Social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States has had far-reaching consequences in the country that go beyond the spread of the disease itself and efforts to quarantine it, including political, cultural, and social implications.

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Lockdowns

To encourage residents to remain in their homes in order to help suppress the spread of Covid 19, most U.S. states (either state-wide or phased in on a county-by-county basis) began to impose "stay-at-home orders" from mid-March onward. These orders typically restricted any public "gatherings" and mandated the closure of entertainment and recreation venues (including bars, casinos, fitness facilities, theaters), dine-in restaurants (although take-out and delivery service could still be offered), and other "non-essential" retail businesses. Certain types of businesses were allowed to remain open (subject to social distancing guidelines), including food stores (such as grocery stores), pharmacies, financial institutions, critical infrastructure, and mass media. In some states, hotels were also ordered to close.[1][2] Several states also set up police checkpoints at their borders.[3]

These orders encouraged residents to stay home as much as possible unless they are conducting an essential business (such as grocery shopping or medical care for themselves or family members), recreational exercise, or a job that cannot be performed via telecommuting.[1] The state of New York mandated that non-essential employees of any business work from home.[1]

By April 2, about 90% of the U.S. population was under some sort of restriction.[4] After implementing social distancing and stay-at-home orders, many states were able to sustain an effective transmission rate ("Rt") of less than one.[5]

Reopening

On March 24, Donald Trump expressed a target of lifting restrictions "if it's good" by April 12, the Easter holiday, for "packed churches all over our country".[6] However, a survey of prominent economists by the University of Chicago indicated that abandoning an economic lock-down prematurely would do more economic damage than maintaining it.[7] The New York Times said, "There is, however, a widespread consensus among economists and public health experts that lifting the restrictions would impose huge costs in additional lives lost to the virus—and deliver little lasting benefit to the economy."[8] On March 29, Trump extended the federal physical distancing recommendations until the end of April.[9]

Ohio Governor Mike DeWine says employers must redesign workplaces to keep workers six feet apart, or let them work from home.[10] Connecticut requires employers who are open to keep workers six feet apart, deliver products to customers at curbside or by delivery when possible, protect workers with barriers such as Plexiglas, prohibit sharing equipment or desks and if possible have employees eat and take breaks alone in their cars or at their workstations.[11] Commutes by mass transit, where it is not possible to stay six feet apart, may need to be replaced by cars or dispersed workplaces, including homes.[12] If colleges reopen in person, many will lack large enough classrooms to keep students six feet apart, but if they stay online and lose in-person interactions, students may transfer to less expensive online specialist colleges.[13]

.jpg.webp)

In late April 2020, pressure increased on states to remove economic and personal restrictions. On April 19 the Trump administration released a three-phase advisory plan for states to follow, called "Opening Up America Again".[15] Protests calling for an end to restrictions were held in more than a dozen states.[16] Governors in several states took steps to re-open some businesses the last week of April,[17] even though they did not meet the benchmarks set out in the federal guidelines.[18] Trump alternately encouraged[19] and discouraged the reopening actions.[20] After several meat processing plants were temporarily closed due to coronavirus cases among plant workers, President Trump used the Defense Production Act to order that open plants remain open, and that closed plants re-open with healthy workers.[21]

The CDC prepared detailed guidelines for businesses, public transit, restaurants, religious entities, schools, and other public places who may wish to reopen. In early May, the guidelines were edited down, however the original seven pages were provided to the Associated Press.[22] Six flow charts were ultimately published on May 15,[23] and a 60-page set of guidelines was released without comment on May 20, weeks after many states had already emerged from lockdowns.[24]

On June 8, 2020, The New York Times published results of its survey in which 511 epidemiologists were asked "when they expect to resume 20 activities of daily life". Slightly over half the doctors surveyed responding that they expected to stop "routinely wearing a face covering" in one year or more.[25]

A 69-page document marked "For Internal Use Only" obtained by The New York Times classified the reopening of districts, universities, and individual schools as high risk. The document surfaced after experts warned of high risk in reopening schools. It is not yet clear whether the document has been reviewed by President Trump or not.[26]

Educational impact

As of April 10, 2020, most American public and private schools—at least 124,000—had closed nationwide, affecting at least 55.1 million students.[27] By April 22, school buildings had been ordered or recommended to be closed for the remainder of the academic year in 39 states, three territories, and the District of Columbia.[27] As schools shift education to online learning, there are concerns about student access to necessary technology, absenteeism, and accommodations for special needs students.[28] School systems also looked to adjust grading scales and graduation requirements to mitigate the disruption caused by the unprecedented closures.[29]

To ensure poor students continued to receive lunches while schools were closed, many states and school districts arranged for "grab-and-go" lunch bags or used school bus routes to deliver meals to children.[30] To provide legal authority for such efforts, the U.S. Department of Agriculture waived several school lunch program requirements.[31]

Many higher educational institutions canceled classes and closed dormitories in response to the outbreak, including all members of the Ivy League,[32] and many other public and private universities across the country.[33] Many universities also expanded the use of pass/fail grading for the Spring 2020 semester.[34]

Due to the disruption to the academic year caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Department of Education approved a waiver process, allowing states to opt-out of standardized testing required under the Every Student Succeeds Act.[35] In addition, the College Board eliminated traditional face-to-face Advanced Placement exams in favor of an online exam that can be taken at home.[36] The College Board also cancelled SAT testing in March and May in response to the pandemic.[37] Similarly, April ACT exams were rescheduled for June 2020.[38]

The Department of Education also authorized limited student loan relief, allowing borrowers to suspend payments for at least two months without accruing interest.[35]

In July 2020, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced that she intended to have all American schools open for in-person classes for the 2020-21 school year.[39]

There are broader effects of school closures beyond the immediate crisis. For instance, family choice around in school education is starkly contrasted across race. As of the beginning of the school year in New York City, with 1.1 million school children, 84% of white public-school parents say their child will attend school in-person if possible, compared to 63% of Latinx parents and just 34% of Black parents.[40] Caregivers with greater money, mobility, and access are increasingly withdrawing from, rather than investing in, the “commons” of school and public supports. Many white high-income families are withdrawing from public education, forming private-pay pods ($30,000 per year) or moving. Other families are withdrawing from public education and placing children in religious school ($8,000+ per year).[41]

Many caregivers have left the workforce, facing no other options amid the breakdown of public safety nets.[42] Amid the health risks of offering school; the risks of isolation, disconnection, and educational regression of school disruption; this risk of inequitable access is also critical. Parental choices across race and income pose risk of increased segregation, disparate outcomes, growing inequity, and future public disinvestment in a longer-term post-COVID landscape.[43]

One significant outbreak during the Fall 2020 semester occurred at the State University of New York at Oneonta. Residence halls reopened on August 17, and within two months there were over 700 coronavirus cases among the student body, as a result of which the university president resigned.[44]

Public transportation

.jpg.webp)

Several of the largest mass transit operators in the U.S. have reduced service in response to lower demand caused by work from home policies and self-quarantines. The loss of fares and sales tax, a common source of operating revenue, is predicted to cause long-term effects on transit expansion and maintenance.[45] The American Public Transportation Association issued a request for $13 billion in emergency funding from the federal government to cover lost revenue and other expenses incurred by the pandemic.[46] In mid-April it was reported that demand for transit service was down by an average of 75 percent nationwide, with figures of 85% in San Francisco and 60% in Philadelphia.[47] Many localities reported an increase in bicycling as residents sought socially distant means of getting around.[48]

Prisons

This pandemic has even put tremendous pressure on the current correctional system by adding the responsibility of trying to keep fellow staff and inmates from not spreading Covid 19. As the virus began to spread throughout multiple regions in the U.S it affected correction facilities as well such as inside the prisons. Some states with the help of local jurisdictions began to release prisoners who were considered vulnerable to the virus.[49] The most at risk inmates cost prisons across the country a lot of money due to Covid 19 most were the elderly inmates with preexisting conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and asthma .[49]

To reduce transmission, the Federal Bureau of Prisons started a near-lockdown for all prisoners on April 1, for at least 14 days.[50] Part of this push has involved a call to reduce prison population size.[51] So far prisons are having trouble with crowding and lack of sanitation measures contribute to the risk of contracting diseases in prisons and jails.[52] As a result, of the quality of treatment of prisoners and employees have been affected for the worse. There have been protests around many prisons in different countries due to the frustration of contracting COVID-19 due to conditions in the prisons.[52]

So far there have been multiple Covid 19 outbreaks. One incident was in Bledsoe Correctional Complex in Pikeville, Tennessee. Most of the prisoners who were tested were asymptomatic, and the facility stated it has taken more steps to prevent the outbreak from growing.[53] The main cause of the outbreak of Bledsoe Correctional Complex was that the people working in prisons brought the virus into the prisons affecting 500 prisoners, This is a main concern the correction system is facing all throughout the country.[53]

Immigration detention

More than 38,000 people were detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) at the time of the outbreak of COVID-19 in the United States.[54] ICE's response to the outbreak in detention facilities has been widely characterized as substandard and dangerous.[55] Detained people have reported that they are being forced into unsafe, unsanitary, and harmful conditions.[56] Serious irregularities in ICE's testing data have been reported,[57] while ICE has blocked coronavirus testing information at its facilities from being released to the public.[58] The American Civil Liberties Union referred to the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. immigration detention as "an unquestionable public health disaster".[57]

Xenophobia and racism

There have been incidents of xenophobia and racism against Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans.[60][61][62] The U.S. Federal Protective Service and the FBI's New York office have reported that members of white supremacist groups are encouraging one another, if they contract the virus, to spread it to Jews, "nonwhite" people, and police officers through personal interactions and bodily fluids like saliva.[63][64]

Racial disparities

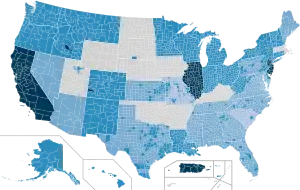

.jpg.webp)

ProPublica conducted an analysis of the racial composition of COVID-19 cases in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, dating through the morning of April 3. They noted that African Americans comprised nearly half the county's cases and 22 of its 27 deaths.[65]

Similar trends have been seen in regions with sizable African American populations, especially in Deep South states such as Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana (which reported on April 6 that 70% of its reported deaths had involved African Americans); in Michigan (33% of cases and 41% of deaths as of April 6); in the city of Richmond, Virginia (48% of the city population, 62% of cases, and 100% of its eight deaths as of April 15)[66] and the city of Chicago, Illinois (1,824 of its 4,680 confirmed cases and 72% of deaths as of April 5).[67][68]

It has been acknowledged that African Americans were more likely to have poor living conditions (including dense urban environments and poverty), employment instability, chronic comorbidities influenced by these conditions, and little to no health insurance coverage—factors which can all exacerbate its impact.[69][70][71] It is also noted that Black Americans are in many states more likely to be "essential workers", people working in jobs that can't work from home during stay-at-home orders. Which puts them at higher exposure to the virus.[71]

The CDC has not yet released national data on coronavirus cases based on race; following calls by Democratic lawmakers and the Congressional Black Caucus, the CDC told The Hill it planned to release data on racial composition of cases.[72][73]

Additionally, the Navajo Nation had the highest rate of infection in the United States, surpassing New York state late May.[74]

On July 20, the Strike for Black Lives was held, with organizers citing racial disparities during the pandemic as a cause of the strike.[75]

In Houston, as well as elsewhere in Texas, Hispanic Americans have been heavily impacted by COVID-19.[76] This is in part because a lot of them are in essential work, much like Black Americans, and live in traditionally multi-generational households, language barriers, and them having low percentage health insurance compared to other ethnicites in the U.S.[77] Additionally, a sizable amount of Hispanics are undocumented immigrants and fear for their immigration status, especially under the Trump presidency which promises hardline immigration laws make it harder for them to seek medical care.[78]

Additionally, Filipino Americans have been impacted perhaps by COVID-19 more than any ethnic community in the United States, in part because of a high percentage of healthcare workers, as many Filipino-Americans are nurses in critical care and emergency rooms, also they have a higher percentage of essential workers than Blacks and Hispanics.[79][80][81]

Aside from these direct health inequities, broader social inequities are a growing effect of the COVID crisis. For instance, amid school closures families are grappling with layered risks of virus risk, income loss, grief, food insecurity, unhealthy environments, learning delay, isolation, lack of information, and more - crumbling or absent public systems risk a new white flight and entrenched segregation for years to come.[41]

Event cancellations

Technology conferences such as Apple Inc.'s Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC),[82] E3 2020,[83] Facebook F8, Google I/O and Cloud Next,[84] and Microsoft's MVP Summit[85][86] have been either canceled or have been replaced with internet streaming events.

On February 21, Verizon pulled out of an RSA conference, along with AT&T and IBM.[87] On February 29, the American Physical Society cancelled its annual March Meeting, scheduled for March 2–6 in Denver, Colorado, even though many of the more than 11,000 physicist participants had already arrived and participated in the day's pre-conference events.[88] On March 6, the annual South by Southwest (SXSW) conference in Austin, Texas, was cancelled after the city government declared a "local disaster" and ordered conferences to shut down for the first time in 34 years. The cancellation was not covered by insurance.[90] In 2019, 73,716 people attended the conferences and festivals, directly spending $200 million and ultimately boosting the local economy by $356 million, or four percent of the annual revenue of the region's hospitality and tourism economic sectors.[91]

On March 12, a Post Malone concert at Denver's Pepsi Center proceeded as scheduled, drawing a sellout-crowd of 20,000, likely the largest enclosed gathering in the U.S. before widespread lockdowns.[92]

After the cancellations of the Ultra Music Festival in Miami and SXSW in Austin, speculation began to grow about the Coachella festival set to begin on April 10 in the desert in Indio, California. The annual festival, which has attracted some 125,000 people over two consecutive weekends, is insured only in the event of a force majeure cancellation such as one ordered by local or state government officials. Estimates on an insurance payout range from $150 million to $200 million.

As the year comes to an end, live music event's continue to be canceled. Coronavirus cases continue to rise, thus, the music industry is in a crisis. In its recent third-quarter earnings report for 2020, Live Nation Entertainment reported a 95% revenue drop industry-wide.[95] According to a report by research and trade publication named Pollstar, the music industry can lose up to $9 billion in 2020. Working musicians are struggling to get by, thus, venues continue to close. Before working musicians could get by with selling records, however, with streaming services today, working musicians rely heavily on touring for income.

Ticketmaster is experimenting with viable options when reopening live music events such as requiring proof of a Coronavirus vaccine or a negative Coronavirus test. The framework plan could work through the Ticketmaster digital app and third-party health companies and customers would be required to get tested approximately 24 to 72 hours before a concert.[96] When presenting a digital ticket, both the confirmation of ticket purchase and proof of a negative test result will be shown before entering the event. No medical records are said to be stored from each participant but serve as a method of proof that the individual is safe to attend the event.

In Germany, researchers have conducted a study on indoor concert events to test the safety risks of virus transmission. Analysis of an indoor concert staged by scientists in August suggests that the impact of such events on the spread of the coronavirus is “low to very low” as long as organizers ensure adequate ventilation, strict hygiene protocols, and limited capacity, according to the German researchers who conducted the study.[97] Although the study by German Researches was received with great optimism by event organizers, there is much more studying that needs to be conducted before giving the green light to opening concert venues

Media

Publishing

The scale of the COVID-19 outbreak has prompted several major publishers to temporarily disable their paywalls on related articles, including Bloomberg News, The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Seattle Times.[98][99] Many local newspapers were already severely struggling before the crisis.[99] Several alt weekly newspapers in affected metropolitan areas, including The Stranger in Seattle and Austin Chronicle, have announced layoffs and funding drives due to lost revenue. Advertisements concerning public events and venues accounted for a majority of revenue for alt-weekly newspapers, which was disrupted by the cancellation of large public gatherings.[99][100] Online advertisements also dropped to avoid running ads next to coronavirus coverage.[101]

Film

Most U.S. cinema chains, where allowed to continue operating, reduced the seating capacity of each show time by half to minimize the risk of spreading the virus between patrons.[102] Audience limits, as well as mandatory and voluntary closure of cinemas in some areas, led to the lowest total North American box office sales since October 1998.[103] On March 16, numerous theater chains temporarily closed their locations nationwide.[104] A number of Hollywood film companies have suspended production and delayed the release of some films.[105][106]

Television

Many television programs began to suspend production in mid-March due to the pandemic.[107][108] News programs and most talk shows have largely remained on-air, but with changes to their production to incorporate coverage of the pandemic, and adhere to CDC guidelines on physical distancing and the encouragement of remote work.[109][110][111] Quarantine and remote work efforts, as well as interest in updates on the pandemic, have resulted in a larger potential audience for television broadcasters—especially for news programs and news channels. Nielsen estimated that by March 11 television usage had increased by 22% week-over-week. It was expected that streaming services would see an increase in usage, while potential economic downturns associated with the pandemic could accelerate the market trend of cord cutting.[112][113][114]

The Hollywood Reporter observed gains in average viewership for some programs between March 9 and April 2, with the top increases including The Blacklist (31.2% gain in average audience since March 9), and 20/20 (30.8%).[115] These effects have also been seen on syndicated programs,[116] and the Big Three networks' daytime soap operas.[117] WarnerMedia reported that HBO Now saw a spike in usage, and the most viewed titles included documentary Ebola: The Doctors' Story and the 2011 film Contagion for their resonance with the pandemic.[118]

Sports

.jpg.webp)

The 2020 BNP Paribas Open tennis tournament at Indian Wells was postponed on March 8, 2020, marking the first major U.S. sports cancellation attributed to the outbreak.[119][120]

In compliance with restrictions on large gatherings, the Columbus Blue Jackets (NHL), Golden State Warriors (NBA), and San Jose Sharks (NHL) announced their intent to play home games behind closed doors, with no spectators and only essential staff present.[121][122][123][124] These proposals were soon rendered moot, when suspension of games for various time periods were announced by almost all professional sports leagues in the United States on March 11 onward, including the National Basketball Association (which had a player announced as having tested positive),[125] National Hockey League,[126] Major League Baseball,[127] Major League Soccer, Major League Rugby,[128] and National Volleyball Association.[129][130]

College athletics competitions were similarly cancelled by schools, conferences and the NCAA—which cancelled all remaining championships for the academic year on March 12. This also resulted in the first-ever cancellation of the NCAA's popular "March Madness" men's basketball tournament (which had been scheduled to begin the following week) in its 81-year history.[125][131][132]

NFL is considering playing with helmets with installed filters.[133]

Health insurance

Millions of Americans lost their health insurance after losing their jobs.[134][135][136][137] The Independent reported that Families USA "found that the spike in uninsured Americans – adding to an estimated 84 million people who are already uninsured or underinsured – is 39 per cent higher than any previous annual increase, including the most recent surge at the height of the recession between 2008 and 2009 when nearly 4 million non-elderly Americans lost insurance."[138]

Religious services

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, many churches, mosques, synagogues and temples have suspended religious services to avoid spreading the disease.[139] Some religious organizations offered radio, television and online services, while others have offered drive-in services.[140] Despite the pandemic, many American religious organizations continue to operate their food pantries. Churches offered bags filled with food and toilet paper rolls for families in need.[141] Many mosques have closed for prayers but continue to run their food banks.[142][143][144]

The National Cathedral of the United States, which belongs to the Episcopal Church, donated more than 5,000 N95 surgical masks to hospitals of Washington D.C., which were in shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic.[145] Other churches, such as the Church of the Highlands, an evangelical Christian megachurch, have offered free COVID-19 tests in their parking lots.[146]

Some state orders against large gatherings, such as in Ohio and New York, specifically exempt religious organizations.[147] Colorado Springs Fellowship Church insists it has a constitutional right to defy a state closure order.[148] Evangelical college Liberty University of Lynchburg, Virginia, moved its classes online but called its 5,000 back to campus despite Governor Ralph Northam's order to close all non-essential businesses.[149] On March 13, 2020, Bishop Elaine JW Stanovsky of the Pacific Northwest Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church issued a statement that would be updated no later than the start of Holy Week, which directed "the local churches of any size and other ministries in the states of Alaska, Idaho, Oregon and Washington to suspend in-person worship and other gatherings of more than 10 people for the next two weeks."[150]

In the state of Kansas, the Democratic governor, Laura Kelly responded to a prime source of spread of the disease by banning religious services attended by more than 10 people.[151] In April, Texas churches were meeting while following social distancing guidelines after Texas Governor Greg Abbott joined more than 30 governors who had already deemed religious services "essential".[152] A federal appeals court ruled that Kentucky churches must be permitted to hold drive-in church services.[153]

Opioid crisis

In April 2020, Politico reported that the federal government's top addiction and mental health experts began to warn that the coronavirus pandemic could derail the progress the country has made addressing the opioid crisis because such efforts have been "sidelined" by the government's response to COVID-19. The director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Nora Volkow, said, "I think we're going to see deaths climb again. We can't afford to focus solely on Covid."[154] In January, the Trump administration announced that opioid overdose deaths in 2018 were down four percent from the previous year. This was the first drop in the statistic in nearly 30 years.[154] According to Portland ABC affiliate station KATU, "The coronavirus has been a crushing blow for the addiction recovery community, specifically, when it comes to social distancing, advocates say."[155]

Foster care

References

- "A Guide to State Coronavirus Lockdowns", The Wall Street Journal, March 21, 2020

- "Illinois, New York, California, Nevada Tighten Restrictions to Fight Coronavirus", The Wall Street Journal, March 20, 2020

- Lazo, Luz; Shaver, Katherine (April 14, 2020). "Covid-19 checkpoints targeting out-of-state residents draw complaints and legal scrutiny". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "About 90% of Americans have been ordered to stay at home. This map shows which cities and states are under lockdown". Business Insider. April 2, 2020.

- Systrom K, Krieger M, O'Rourke R, Stein R, Dellaert F, Lerer A (April 11, 2020). "Rt Covid-19". rt.live. Retrieved April 19, 2020. Based on Bettencourt, Luís M. A.; Ribeiro, Ruy M. (May 14, 2008). "Real Time Bayesian Estimation of the Epidemic Potential of Emerging Infectious Diseases". PLOS ONE. 3 (5): e2185. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2185B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002185. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2366072. PMID 18478118.

- Liptak, Kevin; Vazquez, Maegan; Valencia, Nick; Acosta, Jim (March 25, 2020). "Trump says he wants the country 'opened up and just raring to go by Easter', despite health experts' warnings". CNN. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "IGM Economic Experts Panel-Policy for the COVID-19 Crisis". igmchicago.org. March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Shutdown Spotlights Economic Cost of Saving Lives". The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

- "How 15 Days Became 45: Trump Extends Guidelines To Slow Coronavirus". NPR. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Tobias, Andrew J.; clevel; .com (March 19, 2020). "What can I do if my workplace doesn't seem safe from coronavirus?". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Safe Workplace Rules for Essential Employers". State of Connecticut. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Cutter, Chip (April 27, 2020). "Biggest Hurdle to Bringing People Back to the Office Might Be the Commute". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Harris, Adam (April 24, 2020). "What If Colleges Don't Reopen Until 2021?". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "Trump's first foreign visitor amid pandemic is Poland's nationalist president". CNN. June 24, 2020.

- "President Trump Issues Guidelines for 'Opening Up America Again'". City Beat. April 19, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Jeffrey, Adam (April 20, 2020). "Scenes of protests across the country demanding states reopen the economy amid coronavirus pandemic". CNBC. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Moreno, J. Edward (April 25, 2020). "Several states starting to reopen this weekend". The Hill. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Scheneman, Dan (April 24, 2020). "Too Soon? States Reopen Without Meeting Federal Guidelines". NBC News. My High Plains News. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Fears, Danika (April 17, 2020). "Trump Calls on People to 'LIBERATE' Virus-Stricken States With Democratic Governors". Daily Beast. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Rojas, Rick (April 22, 2020). "Trump Criticizes Georgia Governor for Decision to Reopen State". The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Jiang, Weijia; Quinn, Melissa (April 29, 2020). "Trump invokes Defense Production Act to keep meat processing plants open amid coronavirus crisis". CBS News. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Dearen, Jason; Stobbe, Mike (May 6, 2020). "Trump administration buries detailed CDC advice on reopening". The Associated Press. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas (May 15, 2020). "C.D.C. Issues Reopening Checklists for Schools and Businesses". The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Chuck, Elizabeth (May 20, 2020). "CDC quietly releases detailed plan for reopening America". NBC News. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Sanger-Katz, Margot (June 8, 2020). "When 511 Epidemiologists Expect to Fly, Hug and Do 18 Other Everyday Activities Again". The New York Times. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "As Trump Demanded Schools Reopen, His Experts Warned of 'Highest Risk'". The New York Times. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- "Map: Coronavirus and School Closures". Education Week. Editorial Projects in Education. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Goldstein, Daniel; Popescu, Adam; Hannah-Jones, Nikole (April 6, 2020). "As School Moves Online, Many Students Stay Logged Out". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Sawchuk, Stephen (April 1, 2020). "Grading Students During the Coronavirus Crisis: What's the Right Call?". Education Week. Bethesda, Maryland. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- "Schools Scramble to Feed Students After Coronavirus Closures". U.S. News & World Report. Washington, D.C. Associated Press. March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- "H.R. 6201 Update—USDA Issues Nationwide Child Nutrition Waivers". News. Arlington, Virginia: School Nutrition Association. March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Murray, Conor. "Online classes, travel bans: How the Ivy League is responding to the coronavirus outbreak". thedp.com. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Columbia, Harvard, NYU, and other major US colleges and universities that have switched to remote classes and are telling students to move out of dorms to prevent the spread of the coronavirus". Business Insider. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- Burke, Lilah (March 19, 2020). "#Pass/Fail Nation". Inside Higher Education. Washington, D.C. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Nadworny, Elissa (March 20, 2020). "Education Dept. Makes Changes To Standardized Tests, Student Loans Over Coronavirus". Corona Virus Daily. Washington, D.C.: NPR. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- "AP Updates for Schools Impacted by Coronavirus". AP Central. New York City: The College Board. March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- "SAT Coronavirus Updates". College Board. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- "ACT Reschedules April 2020 International ACT Test Date to June". ACT Newsroom & Blog. March 19, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Blitzer, Ronn (July 12, 2020). "DeVos vows to have schools open in fall: 'Kids have got to get back to school'". Fox News. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Education Trust | Global Strategy Group. "Survey among 804 parents of children in New York State public schools from August 8th to 19th, 2020. Data highlights" (PDF).

- "What Happens When Private Schools Reopen and Public Schools Don't?". Time. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- Harris, Olga Khazan, Adam (September 3, 2020). "What Are Parents Supposed to Do With Their Kids?". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- "As wealthy parents relocate students from public schools in West Harlem, districts are left vulnerable to COVID-19 budget cuts". Columbia Daily Spectator. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- Grayer, Annie; Snyder, Alec (October 16, 2020). "The president of a New York college resigns after more than 700 students test positive for Covid-19". CNN. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Taylor, Kate (March 17, 2020). "No Bus Service. Crowded Trains. Transit Systems Struggle With the Virus". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Lindblom, Mike; Groover, Heidi (March 19, 2020). "Sound Transit, Metro facing big drops in funding as coronavirus downturn takes hold". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Hughes, Trevor (April 14, 2020). "Poor, essential and on the bus: Coronavirus is putting public transportation riders at risk". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- Anderson, L.V. (March 13, 2020). "Coronavirus has caused a bicycling boom in New York City". Grist. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- "US jails begin releasing prisoners amid pandemic". BBC News. March 19, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Prisoners Across U.S. Will Be Confined For 14 Days To Cut Coronavirus Spread". NPR.org.

- ServickSep. 17, Kelly; 2020; Am, 10:15 (September 17, 2020). "Pandemic inspires new push to shrink jails and prisons". Science | AAAS. Retrieved October 22, 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Cheney-Rice, Zak (March 27, 2020). "Coronavirus Fears Spark Prison Strikes, Protests, and Riots Around the World". Intelligencer. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- "COVID-19 outbreak infecting over 500 prisoners may have come from staff: Medical director". ABC News. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- Aleaziz, Hamed (March 31, 2020). "ICE Must Release 10 Chronically Ill Immigrants After A Judge Said They're Not Safe From The Coronavirus While In Custody". BuzzFeed News.

- "US: Suspend Deportations During Pandemic: Forced Returns Risk Further Global Spread of Virus". Human Rights Watch. June 4, 2020.

- Madan, Monique O. (June 4, 2020). "As ICE detainee testifies in federal court about COVID-19, unmasked guard is next to him". The Miami Herald.

- Cho, Eugene (May 22, 2020). "ICE's Lack of Transparency About COVID-19 in Detention Will Cost Lives". ACLU.

- Nelson, Blake (April 23, 2020). "ICE blocks release of coronavirus testing information at jail, N.J. official says". NJ.com.

- Douglas, Erin; Takahashi, Paul (February 6, 2020). "'People just disappeared': Coronavirus fears weighing on Houston's economy". HoustonChronicle.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- Tavernise, Sabrina; Oppel Jr, Richard A. (March 23, 2020). "Spit On, Yelled At, Attacked: Chinese-Americans Fear for Their Safety". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "Fear of coronavirus fuels racist sentiment targeting Asians". Los Angeles Times. February 3, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Officials decry anti-Asian bigotry, misinformation amid coronavirus outbreak". Los Angeles Times. March 3, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "White supremacists encouraging their members to spread coronavirus to cops, Jews, FBI says". ABC News. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Walker, Hunter; Winter, Jana (March 21, 2020). "Federal law enforcement document reveals white supremacists discussed using coronavirus as a bioweapon". Yahoo News. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Early Data Shows African Americans Have Contracted and Died of Coronavirus at an Alarming Rate". ProPublica. April 3, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Rodriguez Espinoza, Alan (April 15, 2020). "African Americans Make Up All of Richmond Coronavirus Deaths". VPM.org. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Coronavirus wreaks havoc in US black communities". BBC News. April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Zanolli, Lauren (April 8, 2020). "Data from US south shows African Americans hit hardest by Covid-19". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Russel, Gordon. "Here's why these 13 Louisiana parishes have some of the highest coronavirus death rates in the U.S." NOLA.com. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Eligon, John (April 7, 2020). "Black Americans Face Alarming Rates of Coronavirus Infection in Some States". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Levenson, Eric. "Why black Americans are at higher risk for coronavirus". CNN. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Swanson, Ian (April 7, 2020). "Black, Latino communities suffering disproportionately from coronavirus, statistics show". TheHill. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Moreno, J. Edward (April 8, 2020). "Congressional Black Caucus calls on CDC to report racial data". TheHill. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Hollie Silverman; Konstantin Toropin; Sara Sidner; Leslie Perrot. "Navajo Nation surpasses New York state for the highest Covid-19 infection rate in the US". CNN. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Schallom, Rachel (July 20, 2020). "8 workers on why they're walking out in today's Strike for Black Lives protest". Fortune. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Moreno, Mayra (August 4, 2020). "All deaths reported Monday from COVID-19 were Hispanic". ABC13 Houston. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Trevizo, Perla (July 30, 2020). ""It cost me everything": Hispanic residents bear brunt of COVID-19 in Texas". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Caldwell, Alicia A. (July 13, 2020). "As Covid-19 Cases Surge, Latino Communities Feel the Brunt". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Coronavirus Is Killing Filipino Americans at Much Higher Rate: Report". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "How COVID-19 has taken a toll on Filipino-American healthcare workers". FOX 5 New York. May 21, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "5 Ways COVID-19 Might Be Affecting Filipino Americans". Psychology Today. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Leswing, Kif (March 13, 2020). "Apple moves WWDC developers conference online due to coronavirus". CNBC. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- Machkovech, Sam (March 11, 2020). "It's official: E3 2020 has been canceled [Updated]". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on March 11, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Gartenberg, Chaim (February 27, 2020). "Facebook cancels F8 developer conference due to coronavirus concerns". The Verge. Archived from the original on March 11, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Foley, Mary Jo. "Microsoft cancels MVP Summit due to COVID-19 coronavirus fears". ZDNet. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Statt, Nick (March 2, 2020). "Google and Microsoft just canceled two conferences ahead of their major ones". The Verge. Archived from the original on March 11, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "Novel Coronavirus Update". RSA Conference. January 26, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Castelvecchi, Davide (March 2, 2020). "Coronavirus fears cancel world's biggest physics meeting". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00609-0. PMID 32203350. S2CID 214627902.

- Curtin, Kevin (March 6, 2020). "SXSW Cancellation Not Covered by Insurance; Communicable diseases, viruses, and pandemics not part of policy". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 7, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Sechler, Bob; Hawkins, Lori; Novak, Shonda (March 7, 2020). "Loss of SXSW a gut punch for some Austin businesses". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Colorado COVID-19 Timeline". ColoradoBiz. 47: 21. June 2020.

- Baker, Alex (November 3, 2020). "As Pandemic Wears on, Working Musicians Are Struggling, Innovating, Adapting".

- Ryan, Patrick (November 12, 2020). "Ticketmaster may require vaccinations, negative COVID-19 tests when concerts return".

- Kwai, Isabella (November 3, 2020). "Coronavirus Study in Germany Offers Hope for Concertgoers".

- Jerde, Sara (March 12, 2020). "Major Publishers Take Down Paywalls for Coronavirus Coverage". Adweek. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- Allsop, Jon (March 13, 2020). "How the coronavirus could hurt the news business". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- Scire, Sarah (March 12, 2020). ""This time is different": In Seattle, social distancing forces The Stranger to make a coronavirus plea". Nieman Foundation for Journalism. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "Pandemic Threatens Local Papers Even As Readers Devour Their Coverage". NPR.org.

- McNary, Dave (March 13, 2020). "Movie Theaters Cut Seating Capacity Over Coronavirus". Variety. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (March 15, 2020). "Weekend Box Office Plunges To 22-Year Low At $55M+, Theater Closings Rise To 100+ Overnight As Coronavirus Fears Grip Nation—Sunday Final". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (March 17, 2020). "Coronavirus Theater Closures in U.S./Canada Hit 3K As Alamo Drafthouse & Others Go Dark: "This News ... Is Devastating"". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Hipes, Patrick (March 16, 2020). "Coronavirus: Movies That Have Halted Or Delayed Production Amid Outbreak". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Here are all the movie releases that have been postponed due to coronavirus". Los Angeles Times. March 17, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Hollywood production has shut down. Why thousands of workers are feeling the pain". Los Angeles Times. March 17, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Maglio, Tony; Nakamura, Reid; Maas, Jennifer; Baysinger, Tim (March 30, 2020). "All the TV Productions Suspended or Delayed Due to Coronavirus Pandemic (Updating)". TheWrap. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Forgey, Quint. "The president's favorite morning show starts social distancing". Politico. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- Steinberg, Brian (March 16, 2020). "From Big Debate to 'Today', Coronavirus Forces Quick Change for TV News". Variety. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- Steinberg, Brian (March 17, 2020). "ABC Will Suspend 'Strahan, Sara & Keke' in Favor of Coronavirus News Show". Variety. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Lee, Edmund; Koblin, John (March 17, 2020). "Glued to TV for Now, but When Programming Thins and Bills Mount ..." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Hersko, Tyler (March 18, 2020). "Analysts Warn TV Viewership Increases Won't Stop Financial Hit from Coronavirus". IndieWire. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Draper, Kevin (March 16, 2020). "When Coronavirus Turns Every Sports Channel into ESPN Classic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- "TV Long View: The Shows With the Biggest Quarantine Viewing Gains". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "'Wheel of Fortune,' 'Dr. Oz' Score Big Ratings Gains During Quarantines". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Ausiello, Michael (March 31, 2020). "Daytime Soaps Surge: B&B, Days, GH and Y&R Experience Significant Ratings Boosts as America Quarantines". TVLine. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Petski, Denise (March 24, 2020). "HBO Now Usage Leaps 40% Amid Coronavirus Crisis; WarnerMedia Posts Viewership Gains With Titles Like 'Ebola' & Contagion'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- Rothenberg, Ben; Clarey, Christopher (March 8, 2020). "Indian Wells Tennis Tournament Canceled Because of Coronavirus Outbreak". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Wolken, Dan. "Opinion: Indian Wells cancellation could be turning point for sports and coronavirus". USA Today. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "San Jose Sharks to play games without fans". Los Angeles Times. March 12, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "NBA Suspends Season Amid Coronavirus Outbreak". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Deb, Sopan; Cacciola, Scott; Stein, Marc (March 11, 2020). "Sports Leagues Bar Fans and Cancel Games Amid Coronavirus Outbreak". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "As leagues and teams begin to shut door on fans because of coronavirus, will NHL follow?". Los Angeles Times. March 11, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- "The Day Sports Shut Down". The Wall Street Journal. March 12, 2020. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "NHL suspends regular season due to coronavirus concerns". Sportsnet. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Toscano, Justin. "MLB delays season indefinitely after CDC announces restrictions amid coronavirus fears". North Jersey.

- "Major League Rugby Cancels 2020 Season & Returns in 2021 – djcoilrugby".

- "CONCACAF, Liga MX take coronavirus measures". ESPN. March 12, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Kimball, Spencer (March 12, 2020). "Major League Soccer suspends season for 30 days amid concern over coronavirus". CNBC. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- "No shining moments: NCAA basketball tournaments are canceled for the first time". Los Angeles Times. March 13, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Coronavirus updates: NCAA cancels championship competition for all winter and spring sports". CBSSports.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "NFL testing N95, surgical mask material on modified face masks in hopes of fighting COVID-19 spread—CBSSports.com".

- "Millions Have Lost Health Insurance in Pandemic-Driven Recession". The New York Times. July 13, 2020.

- "5.4 million Americans have lost their health insurance. What to do if you're one of them". CNBC. July 14, 2020.

- "27 million Americans could lose health insurance as Congress proposes industry 'bailout'". The Independent. May 13, 2020.

- "Up to 43m Americans could lose health insurance amid pandemic, report says". The Guardian. May 20, 2020.

- "Coronavirus: 5.4m Americans lost health insurance during pandemic, report says". The Independent. July 15, 2020.

- "The great shutdown 2020: What churches, mosques and temples are doing to fight the spread of coronavirus". CNN News.

- "Westerville church offering 'drive in' service". WBNS-TV. March 22, 2020. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Dias, Elizabeth (March 15, 2020). "A Sunday Without Church: In Crisis, a Nation Asks, 'What Is Community?'". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "'We see this as our responsibility': Muslims fundraise for Americans impacted by coronavirus". Middle East Eye.

- Griswold, Eliza. "An Imam Leads His Congregation Through the Pandemic". The New Yorker.

The mosque was no longer hosting daily prayer, since disinfecting the carpet four times a day had proved to be an overwhelming amount of work. But it was still giving out food to those who needed it.

- "Muslim communities delivering food, medication to sick and elderly during coronavirus pandemic". pennlive.com. March 20, 2020.

- Gryboski, Michael (March 26, 2020). "National Cathedral donates 5,000 respirator masks to DC hospitals". The Christian Post. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "Amazon Adds Jobs and Megachurch Helps with Covid-19 Testing". Religious Freedom & Business Foundation. March 19, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Murdock, Jason (March 23, 2020). "U.S. CHURCHES HOLD PUBLIC SUNDAY SERVICES DESPITE CORONAVIRUS OUTBREAK: 'THIS IS DANGEROUS'". Newsweek. One of Greater Cincinnati's Largest Churches Continues Services Despite Coronavirus City Beat (Cincinnati), March 24, 2020

- Colorado Springs church says it has Constitutional right to open, defying state health order By Chelsea Brentzel, KRDO, March 24, 2020

- Liberty University welcomes back students despite coronavirus BY MARTY JOHNSON, The Hill, March 24, 2020

- Bloom, Linda (March 13, 2020). "Churches adapting to COVID-19 restrictions". United Methodist News Service. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Kansas Supreme Court says executive order banning religious service of more than 10 people stands, KMBC, April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ProPublica, Kiah Collier, Perla Trevizo and Vianna Davila, The Texas Tribune and (April 2, 2020). "Despite coronavirus risks, some Texas religious groups are worshipping in person—with the governor's blessing". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Ward, Karla (May 2, 2020). "Federal appeals court rules that Beshear must allow Louisville church's drive-in services". Lexington Herald Leader. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- Goldberg, Dan; Ehley, Brianna (April 10, 2020). "Trump officials, health experts worry coronavirus will set back opioid fight". Politico. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- Schreiber, Evan (April 14, 2020). "Report: Health experts worry opioid fight set back by coronavirus". KATU. Retrieved April 15, 2020.