Primacy of European Union law

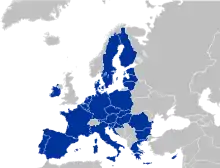

The primacy of European Union law (sometimes referred to as supremacy) is an EU law principle that when there is conflict between European law and the law of its member states, European law prevails, and the norms of national law are set aside. The principle was developed by the European Court of Justice, which interpreted that norms of European law take precedence over any norms of national law, including the constitutions of member states.[1][2][3] Although national courts generally accept the principle in practice, most of them disagree with that absolute principle and reserve, in principle, the right to review the constitutionality of European law under national constitutional law.[4]

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

|

For the European Court of Justice, national courts and public officials must disapply a national norm that is believed not to be compliant with the EU law. Disapplying is different by the European Parliament's legislation in that it concerns to a specific case, and legislation is universal and equivalent for all people. However, disapplication of the national law in a judicial case or administrative procedure can create a legal precedent that is repeated over the time by the same or other courts and so becomes part of the national jurisprudence. The United Kingdom claimed that statement to be contrary to the fundamental principle of the separation of powers into the national jurisdictions since it provides to unelected courts or other nonjurisdictional charges the power to ignore the role of Parliament with a de facto immunity from law enforcement.

Some countries provide that if national and EU law contradict, courts and public officials are required to suspend the application of the national law, ask to the national constitutional court and wait until its decision is taken. If the norm has been declared to be constitutional, they are automatically obliged to apply the national law. That fact can theorically create a contradiction between the national constitutional court and the European Court of Justice. It can also originate from a contradiction between two primary sources in the hierarchy of the sources of law: the constitutions of the individual states and Union law.

Development

In Costa v. ENEL.[5] Mr Costa was an Italian citizen opposed to the nationalisation of energy companies. Because he had shares in a private corporation subsumed by the nationalised company, ENEL, he refused to pay his electricity bill in protest. In the subsequent suit brought to Italian courts by ENEL, he argued that nationalisation infringed EC law on the state distorting the market.[6] The Italian government believed that not to be an issue that even could be complained about by a private individual since it was a decision to make by a national law. The ECJ ruled in favour of the government because the relevant treaty rule on an undistorted market was one on which the Commission alone could challenge the Italian government. As an individual, Mr Costa had no standing to challenge the decision, because that treaty provision had no direct effect.[7] But on the logically prior issue of Mr Costa's ability to raise a point of EC law against a national government in legal proceeding before the courts in that member state the ECJ disagreed with the Italian government. It ruled that EC law would not be effective if Mr Costa could not challenge national law on the basis of its alleged incompatibility with EC law.

It follows from all these observations that the law stemming from the treaty, an independent source of law, could not, because of its special and original nature, be overridden by domestic legal provisions, however framed, without being deprived of its character as community law and without the legal basis of the community itself being called into question.[8]

In other cases, state legislatures write the precedence of EU law into their constitutions. For example, the Constitution of Ireland contains this clause: "No provision of this Constitution invalidates laws enacted, acts done or measures adopted by the State which are necessitated by the obligations of membership of the European Union or of the Communities".

- C-106/77, Simmenthal [1978] ECR 629, duty to set aside provisions of national law that are incompatible with Union law.

- C-106/89 Marleasing [1991] ECR I-7321, national law must be interpreted and applied, if possible, to avoid a conflict with a Community rule.

Article I-6 of the European Constitution stated: "The Constitution and law adopted by the institutions of the Union in exercising competences conferred on it shall have primacy over the law of the Member States". Although constitution was never ratified, its replacement, the Treaty of Lisbon, included the following declaration on primacy:

17. Declaration concerning primacy

The Conference recalls that, in accordance with well settled case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union, the Treaties and the law adopted by the Union on the basis of the Treaties have primacy over the law of Member States, under the conditions laid down by the said case law.

The Conference has also decided to attach as an Annex to this Final Act the Opinion of the Council Legal Service on the primacy of EC law as set out in 11197/07 (JUR 260):Opinion of the Council Legal Service

of 22 June 2007

It results from the case-law of the Court of Justice that primacy of EU law is a cornerstone principle of Union law. According to the Court, this principle is inherent to the specific nature of the European Community. At the time of the first judgment of this established case law (Costa/ENEL,15 July 1964, Case 6/641 (1) there was no mention of primacy in the treaty. It is still the case today. The fact that the principle of primacy will not be included in the future treaty shall not in any way change the existence of the principle and the existing case-law of the Court of Justice.

(1) It follows (...) that the law stemming from the treaty, an independent source of law, could not, because of its special and original nature, be overridden by domestic legal provisions, however framed, without being deprived of its character as Community law and without the legal basis of the Community itself being called into question.

Particular countries

Depending on the constitutional tradition of member states, different solutions have been developed to adapt questions of incompatibility between State law and Union law to one another. EU law is accepted as having supremacy over the law of member states, but not all member states share the ECJ's analysis on why EU law takes precedence over state law if there is a conflict.

Belgium

In its ruling of 27 May 1971, often nicknamed the "Franco-Suisse Le Ski ruling" or "Cheese Spread ruling" (Dutch: Smeerkaasarrest), the Belgian Court of Cassation ruled that self-executing treaties prevail over national law, and even over the Belgian Constitution.[10]

As a consequence, EU regulations prevail over Belgian national law. EU directives do not prevail unless they are converted to national law.

Czech Republic

Article 10 of the Constitution of the Czech Republic states that every international treaty ratified by the Parliament of the Czech Republic is part of the Czech legislative order and takes precedence over all other laws.[11]

France

Like many other countries within the civil law legal tradition, France's judicial system is divided between ordinary and administrative courts. The ordinary courts accepted the supremacy of EU law in 1975, but the administrative courts accepted the doctrine only in 1990. The supreme administrative court, the Conseil d'Etat, had held that as the administrative courts had no power of judicial review over legislation enacted by the French Parliament, they could not find that national legislation was incompatible with Union law or give it precedence over a conflicting State law. That was in contrast to the supreme ordinary court, the Cour de cassation; in the case of Administration des Douanes v Société 'Cafes Jacques Vabre' et SARL Wiegel et Cie,[12] it ruled that precedence should be given to Union law over State law in line with the requirements of the Article 55 of the French Constitution, which accorded supremacy to ratified international treaty over State law. The administrative courts finally changed their position in the case of Raoul Georges Nicolo[13] by deciding to follow the reasoning used by the Cour de cassation. However, both ordinary courts and administrative courts still reject the primacy of EU law over the French constitution.

Germany

In Solange II,[14] the German Constitutional Court held that so long as (German: solange) EU law had a level of protection of fundamental rights that is substantially in concurrence with the protections afforded by the German constitution, it would no longer review specific EU acts in light of that constitution.

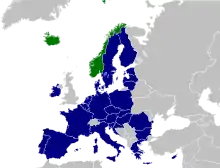

Ireland

The Third Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland explicitly provided for the supremacy of EU law in the Republic of Ireland by providing that no other provision of the Irish constitution could invalidate laws enacted if they were necessitated by membership of the European Communities. In Crotty v. An Taoiseach, the Irish Supreme Court held that the ratification of the Single European Act by the Republic of Ireland was not necessitated by membership of the European Communities and so could be subject to review by the courts.

Italy

In Frontini v. Ministero delle Finanze,[15] the plaintiff sought to have a national law disregarded without having to wait for the Italian Constitutional Court do so. The ECJ ruled that every State's supreme court must apply Union law in its entirety.

Lithuania

The Lithuanian Constitutional Court concluded on 14 March 2006 in case no. 17/02-24/02-06/03-22/04, § 9.4 in Chapter III, that EU law has supremacy over ordinary legal acts of the Lithuanian Parliament but not over the Lithuanian constitution. If the Constitutional Court finds EU law to be contrary to the constitution, the former law loses its direct effect and shall remain inapplicable.[16]

Malta

Article 65 of the Maltese constitution provides that all laws made by Parliament must be consistent with EU law and Malta's obligations deriving from its Treaty of Accession.[17]

Poland

The Constitutional Tribunal of Poland ruled that while EU law may override member state statutes, it does not override the Polish constitution. In a conflict between EU law and the constitution, Poland can make a sovereign decision as to how this conflict should be resolved (by changing the constitution, leaving the EU or seeking to change the EU law).[18]

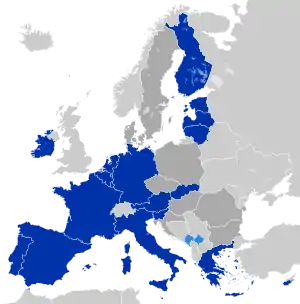

Former members

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom was a member state of the European Union and its predecessor the European Communities from 1 January 1973 until 31 January 2020. During this time the issue of EU law taking precedence over national law was a significant issue and a cause for debate both among politicians and even in the judiciary.

In R v Secretary of State for Transport, ex p Factortame Ltd, the House of Lords ruled that courts in the United Kingdom had the power to "disapply" acts of parliament if they conflicted with EU law. Lord Bridge held that Parliament had voluntarily accepted this limitation of its sovereignty and was fully aware that even if the limitation of sovereignty was not inherent in the Treaty of Rome, it had been well established by jurisprudence before Parliament passed the European Communities Act 1972.[19]

If the supremacy within the European Community of Community Law over the national law of member states was not always inherent in the EEC Treaty it was certainly well established in the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice long before the United Kingdom joined the Community. Thus, whatever limitation of its sovereignty Parliament accepted when it enacted the European Communities Act 1972 was entirely voluntary. Under the terms of the 1972 Act it has always been clear that it was the duty of a United Kingdom court, when delivering final judgment, to override any rule of national law found to be in conflict with any directly enforceable rule of Community law.

In 2011 the UK Government, as part of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement following the 2010 UK general election, passed the European Union Act 2011 in a attempt to address the issue by inserting a sovereignty clause.[20] The clause was enacted in section 18 which says:

Directly applicable or directly effective EU law (that is, the rights, powers, liabilities, obligations, restrictions, remedies and procedures referred to in section 2(1) of the European Communities Act 1972) falls to be recognised and available in law in the United Kingdom only by virtue of that Act or where it is required to be recognised and available in law by virtue of any other Act.

However, in the 2014 case of R (HS2 Action Alliance Ltd) v Secretary of State for Transport, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom said:[21][22]

The United Kingdom has no written constitution, but we have a number of constitutional instruments. They include Magna Carta, the Petition of Right 1628, the Bill of Rights and (in Scotland) the Claim of Rights Act 1689, the Act of Settlement 1701 and the Act of Union 1707. The European Communities Act 1972, the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 may now be added to this list. The common law itself also recognises certain principles as fundamental to the rule of law. It is, putting the point at its lowest, certainly arguable (and it is for United Kingdom law and courts to determine) that there may be fundamental principles, whether contained in other constitutional instruments or recognised at common law, of which Parliament when it enacted the European Communities Act 1972 did not either contemplate or authorise the abrogation.

At 23:00 GMT (00:00 CET in Brussels) on 31 January 2020, the United Kingdom became the first member state to formally leave the European Union after 47 years of membership under the terms of the Brexit withdrawal agreement. At the same time, the European Communities Act 1972 (ECA 1972), the piece of legislation that incorporated EU law (Community law as it was in 1972) into the domestic law of the United Kingdom, was repealed by the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, although the effect of the 1972 Act was saved by the provisions of the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 to enable EU law to continue to have legal effect within the UK until the end of the implementation period, which ended on the 31 December 2020. Since the implementation period has now ended, EU law no longer applies to the UK. However the principle of the supremacy of EU law applies to the interpretation of retained EU law.[23]

See also

- Thoburn v Sunderland City Council (2002)

- Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen (1963)

- Supremacy Clause in United States law

Notes

- Avbelj, Matej (2011). "Supremacy or Primacy of EU Law—(Why) Does it Matter?". European Law Journal. 17 (6): 744. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2011.00560.x.

- Lindeboom, Justin (2018). "Why EU Law Claims Supremacy" (PDF). Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. 38 (2): 328. doi:10.1093/ojls/gqy008.

- Claes, Monica (2015). "The Primacy of EU Law in European and National Law". The Oxford Handbook of European Union Law. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199672646.013.8. ISBN 9780199672646.

- Craig, Paul; De Burca, Grainne (2015). EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 266ff. ISBN 978-0-19-871492-7.

- Case 6/64, Flaminio Costa v. ENEL [1964] ECR 585, 593

- now found in Art. 86 and Art. 87

- "But this obligation does not give individuals the right to allege, within the framework of community law... either failure by the state concerned to fulfil any of its obligations or breach of duty on the part of the commission."

- Case 6/64, Flaminio Costa v. ENEL [1964] ECR 585, 593

- "Declarations annexed to the Final Act of the Intergovernmental Conference which adopted the Treaty of Lisbon". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- Peeters, Patrick; Mosselmans, Jens (2017). "The Constitutional Court of Belgium: Safeguard of the Autonomy of the Communities and Regions". In Aroney, Nicholas; Kincaid, John (eds.). Courts in Federal Countries: Federalists or Unitarists?. Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto Press. p. 89. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt1whm97c.7.

- "Ústava České republiky". www.psp.cz.

- [1975] 2 CMLR 336.

- [1990] 1 CMLR 173.

- Re Wuensche Handelsgesellschaft, BVerfG decision of 22 October 1986 [1987] 3 CMLR 225,265).

- [1974] 2 CMLR 372.

- "Ruling of the Lithuanian Constitutional Court dated 14 March 2006 in case no. 17/02-24/02-06/03-22/04". Lietuvos Respublikos Konstitucinis Teismas.

- Constitution of Malta

- "Verdict of the Constitutional Tribunal of Poland of May 11th, 2005"; K 18/04 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Lord Bridge, 1991, Appeal Cases 603, 658; quoted in Craig, Paul; de Búrca, Gráinne (2007). EU Law, Text, Cases and Materials (4 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 367–368. ISBN 978-0-19-927389-8.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office, "EU Bill to include Parliamentary sovereignty clause" (London, 6 October 2010)

- [2014] UKSC 3 at [207], per Lords Neuberger and Mance

- Group, Constitutional Law (23 January 2014). "Mark Elliott: Reflections on the HS2 case: a hierarchy of domestic constitutional norms and the qualified primacy of EU law".

- "European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 s 5". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 January 2021.