British government response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Her Majesty's Government responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom in various ways. Because of devolution, following the arrival of coronavirus disease 2019 on 31 January 2020, the different home nations' administrative responses to the pandemic have been different to one another; the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government, and the Northern Ireland Executive have produced different policies to those that apply in England. The National Health Service is the publicly funded healthcare system of Britain, and has separate branches for each of its four nations.

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The main responsibility for public health and healthcare in the United Kingdom lies with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), with responsibility devolved to respective governments in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. For England, the DHSC has responsibility for Public Health England (an executive agency) and NHS England (a non-departmental public body); in England and Wales, for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; and for the British Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The Chief Medical Officer (CMO) for England is the British Government's senior medical adviser, while the CMOs for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland are the senior medical advisers in their respective home nations. The Government Chief Scientific Adviser is the senior scientific adviser to the British Cabinet and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. A Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for COVID-19 Vaccine Deployment was appointed in November 2020.

Responsibility for health policy is devolved in Scotland to the Health and Social Care Directorates, which oversees Public Health Scotland and NHS Scotland, for which the Scottish Government's Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, is responsible to the Scottish Parliament. In Wales, responsibility for Public Health Wales and NHS Wales is devolved to the Welsh Government's Minister for Health and Social Services, Vaughan Gething, who is responsible to the Welsh Parliament. For the Northern Ireland Executive's Department of Health, overseeing Health and Social Care and the Public Health Agency, the Minister of Health Robin Swann is responsible to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

The British Armed Forces began two military operations in response to the pandemic: Operation Rescript – which spanned the response in the British Islands – and Operation Broadshare, which organised the military response in the British Overseas Territories and the overseas military bases of the United Kingdom.

Prior pandemic response plans

The UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy was published in 2011 and updated in 2014,[1] alongside a review of the available medical and social countermeasures.[2] Pandemic flu guidance was published in 2013 and updated in 2017, covering guidance for local planners, business sectors, and an ethical framework for the government response. The guidance stated:[3]

There are important differences between 'ordinary' seasonal flu and pandemic flu. These differences explain why we regard pandemic flu as such a serious threat. Pandemic influenza is one of the most severe natural challenges likely to affect the UK.

In 2016, the government carried out Exercise Cygnus, a three-day simulation of a widespread flu outbreak. A report compiled the following year by Public Health England (but not made public) found deficiencies in emergency plans, lack of central oversight and difficulty managing capacity in care homes.[4] In June 2020, the Permanent Secretary at the Treasury Tom Scholar and the Cabinet Office Permanent Secretary Alex Chisholm told the Public Accounts Committee that the civil service did not subsequently create a plan for dealing with the pandemic's effects on the economy.[5]

Regulations and legislation

The government published the Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020 on 10 February 2020, a statutory instrument covering the legal framework behind the government's initial containment and isolation strategies and its organisation of the national reaction to the virus for England.[6] Other published regulations include changes to Statutory sick pay (into force on 13 March),[7] and changes to Employment and Support Allowance and Universal Credit (also 13 March).[8]

On 19 March, the government introduced the Coronavirus Act 2020, which grants the government discretionary emergency powers in the areas of the NHS, social care, schools, police, the Border Force, local councils, funerals and courts.[9] The act received royal assent on 25 March 2020.[10]

Closures to pubs, restaurants and indoor sports and leisure facilities were imposed in England via the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Business Closure) (England) Regulations 2020.[11]

The restrictions on movements, except for allowed purposes, were:

- Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020[12] (and subsequent amendments)

- Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Restrictions) (Scotland) Regulations 2020[13]

- Health Protection (Coronavirus Restrictions) (Wales) Regulations 2020[14]

- The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020[15]

In England from 15 June 2020, the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Wearing of Face Coverings on Public Transport) (England) Regulations 2020 required travellers on public transport to wear a face covering.[16]

On 25 June 2020, the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 was enacted to provide additional protections to companies in financial difficulty as a result of the impacts of the pandemic.[17]

Initial response

The first published government statement on the coronavirus situation in Wuhan was released on 22 January 2020 by the Department of Health and Social Care and Public Health England.[19] Guidance has progressed in line with the number of cases detected and changes in where affected people have contracted the virus, as well as with what has been happening in other countries.[20] In February, Chief Medical Officer (CMO) to the British government, Chris Whitty said "we basically have a strategy which depends upon four tactical aims: the first one is to contain; the second of these is to delay; the third of these is to do the science and the research; and the fourth is to mitigate so we can brace the NHS".[21] These aims equate to four phases; specific actions involved in each of these phases are:

- Contain: detect early cases, follow up close contacts, and prevent the disease from taking hold in this country for as long as is reasonably possible

- Delay: slow the spread within the UK, and (if it does take hold) lower the peak impact and push it away from the winter season

- Research: better understand the virus and the actions that will lessen its effect on the British population; innovate responses including diagnostics, drugs, and vaccines; use the evidence to inform the development of the most effective models of care

- Mitigate: provide the best care possible for people who become ill, support hospitals to maintain essential services and ensure ongoing support for people ill in the community, to minimise the overall impact of the disease on society, public services and on the economy.[22]

The four CMOs of the home nations raised the UK's risk level from low to moderate on 30 January 2020, upon the WHO's announcement of the disease as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[23][24] As soon as cases appeared in the UK on 31 January 2020, a public health information campaign, similar to the previous "Catch it, Bin it, Kill it" campaign, was launched in the UK, to advise people how to lessen the risk of spreading the virus.[24] Travellers from Hubei province in China, including the capital Wuhan, were advised to self-isolate, "stay at home, not go to work, school or public places, not use public transport or taxis; ask friends, family members or delivery services to do errands",[25] and call NHS 111 if they had arrived in the UK in the previous 14 days, regardless of whether they were unwell or not.[24] Further cases in early February prompted the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Matt Hancock, to announce the Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020.[23] Daily updates have been published by the Department of Health and Social Care.[23] NHS Digital in the meanwhile, have been collecting data.[26]

On 25 February 2020, the British CMOs advised all travellers (unwell or not) who had returned to the UK from Hubei province in the previous 14 days, Iran, specific areas designated by the Italian government as quarantine areas in northern Italy, and special care zones in South Korea since 19 February, to self-isolate and call NHS 111.[27] This advice was also advocated for any person with flu-like symptoms and a history of travelling from Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and areas in Italy north of Pisa, Florence and Rimini, returning to the UK since 19 February. Later, self-isolation was recommended for anyone returning from any part of Italy from 9 March.[23][27]

Initially, Prime Minister Boris Johnson largely kept Britain open, resisting the kind of lockdowns seen elsewhere in Europe. In a speech on 3 February, Johnson's main concern was that the "coronavirus will trigger a panic and a desire for market segregation that go beyond what is medically rational to the point of doing real and unnecessary economic damage".[28] On 11 February, a "senior member of the government" told the ITV journalist Robert Peston that "If there is a pandemic, the peak will be March, April, May" and, further, that "the risk is 60% of the population getting it. With a mortality rate of perhaps just over 1%, we are looking at not far off 500,000 deaths".[29] On 8 March, Peston reported that the government believed the Italian government's approach to lockdown to be based on "several of the populist - non-science based - measures that aren't any use. They're who not to follow".[30]

On 11 March, the Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England Jenny Harries said that the government was "following the science" by not banning mass gatherings. She also said, on face masks, "If a healthcare professional hasn't advised you to wear a face mask... it's really not a good idea and doesn't help".[31] On 13 March, British government Chief Scientific Adviser Patrick Vallance told BBC Radio 4 one of "the key things we need to do" is to "build up some kind of herd immunity so more people are immune to this disease and we reduce the transmission".[32] This involves enough people getting infected, upon which they develop immunity to the disease.[33][34] Vallance said 60% of the UK's population will need to become infected for herd immunity to be achieved.[35][34] This stance was criticised by experts who said it would lead to hundreds of thousands of deaths and overwhelm the NHS. More than 200 scientists urged the government to rethink the approach in an open letter.[36] Subsequently, Health Secretary Matt Hancock said that herd immunity was not a plan for the UK, and the Department of Health and Social Care said that "herd immunity is a natural by-product of an epidemic".[37] On 26 March, Deputy Chief Medical Officer Jenny Harries said that testing and contact tracing was no longer "an appropriate mechanism as we go forward".[38] On 4 April, The Times reported that Graham Medley, a member of the UK government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), was still advocating a "herd immunity" strategy.[39] There was a letter published in The Lancet on 17 March calling on the government to openly share its data and models as a matter of urgency.[40]

On 2 March, Johnson said in an interview with BBC News: "The most important thing now is that we prepare against a possible very significant expansion of coronavirus in the UK population". This came after the 39th case in the UK was confirmed and over a month after the first confirmed case in the UK.[41] The same day, a BBC One programme Coronavirus: Everything You Need to Know addressed questions from the public on the outbreak.[42] The following day, the Coronavirus Action Plan was unveiled.[23] The next day, as the total number of cases in the UK stood at 51, the government declared the coronavirus pandemic as a "level 4 incident",[43] permitting NHS England to take command of all NHS resources.[43][44] Planning has been made for behaviour changing publicity including good hygiene and respiratory hygiene ("catch it, bin it, kill it"),[45] a measure designed to delay the peak of the infection and allow time for the testing of drugs and initial development of vaccines.[22] Primary care has been issued guidance.[46]

Public Health England has also been involved with efforts to support the British Overseas Territories against the outbreak.[47][48]

On 16 March, the British government started holding daily press briefings. The briefings were to be held by the Prime Minister or government ministers and advisers. The government had been accused of a lack of transparency over their plans to tackle the virus.[49] Daily briefings were also held by the devolved administrations of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.[50] The speakers at the daily press briefings were accompanied by sign language interpreters. British sign language is a recognised language in Scotland and Wales, with interpreters standing 2 metres behind Ministers. Northern Ireland's briefings had both British and Irish Sign Language interpreters who were shown on a small screen in the press conference room. The British government briefing did not have an interpreter in the room or on a screen leading to a Twitter campaign about the issue. The government reached an agreement to have the press conferences signed on the BBC News Channel and on iPlayer in response to the campaign.[51] In response to this a petition was created by Sylvia Simmonds that required the government to use sign language interpreters for emergency announcements.[52] Legal firm Fry Law looked to commence court proceedings as they said the government had broken the Equality Act 2010, but also said that the government was doing the bare minimum and were crowdfunding to cover the government's legal costs if they lost.[51]

On 17 March 2020, Johnson announced in a daily news conference that the government "must act like any wartime government and do whatever it takes to support our economy".[53]

Progression between phases

On 12 March, the government announced it was moving out of the contain phase and into the delay phase of the response to the coronavirus outbreak. The announcement said that in the following weeks, the government would introduce further social distancing measures for older and vulnerable people, and asking them to self-isolate regardless of symptoms. Its announcement said that if the next stage were introduced too early, the measures would not protect at the time of greatest risk but they could have a huge social impact. The government said that its decisions were based on careful modelling and that government measures would only be introduced that were supported by clinical and scientific evidence.[54]

Classification of the disease

From 19 March, Public Health England, consistent with the opinion of the Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens, no longer classified COVID-19 as a "High consequence infectious disease" (HCID). This reversed an interim recommendation made in January 2020, due to more information about the disease confirming low overall mortality rates, greater clinical awareness, and a specific and sensitive laboratory test, the availability of which continues to increase. The statement said "the need to have a national, coordinated response remains" and added, "this is being met by the government's COVID-19 response". This meant cases of COVID-19 are no longer managed by HCID treatment centres only.[55]

First national lockdown

The slogan "Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives" was first suggested internally in a government conference call on 19 March, days before they imposed a full national lockdown. The slogan was introduced concurrently with the national lockdown imposed on 23 March, ordering the public against undergoing non-essential travel and ordering many public amenities to close.

Essential travel included food shopping, exercise once per day, medical attention, and travelling for necessary work, which included those working in the healthcare, journalism, policing, and food distribution industries.[56] To ensure that the lockdown was obeyed, all shops selling “nonessential goods,” as well as playgrounds, libraries, and places of worship, were to be closed.[57] Gatherings of more than two people in public were also banned, including social events, such as weddings, baptisms and other ceremonies, but excluding funerals.[58]

The stay-at-home order was announced by the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, in a television broadcast. It was initially expected to last at least three weeks, superseding the government's guidance for the public to go about their normal lives while remembering to wash their hands thoroughly.[59] The "Stay Home" slogan appeared on the lecterns that speakers stood behind at the press conferences. It was often seen in capital letters, on a yellow background, with a red and yellow tape border. The government commissioned and broadcast millions of radio, television,[59] newspaper and social media adverts. These were often accompanied by photographs of healthcare workers wearing personal protective equipment, including face masks.[60]

On 23 March, a 20,000-strong military task force, named the COVID Support Force, was launched to provide support to public services and civilian authorities. Two military operations — Operation Rescript and Operation Broadshare — commenced to address the outbreak within the United Kingdom and its overseas territories.[61]

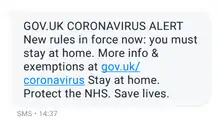

On 24 March, all major mobile telephony providers, acting upon a government request, sent out an SMS message to each of their customers, with advice on staying isolated.[62] This was the first ever use of the facility.[62] Although the government in 2013 endorsed the use of Cell Broadcast to send official emergency messages to all mobile phones, and has tested such a system, it has never actually been implemented. Backer Toby Harris said the government had not yet agreed upon who would fund and govern such a system.[63][64]

On 27 March, Johnson said he had contracted coronavirus and was self-isolating, and that he would continue to lead the government's response to coronavirus through video conference.[65] On the evening of 5 April the Prime Minister was admitted to hospital for tests.[66] The next day he was moved to the intensive care unit at St Thomas' Hospital, and First Secretary of State Dominic Raab deputised for him.[67] On 11 July 2020, the MPs urged the Prime Minister to clarify on wearing masks, after he hinted a day earlier that it could become compulsory to wear them in shops.[68]

Lifting the first lockdown and regional restrictions

In mid-April, a member of the Cabinet told The Telegraph that there was no exit plan yet.[69] Several members of the British government stated that it was not possible to draw up a definitive plan on how to exit lockdown as it is based on scientific advice.[70]

In early May, research was published which concluded that if the most vulnerable (the elderly and those with certain underlying illnesses) were completely shielded, the lockdown could mostly be lifted, avoiding "a huge economic, social and health cost", without significantly increasing severe infections and deaths.[71] It also recommended regular testing and contact tracing.[72][73]

On 8 May the Welsh government relaxed restrictions on exercise and allowed some garden centres and recycling facilities would reopen.[74] Nicola Sturgeon stated that she wanted all nations to make changes together as it would give the public a clear and consistent message.[75] Boris Johnson acknowledged different areas move at slightly different speeds with actions based on the science for each area.[76] Scotland announced a similar measure in terms on exercise as Wales, to go live on the same day.[77]

.png.webp)

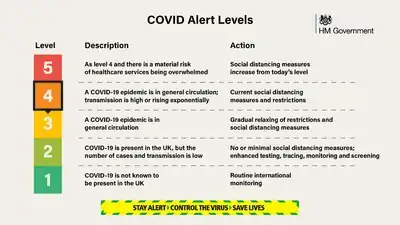

Johnson made a second televised address on 10 May, changing the slogan from "Stay at Home" to "Stay Alert". "Stay Home" was reported as being at the core of the government's communications until being phased out around this time.[78] The full "Stay Alert, Control the Virus, Save Lives" would later be followed by "Hands, Face, Space".[79][80] Johnson also outlined on the 10 May address how restrictions might end and introduced a COVID-19 warning system.[81] Additionally measures were announced stating that the public could exercise more than once a day in outdoor spaces such as parks, could interact with others whilst maintaining social distance and drive to other destinations from 13 May in England.[82] This was leaked to the press[83][84] and criticised by leaders and ministers of the four nations, who said it would cause confusion.[85] The leaders of Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales said they would not adopt the new slogan.[86][87] The Welsh Health Minister Vaughan Gething said that the four nations had not agreed to it and the Scottish Health Secretary Jeane Freeman said that they were not consulted on the change.[88][89] Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said that the new message "lacked clarity".[90] The Guardian were told that neither Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer for England, or Sir Patrick Vallance, government's chief scientific adviser, had given the go ahead for the new slogan. Witty later said at a Downing Street press conference that "Neither Sir Patrick nor I consider ourselves to be comms experts, so we're not going to get involved in actual details of comms strategies, but we are involved in the overall strategic things and we have been at every stage." The slogan was criticised by members of SAGE.[91] Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said: "We mustn't squander progress by easing up too soon or sending mixed messages. People will die unnecessarily."[92]

The next day the government published a 60-page roadmap of what exiting lockdown could look like.[93] A document was additionally published outlining nine points which applied to England, with an update of measures from 13 May.[94] As the rules between England and Wales were different in terms of exercise, many officials warned against the public driving to destinations in Wales for exercise.[95] The Counsel General for Wales, Jeremy Miles, said visitors could be fined if they drove into Wales for leisure.[88] Sturgeon gave a similar warning about driving into Scotland.[96] She additionally said that politicians and the media must be clear about what they are saying for different parts of the UK after Johnson's address did not state which measures only applied to England.[82][97][98] On 17 May, Labour leader Keir Starmer called for a 'four-nation' unified approach.[99] Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham said that there was a risk of national unity in ignoring the different demands of regions in England.[100][101] Boris Johnson acknowledged the frustrations in some of the rules and said that "complicated messages were needed during the next phase of the response and as restrictions changed".[102]

The Northern Ireland Executive published a five-stage plan for exiting lockdown on 12 May, but unlike the plans announced in England the plans did not include any dates of when steps may be taken.[103][104][86] An announcement was made on 14 May that garden centres and recycling centres would reopen on Monday in the first steps taken to end the lockdown in Northern Ireland.[105][103]

On 15 May, Mark Drakeford announced a traffic light plan to remove the lockdown restrictions in Wales, which would start no earlier than 29 May.[106][107] On 20 June 2020, a group of cross-party MPs wrote a letter to the government, urging them to consider a four-day working week for the UK after the pandemic.[108]

While nationwide lockdown measures were gradually relaxed throughout the summer, including a shift towards regional measures such as those instituted in Northern England in July,[109] lockdown easing plans were delayed at the end of July due to rises in case numbers,[110] and measures were increased once more following the resurgence of the virus nationwide starting in early September.[111][112] On 14 August the Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak urged people to return to offices, cafés and restaurants.[113] On 27 August Boris Johnson launched a campaign emphasising the benefits to the public of returning to the office instead of working from home.[114]

On 9 September 2020, the British government announced the banning of social gatherings of more than six people, which was to be implemented from 14 September, amidst rising cases of coronavirus. A £100 fine was initiated to be imposed on the people who fail to comply, doubling on each offense up to a maximum of £3,200.[115] Boris Johnson chose not to follow his scientific advisers' advice for the first time on 21 September when he did not impose a short "circuit-breaker" lockdown as advised by SAGE.[116]

By 1 October 2020, around a quarter of the population of the United Kingdom, about 16.8 million people, were subject to local lockdown measures with some 23% of people in England, 76% of people in Wales and 32% of people in Scotland being in local lockdown.[117] On 12 October, Johnson unveiled a three-tier approach for England, in which local authorities were divided into different levels of restrictions.[118]

Second national lockdown

Johnson announced in a press conference on 31 October that England would enter a second national lockdown which would go on for four weeks. He said that to prevent a "medical and moral disaster" for the NHS, the lockdown would begin on 5 November when non-essential shops and hospitality will close, but, unlike the first lockdown, schools, colleges and universities will stay open.[119]

On 23 November, the government published a new enhanced tier system[120] which applied in England following the end of the second lockdown period on 2 December.[121] On 16 December Johnson said that restrictions would be relaxed for five days over the Christmas period.[122] That same day, the Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced that a new COVID-19 strain had been discovered, which was named VUI-202012/01.[123] On 20 December Johnson said that the planned Christmas relaxations had been cancelled for London and South East England and limited to a single day for the rest of England as a result of the discovery of the strain.[124]

Third national lockdown

SAGE advised the government to call a third lockdown on 22 December 2020.[125] In a live broadcast on 4 January 2021, Johnson confirmed that England would enter a lockdown from 5 January. All travel and gatherings are banned, except for essential reasons, such as essential work, food shopping and daily exercise. Inter-household mixing is only permitted for essential exercise. All schools and universities must remain closed, with remote learning. Exams have been cancelled.[126] The restrictions are currently expected to last until mid-February.[127]

Vaccination strategy

It has been argued that the UK has implemented a "vaccination strategy that has been the most aggressive in the West".[128] The government pre-ordered 355 million doses of seven different vaccine candidates, among the most comprehensive for its population size in the world.[129] The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approved the Pfizer‑BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine weeks before the United States and the European Union.[128][129][130] Advice on the prioritization for vaccination is given by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), which has recommended prioritization based on clinical vulnerability and age.[131][132]

Vaccine procurement and deployment are the responsibility of the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for COVID-19 Vaccine Deployment,[133] a position created on 28 November 2020 and assumed by Nadhim Zahawi.[134]

On 8 December 2020, the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, began being rolled out across the UK,[135] at University Hospital Coventry, with Margaret Keenan,[136] originally from Enniskillen, Northern Ireland,[137] the first person in the world to get the approved vaccine.

On 30 December 2020, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was approved for use in the UK, and 530,000 doses became available the following week.[138] The first person to get the vaccine, on 4 January 2021, was kidney disease patient Brian Pinker.[139] The Moderna vaccine was approved on 8 January 2021. By that day, approximately 1.5 million people in the UK had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. The government expects the UK to receive 17 million doses of the Moderna vaccine by spring.[140]

On 5 February 2021, the government said it was aiming to offer a vaccine to everyone over the age of 50 by May.[141]

Financial response

Following the a lockdown being announced by the government after the COVID-19 virus reached the country, a financial package designed to help employers and businesses was announced.

Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) is a furlough scheme announced by Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, on 20 March 2020.[142] The scheme was announced on 20 March 2020 as providing grants to employers to pay 80% of a staff wage and employment costs each month, up to a total of £2,500 per person per month. The scheme initially ran for three months and was backdated to 1 March.[143] Following a three-week extension of the countrywide lockdown the scheme was extended until the end of June 2020.[144][145] At the end of May, the scheme was extended until the end of October 2020. After a second lockdown in England was announced on 31 October 2020, a further extension was announced until 2 December 2020,[146] this was followed on 5 November 2020 by a lengthy extension until 31 March 2021.[147] A further extension until 30 April 2021 was announced on 17 December 2020.[148]

Initially the scheme was only for those workers who were on their company's payroll on or before 28 February 2020; this was later changed to 19 March 2020 (i.e. the day before the scheme was announced), making 200,000 additional workers eligible.[149] On the first day of operation 140,000 companies applied to use the scheme.[150][151]

The cost has been estimated at £14 billion a month to run.[152] The decision to extend the job retention scheme was made to avoid or defer mass redundancies, company bankruptcies and potential unemployment levels not seen since the 1930s.[153]

The original scheme closed to new entrants from 30 June 2020 and as claims were made for staff at the end of a three-week period, the last date an employee could be furloughed for the first time was 10 June 2020.[154][155][156][157] As of 27 May 2020, 8.4 million employees had been furloughed under the scheme.[158] With the extension announced on 31 October, the scheme reopened to new entrants and the claim period was reduced to seven days.[146] As of 18 October 2020 the scheme had cost £41.4 billion.[159]

Since July 2020 the scheme has provided more flexibility with employees able to return to part-time work without affecting eligibility. However, employers must cover all wages and employment costs for the hours worked. In addition, since August 2020, National Insurance and pension contributions must be paid by employers. Employer contributions rose to include 10% of wages throughout September 2020 and 20% throughout October 2020 before returning to that of August from November 2020.

By 15 August 80,433 firms had returned £215,756,121 that had been claimed under the scheme. Other companies had claimed smaller amounts of grant cash on the next instalment to compensate for any over payment. HMRC officials believed that £3.5 billion may have been paid out in error or to fraudsters. Games Workshop, Bunzl, The Spectator magazine, Redrow, Barratt Developments and Taylor Wimpey were among the companies who returned all the furlough money they had claimed.[160]

Job Retention Bonus

At the end of July businesses were incentivised to keep on any employee brought back from furlough, by the government promising to pay businesses £1000 for every person they brought back and still had employed on 31 January 2021 as part of the Job Retention Bonus.[161] Several companies stated that they would not be partaking in the scheme.[162]

With the extension of the CJRS this grant will no longer be paid in February 2021.[147]

Job Support Scheme

On 24 September the government announced a second scheme to protect jobs called the Job Support Scheme.[163][164] This scheme was originally due to commence on 1 November 2020 after the CJRS was withdrawn at the end of October 2020. However after subsequent extensions to the CJRS, its implementation has been delayed.[147]

The scheme tops up the wages of employees who have had their hours reduced or where their employer has been legally required to close.

The scheme would be open for six months and eligibility would be reviewed after three months. Initially employees must have worked at least 20% of their contractual hours. For hours not worked two thirds are subsidised with the employer paying 5% and the government paying a further 61.67% up to a limit of £1,541.75 per month.

For businesses legally required to close the government would subsidise 66.67% of employees wages up to a limit of £2,083.33 per month.

Self Employment Income Support Scheme

In March the Self Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) was announced.[165] The scheme paid a grant worth 80% of self employed profits up to £2,500 each month, on companies who's trading profit was less than £50,000 in the 2018-19 financial year or an average less than £50,000 over the last three financial tax years for those who suffered a loss of income. Her Majesty's Revenue & Customs (HMRC) were tasked with contacting those who were eligible and the grant was taxable. The government also had announced a six-month delay on tax payments. Self employed workers who pay themselves a salary and dividends are not covered by the scheme and instead had to apply for the job retention scheme.[166] The scheme went live on 13 May.[167] The scheme went live ahead of schedule and people were invited to claim on a specific date between 13 and 18 May based on their Unique Tax Reference number. Claimants would receive their money by 25 May or within six days of a completed claim.[168] By 15 May, more than 1 million self employed people had applied to the scheme.[169] At the end of May a second grant of up to £6,570 that would be paid in August was announced.[170] Alongside the Job Support Scheme it was announced that two further grants would be available to cover the six-month period from 1 November 2020 to 30 April 2021.[171] The first of these will cover a three-month period and cover 80% of wages capped at £7,500.[172]

Business grants and loans

The government announced Retail, Hospitality and Leisure Grant Fund (RHLGF) and changes to the Small Business Grant Fund (SBGF) on 17 March. The SBGF was changed from £3,000 to £10,000, while the RHLGF offered grants of up to £25,000.[173][174][175] £12.33 billion in funding was committed to the SBGF and the RHLGF schemes with another £617 million added at the start of May.[176] RHLGF and SBGF only applied to business in England.[177] The government pledge £3.5 billion in funding for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales to support to businesses.[173]

On 23 March the government announced the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) for small and medium-sized businesses and Covid Corporate Financing Facility for large companies.[178] The government banned banks from seeking personal guarantees on Coronavirus Business Interruption loans under £250,000 following complaints.[179][180] Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CLBILS) was announced on 3 April and later tweaked to include more companies.[180][181] In May the amount a company could borrow on the scheme was raised from £50 million to £200 million. Restrictions were put in place on companies on the scheme including dividends payout and bonuses to members of the board.[182] On 20 April the government announced a scheme worth £1.25 billion to support innovative new companies that could not claim for coronavirus rescue schemes.[183]

The Rugby Football League was the recipient of a £16 million loan in May 2020 to prevent the professional game from collapsing, especially as England were hosts of the next World Cup.[184] In July 2020 the government pledged £1.57 billion for the arts, culture and heritage industries in the UK.[185] At the end of July a £500 million Film and TV Production Restart Scheme was announced with the intention of providing COVID insurance so that production companies could start making programmes again. It was available for any production that started filming before the end of 2020 and would cover them through to June 2021.[186]

The government additionally announced the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS) for small and medium size businesses on 27 April. The scheme offered loans of up to £50,000 and was interest free for the first year before an interest rate of 2.5% a year was applied, with the loan being paid back within ten[lower-alpha 1] years. Businesses who had an existing CBILS loan of up to £50,000 could transfer on to this scheme, but had to do so by 30 November 2020. The scheme launched on 4 May.[187][188] The loan was 100% guaranteed by the government and was designed to be simpler than the CBILS scheme.[189][190] More than 130,000 BBLS applications were received by banks on the first day of operation with more than 69,500 being approved.[191][189] On 12 May almost £15 billion of state aid had been given to businesses.[192]

The government announced a plan called Project Birch to financially support large companies affected by the pandemic.

On 31 October a grant was announced for businesses required to close by law. The grant known as the Local Restrictions Support Grant will be available on a means tested basis:

- For properties with a rateable value of £15k or under, grants to be £1,334 per month, or £667 per two weeks

- For properties with a rateable value of between £15k-£51k grants to be £2,000 per month, or £1,000 per two weeks

- For properties with a rateable value of £51k or over grants to be £3,000 per month, or £1,500 per two weeks[193]

Eat Out to Help Out

Eat Out to Help Out was a British government scheme announced on 8 July 2020[194] to support and create jobs in the hospitality industry. The government subsidised food and soft drinks at participating cafes, pubs and restaurants at 50%, up to £10 per person. The offer was available from 3 to 31 August on Monday to Wednesday each week.[195]

In total, the scheme subsidised £849 million in meals.[196] Some consider the scheme to be a success in boosting the hospitality industry,[197] however others disagree.[198] In terms of the COVID-19 pandemic, a study at the University of Warwick found that the scheme contributed to a rise in COVID-19 infections.[199]

Other schemes

The UK government announced a £750 million package of support for charities across the UK. £370 million of the money was set aside to support small, local charities working with vulnerable people. £60 million of £370 was allocated to charities in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in the following breakdown

On 13 May the government announced that it was underwriting trade credit insurance, to prevent businesses struggling in the pandemic from having no insurance cover.[202][203]

The Guardian reported that after the government had suspended the standard tender process so contracts could to be issued "with extreme urgency", over a billion pounds of state contracts had been awarded under the new fast-track rules. The contracts were to provide food parcels, personal protective equipment (PPE) and assist in operations. The largest contract was handed to Edenred by the Department for Education, it was worth £234 million and was for the replacement of free school meals.[204] Randox Laboratories who have Owen Paterson as a paid consultant were given a £130 million contract to produce testing kits.[205] In addition 16 contracts totalling around £20 million were agreed to provide HIV and malaria drugs, which were thought might be a cure to COVID-19.[206]

Fraud against the schemes

In June 2020, David Clarke, chair of the Fraud Advisory Panel charity and a group of top white collar crime experts wrote a letter to Rishi Sunak MP, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, National Audit Office and others to alert them the risk of fraud against the government tax-payer backed stimulus schemes. They called for publication of the names of companies receiving Bounce Back Loans to enable data matching to prevent, deter and detect fraud.[207][208] In September 2020, it emerged that Government Ministers were warned about the risk of fraud against the financial support schemes by Keith Morgan CEO of the state owned British Business Bank who had serious concerns about the (BBLS) and Future Fund.[209] In December 2020, it was reported that banks and the National Crime Agency also had serious concerns about fraudulent abuse of the Bounce Back Loan Scheme.[210] In January 2021, the NCA reported that three city workers who worked for the same London financial institution had been arrested as part of an investigation into fraudulent Bounce Back Loans totalling £6 million. The NCA said the men were suspected of using their “specialist knowledge” to carry out the fraud. This form of insider fraud was a risk highlighted in the letter sent to the Chancellor in June 2020.[211]

Reaction and criticism

Following the British government's response to the pandemic, reaction has been generated, and as well as this, various aspects of its response have been criticised. Some have argued that the government did not do enough or did not act quickly enough, while others believe the government's actions have been too harsh and draconian.

As the pandemic generated a financial impact, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak was asked to rapidly act to help by the Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell. The acting leader of the Liberal Democrats, Sir Ed Davey, said that people were being unfairly "hung out to dry", with "their dream jobs turning into nightmares" after hundreds of MPs contacted the Chancellor.[212] The Institute for Employment Studies estimated that 100,000 people could not be eligible for any type of government help as they started a new job to too late to be included on the job retention scheme. While UKHospitality informed the Treasury Select Committee that between 350,000 and 500,000 workers in its sector were not eligible.[213][214] Following changes to the scheme at the end of May, the director of the Northern Ireland Retail Consortium said that being asked to pay wages when businesses had not been trading was an added pressure. While the Federation of Small Businesses were surprised that the Chancellor had announced a tapering of the scheme when ending it.[215] Northern Ireland's economy minister Diane Dodds said that changes to the scheme could be very difficult for some sectors uncertain about when they can reopen, particularly in the hospitality and retail sector, whilst finance minister Conor Murphy said that it was too early in the economic recovery.[216]

The government's public health messaging during the pandemic was hailed as "one of the most successful communications in modern political history" by The Telegraph. The chief executive of WPP plc, one of the world's largest advertising companies, said of the "Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives" slogan: "It has been effective because it is simple. It references our most cherished institution, the NHS, and because it calls for solidarity and collective action". However, the slogan began to be called into question later on in the pandemic when it was suggested that it had contributed to the avoidance of some to go into hospitals to treat other conditions, such as cancer.[59]

Criticism

There has been criticism of the government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many have argued that the restrictions should have been more stringent and more timely. Dr Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, told the BBC's Question Time in March 2020 that "we knew in the last week of January that this was coming. The message from China was absolutely clear that a new virus with pandemic potential was hitting cities. ... We knew that 11 weeks ago and then we wasted February when we could have acted."[217][218] Dr Anthony Costello, a former WHO director, made a similar point in April, saying: "We should have introduced the lockdown two or three weeks earlier. ... It is a total mess and we have been wrong every stage of the way." He also said that "they keep talking about flattening the curve which implies they are seeking herd immunity".[219] And David King, the former chief scientific advisor, said: "We didn't manage this until too late and every day's delay has resulted in further deaths."[220]

In May, Sir Lawrence Freedman, writing for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, accused the government of following public opinion instead of leading it when taking the lockdown decision; and of missing the threat to care homes.[221] At Prime Minister's Questions on 13 May, Labour Party leader Keir Starmer accused Boris Johnson of misleading Parliament in relation to care homes.[222][223]

Criticisms from within the government have been largely anonymous. On 20 April, a No. 10 adviser was quoted by The Times saying: "Almost every plan we had was not activated in February. ... It was a massive spider's web of failing." The same article said Boris Johnson did not attend any of the five coronavirus COBR meetings held in January and February.[224] On The Andrew Marr Show, Minister for the Cabinet Office Michael Gove said it was normal for prime ministers to be absent as they are normally chaired by the relevant department head, who then reports to the PM. The Guardian said the meetings are normally chaired by the PM during a time of crisis and later reported that Johnson did attend one meeting "very briefly".[225][226] On 26 September Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak was said to have opposed a second lockdown with the threat of his resignation, due to what he saw as the dire economic impacts it would have and the responsibility he would have to suffer for that.[227][228]

According to an April 2020 survey carried out by YouGov, three million adults went hungry in the first three weeks of lockdown, with 1.5 million going all day without eating.[229][230] Tim Lang, professor of food policy at City University, London, said that "borders are closing, lorries are being slowed down and checked. We only produce 53% of our own food in the UK. It's a failure of the government to plan."[231]

When Johnson announced plans on 10 May to end the lockdown, some experts were even more critical. Anthony Costello warned that Johnson's "plans will lead to the epidemic returning early [and] further preventable deaths",[232] while Devi Sridhar, chair of global public health at the University of Edinburgh, said that lifting the lockdown "will allow Covid-19 to spread through the population unchecked. The result could be a Darwinian culling of the elderly and vulnerable."[233]

Martin Wolf, chief commentator at the Financial Times, wrote that "the UK has made blunder after blunder, with fatal results".[234] Lord Skidelsky, a former Conservative, said that government policy was still to encourage "herd immunity" while pursuing "this goal silently, under a cloud of obfuscation".[235] The Sunday Times said: "No other large European country allowed infections to sky-rocket to such a high level before finally deciding to go into lockdown. Those 20 days of government delay are the single most important reason why the UK has the second highest number of deaths from the coronavirus in the world."[236]

There have been critics of the full lockdown decisions. They have expressed concern that the seriousness of the virus did not justify the imposition on personal freedom that the lockdowns and social distancing policies took. There are many who have argued that the economic and health costs as a result of the lockdown would outweigh the costs caused by the actual virus. A notable voice for this view is former supreme court judge Lord Sumption who has consistently criticised the government's lockdown policy from the start. Much of the opposition to the lockdown measures came from some right wing press outlets and people of a socially libertarian persuasion. They highlighted the virtues of countries which did not go into lockdowns or had a much more lenient general approach to the virus, such as Sweden.[237]

The columnist Peter Hitchens of The Mail on Sunday argued that the full restrictive lockdown policy on 24 March 2020 would have serious negative consequences as a result of restricting civil liberties, locking down a healthy population, and stalling a healthy economy. He argues that the government should have carried on like Sweden because, "the evidence from Stockholm, which has so far pursued a rational, proportionate, limited policy, still suggests that Sweden will emerge from this less damaged by far than we will."[238] Sumption questioned whether the virus should "warrant putting most of the population into house imprisonment, wrecking our economy for an indefinite period, destroying businesses that honest and hard-working people have taken years to build up, saddling future generations with debt?".[239]

Criticism of legal basis

The legality of the lockdown measures has also been questioned. On 10 September 2020, Lord Sumption said that "lockdown and the quarantine rules and most of the other regulations have been made under the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984", not the Coronavirus Act 2020 itself. Sumption further observed that the only language contained in this Act which confers specific powers over an individual's liberty relates to individuals who are believed "on reasonable grounds" to have contracted an infectious agent, and that thus the powers purported by the Johnson government to enforce lockdown measures on the whole population are in fact ultra vires and of vanishing effect on the vast majority. He found the deliberate employment of this Act to enforce a lockdown a "drastic decision" and "profoundly controversial".[240]

On 13 September 2020, Sumption argued that the new coronavirus social distancing policy of rule of six was unenforceable: "You can enforce it if you're sufficiently intrusive–you can put spies on every street, you can have marshals watching through windows but unless you do that people are not going to respect it unless they think it′s a good idea."[241]

Furthermore, businessman and entrepreneur Simon Dolan launched a crowdfunded legal campaign to bring judicial review against the government for acting illegally and disproportionately over the COVID-19 lockdown.[242] On 1 December, it was ruled that the government should not face a judicial review regarding the initial lockdown measures. Dolan is now seeking permission to escalate to the Supreme Court.[243]

Criticism of lockdowns from scientists

Oncologist Karol Sikora has criticised the government's public health response, expressing concerns that policies of lockdown could impact treatment of other conditions, particularly cancer.[244][245] On 21 September, Sikora alongside Carl Heneghan of University of Oxford, Sunetra Gupta and 28 signatories wrote an open letter to top government officials asking for a rethink to the COVID strategy. They argued in favour of a targeted approach to lockdowns, advising that only over-65s and the vulnerable should be shielded.[246][247] Heneghan has also criticised the government's decision to make facemask wearing mandatory, as he believes the science behind wearing them is shaky. He cited a Danish study into facemasks, the conclusions of which have been met with some contention.[248][249]

Accusations of a lack of a competitive procurement process

Early in the pandemic, the government was criticised for the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) available to NHS workers; as such, there was pressure to supply PPE quickly to the NHS.[250] The UK did not take part in an 8 April bid for €1.5bn (£1.3bn) worth of PPE by members of the European Union, or any bids under the EU Joint Procurement Agreement (set up in 2014 following the H1N1 influenza pandemic[251]), as "we are no longer members of the EU".[252] The purpose of the scheme is to allow EU countries to purchase together as a bloc, securing the best prices and allowing quick procurement at a time of shortage. Under the terms of the Brexit withdrawal agreement, the government had the right to take part until 31 December 2020.[251]

Normally, the UK would have published an open call for bids to provide PPE in the Official Journal of the European Union. However, under EU directives, when there is an "extreme urgency" to buy goods or services, the government does not have to open up a contract to competition; it can instead approach companies directly.[253] During the pandemic, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), local NHS bodies and other government agencies have directly approached firms to provide services, bypassing the EU's tendering process – in some cases without a "call for competition", meaning that only one firm was approached.[253]

One of the largest government PPE contracts went to a small pest control firm Crisp Websites Ltd., trading as PestFix. PestFix secured a contract in April with the DHSC for a £32M batch of isolation suits; three months after the contract was signed, suits from PestFix were not released for use in the NHS as they were being stored at an NHS supply chain warehouse awaiting safety assessments.[250] The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) concluded that supplies of PPE had not been specified to the correct standard for use in hospitals when they were bought. One email from a firm working alongside the HSE in June says that there was "'political' pressure" to get the suits through the quality assurance process.[250] The contract is being challenged in the courts by the not-for-profit Good Law Project (founded by Jolyon Maugham QC), which asked why DHSC had agreed to pay 75% upfront when the provider was "wholly unsuited" to deliver such a large and important order,[250] and further discovered that the company had actually been awarded PPE contracts worth £313m.[254]

The National Audit Office noted that £10.5bn of the overall £18bn spent on pandemic-related contracts (58%) was awarded directly to suppliers without competitive tender, with PPE accounting for 80% of contracts.[255] In light of this report, the Good Law Project opened a number of cases against the DHSC, questioning the awarding of PPE contracts more than £250M to Michael Saiger, head of an American jewellery company based in Florida with no experience of supplying PPE,[254] which involved a £21M payment to Gabriel González Andersson, who acted as an intermediary.[256] The contract was offered without any advertisement or competitive tender process.[254]

Allegations of cronyism

The Sunday Times said the government gave £1.5 billion to companies linked to the party.[257] Although the NAO said there was "no evidence" that ministers were "involved in either the award or management of the contracts",[255] companies who had links to government ministers, politicians or health chiefs were put in a 'high priority' channel;[258] this category was 'fast-tracked', and those in it were ten times more likely to win a contract.[255] BBC economics correspondent Andrew Verity said that "contracts are seen to be awarded not on merit or value for money but because of personal connections".[255] Sophie Hill, a British PhD student at Harvard University, created the online map "My Little Crony" to document alleged cronyism, collating reports from openDemocracy and the Byline Times.[259]

Baroness Harding, a Conservative peer and the wife of Conservative MP John Penrose, was appointed to run NHS Test and Trace.[257] Kate Bingham, a family friend of the PM married to Conservative MP and Financial Secretary to the Treasury Jesse Norman, was appointed to oversee the vaccine taskforce.[260] Bingham went to school with Boris Johnson's sister Rachel Johnson.[261] Bingham accepted the position after decades in venture capital, having been hired without a recruitment process.[262] According to leaked documents seen by The Sunday Times, she charged the taxpayer £670,000 for a team of eight full-time boutique consultants from Admiral Associates.[263] In October 2020, Mike Coupe, a friend of Harding's,[264] took a three-month appointment as head of infection testing at NHS Test and Trace.[265] The Good Law Project and the Runnymede Trust launched a legal case which alleged Johnson acted unlawfully in securing these three contracts and chose them because of their connections to the Conservative Party.[264]

Former Conservative party chair Lord Feldman was appointed as an unpaid adviser to Conservative peer Lord Bethell.[266] Feldman was present when Bethell awarded Meller Designs (owned by David Meller, who gave £63,000 to the Conservative Party, mostly when Feldman was chair) £163 million in contracts for PPE on 6 April.[257] Three days later, Conservative MP and former Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Owen Paterson took part in a phone call with Bethell and Randox, who pay Paterson £100,000 a year as a consultant. The Grand National (the biggest sporting event of the Jockey Club; Harding sits on the club's board) is sponsored by Randox, who received £479M in testing contracts, with orders continuing even after it had to recall half a million tests because of safety concerns.[257] George Pascoe-Watson, chair of Portland Communications, was appointed to an unpaid advisory role by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC); he participated in daily strategic discussions chaired by Bethell.[267] He also sent information about government policy to his paying clients before this was made public.[268][269] Conservative peer Lord O'Shaughnessy was paid as an "external adviser" to the DHSC when he was a paid Portland adviser. In May, O'Shaughnessy took part in a call with Bethell and Boston Consulting Group (BCG), a Portland client that got £21M in contracts on the testing system.[257] BCG management consultants were paid up to £6,250 a day to help speed up and reorganise the Test and Trace system.[270]

Ayanda Capital is a Mauritius-based investment firm with no prior public health experience which gained a £252M contract in April to supply face masks. The contract included an order for 50 million high-strength FFP2 medical masks that did not meet NHS standards, as they had elastic ear-loops instead of the required straps tied behind the wearer's head.[254] Ayanda says they adhered to the specifications they were given.[254] The deal was arranged by Andrew Mills, then an adviser to the Board of Trade (a branch of Liz Truss's Department for International Trade (DIT)); his involvement was criticised by the Good Law Project[261] and Keir Starmer, Leader of the Opposition.[254] The DIT said neither it nor the Board of Trade was involved in the deal.[261]

In June the Cabinet Office published details of a March contract with the policy consultancy Public First, which had been running under emergency procedures, to research public opinion about the government's COVID communications. The company is owned by James Frayne (a long-term political associate of Cummings, co-founding the New Frontiers Foundation with him in 2003) and his wife Rachel Wolf, a former adviser to Michael Gove (Minister for the Cabinet Office) who co-wrote the Conservative party manifesto for the 2016 election. They were given £840,000.[271]

Other allegations of cronyism include:

- Faculty, which worked with Dominic Cummings for Vote Leave during the Brexit referendum, was given government contracts since 2018. After Johnson became PM, a former Faculty employee who worked on Vote Leave, Ben Warner, was recruited by Cummings to work alongside him in Downing Street.[261]

- Hanbury Strategy, a policy and lobbying consultancy, has been paid £648,000 under two contracts (one issued under emergency procedures) to research "public attitudes and behaviours" in relation to the pandemic, the other, at a level that did not require a tender, to conduct weekly polling. The company was co-founded by Paul Stephenson, director of communications for Vote Leave and contender to be Downing Street Chief of Staff. In March last year, Hanbury was given responsibility for assessing job applications for Conservative special advisers.[261]

- Globus Limited, which has donated more than £400,000 to the Conservatives since 2016, won a £93.8M government contract for the supply of respirator face masks.[272]

- Gina Coladangelo, a close friend of Matt Hancock with no known health background, was paid £15,000 as a non-executive director of the DHSC on a six-month contract, although there was no public record of the appointment. She accompanied Hancock to confidential meetings with civil servants. She was given a parliamentary pass sponsored by Bethell (Coladangelo does not play a role in Bethell's team.)[273]

- Alex Bourne, a former neighbour and owner of the Cock Inn pub near Hancock's constituency home, gained a contract which involved supplying "tens of millions of vials for NHS Covid-19 tests".[274]

Notes

- duration was extended from six to ten years as part of the Winter Economy Plan

References

- "UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Overarching government strategy to respond to a flu pandemic: analysis of the scientific evidence base". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Pandemic flu". Government of the United Kingdom. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Pegg, David (7 May 2020). "What was Exercise Cygnus and what did it find?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Syal, Rajeev (16 June 2020). "Permanent secretaries 'not aware of any economic planning for a pandemic'". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- The Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020 Archived 3 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine Government of the United Kingdom

- The Statutory Sick Pay (General) (Coronavirus Amendment) Regulations 2020 Government of the United Kingdom

- The Employment and Support Allowance and Universal Credit (Coronavirus Disease) Regulations 2020 Government of the United Kingdom

- Heffer, Greg (19 March 2020). "Coronavirus Bill: Emergency laws to contain spread of COVID-19 published". Sky News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Carmichael, Hannah (19 March 2020). "Jacob Rees-Mogg says Parliament will return after Easter recess". The National. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Business Closure) (England) Regulations 2020 UK Statutory Instruments 2020 No. 327 Table of contents Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 26 March 2020

- The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 UK Statutory Instruments 2020 No. 350 Table of contents Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 26 March 2020

- "The Health Protection (Coronavirus) (Restrictions) (Scotland) Regulations 2020". Government of the United Kingdom.

- "The Health Protection (Coronavirus Restrictions) (Wales) Regulations 2020". Government of the United Kingdom.

- "The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2020" (PDF). Department of Health (Northern Ireland).

- Dearden, Lizzie (15 June 2020). "Police can forcibly remove people without face masks from public transport and fine them £100". The Independent.

- "Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020". Companies House. 26 June 2020.

- "Coronavirus public information campaign launched across the UK". NHS England. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "News and communications". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Boseley, Sarah; Campbell, Denis; Murphy, Simon (6 February 2020). "First British national to contract coronavirus had been in Singapore". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Kobie, Nicole (15 February 2020). "This is how the UK is strengthening its coronavirus defences". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Department of Health and Social Care, Emergency and Health Protection Directorate, Coronavirus: action plan: A guide to what you can expect across the UK Archived 4 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, published 3 March. Retrieved 7 March 2020

- "Number of coronavirus (COVID-19) cases and risk in the UK". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Russell, Peter (3 February 2020). "New Coronavirus: UK Public Health Campaign Launched". Medscape. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19)". nhs.uk. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Rapson, Jasmine. "NHS collecting coronavirus data from 111 calls". Health Service Journal. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "COVID-19: guidance for staff in the transport sector". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Britain must become the superman of global free trade", The Spectator, 3 February 2020.

- Robert Peston, 'How the government could have done more earlier to protect against Covid-19', ITV News, 19 April 2020.

- Peston, Robert [@Peston] (8 March 2020). "Response from senior government source is "the Italians did several of the populist - non-science based - measures that aren't any use. They're who not to follow"" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "UK is 'following the science' in not banning mass gatherings – health chief". Shropshire Star. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Booth, William (15 March 2020). "U.K. resists coronavirus lockdowns, goes its own way on response". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "The U.K. is aiming for deliberate 'herd immunity'". Fortune. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "60% of UK population need to get coronavirus so country can build 'herd immunity', chief scientist says". The Independent. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Mueller, Benjamin (13 March 2020). "As Europe Shuts Down, Britain Takes a Different, and Contentious, Approach". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Boyle, Christina (19 March 2020). "On coronavirus containment, Britain's Johnson is less restrictive than other European leaders". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "What is herd immunity and is it an option for dealing with the UK coronavirus pandemic?". The Independent. 23 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Wickham, Alex; Nardelli, Alberto; Baker, Katie J.M.; Holmes, Richard. "Even The US Is Doing More Coronavirus Tests Than The UK. Here Are The Reasons Why". BuzzFeed News.

- 'Boris Johnson's coronavirus adviser calls for a way out of lockdown – Britain may still need to adopt herd immunity', The Times, 4 April 2020.

- Alwan, Nisreen A; Bhopal, Raj; Burgess, Rochelle A; Colburn, Tim; Cuevas, Luis E; Smith, George Davey; Egger, Matthias; Eldridge, Sandra; Gallo, Valentina; Gilthorpe, Mark S; Greenhalgh, Trish (17 March 2020). "Evidence informing the UK's COVID-19 public health response must be transparent". The Lancet. 395 (10229): 1036–1037. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30667-x. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7270644. PMID 32197104.

- "Coronavirus could spread 'significantly' – PM". BBC News. 2 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- BBC News Special – Coronavirus: Everything You Need to Know, 2 March 2020, archived from the original on 3 March 2020, retrieved 3 March 2020

- Discombe, Matt (3 March 2020). "National incident over coronavirus allows NHSE to command local resources". Health Service Journal. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Warnick, Mark S.; Sr, Louis N. Molino (2020). Emergency Incident Management Systems: Fundamentals and Applications (Second ed.). Wiley. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-119-26711-9.

- Campbell, Denis; Siddique, Haroon; Weaver, Matthew (3 March 2020). "Explained: UK's coronavirus action plan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Razai, Mohammad S.; Doerholt, Katja; Ladhani, Shamez; Oakeshott, Pippa (6 March 2020). "Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19): a guide for UK GPs". BMJ. 368: m800. doi:10.1136/bmj.m800. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32144127. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Ragoonath, Reshma (7 March 2020). "Public Health England joins Cayman in coronavirus response efforts". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "Government Statement on COVID-19 – 141/2020". Government of Gibraltar. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "PM delivering first daily coronavirus update". BBC News. 16 March 2020.

- O'Hare, Paul (April 2020). "Coronavirus: From one positive case to lockdown". BBC News.

- Rose, Beth (28 April 2020). "Legal move on no sign language at daily briefings". BBC News.

- "'People are dying because of this': Calls for UK Gov to follow Scotland with sign language interpreter at Covid-19 briefing".

- "Coronavirus: Emergency cash to help businesses, and operations delayed". BBC News. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "COVID-19: government announces moving out of contain phase and into delay". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020.

- "High consequence infectious diseases (HCID); Guidance and information about high consequence infectious diseases and their management in England". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Press Association Reporters. "Coronavirus: Timeline of key events since UK was put into lockdown six months ago". The Independent. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Mitha, Sam (2020). "U.K. COVID-19 Diary: Policy and Impacts". National Tax Journal. 73 (3): 852. doi:10.17310/ntj.2020.3.10.

- "Prime Minister's statement on coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020". gov.uk.

- Hope, Christopher; Dixon, Hayley (1 May 2020). "The story behind 'Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives' - the slogan that was 'too successful'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "Government launches new coronavirus advert with stay at home or 'people will die' message". ITV News. 2 April 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "Broadshare And Rescript: What Are The UK's Coronavirus Military Operations?". Forces News. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (24 March 2020). "Coronavirus: Mobile networks send 'stay at home' text". BBC News. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Waterson, Jim (23 March 2020). "Government ignored advice to set up UK emergency alert system". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Sweney, Mark (24 March 2020). "UK mobile firms asked to alert Britons to heed coronavirus lockdown". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "PM Boris Johnson tests positive for coronavirus". BBC News. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Boris Johnson in hospital over virus symptoms". BBC News. 6 April 2020.

- "Statement from Downing Street: 6 April 2020". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Boris Johnson urged to clarify message on wearing face masks in shops". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- 'Cabinet ministers admit there is no lockdown exit plan as they wait for Boris Johnson's return', The Daily Telegraph, 16 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Labour calls for lockdown exit strategy this week". BBC News. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Bunnik, Bram A. D. van; et al. (8 May 2020). "Segmentation and shielding of the most vulnerable members of the population as elements of an exit strategy from COVID-19 lockdown". MedRxiv: 2020.05.04.20090597. doi:10.1101/2020.05.04.20090597. S2CID 218939156 – via medrxiv.org.

- "Coronavirus: 'Segment and shield' way to lift UK lockdown now". BBC News. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Is it time to free the healthy from restrictions?". BBC News. 7 May 2020.

- "'Modest' changes announced to lockdown in Wales". BBC News. 8 May 2020.

- "'Catastrophic mistake' to change lockdown message". BBC News. 7 May 2020.

- "UK 'should not expect big changes' to lockdown". BBC News. 8 May 2020.

- "First Minister lifts exercise rule in Scotland's lockdown". The Scotsman. 10 May 2020.

- Lee, Jeremy; Spainer, Gideon (11 May 2020). "'Single-minded and unavoidable': how the government honed 'Stay home' message". Campaign Live. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Brewis, Harriet (9 May 2020). "Boris Johnson to replace 'stay home' message with 'stay alert' as he delivers lockdown 'road map' address to nation". Evening Standard. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Boseley, Sarah (9 September 2020). "'Hands. Face. Space': UK government to relaunch Covid-19 slogan". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "PM address to the nation on coronavirus: 10 May 2020". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Boris Johnson's lockdown release condemned as divisive, confusing and vague". The Guardian. 10 May 2020.

- "The government's "Stay Alert" slogan is working too hard". New Statesman. 11 May 2020.

- "UK ministers asked not to use 'stay alert' slogan in Scotland". 10 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Minister defends 'stay alert' advice amid backlash". BBC News. 10 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Stewart, Heather; Carroll, Rory; Brooks, Libby (12 May 2020). "Northern Ireland joins in rejection of Boris Johnson's 'stay alert' slogan". The Guardian.

- Beresford, Jack. "Northern Ireland joins Wales and Scotland in rejecting UK government's new 'stay alert' COVID-19 slogan". The Irish Post.

- Williams, James. "Coronavirus: Wales' stay home advice 'has not changed'". BBC News. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales to stick with 'Stay home' message rather then new slogan". ITV News.

- "Coronavirus: Leaders unite against PM's 'stay alert' slogan". Sky News. 10 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Denis Campbell Matthew Weaver and Ian Sample (11 May 2020). "Top experts not asked to approve 'stay alert' coronavirus message". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "'If we don't stay home now, more people will die' Nicola Sturgeon refuses to adopt 'vague and imprecise' Stay Alert slogan". The Herald. Glasgow. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Our plan to rebuild: The UK Government's COVID-19 recovery strategy". Government of the United Kingdom. May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Staying alert and safe (Social distancing)". Government of the United Kingdom. 11 May 2020.

- "Do not drive from England to Wales to exercise". BBC News. 11 May 2020.

- "Non-essential trips to Scotland 'could break law'". BBC News. 11 May 2020.

- "Nicola Sturgeon pleads with media not to confuse England with whole of UK". The National (Scotland). 11 May 2020.

- "Sturgeon: Stay at home message remains in Scotland". BBC News. 10 May 2020.

- Williams, James (17 May 2020). "Starmer calls for 'four-nation' approach to virus". BBC News.

- "Ignoring the North will 'fracture national unity'". BBC News. 17 May 2020.

- Burnham, Andy (16 May 2020). "Are we all in this together? It doesn't look like it from the regions".

- "PM accepts 'frustration' over lockdown rules". BBC News. 17 May 2020.

- McCormack, Jayne (12 May 2020). "NI five-step plan for easing lockdown published". BBC News.

- "CORONAVIRUS EXECUTIVE APPROACH TO DECISION-MAKING" (PDF). Northern Ireland Executive. 12 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus: First moves to ease NI lockdown can start next week". BBC News. 14 May 2020.

- Ng, Kate (15 May 2020). "Wales publishes lockdown exit plan using 'traffic light system'". The Independent.

- McGuinness, Alan (15 May 2020). "Coronavirus: Wales to set out 'first cautious steps' to relax COVID-19 lockdown". Sky News.

- "Cross-party group urges chancellor to consider four-day week for UK". Reuters. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Visiting people at home banned in parts of northern England". BBC News.

- "Covid-19 news: Rising cases in England delay easing of restrictions". New Scientist.

- "Coronavirus: What are social distancing and self-isolation rules?". BBC News. BBC. 8 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Coronavirus: New virus measures 'not a second lockdown'". BBC News. BBC. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Cecil, Nicholas; Prynn, Jonathan (14 August 2020). "Rishi Sunak urges Londoners to return to offices, cafes and restaurants in bid to revive economy". Evening Standard. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Rayner, Gordon; Tominey, Camilla; Hymas, Charles (27 August 2020). "'Go back to work or risk losing your job': Major drive launched to get people returning to the office". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Coronavirus: gatherings of more than six to be banned in England". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Johnson gambles by splitting from his scientists". Financial Times. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Covid rules: How much of the UK is now under some sort of lockdown?". BBC News. UK. 1 October 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.