History of Thrissur

Thrissur (Malayalam: തൃശൂർ) is the administrative capital of Thrissur District situated in the central part of Kerala state, India. Thrissur district was formed on 1 July 1949. It is an important cultural centre, and is known as the Cultural Capital of Kerala. It is famous for the Thrissur Pooram festival, one of the most colourful and spectacular temple festival of Kerala. From ancient times, Thrissur has played a significant part in the political, economical and cultural history of Indian sub continent and South East Asia. It has opened the gates for Arabs, Romans, Portuguese, Dutch and English. Thrissur is where Christianity, Islam and Judaism entered the Indian sub continent, when Thomas the Apostle arrived in 52 CE and the location of country's first Mosque in the 7th century.[1]

| Timeline of Thrissur | |

| |

| Year | Event |

| 1200 BCE – 200 CE | Iron Age Megalithic Culture |

| 2nd–1st century BCE | Rise of Muziris as a port |

| 1st–3rd centuries CE | Roman coins of the period found |

| 800–1124 | Rule of Perumals of Mahodayapuram |

| 855 | Sthanu Ravi inscription at Koodalmanikyam Temple at Irinjalakuda |

| 930 | Kota Ravi inscriptions at Avittathur |

| 1000 | Jewish Copper plate issued at Mahodayapuram |

| 1024 | Rajasimha inscription at Thazhekad |

| 1036 | Rajasimha inscription at Thiruvanchikulam Temple |

| 11th century | Inscription at Vadakkumnathan Temple, Thrissur |

| 1225 | Syrian Christian copper plate issued by Vira Raghava of Perumpadapu Swaroopam |

| 1523 | Portuguese Fort at Cranganore |

| 1599 | Syrian Christian priests from Palayoor and Mattom take part in the Synod of Diamper |

| 1606, 1677, 1681 | Inscriptions at Palayoor |

| 1710 | Dutch control over Chettuva |

| 1750–1762 | Zamorin's occupation of Thrissur |

| 1789 | Tipu Sultan's occupation of Thrissur |

| 1790–1805 | Rule of Rama Varma, Sakthan Thampuran |

| 1791 | Treaty between Cochin and the East India Company by which Kingdom of Cochin became a vassal of the company |

| 1794 | Fortifications around the Thrissur town by Sakthan Thampuran |

| 1800 | Cochin State placed under the Madras Government |

| 1814 | Construction of the Mart Mariam Big Church at Thrissur |

| 1816 | The first known map of Thrissur prepared by John Gould |

| 1889 | St. Thomas College, Thrissur founded |

| 1921 | Thrissur made a municipality |

| 1925 | Cochin Legislative Council with elected members from Thrissur |

| 1925, 1927 | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi visits Thrissur |

| 1932 | E.M.S. Namboodiripad left St. Thomas College, Thrissur to enlist himself a volunteer of the Indian National Congress at Kozhikode |

| 1935 | Labour Brotherhood in Thrissur |

| 1936 | Cochin State Congress founded |

| 1936 | Electricity agitation |

| 1940 | Cochin Karshakasabha founded |

| 1941 | Cochin State Prajamandal |

| 1947 | Temple entry allowed in Cochin |

| 1949 | Travancore-Cochin State comes into existence |

| 1 July 1949 | Thrissur district was formed |

| 1956 | Formation of Kerala State |

Etymology

The name Thrissur is derived from 'Thiru-Shiva-Perur', which literally translates to "The City with the name of the Lord Siva". Thrissur was also known as "Vrishabhadripuram" and "Thenkailasam" (Kailasam of the South) in ancient days. Another interpretation is 'Tri-shiva-peroor' or the big land with 3 Shiva temples, which refers to the three places where Lord Shiva resides – namely Vadakkumnathan Temple, Asokeswaram Siva Temple near Vadakkechira, North Bus stand, Irattachira Siva Temple, Near Sakthan Bus stand

Pre-history

.JPG.webp)

Starting from the Stone Age, Thrissur must have been the site of human settlement. This is evidenced by the presence of a megalithic monuments at Ramavarmapuram, Kuttoor, Cherur and Villadam.[2] The Ramavarmapuram monument is in granite and is of Menhir type. The monument in Ramavarmapuram is 15 feet height and 12 feet 4 inches broad. From 1944, it is under the protection of Department of Archaeology. The monument is locally known as 'Padakkallu' or 'Pulachikkallu'. These menhirs are memorials for the departed souls put up at burial sites. They belong to the Megalithic Age of Kerala, which is roughly estimated between 1000 BCE and 500 CE.[3] All such monuments have not been dated exactly. Some experts are of the view that these are the remnants of the Neolithic Age in the development of human technology. The Ramavarmapuram Menhir is also believed to be a monument belonging to the Sangam period in the South Indian history.[4]

Another monolithic monuments like Dolmens and rock-cut caves are at Porkulam, Chiramanengad, Eyyal, Kattakambal and Kakkad. The monument excavated under Archaeologist BK Thapar, between 1949–50, was under the Department of Archaeology.[2] Another megalithic monument is situated at Ariyannur in Thrissur. This place has unravelled monuments such as the 'Kudakkallu' or 'Thoppikkallu' (Mushroom stones or Umbrella stones) and 'Munimada' (Saint's abode).[5] The laterite hillocks of Ariyannur rise to about 50 metres. Another reference in Ariyannur dates back to the early 15th century in the poem 'Chandrotsavam'.[5]

Chera Dynasty

The early political history of the Thrissur and Thrissur district is interlinked with that of the Chera Dynasty of the Sangam age, who ruled over vast portions of Kerala with their capital at Vanchi. Kodungallur was also the capital of Cheraman Perumal, the last Chera ruler in the 7th century. The legend is that he abdicated his throne and divided his kingdom among the local chieftains and left for Mecca to embrace Islam. This place was later ruled by the Kingdom of Cochin (Perumpadapu Swaroopam). During the time of the Chera ruler, Kodungallur was an important trade link in Indian Ancient Maritime History.

The whole of the present Thrissur district was included in the early Chera empire. The district can claim to have played a significant part in fostering the trade relations between Kerala and the outside world in the ancient and medieval period. It can also claim to have played an important part in fostering cultural relations and in laying the foundation of a cosmopolitan and composite culture in this part of the country. Muziris (Muchiri) was an important port city in the pre-historic era, was a part of it.

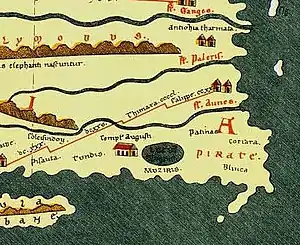

Muziris

Muziris (1st century BCE), is a lost port city in Kodungallur and was a major center of trade in kerala between the Chera Empire and the Roman Empire.[6]Muziris (Cranganore) was destroyed by massive flooding of the river Periyar in 1341, opening a new port called Kochi.[7]Muziris was also known as Mahodayapuram, Shinkli, Muchiri (anglicised to Muziris) and Muyirikkodu. It is known as 'Vanchi' to locals.[6]Muziris opened the gates for Arabs, Romans, Portuguese, Dutch and English to Indian sub continent and South East Asia. Muziris dealers had set Indo-Greek and Indo-Roman trade with Egypt, which comes in gold and other metals, pepper and spices, precious stones and textiles.[8] It was famous as a major port for trade and commerce for more than 2,500 years.

There has always been a lot of confusion about the exact location of the port, as also about other aspects of it. For long it was considered to be Kodungalloor. However, in 1983, a large hoard of Roman coins was found at a site around 10 km from a place called Pattanam, some distance away from Kodungalloor. Excavations carried out from 2004 to 2009 at Pattanam has revealed evidence that may point out the exact position of Muziris.[6][9][10][11]

The recent archaeological work done in the area has revealed fragments of imported Roman amphora, mainly used for transporting wine and olive oil, Yemeni and West Asian pottery, besides Indian roulette ware (which is also common on the East Coast of India, and also found in Berenice in Egypt).[6][9][10][11] This suggests that Muziris was a port of great international fame and that South India was involved in active trade with several civilizations of West Asia, the Near East and Europe with the port as a means to do so.

While there is a consensus on that both the port and the city ceased to exist around the middle of the 13th century, possibly following an earthquake (or the great flood of 1341 recorded in history, which caused the change of course of Periyar river), there does not seem to be clear evidence as to when the port might have first come into being. Presently, researchers seem to be agreed on that the port was already a bustling center of trade by 500 BCE, and there is some evidence that suggests that Muziris was a city, even if not certainly a port as well, from before 1500 BCE.[12][13][14][15]

It is called as 'Murachipatanam' in Sanskrit and Muchiri in Tamil. Later it was also called as Makothai, Mahodayapuram, Mahodayapattanam. The port was familiar to the author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea who described it as being situated on Pseudostomos river (Ψευδόστομος: Greek for "false mouth" – a precise translation of the Malayalam description of the mouth of the Periyar, Alimukam) 3 km from its mouth. According to the Periplus, numerous Greek seamen managed an intense trade with Muziris:[16]

"Then come Naura and Tyndis, the first markets of Damirica (Limyrike), and then Muziris and Nelcynda, which are now of leading importance. Tyndis is of the Kingdom of Cerobothra; it is a village in plain sight by the sea. Muziris, of the same Kingdom, abounds in ships sent there with cargoes from Arabia, and by the Greeks; it is located on a river, distant from Tyndis by river and sea five hundred stadia, and up the river from the shore twenty stadia" – The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, 53–54

Muziris is also mentioned in the epics Ramayana, Mahabharatha, Akananuru, and Chilappathikaram. The poets Pathanjali and Karthiyayan have referred to it, as well as the travelogues of both Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy under different names. Moreover, Kodungallur (Muziris) is mentioned in the stone writings of Ashoka. It was known as Muziris to Pliny the Elder (N.H. 6.26), who describes it as primum emorium Indiae. The ancient Greek explorer Hippalus landed at this port after discovering the patterns of the Indian monsoon trade winds on his way from the aast African coast. Evidence of the Peutinger Table suggests that there was a temple dedicated to the Roman emperor Augustus. The Greeks, the Romans (known locally as the Yavanas) and the Jews, Arabs etc. all have come to this place at different times in its history.

Roman gold and silver coins bearing impressions of Roman Emperors Tiberius and Nero were discovered in the village Kochal in Valluvally-Koonammavu near Paravur near the town in 1983. A 2nd-century papyrus from Egypt concerning the transshipment of goods originating in Muziris from the Red Sea to Alexandria attests to the continued importance of the port in the Indian Ocean commerce trade a century after Pliny and the Periplus.[17]

Thomas the Apostle (51–52)

The indigenous church of Kerala has a tradition that St. Thomas sailed there to spread the Christian faith. He landed at the ancient port of Muziris. He then went to Palayoor (near present-day Guruvayoor), which was a Hindu priestly community at that time. He left Palayoor in 52 for the southern part of what is now Kerala State, where he established the Ezharappallikal, or "Seven and Half Churches". These churches are at Kodungallur, Kollam, Niranam, Nilackal (Chayal), Kokkamangalam, Kottakkavu, Palayoor (Chattukulangara) and Thiruvithancode Arappally – the half church.[18][19]

"It was to a land of dark people he was sent, to clothe them by Baptism in white robes. His grateful dawn dispelled India's painful darkness. It was his mission to espouse India to the One-Begotten. The merchant is blessed for having so great a treasure. Edessa thus became the blessed city by possessing the greatest pearl India could yield. Thomas works miracles in India, and at Edessa Thomas is destined to baptize peoples perverse and steeped in darkness, and that in the land of India." – Hymns of St. Ephraem, edited by Lamy (Ephr. Hymni et Sermones, IV).

Cheraman Juma Masjid (629)

built in 629 by Malik Bin Deenar, Cheraman Juma Masjid is considered as the oldest mosque in India, and the second oldest mosque in the world to offer Jumu'ah prayers.[20][21] Constructed during the lifetime of Muhammad, the bodies of some of his original followers are said to be buried here.[22] Unlike other mosques in Kerala that face westwards this mosque faces eastwards. Though, generally it is considered to be the second mosque of the world after the mosque in Medina, Saudi Arabia.

The legend has it that a group of Muhammad's Sahaba (companions) visited Kodungallur. Cheraman Perumal (Rama Varma Kulashekhara), then the Chera ruler, had witnessed a miraculous happening – the sudden splitting of the moon, the celebrated miracle of Muhammad – and learned on inquiry that this was a symbol of the coming of a Messenger of God from Arabia. Soon after, Perumal travelled to Makkah, where he embraced Islam, and accepted the name Thajudeen. On his way back to India he died at Salalah in the Sultanate of Oman. On his deathbed he is said to have authorised some of his Arab companions to go back to his kingdom to spread Islam. Accordingly, a group of Arabs led by Malik Bin Deenar and Malik bin Habib arrived in north Kerala, and constructed the Cheraman Juma Masjid at Kodungalloor.[20][23][24]

Cochin Royal Family

There is no extant written evidence about the emergence of Kingdom of Cochin or of the Cochin Royal Family, also known as Perumpadapu Swaroopam.[25] All that is recorded are folk tales and stories, and there is a somewhat blurred historical picture about the origins of the ruling dynasty. The surviving manuscripts, such as Keralolpathi, Keralamahatmyam, and Perumpadapu Grandavari, are collections of myths and legends that are less than reliable as conventional historical sources.

There is an oft-recited legend that the last Perumal who ruled Kerala divided his kingdom between his nephews and his sons, converting to Islam and traveling to Mecca on a hajj. The Keralolpathi recounts the above narrative in the following fashion:

The last and the famous Perumal king Cheraman Perumal ruled Kerala for 36 years. He left for Mecca by ship with some Muslims who arrived at Kodungallur (Cranganore) port and converted to Islam. Before leaving for Mecca, he divided his kingdom between his nephews and sons.

The Perumpadapu Grandavari contains an additional account of the dynastic origins:

The last Thavazhi of Perumpadapu Swaroopam came into existence on the Kaliyuga day shodashangamsurajyam. Cheraman Perumal divided the land in half, 17 amsha north of Neelaeswaram and 17 amsha south, totaling 34 amsha, and gave his powers to nephews and sons. Thirty-four rajyas between Kanyakumari and Gokarna, now in Karnataka were given to the Thampuran who was the daughter of the last niece of Cheraman Perumal.

Keralolpathi recorded the division of his kingdom in 345, Perumpadapu Grandavari in 385, Loghan (a historian) in 825. There are no written records on these earlier divisions of Kerala, but according to writer Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai, a division might have occurred during the Second Chera Kingdom, at the beginning of the 12th century.[26]

The history of Thrissur from the 9th to the 12th centuries is the history of Kulasekharas of Mahodayapuram and the history since the 12th century is the history of the rise and growth of Perumpadapu Swaroopam. In the course of its long and chequered history, the Perumpadappu Swarupam had its capital at different places. According to the literary works of the period, the Perumpadapu Swaroopam had its headquarters at Mahodayapuyram and had a number of Naduvazhies in southern Kerala. Central Kerala recognised the supremacy of the Perumpadappu Moopil and he is even referred to as the 'Kerala Chakravarthi' in the 'Sivavilasam' and some other works.[27]

One of the landmarks in the history of the Perumpadapu Swaroopam is the foundation of a new era called Pudu Vaipu era. The Pudu Vaipu era is traditionally believed to have commenced from the date on which the island of Vypeen was thrown from the sea. The 14th and 15th centuries constituted a period of aggressive wars in the course of which the Zamorins of Calicut acquired a large part of the present Thrissur district. In the subsequent centuries the Portuguese dominated the scene. By the beginning of the 17th century the Portuguese power in Kerala was on the verge of collapse. About this time other European powers like the Dutch and the English appeared on the scene and challenged the Portuguese. Internal dissension in the Perumpadappu Swarupam helped the Dutch in getting a footing on the Kerala coast. As the Kerala chiefs were conscious of the impending doom of the Portuguese, they looked upon the Dutch as the rising power and extended a hearty welcome to them.[27]

Flood of 1341

The flood of the river Periyar in 1341 resulted in the splitting of the left branch of the river into two just before Aluva. The flood silted the right branch (known as River Changala) and the natural harbour at the mouth of the river, and resulted in the creation of a new harbour at Kochi. An island was formed with the name Vypinkara between Vypin to Munambam during the flood. During this time there was the rise of the Samoothiri Rajas of Kozhikode. The town was nearly completely destroyed by the Portuguese (Suarez de Menezes) on 1 September 1504 in retaliation for the Samoothiri Raja's actions against them.

Portuguese

Raid on Cranganore

.gif)

October 1504 While in Cochin, Lopo Soares receives reports that the Zamorin of Calicut has dispatched a force to fortify Cranganore, the port city at the northern end of the Vembanad lagoon, and the usual entry point for the Zamorin's army and fleet into the Kerala backwaters. Reading this as a preparation for a renewed attack on Cochin after the 6th Armada leaves, Lopo Soares decides on a preemptive strike. He orders a squadron of around ten fighting ships and numerous Cochinese bateis and paraus, to head up there. The heavier ships, unable to make their way into the shallow channels, anchor at Palliport (Pallipuram, on the outer edge of Vypin island), while those ships, bateis and paraus that can continue on.

Converging on Cranganore, the Portuguese-Cochinese fleet quickly disperses the Zamorin's forces on the beach with cannon fire, and then lands an amphibian assault force – some 1,000 Portuguese and 1,000 Cochinese Nairs, who take on the rest of the Zamorin's forces in close combat. The Zamorin's forces are defeated and driven away from the city.[28] The assault troops capture Cranganore, and subject the ancient city, the once-great Chera capital of Kerala, to a thorough and violent sacking and razing. Deliberate fires were already started by squads led by Duarte Pacheco Pereira and factor Diogo Fernandes Correa, while the main fighting was still going on. They quickly consume most of the city, save for the Syrian Christian quarters, which are carefully spared (Jewish and Muslim homes are not given the same consideration).

In the meantime, the Calicut fleet of some five ships and 80 paraus that had been dispatched to save the city are intercepted by the idling Portuguese ships near Palliport and defeated in a naval encounter.[29] Two days later, the Portuguese receive an urgent message from the ruler of the Kingdom of Tanur (also known as Tanore or Vettattnad), whose kingdom lay to the north, on the road between Calicut and Cranganore. The raja of Tanur had come to loggerheads with his overlord, the Zamorin, and offered to place himself under Portuguese suzerainty instead, in return for military assistance. He reports that a Calicut column, led by the Zamorin himself, had been assembled in a hurry to try to save Cranganore, but that he managed to block its passage at Tanur. Lopo Soares immediately dispatches Pêro Rafael with a caravel and a sizeable Portuguese armed force to assist the Tanurese. The Zamorin's column is defeated and dispersed soon after its arrival.

The raid on Cranganore and the defection of the raja of Tanur were serious setbacks to the zamorin, pushing the frontline north and effectively placing the Vembanad lagoon out of the Zamorin's reach. Any hopes the Zamorin had of quickly resuming his attempts to capture Cochin via the backwaters are effectively dashed. No less importantly, the battles at Cranganore and Tanur, which involved significant numbers of Malabari captains and troops, clearly demonstrated that the Zamorin was no longer feared in the region. The Battle of Cochin had broken his authority. Cranganore and Tanur showed that Malabaris were no longer afraid of defying his authority and taking up arms against him. The Portuguese were no longer just a passing nuisance, a handful of terrifying pirates who came and went once a year. They were a permanent disturbance, turning the old order upside down. A new chapter was being opened on the Malabar coast.

Cranganore Fort (1523)

Cranganore Fort was built by Portuguese in 1523 and later it in 1565 it was enlarged. It is also known as Kottappuram Fort. The Dutch took possession of the fort in 1661. In 1776, Tipu Sultan seized the control of fort. The Dutch wrested it back from Tipu Sultan, but the fort eventually came under the control of Tipu, who destroyed it in the following year. The remains of the fort show that the original fort wall was 18 feet in thickness. The ruin is also known as Tipu's fort.

Mysorean invasion (1773–1790)

The 1773 conquest of the Mysore King Hyder Ali in the Malabar region descended to Kochi. The Kochi Raja had to pay a subsidy of one hundred thousand of Ikkeri Pagodas (equalling 400,000 modern rupees). Later on, in 1776, Hyder Ali capture Thrissur, which was under the Kingdom of Kochi. Thus, the Raja was forced to become a tributary of Mysore and to pay a nuzzar of 100,000 of Pagodas and 4 elephants and annual tribute of 30,000 Pagodas. The hereditary Prime Ministership of Cochin came to an end during this period.

His son Tipu Sultan's invasion had an adverse impact on the Syrian Malabar Nasrani community of the Malabar coast. Many churches in Malabar and Cochin were damaged. Tipu's army set fire to the church at Palayoor and attacked the Ollur Church in 1790. Furthernmore, the Arthat church and the Ambazhakkad seminary was also destroyed. Over the course of this invasion, many Syrian Malabar Nasrani were killed or forcibly converted to Islam. Most of the coconut, arecanut, pepper and cashew plantations held by the Syrian Malabar farmers were also indiscriminately destroyed by the invading army. As a result, when Tipu's army invaded Guruvayur and adjacent areas, the Syrian Christian community fled Calicut and small towns like Arthat to new centres like Kunnamkulam, Chalakudi, Ennakadu, Cheppadu, Kannankode, Mavelikkara, etc. where there were already Christians. They were given refuge by Sakthan Tamburan, the ruler of Cochin and Karthika Thirunal, the ruler of Travancore, who gave them lands, plantations and encouraged their businesses. Colonel Macqulay, the British resident of Travancore also helped them.[30]

Sakthan Thampuran (1790–1805)

In 1790, Raja Rama Varma popularly known as Sakthan Thampuran ascended the throne of Kingdom of Cochin. With the accession of this ruler, the modern period in the history of Kochi and the Thrissur District and the city begin. Sakthan Thampuran was the most powerful maharaja as the very name indicated. His punishment of criminals and wrongdoers was considered harsh but helped restore peace to the country. Sakthan Thampuran had been at the helm of affairs since 1769 when all administrative authority in the Cochin State was delegated to him by the then reigning sovereign on the initiative of the Travancore Raja and the Dutch Governor. As his very name suggests, this Raja was a strong ruler and his reign was characterised by firm and vigorous administration. By the end of the 18th century, the power of the feudal chieftains had been crushed and royal authority had become supreme. Sakthan Thampuran was mainly responsible for the destruction of the power of the feudal chieftains and increase of royal power.

Another potent force in the public life of Thrissur and its suburbs was the Namboothiri community and the Syrian Christian community. A large part of the Thrissur taluk was for long under the domination of the Yogiatiripppads, the ecclesiastical heads of the Vadakkunnathan and Perumanam Devaswoms. The Yogiatirippads were elected and consecrated by the Namboothiri Yogams of the respective places. Under their leadership the Namboothiri families of Thrissur and Perumanam were playing in active part against the ruler of Cochin in his wars against the Zamorin of Calicut. Hence after the expulsion of the Zamorin from Thrissur in 1761, drastic action was taken against these families by the Raja of Cochin. The institution of Yogiatirippads was discontinued and the management of Thrissur and Perumanam Devaswoms were taken over by the Government. The Namboothiri Yogams were reduced to impotence. Thus the anti-feudal measures of Sakthan Thampuran coupled with the several administrative reforms introduced by him marked the end of the medieval period in the history of Cochin and ushered in the modern epoch of progress.

It may be interesting in this connection to know something about the institution of the Yogatirippad. The Yogatirippad of the Vadakkunnathan Devaswom was elected by the Namboothiri illams of Thrissur and its suburbs. The Yogatirippad was elected for life in the presence of the ruler of Cochin, local chieftains and prominent Namboothiri from places outside Thrissur. The Yogatirippad was a very powerful and influential dignitary. The last Yogatirippad was banished from Thrissur in 1763 for having joined the side of the Zamorin against Cochin. Sakthan Thampuran put an end to the institution of the Yogatirippad. Since then the numerous Namboothiri illams situated in Thrissur gradually became extinct. But even today there are a few Namboothiri illams in Thrissur and its suburbs reminding one of those old days when the Namboothiri Yogam of Thrissur along with the Perumanam Yogam exercised jurisdiction over a large portion of the present Thrissur taluk.

Sakthan Thampuran enjoyed good relations with the British authorities and was also a personal friend of Dharma Raja of Travancore. Sakthan Thampuran married twice. His first wife was a Nair lady from the reputed Vadakke Kuruppath family of Thrissur (several members of the Cochin Royal Family later took spouses from this family) whom he married when he was 30 years old. He is said to have had a daughter from this first wife. However, this Nethyar Amma (title of the consort of the Cochin Rajah) died soon after an unhappy marriage. Thereafter the Sakthan Thampuran remained single for a few decades, marrying again at the age of 52. The second wife of the Sakthan Thampuran was Chummukutty Nethyar Amma of the Karimpatta family and was a talented musician and dancer of Kaikottikalli. She was 17 at the time of her marriage with the Sakthan Thampuran. The marriage was without issue and within four years, Sakthan Thampuran died. In those days the widowed Nethyar Ammas did not have any special provisions from the state and hence Chummukutty, at the age of 21, returned to her ancestral home. His palace, Shakthan Thampuran Palace, in Thrissur is preserved as a monument and he was responsible for developing the Thrissur city and also making it the Cultural Capital of Kerala.

English Period (1805–1947)

The wave of nationalism and political consciousness which swept through the country since the early decades of this century has its repercussions in the Thrissur as well. Even as early as 1919 a Committee of the Indian National Congress was functioning in Thrissur.[27] In the Civil Disobedience Movement of 1921, several persons in Thrissur city and other places in the District took active part and courted arrest. Thrissur District can claim the honour of having been in the forefront of the country-wide movement for temple entry and abolition of untouchability. The famous Guruvayur Satyagraha is a memorable episode in the history of the national movement. The Government of Cochin under the guidance of R.K. Shanmughom Chetti followed a policy of conciliation. By degrees the public demand for the introduction of responsible Government in the State grew strong. In August 1938, Cochin announced a scheme for reforming the State legislature and introducing a system as per the Government of India Act of 1919 in the British Indian provinces. The administration of certain departments was entrusted to an elected member of the legislature to be nominated by the Maharaja.[27]

In the elections to the reformed legislature two political parties, viz, the Cochin State Congress and the Cochin Congress won 12 and 13 seats respectively. With the help of a few independents Ambat Sivarama Menon who was the leader of the Cochin Congress Party took up office as Minister under the scheme in June 1938. On his death in August 1938, Dr A.R. Menon was appointed as Minister. When the State Legislature passed a vote of non-confidence against him, Dr Menon resigned office on 25 February 1942 and was succeeded by T.K. Nair, Nair was in office until 11 July 1945. The introduction of diarchy did not satisfy the political aspirations of the people of Cochin. The idea of full responsible Government on the basis of adult franchise had caught their imagination. On 26 January 1941 a new political organization called the Cochin State Praja Mandal took shape on the initiative of a few young politicians under the leadership of V. R. Krishnan Ezhuthachan.[27]

The Quit India movement of 1942 has its echoes in the District. After the release of the leaders from jail in 1943, the Cochin State Praja Mandal pursued its organizational activities more vigorously. In the elections to the State Legislature in 1945 it won 12, of the 19 seats contested by its candidates. At the annual conference of the Praja Mandal held at Ernakulam in 1946 it was decided to start a statewide movement for the achievement of a responsible Government. The State Legislature was scheduled to meet on 29 July, and it was decided that the day should be observed all over the State as responsible Government day. In pursuance of this decision, meetings and demonstrations were held all over the State demanding the end of Dewan's rule and the transfer of full political power to the elected representatives of the people. The Maharaja of Cochin announced in August 1946 decision to transfer all departments of the State Government except Law and Order and Finance to the control of Ministers responsible to the State Legislature. In co-operation with other parties in the State Legislature, the Cochin State Praja Mandal decided to accept the offer. Consequently, the first popular Cabinet of Cochin consisting of Panampilly Govinda Menon, C.R. Iyyunni, K.Ayyappan and T.K. Nair assumed office. The first step towards the achievement of the goal of Aikyakerala was taken with the integration of Travancore Cochin States in July 1949. With the linguistic reorganization of States in India, in November 1956 the Kerala State came into existence.[27]

Post Independence era

In 1947, India gained independence from the British colonial rule. Cochin was the first princely state to join the Indian Union willingly. Post independence, E. Ikkanda Warrier became the first Prime Minister of Cochin. K.P.Madhavan Nair, P.T Jacob, C. Achutha Menon, Panampilly Govinda Menon were few of the other stalwarts who were in the forefront of the democratic movements. Then in 1949, Travancore-Cochin state came into being by the merger of Cochin and Travancore, with Parur T. K. Narayana Pillai as the first chief minister. Travancore-Cochin, was in turn merged with the Malabar district of the Madras State. Finally, the Government of India's 1 November 1956 States Reorganisation Act inaugurated a new state – Kerala – incorporating Travancore-Cochin, Malabar District, and the taluk of Kasargod, South Kanara.[31]

References

- "Catholic Syrian: God's Own Bank". Forbes India. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "A tour of heritage sites in Thrissur". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- S Hemachandran, "Monuments Embossing History", Kerala Calling, July 2007. (Retrieved on 24 January 2009)

- V V K Valath (1992). Keralathile Sthalacharithrangal: Thrissur Jilla,(Malayalam: കേരളത്തിലെ സ്ഥലചരിത്രങ്ങള്: തൃശൂർ ജില്ല) p.217. Kerala Sahithya Akadamy, Thrissur.

- "Students prepare manual on flora". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 4 March 2005. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "Search for India's ancient city". BBC. 11 June 2006. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "History of Kochi". Centre For Heritage Studies, India. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "Kerala Tourism". Muziris, A cultural tourist destination in kerala. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "Excavations highlight Malabar maritime heritage". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 April 2007. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "Hunting for Muziris". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 March 2004. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "Archaeologists stumble upon Muziris". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- http://www.samachaar.in/Delhi/Trade_links_of_Kerala_city_date_back_to_500_BC_19220/

- "Study points to 500 BC Kerala maritime activity". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 9 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://indiatoday.intoday.in/index.php?issueid=&id=3689&option=com_content&task=view§ionid=21

- "Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century". Paul Halsall. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- Thür, G. 1987. Hypotheken Urkunde eines Seedarlehens für eine Reise nach Muziris und Apographe für die Tetarte in Alexandria (zu P. Vindob. G. 40. 8222). Tyche 2:229–245.

- T.K. Joseph (1955). Six St. Thomases of South India. University of California. p. 27.

- "Nasrani Syrian Christians". Kuzhippallil.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- "World's second oldest mosque is in India". Bahrain tribune. Archived from the original on 6 July 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2006.

- "Cheraman Juma Masjid A Secular Heritage". Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "A mosque from a Hindu king". indiatravels. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2006.

- "Hindu patron of Muslim heritage site". iosworld.org. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2006.

- "Kalam to visit oldest mosque in sub-continent". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 23 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 November 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2006.

- Kerala.com (2007). "Kerala History". Archived from the original on 10 January 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- Pillai, Elamkulam Kunjan (1970). Studies in Kerala History.

- "History". Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Castanheda, p.272

- Mathew (1997: p.14)

- K.L. Bernard, Kerala History , pp.78–79

- Plunkett, R.; Cannon, T. (2001). Lonely Planet South India (2nd ed.). Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-86450-161-8. OCLC 1064959352.