Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment

The worldwide disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in numerous effects on the environment and climate. The global reduction in modern human activity such as the considerable decline in planned travel was coined anthropause and has caused a large drop in air pollution and water pollution in many regions.[2][3][4] In China, lockdowns and other measures resulted in a 25 percent reduction in carbon emissions and 50 percent reduction in nitrogen oxides emissions, which one Earth systems scientist estimated may have saved at least 77,000 lives over two months.[5][6][7][8] Other positive effects on the environment include governance-system-controlled investments towards a sustainable energy transition and other goals related to environmental protection such as the European Union's seven-year €1 trillion budget proposal and €750 billion recovery plan "Next Generation EU" which seeks to reserve 25% of EU spending for climate-friendly expenditure.[9][10][11]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

However, the pandemic has also provided cover for illegal activities such as deforestation of the Amazon rainforest and poaching in Africa, hindered environmental diplomacy efforts, and created economic fallout that some predict will slow investment in green energy technologies.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Background

Up to 2020, increase in the amount of greenhouse gases produced since the beginning of the industrialization era caused average global temperatures on the Earth to rise, causing effects including the melting of glaciers and rising sea levels.[18][19][20]

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, measures that were expected to be recommended to health authorities in the case of a pandemic included quarantines and social distancing.[21]

Independently, also prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers argued that reduced economic activity would help decrease global warming as well as air and marine pollution, allowing the environment to slowly flourish.[22][23] This effect has been observed following past pandemics in 14th century Eurasia and 16th-17th century North and South America.[24]

Researchers and officials have also called for biodiversity protections to form part of COVID-19 recovery strategies.[25][26]

Air quality

Due to the pandemic's impact on travel and industry, many regions and the planet as a whole experienced a drop in air pollution.[5][27][28] Reducing air pollution can reduce both climate change and COVID-19 risks[29] but it is not yet clear which types of air pollution (if any) are common risks to both climate change and COVID-19. The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air reported that methods to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2, such as quarantines and travel bans, resulted in a 25 percent reduction of carbon emission in China.[6][8] In the first month of lockdowns, China produced approximately 200 million fewer metric tons of carbon dioxide than the same period in 2019, due to the reduction in air traffic, oil refining, and coal consumption.[8] One Earth systems scientist estimated that this reduction may have saved at least 77,000 lives.[8] However, Sarah Ladislaw from the Center for Strategic & International Studies argued that reductions in emissions due to economic downturns should not be seen as beneficial, stating that China's attempts to return to previous rates of growth amidst trade wars and supply chain disruptions in the energy market will worsen its environmental impact.[30] Between 1 January and 11 March 2020, the European Space Agency observed a marked decline in nitrous oxide emissions from cars, power plants, and factories in the Po Valley region in northern Italy, coinciding with lockdowns in the region.[31] From areas in North India such as Jalandhar, the Himalayas became visible again for the first time in decades, as air quality improved due to the drop in pollution.[32][33]

.jpg.webp)

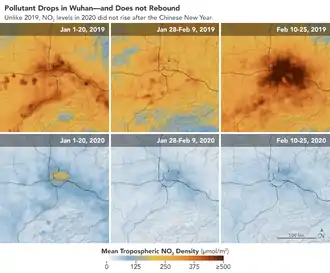

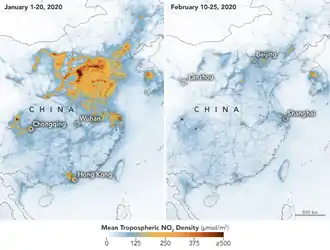

NASA and ESA have been monitoring how the nitrogen dioxide gases dropped significantly during the initial Chinese phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The economic slowdown from the virus drastically dropped pollution levels, especially in cities like Wuhan, China by 25-40%.[5][34][35] NASA uses an ozone monitoring instrument (OMI) to analyze and observe the ozone layer and pollutants such as NO2, aerosols and others. This instrument helped NASA to process and interpret the data coming in due to the lock-downs worldwide.[36] According to NASA scientists, the drop in NO2 pollution began in Wuhan, China and slowly spread to the rest of the world. The drop was also very drastic because the virus coincided with the same time of year as the lunar year celebrations in China.[5] During this festival, factories and businesses were closed for the last week of January to celebrate the lunar year festival.[37] The drop in NO2 in China did not achieve an air quality of the standard considered acceptable by health authorities. Other pollutants in the air such as aerosol emissions remained.[38]

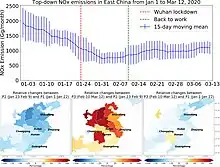

A joint research led by scientists from China and U.S. estimated that nitrogen oxides (NOx=NO+NO2) emissions decreased by 50% in East China from 23 January (Wuhan lockdown) to 9 February 2020 in comparison to the period from 1 to 22 January 2020.[5] Emissions then increased by 26% from 10 February (back-to-work day) to 12 March 2020, indicating possible increasing socioeconomic activities after most provinces allowed businesses to open.[5] It is yet to be investigated what COVID-19 control measures are most efficient controlling virus spread and least socioeconomic impact.[5]

Water quality

Peru

The Peruvian jungle experienced 14 oil spills from the beginning of the pandemic through early October 2020. Of these, eight spills were in a single sector operated by Frontera Energy del Perú S.A. which ceased operations during the pandemic and is not maintaining its wells and pipes. The oil seeps into the ground where it contaminates the drinking water of indigenous people in Quichua territory.[39]

Italy

In Venice, shortly after quarantine began in March and April 2020, water in the canals cleared and experienced greater water flow.[40] The increase in water clarity was due to the settling of sediment that is disturbed by boat traffic and mentioned the decrease in air pollution along the waterways.[41]

Wildlife

Fish prices and demand for fish have decreased due to the pandemic,[42] and fishing fleets around the world sit mostly idle.[43] German scientist Rainer Froese has said the fish biomass will increase due to the sharp decline in fishing, and projected that in European waters, some fish such as herring could double their biomass.[42] As of April 2020, signs of aquatic recovery remain mostly anecdotal.[44]

As people stayed at home due to lockdown and travel restrictions, some animals have been spotted in cities. Sea turtles were spotted laying eggs on beaches they once avoided (such as the coast of the Bay of Bengal), due to the lowered levels of human interference and light pollution.[45] In the United States, fatal vehicle collisions with animals such as deer, elk, moose, bears, mountain lions fell by 58% during March and April.[46]

Conservationists expect that African countries will experience a massive surge in bush meat poaching. Matt Brown of the Nature Conservancy said that "When people don't have any other alternative for income, our prediction -- and we're seeing this in South Africa -- is that poaching will go up for high-value products like rhino horn and ivory."[12][13] On the other hand, Gabon decided to ban the human consumption of bats and pangolins, to stem the spread of zoonotic diseases, as SARS-CoV-2 is thought to have transmitted itself to humans through these animals.[47] In June 2020, Myanmar allowed breeding of endangered animals such as tigers, pangolins, and elephants. Experts fear that the Southeast Asian country's attempts to deregulate wildlife hunting and breeding may create "a New Covid-19."[48]

Deforestation and reforestation

The disruption from the pandemic provided cover for illegal deforestation operations. This was observed in Brazil, where satellite imagery showed deforestation of the Amazon rainforest surging by over 50 percent compared to baseline levels.[15][16] Unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic facilitated the recruitment of labourers for Pakistan's 10 Billion Tree Tsunami campaign to plant 10 billion trees – the estimated global annual net loss of trees[49] – over the span of 5 years.[50][51]

Carbon emissions

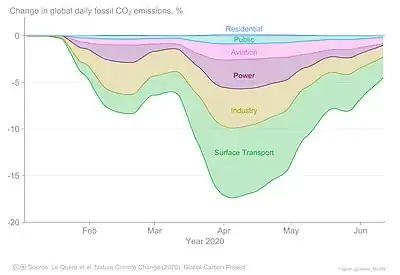

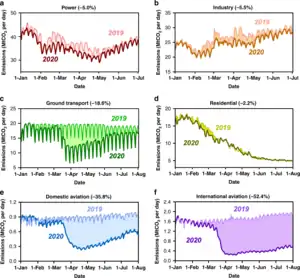

A study published in May 2020 found that the daily global carbon emissions during the lockdown measures in early April fell by 17% and could lead to an annual carbon emissions decline of up to 7%, which would be the biggest drop since World War II according to the researchers. They ascribe these decreases mainly to the reduction of transportation usage and industrial activities.[53][54] However, it has been noted that rebounding could diminish reductions due to the more limited industrial activities.[55] Nevertheless, societal shifts caused by the COVID-19 lockdowns – like widespread telecommuting, adoption of remote work policies,[56][57] and the use of virtual conference technology – may have a more sustained impact beyond the short-term reduction of transportation usage.[55][58] In a study published in September 2020, scientists estimate that such behavioral changes developed during confinement may reduce 15% of all transportation CO₂ emissions permanently.[59]

Despite this, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was the highest ever recorded in human history in May 2020.[60] Energy and climate expert Constantine Samaras states that "a pandemic is the worst possible way to reduce emissions" and that "technological, behavioural, and structural change is the best and only way to reduce emissions".[60] Tsinghua University's Zhu Liu clarifies that "only when we would reduce our emissions even more than this for longer would we be able to see the decline in concentrations in the atmosphere".[60] The world's demand for fossil fuels has decreased by almost 10% amid COVID-19 measures and reportedly many energy economists believe it may not recover from the crisis.[61]

In a study published in August 2020, scientists estimate that global NOx emissions declined by as much as 30% in April but were offset by ~20% reduction in global SO₂ emissions that weakens the cooling effect and conclude that the direct effect of the response to the pandemic on global warming will likely be negligible, with an estimated cooling of around 0.01 ±0.005 °C by 2030 compared to a baseline scenario but that indirect effects due to an economic recovery tailored towards stimulating a green economy, such as by reducing fossil fuel investments, could avoid future warming of 0.3 °C by 2050.[62][63] The study indicates that systemic change in how humanity powers and feeds itself is required for a substantial impact on global warming.[62]

In October 2020 scientists reported, based on near-real-time activity data, an 'unprecedented' abrupt 8.8% decrease in global CO₂ emissions in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, larger than during previous economic downturns and World War II. Authors note that such decreases of human activities "cannot be the answer" and that structural and transformational changes in human economic management and behaviour systems are needed.[64][52]

Fossil fuel industry

A report by the London-based think tank Carbon Tracker concludes that the COVID-19 pandemic may have pushed the fossil fuel industry into "terminal decline" as demand for oil and gas decreases while governments aim to accelerate the clean energy transition. It predicts that an annual 2% decline in demand for fossil fuels could cause the future profits of oil, gas and coal companies to collapse from an estimated $39tn to $14tn.[65][61] However, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance more than half a trillion dollars worldwide are currently intended to be poured into high-carbon industries.[66] Preliminary disclosures from the Bank of England's Covid Corporate Financing Facility indicate that billions of pounds of taxpayer support are intended to be funneled to fossil fuel companies.[66] According to Reclaim Finance the European Central Bank intends to allocate as much as €220bn (£193bn) to fossil fuel industries.[66] An assessment by Ernst & Young finds that a stimulus program that focuses on renewable energy and climate-friendly projects could create more than 100,000 direct jobs across Australia and estimates that every $1m spent on renewable energy and exports creates 4.8 full-time jobs in renewable infrastructure while $1m on fossil fuel projects would only create 1.7 full-time jobs.[67]

In addition, also due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry, natural gas prices have dropped so low that gas producers were burning if off on-site (not being worth the cost to transport it to cracking facilities). Bans on single-use consumer plastic (in China, the European Union, Canada, and many countries in Africa), and bans on plastic bags (in several states in the USA) have also reduced demand for plastics considerably. Many cracking facilities in the USA have been suspended. The petrochemical industry has been trying to save itself by attempting to rapidly expand demand for plastic products worldwide (i.e. through pushbacks on plastic bans and by increasing the number of products wrapped in plastic in countries where plastic use is not already as widespread (i.e. developing nations)).[68]

Cycling

During the pandemic many people have started cycling[69] and bike sales surged.[70][71][72][73][74] Many cities set up semi-permanent "pop-up bike lanes" to provide people who switch from public transit to bicycles with more room.[75][76][77][78] In Berlin proposals exist to make the initially reversible changes permanent.[79][80][81][82][83]

Retail and food production

Small-scale farmers have been embracing digital technologies as a way to directly sell produce, and community-supported agriculture and direct-sell delivery systems are on the rise.[84] These methods have benefited smaller online grocery stores which predominantly sell organic and more local food and can have a positive environmental impact due to consumers who prefer to receive deliveries rather than travel to the store by car.[85] Online grocery shopping has grown substantially during the pandemic.[86]

While carbon emissions dropped during the pandemic, methane emissions from livestock continued to rise. Methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.[87]

Litter

As a consequence of the unprecedented use of disposable face masks, a significant number of masks were discarded in the natural environment, adding to the worldwide burden of plastic waste.[88] During the COVID-19 pandemic, plastics demand for medical usage has increased considerably in some countries. Besides personal protective equipment (PPE) such as masks and gloves, a considerable increase in plastic usage has been related to requirements packaging, and single-use items. Collectively, these shifts in hospitals and regular life may exacerbate environmental issues with plastics, which already existed even before the pandemic occurred.[89]

Investments and other economic measures

Some have noted that planned stimulus package could be designed to speed up renewable energy transitions and to boost energy resilience.[55] Researchers of the World Resources Institute have outlined a number of reasons for investments in public transport as well as cycling and walking during and after the pandemic.[90] Use of public transport in cities worldwide has fallen by 50-90%, with substantial loss of revenue losses for operators. Investments such as in heightened hygienic practices on public transport and in appropriate social distancing measures may address public health concerns about public transport usage.[91] The International Energy Agency states that support from governments due to the pandemic could drive rapid growth in battery and hydrogen technology, reduce reliance on fossil fuels and has illustrated the vulnerability of fossil fuels to storage and distribution problems.[92][93][94]

According to a study published in August 2020, an economic recovery "tilted towards green stimulus and reductions in fossil fuel investments" could avoid future warming of 0.3 °C by 2050.[63]

Secretary-general of the OECD club of rich countries José Ángel Gurría, called upon countries to "seize this opportunity [of the COVID-19 recovery] to reform subsidies and use public funds in a way that best benefits people and the planet".[66]

In March 2020, the ECB announced the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme.[95] Reclaim Finance said that the Governing Council failed to integrate climate into both the “business as usual” monetary policy and the crisis response. It also ignored the call from 45 NGO's that demanded that the ECB deliver a profound shift on climate integration at this decision-making meeting[96] This, as it also finances 38 fossil fuel companies, including 10 active in coal and 4 in shale oil and gas.[97] Greenpeace stated that (by June 2020) the ECB's covid-related asset purchases already funded the fossil fuel sector by to up to 7.6 billion.[98]

With the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak spreading rapidly within the European Union, the focus on the European Green Deal diminished. Some have suggested either a yearly pause or even a complete discontinuation of the deal. Many believe the current main focus of the European Union's current policymaking process should be the immediate, shorter-term crisis rather than climate change.[99] In May 2020 the €750 billion European recovery package, called Next Generation EU,[100][101] and the €1 trillion budget were announced. The European Green deal is part of it. One of the package's principles is "Do no harm". The money will be spent only on projects that meet some green criteria. 25% of all funding will go to climate change mitigation. Fossil fuels and nuclear power are excluded from the funding.[102]

Some sources of revenue for environmental projects – such as indigenous communities monitoring rainforests and conservation projects – diminished due to the pandemic.[103]

Despite a temporary decline in global carbon emissions, the International Energy Agency warned that the economic turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may prevent or delay companies and others from investing in green energy.[17][104][105] Others cautioned that large corporations and the wealthy could exploit the crisis for economic gain in line with the Shock Doctrine, as has occurred after past pandemics.[24]

The Earth Overshoot Day took place more than three weeks later than 2019, due to COVID-19 induced lockdowns around the world.[106] The president of the Global Footprint Network claims that the pandemic by itself is one of the manifestations of "ecological imbalance".[107]

Analyses and recommendations

Multiple organizations and organization-coalitions – such as think tanks, companies, business organisations, political bodies and research institutes – have created unilateral analyses and recommendations for investments and related measures for sustainability-oriented socioeconomic recovery from the pandemic on global and national levels – including the International Energy Agency,[108][91] the Grantham Institute – Climate Change and Environment[109] and the European Commission.[110][111][112][113][114] The United Nations' Secretary General António Guterres recommended six broad sustainability-related principles for shaping the recovery.[115]

According to a report commissioned by the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy and published in July 2020, investment in four key ocean intervention areas could help aid economic recovery and yield high returns on investment in terms of economic, environmental and health benefits. According to Jackie Savitz, chief policy officer for America ocean conservation nonprofit Oceana, strategies such as "setting science-based limits on fishing so that stocks can recover, practicing selective fishing to protect endangered species and ensuring that fishing gear doesn't destroy ocean habitats are all effective, cost-efficient ways to manage sustainable fisheries".[116]

Politics

The pandemic has also impacted environmental policy and climate diplomacy, as the 2020 United Nations Climate Change Conference was postponed to 2021 in response to the pandemic after its venue was converted to a field hospital. This conference was crucial as nations were scheduled to submit enhanced nationally determined contributions to the Paris Agreement. The pandemic also limits the ability of nations, particularly developing nations with low state capacity, to submit nationally determined contributions, as they are focusing on the pandemic.[14]

Time highlighted three possible risks: that preparations for the November 2020 Glasgow conference planned to follow the 2015 Paris Agreement were disrupted; that the public would see global warming as a lower priority issue than the pandemic, weakening the pressure on politicians; and that a desire to "restart" the global economy would cause an excess in extra greenhouse gas production. However the drop in oil prices during the COVID-19 recession could be a good opportunity to get rid of fossil fuel subsidies, according to the Executive Director of the International Energy Agency.[117]

Carbon Tracker argues that China should not stimulate the economy by building planned coal-fired power stations, because many would have negative cashflow and would become stranded assets.[118]

The United States' Trump administration suspended the enforcement of some environmental protection laws via the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) during the pandemic. This allows polluters to ignore some environmental laws if they can claim that these violations were caused by the pandemic.[119]

Predicted rebound effect

The restarting of greenhouse-gas producing industries and transport following the COVID-19 lockdowns was hypothesized as an event that would contribute to increasing greenhouse gas production rather than reducing it.[120] In the transport sector, the pandemic could trigger several effects, including behavioral changes – such as more teleworking and teleconferencing and changes in business models – which could, in turn, translate in reductions of emissions from transport. A scientific study published in September 2020 estimates that sustaining such behavioral changes could abate 15% of all transport emissions with limited impacts on societal well-being.[59] On the other hand, there could be a shift away from public transport, driven by fear of contagion, and reliance on single-occupancy cars, which would significantly increase emissions.[121] However, city planners are also creating new cycle paths in some cities during the pandemic.[122] In June 2020 it was reported that carbon dioxide emissions were rebounding quickly.[123]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recommends governments continue to enforce existing air pollution regulations during the COVID-19 crisis and after the crisis, and channel financial support measures to public transport providers to enhance capacity and quality with a focus on reducing crowding and promoting cleaner facilities.[124]

Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency, states that "the next three years will determine the course of the next 30 years and beyond" and that "if we do not [take action] we will surely see a rebound in emissions. If emissions rebound, it is very difficult to see how they will be brought down in future. This is why we are urging governments to have sustainable recovery packages."[111]

Psychology and risk perception

Chaos and the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic may have made a catastrophic future seem less remote and action to prevent it more necessary and reasonable. However, it may also have the opposite effect by having minds focus on more immediate issues of the pandemic rather than ecosystem issues such as deforestation.[125]

Impact on environmental monitoring and prediction

Weather forecasts

The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) announced that a worldwide reduction in aircraft flights due to the pandemic could impact the accuracy of weather forecasts, citing commercial airlines' use of Aircraft Meteorological Data Relay (AMDAR) as an integral contribution to weather forecast accuracy. The ECMWF predicted that AMDAR coverage would decrease by 65% or more due to the drop in commercial flights.[126]

Seismic noise reduction

Seismologists have reported that quarantine, lockdown, and other measures to mitigate COVID-19 have resulted in a mean global high-frequency seismic noise reduction of 50%.[127] This study reports that the noise reduction resulted from a combination of factors including reduced traffic/transport, lower industrial activity, and weaker economic activity. The reduction in seismic noise was observed at both remote seismic monitoring stations and at borehole sensors installed several hundred metres below the ground. The study states that the reduced noise level may allow for better monitoring and detection of natural seismic sources, such as earthquakes and volcanic activity.

See also

References

- "Earth Observatory". Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Rutz, Christian; Loretto, Matthias-Claudio; Bates, Amanda E.; Davidson, Sarah C.; Duarte, Carlos M.; Jetz, Walter; Johnson, Mark; Kato, Akiko; Kays, Roland; Mueller, Thomas; Primack, Richard B. (September 2020). "COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (9): 1156–1159. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1237-z. ISSN 2397-334X.

- Team, The Visual and Data Journalism (28 March 2020). "Coronavirus: A visual guide to the pandemic". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020.

- Venter, Zander S.; Aunan, Kristin; Chowdhury, Sourangsu; Lelieveld, Jos (11 August 2020). "COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (32): 18984–18990. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006853117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 32723816. S2CID 220850924.

- Zhang, Ruixiong; Zhang, Yuzhong; Lin, Haipeng; Feng, Xu; Fu, Tzung-May; Wang, Yuhang (April 2020). "NOx Emission Reduction and Recovery during COVID-19 in East China". Atmosphere. 11 (4): 433. Bibcode:2020Atmos..11..433Z. doi:10.3390/atmos11040433. S2CID 219002558. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Myllyvirta, Lauri (19 February 2020). "Analysis: Coronavirus has temporarily reduced China's CO2 emissions by a quarter". CarbonBrief. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Burke, Marshall. "COVID-19 reduces economic activity, which reduces pollution, which saves lives". Global Food, Environment and Economic Dynamics. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- McMahon, Jeff (16 March 2020). "Study: Coronavirus Lockdown Likely Saved 77,000 Lives In China Just By Reducing Pollution". Forbes. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Simon, Frédéric (27 May 2020). "'Do no harm': EU recovery fund has green strings attached". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Carpenter, Scott. "As Europe Unveils 'Green' Recovery Package, Trans-Atlantic Rift On Climate Policy Widens". Forbes. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "France and Germany Bring European Recovery Fund Proposal to Table". South EU Summit. 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Conservationists fear African animal poaching will increase during COVID-19 pandemic". ABC News. 14 April 2020.

- "'Filthy bloody business:' Poachers kill more animals as coronavirus crushes tourism to Africa". CNBC. 24 April 2020.

- "Cop26 climate talks postponed to 2021 amid coronavirus pandemic". Climate Home News. 1 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Deforestation of Amazon rainforest accelerates amid COVID-19 pandemic". ABC News. 6 May 2020.

- "Deforestation of the Amazon has soared under cover of the coronavirus". NBC News. 11 May 2020.

- Newburger, Emma (13 March 2020). "Coronavirus could weaken climate change action and hit clean energy investment, researchers warn". CNBC. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Mishra, Anshuman. "Air Pollution". WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. WHO. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Is sea level rising?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Climate Change". National Geographic Society. 28 March 2019. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Madhav, Nita; Oppenheim, Ben; Gallivan, Mark; Mulembakani, Prime; Rubin, Edward; Wolfe, Nathan (2017), Jamison, Dean T.; Gelband, Hellen; Horton, Susan; Jha, Prabhat (eds.), "Pandemics: Risks, Impacts, and Mitigation", Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty (3rd ed.), The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1_ch17, ISBN 978-1-4648-0527-1, PMID 30212163, archived from the original on 23 March 2020, retrieved 6 April 2020

- Kopnina, Helen; Washington, Haydn; Taylor, Bron; J Piccolo, John (1 February 2018). "Anthropocentrism: More than Just a Misunderstood Problem". Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 31 (1): 109–127. doi:10.1007/s10806-018-9711-1. ISSN 1573-322X. S2CID 158116575.

- Rull, Valentí (1 September 2016). "The humanized Earth system (HES)". The Holocene. 26 (9): 1513–1516. Bibcode:2016Holoc..26.1513R. doi:10.1177/0959683616640053. hdl:10261/136857. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 131086152.

- Weitzel, Elic (2020), "Are Pandemics Good for the Environment?", Sapiens, retrieved 7 July 2020

- Pearson, Ryan M.; Sievers, Michael; McClure, Eva C.; Turschwell, Mischa P.; Connolly, Rod M. (22 May 2020). "COVID-19 recovery can benefit biodiversity". Science. 368 (6493): 838–839. Bibcode:2020Sci...368..838P. doi:10.1126/science.abc1430. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 32439784. S2CID 218836621. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Rodrigues, CM. "Letter: We call on leaders to put climate and biodiversity at the top of the agenda". Financial Times. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Watts, Jonathan; Kommenda, Niko (23 March 2020). "Coronavirus pandemic leading to huge drop in air pollution". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Le Quéré, Corinne; Jackson, Robert B.; Jones, Matthew W.; Smith, Adam J. P.; Abernethy, Sam; Andrew, Robbie M.; De-Gol, Anthony J.; Willis, David R.; Shan, Yuli; Canadell, Josep G.; Friedlingstein, Pierre (19 May 2020). "Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement". Nature Climate Change. 10 (7): 647–653. Bibcode:2020NatCC..10..647L. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0797-x. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 218693901.

- editor, Damian Carrington Environment (7 April 2020). "Air pollution linked to far higher Covid-19 death rates, study finds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "The Global Impacts of the Coronavirus Outbreak". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Green, Matthew (13 March 2020). "Air pollution clears in northern Italy after coronavirus lockdown, satellite shows". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Picheta, Rob (9 April 2020). "People in India can see the Himalayas for the first time in 'decades,' as the lockdown eases air pollution". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020.

- Brown, Vanessa. "Covid 19 Coronavirus: India's Himalayas return to view as pollution drops". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020.

- "Airborne Nitrogen Dioxide Plummets Over China". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Analysis: Coronavirus temporarily reduced China's CO2 emissions by a quarter". Carbon Brief. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "NASA Aura OMI". NASA Aura. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020.

- "Archived copy". chinesenewyear.net. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Earth Matters - How the Coronavirus Is (and Is Not) Affecting the Environment". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 5 March 2020. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Zárate, Joseph (2 October 2020). "Opinion | The Amazon Was Sick. Now It's Sicker". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- "Jellyfish seem swimming in Venice's canals". CNN. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Srikanth, Anagha (18 March 2020). "As Italy quarantines over coronavirus, swans appear in Venice canals, dolphins swim up playfully". The Hill. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Korten, Tristram (8 April 2020). "With Boats Stuck in Harbor Because of COVID-19, Will Fish Bounce Back?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Reiley, Laura (8 April 2020). "Commercial fishing industry in free fall as restaurants close, consumers hunker down and vessels tie up". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Millan Lombrana, Laura (17 April 2020). "With Fishing Fleets Tied Up, Marine Life Has a Chance to Recover". Bloomberg Green. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "While you stay home, animals roam free in our towns and cities". living. 25 April 2020.

- Katz, Cheryl (26 June 2020). "Roadkill rates fall dramatically as lockdown keeps drivers at home". National Geographic. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- EDT, Rosie McCall On 4/6/20 at 11:18 AM (6 April 2020). "Eating bats and pangolins banned in Gabon as a result of coronavirus pandemic". Newsweek. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Tiger, pangolin farming in Myanmar risks 'boosting demand'". phys.org. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Earth has 3 trillion trees but they're falling at alarming rate". Reuters. 2 September 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "As a 'green stimulus' Pakistan sets virus-idled to work planting trees". Reuters. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Pakistan Hires Thousands of Newly-Unemployed Laborers for Ambitious 10 Billion Tree-Planting Initiative". Good News Network. thegoodnewsnetwork. 30 April 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Liu, Zhu; Ciais, Philippe; Deng; Schellnhuber, Hans; et al. (14 October 2020). "Near-real-time monitoring of global CO2 emissions reveals the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5172. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18922-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7560733. PMID 33057164. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

Available under CC BY 4.0. - "Carbon emissions fall 17% worldwide under coronavirus lockdowns, study finds". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Global carbon emissions dropped 17 percent during coronavirus lockdowns, scientists say". NBC News. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Carbon emissions are falling sharply due to coronavirus. But not for long". Science. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Commentary: Coronavirus may finally force businesses to adopt workplaces of the future". Fortune. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Yaffe-Bellany, David (26 February 2020). "1,000 Workers, Go Home: Companies Act to Ward Off Coronavirus". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Viglione, Giuliana (2 June 2020). "How scientific conferences will survive the coronavirus shock". Nature. 582 (7811): 166–167. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01521-3. PMID 32488188. S2CID 219284783. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Stoll, Christian; Mehling, Michael (September 2020). "COVID-19: Clinching the Climate Opportunity". One Earth. 3 (4): 400–404. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.09.003.

- "Plunge in carbon emissions from lockdowns will not slow climate change". National Geographic. 29 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Ambrose, Jillian (3 June 2020). "Coronavirus crisis could cause $25tn fossil fuel industry collapse". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Lockdown emissions fall will have 'no effect' on climate". phys.org. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Forster, Piers M.; Forster, Harriet I.; Evans, Mat J.; Gidden, Matthew J.; Jones, Chris D.; Keller, Christoph A.; Lamboll, Robin D.; Quéré, Corinne Le; Rogelj, Joeri; Rosen, Deborah; Schleussner, Carl-Friedrich; Richardson, Thomas B.; Smith, Christopher J.; Turnock, Steven T. (7 August 2020). "Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19". Nature Climate Change: 1–7. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0883-0. ISSN 1758-6798. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "Pandemic caused 'unprecedented' emissions drop: study". phys.org. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Pandemic is triggering 'terminal decline' of fossil fuel industry, says report". The Independent. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Covid-19 relief for fossil fuel industries risks green recovery plans". the Guardian. 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Renewable energy stimulus can create three times as many Australian jobs as fossil fuels". The Guardian. 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Will Coronavirus Be the Death or Salvation of Big Plastic?". Time. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Richard Smith: How can we achieve a healthy recovery from the pandemic?". The BMJ. 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Villafranca, Omar (20 May 2020). "Americans turn to cycling during the coronavirus pandemic". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Winkelmann, Sarah. "Bike shops see surge in sales during pandemic". www.weau.com. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Earls, Stephanie. "Bike sales boom during the pandemic as more kids pedal as a pastime". Colorado Springs Gazette. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "On your bike! Coronavirus prompts cycling frenzy in Germany". DW.COM. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Lee, Edward. "Bike shops shift into higher gear as Marylanders become more active outdoors during coronavirus pandemic". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "How COVID-19 Has Caused 'Pop-Up' Bike Lanes to Appear Overnight". Discerning Cyclist. 18 April 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Oltermann, Philip (13 April 2020). "Pop-up bike lanes help with coronavirus physical distancing in Germany". Retrieved 19 January 2021 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Reid, Carlton. "Paris To Create 650 Kilometers Of Post-Lockdown Cycleways". Forbes. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Sydney gets 10km of pop-up cycleways". Government News. 18 May 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Mobilitätswende in Europa: Die Pop-up-Radwege von Berlin". www.rnd.de. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Schubert, Thomas (7 November 2020). "Pop-up-Radweg in Berlin: Erster temporärer Streifen wird dauerhaft". www.morgenpost.de. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "In Corona-Zeiten eingerichtet: Gericht: Pop-up-Radwege in Berlin dürfen vorerst bleiben". Retrieved 19 January 2021 – via www.faz.net.

- "Pop-up-Radwege in Berlin sollen vorerst bleiben". www.tagesspiegel.de. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Berlins Radverkehr boomt im Corona-Jahr". www.tagesspiegel.de. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Foote, Natasha (2 April 2020). "Innovation spurred by COVID-19 crisis highlights 'potential of small-scale farmers'".

- "Delivery disaster: the hidden environmental cost of your online shopping". the Guardian. 17 February 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus will change the grocery industry forever". CNN. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Guy, Jack (15 July 2020). "Global methane emissions are at a record high, and burping cows are driving the rise". CNN. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Discarded coronavirus masks clutter Hong Kong's beaches, trails". Hong Kong (Reuters). Reuters. 12 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "Minimising the present and future plastic waste, energy and environmental footprints related to COVID-19". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 127: 109883. 1 July 2020. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.109883 – via www.sciencedirect.com.

- "Safer, More Sustainable Transport in a Post-COVID-19 World". World Resources Institute. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Transport – Sustainable Recovery – Analysis - IEA". IEA. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "World has 'historic' opportunity for green tech boost, says global watchdog". Reuters. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Green hydrogen's time has come, say advocates eying post-pandemic world". Reuters. 8 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Farmbrough, Heather. "Why The Coronavirus Pandemic Is Creating A Surge In Renewable Energy". Forbes. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "ECB announces €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP)" (Press release). European Central Bank. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "A Just Recovery from COVID-19". 350.org. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "The ECB will keep on funding polluters". Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "ECB injects over €7 billion into fossil fuels since start of COVID-19 crisis". Greenpeace European Unit. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Elkerbout, M., Egenhofer, C., Núñez Ferrer,, J., Cătuţi, M., Kustova,, I., & Rizos, V. (2020). The European Green Deal after Corona: Implications for EU climate policy. Brussels: CEPS.

- "EU recovery fund's debt-pooling is massive shift for bloc". euronews. 28 May 2020.

- "EU's financial 'firepower' is 1.85 trillion with 750bn for COVID fund". euronews. 27 May 2020.

- Simon, Frédéric. "'Do no harm': EU recovery fund has green strings attached". Euroactive. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus disrupts global fight to save endangered species". AP NEWS. 6 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Text-Only NPR.org : Climate Change Push Fuels Split On Coronavirus Stimulus". NPR. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Put clean energy at the heart of stimulus plans to counter the coronavirus crisis—Analysis". IEA. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Earth Overshoot Day June Press Release". overshootday.org. Global Footprint Network. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Braun, Stuart (21 August 2020). "Coronavirus Pandemic Delays 2020 Earth Overshoot Day by Three Weeks, But It's Not Sustainable". Deutsche Welle. Ecowatch. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Meredith, Sam (18 June 2020). "IEA outlines $3 trillion green recovery plan for world leaders to help fix the global economy". CNBC. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Experts issue recommendations for a green COVID-19 economic recovery". phys.org. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- SOKRATOUS, Zinonas (20 May 2020). "European Semester Spring Package: Recommendations for a coordinated response to the coronavirus pandemic". Cyprus - European Commission. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Harvey, Fiona (18 June 2020). "World has six months to avert climate crisis, says energy expert". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "Publikation - Der Doppelte Booster". www.agora-energiewende.de (in German). Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "A Green Stimulus Plan for a Post-Coronavirus Economy". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Priorities for a green recovery following coronavirus". CBI. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Climate Change and COVID-19: UN urges nations to 'recover better'". Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Pfeifer, Hazel. "Ocean investment could aid post-Covid-19 economic recovery". CNN. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- "Put clean energy at the heart of stimulus plans to counter the coronavirus crisis – Analysis". International Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Political decisions, economic realities: The underlying operating cashflows of coal power during COVID-19". Carbon Tracker. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Milman, Oliver; Holden, Emily (27 March 2020). "Trump administration allows companies to break pollution laws during coronavirus pandemic". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "The epidemic provides a chance to do good by the climate". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Environmental health and strengthening resilience to pandemics". OECD. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Huet, Natalie (12 May 2020). "Chain reaction: commuters and cities embrace cycling in COVID-19 era". euronews.

- "'Surprisingly rapid' rebound in carbon emissions post-lockdown". the Guardian. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- "Environmental health and strengthening resilience to pandemics". OECD. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "The Guardian view on Brazil and the Amazon: don't look away | Editorial". The Guardian. 5 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Press release (24 March 2020). "Drop in aircraft observations could have impact on weather forecasts". European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Lecocq, Thomas; Hicks, Stephen P.; Van Noten, Koen; van Wijk, Kasper; Koelemeijer, Paula; De Plaen, Raphael S. M.; Massin, Frédérick; Hillers, Gregor; Anthony, Robert E.; Apoloner, Maria-Theresia; Arroyo-Solórzano, Mario; Assink, Jelle D.; Büyükakpınar, Pinar; Cannata, Andrea; Cannavo, Flavio; Carrasco, Sebastian; Caudron, Corentin; Chaves, Esteban J.; Cornwell, David G.; Craig, David; den Ouden, Olivier F. C.; Diaz, Jordi; Donner, Stefanie; Evangelidis, Christos P.; Evers, Läslo; Fauville, Benoit; Fernandez, Gonzalo A.; Giannopoulos, Dimitrios; Gibbons, Steven J.; Girona, Társilo; Grecu, Bogdan; Grunberg, Marc; Hetényi, György; Horleston, Anna; Inza, Adolfo; Irving, Jessica C. E.; Jamalreyhani, Mohammadreza; Kafka, Alan; Koymans, Mathijs R.; Labedz, Celeste R.; Larose, Eric; Lindsey, Nathaniel J.; McKinnon, Mika; Megies, Tobias; Miller, Meghan S.; Minarik, William; Moresi, Louis; Márquez-Ramírez, Víctor H.; Möllhoff, Martin; Nesbitt, Ian M.; Niyogi, Shankho; Ojeda, Javier; Oth, Adrien; Proud, Simon; Pulli, Jay; Retailleau, Lise; Rintamäki, Annukka E.; Satriano, Claudio; Savage, Martha K.; Shani-Kadmiel, Shahar; Sleeman, Reinoud; Sokos, Efthimios; Stammler, Klaus; Stott, Alexander E.; Subedi, Shiba; Sørensen, Mathilde B.; Taira, Taka'aki; Tapia, Mar; Turhan, Fatih; van der Pluijm, Ben; Vanstone, Mark; Vergne, Jerome; Vuorinen, Tommi A. T.; Warren, Tristram; Wassermann, Joachim; Xiao, Han (23 July 2020). "Global quieting of high-frequency seismic noise due to COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures". Science: eabd2438. doi:10.1126/science.abd2438. PMID 32703907.