Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on politics

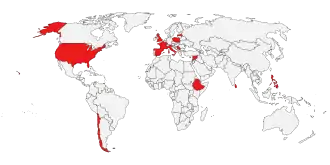

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted politics, both international and domestic, by affecting the governing & political systems of multiple countries, causing suspensions of legislative activities, isolation or deaths of multiple politicians and reschedulings of elections due to fears of spreading the virus. The pandemic has triggered broader debates about political issues such as the relative advantages of democracy and autocracy,[1][2] how states respond to crises,[3] politicization of beliefs about the virus,[4] and the adequacy of existing frameworks of international cooperation.[5] Additionally, the pandemic has, in some cases, posed several challenges to democracy, leading to it being fatally undermined and damaged.[6]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

General impacts

The response to the pandemic has resulted in unprecedented expansion of government power. Advocates of small government worry that the state will be reluctant to give up that power once the crisis is over, as has often been the case historically.[7]

Leader popularity

There is evidence that the pandemic has caused a rally-round-the-flag effect in many countries, with government approval ratings rising in Italy (+27 percentage points), Germany (+11), France (+11), and the United Kingdom.[8][9][10] In the United States, President Donald Trump has seen a 6-point drop in approval,[11] while state governors have seen increases as high as 55 points for New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, 31 points for North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, and 30 points for Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer.[9]

States of emergency

At least 84 countries have declared a state of emergency in response to the pandemic, leading to fears about misuse of power.[12] Reporters Without Borders has claimed that 38 countries have restricted freedom of the press as a result.[12] Other examples include banning mass protests, postponing elections or holding them while the opposition cannot effectively campaign, selectively enforcing lockdown rules on political opponents, handing out relief payments to political supporters, or scapegoating minorities.[13] Many countries have also unveiled large-scale surveillance programs for contact tracing, leading to worries about their impact on privacy.[14]

Human rights & freedoms

Whilst the emergency powers enacted by governments in order to stem the spread of the pandemic were made in good faith of protecting public health and minimising risk to countries’ economies and crucial services, such as health care, in many cases they inadvertently led to more pressures on human rights and civil liberties than perhaps intended. As a result of angered citizens and extrajudicial force taken by government actors such as police and security forces, many populations experienced undue and out of proportion violence and oppression, such as the highly militarised response seen in the Philippines which led to government forces violently detaining, attacking, and even killing citizens who flouted restrictive laws, with the authorities often citing tenuously related or far-reaching reasons to justify their actions.[15] Lesser examples of violent clashes between citizens and armed government authorities have also been seen in countries including Greece, the United States, and Germany.[16] Human rights and civil liberties have also been threatened through the oppressive and intrusive abuse of digital surveillance technology by multiple governments, violating the human rights to privacy, freedom, expression and association. [17]The Ecuadorean government introduced a new GPS tracking system without any kind of appropriate data handling legislation, leaving users’ details exposed and insecure.[18] In South Korea, health authorities launched a track and trace app which asked users to disclose heavy amounts of personal information, leading to concerns over both privacy and the potential for discrimination.[19]

Democracy

The COVID-19 pandemic has also opened up gaps in the action of democracy,[6] largely due to the heavy practical and logistical disruption the virus and its subsequent “lockdown” restrictions caused. Across the globe, national governments found themselves with no other choice but to suspend, cancel, or postpone numerous democratic elections at both national and subnational governmental levels.[20] This is a major disruption to democracy, challenging its very nature and contradicting the idea of fixed governmental terms (which are of course vital in true democracies).[21]

The media

Media, in its many forms, has also suffered greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic.[22]With the spread of the virus and subsequent government measures chasing unrest in many countries, multiple governments introduced new restrictions on media outlets in order to try and prevent the spread of misinformation, poor representations of governments and their nations, and in many cases, the truth - from being leaked to the outside world.[23] These restrictions allowed media outlets and journalists to be prosecuted and imprisoned more easily, often unfairly and arbitrarily.[24]Some governments even stopped media outlets from criticising them, a breach of freedom of expression; article 19 of the UDHR.[17]

Impact on international relations

European Union

The Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez stated that "If we don't propose now a unified, powerful and effective response to this economic crisis, not only the impact will be tougher, but its effects will last longer and we will be putting at risk the entire European project", while the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte commented that "the whole European project risks losing its raison d'être in the eyes of our own citizens".[25] From 4 to 19 March, Germany banned the export of personal protective equipment,[26][27] and France also restricted exports of medical equipment, drawing criticism from EU officials who called for solidarity.[28] Many Schengen Area countries closed their borders to stem the spread of the virus.[29]

Jointly issued debt

Debates over how to respond to the epidemic and its economic fallout have opened up a rift between Northern and Southern European member states, reminiscent of debates over the 2010s European debt crisis.[30] Nine EU countries—Italy, France, Belgium, Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland, Slovenia and Luxembourg—called for "corona bonds" (a type of eurobond) in order to help their countries to recover from the epidemic, on 25 March. Their letter stated, "The case for such a common instrument is strong, since we are all facing a symmetric external shock."[31][32] Northern European countries such as Germany, Austria, Finland, and the Netherlands oppose the issuing of joint debt, fearing that they would have to pay it back in the event of a default. Instead, they propose that countries should apply for loans from the European Stability Mechanism.[33][34] Corona bonds were discussed on 26 March 2020 in a European Council meeting, which dragged out for three hours longer than expected due to the "emotional" reactions of the prime ministers of Spain and Italy.[35][36] European Council President Charles Michel[34] and European Central Bank head Christine Lagarde have urged the EU to consider issuing joint debt.[36] Unlike the European debt crisis—partly caused by the affected countries—southern European countries did not cause the coronavirus pandemic, therefore eliminating the appeal to national responsibility.[33]

Civil liberties

Sixteen member nations of the European Union issued a statement warning that certain emergency measures issued by countries during the coronavirus pandemic could undermine the principles of rule of law and democracy on 1 April. They announced that they "support the European Commission initiative to monitor the emergency measures and their application to ensure the fundamental values of the Union are upheld."[37] The statement does not mention Hungary, but observers believe that it implicitly refers to a Hungarian law granting plenary power to the Hungarian Government during the coronavirus pandemic. The following day, the Hungarian Government joined the statement.[38][39]

The Hungarian parliament passed the law granting plenary power to the Government by qualified majority, 137 to 53 votes in favor, on 30 March 2020. After promulgating the law, the President of Hungary, János Áder, announced that he had concluded that the time frame of the Government's authorization would be definite and its scope would be limited.[40][41][42][43] Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission, stated that she was concerned about the Hungarian emergency measures and that it should be limited to what is necessary and Minister of State Michael Roth suggested that economic sanctions should be used against Hungary.[44][45]

The heads of thirteen member parties of the European People's Party (EPP) made a proposal to expunge the Hungarian Fidesz for the new legislation on 2 April. In response, Viktor Orbán expressed his willingness to discuss any issues relating to Fidesz's membership "once the pandemic is over" in a letter addressed to the Secretary General of EPP Antonio López-Istúriz White. Referring to the thirteen leading politicians' proposal, Orbán also stated that "I can hardly imagine that any of us having time for fantasies about the intentions of other countries. This seems to be a costly luxury these days."[46] During a video conference of the foreign ministers of the European Union member states on 3 April 2020, Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Péter Szijjártó, asked for the other ministers to read the legislation itself not its politically motivated presentations in newspapers before commenting on it.[47]

Japan–South Korea relations

Japan–South Korea relations worsened as a result of the pandemic.[48] After Japan declared it would start quarantining all arrivals from South Korea, the South Korean government described the move as "unreasonable, excessive and extremely regrettable", and that it couldn't "help but question whether Japan has other motives than containing the outbreak".[49] Some South Korean media have offered opinions to improve relations with Japan through mask assistance to Japan.[50] In addition, some local governments in Japan who did not disclose their names have also announced their intention to purchase masks in Korea.[51] When this fact became known, some online commentators in Japan expressed that they would never receive a mask even if it came from Korea, as it would not be free, as it would be a public pressure for concede of the Japanese government if South Korea gave masks to Japan.[52] However, the Korean government has never reviewed the support of masks to Japan, and expressed that it would only proceed with the formally disclosed request of the Japanese government for supply support such as facial mask, following the public opinion of the Korean people.[53] On the contrary, inside Japan, an editorial was published stating that the Korean government should donate medical supplies like face mask covertly and the Japanese government should accept it casually.[54]

China

The United States has criticised the Chinese government for its handling of the pandemic, which began in the Chinese province of Hubei.[55] In Brazil, the Congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, son of President Jair Bolsonaro, caused a diplomatic dispute with China when he retweeted a message saying: "The blame for the global coronavirus pandemic has a name and surname: the Chinese Communist party." Yang Wanming, China's top diplomat in Brazil, retweeted a message that said: "The Bolsonaro family is the great poison of this country."[56]

Some commentators believe the state propaganda in China is promoting a narrative that China's authoritarian system is uniquely capable of curbing the coronavirus and contrasts that with the chaotic response of the Western democracies.[57][58][59] European Union foreign policy chief Josep Borrell said that "China is aggressively pushing the message that, unlike the US, it is a responsible and reliable partner."[60]

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has claimed that the United States military is behind the virus.[61] When Australia suggested an inquiry to better understand the origin of the pandemic and to undermine the World Health Organization, the Chinese ambassador threatened with economic retaliation.[61] The Chinese embassy to France has in turn claimed that French nursing homes were ""abandoning their posts overnight … and leaving their residents to die of hunger and disease".[61] The Chinese government has also tried to directly influence statements of other governments in order to show the country in a more positive light, including in Germany,[62] and Wisconsin.[63]

China has sent aid to 82 countries, the World Health Organization, and the African Union, which is considered by some western media as to "counter its negative image in the early stage of the pandemic".[64][65] According to Yangyang Cheng, a postdoctoral research associate at Cornell University, "The Chinese government has been trying to project Chinese state power beyond its borders and establish China as a global leader, not dissimilar to what the U.S. government has been doing for the better part of a century, and the distribution of medical aid is part of this mission." Borrell warned that there is "a geo-political component including a struggle for influence through spinning and the 'politics of generosity'."[60]

Trade in medical supplies between the United States and China has also become politically complicated. Exports of face masks and other medical equipment to China from the United States (and many other countries) spiked in February, according to statistics from Trade Data Monitor, prompting criticism from the Washington Post that the United States government failed to anticipate the domestic needs for that equipment.[67] Similarly, The Wall Street Journal, citing Trade Data Monitor to show that China is the leading source of many key medical supplies, raised concerns that US tariffs on imports from China threaten imports of medical supplies into the United States.[68]

United States

In early March, European Union leaders condemned the United States' decision to restrict travel from Europe to the United States.[69]

The U.S. has come under scrutiny by officials from other countries for allegedly hijacking shipments of crucial supplies meant for other countries.[70][71]

Jean Rottner, the President of France's Regional council of Grand Est, accused the United States of disrupting face mask deliveries by buying at the last minute.[72] French officials stated that Americans came to the airport tarmac and offered several times the French payment as the shipment was prepared for departure to France.[71] Justin Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada, asked Bill Blair, the Public Safety Minister, and Marc Garneau, the Transportation Minister, to investigate allegations that medical supplies originally intended for Canada were diverted to the United States.[73] German politician Andreas Geisel accused the United States of committing "modern piracy" after reports that 200,000 N95 masks meant for German police were diverted during an en-route transfer between airplanes in Thailand to the United States,[74] but later changed his statement after he clarified that the mask orders were made through a German firm, not a U.S. firm as earlier stated, and the supply chain issues were under review.[75]

Due to shortages in coronavirus tests Maryland Governor Larry Hogan had his wife Yumi Hogan, who was born in South Korea, to speak with the South Korean ambassador and afterwards multiple South Korea companies stated that they would send tests to Maryland.[76]

On 2 April 2020, President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act of 1950 to halt exports of masks produced by 3M to Canada and Latin America.[77] Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that it would be a mistake for both their countries to limit trade of essential goods or services, including medical supplies and professionals, and remarked that this moves in both directions.[77] The Canadian government has turned to China and other places for crucial medical supplies, while they seek a constructive discussion about the issue with the Trump administration.[78]

In October 2020, the editors of the New England Journal of Medicine unanimously published an unprecedented editorial calling for the current American leadership to be voted out in the November election, writing "countries were forced to make hard choices about how to respond. Here in the United States, our leaders have failed that test. They have taken a crisis and turned it into a tragedy."[79] Science Advances also published a research study that revealed "states with more COVID-19 fatalities were less likely to support Republican candidates." [80]

In November 2020, Donald Trump lost his bid for reelection to former Vice President Joe Biden, in an election dominated by COVID-19's impact on all aspects of American life.[81]

As of December 30, 2020, two federal politicians, eight state politicians, and five local politicians have died from COVID-19.[82]

World Health Organization

The head of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom, claimed that he had been "severely discriminated against", and had received death threats and racist insults, claiming that "This attack came from Taiwan".[83] The foreign ministry of Taiwan protested this accusation, indicating "strong dissatisfaction and a high degree of regret" and that the Taiwanese people "condemn all forms of discrimination and injustice".[83]

On 7 April 2020, United States President Donald Trump threatened to cut funding to the WHO.[84] On 7 July 2020, the Trump administration announced that the United States would formally withdraw from the WHO.[85] On 22 January 2021, president Joe Biden's rejoin the United States to the World Health Organization.[86]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría wrote that “This is the third and greatest economic, financial and social shock of the 21st century, and it demands a modern, global effort akin to the last century’s Marshall Plan and New Deal – combined.[87]” COVID-19 has a strong regional and global impact, calling for differentiated governance and policy responses from local to international levels. A coordinated response by all levels of government can minimize crisis-management failures.[88]

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) planned to discuss Guyana and Venezuela border dispute over Guayana Esequiba in March 2020. The ICJ also delayed public hearings over maritime border disputes between Somalia and Kenya until March 2021.[89] Both hearings were postponed due to the pandemic.[90][91]

Global ceasefire

The coronavirus pandemic appears to have worsened conflict dynamics;[92] it has also led to a United Nations Security Council resolution demanding a global ceasefire. On March 23, 2020, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres issued an appeal for a global ceasefire as part of the United Nations' response to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.[93][94] On 24 June 2020, 170 UN Member States and Observers signed a non-binding statement in support of the appeal,[95] rising to 172 on 25 June 2020. On 1 July 2020, the UN Security Council passed resolution S/RES/2532 (2020), demanding a "general and immediate cessation of hostilities in all situations on its agenda," expressing support for "the efforts undertaken by the Secretary-General and his Special Representatives and Special Envoys in that respect," calling for "all parties to armed conflicts to engage immediately in a durable humanitarian pause" of at least 90 consecutive days, and calling for greater international cooperation to address the pandemic.

Impact on national politics

Belgium

On 17 March 2020, Sophie Wilmès was sworn in as Prime Minister of Belgium. Seven opposition parties pledged to support the minority Wilmès II Government, in its previous composition, with plenary power to handle the coronavirus pandemic in Belgium.[96]

Brazil

President Jair Bolsonaro has been criticized for his handling of the crisis.[97] He has referred to the pandemic as a "fantasy".[98] According to one poll, 64% of Brazilians reject the way Bolsonaro has handled the pandemic, while 44.8% support his impeachment, an all-time high.[99] During a speech by the president about the pandemic, many Brazilians participated in a panelaço protesting the president by banging pots and pans on balconies.[100][101]

Canada

On 13 March 2020, the Parliament of Canada voted to suspend activity in both houses until 20 April for the House of Commons and 21 April for the Senate.[102] The House of Commons' Health and Finance committees were granted the ability to hold weekly virtual meetings during the pandemic.[103]

The leadership contests of the Conservative Party of Canada, Green Party of British Columbia, Quebec Liberal Party and Parti Québécois were postponed.[104][105][106][107]

On the 1st December 2020, the Canadian federal government announced plans for a $100 billion to kick-start the countries post-pandemic economy. Which is its biggest relief package since the Second World War and it will account for about to 3-4% of Canada's GDP and will bring the countries deficit to $381.6 billion. [108]

On the 7th January the Canadian government made it compulsory that to travel to Canada that you must have returned a negative COVID-19 test prior to travel. It was introduced to try and prevent new strains of COVID-19 from entering thee country. [109]This was to extends the restrictions on entry further from the 26th March 2020 which saw a requirement that made it mandatory to isolate after entering Canada except if you were from the USA.[110]

China

Multiple provincial-level administrators of the Communist Party of China (CPC) were dismissed over their handling of the quarantine efforts in central China. Some experts believe this is likely in a move to protect Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping from people's anger over the coronavirus outbreak.[111] Taiwan has also voiced concern over being included in any travel ban involving the People's Republic of China due to the "one-China policy" and Chinese claims.[112] A few countries have been using the epidemic to build political bridges with Beijing, raising accusations that these countries, which include Cambodia among others, were putting politics before health.[113] Existing tensions between the United States and China may have delayed a coordinated effort to combat the outbreak in Wuhan.[114]

Outlets such as Politico, Foreign Policy, and Bloomberg have reported that efforts from China to send aid to other countries and claim without evidence that the virus originated in the United States are a propaganda push for global influence while deflecting blame for its handling of the outbreak.[115][58][59]

Hong Kong

Protests in Hong Kong strengthened due to fears of immigration from mainland China.[116] In order to crackdown Hong Kong protests, China drift a new Hong Kong national security law which have drawn international concerns.

Hungary

The Hungarian Parliament gave the government plenary power which authorizes it to override acts and to rule by decree to the extent that is "necessary and proportional" in order to "prevent, manage, and eradicate the epidemic and to avoid and mitigate its effects".[117] The law prescribes that the government is to report back to the parliament, or if it's unable to convene, to its speaker and the leaders of the parliamentary groups, regularly about the measures it has taken.[117] The law also suspends by-elections and referendums for the duration of the emergency.[118][117] The Constitutional Court of Hungary is authorized to hold sessions via electronic communications networks.[117] The act also criminalizes "statements known to be false or statements distorting true facts" with 1 to 5 years imprisonment "if done in a manner capable of hindering or derailing the effectiveness of the response effort".[117] The opposition had demanded a 90-day sunset clause to the emergency powers in return for its support, but had its amendments voted down and therefore opposed the act.[117]

Human Rights Watch described the legislation as an authoritarian takeover, due to the rule of decree supposedly without parliamentary or judicial scrutiny and for criminal penalties for the publishing of "false" or "distorted" facts, and gave support to the European Commission using Article 7 against Hungary. Criticism and concern regarding the decree stemmed from existing backsliding of Hungarian democracy under the premiership of Viktor Orbán and his majority-ruling Fidesz party since Orbán began his second tenure as Prime Minister in 2010. Orbán has been accused by opposition leaders and other critics of his premiership of shifting Hungary towards authoritarianism by centralizing legislative and executive power through Constitutional reforms passed in 2011 and 2013, curbing civil liberties, restricting freedom of speech to the extent that some independent media outlets once critical of his rule have since been acquired by allies of Orbán, and weakening other institutional checks on Orbán's power including the Constitutional Court and judiciary. Critics of the Orbán/Fidesz government expressed concern that the emergency plenary powers may not be rescinded once the pandemic subsides, and could be abused to dubiously prosecute independent journalists critical of his coronavirus response or his governance more broadly, and curtail other freedoms of speech and expression. Some observers suggest that any significant misuse of or, once the crisis subsides, failure to rescind the plenary powers by Orbán government could place Hungary at great risk of becoming the European Union's first dictatorship, in violation of E.U. regulations.[119][120][121][122] A petition against the legislation was signed by over 100,000 people. Péter Jakab, the president of the opposition party Jobbik, said that the bill put Hungarian democracy in quarantine. Nézőpont, a pro-government polling agency, conducted a poll that showed that 90% of Hungarians supported extending emergency measures and 72% supported strengthening the criminal code.[123]

In response to news reports about the state of emergency being a danger to democracy, Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó called them "fake news and lies" and stated that the measures that Hungary had adopted were not unprecedented in Europe. He specifically stated that there were unfounded reports in mainstream media about the government's unlimited authorization and the closing down of the Parliament.[124]

European Commission vice-president Věra Jourová after a thorough examination confirmed that Hungary's recently adopted emergency measures do not break any EU rules.[125][126]

Iran

The Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran has been heavily affected by the virus.[127] The spread of the virus has raised questions about the future survival of the regime.[128] Iran's President Hassan Rouhani wrote a public letter to world leaders asking for help, saying that his country doesn't have access to international markets due to the United States sanctions against Iran.[129] On 3 March 2020, Iranian Parliament was shut down after having 23 of the 290 members of parliament reported to have had tested positive for the virus.[130]

Israel

After facing political deadlock since the legislative election held on 9 April 2019, Israel held two more elections in 2020, which ended with Netanyahu forming the Thirty-fifth government of Israel.

On 28 March 2020, the United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, Nickolay Mladenov praised the Israel and Palestinian authorities for their coordination in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic. Mladenov appreciated the response strategy, especially for focusing on Gaza, as the region faces a relatively substantial risk of the disease spreading. Since the start of the novel coronavirus crisis, Israel permitted the entry of significant medical and aid supplies inside Gaza.[131]

Kosovo

On 18 March, Interior Minister Agim Veliu was sacked due to his support for declaring a state of emergency to handle the coronavirus pandemic which would have given power to the Kosovo Security Council chaired by Hashim Thaçi. The Democratic League of Kosovo, the junior partner leader of the coalition, filed a no-confidence vote motion in retaliation for the sacking and on 25 March eighty two members of the Kosovo Assembly voted in favor of the motion.[132][133]

Slovenia

On its 1st Session on 13 March 2020, immediately following its confirmation, the 13th Government set up an informal Crisis Management Staff (CMS) of the Republic of Slovenia in order to contain and manage the COVID-19 epidemic. Head of the Staff was Prime Minister Janez Janša and its secretary was former SOVA director Andrej Rupnik. CMS was composed of all government members (prime minister and ministers) and other experts and civil servants in an advisory capacity.[134] Head of the Health Group was Bojana Beovič.[135] Jelko Kacin, former minister and ambassador to NATO, was the official spokesman of the Staff, he had a similar role during the 1991 Slovenian war of independence.[136]

Crisis Management Staff was abolished on 24 March 2020 after the political transition was completed, its functions were transferred on the responsible ministries. Health Experts Group was transferred under the Ministry of Health. Kacin became the official government spokesperson on the topic.[137]

Government never proposed the declaration of emergency to the National Assembly, which would suspend the Assembly's powers and transfer them to the President of the Republic Borut Pahor to rule by decrees with the force of law, which are still subject to the National Assembly's approval once it gains its powers back. The provision is only applicable if the National Assembly is unable to meet in the session.[138] Assembly however passed a Rules of Procedure Amendment to enable itself a "long-distance" session using technology.[139]

South Korea

Diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea worsened, as South Korea criticized Japan's "ambiguous and passive quarantine efforts", after Japan announced anybody coming from South Korea will be placed in two weeks’ quarantine at government-designated sites.[140]

Following the outbreak of the virus in South Korea over 1,450,000 people signed a petition supporting the impeachment of President Moon Jae-in due to him sending masks and medical supplies to China to aid them in their response to the virus outbreak.[141] Moon administration's continuing handling of the crisis has however been noted in other sectors of the Korean society and internationally. An opinion poll by Gallup Korea in March 2020 showed Moon's approval rating rising by 5% to 49%.[142]

In April 2020, Moon's Democratic Party won a record landslide in the country's legislative election for 21st session until 2024.[143][144]

Spain

On 12 March 2020, the Congress of Deputies voted to suspend activity for a week after multiple members had tested positive for the virus.[145] When the Congress of Deputies approved the extension of the State of Alarm on 18 March, it was the first time that opposition parties Popular Party and Vox had supported the government in a vote while separatist parties, such as Catalan Republican Left, abstained from the vote.[146]

The response to the coronavirus has been complicated by the fact that Pedro Sánchez is leading PSOE (in coalition with Unidas Podemos) minority government which is counting on support from opposition parties to enact coronavirus measures, especially with regards to economic stimulus. So far, the cabinet is discussing proposals to offer zero-interest loans to tenants to pay rent so that smaller landlords who depend on rent income can stay afloat. PP leader Pablo Casado complained that the government was not keeping him informed of developments on the coronavirus. Ciudadanos leader Inés Arrimadas said that she supports the government's actions.[146]

United Kingdom

The timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK highlights both successes and failures in the government's response to containing and then controlling the disease, but will also highlight their political and social actions which have had a series of mixed results.

On the 5th March, Health minister Nadine Dorries was the first parliamentarian to show COVID-19 symptoms.[147] MP Kate Osborne showed them some days later.[148] On the 13th March, the 2020 United Kingdom local elections were postponed for a year,[149] the longest postponement of democratic elections in the UK since the interwar period.[150] In late March, the UK, Scottish and Welsh Parliaments scaled back their activities.[151]

On the 23rd March, a national lockdown is announced by Boris Johnson in an attempt to reduce the spread of COVID-19, where all non-essential businesses are told to shut down, households prevented from mixing and limited outdoor interaction.[152] A financial support package is announced on the 26th March nicknamed the furlough scheme which should cover 80% of self-employed earnings over the past three years.[153]

On 27 March, both Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Matt Hancock announced that they had tested positive for the virus.[154] On the same day, Labour Party MP Angela Rayner, the Shadow Secretary of State for Education, confirmed she had been suffering symptoms and was self-isolating.[155] Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty also reported suffering from symptoms and would be self-isolating, while continuing to advise the UK government.[156]

The 28th March marked the first death of a frontline NHS worker,[157] with Amged El-Hawrani, a 55-year-old consultant dying after testing positive for coronavirus.

On 30 March the Prime Minister's senior adviser Dominic Cummings was reported to be self-isolating after experiencing coronavirus symptoms. He had been at Downing Street on 27 March and was stated to have developed symptoms over 28 and 29 March.[158]

On 2 April, the world reaches 1 million confirmed cases of coronavirus,[159] according to Johns Hopkins University, with Boris Johnson coming out of self-isolation on the same day. A new Labour leader is elected on the 4th April, Sir Keir Starmer replacing Jeremy Corbyn as the Labour Party's leader, amidst growing cases and deaths in the UK. Over the coming days, the Prime Minister is moved back into hospital with worsening conditions, and is placed into intensive care as a precautionary measure,[160] but later moved back onto the standard COVID wards.

On the 8th April, the first major cracks in government policy appear as various medical associations speak-out about the dangerously low levels of PPE available which is endangering patients health.[161] The government is criticised later that month with a BBC report coming out suggesting ministers failed to organise PPE to be stockpiled, and that advice was ignored when they were told to fill the gap in missing equipment by their own advisers, putting at risk both patients and staff to the virus.[162] On the 23rd April, millions of people become eligible for a coronavirus test after a large expansion went underway for essential workers and their households,[163] and on the same day the first element of human trials in the UK for the virus vaccine begin, lead by Oxford University.[164]

The 1st May represents a victory for the government as they hit their testing target of 100,000 tests per day on the 30th April,[165] and although this was prior to the death toll in the UK surpassing Italy on the 5th May, becoming the highest in Europe.[166] The 7th May also brings a new, horrifying statistic regarding black men and women in England and Wales as being more than four times more likely to die from a coronavirus related death than white people,[167] according to the ONS. The 10th May is the day where the nation can finally start to breathe again, with lockdown restrictions eased slightly over the course of the next few days and some outdoor shops like Garden Center's finally reopening on the 11th May for the first time since March.[168] The following day on the 12th May, the Chancellor extends the furlough scheme until the end of October, but with employers picking up more of the bill as the months progress and economy opens back up.[169] The first sign of a vaccine appears on the 17th May when Oxford University sign a licensing agreement with AstraZeneca to supply 100 million doses of a vaccine.[170] On the 18th May, wider coronavirus testing becomes available for all those aged five or older if they are showing symptoms, also expanding to a loss of taste or smell.[171] On the 22nd May, Home Secretary, Priti Patel, announced on that people arriving from overseas into the UK would have to quarantine for 14 days, beginning on the 8th June.[172] Over the next few days, from the 23 to 25 May, Boris Johnson's senior aide, Dominic Cummings, comes under fire for allegedly breaking lockdown rules. Johnson defends him, prior to him making a public press conference to defend his innocence.[173]

On the 1st June, lockdown measures are eased again, with some school children heading back into the classroom.[174] The 15th June also showed some more easing of restrictions with high-streets reopening and places of worship also allowing for private prayer.[175] However we see another government failure on the 18th June, when the government abandon their own NHS track and trace app, making way for Apple and Google to take over the design.[176] This failure comes nearly a month after track and tract was launched in England on the 28th May, and with no effective way of tracking infected cases after it was announced a system would be in place by the 1st June. The failure in government policy and practicality shows a lack of organisation and capability when executing such pivotal tasks under high-pressure conditions. On the 29th June, a local lockdown is re-imposed on Leicester due to a spike in COVID-19 cases, while the rest of the country moves to further ease restrictions for social gatherings on the 4th July.[177]

The UK's travel corridor list is finally published on the 3rd of July, with 73 countries where Britons can fly to and return without having the need to quarantine,[178] while the Health Secretary announced a partial easing of restrictions in Leicester on the 16th July.[179] Although restrictions have eased, from the 24th July, shoppers are told that face masks are mandatory in England, with fines of £100 if the laws aren't respected, and only for Spain to be removed off the quarantine exemption list on the 26th July, suggests that cases may be on the rise. The end of July also reflects this with Matt Hancock warning of a second wave beginning to "roll across Europe" on the 30th July, and halting the further easing of restrictions supposed to be taking place on the 1st of August.

On the 3 August, the 'Eat Out to Help Out' scheme is launched by Rishi Sunak, with half price meals in all participating restaurants from Monday to Friday throughout August.[180] Whilst the scheme received significant praise[181] research has since shown that the government initiative drove new COVID-19 infections up by between 8 and 17%.[182] Between 10 August and 20 September, Public Health England said that among people who tested positive for COVID-19 eating out was the most commonly reported activity in the two to seven days prior to the onset of symptoms.[183]

On 13 August, A-Level students in the United Kingdom received their exam results, designated using a grades standardisation algorithm. Whilst the algorithm was designed to combat grade inflation nearly 36% of students were one grade lower than teachers' predictions and 3% were down two grades.[184] This resulted in public outcry.[185] One of the main criticisms made against grade standardisation was the apparent downgrading of results for those who attended state schools, and upgrading of results for pupils at private schools, disproportionately disadvantaging poorer students.[186][187] In response to the outcry, on the 15th August, Gavin Williamson said that the grading system is here to stay, and there will be "no U-turn, no change". Two days later on the 17th August, Ofqual and Gavin Williamson agreed to a u-turn and grades would now be reissued using unmoderated teacher predictions.[188] Despite amendments to the system many students missed out on university placements.[189]

On the 8th September the government published new social distancing guidelines to come in to effect on the 14th September, whereby household gatherings were limited to six people, termed the 'rule of six'.[190] On the 22nd September tightening of COVID-19 restrictions were announced by the UK government for England as well as the devolved administrations in the rest of the UK. These restrictions included 10pm curfews for pubs and restaurants across the UK.[191]

On the 12th October the government introduced its three-tier restriction framework across England, with legal restrictions varying according to the government-defined tiers. The three-tier system came into effect on the 14th October with Liverpool becoming the first region under Tier 3 restrictions which ordered the closure of pubs, gyms and betting shops.[192] On the 31st October, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that England would enter a four-week 'circuit-breaker' national lockdown on the 5th November, with pubs, restaurants, leisure centres and non-essential shops closing.[193]

On the 11th November, total COVID-19 deaths in the UK passed 50,000, the first European country to pass the number.[194] On the 23rd November, trials showed that the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine was 70% effective, which could be as high as 90% by tweaking the dosage.[195] However, the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine was reported to be 25% less effective than the vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna.[196]

On the 2nd December the circuit breaker lockdown ended and the three-tier system was re-implemented in England under the The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (All Tiers) (England) Regulations 2020. On the same day the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine was approved by the MHRA for use in the United Kingdom, making the UK the first country in the world to approve a COVID–19 vaccine.[197] On the 8th December, the government began its immunisation campaign, dubbed 'V-Day' by media outlets.[198]

On the 14th December it was announced that at least 60 different local authorities in the UK had recorded Covid infections caused by the a new variant, Variant of Concern 202012/01.[199] On the 19th December, it was announced that a new "tier four" measure would be applied to London, Kent, Essex, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, to try to control the spread of the new variant. Under tier four restrictions people were not permitted to interact with others from outside of their own household, even on Christmas Day.[200] Johnson announced that the relaxation of restrictions outside the new tier 4 over Christmas would now only be for Christmas Day instead of the five days originally declared.[201] On the 30th December the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine was approved for use in the United Kingdom by the MHRA for deployment the following week.[202]

On the 5th January 2021 the Prime Minister announced that England would enter its third lockdown from 5 January, with similar restrictions to the first lockdown in March 2020. On the 8th January the MHRA approved the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, the third COVID-19 vaccine approved for use in the UK.[203] On the 15th January it was announced that all 'travel corridors' would be closed from the 18th of January all arrivals to the UK will need to quarantine for up to 10 days, unless they test negative after five days.[204]

United States

Owing to the stock market crash, high unemployment claims, and reduced economic activity caused by the coronavirus pandemic the United States Congress convened to create legislation to address the economic effects of the pandemic and passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act). Representative Thomas Massie attempted to maneuver for a roll-call vote, but there was insufficient demand among the quorum present and the House passed the bill by voice vote on 27 March.[205]

The outbreak prompted calls for the United States to adopt social policies common in other wealthy countries, including universal health care, universal child care, paid sick leave, and higher levels of funding for public health.[206][207][208] Trump was also criticized for embracing medical populism, giving medical advice on Twitter and at press conferences.[209] Political analysts anticipated it may negatively affect Donald Trump's chances of re-election in the 2020 presidential election.[210][211] Some state emergency orders have waived open meeting laws that require the public have physical access to the meeting location, allowing meetings to be held by public teleconference.[212][213]

On 19 March, ProPublica published an article showing that Senator Richard Burr has sold between $628,000 and $1.7 million worth of stocks before the stock market crash using insider knowledge from a closed Senate meeting where Senators were briefed on how coronavirus could affect the United States. Stock transactions committed by Senators Dianne Feinstein, Kelly Loeffler, and Jim Inhofe were also placed under scrutiny for insider trading.[214] On 30 March, the Department of Justice imitated a probe into the stock transactions with the Securities and Exchange Commission.[215]

Captain Brett Crozier wrote a four-page memo requesting help for his crew, as a viral outbreak had occurred on board his ship, the USS Theodore Roosevelt.[216][217] However, he was soon relieved of his command over the ship, because the memo was leaked to the public.[216][217] The Acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly initially justified his actions to fire Crozier, saying that the captain was "too naive or too stupid" to be a commanding officer if he did not think that the information would get out to the public in this information age, but later issued an apology in which he acknowledged that Crozier intended to draw public attention to the circumstances on his ship.[216][217] Several members of Congress called for Modly's resignation for his handling of the situation,[216] which he did on 7 April.[217]

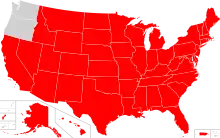

State

.jpg.webp)

Multiple U.S. states suspended legislative activity including Colorado, Kentucky, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, New Hampshire, and Vermont.[219][220][221][222]

On 11 March 2020, New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham vetoed $150 million worth on infrastructure projects due to the state losing $22 million in its general fund for every $1 decrease in the price of a barrel of oil as a result of the Russia–Saudi Arabia oil price war. The Alaska Department of Revenue delayed its release of its budget forecast due to Alaska's dependence on oil prices.[223]

On 10 March, Georgia state senator Brandon Beach started showing symptoms of COVID-19 and was tested on 14 March. However, he attended a special session of the legislature on 16 March before his test results arrived on 18 March showing that he had tested positive. The entire Georgia state senate, their staffs, and Lieutenant Governor Geoff Duncan went into quarantine until 30 March.[224]

Coronavirus restrictions also disrupted thousands of political campaigns across America, limiting the canvassing and in-person fundraising candidates have long-relied on to win office. Political insiders believe that could give incumbents a bigger advantage than normal.[225]

Venezuela

Reuters reported that during the pandemic, allies of both Nicolás Maduro and Juan Guaidó had secretly begun exploratory talks, according to sources on both sides.[226] Guaidó and U.S. Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams have denied that negotiations have taken place.[227][228]

Impact on elections

Bolivia

On 21 March 2020, President Jeanine Áñez announced the interim government's decision to postpone the snap election. Other presidential candidates had suggested postponing the election to prevent the spread of coronavirus through the congregation of large groups of people.[229][230]

Chile

A plebiscite on a new constitution and the convention that would write it was scheduled on 25 April, but on 19 March, political parties reached an agreement on postponing the plebiscite to 25 October.[231] This agreement also postponed municipal and regional elections, from 25 October to 4 April 2021, with the primaries and second rounds of elections being postponed too.

Dominican Republic

On April 13, 2020, the electoral body of Dominican Republic decided to postpone the presidential and legislative elections which were originally scheduled for May 17 of the same year. The new selected date was July 5, 2020, and, in case none of the presidential candidates reached the absolute majority (50% + 1 vote), the second round will be held on July 26.[232]

The general election to elect the President and members of the Dominican Republic Congress, which was postponed from the scheduled May 17, 2020 date due to the COVID-19 pandemic, was later held on July 5, 2020.[233][234]

Ethiopia

On 31 March, the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia delayed the House of Representatives elections that were originally scheduled for 29 August, due to the outbreak of coronavirus in Ethiopia.[235]

France

President Emmanuel Macron declared coronavirus as the "biggest health crisis in a century". On 12 March he stated that the first round of local elections would not be rescheduled.[236] The choice to maintain the elections, which took place on 15 March, generated significant controversy.[237] On 16 March, he stated that the second round, originally scheduled for 22 March, would be delayed until 21 June.[238]

Hong Kong

The 2020 Hong Kong Legislative Council election was originally scheduled on 6 September 2020 until it was postponed by the government for a whole year to 5 September 2021. On 31 July 2020, Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced that she was invoking the Emergency Regulations Ordinance to postpone the election under its emergency powers, citing the recent resurgence of the COVID-19 cases, adding that the move was supported by Beijing.[239]

Indonesia

The 2020 Indonesian local elections were scheduled to be held on 23 September was postponed, and the Indonesian General Elections Commission proposed postponement to 9 December at the earliest, which was then approved by the People's Representative Council and then signed into law by President Joko Widodo on 5 May. The election's previous budget of around US$550 million was reallocated towards pandemic management and control.[240][241]

Italy

A referendum on a constitutional amendment to decrease the number of members of parliament from 630 to 400 in the Chamber and from 315 to 200 in the Senate was initially scheduled to be held on 29 March, but was postponed to 20 and 21 September following the outbreak of the virus in Italy.[242] [243]

Kiribati

The first round of the parliamentary elections was originally planned to be held on 7 April 2020, but was later moved to 15 April, with the second round planned for the next week due to the coronavirus pandemic although there were no cases in the country at the time.[244][245]

Latvia

On 6 April 2020, Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš announced the government's decision to postpone the snap Riga City Council elections. Originally, the snap elections were scheduled for 25 April, and election posters had already started appearing, but as the COVID-19 crisis broke out, the elections were rescheduled for 6 June, without ruling out a possibility to move the election date closer to the fall, reported the LETA newswire. Krišjānis Kariņš said: "Considering the uncertainty regarding the COVID-19 crisis, most probably, we will move the elections to the beginning of September."[246] The elections were eventually held on August 29, 2020.[247]

New Zealand

On 17 August 2020, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced that the upcoming election would be delayed by almost 4 weeks from September 19 to October 17. The country's biggest city, Auckland, had seen a recent rise in cases of COVID-19 and was placed on a restrictive 3 week lockdown. Due to safety concerns and an inability for political parties to campaign properly, Ardern agreed to a call from opposition and government parties to delay the election.

Philippines

On 10 March 2020, the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) suspended nationwide voter registration until the end of the month due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The registration period began 20 January and is scheduled to run until 30 September 2021.[248] The suspension was later extended to last until the end of April. The issuance of voter's certification is also suspended until further notice. The next nationwide elections scheduled in the Philippines is in May 2022.[249]

The plebiscite to ratify legislation which proposes the partition of Palawan into three smaller provinces scheduled for May 2020 may be delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The province provincial legislature has called for a special session and is expected to pass a resolution allowing their governor to ask the COMELEC to postpone the plebiscite.[250]

Poland

Initially the Polish government chose to not delay the presidential election, a decision which caused controversy.[251] Polling has shown 78% of the population to prefer postponing the election.[251] The opposition to the ruling party Law and Justice has argued that the pandemic conditions prevent effective campaigning, and hence reduce the competitiveness of the election.[251] On 27 March, some candidates for the presidential election failed to collect 100,000 signatures due to the coronavirus pandemic with only twelve presidential candidates having successfully collected over 100,000 signatures. Seven candidates submitted petitions with less than 100,000 signatures, but plan to appeal the central election commission's refusal to register them in the presidential election citing the coronavirus pandemic hampering the signature collection process.[252]

A change to Poland's election laws was proposed to allow postal voting for those over 60 and those under quarantine but not abroad, which was criticized as favoring the incumbent Law and Justice Party.[253] Laws under discussion by parliament in mid-April define the entire vote to be postal and weaken the role of the electoral commission, despite postal workers unions saying this would be impossible.[251]

On 6 May, the Polish governing coalition announced the presidential election would be postponed due to the pandemic.[254] On 3 June 2020 Marshal of the Sejm Elżbieta Witek announced that first round of the delayed election would occur on 28 June 2020, with 12 July 2020 scheduled for the runoff, if it is necessary.[255]

Russia

On 25 March, President Vladimir Putin announced the postponement of the constitutional referendum scheduled for 22 April to a later date. At the moment, a new date for the referendum has not yet been determined.[256]

Also, the Central Election Commission postponed about a hundred local elections scheduled for the period from 29 March to 21 June.[257]

Regional elections in more than 20 regions are due to be held on a "single election day" on 13 September. However, the campaign must start no later than 15 June. According to media reports, depending on the epidemiological situation, the Federal government allows the postponement of a single election day to December 2020 or the holding of these regional elections on a 2021 single election day.[258]

Serbia

On 16 March 2020, the electoral commission postponed the parliamentary election that was initially planned for 26 April.[259]

Singapore

The 2020 Singaporean general election was held on 10 July 2020. The Elections Department had rolled out a series of measures in response to the pandemic to ensure that the elections can be held. No rallies and TV screenings pertaining to the election are to be held. Nomination centres will not admit members of the public and walkabouts, though allowed, should have safe distancing and minimal physical contact. Candidates are also not be allowed to make speeches, including during the campaigning, from campaigning vehicles, meaning that there will be no parades by the candidates held post-election.[260]

Spain

The 2020 Basque regional election, scheduled for 5 April, were delayed, after an agreement between all the political parties represented in the Basque parliament; the Galician elections were also suspended.[261][262]

Sri Lanka

On 19 March, Election Commissioner Mahinda Deshapriya announced that the 2020 Sri Lankan parliamentary election will be postponed indefinitely until further notice due to the coronavirus pandemic.[263][264] Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa initially insisted that scheduled forthcoming the election would proceed as planned on 25 April despite the coronavirus pandemic, and the authorities banned election rallies and meetings.[265]

Syria

The parliamentary elections originally scheduled for 13 April were delayed to 20 May to protect Syria from coronavirus.[266]

Trinidad and Tobago

The general election originally scheduled for September might be delayed but "will be held when constitutionally due" despite the coronavirus.[267] Pre-campaigning was partially suspended on 13 March following news of the first reported case of COVID-19 in Trinidad and Tobago.[268][269]

United Kingdom

On 13 March 2020, the United Kingdom local elections that were meant to be held on 7 May were rescheduled by Prime Minister Boris Johnson to 6 May 2021 following the advice of the Electoral Commission and in agreement with Labour and the Liberal Democrats.[270]

On 27 March, the Liberal Democrats postponed their leadership election, at first to May 2021, before moving it back to July 2020.[271]

United States

Presidential

Campaign

Political campaigns switched to online and virtual activities in mid-March to either avoid the spreading of coronavirus or to be in compliance with statewide social distancing rules.[272] Former Vice President Joe Biden and Senator Bernie Sanders started giving online town halls and virtual fundraisers.[273] President Donald Trump's presidential campaign also shifted from in-person to virtual campaigning due to stay-at-home orders and social distancing rules made after his 2 March rally and both his and other Republican leadership offices based in Virginia were closed due to stay-at-home orders issued by Governor Ralph Northam.[274]

On 15 March, the first one-on-one debate of the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries took place between Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders in CNN's Washington, D.C. studios and without an audience, as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The debate was moved from Arizona, which is under a state of emergency and had 12 confirmed cases of COVID-19 on that date.[275][276]

On 2 April, the Democratic National Convention, which was originally scheduled to be held from 13 to 16 July, was delayed to the week of 17 August after the Democratic National Committee communicated with the presidential campaigns of Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders.[277] On 5 April Biden suggested "a virtual convention" may be necessary;[278] Trump told Fox News' Sean Hannity there was "no way" he would cancel the Republican National convention, scheduled to begin on 24 August in Charlotte, NC.[279]

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) expressed concern in early April that the pandemic might lower voter turnout in November. Closings of churches, universities, and driver's license centers will make it more difficult for voters to register and the Democracy Project at the Brennan Center for Justice expect turnout to be low, as it was during the 17 March Illinois Democratic primary. Georgia state House Speaker David Ralston (R), predicted that mailing absentee ballot request forms to all voters in the state during the coronavirus crisis would be "devastating" for GOP candidates, and President Trump said that some of the election reforms would make it harder for Republicans to win office.[280]

There have been calls to postpone the 2020 U.S. presidential election to 2021, but many constitutional scholars, lawmakers have said it would be very difficult to do without amending the Constitution.[281][282][283]

Primaries

On 12 March 2020, the North Dakota Democratic-NPL cancelled its state convention that was meant to be held from 19 to 22 March where statewide candidates would have been nominated and delegates to the Democratic National Convention would have been selected.[284] On 13 March, the presidential primary in Louisiana was postponed to 20 June by Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin and Wyoming had its in-person portion of its caucus and all county conventions suspended and replaced with mail-in ballots.[285][286]

On 14 March, the presidential primary in Georgia was moved from 24 March to 19 May;[287] on 9 April, the entire primary was again moved to 9 June.[288] On 16 March, Secretary of State Michael Adams announced that the Kentucky primaries would be moved from 19 May to 23 June and Governor Mike DeWine postponed the Ohio primaries despite legal challenges.[289][290] On 19 March, Governor Ned Lamont moved the Connecticut Democratic primary from 28 April to 2 June.[291] On 20 March, Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb, Secretary of State Connie Lawson, Republican state chairman Kyle Hupfer, and Democratic state chairman John Zody announced that Indiana's primaries were rescheduled from 5 May to 2 June.[292]

On 21 March, Governor Wanda Vázquez Garced postponed the Puerto Rico presidential primary from 29 March to 26 April. The Alaska Democratic Party canceled in-person voting for its presidential primary and extended its mail-in voting time to 10 April. Governor John Carney postponed the Delaware presidential primary from 28 April to 2 June. The Democratic Party of Hawaii canceled in-person voting for its presidential primary and delayed it from 4 April to sometime in May. Governor Gina Raimondo postponed the Rhode Island presidential primary at the request of the board of elections from 28 April to 2 June.[293] On 27 March, Governor Tom Wolf signed into law legislation passed by the state legislature to postpone Pennsylvania's primaries from 28 April to 2 June.[294] On 28 March, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced at a news conference that New York's presidential primary would be postponed from 28 April to 23 June.[295] On 8 April, Governor Phil Murphy signed an executive order to reschedule the primary election scheduled to be held on 2 June to 7 July.[296]

On 30 March, the Kansas Democratic Party announced that its presidential primary would be conducted only through mail-in ballots, and Governor Brad Little and Secretary of State Lawerence Denney also announced that Idaho's primary elections would also be conducted entirety through mail-in ballots.[297][298] On 1 April, Governor Jim Justice signed an executive order to postpone West Virginia's primaries from 12 May to 9 June.[299]

Polling places in Florida, Ohio, Illinois and Arizona that were located in senior living facilities were moved and other health precautions were enacted.[300] Local election directors in Maryland asked for the state's primary to be changed to only use mail-in ballots and former Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Mary J. Miller asked for Governor Larry Hogan to switch to mail-in ballots.[301]

| State | Original date | New date |

|---|---|---|

| Puerto Rico | 29 March 2020 | 26 April 2020 |

| Georgia | 24 March 2020 | 9 June 2020 |

| Connecticut | 28 April 2020 | 2 June 2020 |

| Delaware | 28 April 2020 | 2 June 2020 |

| Ohio | 17 March 2020 | 2 June 2020 |

| Pennsylvania | 28 April 2020 | 2 June 2020 |

| Rhode Island | 28 April 2020 | 2 June 2020 |

| Indiana | 5 May 2020 | 2 June 2020 |

| West Virginia | 12 May 2020 | 9 June 2020 |

| Louisiana | 4 April 2020 | 20 June 2020 |

| Kentucky | 19 May 2020 | 23 June 2020 |

| New York | 28 April 2020 | 23 June 2020 |

| New Jersey | 2 June 2020 | 7 July 2020 |

Campaign

Thirty-four Democratic and Republican candidates in New York signed a petition asking Governor Andrew Cuomo for the primary petition signature amounts to be decreased or eliminated for the primaries to prevent spreading or contracting the virus during signature collection.[302] On 14 March, Cuomo reduced the signature requirement to 30% of the normal limit and moved the deadline from 2 April to 17 March.[303]

On 26 March, the Green Party said the pandemic would prevent third party candidates from appearing on the ballot unless petitioning requirements were reduced.[304]

Elections

.jpg.webp)

On 11 March 2020, the Michigan Democratic Party cancelled its state convention which was scheduled for 21 March.[305] The Utah Republican, and Democratic parties cancelled their in-person state conventions and the United Utah replaced their caucuses and conventions with virtual meetings.[306]

On 16 March, Texas Governor Greg Abbott announced the postponement of the Texas state Senate District 14 special election from 2 May to 14 July.[307] On 20 March, the North Carolina State Board of Elections announced that the Republican primary runoff for North Carolina's 11th Congressional district would be delayed to 23 June and Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves announced that the Republican primary runoff for the 2nd congressional district would be postponed to 23 June.[308][309] On 23 March, special elections for the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate were postponed.[310]

On 15 March, South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster delayed all county and municipal elections in March and April to after 1 May.[311] On 18 March, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey delayed the state's primary runoffs from 31 March to 14 July, Missouri Governor Mike Parson delayed local elections from 7 April to 2 June, and Secretary of State Paul Ziriax announced that municipalities could reschedule elections from 7 April to a late date.[312][313][314] On 24 March, Secretary of State Barbara Cegavske and Nevada's seventeen county election officials announced that Nevada's June primaries would be conducted entirely through mail-in ballots.[315] Secretary of State Paul Pate increased the absentee voting period for Iowa's June primaries and also postponed special elections in three counties.[316][317]

Wisconsin

In Wisconsin, a swing state with a Democratic governor and a Republican legislature, an April 7 election for a state Supreme Court seat, the federal presidential primaries for both the Democratic and Republican parties, and several other judicial and local elections went ahead as scheduled. Due to the pandemic, at least fifteen other U.S. states cancelled or postponed scheduled elections or primaries at the time of Wisconsin's election.[318] With Wisconsin grappling with their own pandemic, state Democratic lawmakers made several attempts to postpone their election, but were prevented by other Republican legislators. Governor Tony Evers called the Wisconsin legislature into a 4 April special session, but the Republican-controlled Assembly and Senate graveled their sessions in and out within seventeen seconds.[319] In a joint statement afterwards, Wisconsin's state Assembly Speaker Robin Vos and Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald criticized Evers for attempting to postpone the election, for not calling a special session earlier, and for reversing his previous position on keeping the election date intact.[320]

On 6 April, Evers attempted to move the election by an executive order, but was blocked by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. On the same day, a separate effort to extend the deadline for mailing absentee ballots was blocked by the Supreme Court of the United States. The only major concession achieved was that absentee ballots postmarked by 7 April at 8 p.m. would be accepted until 13 April.[321] However, local media outlets reported that many voters had not received their requested absentee ballots by election day or, due to social distancing, were unable to satisfy a legal requirement that they obtain a witness' signature.[322][323]

Lawmakers' decision to not delay the election was sharply criticized by the editorial board of the local Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, which had previously endorsed the Republican former governor Scott Walker.[324] They called the election "the most undemocratic in the state's history."[325] The New York Times characterized the election as "almost certain to be tarred as illegitimate," adding that the inability of the state's lawmakers to come to an agreement on moving the election was "an epic and predictable failure." The newspaper placed the political maneuvering as part of another chapter in "a decade of bitter partisan wrangling that saw [state Republicans] clinically attack and defang the state's Democratic institutions, starting with organized labor and continuing with voting laws making it far harder for poor and black residents of urban areas to vote."[326] Republicans believed that holding the election on 7 April, when Democratic-leaning urban areas were hard-hit by the pandemic, would help secure them political advantages like a continued 5–2 conservative majority on the Wisconsin Supreme Court (through the elected seat of Daniel Kelly).[324][327]

When the election went ahead on 7 April, access to easy in-person voting heavily depended on where voters were located. In smaller or more rural communities, which tend to be whiter and vote Republican, few issues were reported.[327][328] In more urbanized areas, the pandemic forced the closure and consolidation of many polling places around the state despite the use of 2,500 National Guard members to combat a severe shortage in poll workers.[329][330] The effects were felt most heavily in Milwaukee, the state's largest city with the largest minority population and the center of the state's ongoing pandemic.[327] The city's government was only able to open 5 of 180 polling stations after being short by nearly 1,000 poll workers.[330] As a result, lengthy lines were reported, with some voters waiting for up to 2.5 hours and through rain showers.[329][331] The lines disproportionately affected Milwaukee's large Hispanic and African-American population; the latter had already been disproportionately afflicted with the pandemic, forming nearly half of Wisconsin's documented cases and over half its deaths at the time the vote was conducted.[326][328] However, by the time the election concluded, Milwaukee Election Commissioner Neil Albrecht said that despite some of the problems, the in-person voting ran smoothly.[332]

Similar problems with poll station closures and long lines were reported in Waukesha, where only one polling station was opened for a city of 70,000, and Green Bay, where only 17 poll workers out of 270 were able to work.[326] Other cities were able to keep lines much shorter, including the state capital of Madison, which opened about two-thirds of its usual polling locations, and Appleton, which opened all of its usual 15.[329][333]

Voters across the state were advised to maintain social distancing, wear face masks, and bring their own pens.[334] Vos, the state Assembly Speaker, served as an election inspector for in-person voting on 7 April. While wearing medical-like personal protective equipment, he told reporters that it was "incredibly safe to go out" and vote, adding that voters faced "minimal exposure."[327][335]

Venezuela

The Committee of Electoral Candidacies, in charge of appointing a new National Electoral Council of Venezuela (CNE), announced that it would suspend its meetings until further notice because of the pandemic.[336]

Impact on politicians and public figures

Armenia

On 1 June 2020, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinian and his family were infected with COVID-19.[337]

On 20 November 2020, former first lady Rita Sargsyan died from COVID-19 at the age of 58.[338]

Australia

On 13 March 2020, Peter Dutton, the Minister for Home Affairs, stated that he was infected with COVID-19 and went into isolation in a hospital after having attended a Five Eyes security pact in Washington, D.C. where he met with United States President Donald Trump, United States Attorney General William Barr, and Ivanka Trump.[339]

Austria

On 17 October 2020, the Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg tested positive for the coronavirus.[340] On 29 November 2020, the Defense Minister Klaudia Tanner tested positive for the coronavirus.[341]

Belgium

On 17 October 2020, the Foreign Minister Sophie Wilmès tested positive for the coronavirus.[340]

Bulgaria

On 25 October 2020, the Prime Minister Boyko Borisov, stated that he was infected with COVID-19.[342] Krasen Kralev, the country's Minister of Youth and Sports, had previously tested positive for the virus on August 23.[343]

Burundi

President of Burundi Pierre Nkurunziza died on 8 June 2020 of a heart attack at age 55 and was later reported to have tested positive for COVID-19.[344] He is the first world leader to have died with the disease.[345] The country's former President Pierre Buyoya also died on December 17 in Paris, where he had been flown for medical treatment after testing positive for the virus.[346]

Canada

On 12 March 2020, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his wife Sophie Grégoire Trudeau went into isolation while Sophie underwent testing that later showed that she tested positive for COVID-19.[347]

On 25 March, the liberal MP from Brampton West, Kamal Khera, announced that she has tested positive for COVID-19 and would be self-isolating. She was the first federal politician to test positive.[348]

Croatia

On 30 November 2020, Andrej Plenković, the Prime Minister, stated that he was infected with COVID-19.[349]

Several other government ministers have also tested positive for the virus during the course of the pandemic, including Justice Minister Ivan Malenica on 21 July, Tourism Minister Nikolina Brnjac on 26 October and Health Minister Vili Beroš on November 19.[350][351][352]

Czech Republic

On 18 October 2020, Miroslav Toman, the Minister of Agriculture, stated that he was infected with COVID-19, after a meeting where he met with Czech President Milos Zeman.[353] On 19 October 2020, Martin Nejedlý, the Advisor to the President, stated that he was infected with COVID-19.[354]

France

In March 2020 it was reported that 4 MPs had tested positive; Jean-Luc Reitzer, Sylvie Tolmont, Élisabeth Toutut-Picard and Guillaume Vuilletet.[355]

On 17 December, President Emmanuel Macron tested positive for COVID-19.[356]

Georgia

On 2 November 2020, Giorgi Gakharia, the Prime Minister, stated that he was infected with COVID-19.[357]

Germany

On 28 March 2020, Hesse Finance Minister Thomas Schäfer committed suicide as he believed that he could not meet the financial aid expectations to combat the coronavirus pandemic.[358] On 21 October 2020, Jens Spahn, the Health Minister, stated that he was infected with COVID-19[359]

Honduras

President Juan Orlando Hernandez and his wife Ana Garcia test positive. [360]

Hungary

On 20 October 2020, Judit Varga, the Justice Minister, stated that he was infected with COVID-19.[361] On 4 November, the Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó tested positive for the virus during an official visit to Thailand and was flown home.[362]

Ireland

President of Sinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald was the first high-profile Irish politician affected by the spread of COVID-19, with her party cancelling events and her family entering self-isolation for a period, after McDonald confirmed on 2 March that her children attended the same school as the student with the first recorded case of COVID-19 in Ireland.[363] On 16 March, Thomas Pringle, an independent TD representing the Donegal constituency, entered isolation due to previous contact with someone in Dublin and the high risk to his own personal health.[364][365]

On 18 March, Luke 'Ming' Flanagan, the independent MEP representing the Midlands–North-West constituency, announced that he and his family would begin self-isolating after his daughter exhibited symptoms of COVID-19.[366]

On 21 August, it was announced that Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine Dara Calleary and Seanad Leas-Chathaoirleach Jerry Buttimer resigned after they attended an Oireachtas Golf Society event which contravened regulations under the Health Act.[367][368] The resulting scandal became known as Golfgate. European Commissioner for Trade Phil Hogan who also attended the dinner, resigned on 26 August 2020.

Leo Varadkar, the Tánaiste, re-registered as a doctor in 2020 to assist with the COVID effort.[369]

Italy

On 7 March 2020, Nicola Zingaretti, the Secretary of the Democratic Party and President of Lazio, announced that he was infected with COVID-19 and Anna Ascani, vice minister of Education, also stated that she was infected by the virus on 14 March.[370][371]

On 4 September 2020, Italy's former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi was hospitalized after positive coronavirus.[372] "It has been the most dangerous test of my life," Berlusconi told reporters after leaving the hospital, adding that he "dodged a bullet once again." [373]

On 5 October 2020, former Health Minister Beatrice Lorenzin announced that she was infected with COVID-19.[374]

On 16 October 2020, Mariastella Gelmini, a prominent member of Forza Italia, announced that she was infected with COVID-19.[375]

Other positives includes: Alberto Cirio, governor of Piemonte; Pier Paolo Sileri, vice minister of Health; Andrea Orlando, vice secretary of Partito Democratico; Stefano Bonaccini, governor of Emilia Romagna; Rocco Casalino, spokesman of the prime minister Giuseppe Conte; Virginia Raggi, mayor of Rome.[376][377][378]

Libya