Ring road

A ring road (also known as beltline, beltway, circumferential (high)way, loop or orbital) is a road or a series of connected roads encircling a town, city, or country. The most common purpose of a ring road is to assist in reducing traffic volumes in the urban centre, such as by offering an alternate route around the city for drivers who do not need to stop in the city core.

Nomenclature

.jpg.webp)

The name "ring road" is used for the majority of metropolitan circumferential routes in the European Union, such as the Berliner Ring, the Brussels Ring, the Amsterdam Ring, the Boulevard Périphérique around Paris and the Leeds Inner and Outer ring roads. Australia, Pakistan and India also use the term ring road, as in Melbourne's Western Ring Road, Lahore's Lahore Ring Road and Hyderabad's Outer Ring Road. In Canada the term is the most commonly used, with "orbital" also used, but to a much lesser extent.

In Europe, some ring roads, particularly those of motorway standard which are longer in length, are often known as "orbital motorways". Examples include the London Orbital (188 km) and Rome Orbital (68 km).

In the United States, many ring roads are called beltlines, beltways, or loops, such as the Capital Beltway around Washington, D.C. Some ring roads, such as Washington's Capital Beltway, use "Inner Loop" and "Outer Loop" terminology for directions of travel, since cardinal (compass) directions cannot be signed uniformly around the entire loop. The term 'ring road' is occasionally – and inaccurately – used interchangeably with the term 'bypass'.

Background

Bypasses around many large and small towns were built in many areas when many old roads were upgraded to four-lane status in the 1930s to 1950s, such as those along the Old National Road (now generally U.S. 40 or Interstate 70) in the United States, leaving the old road in place to serve the town or city, but allowing through travelers to continue on a wider, faster, and safer route.

Construction of fully circumferential ring roads has generally occurred more recently, beginning in the 1960s in many areas, when the U.S. Interstate Highway System and similar-quality roads elsewhere were designed. Ring roads have now been built around numerous cities and metropolitan areas, including cities with multiple ring roads, irregularly shaped ring roads, and ring roads made up of various other long-distance roads.

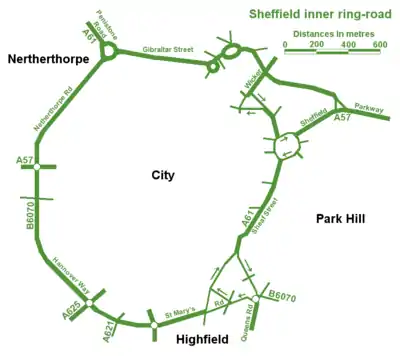

London has three ring roads (the London Orbital, the North and South Circular routes, and the Inner Ring Road). Other British cities have two (Birmingham, Leeds, Sheffield, Norwich and Glasgow). Columbus, OH and San Antonio, TX, in the United States, also has two, while Houston, Texas will have three official ring roads (not including the downtown freeway loop). Some cities have far more – Beijing, for example, has six ring roads, simply numbered in increasing order from the city center (though skipping #1), while Moscow has five, three innermost (Central Squares of Moscow, Boulevard Ring and Garden Ring) corresponding to the concentric lines of fortifications around the ancient city, and the two outermost (MKAD and Third Ring) built in the twentieth century, though, confusingly, the Third Ring was built last.

Geographical constraints can complicate the construction of a complete ring road. For example, the Baltimore Beltway in Maryland crosses Baltimore Harbor on a high arch bridge, and much of the partially completed Stockholm Ring Road in Sweden runs through tunnels or over long bridges. Some towns or cities on seacoasts or near rugged mountains cannot have a full ring road, such as Dublin's ring road; or, in the US, Interstate 287, mostly in New Jersey (bypassing New York City), or Interstate 495 around Boston, none of which completely circles these seaport cities.

In other cases, adjacency of international boundaries may prevent ring road completion. Construction of a true ring road around Detroit is effectively blocked by its location on the border with Canada; although constructing a route mostly or entirely outside city limits is technically feasible, a true ring around Detroit would necessarily pass through Canada, and so Interstate 275 and Interstate 696 together bypass but do not encircle the city. Sometimes, the presence of significant natural or historical areas limits route options, as for the long-proposed Outer Beltway around Washington, D.C., where options for a new western Potomac River crossing are limited by a nearly continuous corridor of heavily visited scenic, natural, and historical landscapes in the Potomac River Gorge and adjacent areas.

When referring to a road encircling a capital city, the term "beltway" can also have a political connotation, as in the American term "Inside the Beltway", derived metonymically from the Capital Beltway encircling Washington, D.C.

Impact

Ring roads have been criticised for inducing demand, leading to more car journeys being taken and thus higher levels of pollution being created. By creating easy access by car to large areas of land, they can also act as a catalyst for development, leading to urban sprawl and car-centric planning.[1] Ring roads have also been criticised for splitting communities and being difficult to navigate for pedestrians and cyclists.[2]

Examples of ring roads

Most orbital motorways (or beltways) are purpose-built major highways around a town or city, typically without either signals or road or railroad crossings. In the United States, beltways are commonly parts of the Interstate Highway System. Similar roads in the United Kingdom are often called "orbital motorways". Although the terms "ring road" and "orbital motorway" are sometimes used interchangeably, "ring road" often indicates a circumferential route formed from one or more existing roads within a city or town, with the standard of road being anything from an ordinary city street up to motorway level. An excellent example of this is London's North Circular/South Circular ring road.

In some cases, a circumferential route is formed by the combination of a major through highway and a similar-quality loop route that extends out from the parent road, later reconnecting with the same highway. Such loops not only function as a bypass for through traffic, but also to serve outlying suburbs. In the United States, an Interstate highway loop is usually designated by a three-digit number beginning with an even digit before the two-digit number of its parent interstate. Interstate spurs, on the other hand, generally have three-digit numbers beginning with an odd digit.

United States

Circumferential highways are prominent features in or near many large cities in the United States. In many cases, such as Interstate 285 (also known as the Perimeter) in Atlanta, Georgia, circumferential highways serve as a bypass while other highways pass directly through the city center. In other cases, a primary Interstate highway passes around a city on one side, with a connecting loop Interstate bypassing the city on the other side, together forming a circumferential route, as with I-93 and I-495 in the area of Lawrence, Massachusetts. However, if a primary Interstate passes through a city and a loop bypasses it on only one side (as in the Wilmington, Delaware, area), no fully circumferential route is provided.

Route numbering is challenging when a through highway and a loop bypass together form a circumferential ring road. Since neither of the highways involved is circumferential itself, either dual signage or two (or more) route numbers is needed. The history of signage on the Capital Beltway around Washington, D.C., is instructive here. Interstate 95, a major through highway along the U.S. East Coast, was originally planned as a through-the-city route there, with the Beltway encircling the city as I-495. The portion of I-95 entering the city from the south was soon completed (and so signed), primarily by adapting an existing major highway, but the planned extension of I-95 through residential areas northward to the Beltway was long delayed, and eventually abandoned, leaving the eastern portion of the Beltway as the best Interstate-quality route for through traffic.

This eastern portion of the Beltway was then redesignated from I-495 to I-95, leaving the I-495 designation only on the western portion, and the completed part of the planned Interstate inside the Beltway was redesignated as a spur, I-395. A few years later, the resulting confusion from different route numbers on the circumferential Beltway was resolved by restoring I-495 signage for the entire Beltway, with dual signage for I-95 for the highway's concurrent use as a through Interstate on its eastern portion.

The longest complete beltway in the United States is Sam Houston Tollway, a 88-mile (142 km) loop in Texas that forms a complete beltway around the Metro Houston area. [3]

Other major U.S. cities with such a beltway superhighway:

- Atlanta, Georgia—Interstate 285

- Athens, Georgia - Georgia State Route 10 Loop/Athens Perimeter

- Augusta, Georgia/North Augusta, South Carolina—Interstate 520, and Interstate 20

- Baltimore—Interstate 695 including the Francis Scott Key Bridge

- Boston—Route 128/Interstate 95 and Interstate 93/U.S. Route 1 form an inner beltway, and Interstate 495 forms an outer beltway

- Birmingham, Alabama—Interstate 459 and proposed/under construction Interstate 422

- Charlotte, North Carolina—Interstate 485, and Interstate 277

- Chicago—Interstate 294

- Cincinnati—Interstate 275

- Cleveland—Interstate 271 and Interstate 480

- Columbia, South Carolina—Interstate 26, Interstate 77, and Interstate 20

- Columbus, Ohio—Interstate 270

- Dallas—Downtown Circulator, Interstate 20/Interstate 635/Loop 12, and President George Bush Turnpike

- Denver—(Partial; see Note) Interstate 70, Colorado State Highway 470, and E-470 (Note: An incomplete beltway, likely permanent, due to underground plutonium contamination in the northwest quadrant)

- Des Moines, Iowa-Interstate 35/Interstate 80, U.S. Route 69, Iowa Highway 5

- Detroit—Interstate 275 and Interstate 696

- Dothan, Alabama−Ross Clark Circle; U.S. Route 231, U.S. Route 431, U.S. Route 84, and Alabama State Route 210

- El Paso, Texas – Loop 375

- Fort Wayne, Indiana—Interstate 69 and Interstate 469

- Fort Worth, Texas—Interstate 20/Interstate 820

- Greensboro, North Carolina—Interstate 85, Interstate 840, Interstate 73

- Houston—Interstate 610, Beltway 8, and the Grand Parkway.

- Indianapolis—Interstate 465

- Jacksonville, Florida—Interstate 295

- Kansas City, Kansas/Kansas City, Missouri—Interstate 435

- Lansing, Michigan—Interstate 96, Interstate 69, U.S Route 127 and Interstate 496

- Las Vegas—Interstate 215

- Los Angeles—Interstate 405

- Lubbock, Texas—Loop 289

- Memphis, Tennessee—Interstate 240 and Interstate 40 (Inner Beltway); Interstate 269 (Outer Beltway)

- Minneapolis/Saint Paul, Minnesota—Interstate 94, Interstate 494, and Interstate 694

- Nashville, Tennessee—Downtown Loop (Interstate 24, Interstate 40, and Interstate 65), Interstate 440, and Briley Parkway

- New York City—Interstate 287

- Norfolk, Virginia/Hampton Roads—Hampton Roads Beltway; Interstate 64 and Interstate 664

- Philadelphia—Interstate 476, Interstate 276 and Interstate 95 around Philadelphia

- Philadelphia/Camden—Interstate 676 and Schuylkill Expressway around Center City and Camden

- Philadelphia/Camden/Wilmington—Interstate 95 in PA/DE and Interstate 295

- Phoenix, Arizona—Arizona State Route 101 and Arizona State Route 202

- Pittsburgh—Interstate 79, the mainline Pennsylvania Turnpike and the Allegheny County belt system. (all de facto or, in the case of the latter, largely on surface streets) The Southern Beltway, which is currently under construction, will serve as a true beltway.

- Portland, Oregon—Interstate 405 and Interstate 205

- Raleigh, North Carolina—Interstate 540 (Triangle Expressway) and Interstate 440 (Raleigh Beltline)

- Richmond/Petersburg, Virginia—Interstate 295

- Saint Louis, Missouri—Interstate 255 and Interstate 270

- Salt Lake City—Interstate 215

- San Antonio—Downtown Circulator, Interstate 410, and Loop 1604

- San Diego—Interstate 805

- San Francisco Bay Area—Interstate 280 and Interstate 680

- Scranton, Pennsylvania—Interstate 81 and Interstate 476

- Seattle—Interstate 405

- Toledo, Ohio—Interstate 475 (Ohio), Interstate 75, The Ohio Turnpike and Interstate 280

There are other U.S. superhighway beltway systems that consist of multiple routes that require multiple interchanges and thus do not provide true ring routes. A designated example is the Capital Beltway around Harrisburg, Pennsylvania using Interstate 81, Interstate 83, and Pennsylvania Route 581.

Canada

Edmonton, Alberta has two ring roads. The first is a loose conglomeration of four major arterial roads with an average distance of 6 km (4 mi) from the downtown core. Yellowhead Trail forms the northern section, Wayne Gretzky Drive/75 Street forms the eastern section, Whitemud Drive forms the southern and longest section, and 170 Street forms the western and shortest section. Whitemud Drive is the only section that is a true controlled-access highway, while Yellowhead Trail and Wayne Gretzky Drive have interchanges and intersections and are therefore both limited-access roads. 170 Street and 75 Street are merely large arterial roads with intersections only.[4] The second and more prominent ring road is named Anthony Henday Drive; it circles the city at an average distance of 12 km (7.5 mi) from the downtown core. It is a freeway for its entire 78-kilometre (48 mi) length, and was built to reduce inner-city traffic congestion, created a bypass of Yellowhead Trail, and has improved the movement of goods and services across Edmonton and the surrounding areas. It was completed in October 2016 as the first free-flowing orbital road in Canada.[5][6]

Stoney Trail is a ring road that circles the majority of Calgary. The southwest portion of the freeway is currently under construction.[7]

Winnipeg, Manitoba has a ring road which is called the Perimeter Highway. It is designated as Manitoba Highway 101 on the north, northwest and east sides and as Manitoba Highway 100 on the south and southwest sides. The majority of it is a four-lane divided expressway. It has a second ring road, planned since the 1950s and not yet completed, called the Suburban Beltway. It consists of several roads -- Lagimodiere Blvd., Bishop Grandin Blvd., the Fort Garry Bridge, the Moray Bridge, William R Clement Parkway, Chief Peguis Trail and the Kildonan Bridge.

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan has a ring road named Circle Drive. It is designated as Saskatchewan Highway 16 on the east and north, and as Saskatchewan Highway 11 on the south, and simply as Circle Drive on the west.

Regina, Saskatchewan has a partial ring road that is named Ring Road; however, due to the city's urban growth since the road was originally constructed, it no longer functions as a true ring road and has instead come to be used partially for local arterial traffic. The Regina Bypass, a new partial ring road, has replaced it.

Hamilton, Ontario has the Lincoln M. Alexander Parkway, Ontario 403and the Red Hill Valley Parkway which form a ring on three sides.

Sudbury, Ontario has a partial ring road consisting of the Southwest and Southeast Bypasses segment of Ontario Highway 17, and the Northwest Bypass segment of Ontario Highway 144.

Europe

Most major cities in Europe are served by a ring road that either circles the inner core of their metropolitan areas or the outer borders of the city proper or both. In major transit hubs, such as the Île-de-France region surrounding Paris and the Frankfurt area, major national highways converge just outside city limits before forming one of several routes of an urban network of roads circling the city. Unlike in United States, route numbering is not a challenge on European ring roads as routes merge to form the single designated road. However, exit and road junction access can be challenging due to the complexity of other routes branching from or into the ring road.

One of the most renowned ring roads is the Vienna Ring Road (Ringstraße), a grand boulevard constructed in the mid-19th century and filled with representative buildings. Due to its unique architectural beauty and history, it has also been called the "Lord of the ring roads", and is declared by UNESCO as part of Vienna's World Heritage Site.[8][9]

Major European cities that are served by a ring road or ring road system:

- Amsterdam – A10 motorway

- Antwerp – R1

- Athens – Attiki Odos (Motorway A6)

- Barcelona – Ronda de Dalt and Ronda Litoral (inner city), B30 and B40 (metropolitan region)

- Belgrade – Belgrade bypass

- Berlin – Bundesautobahn 100 (inner city), Bundesautobahn 111 (city proper), Bundesautobahn 10 (inner metropolitan region)

- Birmingham – A4400 (Birmingham Queensway); A4540 (Birmingham Middleway); A4040 (Birmingham Outer Circle)

- Bologna – Tangenziale di Bologna (periphery half-ring road) and Viali di Circonvallazione (full and inner ring road: around the city center)

- Brussels – Petite ceinture (inner city), R22 (outer districts), Brussels Ring (city proper)

- Bucharest – Centura București

- Budapest – M0

- Caen – Périphérique

- Catania – Tangenziale di Catania

- Charleroi – R9 (inner city), R3 (inner metropolitan region)

- Cologne – Cologne Ring (inner city), Cologne Beltway (metropolitan region)

- Copenhagen – Ring 2, Ring 3, Ring 4, Motorring 3 and Motorring 4

- Dublin – M50 motorway

- Frankfurt – Bundesautobahn 66 and Bundesautobahn 661 (city proper), Frankfurter Kreuz system (inner metropolitan region)

- Glasgow – Glasgow Inner Ring Road (inner city)

- Hamburg – Inner Ring (inner city)

- Helsinki – Ring I, Ring III

- Herning – Messemotorvejen, Messemotorvejens forlængelse, Sindingvej, Midtjyske Motorvej

- Leeds - Leeds Inner Ring Road (inner city), Leeds Outer Ring Road (suburbs)

- London – London Inner Ring Road (inner city), North Circular Road and South Circular Road (inner suburbs), M25 motorway (metropolitan region)

- Lisbon – 2ª Circular (Inner City), IC17-CRIL (City Proper), IC18/A9-CREL (Metropolitan Region)

- Lyon – A7 autoroute and A46 autoroute (city proper)

- Ljubljana – Ljubljana Ring Road

- Madrid – M-30 (inner city), M-40 (inner metropolitan region), M-50 (outer metropolitan region, incomplete)

- Manchester – M60 motorway (inner metropolitan region)

- Milan – A4 motorway, A50 (West), A51 (East), A52 (North) and A58 (Outer Eastern) bypass roads, Circolare Esterna (periphery ring road), Circonvallazione (ring road around the centre), Cerchia Interna (ring road in the city centre)

- Minsk – M9

- Moscow – Boulevard Ring, Garden Ring, Third Ring Road, Moscow Ring Road (opened in 1961)

- Munich – Altstadtring (inner city), Bundesautobahn 99 (inner metropolitan region)

- Naples – Tangenziale di Napoli

- Oslo – Ring 1, Ring 2 and Ring 3

- Oxford – Oxford Ring Road

- Paris – Boulevard Périphérique (city proper), A86 autoroute (inner metropolitan region), Francilienne (tertiary ring road), Grand contournement de Paris (metropolitan region)

- Padua – GRAP

- Palma de Mallorca – Ma-20 (Vía de Cintura)

- Prague – outer - D0 and inner Městský okruh

- Rennes – Rocade de Rennes (city proper)

- Rome – Grande Raccordo Anulare

- Sofia – Sofia Ring Road

- Saint-Petersburg – Saint Petersburg Ring Road

- Tampere – Tampere Ring Road

- Thessaloniki – Thessaloniki Inner Ring Road

- Venice – Tangenziale di Venezia

- Vienna – Vienna Ring Road (inner city), Vienna Beltway (outer districts)

- Vigo – VG-20 (Vigo Ring Road)

- Warsaw – Expressway S2, Expressway S7, Expressway S8, Expressway S17

- Wroclaw - Outer ring: Autostrada A4, Autostrada A8, Expressway S8, Wroclaw Eastern Bypass (in construction). Inner ring: National road 5, National road 94

- Zagreb – Zagreb bypass

In Iceland, there is a 1,332 km ring road, called the ring road (or Route 1), around most of the island (excluding the Westfjords). Most of the country's settlements are on or near this road.

Asia

Major Asian cities that are served by a ring road or ring road system:

- Ahmedabad, India - Sardar Patel Ring Road

- Ankara, Turkey - Otoyol 20

- Bangkok, Thailand - Ratchadaphisek Road (Inner Ring Road) and Kanchanaphisek Road (Outer Ring Road)

- Beijing, China - six ring roads encircling the city.

- Bengaluru, India - Inner Ring Road andOuter Ring Road

- Delhi, India - Inner Ring Road, Delhi and Outer Ring Road, Delhi

- George Town, Malaysia - George Town Inner Ring Road, Penang Middle Ring Road

- Hong Kong, Hong Kong - Route 9 (New Territories Circular Road)

- Hyderabad, India - Outer Ring Road, Hyderabad

- Jakarta, Indonesia - Jakarta Inner Ring Road, Jakarta Outer Ring Road, Jakarta Outer Ring Road 2

- Kathmandu, Nepal - Kathmandu Ringroad

- Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia - Kuala Lumpur Inner Ring Road, Kuala Lumpur Middle Ring Road 1, Kuala Lumpur Middle Ring Road 2, Kuala Lumpur Outer Ring Road

- Lahore, Pakistan - Lahore Ring Road

- Medina, Saudi Arabia - King Faisal Road (1st Ring Road) and King Abdullah Road (2nd Ring Road)

- Peshawar, Pakistan - Peshawar Ring Road

- Riyadh, Saudi Arabia - Riyadh Ring Road

- Sendai, Japan - Gurutto Sendai

- Seoul, South Korea - Seoul Ring Expressway

- Shanghai, China - Inner Ring Road, Middle Ring Road, S20 Outer Ring Expressway, G1501 Shanghai Ring Expressway

- Singapore, Singapore - Outer Ring Road System

- Tianjin, China - Inner, Middle and Outer Ring Roads

- Tokyo, Japan - C1 Inner Circular Expressway, C2 Central Circular Expressway, C3 Gaikan Expressway, C4 Ken-Ō Expressway, CA Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line/B Bayshore Route, Yokohama Ring Expressway, Japan National Route 16, Japan National Route 298, Japan National Route 357, Japan National Route 468

Africa

- Addis Ababa, Ethiopia - Addis Ababa Ring Road

- Cairo, Egypt - Ring Road (Cairo)

- Johannesburg, South Africa - Johannesburg Ring Road

- Nairobi, Kenya - Ring road, Kisumu City, Kenya Ring road

References

- Snell, Steven (7 November 2013). "The Irony of Ring Roads". Planetizen. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- "Are these the worst ring roads in England?". BBC News. 5 April 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- "Final Section of Sam Houston Tollway Opens". Houston: KTRK-TV. 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- "Inner Ring Road". Connect2Edmonton. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Northeast Anthony Henday Drive". www.northeastanthonyhenday.com. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Northeast Anthony Henday Drive". Alberta Transportation. 2016. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

The northeast leg of Anthony Henday Drive opened on October 1, 2016, after five years of construction...

- Google (1 December 2016). "Length of Stoney Trail" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Malathronas, John (24 April 2015). "Vienna's Ringstrasse celebrates 150 years". edition.cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Historic Centre of Vienna". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 15 September 2016.