Area of freedom, security and justice

The area of freedom, security and justice (AFSJ) is a collection of home affairs and justice policies designed to ensure security, rights and free movement within the European Union (EU). Areas covered include the harmonisation of private international law, extradition arrangements between member states, policies on internal and external border controls, common travel visa, immigration and asylum policies and police and judicial cooperation.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

|

As internal borders have been removed within the EU, cross-border police cooperation has had to increase to counter cross-border crime. Some notable projects related to the area are the European Arrest Warrant, the Schengen Area and Frontex patrols.

Organisation

The area comes under the purview of the European Commissioner for Justice, Fundamental Rights and Citizenship and the European Commissioner for Home Affairs. They deal with the following matters: EU citizenship; combating discrimination, drugs, organised crime, terrorism, human trafficking; free movement of people, asylum and immigration; judicial cooperation in civil and criminal matters; police and customs cooperation; and these matters in the acceding countries.[1]

The relevant European Commission departments are the DG for Justice and the DG Home Affairs. However, there are also Eurojust and Europol, which develop judicial and police cooperation respectively. Related to the latter there is also the European Police College, the European Police Chiefs Task Force and Frontex.

Actions

Over the years, the EU has developed a wide competence in the area of justice and home affairs. To this end, agencies have been established that co-ordinate associated actions: Europol for co-operation of police forces,[2] Eurojust for co-operation between prosecutors,[3] and Frontex for co-operation between border control authorities.[4] The EU also operates the Schengen Information System[5] which provides a common database for police and immigration authorities throughout the borderless Schengen Area.

Furthermore, the Union has legislated in areas such as extradition (such as the European Arrest Warrant),[6] family law,[7] asylum law,[8] and criminal justice.[9] Prohibitions against sexual and nationality discrimination have a long standing in the treaties.[10] In more recent years, these have been supplemented by powers to legislate against discrimination based on race, religion, disability, age, and sexual orientation.[11] By virtue of these powers, the EU has enacted legislation on sexual discrimination in the work-place, age discrimination, and racial discrimination.[12]

European crimes

In 2006, a toxic waste spill off the coast of Côte d'Ivoire, from a European ship, prompted the Commission to look into legislation against toxic waste. Environment Commissioner Stavros Dimas stated that "Such highly toxic waste should never have left the European Union". With countries such as Spain not even having a law against shipping toxic waste Franco Frattini, the Justice, Freedom and Security Commissioner, proposed with Dimas to create criminal sentences for "ecological crimes". His right to do this was contested in 2005 at the Court of Justice resulting in a victory for the Commission. That ruling set a precedent that the Commission, on a supranational basis, may legislate in criminal law. So far though, the only other use has been the intellectual property rights directive.[13] Motions were tabled in the European Parliament against that legislation on the basis that criminal law should not be an EU competence, but were rejected at vote.[14] However, in October 2007 the Court of Justice ruled the Commission could not propose what the criminal sanctions could be, only that there must be some.[15]

The European Commission has listed seven offences that become European crimes.[16] The seven crimes announced by the Commission are counterfeiting euro notes and coins; credit card and cheque fraud; money laundering; people-trafficking; computer hacking and virus attacks; corruption in the private sector; and marine pollution. The possible future EU crimes are racial discrimination and incitement to racial hatred;[17] organ trade; and corruption in awarding public contracts. It will also set out the level of penalty, such as length of prison sentence, that would apply to each crime.[18]

History

The first steps in security and justice cooperation within the EU began in 1975 when the TREVI group was created, composed of member states' justice and home affairs ministers. The first real cooperation was the signing of the Schengen Implementing Convention in 1990 which opened up the EU's internal borders and established the Schengen Area. In parallel the Dublin Regulation furthered police cooperation.[19]

Cooperation on policies such as immigration and police cooperation was formally introduced in the Maastricht Treaty which established Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) as one of the EU's 'three pillars'. The Justice and Home Affairs pillar was organised on an intergovernmental basis with little involvement of the EU supranational institutions such as the European Commission and the European Parliament. Under this pillar the EU created the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) in 1993 and Europol in 1995. In 1997 the EU adopted an action plan against organised crime and established the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC). In 1998 the European Judicial Network in criminal matters (EJN) was established.[19]

The idea of an area of freedom, security and justice was introduced in May 1999, in the Treaty of Amsterdam, which stated that the EU must "maintain and develop the Union as an area of freedom, security and justice, in which the free movement of persons is assured in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external border controls, asylum, immigration and the prevention and combating of crime."[20] The first work programme putting this provision into effect was agreed at Tampere, Finland in October 1999. Subsequently, the Hague programme, agreed in November 2004, set further objectives to be achieved between 2005 and 2010.[21]

The Treaty of Amsterdam also transferred the areas of asylum, immigration and judicial cooperation in civil matters from the JHA to the European Community pillar, the remainder being renamed Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC).[22]

During this time further advancements were made. In 2000 the European Police College was created along with numerous conventions and agreements. The Treaty of Nice enshrined Eurojust in the EU treaties and in 2001 and 2002 Eurojust, Eurodac, the European Judicial Network in Civil and Commercial Matters (EJNCC) and European Crime Prevention Network (EUCPN) were established. In 2004 the EU appointed an anti-terrorism coordinator in response to the 2004 Madrid train bombings and the European Arrest Warrant (agreed in 2002) entered into force.[19]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The 2009 Treaty of Lisbon abolished the pillar structure, reuniting the areas separated at Amsterdam. The European Parliament and Court of Justice gained a say over the whole area while the Council changed to majority voting for the remaining PJCC matters. The Charter of Fundamental Rights also gained legal force and Europol was brought within the EU's legal framework.[23] As the Treaty of Lisbon came into force, the European Council adopted the Stockholm Programme to provide EU action on developing the area over the following five years.[21]

Justice

There has been criticism that the EU's activities have been too focused on security and not on justice.[24][25] For example, the EU created the European Arrest Warrant but no common rights for defendants arrested under it. With the strengthened powers under Lisbon, the second Barroso Commission created a dedicated commissioner for justice (previously combined with security under one portfolio) who is obliging member states to provide reports on their implementation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights. Furthermore, the Commission is putting forward proposals for common rights for defendants (such as interpretation), minimum standards for prison conditions and ensure that victims of crime are taken care of properly wherever they are in the EU. This is intended to create a common judicial area where each system can be sure of trusting each other.[26]

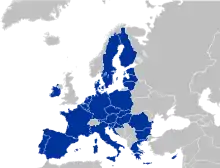

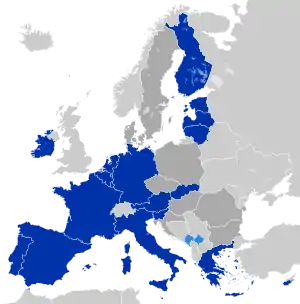

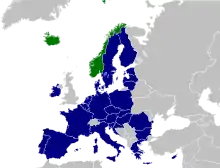

Opt-outs

Denmark and Ireland have various opt-outs from the border control, asylum policy, police and judicial cooperation provisions that are part of the area of freedom, security and justice. While Ireland has opt-ins that allows it to participate in legislation on a case-by-case basis, Denmark is fully outside the area of freedom, security and justice.

Denmark has nonetheless been fully implementing the Schengen acquis since 25 March 2001, but on an intergovernmental basis.[27]

The United Kingdom (a former EU member state which had an opt-out like Ireland) applied to participate in several areas of the Schengen acquis, including the police and judicial cooperation provisions, in March 1999.[28] Their request was approved by a Council Decision in 2000[29] and fully implemented by a Decision of the Council of the EU with effect from 1 January 2005.[30]

While Ireland also applied to participate in the police and judicial cooperation provisions of the Schengen acquis in June 2000,[28] and were approved by a Council Decision in 2002,[31] this has not been implemented.[32]

Broadening security and safety perspective

The European Union's growing role in coordinating internal security and safety policies is only partly captured by looking at policymaking within the area of freedom, security and justice. Across the EU's other (former) pillars, initiatives related to food security, health safety, infrastructure protection, counter-terrorism and energy security can be found. New perspectives and concepts have been introduced to examine the EU's wider internal security role for the EU, such as the EU's "protection policy space"[33] or internal "security governance".[34] Furthermore, EU cooperation not covered by a limited lens of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice—namely EU cooperation during urgent emergencies[35] and complex crises[36]—has received a growing amount of attention.

There have been proposals by the European Commission to upgrade the border agency Frontex, which is responsible for overseeing the security of the EU's external borders.[37] This new body, called the European Border and Coastguard Agency, would involve having a pool of armed guards, drawn from different EU member states, that can be dispatched to EU countries at three days' notice.[38] The European Border and Coastguard Agency would function more in a supervisory capacity.[39] The border agencies of host countries would still retain day-to-day control,[40] and the personnel from the new agency would be required to submit to the direction of the country where they are deployed.[41] However, interventions could potentially happen against the wishes of a host country.[42] They include instances such as "disproportionate migratory pressure" occurring on a country's border.[43] For this intervention to happen, the new border agency would have to gain consent from the European Commission.[44] Under these proposals, border guards would be allowed to carry guns.[45] The agency would also be able to acquire its own supply of patrol ships and helicopters.[46]

See also

- Citizenship of the European Union

- Directorate-General for Justice, Freedom and Security (European Commission)

- Eurojust

- European Commissioner for Home Affairs

- European Commissioner for Justice, Fundamental Rights and Citizenship

- European Police College

- European Public Prosecutor

- European Survey on Crime and Safety (EU ICS)

- European Union law

- Europol

- Former European Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security

- Four Freedoms (European Union)

- Schengen Agreement

- United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute

- Mechanism for Cooperation and Verification

- European Investigation Order

- G6 (Group of Six)

- Salzburg Forum

References

- Summaries of EU legislation: Justice, freedom and security, Europa (web portal), accessed 22 March 2010

- "European police office now in full swing". Europa web portal. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- "Eurojust coordinating cross-border prosecutions at EU level". Europa web portal. Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- Frontex. "What is Frontex?". Europa web portal. Archived from the original on 23 August 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- "Abolition of internal borders and creation of a single EU external frontier". Europa web portal. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- "European arrest warrant replaces extradition between EU Member States". Europa web portal. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- "Jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in matrimonial matters and in matters of parental responsibility (Brussels II)". Europa web portal. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- "Minimum standards on the reception of applicants for asylum in Member States". Europa web portal. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- "Specific Programme: 'Criminal Justice'". Europa web portal. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- See Articles 157 (ex Article 141) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Eur-lex.europa.eu

- See Article 2(7) of the Treaty of Amsterdam. Eur-lex.europa.eu

- Council Directive 2000/43/EC of 29 June 2000 implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin (OJ L 180, 19 July 2000, p. 22–26); Council Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000 establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation (OJ L 303, 2 December 2000, p. 16–22).

- Charter, David (2007). "A new legal environment". E!Sharp. People Power Process. pp. 23–5.

- Gargani, Giuseppe (2007). "Intellectual property rights: criminal sanctions to fight piracy and counterfeiting". European Parliament. Retrieved 30 June 2007.

- Mahony, Honor (23 October 2007). "EU court delivers blow on environment sanctions". EU Observer. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- "Judicial cooperation". European Commission - European Commission.

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_1655

- "The Times & The Sunday Times". thetimes.co.uk.

- Area of Freedom, Security and Justice, European Parliament, accessed 22 March 2010

- Article 1(5) of the Amsterdam Treaty.

- Strengthening the European Union as an area of freedom, security and justice, European Commission July 2008, accessed 16 November 2010

- Glossary: Area of freedom, security and justice Europa (web portal), accessed 22 March 2010

- Can the EU achieve an area of freedom, security and justice?, EurActive October 2003, accessed 22 March 2010

- Verbeet, Markus (19 March 2008) Interview with EU Justice Commissioner Franco Frattini: 'The Problem Is not Data Storage, It's Terrorism' Der Spiegel, accessed 22 March 2010

- European Arrest Warrant does not overrule human rights Archived 6 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Sarah Ludford 2 June 2009, accessed 22 March 2010

- Engerer, Cyrus (22 March 2010) Justice across Borders: Freedom, security and justice in the EU, Malta Independent Online, accessed 22 March 2010

- "The Schengen Agreement". 12 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "The Schengen area and cooperation". Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "2000/365/EC: Council Decision of 29 May 2000 concerning the request of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to take part in some of the provisions of the Schengen acquis". Official Journal of the European Communities. 131: 43–47. 1 June 2000. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "2004/926/EC: Council Decision of 22 December 2004 on the putting into effect of parts of the Schengen acquis by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland". Official Journal of the European Union. 395: 70–80. 31 December 2004. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "2002/192/EC: Council Decision of 28 February 2002 concerning Ireland's request to take part in some of the provisions of the Schengen acquis". Official Journal of the European Communities. 64: 20–23. 7 March 2002. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Vol. 698 No. 1: Priority Questions – Deputy Joe McHugh (FG) to minister for justice Ahern re: International Agreements". Parliamentary Debates. Office of the Houses of the Oireachtas. 10 December 2009. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Boin, Arjen; Ekengren, Magnus; Rhinard, Mark (2006). "Protecting the Union: Analysing an Emerging Policy Space". Journal of European Integration. 28 (5): 405–421. doi:10.1080/07036330600979573.

- Kirchner, Emil and Sperling, James (2008) EU Security Governance. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Olsson, Stefan (ed.)(2009) Crisis Management in the European Union: Cooperation in the Face of Emergencies. Berlin: Springer.

- Boin, A., Ekengren, M. and Rhinard, M. (2013) The European Union as Crisis Manager: Patterns and Prospects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- "Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Regulation on the European Border and Coastguard" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. European Commission.

- "A European Border and Coast Guard to Protect Europe's External Borders - Press Release". europa.eu. European Commission. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "A European Border and Coast Guard to Protect Europe's External Borders". europa.eu. European Commission. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. European Commission. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. European Commission. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. European Commission. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Regulation on the European Border and Coast Guard" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. European Commission. Retrieved 14 May 2016.