Tetrazepam

Tetrazepam[1] (is marketed under the following brand names, Clinoxan, Epsipam, Myolastan, Musaril, Relaxam and Spasmorelax) is a benzodiazepine derivative with anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, muscle relaxant and slightly hypnotic properties. It was formerly used mainly in Austria, France, Belgium, Germany and Spain to treat muscle spasm, anxiety disorders such as panic attacks, or more rarely to treat depression, premenstrual syndrome or agoraphobia. Tetrazepam has relatively little sedative effect at low doses while still producing useful muscle relaxation and anxiety relief. The Co-ordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures-Human (CMD(h)) endorsed the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) recommendation to suspend the marketing authorisations of tetrazepam-containing medicines across the European Union (EU) in April 2013.[2] The European Commission has confirmed the suspension of the marketing authorisations for Tetrazepam in Europe because of cutaneous toxicity, effective from the 1 August 2013.[3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 3–26 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.749 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

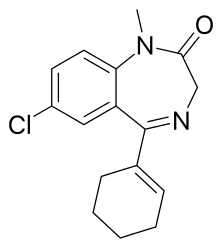

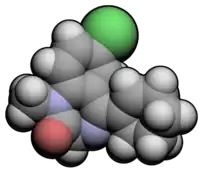

| Formula | C16H17ClN2O |

| Molar mass | 288.77 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Delayed type 4 allergic hypersensitivity reactions including maculopapular exanthema, erythematous rash, urticarial eruption, erythema multiforme, photodermatitis, eczema and Stevens–Johnson syndrome can occasionally occur as a result of tetrazepam exposure. These hypersensitivity reactions to tetrazepam share no cross-reactivity with other benzodiazepines.[4]

Availability

The indicated adult dose for muscle spasm is 25 mg to 150 mg per day, increased if necessary to a maximum of 300 mg per day, in divided doses. Tetrazepam is not generally recommended for use in children, except on the advice of a specialist.

Tetrazepam is only available in one strength and formulation, 50 mg tablets. The benzodiazepine equivalent of tetrazepam is approximately 100 mg of tetrazepam = 10 mg of diazepam.[7]

Adverse effects

Allergic reactions to tetrazepam occasionally occur involving the skin.[4]

Allergic reactions can develop to tetrazepam[8][9] and it is considered to be a potential allergen.[10][11] Drug rash and drug-induced eosinophilia with systemic symptoms is a known complication of tetrazepam exposure.[12][13] These hypersensitive allergic reactions can be of the delayed type.[14][15][16]

Toxic epidermal necrolysis has occurred from the use of tetrazepam[17][18] including at least one reported death.[19] Stevens–Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme has been reported from use of tetrazepam. Cross-reactivity with other benzodiazepines does not typically occur in such patients.[20][21][22] Exanthema[23] and eczema may occur.[24] The lack of cross-reactivity with other benzodiazepines is believed to be due to the molecular structure of tetrazepam.[25][26] Photodermatitis[27] and phototoxicity have also been reported.[28] Occupational contact allergy can also develop from regularly handling tetrazepam.[29][30] Airborne contact dermatitis can also occur as an allergy which can develop from occupational exposure.[31]

Patch testing has been used successfully to demonstrate tetrazepam allergy.[32][33] Oral testing can also be used. Skin prick tests are not always accurate and may produce false negatives.[34]

Drowsiness is a common side effect of tetrazepam.[35] A reduction in muscle force can occur.[36] Myasthenia gravis, a condition characterised by severe muscle weakness is another potential adverse effect from tetrazepam.[37] Cardiovascular and respiratory adverse effects can occur with tetrazepam similar to other benzodiazepines.[26]

Tolerance, dependence and withdrawal

Prolonged use, as with all benzodiazepines, should be avoided, as tolerance occurs and there is a risk of benzodiazepine dependence and a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome after stopping or reducing dosage.[26]

Overdose

Tetrazepam, like other benzodiazepines is a drug which is very frequently present in cases of overdose. These overdoses are often mixed overdoses, i.e. a mixture of other benzodiazepines or other drug classes with tetrazepam.[38][39]

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[40]

Pharmacology

Tetrazepam is an unusual benzodiazepine in its molecular structure as it has cyclohexenyl group which has substituted the typical 5-phenyl moiety seen in other benzodiazepines.[41] Tetrazepam, is rapidly absorbed after oral administration, within 45 mins and reaches peak plasma levels in less than 2 hours. It is classed as an intermediate acting benzodiazepine with an elimination half-life of approximately 15 hours. It is primarily metabolised to the inactive metabolites 3-hydroxy-tetrazepam and norhydroxytetrazepam.[41][42] The pharmacological effects of tetrazepam are significantly less potent when compared against diazepam, in animal studies.[43] Tetrazepam is a benzodiazepine site agonist and binds unselectively to type 1 and type 2 benzodiazepine site types as well as to peripheral benzodiazepine receptors.[44] The muscle relaxant properties of tetrazepam are most likely due to a reduction of calcium influx.[45] Small amounts of diazepam as well as the active metabolites of diazepam are produced from metabolism of tetrazepam.[46][47] The metabolism of tetrazepam has led to false accusations of prisoners prescribed tetrazepam of taking illicit diazepam; this can lead to increased prison sentences for prisoners.[41]

Abuse

Tetrazepam as with other benzodiazepines is sometimes abused. It is sometimes abused to incapacitate a victim in order to carry out a drug-facilitated crime.[48] or abused in order to achieve a state of intoxication.[49] Tetrazepam's abuse for to carry out drug facilitated crimes may be less however, than other benzodiazepines due to its reduced hypnotic properties.[50]

References

- NL Patent 6600095

- Recommendation to suspend tetrazepam-containing medicines endorsed by CMDh, European Medicines Agency, published 29 April 2013

- Ruhen der Zuhlassung aller Tetrazepam-haltiger Arzneimittel, Sanofi-Avensis Deutschland GmbH (German), published June 2013

- Thomas E, Bellón T, Barranco P, Padial A, Tapia B, Morel E, et al. (2008). "Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to tetrazepam" (PDF). Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 18 (2): 119–22. PMID 18447141.

- Simiand J, Keane PE, Biziere K, Soubrie P (January 1989). "Comparative study in mice of tetrazepam and other centrally active skeletal muscle relaxants". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 297: 272–85. PMID 2567153.

- Perez-Guerrero C, Herrera MD, Marhuenda E (November 1996). "Relaxant effect of tetrazepam on rat uterine smooth muscle: role of calcium movement". The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 48 (11): 1169–73. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1996.tb03915.x. PMID 8961167. S2CID 38144317.

- "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- Camarasa JG, Serra-Baldrich E (April 1990). "Tetrazepam allergy detected by patch test". Contact Dermatitis. 22 (4): 246. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1990.tb01587.x. PMID 2140761. S2CID 26973793.

- Collet E, Dalac S, Morvan C, Sgro C, Lambert D (April 1992). "Tetrazepam allergy once more detected by patch test". Contact Dermatitis. 26 (4): 281. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00259.x. PMID 1356710. S2CID 43750783.

- Ortiz-Frutos FJ, Alonso J, Hergueta JP, Quintana I, Iglesias L (July 1995). "Tetrazepam: an allergen with several clinical expressions". Contact Dermatitis. 33 (1): 63–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00462.x. PMID 7493477. S2CID 41533643.

- Del Pozo MD, Blasco A, Lobera T (November 1999). "Tetrazepam allergy". Allergy. 54 (11): 1226–7. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00362.x. PMID 10604563. S2CID 46139378.

- Dinić-Uzurov V, Lalosević V, Milosević I, Urosević I, Lalosević D, Popović S (November 2007). "[Current differential diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome]". Medicinski Pregled. 60 (11–12): 581–6. doi:10.2298/MPNS0712581D. PMID 18666600.

- Bachmeyer C, Assier H, Roujeau JC, Blum L (July 2008). "Probable drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome related to tetrazepam". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 22 (7): 887–9. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02490.x. PMID 18031497. S2CID 12775035.

- Blanco R, Díez-Gómez ML, Gala G, Quirce S (November 1997). "Delayed hypersensitivity to tetrazepam". Allergy. 52 (11): 1146–7. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb00194.x. PMID 9404574. S2CID 5381089.

- Ortega NR, Barranco P, López Serrano C, Romualdo L, Mora C (February 1996). "Delayed cell-mediated hypersensitivity to tetrazepam". Contact Dermatitis. 34 (2): 139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02147.x. PMID 8681544. S2CID 46147524.

- Kämpgen E, Bürger T, Bröcker EB, Klein CE (November 1995). "Cross-reactive type IV hypersensitivity reactions to benzodiazepines revealed by patch testing". Contact Dermatitis. 33 (5): 356–7. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb02060.x. PMID 8565501. S2CID 23398517.

- Delesalle F, Carpentier O, Guatier S, Delaporte E (April 2006). "Toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by tetrazepam". International Journal of Dermatology. 45 (4): 480. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02654.x. PMID 16650186. S2CID 221815580.

- Wolf R, Orion E, Davidovici B (October 2006). "Toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by tetrazepam". International Journal of Dermatology. 45 (10): 1260–1. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03061.x. PMID 17040464. S2CID 221815889.

- Lagnaoui R, Ramanampamonjy R, Julliac B, Haramburu F, Ticolat R (March 2001). "[Fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with tetrazepam". Therapie. 56 (2): 187–8. PMID 11471372.

- Pirker C, Misic A, Brinkmeier T, Frosch PJ (September 2002). "Tetrazepam drug sensitivity -- usefulness of the patch test". Contact Dermatitis. 47 (3): 135–8. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470302.x. PMID 12492544. S2CID 5932398.

- Sánchez I, García-Abujeta JL, Fernández L, Rodríguez F, Quiñones D, Duque S, et al. (2 March 1998). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome from tetrazepam". Allergologia et Immunopathologia. 26 (2): 55–7. PMID 9645262.

- Rodríguez Vázquez M, Ortiz de Frutos J, del Río Reyes R, Iglesias Díez L (September 2000). "[Erythema multiforme by tetrazepam]". Medicina Clinica. 115 (9): 359. doi:10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71559-4. PMID 11093904.

- Ghislain PD, Roussel S, Bouffioux B, Delescluse J (December 2000). "[Tetrazepam (Myolastan)-induced exanthema: positive patch tests in 2 cases]". Annales de Dermatologie et de Venereologie. 127 (12): 1094–6. PMID 11173688.

- Breuer K, Worm M, Skudlik C, Schröder C, John SM (October 2009). "Occupational airborne contact allergy to tetrazepam in a geriatric nurse". Journal of the German Society of Dermatology. 7 (10): 896–8. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07096.x. PMID 19453384. S2CID 29339528.

- Barbaud A, Girault PY, Schmutz JL, Weber-Muller F, Trechot P (July 2009). "No cross-reactions between tetrazepam and other benzodiazepines: a possible chemical explanation". Contact Dermatitis. 61 (1): 53–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01558.x. PMID 19659970. S2CID 205813960.

- Cabrerizo Ballesteros S, Méndez Alcalde JD, Sánchez Alonso A (2007). "Erythema multiforme to tetrazepam" (PDF). Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 17 (3): 205–6. PMID 17583114.

- Quiñones D, Sanchez I, Alonso S, Garcia-Abujeta JL, Fernandez L, Rodriguez F, et al. (August 1998). "Photodermatitis from tetrazepam". Contact Dermatitis. 39 (2): 84. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05840.x. PMID 9746190. S2CID 40771488.

- Schwedler S, Mempel M, Schmidt T, Abeck D, Ring J (1998). "Phototoxicity to tetrazepam - A new adverse reaction". Dermatology. 197 (2): 193–4. PMID 9840980.

- Choquet-Kastylevsky G, Testud F, Chalmet P, Lecuyer-Kudela S, Descotes J (June 2001). "Occupational contact allergy to tetrazepam". Contact Dermatitis. 44 (6): 372. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.440609-7.x. PMID 11417526.

- Lepp U, Zabel P, Greinert U (November 2003). "Occupational airborne contact allergy to tetrazepam". Contact Dermatitis. 49 (5): 260–1. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2003.0225c.x. PMID 14996051. S2CID 11238687.

- Ferran M, Giménez-Arnau A, Luque S, Berenguer N, Iglesias M, Pujol RM (March 2005). "Occupational airborne contact dermatitis from sporadic exposure to tetrazepam during machine maintenance". Contact Dermatitis. 52 (3): 173–4. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.0548o.x. PMID 15811045. S2CID 30499424.

- Barbaud A, Gonçalo M, Bruynzeel D, Bircher A (December 2001). "Guidelines for performing skin tests with drugs in the investigation of cutaneous adverse drug reactions". Contact Dermatitis. 45 (6): 321–8. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.450601.x. PMID 11846746. S2CID 10780935.

- Barbaud A, Trechot P, Reichert-Penetrat S, Granel F, Schmutz JL (April 2001). "The usefulness of patch testing on the previously most severely affected site in a cutaneous adverse drug reaction to tetrazepam". Contact Dermatitis. 44 (4): 259–60. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.440409-15.x. PMID 11336014. S2CID 40786622.

- Sánchez-Morillas L, Laguna-Martínez JJ, Reaño-Martos M, Rojo-Andrés E, Ubeda PG (2008). "Systemic dermatitis due to tetrazepam" (PDF). Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 18 (5): 404–6. PMID 18973107.

- Rode G, Maupas E, Luaute J, Courtois-Jacquin S, Boisson D (May 2003). "[Medical treatment of spasticity]". Neuro-Chirurgie. 49 (2–3 Pt 2): 247–55. PMID 12746699.

- Lobisch M, Schaffler K, Wauschkuhn H, Nickel B (March 1996). "[Clinical pilot study of the myogenic effects of flupirtine in comparison to tetrazepam and placebo]". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 46 (3): 293–8. PMID 8901152.

- Vargas Ortega I, Canora Lebrato J, Díez Ruiz A, Rico Irles J (December 2000). "[Myasthenia gravis after tetrazepam treatment]". Anales de Medicina Interna. 17 (12): 669. doi:10.4321/s0212-71992000001200016. PMID 11213590.

- Zevzikovas A, Bertulyte A, Dirse V, Ivanauskas L (2003). "[Determination of benzodiazepine derivatives mixture by high performance liquid chromatography]". Medicina. 39 Suppl 2: 30–6. PMID 14617855.

- Zevzikovas A, Kiliuviene G, Ivanauskas L, Dirse V (2002). "[Analysis of benzodiazepine derivative mixture by gas-liquid chromatography]" (PDF). Medicina (in Lithuanian). 38 (3): 316–20. PMID 12474705.

- Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, et al. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Pavlic M, Libiseller K, Grubwieser P, Schubert H, Rabl W (May 2007). "Medicolegal aspects of tetrazepam metabolism". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 121 (3): 169–74. doi:10.1007/s00414-006-0118-6. PMID 17021899. S2CID 32405914.

- Baumgärtner MG, Cautreels W, Langenbahn H (1984). "Biotransformation and pharmacokinetics of tetrazepam in man". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 34 (6): 724–9. PMID 6148954.

- Keane PE, Simiand J, Morre M, Biziere K (May 1988). "Tetrazepam: a benzodiazepine which dissociates sedation from other benzodiazepine activities. I. Psychopharmacological profile in rodents". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 245 (2): 692–8. PMID 2896794.

- Keane PE, Bachy A, Morre M, Biziere K (May 1988). "Tetrazepam: a benzodiazepine which dissociates sedation from other benzodiazepine activities. II. In vitro and in vivo interactions with benzodiazepine binding sites". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 245 (2): 699–705. PMID 2896795.

- Pérez-Guerrero C, Suárez J, Herrera MD, Marhuenda E (May 1997). "Spasmolytic effects of tetrazepam on rat duodenum and guinea-pig ileum". Pharmacological Research. 35 (5): 493–7. doi:10.1006/phrs.1997.0173. PMID 9299217.

- Baumann A, Lohmann W, Schubert B, Oberacher H, Karst U (April 2009). "Metabolic studies of tetrazepam based on electrochemical simulation in comparison to in vivo and in vitro methods". Journal of Chromatography A. 1216 (15): 3192–8. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2009.02.001. PMID 19233363.

- Schubert B, Pavlic M, Libiseller K, Oberacher H (December 2008). "Unraveling the metabolic transformation of tetrazepam to diazepam with mass spectrometric methods". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 392 (7–8): 1299–308. doi:10.1007/s00216-008-2447-4. PMID 18949465. S2CID 10967477.

- Concheiro M, Villain M, Bouchet S, Ludes B, López-Rivadulla M, Kintz P (October 2005). "Windows of detection of tetrazepam in urine, oral fluid, beard, and hair, with a special focus on drug-facilitated crimes". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 27 (5): 565–70. doi:10.1097/01.ftd.0000164610.14808.45. PMID 16175127. S2CID 45605607.

- Kintz P, Villain M, Concheiro M, Cirimele V (June 2005). "Screening and confirmatory method for benzodiazepines and hypnotics in oral fluid by LC-MS/MS". Forensic Science International. 150 (2–3): 213–20. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.12.040. PMID 15944062.

- Laloup M, Fernandez M, Wood M, Maes V, De Boeck G, Vanbeckevoort Y, Samyn N (August 2007). "Detection of diazepam in urine, hair and preserved oral fluid samples with LC-MS-MS after single and repeated administration of Myolastan and Valium". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 388 (7): 1545–56. doi:10.1007/s00216-007-1297-9. PMID 17468852. S2CID 19256926.