Cephaloridine

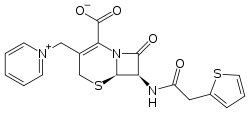

Cephaloridine (or cefaloridine) is a first-generation semisynthetic derivative of antibiotic cephalosporin C. It is a Beta lactam antibiotic, like penicillin. Its chemical structure contains 3 cephems, 4 carboxyl groups and three pyridinium methyl groups.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.048 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H17N3O4S2 |

| Molar mass | 415.48 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cephaloridine is mainly used in veterinary practice. It is unique among cephalosporins in that it exists as a zwitterion.

History

Since the discovery of cephalosporins P, N and C in 1948 there have been many studies describing the antibiotic action of cephalosporins and the possibility to synthesize derivatives. Hydrolysis of cephalosporin C, isolation of 7-aminocephalosporanic acid and the addition of side chains opened the possibility to produce various semi-synthetic cephalosporins. In 1962, cephalothin and cephaloridine were introduced.[1]

Cephaloridine was briefly popular because it tolerated intramuscularly and attained higher and more sustained levels in blood than cephalothin. However, it binds to proteins to a much lesser extent than cephalothin. Because it is also poorly absorbed after oral administration the use of this drug for humans declined rapidly, especially since the second generation of cephalosporins was introduced in the 1970s.[1] Today, it is more commonly used in veterinary practice to treat mild to severe bacterial infections caused by penicillin resistant and penicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella, Clostridium diphtheriae, Salmonella and Shigella.[2] Interest in studying cephalosporins was brought about by some unusual properties of cephaloridine. This antibiotic stands in sharp contrast to various other cephalosporins and to the structurally related penicillins in undergoing little or no net secretion by the mammalian kidney. Cephaloridine is, however, highly cytotoxic to the proximal renal tubule, the segment of the nephron responsible for the secretion of organic anions, including para-am-minohippurate (PAH), as well as the various penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics. The cytotoxicity of cephaloridine is completely prevented by probenecid and several other inhibitors of organic anion transport, including the nearly nontoxic cephalothin.[3]

Structure & reactivity

Cephaloridine is a cephalosporin compound with pyridinium-1-ylmethyl and 2-thienylacetamido side groups. The molecular nucleus, of which all cephalosporins are derivatives, is A3-7-aminocephalosporanic acid. Conformations around the β-lactam rings are quite similar to the molecular nucleus of penicillin, while those at the carboxyl group exocyclic to the dihydrothiazine and thiazolidine rings respectively are different.[4]

Synthesis

Cephaloridine can be synthesised from Cephalotin and pyridine by deacetylation. This can be done by heating an aqueous mixture of cephalotin, thiocyanate, pyridine and phosphoric acid for several hours. After cooling, diluting with water, and adjusting the pH with mineral acid, cephaloridine thiocyanate salt precipitates. This can be purified and converted to cephaloridine by pH adjustment or by interaction with ion-exchange resin.[5]

Clinical use of cephaloridine

Before the 1970s, cephaloridine was used to treat patients with urinary tract infections. Besides the drugs has been used successfully in the treatment of various lower respiratory tract infections. Cephaloridine was very effective to cure pneumococcal pneumonia. It has a high clinical and bacteriological rate of success in staphylococcal and streptococcal infections.[6]

Kinetics

Absorption

Cephaloridine is easily absorbed after intramuscular injection and poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.[7]

Distribution

The minor pathway of elimination is biliary excretion. When the blood serum concentration is 24 µg/ml, the corresponding biliary concentration is 10 µg/ml. In the spinal fluid the concentration of cephaloridine is 6–12% of the concentration in the blood and serum. Cephaloridine is distributed well into the liver, stomach wall, lung and spleen and is also found in fresh wounds one hour after injection. The concentration in the wound will decrease as the wound age increases. However, the drug is poorly penetrated into the cerebrospinal fluid and is found in a much smaller amount in the cerebral cortex.[7]

Pregnancy

When cephaloridine is administered to pregnant women, the drug crosses the placenta. Cephaloridine concentrations can be measured in the serum of the newborn up to 22 hours after labor, and can reach a level of 54% of the concentration in the maternal serum. When given an intramuscular dose of 1 g, a peak occurs in the cord blood after 4 hours. In amniotic fluid, the concentration takes about 3 hours to reach its antibacterial effect.[6]

Metabolism and excretion

Urine specimens showed that no other microbiologically active metabolites were present except cephaloridine and that cephaloridine is excreted unchanged. Renal clearances were reported to be 146–280 ml/min, a plasma clearance of 167 ml/min/1,73m2 and a renal clearance of 125 ml/min/1,73m2. A serum half-life of 1,1-1,5 hour and a volume of distribution of 16 liters were reported.[7]

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic analysis is not possible because appropriate data is not published. The physicochemical properties are almost the same as the other cephalosporins, therefore the pharmacokinetics are comparable.[7]

Adverse effects

Toxicity

Cephaloridine can cause kidney damage in humans, since it is actively taken up from the blood by the proximal tubular cells via an organic anion transporter (OAT) in the basolateral membrane. Organic anions are secreted through the proximal tubular cells via unidirectional transcellular transport. The organic anions are taken up from the blood into the cells across the basolateral membrane and extruded across the brush border membrane into the tubular fluid.[8] Cephaloridine is a substrate for OAT1 and thus can be transported into the proximal tubular cells, which form the renal cortex.[9] The drugs, however, cannot move readily across the luminal membrane since it is a zwitterion. The cationic group (pyridinium ring) of the compound probably inhibits the efflux through the membrane.[9][10] This results in an accumulation of cephaloridine in the renal cortex of the kidney, causing damage and necrosis of the S2 segment of the tubule.[8][9] However, there are no adverse effects on renal function if serum levels of cephaloridine are maintained between 20 and 80 μg/ml.[11]

Metabolism

Cephaloridine is excreted in the urine without undergoing metabolism.[12] It inhibits organic ion transport in the kidney. This process is preceded by the lipid peroxidation. Thereafter, probably a combination of events, such as formation of a reactive intermediate, a free radical and stimulation of lipid peroxidation, lead to peroxidative damage to cell membranes and mitochondria. It is not yet clear whether metabolic activation by cytochromes P-450, chemical rearrangements, reductive activation or all these actions are involved.[9]

The hypotheses made about the mechanism of action causing the toxicity of cephaloridine are:

- Reactive metabolites are formed by cytochromes P-450 or emerge from destabilization of the β-lactam ring. Metabolic activation of the drugs might take place via cytochromes P-450, producing reactive metabolites. This hypothesis is based on the behaviour of some inhibitors of CYP450, which decrease the toxicity, and some inducers of the monooxygenases which increase toxicity. It could also be possible that a reactive intermediate is formed due to the unstable β-lactam ring.[9] The pyridinium side-group of cephaloridine has unstable bonds to the core of the compound (in comparison with other cephalosporins). When this side-group leaves, the β-lactam ring is destabilized by intramolecular electron shifts.[13] Thus, the leaving group creates a reactive product.

- Both lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress can cause membrane damage. Lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress take place as lipid peroxidation products, such as malondialdehyde, have been detected. Reduced glutathione (GSH) and NADPH are both depleted. Consequently, GSSG cannot be reduced to GSH. This leads to an increased toxicity since oxidative stress cannot be reduced. In addition, nephrotoxicity is augmented by deficiency of selenium or tocopherol. The pyridinium side-group interacts with the reduced NADP in a redox cycle. It has been suggested that superoxide anion radicals and hydroxyl radicals may be formed and that lipid peroxidation could be responsible for the toxicity of cephaloridine.[9][13]

- Damage to the mitochondria and intracellular respiratory processes and reduced mitochondrial respiration can cause nephrotoxicity. The previously mentioned damages have been detected after exposure to cephalosporins.[9] β-lactam antibiotics injure mitochondria by an attack on the metabolic substrate carriers of the inner membrane.[13] Respiratory toxicity is caused by inactivation of mitochondrial anion substrate carriers.[8]

Symptoms of kidney damage caused by cephaloridine

Some symptoms caused by cephaloridine are: asymptomatic, enzymuria, proteinuria, tubular necrosis, increased urea level in blood, anemia, increased hydrogen ion level in blood, fatigue, increased blood pressure, increased blood electrolyte level, kidney dysfunction, kidney damage, impaired body water balance and impaired electrolyte balance.[14]

Complications caused by cephaloridine

Complications caused by the use of cephaloridine include seizures, coma, chronic kidney failure, acute kidney failure and death.[14]

Treatment of kidney damage caused by cephaloridine

The damage of the kidneys can be treated by removing the toxin from the body, monitoring and supporting kidney function (dialysis if necessary) and, in severe cases, kidney transplant. Supportive therapy in the acute phase can be done by fluid, electrolyte and hypertension management. Longer term management includes monitoring of renal function, close management of high blood pressure. Furthermore, dietary management may include protein and sodium management, adequate hydration and phosphate and potassium restriction. In case of chronic kidney failure dietary management also includes erythropoietin agonists (since anaemia is associated with chronic kidney failure), phosphate binders (in case of hyperphosphatemia), calcium supplements, Vitamin D supplements and sodium bicarbonate (to correct the acid-base disturbance).[14]

References

- Mason IS, Kietzmann M (1999). "Cephalosporins - pharmacological basis of clinical use in veterinary dermatology". Veterinary Dermatology. 10 (3): 187–92. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3164.1999.00183.x.

- Chaudhary RK, Srivastava AK (1989). "Disposition and dosage regimen of cephaloridine in calves". Veterinary Research Communications. 13 (4): 325–9. doi:10.1007/BF00420839. PMID 2781723. S2CID 11295967.

- Tune BM, Fravert D (November 1980). "Mechanisms of cephalosporin nephrotoxicity: a comparison of cephaloridine and cephaloglycin". Kidney International. 18 (5): 591–600. doi:10.1038/ki.1980.177. PMID 7463955.

- Sweet RM, Dahl LF (January 1969). "The structure of cephaloridine hydrochloride monohydrate". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 34 (1): 14–6. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(69)90520-8. PMID 5762455.

- Osol A, Hoover JE, eds. (1975). Remington's Pharmaceutical Sciences (15th ed.). Easton, Pennsylvania: Mack Publishing Co. p. 1120.

- Owens DR. Advances in Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 13. Academic Press, Inc. pp. 83–170.

- Nightingale CH, Greene DS, Quintiliani R (December 1975). "Pharmacokinetics and clinical use of cephalosporin antibiotics". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 64 (12): 1899–926. doi:10.1002/jps.2600641202. PMID 1107514.

- Takeda M, Tojo A, Sekine T, Hosoyamada M, Kanai Y, Endou H (December 1999). "Role of organic anion transporter 1 (OAT1) in cephaloridine (CER)-induced nephrotoxicity". Kidney International. 56 (6): 2128–36. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00789.x. PMID 10594788.

- Timbrell J (2008). Principles of Biochemical Toxicology (4th ed.). Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC. pp. 332–335. ISBN 978-0-8493-7302-2.

- Schrier, Robert W. (2007). Diseases of the kidney & urinary tract (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1042. ISBN 978-0-7817-9307-0.

- Winchester JF, Kennedy AC (September 1972). "Absence of nephrotoxicity during cephaloridine therapy for urinary-tract infection". Lancet. 2 (7776): 514–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(72)91908-3. PMID 4115572.

- Turck M (1982). "Cephalosporins and related antibiotics: an overview". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 4 Suppl: S281-7. doi:10.1093/clinids/4.Supplement_2.S281. JSTOR 4452882. PMID 7178754.

- Tune BM (December 1997). "Nephrotoxicity of beta-lactam antibiotics: mechanisms and strategies for prevention". Pediatric Nephrology. 11 (6): 768–72. doi:10.1007/s004670050386. PMID 9438663. S2CID 22665680.

- "Kidney damage -- Cephaloridine". RightDiagnosis. Health Grades Inc.