, Robert (8 March 2012). "Islamic states, Africans walk out on UN gay panel". Reuters. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Solash, Richard (7 March 2012). "Historic UN Session on Gay Rights Marked By Arab Walkout". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- South Africa leads United Nations on gay rights | National | Mail & Guardian. Mg.co.za (9 March 2012). Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- "Archived copy". Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- Over 80 Nations Support Statement at Human Rights Council on LGBT Rights » US Mission Geneva. Geneva.usmission.gov. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- James Rothwell (18 May 2016). "Muslim countries ban gay and transgender reps from United Nations meeting on Aids". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Nichols, Michelle (4 April 2013). "Muslim states block gay groups from U.N. AIDS meeting; U.S. protests". Reuters. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- "ASTANA DECLARATION". OIC. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "OIC Convention on Combating International Terrorism". OICUN. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- Organisation of the Islamic Conference: Improve and Strengthen the 1999 OIC Convention on Combating International Terrorism Human Rights Watch 11 March 2008.

- Ben Saul: Branding Enemies: Regional Legal Responses to Terrorism in Asia ‘'Asia-Pacific Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law, 2008'’ Sydney Law School Legal Studies Research Paper No. 08/127, October 2008.

- Patrick Goodenough: UN Anti-Terror Effort Bogged Down Over Terrorism Definition CNSNew, 2 September 2008. Archived 7 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- The OIC's blind eye to terror The Japan Times 9 April 2002.

- ‘Islamophobia Worst Form of Terrorism’ Arab News 17 May 2007.

- "Ihsanoglu urges OIC Member States to accord greater attention to Muslim minority issues". Patanipost.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "Welcome to Patani Post! PULO President invited to speak at OIC meeting 18–19 April 2009". Patani Post. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "Thailand". Amnesty International. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- Archived 23 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "OIC Resolution". Patani Post. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "Thailand". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Malaysian National News Agency". Bernama. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- Archived 6 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Upcoming Event: Roundtable Discussion with the OIC's Human Rights Commission". Freedom House. 13 December 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- The World Bulletin news: Egypt's Sisi demands Turkish Cypriots removed from OIC

- Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Egypt's Sisi tells Turks to get out of Cyprus

- OIC says «NO» to «Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus»

- Welcome to Organisation of Islamic Cooperation official website. Oic-oci.org. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Welcome to Organisation of Islamic Cooperation official website. Oic-oci.org. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- "About SMIIC". Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- "OIC: 40 Years of Frustrations | | Al Jazeera". 1 August 2018. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- "OIC: 40 Years of Frustrations | | Al Jazeera". 1 August 2018. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- Harsha Kakar (11 August 2020). "Pakistan isolated on Kashmir". The Statesman. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "General Secretariat". oic-oci.org.

- "Second Islamic summit conference" (PDF). Formun. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "Mecca Declaration". JANG. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Resolution of the Fifth Islamic Summit Conference". IRCICA. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "Dakar Declaration" (PDF). IFRC. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Darwish, Adel (1 April 2003). "OIC meet in Doha: mudslinging dominated the OIC conference in Qatar". Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Shah, S. Mudassir Ali (12 March 2008). "Karzai flies to Senegal for 11th OIC summit". Pajhwok Afghan News. Kabul. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Knipp, Kersten (15 August 2012). "Islamic group hopes to limit Syrian conflict". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Arrott, Elizabeth (6 February 2013). "Islamic Summit Leaders Urge Action on Mali, Syria". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Karensa, Edo (6 March 2016). "OIC Extraordinary Summit on Palestine Kicks Off in Jakarta". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cooperation, Organization of Islamic (19 May 2019). "The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques chairs the 14th ordinary Islamic Summit". The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques chairs the 14th ordinary Islamic Summit. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

Further reading

- Ankerl, Guy Coexisting Contemporary Civilisations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva, INUPress, 2000, ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Al-Huda, Qamar. "Organisation of the Islamic Conference." Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Edited by Martin, Richard C. Macmillan Reference, 2004. vol. 1 p. 394, 20 April 2008.

External links

Media related to Organisation of Islamic Cooperation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Organisation of Islamic Cooperation at Wikimedia Commons