COVID-19 in pregnancy

The effect of COVID-19 infection on pregnancy is not completely known because of the lack of reliable data.[2] If there is increased risk to pregnant women and fetuses, so far it has not been readily detectable.

| COVID-19 in pregnancy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virtual model of coronavirus. | |

| Risk factors | Severe infection |

| Prevention | Covering cough, avoid interacting with sick people, cleaning hands with soap and water or sanitizer |

| Deaths | 2[1] |

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Predictions based on similar infections such as SARS and MERS suggest that pregnant women are at an increased risk of severe infection[3][4] but findings from studies to date show that clinical characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia in pregnant women were similar to those reported from non-pregnant adults.[5][6]

There are no data suggesting an increased risk of miscarriage of pregnancy loss due to COVID-19 and studies with SARS and MERS do not demonstrate a relationship between infection and miscarriage or second trimester loss.[7]

It is unclear yet whether conditions arising during pregnancy including diabetes, cardiac failure, hypercoagulability or hypertension might represent additional risk factors for pregnant women as they do for non-pregnant women.[5]

From the limited data available, vertical transmission during the third trimester probably does not occur, or only occurs very rarely. There is no data yet on early pregnancy.[5]

Research about COVID-19 in pregnancy

Little evidence exists to permit any solid conclusions about the nature of COVID-19 infection in pregnancy.[8]

Effect on pregnant women

In May 2020, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) reported the results from a UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) study of 427 pregnant women and their babies.[9] This study showed that 4.9 pregnant women per 1000 were admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and 1 in 10 of these required intensive care.[10]

The findings of this study support earlier suggestions that pregnant women are not at greater risk of severe illness than non-pregnant women. Similar risk factors also apply: women in the study were more likely to be admitted to hospital if they were older, overweight or obese, or had pre-existing conditions such as diabetes or high blood pressure.[9] Five women died but it is not yet clear whether the virus was the cause of death.[9] Since the majority of women who became severely ill were in their third trimester of pregnancy, the RCOG and RCM emphasised the importance of social distancing for this group.[9] The study also found that 55% of pregnant women admitted to hospital with COVID-19 were from a black or other minority ethnic (BAME) background, which is far higher than the percentage of BAME women in the UK population. Speaking for the RCOG, Dr Christine Ekechi stated that it is of "great concern" that over half of those admitted to hospital were from a BAME background, that there were already "persisting vulnerabilities" for this group, and that the RCOG was updating guidance to lower the threshold to review, admit and consider escalation of care for pregnant women of BAME background.[9] The UK Audit and Research Collaborative in Obstetrics and Gynaecology undertook a UK wide evaluation of women's health care services in response to the acute phase of the pandemic, finding more work was required in the long term for the provision of both maternity and gynaecology oncology services.[11][12]

A case series of 43 women from New York who tested positive for COVID-19 showed similar patterns to non-pregnant adults: 86% had mild disease, 9.3% had severe disease and 4.7% developed critical disease.[13] Another study found the cases of COVID-19 pneumonia in pregnancy were milder and with good recovery.[14]

A study of 9 infected women at the third trimester of pregnancy from Wuhan, China showed that they showed fever (in six of nine patients), muscle pain (in three), sore throat (in two) and malaise (in two). Fetal distress was reported in two. None of the women developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia or died. All of them had live birth pregnancies and no severe neonatal asphyxia was observed. The samples of breast milk, amniotic fluid, cord blood and neonatal throat swab were tested for SARS-CoV-2, and all results were negative.[6]

In another study on 15 pregnant women, majority of the patients presented with fever and cough, while laboratory tests yielded lymphocytopenia in 12 patients.[15] Computed tomography findings of these patients were consistent with previous reports of non-pregnant patients, consisting of ground-glass opacities at early stage.[15][16] Follow-up images after delivery showed no progression of pneumonia.[15]

Media reports indicate that over 100 women with COVID-19 might have delivered, and in March 2020, no maternal deaths were reported.[17] In April 2020, a 27-year old pregnant woman at 30 weeks of pregnancy died in Iran; her death may have been caused by COVID-19.[18]

The RCOG advised in early April 2020 that because pregnancy is a hypercoagulable state and that people admitted to hospital with COVID-19 are also hypercoagulable, infection with COVID-19 could increase the risk of venous thromboembolism and that this risk could be compounded by reduced mobility due to self-isolating.[19] Their guidelines thus advise that any pregnant woman admitted to hospital with a COVID-19 infection should receive at least 10 days of prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin after being discharged from the hospital.[20]

Recently, the International Registry of Coronavirus Exposure in Pregnancy (IRCEP) was launched as a collaboration between Pregistry and the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health.[21]

Effect on labour

There are limited data concerning the implications of COVID-19 infections for labour.[5] Al-kuraishy et al. reported that COVID-19 in pregnancy may increase the risk of preterm labour. Preterm delivery is regarded as a chief outcome of COVID-19 pneumonia during pregnancy.[19] The UKOSS study found that median gestational age at birth was 38 weeks and that 27% of women studied had preterm births. Of these, most (47%) were interventions given because of risk to the mother's health and 15% were because of risk to the foetus.[7]

Effect on the fetus

There are currently no data to suggest increased risk of miscarriage or early pregnancy loss in relation to COVID-19.[19]

Transmission

Early studies indicated no evidence for vertical transmission of COVID-19 from mother to child in late pregnancy[6] but more recent reports indicate that vertical transmission may occur in some cases.[22][23]

Early research found two neonates to be infected with COVID-19 but it was considered that transmission likely occurred in the postnatal period.[24]

It is also to be noted that the human placenta expresses factors that are important in the pathogenesis of COVID-19.[25]

More recent small-scale findings indicate that vertical transmission may be possible. One infant girl born to a mother with COVID-19 had elevated IgM levels two hours after birth, suggesting that she had been infected in utero and supporting the possibility of vertical transmission in some cases.[22] A small study involving 6 confirmed COVID-19 mothers showed no indication of SARS-CoV-2 in their newborns' throats or serum but antibodies were present in neonatal blood sera samples, including IgM in two of the infants.[23] This is not usually passed from mother to fetus so further research is required to know whether the virus crossed the placenta or whether placentas of women in the study were damaged or abnormal.[23]

A set of triplets were born prematurely with COVID-19 at the Ignacio Morones Prieto Central Hospital in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, on June 17, 2020. Both parents tested negative and the children were reported stable.[26]

Predictions

Since COVID-19 shows similarities to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, it is likely that their effect on pregnancy are similar. During the 2002–03 pandemic, 12 women who were infected with SARS-CoV were studied.[27] Four of seven had first trimester miscarriage, two of five had fetal growth restriction in the second trimester, and four of five had preterm birth. Three women died during pregnancy. None of the newborns were infected with SARS-CoV.[27] A report of ten cases of MERS- CoV infection in pregnancy in Saudi Arabia showed that the clinical presentation is variable, from mild to severe infection. The outcome was favorable in a majority of the cases, but the infant death rate was 27%.[28]

A recent review suggested that COVID-19 appeared to be less lethal to mothers and infants than SARS and MERS but that there may be an increased risk of preterm birth after 28 weeks' gestation.[29]

47 million women in 114 low and middle-income countries are projected by UNFPA to be unable to use modern contraceptives if the average lockdown, or COVID-19-related disruption, continues for 6 months with major disruptions to services: For every 3 months the lockdown continues, assuming high levels of disruption, up to 2 million additional women may be unable to use modern contraceptives. If the lockdown continues for 6 months and there are major service disruptions due to COVID-19, an additional 7 million unintended pregnancies are expected to occur by UNFPA. The number of unintended pregnancies will increase as the lockdown continues and services disruptions are extended.[30]

Recommendations

The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States advises pregnant women to do the same things as the general public to avoid infection, such as covering cough, avoid interacting with sick people, cleaning hands with soap and water or sanitizer.[2][4]

General recommendations

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) recommends seven general measures for all episodes of contact with maternity patients undergoing care:[31]

- Ensure staff and patient access to clean hand washing facilities prior to facility entry.

- Have basic soap at each health facility wash station along with a clean cloth or disposable hand towels for hand drying.

- If midwives provide direct patient care, they must frequently wash their hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds each time. This must happen before every new woman is seen and again before their physical exam. Midwives should wash again immediately after the exam and again once the patient leaves. Washing should also occur after cleaning surfaces and coughing or sneezing. Hand sanitizer can also be applied especially if clean water is unavailable.[31]

- Avoid touching the mouth, nose or eyes.

- Staff and patients should be advised to cough into a tissue or their elbow and wash hands afterwards.

- Midwives should keep a social distance of at least 2 arms lengths during any clinical visit. As long as hand washing is performed before and after the physical exam women without suspected or confirmed COVID-19, the physical exam and patient contact should continue as usual, if hand washing is performed before and after.[31]

- Spray surfaces used by patients and staff with bleach or another. Be sure to wipe down the surface with a paper towel or clean cloth in between patients and wash hands.[31]

- Childbirth, antenatal care and postnatal care are carried out by midwives and represent some of the most important health care services in the women's health sector and are directly linked to mortality and morbidity rates.[31]

- It is essential that the SRMNAH workforce, including midwives, is included in the emergency response and distribution plans to receive sufficient PPE and orientation how to use PPE correctly.[31]

- Since midwifery care is continuing to be an essential service that women must be able to access it is very important that midwives receive support, mentoring and orientation how to re-organise services to keep providing quality care (i.e. respecting the public health advice of at least 2m between women, as few as possible midwives looking after one woman (few staff in the room), hand washing hygiene).[31]

- Midwives must receive evidence-based information that they can protect themselves from contracting COVID-19 when caring for a symptomatic woman, or from a woman who was exposed to a COVID-19 positive person.[31]

- Midwives play an essential role in reducing stigma and battling the spreading belief that health facilities are to be avoided to stay healthy/ not contract COVID-19.[31]

- It can be expected that the reorganisation/ removal of funds from sectors that midwives work in, will directly be linked to an upward trend of maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality pushing countries further away from their SDG targets].[31]

Antenatal care

The RCOG and RCM strongly advise that antenatal and postnatal care should be regarded as essential, and that "pregnant women will continue to need at least as much support, advice, care and guidance in relation to pregnancy, childbirth and early parenthood as before".[19]

In May 2020, a spokesperson for the RCOG suggested that black and other minority ethnic women should be warned that they may have greater risk of complications from the virus and should be advised to seek help early if concerned.[9] Moreover, healthcare professionals should be aware of the increased risk and have a lower threshold to review, admit and escalate care provided to women of BAME background.[7]

To minimise the risk of infection, the RCOG and RCM advise that some appointments may be conducted remotely via teleconferencing or videoconferencing.[19] A survey conducted in Shanghai among pregnant women in different trimesters of pregnancy identified a strong demand for online access to health information and services.[32] Women expecting their first baby were more willing to have online consultation and guidance than who had previously given birth.[32]

The RCOG and RCM recommend that in-person appointments be deferred by 7 days after the start of symptoms of COVID-19 or 14 days if another person in the household has symptoms.[19] Where in-person appointments are required, pregnant patients with symptoms or confirmed COVID-19 who require obstetric care are advised to notify the hospital or clinic before they arrive in order for infection control to be put in place.[5][19]

Universal screening at the New York–Presbyterian Allen Hospital and Columbia University Irving Medical Center found that out of 215 pregnant patients, four (1.9%) had symptoms and were positive for COVID-19 and 29 (13.7%) were asymptomatic but tested positive for the virus.[33] Fever subsequently developed in three asymptomatic patients. One patient who had tested negative subsequently became symptomatic postpartum and tested positive three days after the initial negative test.[33] The doctors conducting the screening recommended that in order to reduce infection and allocate PPE, due to high numbers of patients presenting as asymptomatic, universal screening of pregnant patients should be conducted.[33]

During labour

In the UK, official guidelines state that women should be permitted and encouraged to have one asymptomatic birth partner present with them during their labour and birth.[19]

There is no evidence regarding if there is vaginal shedding of the virus, so the mode of birth (vaginal or caesarean) should be discussed with the woman in labour and take into consideration her preferences if there are no other contraindications.[17][19] If a patient has a scheduled elective caesarean birth or a planned induction of labour, an individual assessment should consider whether it is safe to delay the procedure to minimise the risk of infecting others.[19] Products of conception, such as the placenta, amnion etc. have not been shown to have congenital coronavirus exposure or infection, and do not pose risk of coronavirus infection.[34]

The RCOG and the RCM recommend that epidurals should be recommended to patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 in labour so that the need for general anaesthesia is minimised if urgent intervention for birth is required.[19] They also suggest that women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should have continuous electronic fetal monitoring.[19] The use of birthing pools is not recommended for suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 due to the risk of infection via faeces.[19]

Postnatal care

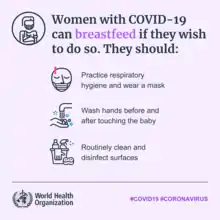

In the UK, official recommendations state that precautionary separation of a mother and a healthy baby should not be undertaken lightly and that they should be kept together in the postpartum period where neonatal care is not required.[19] According to UN Population Fund, women are encouraged to breastfeed as normal to the extent possible in consultation with the healthcare provider.[34]

Literature from China recommended separation of infected mothers from babies for 14 days.[19] In the US there is also the recommendation that newborns and mothers should be temporarily separated until transmission-based precautions are discontinued, and that where this is not possible the newborn should be kept 2 metres away from the mother.[5]

UNFPA recommends it is critical that all women have access to safe birth, the continuum of antenatal and postnatal care, including screening tests according to national guidelines and standards, especially in epicenters of the pandemic, where access to services for pregnant women, women in labour and delivery, and lactating women is negatively impacted.[35]

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women

According to UN Women, the diversion of attention and critical resources away from women's reproductive health could exacerbate maternal mortality and morbidity and increase the rate of adolescent pregnancies.[36] The United Nations Population Fund recommends that having access to safe birth, antenatal care, postnatal care and screening tests according to national guidelines is critical, particularly in areas where the pandemic has overwhelmed hospitals, so that reproductive health is negatively impacted.[34]

See also

References

- Burgos, Diario de (2020-03-30). "Muere en La Coruña una embarazada con Covid-19 de 37 años". Diario de Burgos (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Favre, Guillaume; Pomar, Léo; Musso, Didier; Baud, David (22 February 2020). "2019-nCoV epidemic: what about pregnancies?". The Lancet. 395 (10224): e40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30311-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7133555. PMID 32035511. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Q&A on COVID-19, pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding". www.who.int. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Mimouni, Francis; Lakshminrusimha, Satyan; Pearlman, Stephen A.; Raju, Tonse; Gallagher, Patrick G.; Mendlovic, Joseph (2020-04-10). "Perinatal aspects on the covid-19 pandemic: a practical resource for perinatal–neonatal specialists". Journal of Perinatology. 40 (5): 820–826. doi:10.1038/s41372-020-0665-6. ISSN 1476-5543. PMC 7147357. PMID 32277162.

- Chen, Huijun; Guo, Juanjuan; Wang, Chen; Luo, Fan; Yu, Xuechen; Zhang, Wei; Li, Jiafu; Zhao, Dongchi; Xu, Dan; Gong, Qing; Liao, Jing; Yang, Huixia; Hou, Wei; Zhang, Yuanzhen (7 March 2020). "Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records". The Lancet. 395 (10226): 809–815. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159281. PMID 32151335. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection and pregnancy Version 9" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 13 May 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- "Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, Maternal and Newborn Health & COVID-19". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "RCOG and RCM respond to UKOSS study of more than 400 pregnant women hospitalised with coronavirus". Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 11 May 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, Morris E, Simpson N, Gale C, O'Brien P, Quigley M, Brocklehurst P, Kurinczuk JJ (8 June 2020). "Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalised with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK: a national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS)". BMJ. 369: m2107. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2107. PMC 7277610. PMID 32513659.

- Rimmer MP, Al Wattar BH, et al. (UKARCOG Members) (27 May 2020). "Provision of obstetrics and gynaecology services during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a survey of junior doctors in the UK National Health Service". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 127 (9): 1123–1128. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.16313. ISSN 1470-0328. PMC 7283977. PMID 32460422.

- http://ukarcog.org/

- Breslin, Noelle; Baptiste, Caitlin; Gyamfi-Bannerman, Cynthia; Miller, Russell; Martinez, Rebecca; Bernstein, Kyra; Ring, Laurence; Landau, Ruth; Purisch, Stephanie; Friedman, Alexander M.; Fuchs, Karin (2020-04-09). "COVID-19 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: Two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM: 100118. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118. ISSN 2589-9333. PMC 7144599. PMID 32292903.

- Liu, Dehan; Li, Lin; Wu, Xin; Zheng, Dandan; Wang, Jiazheng; Yang, Lian; Zheng, Chuansheng (2020-03-18). "Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Women With Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: A Preliminary Analysis". American Journal of Roentgenology. 215 (1): 127–132. doi:10.2214/AJR.20.23072. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 32186894. S2CID 213185956.

- Liu, Dehan; Li, Lin; Wu, Xin; Zheng, Dandan; Wang, Jiazheng; Yang, Lian; Zheng, Chuansheng (2020-03-18). "Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Women With Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: A Preliminary Analysis". American Journal of Roentgenology. 215: 127–132. doi:10.2214/AJR.20.23072. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 32186894. S2CID 213185956.

- Salehi, Sana; Abedi, Aidin; Balakrishnan, Sudheer; Gholamrezanezhad, Ali (2020-03-14). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review of Imaging Findings in 919 Patients". American Journal of Roentgenology. 215 (1): 87–93. doi:10.2214/AJR.20.23034. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 32174129.

- Liang, Huan; Acharya, Ganesh (2020). "Novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy: What clinical recommendations to follow?". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 99 (4): 439–442. doi:10.1111/aogs.13836. ISSN 1600-0412. PMID 32141062. S2CID 212569131.

- Karami, Parisa; Naghavi, Maliheh; Feyzi, Abdolamir; Aghamohammadi, Mehdi; Novin, Mohammad Sadegh; Mobaien, Ahmadreza; Qorbanisani, Mohamad; Karami, Aida; Norooznezhad, Amir Hossein (2020-04-11). "Mortality of a pregnant patient diagnosed with COVID-19: A case report with clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease: 101665. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101665. ISSN 1477-8939. PMC 7151464. PMID 32283217.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection and pregnancy Version 7". Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in Pregnancy (PDF) (Report). RCOG. 24 July 2020. p. 49. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- "International Registry of Coronavirus Exposure in Pregnancy (IRCEP)". corona.pregistry.com. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Dong, Lan; Tian, Jinhua; He, Songming; Zhu, Chuchao; Wang, Jian; Liu, Chen; Yang, Jing (2020-03-26). "Possible Vertical Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 From an Infected Mother to Her Newborn". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4621. PMC 7099527. PMID 32215581.

- Zeng, Hui; Xu, Chen; Fan, Junli; Tang, Yueting; Deng, Qiaoling; Zhang, Wei; Long, Xinghua (2020-03-26). "Antibodies in Infants Born to Mothers With COVID-19 Pneumonia". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4861. PMC 7099444. PMID 32215589.

- Qiao, Jie (7 March 2020). "What are the risks of COVID-19 infection in pregnant women?". The Lancet. 395 (10226): 760–762. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30365-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7158939. PMID 32151334. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Ashary N, Bhide A, Chakraborty P, Colaco S, Mishra A, Chhabria K, Jolly MK, Modi D (19 August 2020). "Single-Cell RNA-seq Identifies Cell Subsets in Human Placenta That Highly Expresses Factors Driving Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2". Front Cell Dev Biol. 8: 783. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00783. PMC 7466449. PMID 32974340.

- "Newborn triplets diagnosed with Covid-19 in stable condition, say Mexican health officials". CNN. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Wong, Shell F.; Chow, Kam M.; Leung, Tse N.; Ng, Wai F.; Ng, Tak K.; Shek, Chi C.; Ng, Pak C.; Lam, Pansy W. Y.; Ho, Lau C.; To, William W. K.; Lai, Sik T.; Yan, Wing W.; Tan, Peggy Y. H. (1 July 2004). "Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 191 (1): 292–297. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.019. ISSN 0002-9378. PMC 7137614. PMID 15295381. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Alfaraj, Sarah H.; Al-Tawfiq, Jaffar A.; Memish, Ziad A. (1 June 2019). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection during pregnancy: Report of two cases & review of the literature". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 52 (3): 501–503. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2018.04.005. ISSN 1684-1182. PMC 7128238. PMID 29907538.

- Mullins, E.; Evans, D.; Viner, R. M.; O'Brien, P.; Morris, E. (2020). "Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: rapid review". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. n/a (n/a): 586–592. doi:10.1002/uog.22014. ISSN 1469-0705. PMID 32180292. S2CID 212739349.

- Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage (PDF). UNFPA. 2020.

- "COVID-19 Technical Brief for Maternity Services". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- Du, L.; Gu, Y. B.; Cui, M. Q.; Li, W. X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L. P.; Xu, B. (2020-03-25). "[Investigation on demands for antenatal care services among 2 002 pregnant women during the epidemic of COVID-19 in Shanghai]". Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 55 (3): 160–165. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112141-20200218-00112. ISSN 0529-567X. PMID 32268713. S2CID 215611766.

- Sutton, Desmond; Fuchs, Karin; D’Alton, Mary; Goffman, Dena (2020-04-13). "Universal Screening for SARS-CoV-2 in Women Admitted for Delivery". New England Journal of Medicine. 0 (22): 2163–2164. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2009316. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 7175422. PMID 32283004.

- "COVID-19 Technical Brief for Maternity Services". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "COVID-19 Technical Brief for Maternity Services". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- "UN Secretary-General's policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women | Digital library: Publications". UN Women. Retrieved 5 June 2020.