Hypericum perforatum

Hypericum perforatum, known as perforate St John's-wort,[1] common Saint John's wort, or simply St John's wort,[note 1] is a flowering plant in the family Hypericaceae and the type species of the genus Hypericum.

| Hypericum perforatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Hypericaceae |

| Genus: | Hypericum |

| Section: | Hypericum sect. Hypericum |

| Species: | H. perforatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Hypericum perforatum | |

Possibly a hybrid between H. maculatum and H. attenuatum, the species can be found across temperate areas of Eurasia and has been introduced as an invasive weed to much of North and South America, as well as South Africa and Australia. While the species is harmful to livestock and can interfere with prescription drugs, it has been used in folk medicine over centuries, and remains commercially cultivated in the 21st century. Hyperforin, a phytochemical constituent of the species, is under basic research for its possible biological properties.

Description

Perforate St John's wort is a herbaceous perennial plant with extensive, creeping rhizomes. Its reddish stems are erect and branched in the upper section, and can grow up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) high. The stems are woody near their base and may appear jointed from leaf scars.[3] The branches are typically clustered about a depressed base. It has opposite and stalkless leaves that are narrow and oblong in shape and 1–2 cm (0.39–0.79 in) long.[4] Leaves borne on the branches subtend the shortened branchlets. The leaves are yellow-green in color, with scattered translucent dots of glandular tissue.[5] The dots are conspicuous when held up to the light, giving the leaves the "perforated" appearance to which the plant's Latin name refers. The flowers measure up to 2.5 cm (0.98 in) across, have five petals and sepals, and are colored bright yellow with conspicuous black dots.[6] The flowers appear in broad helicoid cymes at the ends of the upper branches, between late spring and early to mid summer. The cymes are leafy and bear many flowers. The pointed sepals have black glandular dots. The many stamens are united at the base into three bundles. The pollen grains are ellipsoidal.[2] The black and lustrous seeds are rough, netted with coarse grooves.[7]

When flower buds (not the flowers themselves) or seed pods are crushed, a reddish/purple liquid is produced.[8]

Taxonomy

Etymology

The specific epithet perforatum is Latin, referring to the perforated appearance of the plant's leaves.[7]

The common name "St John's wort" may refer to any species of the genus Hypericum. Therefore, Hypericum perforatum is sometimes called "common St John's wort" or "perforate St John's wort" to differentiate it.

St John's wort is named as such because it commonly flowers, blossoms and is harvested at the time of the summer solstice in late June, around St John's Feast Day on 24 June. The herb would be hung on house and stall doors on St John's Feast day to ward off evil spirits and to safeguard against harm and sickness to man and live-stock. The genus name Hypericum is possibly derived from the Greek words hyper (above) and eikon (picture), in reference to the tradition of hanging plants over religious icons in the home during St John's Day.

Phylogeny

It is probable that Hypericum perforatum originated as a hybrid between two closely related species with subsequent doubling of chromosomes. One species is certainly a diploid a subspecies of Hypericum maculatum, either subspecies maculatum or immaculatum. Subspecies maculatum is similar in distribution and hybridizes easily with Hypericum perforatum, but subspecies immaculatum is more similar morphologically. The other parent is most likely Hypericum attenuatum as it possesses the features of Hypericum perforatum that Hypericum maculatum lacks. Though Hypericum maculatum is mostly western in its distribution across Eurasia and Hypericum attenuatum is mostly eastern, both species share distribution in Siberia, where hybridization likely took place. However, the subspecies immaculatum now only occurs in south-east Europe.[9]

Ecology

St John's wort reproduces both vegetatively and sexually. Depending on environmental and climatic conditions, and rosette age, St John's wort will alter growth form and habit to promote survival. Summer rains are particularly effective in allowing the plant to grow vegetatively, following defoliation by insects or grazing.[10] The seeds can persist for decades in the soil seed bank, germinating following disturbance.[11]

Distribution

Hypericum perforatum is native to temperate parts of Europe and Asia, but has spread to temperate regions worldwide as a cosmopolitan invasive weed.[12][13] It was introduced to North America from Europe.[14] The species thrives in areas with either a winter- or summer-dominant rainfall pattern; however, distribution is restricted by temperatures too low for seed germination or seedling survival.[12] Altitudes greater than 1500 m, rainfall less than 500 mm, and a daily mean temperature greater than 24 °C are considered limiting thresholds.[10]

Habitat

The flower occurs in prairies, pastures, and disturbed fields. It prefers sandy soils.[3]

Diseases

H. perforatum is affected by phytoplasma diseases, and when infected with Candidatus phytoplasma fraxini in undergoes several phytochemical changes and shows visible symptoms, including yellowing and witches' bloom symptoms. Naphthodianthrone, flavonoid, amentoflavone, and pseudohypericin levels are reduced; chlorogenic acid levels increased. Additionally, phytoplasma diseases greatly reduced the essential oil yield of the plant.[15]

Invasiveness

Although Hypericum perforatum is grown commercially in some regions of southeast Europe, it is listed as a noxious weed in more than twenty countries and has introduced populations in South and North America, India, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa.[12][11] In pastures, St John's wort acts as both a toxic and invasive weed. It replaces native plant communities and forage vegetation to the extent of making productive land nonviable or becoming an invasive species in natural habitats and ecosystems.[16] Ingestion by livestock such as horses, sheep, and cattle can cause photosensitization, central nervous system depression, spontaneous abortion, or death.[16][17] Effective herbicides for control of Hypericum perforatum include 2,4-D, picloram, and glyphosate. In western North America the beetles Chrysolina quadrigemina, C. hyperici, and Agrilus hyperici have been introduced as biocontrol agents.[18]

Full plant

Full plant Seedlings

Seedlings Fruit

Fruit Blossom

Blossom

Traditional medicine

Common St John's wort has long been used in herbalism for centuries.[19][20] It was thought to have medical properties in classical antiquity and was a standard component of theriacs, from the Mithridate of Aulus Cornelius Celsus' De Medicina (ca. 30 CE) to the Venice treacle of d'Amsterdammer Apotheek in 1686. Folk usages included oily extract ("St John's oil") and Hypericum snaps. Hypericum perforatum is a common species and is grown commercially for use in herbalism and traditional medicine.[20]

The red, oily extract of H. perforatum has been used in the treatment of wounds, including by the Knights Hospitaller, the Order of St John, after battles in the Crusades, which is most likely where the name derived.[19][21] Both hypericin and hyperforin are under study for their potential antibiotic properties.[22]

Side effects

St John's wort may cause allergic reactions and can interact in dangerous, sometimes life-threatening ways with a variety of prescribed medicines.[20][19] St John's wort is generally well tolerated, but it may cause gastrointestinal discomfort (such as nausea, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, and diarrhea), dizziness, confusion, fatigue, sedation, dry mouth, restlessness, and headache.[20][23][24][25][26]

The organ systems associated with adverse drug reactions to St John's wort and fluoxetine (an SSRI) have a similar incidence profile;[27] most of these reactions involve the central nervous system.[27] St John's wort also decreases the levels of estrogens, such as estradiol, by accelerating its metabolism, and should not be taken by women on contraceptive pills.[19] St John's wort may cause photosensitivity. This can lead to visual sensitivity to visible and ultraviolet light and to sunburns in situations that would not normally cause them.[23]

Interactions

St John's wort can interfere with the effects of many prescription drugs,[19][20] including the anti-psychotics risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone (i.e. paliperidone, Xeplion or Invega),[28][29] cyclosporine, digoxin, HIV drugs, cancer medications including irinotecan, and warfarin.[19][20] Combining both St John's wort and antidepressants could lead to increased serotonin levels causing serotonin syndrome.[30] It should not be taken with the heart medication ranolazine.[31] Combining estrogen-containing oral contraceptives with St John's wort can lead to decreased efficacy of the contraceptive and, potentially, unplanned pregnancies.[32] Consumption of St John's wort is discouraged for those with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or dementia, and for people using dietary supplements, headache medicine, anticoagulants, and birth control pills.[19][20]

Pharmacokinetics

St John's wort has been shown to cause multiple drug interactions through induction of the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP1A2. This drug-metabolizing enzyme induction results in the increased metabolism of certain drugs, leading to decreased plasma concentration and potential clinical effect.[33] The principal constituents thought to be responsible are hyperforin and amentoflavone. There is strong evidence that the mechanism of action of these interactions is activation of the pregnane X receptor.[34]

St John's wort has also been shown to cause drug interactions through the induction of the P-glycoprotein efflux transporter. Increased P-glycoprotein expression results in decreased absorption and increased clearance of certain drugs, leading to lower plasma concentrations and impaired clinical efficacy.[29]

| Class | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Antiretrovirals | Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors |

| Benzodiazepines | Alprazolam, midazolam |

| Hormonal contraception | Combined oral contraceptives |

| Immunosuppressants | Calcineurin inhibitors, cyclosporine, tacrolimus |

| Antiarrhythmics | Amiodarone, flecainide, mexiletine |

| Beta-blockers | Metoprolol, carvedilol |

| Calcium channel blockers | Verapamil, diltiazem, amlodipine, pregabalin |

| Statins (cholesterol-reducing medications) | Lovastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin |

| Others | Digoxin, methadone, omeprazole, phenobarbital, theophylline, warfarin, levodopa, buprenorphine, irinotecan, risperidone, paliperidone |

| Reference: Rossi, 2005; Micromedex | |

Livestock poisoning

In large doses, St John's wort is poisonous to grazing livestock (cattle, sheep, goats, horses).[16] Behavioural signs of poisoning are general restlessness and skin irritation. Restlessness is often indicated by pawing of the ground, headshaking, head rubbing, and occasional hindlimb weakness with knuckling over, panting, confusion, and depression. Mania and hyperactivity may also result, including running in circles until exhausted. Observations of thick wort infestations by Australian graziers include the appearance of circular patches giving hillsides a 'crop circle' appearance, it is presumed, from this phenomenon. Animals typically seek shade and have reduced appetite. Hypersensitivity to water has been noted, and convulsions may occur following a knock to the head. Although general aversion to water is noted, some may seek water for relief.

Severe skin irritation is physically apparent, with reddening of non-pigmented and unprotected areas. This subsequently leads to itch and rubbing, followed by further inflammation, exudation, and scab formation. Lesions and inflammation that occur are said to resemble the conditions seen in foot and mouth disease. Sheep have been observed to have face swelling, dermatitis, and wool falling off due to rubbing. Lactating animals may cease or have reduced milk production; pregnant animals may abort. Lesions on udders are often apparent. Horses may show signs of anorexia, depression (with a comatose state), dilated pupils, and injected conjunctiva.

Diagnosis

Increased respiration and heart rate is typically observed while one of the early signs of St John's wort poisoning is an abnormal increase in body temperature. Affected animals will lose weight, or fail to gain weight; young animals are more affected than old animals. In severe cases death may occur, as a direct result of starvation, or because of secondary disease or septicaemia of lesions. Some affected animals may accidentally drown. Poor performance of suckling lambs (pigmented and non-pigmented) has been noted, suggesting a reduction in the milk production, or the transmission of a toxin in the milk. It may result in an undesirable flavor.[35]

Photosensitisation

Most clinical signs in animals are caused by photosensitisation.[36] Plants may induce either primary or secondary photosensitisation:

- primary photosensitisation directly from chemicals contained in ingested plants

- secondary photosensitisation from plant-associated damage to the liver.

Araya and Ford (1981) explored changes in liver function and concluded there was no evidence of Hypericum-related effect on the excretory capacity of the liver, or any interference was minimal and temporary. However, evidence of liver damage in blood plasma has been found at high and long rates of dosage.

Photosensitisation causes skin inflammation by a mechanism involving a pigment or photodynamic compound, which when activated by a certain wavelength of light leads to oxidation reactions in vivo. This leads to tissue lesions, particularly noticeable on and around parts of skin exposed to light. Lightly covered or poorly pigmented areas are most conspicuous. Removal of affected animals from sunlight results in reduced symptoms of poisoning.

Chemistry

Detection in body fluids

Hypericin, pseudohypericin, and hyperforin may be quantitated in plasma as confirmation of usage and to estimate the dosage. These three active substituents have plasma elimination half-lives within a range of 15–60 hours in humans. None of the three has been detected in urine specimens.[37]

Chemical constituents

The plant contains the following:[38][39]

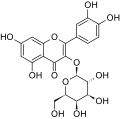

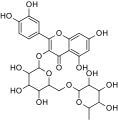

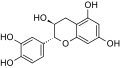

- Flavonoids (e.g. epigallocatechin, rutin, hyperoside, isoquercetin, quercitrin, quercetin, amentoflavone, biapigenin, astilbin, myricetin, miquelianin, kaempferol, luteolin)

- Phenolic acids (e.g. chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid)

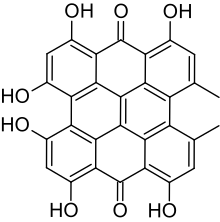

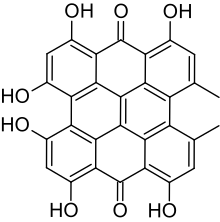

- Naphthodianthrones (e.g. hypericin, pseudohypericin, protohypericin, protopseudohypericin)

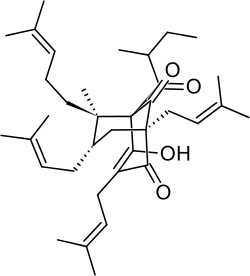

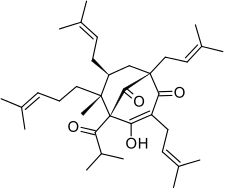

- Phloroglucinols (e.g. hyperforin, adhyperforin)

- Tannins (unspecified, proanthocyanidins reported)

- Volatile oils (e.g. 2-methyloctane, nonane, 2-methyldecane, undecane, α-pinene, β-pinene, α-terpineol, geraniol, myrcene, limonene, caryophyllene, humulene)

- Saturated fatty acids (e.g. isovaleric acid (3-methylbutanoic acid), myristic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid)

- Alkanols (e.g. 1-tetracosanol, 1-hexacosanol)

- Vitamins & their analogues (e.g. carotenoids, choline, nicotinamide, nicotinic acid)

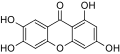

- Miscellaneous others (e.g. pectin, β-sitosterol, hexadecane, triacontane, kielcorin, norathyriol)

The naphthodianthrones hypericin and pseudohypericin along with the phloroglucinol derivative hyperforin are thought to be among the numerous active constituents.[2][40][41][42] It also contains essential oils composed mainly of sesquiterpenes.[2]

Pseudohypericin

Pseudohypericin

Kielcorin

Kielcorin Norathyriol

Norathyriol

Research

Antidepressant

While some studies and research reviews have supported the efficacy of St John's wort as a treatment for depression in humans, in the United States, it is not recommended as a replacement for more studied treatments, and it is advised that symptoms of depression warrant proper medical consultation.[19] A 2015 meta-analysis review concluded that it has superior efficacy to placebo in treating depression, is as effective as standard antidepressant pharmaceuticals for treating depression, and has fewer adverse effects than other antidepressants.[43] The authors concluded that it is difficult to assign a place for St. John's wort in the treatment of depression owing to limitations in the available evidence base, including large variations in efficacy seen in trials performed in German-speaking relative to other countries. In Germany, St. John's wort may be prescribed for mild to moderate depression, especially in children and adolescents.[44] A 2008 Cochrane review of 29 clinical trials concluded that it was superior to placebo in patients with major depression, as effective as standard antidepressants and had fewer side-effects.[45] A 2016 review noted that use of St. John's wort for mild and moderate depression was better than placebo for improving depression symptoms, and comparable to antidepressant medication.[46] A 2017 meta-analysis found that St. John’s wort had comparable efficacy and safety to SSRIs for mild-to-moderate depression and a lower discontinuation rate.[47]

In the United States, St John's wort is considered a dietary supplement by the FDA, and is not regulated by the same standards as a prescription drug.[48][49] According to the United States National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, "St. John’s wort isn’t consistently effective for depression;"[19] Supplement strength varies by manufacturer and possibly by batch.[50] With antidepressants, one "may have to try a few before finding what works best," notes the United States National Library of Medicine[51] On average, lead levels in women taking St. John's wort are elevated about 20%.[52][53]

In vitro research and phytochemicals

St John's wort, similarly to other herbs, contains different chemical constituents.[38][54][55] Although St. John's wort is sold as a dietary supplement, there are no standardized manufacturing procedures, and some marketed products may be contaminated with metals, fillers or other impurities.[20]

| Compound | Conc.[38] [39][57] | log P | PSA | pKa | Formula | MW | CYP1A2 [Note 1] | CYP2C9 [Note 2] | CYP2D6 [Note 3] | CYP3A4 [Note 4] | PGP [Note 5] | t1/2[57] (h) | Tmax[57] (h) | Cmax[57] (mM) | CSS[57] (mM) | Notes/Biological activity[Note 6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phloroglucinols (2–5%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Adhyperforin | 0.2–1.9 | 10–13 | 71.4 | 8.51 | C36H54O4 | 550.81 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Hyperforin | 2–4.5 | 9.7–13 | 71.4 | 8.51 | C35H52O4 | 536.78 | + | +/- | – | + | + | 3.5–16 | 2.5–4.4 | 15-235 | 53.7 | – |

| Naphthodianthrones (0.03-3%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Hypericin | 0.003-3 | 7.5–10 | 156 | 6.9±0.2 | C30H16O8 | 504.44 | 0 | – (3.4 μM) | – (8.5 μM) | – (8.7 μM) | ? | 2.5–6.5 | 6–48 | 0.66-46 | ? | ? |

| Pseudohypericin | 0.2–0.23 | 6.7±1.8 | 176 | 7.16 | C30H16O9 | 520.44 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 24.8–25.4 | 3 | 1.4–16 | 0.6–10.8 | – |

| Flavonoids (2–12%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Amentoflavone | 0.01–0.05 | 3.1–5.1 | 174 | 2.39 | C30H18O10 | 538.46 | ? | – (35 nM) | – (24.3 μM) | – (4.8 μM) | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Apigenin | 0.1–0.5 | 2.1±0.56 | 87 | 6.63 | C15H10O5 | 270.24 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Catechin | 2–4 | 1.8±0.85 | 110 | 8.92 | C15H14O6 | 290.27 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Epigallocatechin | ? | −0.5–1.5 | 131 | 8.67 | C15H14O6 | 290.27 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 1.7±0.4a | 1.3–1.6a | ? | ? | ? |

| Hyperoside | 0.5-2 | 1.5±1.7 | 174 | 6.17 | C21H20O12 | 464.38 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Kaempferol | ? | 2.1±0.6 | 107 | 6.44 | C15H10O6 | 286.24 | ? | ? | ? | +/- | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Luteolin | ? | 2.4±0.65 | 107 | 6.3 | C15H10O6 | 286.24 | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Quercetin | 2–4 | 2.2±1.5 | 127 | 6.44 | C15H10O7 | 302.24 | – (7.5 μM) b | – (47 μM) b | – (24 μM) b | – (22 μM) b | – | 20–72c | 8c | ? | ? | ? |

| Rutin | 0.3–1.6 | 1.2±2.1 | 266 | 6.43 | C27H30O16 | 610.52 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Phenolic acids (~0.1%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Caffeic acid | 0.1 | 1.4±0.4 | 77.8 | 3.64 | C9H8O4 | 180.16 | ? | ? | ? | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Chlorogenic acid | <0.1% | -0.36±0.43 | 165 | 3.33 | C16H18O9 | 354.31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Acronym/Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| MW | Molecular weight in g•mol−1. |

| PGP | P-glycoprotein |

| t1/2 | Elimination half-life in hours |

| Tmax | Time to peak plasma concentration in hours |

| Cmax | Peak plasma concentration in mM |

| CSS | Steady state plasma concentration in mM |

| Partition coefficient. | |

| PSA | Polar surface area of the molecule in question in square angstroms (Å2). Obtained from PubChem (the access date is 13 December 2013). |

| Conc. | These values pertain to the approximation concentration (in %) of the constituents in the fresh plant material |

| – | Indicates inhibition of the enzyme in question. |

| + | Indicates an inductive effect on the enzyme in question. |

| 0 | No effect on the enzyme in question. |

| 5-HT | 5-hydroxytryptamine – synonym for serotonin. |

| DA | Dopamine |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| Glu | Glutamate |

| Gly | Glycine |

| Ch | Choline |

| a | ? |

| b | ? |

| c | ? |

Notes:

- In brackets is the IC50/EC50 value depending on whether it is an inhibitory or inductive action being exhibited, respectively.

- As with last note

- As with last note

- As with last note

- As with last note

- Values given in brackets are IC50/EC50 depending on whether it's an inhibitory or inductive action the compound displays towards the biologic target in question. If it pertains to bacterial growth inhibition the value is MIC50

Other

A major constituent chemical, hyperforin, may be useful for treatment of alcoholism, although dosage, safety and efficacy have not been studied.[58][59] Hyperforin has also displayed antibacterial properties against Gram-positive bacteria, although dosage, safety and efficacy have not been studied.[60] Herbal medicine has also employed lipophilic extracts from St John's wort as a topical remedy for wounds, abrasions, burns, and muscle pain.[59] The positive effects that have been observed are generally attributed to hyperforin due to its possible antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects.[59] For this reason hyperforin may be useful in the treatment of infected wounds and inflammatory skin diseases.[59] In response to hyperforin's incorporation into a new bath oil, a study to assess potential skin irritation was conducted which found good skin tolerance of St John's wort.[59]

See also

Notes

- Less common names and synonyms include Tipton's weed, rosin rose, goatweed, chase-devil, or Klamath weed.[2]

References

- "BSBI List 2007". Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Mehta, Sweety (18 December 2012). "Pharmacognosy of St. John's Wort". Pharmaxchange.info. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- James L. Stubbendieck; Stephan L. Hatch; L. M. Landholt (2003). North American Wildland Plants: A Field Guide (illustrated ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 323. ISBN 9780803293069.

- Rose, F (2006). The wild flower key. Frederick Warne. p. 176. ISBN 9780723251750.

- Zobayed SM, Afreen F, Goto E, Kozai T (2006). "Plant–Environment Interactions: Accumulation of Hypericin in Dark Glands of Hypericum perforatum". Annals of Botany. 98 (4): 793–804. doi:10.1093/aob/mcl169. PMC 2806163. PMID 16891333.

- Stace, C. A. (2010). New Flora of the British Isles (Third ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 339. ISBN 9780521707725.

- Merrit Lyndon Fernald (1970). R. C. Rollins (ed.). Gray's Manual of Botany (Eighth (Centennial) – Illustrated ed.). D. Van Nostrand Company. p. 1010. ISBN 978-0-442-22250-5.

- "St John's wort Hypericum perforatum". Project Noah. 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Edzard Ernst, ed. (2003). Hypericum: The genus Hypericum. CRC Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781420023305.

- Ramawat, Kishan Gopal. Bioactive Molecules and Medicinal Plants. Springer Science & Business Media, 2008. p. 152. ISBN 9783540746034

- "SPECIES: Hypericum perforatum" (PDF). Fire Effects Information System.

- Ian Popay (22 June 2015). "Hypericum perforatum (St John's wort)". CABI. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "Hypericum perforatum L." Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Charles Vancouver Piper; Rolla Kent Beattie (1915). Flora of the Northwest Coast. Press of the New era printing Company. p. 240.

- Marcone, C. (2016). "Phytoplasma Diseases of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants". Journal of Plant Pathology. 98 (3): 379–404. JSTOR 44280481.

- "St John's wort – Hypericum perforatum". North West Weeds. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Watt, John Mitchell; Breyer-Brandwijk, Maria Gerdina: The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa 2nd ed Pub. E & S Livingstone 1962

- John L. Harper (2010). Population Biology of Plants. Blackburn Press. ISBN 978-1-932846-24-9.

- "St. John's Wort". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health. September 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "St. John's wort". Drugs.com. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Süntar, Ipek Peşin; Akkol, Esra Küpeli; Yılmazer, Demet; Baykal, Turhan; Kırmızıbekmez, Hasan; Alper, Murat; Yeşilada, Erdem (2010). "Investigations on the in vivo wound healing potential of Hypericum perforatum L.". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 127 (2): 468–77. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.10.011. PMID 19833187.

- Schempp, Christoph M; Pelz, Klaus; Wittmer, Annette; Schöpf, Erwin; Simon, Jan C (1999). "Antibacterial activity of hyperforin from St John's wort, against multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus and gram-positive bacteria". The Lancet. 353 (9170): 2129. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00214-7. PMID 10382704. S2CID 26975932.

- Ernst E, Rand JI, Barnes J, Stevinson C (1998). "Adverse effects profile of the herbal antidepressant St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.)". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 54 (8): 589–94. doi:10.1007/s002280050519. PMID 9860144. S2CID 25726974.

- Barnes, J.; Anderson, L.A.; Phillipson, J.D. (2002). Herbal Medicines: A guide for healthcare professionals (2nd ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 9780853692898.

- Parker V, Wong AH, Boon HS, Seeman MV (2001). "Adverse reactions to St John's Wort". Can J Psychiatry. 46 (1): 77–9. doi:10.1177/070674370104600112. PMID 11221494.

- Greeson JM, Sanford B, Monti DA (February 2001). "St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum): a review of the current pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical literature". Psychopharmacology. 153 (4): 402–14. doi:10.1007/s002130000625. PMID 11243487. S2CID 22986104.

- Hoban, Claire L.; Byard, Roger W.; Musgrave, Ian F. (July 2015). "A comparison of patterns of spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting with St. John's Wort and fluoxetine during the period 2000–2013". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 42 (7): 747–51. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12424. PMID 25988866. S2CID 22189214.

The organ systems affected by ADRs to St John's Wort and fluoxetine have a similar profile, with the majority of cases affecting the central nervous system (45.2%, 61.7%).

- Wang, J. S.; Ruan, Y.; Taylor, R. M.; Donovan, J. L.; Markowitz, J. S.; Devane, C. L. (2004). "The Brain Entry of Risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone Is Greatly Limited by P-glycoprotein". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 7 (4): 415–9. doi:10.1017/S1461145704004390. PMID 15683552.

- Gurley BJ, Swain A, Williams DK, Barone G, Battu SK (2008). "Gauging the clinical significance of P-glycoprotein-mediated herb-drug interactions: comparative effects of St. John's wort, Echinacea, clarithromycin, and rifampin on digoxin pharmacokinetics". Mol Nutr Food Res. 52 (7): 772–9. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700081. PMC 2562898. PMID 18214850.

- Borrelli, F; Izzo, AA (December 2009). "Herb-drug interactions with St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum): an update on clinical observations". The AAPS Journal. 11 (4): 710–27. doi:10.1208/s12248-009-9146-8. PMC 2782080. PMID 19859815.

- "Renolazine". MedlinePlus, US National Library of Medicine. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- Russo, Emilio; Scicchitano, Francesca; Whalley, Benjamin J.; Mazzitello, Carmela; Ciriaco, Miriam; Esposito, Stefania; Patanè, Marinella; Upton, Roy; Pugliese, Michela; Chimirri, Serafina; Mammì, Maria; Palleria, Caterina; De Sarro, Giovambattista (May 2014). "Hypericum perforatum: pharmacokinetic, mechanism of action, tolerability, and clinical drug-drug interactions". Phytotherapy Research. 28 (5): 643–655. doi:10.1002/ptr.5050. PMID 23897801. S2CID 5252667.

- Wenk M, Todesco L, Krähenbühl S (2004). "Effect of St John's wort on the activities of CYP1A2, CYP3A4, CYP2D6, N-acetyltransferase 2, and xanthine oxidase in healthy males and females". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 57 (4): 495–499. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02049.x. PMC 1884478. PMID 15025748.

- Kober M, Pohl K, Efferth T (2008). "Molecular mechanisms underlying St. John's wort drug interactions". Curr. Drug Metab. 9 (10): 1027–37. doi:10.2174/138920008786927767. PMID 19075619.

- Reiner, Ralph E. (1969). Introducing the Flowering Beauty of Glacier National Park and the Majestic High Rockies. Glacier Park, Inc. p. 64.

- "St John's wort". North West Weeds. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1445–1446.

- Barnes, J.; Anderson, L.A.; Phillipson, J.D. (2007) [1996]. Herbal Medicines (PDF) (3rd ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-623-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Greeson JM, Sanford B, Monti DA (February 2001). "St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum): a review of the current pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical literature" (PDF). Psychopharmacology. 153 (4): 402–414. doi:10.1007/s002130000625. PMID 11243487. S2CID 22986104. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014.

- Umek A, Kreft S, Kartnig T, Heydel B (1999). "Quantitative phytochemical analyses of six hypericum species growing in slovenia". Planta Med. 65 (4): 388–90. doi:10.1055/s-2006-960798. PMID 17260265.

- Tatsis EC, Boeren S, Exarchou V, Troganis AN, Vervoort J, Gerothanassis IP (2007). "Identification of the major constituents of Hypericum perforatum by LC/SPE/NMR and/or LC/MS". Phytochemistry. 68 (3): 383–93. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.11.026. PMID 17196625.

- Schwob I, Bessière JM, Viano J.Composition of the essential oils of Hypericum perforatum L. from southeastern France.C R Biol. 2002;325:781-5.

- Linde K, Kriston L, Rücker G, Jamila S, Schumann I, Meissner K, Sigterman K, Schneider A (February 2015). "Efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: systematic review and network meta-analysis". Annals of Family Medicine. 13 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1370/afm.1687. PMC 4291268. PMID 25583895.

- Dörks, M.; Langner, I.; Dittmann, U.; Timmer, A.; Garbe, E. (August 2013). "Antidepressant drug use and off-label prescribing in children and adolescents in Germany: results from a large population-based cohort study". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 22 (8): 511–8. doi:10.1007/s00787-013-0395-9. PMID 23455627. S2CID 6692193.

- Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L (2008). Linde K (ed.). "St John's wort for major depression". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD000448. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000448.pub3. PMC 7032678. PMID 18843608.

- Apaydin EA, Maher AR, Shanman R, Booth MS, Miles JN, Sorbero ME, Hempel S (2016). "A systematic review of St. John's wort for major depressive disorder". Syst Rev. 5 (1): 148. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0325-2. PMC 5010734. PMID 27589952.

- Ng, Qin; Venkatanarayanan, Nandini; Hoc, Collin (2017). "Clinical use of Hypericum perforatum (St John's wort) in depression: A meta-analysis". Journal of Affective Disorders. 210: 211–221. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.048. PMID 28064110.

- "Information for Consumers – Dietary Supplements: What You Need to Know". FDA.gov. May 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- O'Connor, Anahad (19 January 2016). "'Supplements and Safety' Explores What's in Your Supplements". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Questions and Answers on Current Good Manufacturing Practices—Production and Process Controls". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

Do CGMPs require [...] successful process validation batches [...]? No. Neither the CGMP regulations nor FDA policy specifies a minimum number of batches to validate a manufacturing process.

- "Antidepressants". Medline Plus.

- Buettner, C; Mukamal, KJ; Gardiner, P; Davis, RB; Phillips, RS; Mittleman, MA (November 2009). "Herbal supplement use and blood lead levels of United States adults". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 24 (11): 1175–82. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1050-5. PMC 2771230. PMID 19575271.

- Bouchard, Maryse; et al. (December 2009). "Blood lead levels and major depressive disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder in U.S. young adults". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 66 (12): 1313–1319. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.164. PMC 2917196. PMID 19996036.

- "Pharmacology". Hyperforin. Drugbank. University of Alberta. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- "Targets". Hyperforin. DrugBank. University of Alberta. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- "St. John's wort". Natural Standard. Cambridge, MA. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- Anzenbacher, Pavel; Zanger, Ulrich M., eds. (2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527630905. ISBN 978-3-527-63090-5.

- Kumar V, Mdzinarishvili A, Kiewert C, Abbruscato T, Bickel U, van der Schyf CJ, Klein J (2006). "NMDA receptor-antagonistic properties of hyperforin, a constituent of St. John's Wort" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Sci. 102 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0060378. PMID 16936454.

- Reuter J, Huyke C, Scheuvens H, Ploch M, Neumann K, Jakob T, Schempp CM (2008). "Skin tolerance of a new bath oil containing St. John's wort extract". Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 21 (6): 306–311. doi:10.1159/000148223. PMID 18667843. S2CID 5167159.

- Cecchini C, Cresci A, Coman MM, Ricciutelli M, Sagratini G, Vittori S, Lucarini D, Maggi F (2007). "Antimicrobial activity of seven hypericum entities from central Italy". Planta Med. 73 (6): 564–6. doi:10.1055/s-2007-967198. PMID 17516331.