Arts in the Philippines

Arts in the Philippines refer to all the various forms of the arts that have developed and accumulated in the Philippines from the beginning of civilization in the country up to the present era. They reflect the range of artistic influences on the country's culture, including indigenous forms of the arts, and how these influences have honed the country's arts. These arts are divided into two distinct branches, namely, traditional arts[1] and non-traditional arts.[2] Each branch is further divided into various categories with subcategories.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Overview

The National Commission for Culture and the Arts, the official cultural agency of the government of the Philippines, has categorized Filipino arts into traditional and non-traditional. Each category are split into various arts, which in turn have sub-categories of their own.

- (A) Traditional arts[1]

- Folk architecture – including, but not limited to, stilt houses, land houses, and aerial houses

- Maritime transport – boat houses, boat-making, and maritime traditions

- Weaving – including, but not limited to, basket weaving, back-strap loom weaving, headgear weaving, fishnet weaving, and other forms of weaving

- Carving – including, but not limited to, woodcarving and folk non-clay sculpture

- Folk performing arts – including, but not limited to, dances, plays, and dramas

- Folk (oral) literature – including, but not limited to, epics, songs, and myths

- Folk graphic and plastic arts – including, but not limited to, calligraphy, tattooing, folk writing, folk drawing, and folk painting

- Ornament, textile, or fiber art – hat-making, mask-making, accessory-making, ornamental metal crafts

- Pottery – including, but not limited to, ceramic making, clay pot-making, and folk clay sculpture

- Other artistic expressions of traditional culture – including, but not limited to, non-ornamental metal crafts, martial arts, supernatural healing arts, medicinal arts, and constellation traditions

- (B) Non-traditional arts[2]

- Dance – including, but not limited to, dance choreography, dance direction, and dance performance

- Music – including, but not limited to, musical composition, musical direction, and musical performance

- Theater – including, but not limited to, theatrical direction, theatrical performance, theatrical production design, theatrical light and sound design, and theatrical playwriting

- Visual arts – including, but not limited to painting, non-folk sculpture, printmaking, photography, installation art, mixed media works, illustration, graphic arts, performance art, and imaging

- Literature – including, but not limited to, poetry, fiction, essay, and literary/art criticism

- Film and broadcast arts – including, but not limited to, film and broadcast direction, film and broadcast writing, film and broadcast production design, film and broadcast cinematography, film and broadcast editing, film and broadcast animation, film and broadcast performance, and film and broadcast new media

- Architecture and allied arts – including, but not limited to, non-folk architecture, interior design, landscape architecture, and urban design

- Design – including, but not limited to, industrial design, and fashion design

Traditional arts

The traditional arts in the Philippines encompass folk architecture, maritime transport, weaving, carving, folk performing arts, folk (oral) literature, folk graphic and plastic arts, ornament, textile, or fiber art, pottery, and other artistic expressions of traditional culture.[1] There are numerous Filipino specialists or experts on the various fields of traditional arts, with those garnering the highest distinctions declared as Gawad Manlilikha ng Bayan (GAMABA), equal to National Artist.

Folk architecture

Folk architecture in the Philippines differ significantly per ethnic group, where the structures can be made of bamboo, wood, rock, coral, rattan, grass, and other materials. These abodes can range from the hut-style bahay kubo which utilizes vernacular mediums in construction, the highland houses called bale that may have four to eight sides, depending on the ethnic association, the coral houses of Batanes which protects the natives from the harsh sandy winds of the area, the royal house torogan which is engraved with intricately-made okir motif, and the palaces of major kingdoms such as the Daru Jambangan or Palace of Flowers, which was the seat of power and residence of the head of Sulu prior to colonization. Folk architecture also includes religious buildings, generally called as spirit houses, which are shrines for the protective spirits or gods.[3][4][5] Most are house-like buildings made of native materials, and are usually open-air.[6][3] Some were originally pagoda-like, a style later continued by natives converted into Islam, but have now become extremely rare.[7] There are also buildings that have connected indigenous and Hispanic motif, forming the bahay na bato architecture, and its proto-types. Many of these bahay na bato buildings have been declared as world heritage site, as part of Vigan.[8] Folk structures include simple sacred stick stands to indigenous castles or fortresses such as the idjang, to geologically-altering works of art such as the Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras, locally called payyo.[9][10][11] Five rice terrace clusters have been declared as world heritage sites, namely Nagacadan, Hungduan, central Mayoyao, Bangaan, and Batad.[12]

Rice granaries from Ifugao, called bale

Rice granaries from Ifugao, called bale Bahay kubo-style Mabini House

Bahay kubo-style Mabini House Daru Jambangan (Palace of Flowers), the royal residence of the ruler of the Tausug

Daru Jambangan (Palace of Flowers), the royal residence of the ruler of the Tausug Scaled-down replica of the torogan, inspired by the Kawayan Torogan, a National Cultural Treasure in Lanao del Sur

Scaled-down replica of the torogan, inspired by the Kawayan Torogan, a National Cultural Treasure in Lanao del Sur

A simple bahay kubo house

A simple bahay kubo house Some bahay na bato houses

Some bahay na bato houses_11.JPG.webp) Casa Residencia in Dapitan

Casa Residencia in Dapitan Dakay house, the oldest surviving coral houses in the Philippines still used today (c. 1887)

Dakay house, the oldest surviving coral houses in the Philippines still used today (c. 1887) Bahay kubo-style Felipe Agoncillo house

Bahay kubo-style Felipe Agoncillo house Bahay kubo-style Quezon Birth House

Bahay kubo-style Quezon Birth House Bahay kubo-style Macapagal Library and Museum

Bahay kubo-style Macapagal Library and Museum Bahay kubo-style house in Camiguin

Bahay kubo-style house in Camiguin_-_Flickr.jpg.webp) Traditional houses in Lagawe, Ifugao

Traditional houses in Lagawe, Ifugao A simple bahay kubo-style house in Palawan

A simple bahay kubo-style house in Palawan

Coral houses in Sabtang

Coral houses in Sabtang Bahay na bato-style Yap-Sandiego House

Bahay na bato-style Yap-Sandiego House Bahay na bato-style Juban Sorsogon House

Bahay na bato-style Juban Sorsogon House Casa Redonda, one of the main structures at José Rizal Memorial Protected Landscape in Dapitan

Casa Redonda, one of the main structures at José Rizal Memorial Protected Landscape in Dapitan

Batad Rice Terraces

Batad Rice Terraces

Batad Rice Terraces in the Philippines

Batad Rice Terraces in the Philippines.jpg.webp) Hapao Rice Terraces

Hapao Rice Terraces

Vega Ancestral House, built with the bahay na bato prototype style with sculptures of Atlases

Vega Ancestral House, built with the bahay na bato prototype style with sculptures of Atlases.jpg.webp) Tutuban Center Main Building

Tutuban Center Main Building Bahay na bato-style Lazi convent

Bahay na bato-style Lazi convent Bahay na bato in Intramuros

Bahay na bato in Intramuros Bahay na bato-style Museo de Loboc

Bahay na bato-style Museo de Loboc Casa Manila

Casa Manila Bahay na bato-style Hizon-Ocampo House

Bahay na bato-style Hizon-Ocampo House Bahay na bato-style Henson-Hizon House

Bahay na bato-style Henson-Hizon House Bahay na bato-style Balay Negrense

Bahay na bato-style Balay Negrense Coral house in Batanes

Coral house in Batanes Bahay na bato-style Archdiocesan Chancery

Bahay na bato-style Archdiocesan Chancery Bahay na bato-style Jose Laurel House

Bahay na bato-style Jose Laurel House Bahay na bato-style Bahay na Pula

Bahay na bato-style Bahay na Pula Bahay na bato-style houses inside Intramuros

Bahay na bato-style houses inside Intramuros

Maritime transport

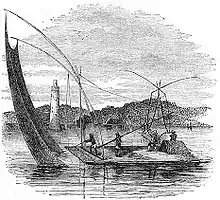

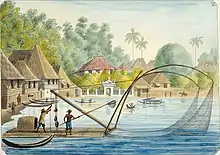

Maritime transport in the Philippines includes boat houses, boat-making, and maritime traditions. These structures, traditionally made of wood chosen by elders and craftsfolks, were used as the main vehicles of the people, connecting one island to another, where the seas and rivers became the people's roads. Although boats are believed to have been used in the archipelago for thousands of years since the arrival of humans through water, the earliest evidence of boat-making and the usage of boats in the country continues to be dated as 320 AD through the carbon-dating of the Butuan boats that are identified as remains of a gigantic balangay.[13]

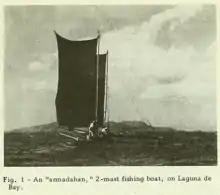

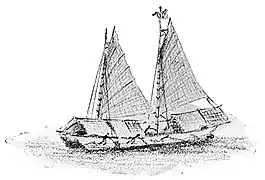

Aside from the balangay, there are various styles and types of indigenous sea vehicles throughout the Philippines, such as the two-masted double-outrigger boat armadahan,[14][15] the trading ship avang,[16] the dugout canoes awang,[17] the large sailing outrigger ship balación,[18] the native and widely-available watercraft bangka,[19] the tiny canoe bangka anak-anak,[20] the salambáw-lifting basnigan,[21] the small double-outrigger sailboat bigiw,[22] the dugout canoe birau,[20] the dugout canoe buggoh,[20] the flat-floored and roofed casco,[23] the single mast and pointed chinarem,[16] the rough sea open-deck boat Chinedkeran,[16] the large double-outrigger plank boat djenging,[20] the pirate warship garay,[24] the large sailing outrigger ship guilalo,[25] the open deck boat falua,[16] the canoe junkun,[20] the small motorized boat junkung,[26] the large outrigger warship karakoa,[27] the large outrigger warship lanong,[28] the houseboat lepa,[29] the raft ontang,[20] the lake canoe owong,[30] the open-deck fishing boat panineman,[16] the double outrigger sailboat paraw,[31] the war canoe salisipan,[32] the small fishing boat tataya,[16] the motorized boat tempel, the dinghy tiririt,[33] and the outrigger boat vinta, among many others.[34] From 1565 to 1815, ships called the Manila galleons were also built by Filipino artisans.[35]

.jpg.webp) A large karakoa outrigger warship, 1711

A large karakoa outrigger warship, 1711 A balangay reconstruction

A balangay reconstruction.jpg.webp) The Sama-Bajau's lepa house-boat with elaborate carvings

The Sama-Bajau's lepa house-boat with elaborate carvings

.jpg.webp) A large lanong outrigger warship, 1890

A large lanong outrigger warship, 1890.jpg.webp) Filipino boat-builders in a Cavite shipyard (1899)

Filipino boat-builders in a Cavite shipyard (1899)

.png.webp) Garay warships of the Banguingui

Garay warships of the Banguingui

An armadahan at Laguna de Bay (1968)

An armadahan at Laguna de Bay (1968).jpg.webp) War canoe salisipan, 1890

War canoe salisipan, 1890.png.webp) Painting of a balación, 1847

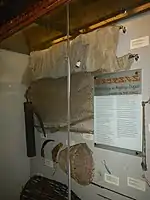

Painting of a balación, 1847 Some of the remains of the Butuan Balangay (320 AD), a National Cultural Treasure

Some of the remains of the Butuan Balangay (320 AD), a National Cultural Treasure A Manila galleon visiting Micronesia, c. 1590s

A Manila galleon visiting Micronesia, c. 1590s A casco, 1906

A casco, 1906

Weaving

Weaving is an ancient art form that continue in the Philippines today, with each ethnic group having their distinct weaving techniques.[36] The weaving arts are composed of basket weaving, back-strap loom weaving, headgear weaving, fishnet weaving, and other forms of weaving.

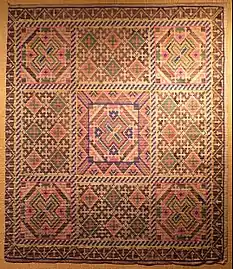

Cloth and mat weaving

Expensive textiles are made through the intricate and difficult process called back-strap looming.[37] Fibers such as Cotton, abaca, banana fiber, grass, and palm fiber are used in the Filipino weaving arts. There are many types of weaved cloths in the Philippines. Pinilian is an Ilocano cotton cloth weaved using a pangablan, where weaving styles of binakul, binetwagan, or tinumballitan are inputted. Bontoc weave revolves on the concept of centeredness, a key cultural motif among the Bontoc people. In its weave, the process starts with the sides called langkit until it journeys into the pa-ikid (side panels), fatawil (warp bands), and shukyong (arrows). Afterwards, the sinamaki weaving commences, where the tinagtakho (human figure), minatmata (diamond), and tinitiko (zigzag) are incorporated. The last is center, pa-khawa, which features the kan-ay (supplementary weft). Kalinga textiles are embedded into the geometry, where motifs include continuous lozenge pattern locally called inata-ata, and mother-of-pearl platelets called pawekan, among many others. The piña fabric is considered the finest indigenous Filipino-origin textile. Those made by the Aklanon are the most prized, and are utilized in the national costumes of the country, such as barong Tagalog. Hablon is the fine textiles of the Karay-a and Hiligaynon people, which have been known from the epics of the people. The textile is usually used for Visayan patadyong and panuelo. The saputangan tapestry weave of the Yakan people is a highly skilled weaving utilizing the bunga-sama supplementary weft weave, the siniluan warp-floating pattern, the inalaman supplementary-weft technique, and the pinantupan weft band pattern. Mabal tabih of the Blaan people depicts crocodiles and curls. Weavers of the art can only be women, as the art is dedicated and taught by Furalo, goddess of weaving. Bagobo inabal utilizes abaca into creating two tube skirts, namely sinukla and bandira. Dagmay is the weaving art of the Mandaya, who use the mud-dye technique in their craft. Meranaw textile is used for the creation of the malong, among many other Maranao clothing. These crafts are imbibed with okir designs including potiok (bud), dapal or raon (leaf), pako (fern), pako rabong (growing fern) and katorai (flower). The pis syabit weave of the Tausug utilizes the free imagination of the weaver, as having no preset pattern for the weave is the cultural standard for making the high art. T'nalak is a fine textile of the Tboli crafted by the dream-weavers who are provided the designs and patterns through dreams by Fu Dalu, the deity of the abaca used in weaving.[39] The oldest known warp ikat textile in Southeast Asia is the Banton cloth of Banton, Romblon, dated at 13th to 14th century.[40]

Unlike cloth weaving, mat weaving does not utilize a loom or similar equipment and instead relies on the craftsfolk's attention in hand-weaving. The difficult art form is known throughout the Philippines, with those made in Sulu, Basilan, and Samar being the most prized. In general traditions throughout the Philippines, mat-weaving is only done in shaded and cool placed as to preserve the integrity of the mats and their fibers. An example is the banig of Basey, where the weavers usually work inside a cave. Fibers used vary from banana, grass, palm, and many others.[41]

Binakol

Binakol Itneg shaman blanket

Itneg shaman blanket

A double ikat mat from Sulu

A double ikat mat from Sulu_from_Mindanao%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art_14180.1.JPG.webp) Rayon Malong

Rayon Malong%252C_Tausug_people%252C_Philippines%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art_14451.1.JPG.webp) Silk Pis siyabit

Silk Pis siyabit_from_the_Philippines%252C_Sulu_Archipelago%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art_.jpg.webp) Silk Patadyong

Silk Patadyong Banton cloth, the oldest surviving ikat textile in Southeast Asia (13th-14th century), a National Cultural Treasure

Banton cloth, the oldest surviving ikat textile in Southeast Asia (13th-14th century), a National Cultural Treasure Filipino shirt made of piña (1850's)

Filipino shirt made of piña (1850's) Mat from Leyte

Mat from Leyte%252C_19th_century_(CH_18386747).jpg.webp)

%252C_early_19th_century_(CH_18386599).jpg.webp) Panel made of silk, piña, and metallic threads (1800's)

Panel made of silk, piña, and metallic threads (1800's)%252C_ca._1770_(CH_18606679).jpg.webp) Silk and piña scarf (1770)

Silk and piña scarf (1770)%252C_19th_century_(CH_18556915).jpg.webp) Cotton and piña textile (1800's)

Cotton and piña textile (1800's)%252C_19th_century_(CH_18386669).jpg.webp) Textile made of pure piña (1800's)

Textile made of pure piña (1800's) Yardage for binakol

Yardage for binakol Kalinga testile used in skirt

Kalinga testile used in skirt Northern Luzon textile used in skirt

Northern Luzon textile used in skirt%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art_7908.1.JPG.webp) Bagobo textile used in skirt

Bagobo textile used in skirt Binakol

Binakol.jpg.webp) Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery

Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery.jpg.webp) Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery

Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery.jpg.webp) Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery

Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery.jpg.webp) Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery

Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery.jpg.webp) Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery

Filipino clothing exhibited at the Philippine Textiles Gallery Terno (1920's)

Terno (1920's) Skirt

Skirt.jpg.webp) Various Filipino textiles at the National Museum

Various Filipino textiles at the National Museum Sash

Sash Mestiza dress (1930's)

Mestiza dress (1930's)

Basketry

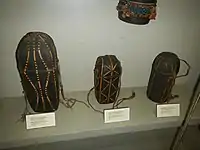

The fine art of basket weaving in the Philippines has developed intricate designs and forms directed for specific purposes such as harvesting, rice storage, travel package, sword case, and so on. The art is believed to have arrived in the archipelago due to human migration, where those at the north were the first to learn the art form. The finest vessel basket crafts made, however, comes from the ethnic groups of Palawan, in the southwest. The Batak of Palawan has utilized the craft into high art, as well as retaining their craft's status as functional art. Intricate basketry can also be found among the Mamanwa, various Negrito groups, Mangyans, Ivatan, and many others. Materials used in basketry differ per ethnic group. Some important materials include bamboo, rattan, pandan, cotton cloth tassel, nito, beeswax, abaca, buri, bark, and dyes. In the same manner, each ethnic group has their own basketry patterns, which include closed-crossed over under weave, closed bamboo double twill weave, spaced rattan pentagon pattern, and closed tetrahedron buri, among many others. A few of the many basketry products from the Philippines include the tupil (lunch box), bukug (basket), kabil (carrying basket), uppig (lunch basket), tagga-i (rice basket), bay'ung (basket-pouch), lig-o (winnowing tray), and binga (bag).[42][43] The weaving traditions of basketry have also been influenced by modern demands.[44]

Weaved headpieces are prevalent throughout the Philippines, wherein multiple cultures utilize a variety of fibers to connect mediums forming Filipino headgears such as the Ivatan's vakul, the head-cloth of the Manobo, and the snake headpiece of the Bontoc.[45] The weaving traditions pertaining to fish traps and gears in the Philippines are expansive, of which the Ilocano people, possibly, possess the vastest array of fish gears among the archipelago's ethnic groups. Notable weaved fish traps include bubo, barekbek, and pamurakan.[46] Another weaving tradition is broom weaving, wherein the most stylized in the Philippines is possibly the talagadaw brooms made under the saked process of the Kalinga people.[47] Other weaved crafts include reed raincoats, slippers, and items used for harvesting, planting, hunting, fishing, house chores, traveling, and foraging.

.jpg.webp) Various rice baskets

Various rice baskets.jpg.webp) Rice transportation baskets

Rice transportation baskets.jpg.webp) Various fish gears

Various fish gears Filipino tobacco basket

Filipino tobacco basket Pasiking or basket bags

Pasiking or basket bags Ivatan woman wearing a vakul

Ivatan woman wearing a vakul T'boli women utilizing the s'laong kinibang in dance

T'boli women utilizing the s'laong kinibang in dance Weaved hornbill headgear of the Ilongot

Weaved hornbill headgear of the Ilongot Gaddang people’s weaved headgear

Gaddang people’s weaved headgear Bachelor's hat made of plants, teeth, tusks, shells, and beats

Bachelor's hat made of plants, teeth, tusks, shells, and beats Filipino weaved hats

Filipino weaved hats.jpg.webp) Ilocano merchants wearing the headgear kattukong and raincoat annangá

Ilocano merchants wearing the headgear kattukong and raincoat annangá Ifugao brooms

Ifugao brooms.jpg.webp) Filipino fisherman with fish gears (c.1875)

Filipino fisherman with fish gears (c.1875) Manila fishermen utilizing the sarambaw fishnet (c. 1800's)

Manila fishermen utilizing the sarambaw fishnet (c. 1800's) Bags (upper) and food covers (below) from Tawi-Tawi

Bags (upper) and food covers (below) from Tawi-Tawi An indigenous fish net

An indigenous fish net Weaved crafts

Weaved crafts Fish nets and other fishing gears

Fish nets and other fishing gears Various weaved fish gears

Various weaved fish gears Baskets from Aurora

Baskets from Aurora Filipino cap

Filipino cap Variant of a Bontoc hat

Variant of a Bontoc hat Filipino cap with teeth, tusk, and shell

Filipino cap with teeth, tusk, and shell Basket crafts made by the Iraya Mangyan

Basket crafts made by the Iraya Mangyan

Carving

The art of carving in the Philippines focuses on woodcarving and folk non-clay sculptures.[48][49]

Woodcarving

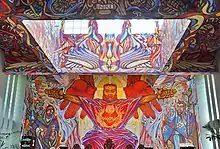

Indigenous woodcarving is one of the most notable traditional arts in the Philippines, with some crafts in various ethnic groups date back prior to Hispanic arrival with perhaps the oldest surviving today are fragments of a wooden boat dating to 320 AD.[50] Many societies utilize a variety of woods into making wood crafts such as sacred bulul figures.[51][52] These divine wooden statues, known in various groups through different generic names, abound throughout the Philippines from the northern Luzon to southern Mindanao.[53] The art of okir on wood is another fine craft attributed to various ethnic groups in Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.[54][55] Wood crafts of specific objects, such as sword hilts, musical instruments, and other objects are also notable, where depictions of ancient mythical beings are usually carved.[56][57] There are other indigenous wood crafts and techniques in the Philippines, some of which have been utilized in Hispanic woodcarvings after colonization, such as the woodcarving styles of Paete.[58][59]

Religious Hispanic woodcarvings abounded in the Philippines with the introduction of Christianity. The techniques utilized infuse both indigenous and Hispanic styles, creating a fusion of Hispanic-Asian wood art. Paete, Laguna is among the most famous woodcarving places in the country, especially on religious Hispanic woodcarving.[58] Various epicenters of woodcarving in the Hispanic tradition are also present in many municipalities, where majority of the crafts are attributed to the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary, where Marian traditions prevail.[60]

Kampilan hilts

Kampilan hilts

_from_Ifugao_in_northern_Luzon%252C_wood_with_seeds%252C_Honolulu.JPG.webp) Standing bulul

Standing bulul Spinning wheel

Spinning wheel.jpg.webp) San Agustin Church door carvings (1607), part of a world heritage site and a National Cultural Treasure

San Agustin Church door carvings (1607), part of a world heritage site and a National Cultural Treasure Christ Child wood statue

Christ Child wood statue Virgin of Sorrow

Virgin of Sorrow Carved saddle panel of the Yakan people, inlaid with shells

Carved saddle panel of the Yakan people, inlaid with shells Carved bas relief at San Agustin Church, Manila

Carved bas relief at San Agustin Church, Manila Ifugao rice spoon guarded by a wooden figure

Ifugao rice spoon guarded by a wooden figure%252C_XV_sec._02.JPG.webp) Bulul god with pamahan cup (15th century)

Bulul god with pamahan cup (15th century) Bulul gods

Bulul gods_from_Ifugao_in_northern_Luzon%252C_wood_with_inlaid_shells%252C_Honolulu.jpg.webp) Bulul gods

Bulul gods%252C_early_20th_century%252C_wood_and_organic_materials%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art.JPG.webp) Shaman box guarded by a wooden figure

Shaman box guarded by a wooden figure.jpg.webp) Various sculptures from Mindanao

Various sculptures from Mindanao Carved sarimanok

Carved sarimanok Wooden chest with bones

Wooden chest with bones Carved miniature winged horse with okir motif

Carved miniature winged horse with okir motif Carved holder for an agong

Carved holder for an agong Maragondon Church door, part of a National Cultural Treasure

Maragondon Church door, part of a National Cultural Treasure Tboli carving of a macaque and a turtle at Lake Sebu's museum

Tboli carving of a macaque and a turtle at Lake Sebu's museum.jpg.webp) Carving depicting a Filipino farmer and a carabao

Carving depicting a Filipino farmer and a carabao Wooden artifacts from northern Luzon

Wooden artifacts from northern Luzon Tomb markers from the Sulu archipelago

Tomb markers from the Sulu archipelago.jpg.webp) Various crafts made with okir

Various crafts made with okir.jpg.webp) Wooden Madonna

Wooden Madonna.jpg.webp) A rare human-like depiction from Bangsamoro

A rare human-like depiction from Bangsamoro.jpg.webp) Carved coconut grinder

Carved coconut grinder.jpg.webp) Giant wooden drums

Giant wooden drums Indigenous chair held by four guardian figures

Indigenous chair held by four guardian figures A number of wooden shields

A number of wooden shields.jpg.webp) Bamboo carving

Bamboo carving Tobacco containers made of wood and bamboo

Tobacco containers made of wood and bamboo Art Deco bas relief at Mirador of the Gala-Rodriguez House

Art Deco bas relief at Mirador of the Gala-Rodriguez House

Stone, ivory, and other carvings

Stone carving is a priced art form in the Philippines, even prior to the arrival of Western colonizers, as seen in the stone likha and larauan or tao-tao crafts of the natives.[61] These items usually represents either an ancestor or a deity who aids the spirit of a loved one to go into the afterlife properly.[62] Ancient carved burial urns have been found in many areas, notably in the Cotabato region.[63] The Limestone tombs of Kamhantik are elaborate tombs in Quezon province, believed to initially possess rock covers signifying that they were sarcophagi. These tombs are believed to have been originally roofed, as evidenced by holes marked onto them, where beams have been placed.[64] Stone grave marks are also notable, with the people of Tawi-Tawi, and other groups using the carved marks with okir motif to aid the dead.[65] In many areas, sides of mountains are carved to form burial caves, especially in the highlands of northern Luzon. The Kabayan Mummy Burial Caves is a prime example.[66] Marble carvings are also famous, especially in its epicenter in Romblon. Majority of the marble crafts are currently meant for export, mostly Buddhist statues and related works.[67] With the arrival of Christianity, Christian stone carvings became widespread. Most of which were either parts of a church such as facades or interior statues, or statues and other crafts intended for personal altars.[68] A notable stone carving on a church is the facade of Miagao Church.[69]

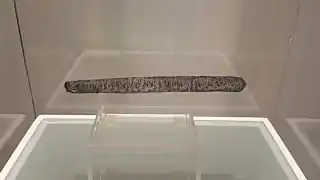

Ivory carving is an art practiced in the Philippines for more than a thousand years, with the oldest known ivory artifact known is the Butuan Ivory Seal, dated 9th–12th century.[70] The religious carvings of ivory, or garing as locally known, became widespread after the direct importation of ivory into the Philippines from mainland Asia, where carvings focused on Christian icons, such as Madonna with Child, the Christ Child, and the Sorrowful Mother.[71] Many of the ivory carvings from the Philippines have gold and silver designs.[71] The ivory trade in the Philippines boomed because of the demand for ivory carvings, and continued up to the 21st century.[72] In recent years, the Philippine government has been cracking down on the illegal ivory trade. In 2013, the Philippines became the first country in the world to destroy its ivory stock, to show solidarity among like-minded nations against the ivory trade which has decimated the world's elephant and rhino populations.[73] Horns of dead carabaos have been used as a substitute to ivory in the Philippines for centuries.[74]

Stone carvings at the facade of Miagao Church, world heritage site and a National Cultural Treasure

Stone carvings at the facade of Miagao Church, world heritage site and a National Cultural Treasure Various ancient carved limestone burial urns

Various ancient carved limestone burial urns Bas relief at Panay Church (1770's)

Bas relief at Panay Church (1770's) Carved vase

Carved vase Carved marbles from Romblon

Carved marbles from Romblon Virgin Mary ivory head with inlaid glass eyes (18-19th century)

Virgin Mary ivory head with inlaid glass eyes (18-19th century) Visayan tenegre buffalo horn hilt

Visayan tenegre buffalo horn hilt Virgin Mary, gilt and painted ivory (17th century)

Virgin Mary, gilt and painted ivory (17th century) Ivory carving of Christ Child with gold paint (1580-1640)

Ivory carving of Christ Child with gold paint (1580-1640) Stamp of the Butuan Ivory Seal (9th-12th century)

Stamp of the Butuan Ivory Seal (9th-12th century) Our Lady of La Naval de Manila, the oldest Christian statue in the Philippines made of ivory (1593 or 1596)

Our Lady of La Naval de Manila, the oldest Christian statue in the Philippines made of ivory (1593 or 1596) An ivory triptych (17th century)

An ivory triptych (17th century)_IMG_9386_Museum_of_Asian_Civilisation.jpg.webp) Mother-of-pearl relief (19th century)

Mother-of-pearl relief (19th century) One of the carvings at the Basilica del Santo Niño

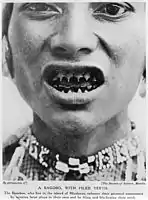

One of the carvings at the Basilica del Santo Niño Teeth filing is present in some ethnic groups in the country

Teeth filing is present in some ethnic groups in the country.jpg.webp) A likha portraying a god, one of only two likha that survived Spanish persecution and destruction

A likha portraying a god, one of only two likha that survived Spanish persecution and destruction.jpg.webp) Limstone burial urn

Limstone burial urn.jpg.webp) Stone artifact with a human head

Stone artifact with a human head.jpg.webp) Limestone burial urn

Limestone burial urn.jpg.webp) An ancient mortar

An ancient mortar Carving at Fort Santa Isabel, Taytay (1748)

Carving at Fort Santa Isabel, Taytay (1748) Detail of carvings at Santo Domingo Church, a National Cultural Treasure

Detail of carvings at Santo Domingo Church, a National Cultural Treasure.jpg.webp) Madonna of the Immaculate Conception, ivory (17th century)

Madonna of the Immaculate Conception, ivory (17th century) Moro helmet, exterior made of carved carabao horn (18th century)

Moro helmet, exterior made of carved carabao horn (18th century) Madonna Santo ivory heads (19th century)

Madonna Santo ivory heads (19th century)

Folk performing arts

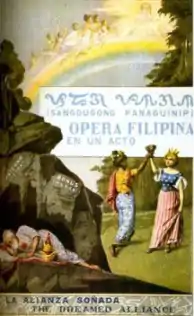

Folk dances, plays, and dramas constitute most of the folk performing arts in the Philippines. Like other Southeast Asian countries, each ethnic group in the Philippines possess their own heritage on folk performing arts, however, Filipino folk performing arts also includes Spanish and American influences due to the country's historical narratives. Some dances are also related to the dances from neighboring Austronesian and other Asian countries.[75] Notable examples of folk performing arts include the banga, manmanok, ragragsakan, tarektek, uyaoy/uyauy,[76] pangalay, asik, singkil, sagayan, kapa malong malong,[77] binaylan, sugod uno, dugso, kinugsik kugsik, siring, pagdiwata, maglalatik, tinikling, subli, cariñosa, kuratsa, and pandanggo sa ilaw.[78][79][80][81] Various folk dramas and plays are known in many epics of the people. Among non-Hispanic traditions, dramas over epics like Hinilawod[82] and Ibalong[83] are known, while among Hispanic groups, the Senakulo is a notable drama.[84][85]

Folk (oral) literature

The arts under folk (oral) literature include the epics, songs, myths, and other oral literature of numerous ethnic groups in the Philippines.

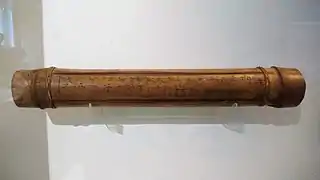

The poetic arts in the Philippines has been attributed as high in form and full of metaphor.[86] Tanaga poetry consists of 7777 syllable count, but rhymes range from dual rhyme forms to freestyle forms.[86] Awit poetry consists of 12-syllable quatrains, following the pattern of rhyming stanzas of established epics such as Pasyon,[87][88] which is chanted through the pabasa.[89] A notable awit epic-poem is the 1838 Florante at Laura.[90] Dalit poetry consists of four lines with eight syllables each.[91] Ambahan poetry consists of seven syllable lines with rhythmic end-syllables, often chanted without a determined musical pitch or musical instrument accompaniment, meant to express in an allegorical way, liberally using poetic language, certain situations or certain characteristics referred to by the one reciting the poem. It cam also be written on bamboo.[92] A notable poetry duel in the Philippines is Balagtasan, which is a debate done in verses.[93] Some notable poems include A la juventud filipina,[94] Ako'y may alaga,[95] and Kay Selya.[96]

Notable epic-poems include 17 cycled and 72,000 lined Darangen of the Maranao[97] and the 29,000-versed Hinilawod of Panay.[98] Other epic-poems from the Philippines include Biag ni Lam-Ang of the Ilocano, Ibalon of the Bicolano, Hudhud and Alim of the Ifugao, Ulalim cycle of the Kalinga, Lumalindaw of the Gaddang, Kudaman of Palawan, Agyu Cycle of the Manobo, Tulelangan of the Ilianon Manobos, Gumao of Dumalinao, Ag Tubig Nog Keboklagan, Keg Sumba Neg Sandayo of the Subanon, and Tudbulul of the Tboli people, among many others. [99] The Filipino Sign Language is used in the country to also pass on oral literature to Filipinos with hearing impairment.[100]

The oral literature have shaped the people's thinking and way of life, providing basis for values, traditions, and societal systems that aid communities in multiple facets of life. As diverse as Filipino folk literature is, many of the literary works continue to develop, with some being documented by scholars and inputted into manuscripts, tapes, video recordings, or other documentary forms.[101][102]

Singkil, a tradition depicting the stories from the Darangen, a world intangible heritage and a National Cultural Treasure

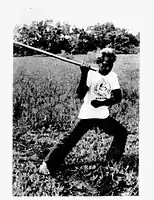

Singkil, a tradition depicting the stories from the Darangen, a world intangible heritage and a National Cultural Treasure An Ifugao chanting the Hudhud ni Aliguyon while harvesting, a world intangible heritage and a National Cultural Treasure

An Ifugao chanting the Hudhud ni Aliguyon while harvesting, a world intangible heritage and a National Cultural Treasure Bakunawa, a deity from the Visayas and Bicol, in a divination-rotation chart as explained in Signosan (1919)

Bakunawa, a deity from the Visayas and Bicol, in a divination-rotation chart as explained in Signosan (1919) A manananggal drawing, as depicted in folk stories

A manananggal drawing, as depicted in folk stories A buraq sculpture, as depicted in folk stories

A buraq sculpture, as depicted in folk stories Sculpture depicting Makiling, the protector-goddess of Mount Makiling

Sculpture depicting Makiling, the protector-goddess of Mount Makiling A hogang, fern-trunk statue, of a god protecting boundaries in Ifugao

A hogang, fern-trunk statue, of a god protecting boundaries in Ifugao Performance at the Kaamulan, depicting gods and heroes from the people's ancient religions

Performance at the Kaamulan, depicting gods and heroes from the people's ancient religions

Folk graphic and plastic arts

The fields under folk graphic and plastic arts are tattooing, folk writing, and folk drawing and painting.

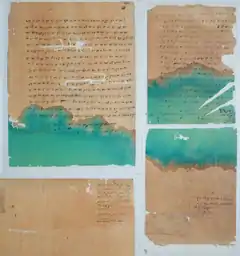

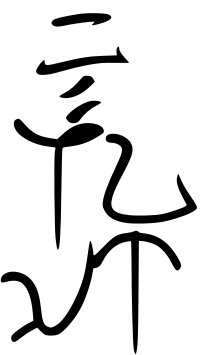

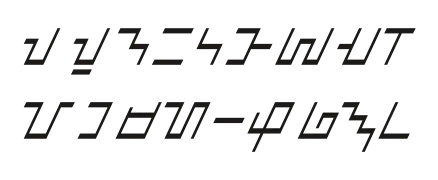

Folk writing (calligraphy)

The Philippines has numerous indigenous scripts collectively called as suyat, each of which has their own forms and styles of calligraphy. Various ethno-linguistic groups in the Philippines prior to Spanish colonization in the 16th century up to the independence era in the 21st century have used the scripts with various mediums. By the end of colonialism, only four of the suyat scripts survived and continue to be used by certain communities in everyday life. These four scripts are hanunó'o/hanunoo of the Hanuno'o Mangyan people, buhid/build of the Buhid Mangyan people, Tagbanwa script of the Tagbanwa people, and palaw'an/pala'wan (ibalnan) of the Palaw'an people. All four scripts were inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme, under the name Philippine Paleographs (Hanunoo, Buid, Tagbanua and Pala’wan), in 1999.[103]

Due to dissent from colonialism, many artists and cultural experts have revived the usage of suyat scripts that went extinct due to Spanish persecution. These scripts being revived include the kulitan script of the Kapampangan people, the badlit script of various Visayan ethnic groups, the iniskaya script of the Eskaya people, the baybayin script of the Tagalog people, the sambali script of the Sambal people, the basahan script of the Bicolano people, the sulat pangasinan script of the Pangasinense people, and the kur-itan or kurdita script of the Ilocano people, among many others.[104][105][106][107][108] Aside from the native suyat calligraphies of the Philippines,[109][110][111] Spanish-derived calligraphy[112] and Arabic calligraphy of jawi and kirim are also used by certain communities and art groups in the Philippines.[113][114] In the last decade, calligraphy based on the suyat scripts has met popularity surges and revival.[115][116] Philippine Braille is the script used by Filipinos with visual impairment.[117]

.jpg.webp)

Amami, a fragment of a prayer written in kur-itan or kurdita, the first to use the krus-kudlit

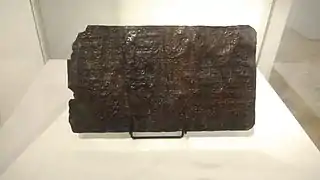

Amami, a fragment of a prayer written in kur-itan or kurdita, the first to use the krus-kudlit Laguna Copperplate Inscription written in the kawi script, precursor to baybayin (900 CE), a National Cultural Treasure

Laguna Copperplate Inscription written in the kawi script, precursor to baybayin (900 CE), a National Cultural Treasure.jpg.webp) Basahan (surat bikol) script sample

Basahan (surat bikol) script sample Hanunó'o calligraphy written on bamboo

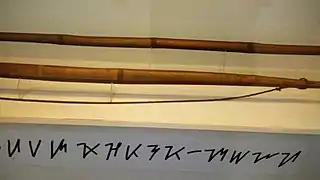

Hanunó'o calligraphy written on bamboo Cursive Latin calligraphy sample (upper part)

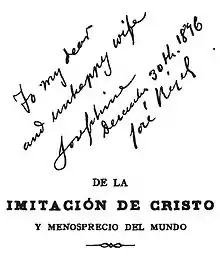

Cursive Latin calligraphy sample (upper part) University of Santo Tomas Baybayin Documents written on paper (c.1613 and 1625), a National Cultural Treasure

University of Santo Tomas Baybayin Documents written on paper (c.1613 and 1625), a National Cultural Treasure Kulitan calligraphy sample

Kulitan calligraphy sample Tagbanwa calligraphy written on a musical instrument (tube zither)

Tagbanwa calligraphy written on a musical instrument (tube zither) Buhid script sample

Buhid script sample An undecipherable script written on the Butuan Silver Paleograph, a National Cultural Treasure

An undecipherable script written on the Butuan Silver Paleograph, a National Cultural Treasure Jawi script, used in the Sulu archipelago

Jawi script, used in the Sulu archipelago The Koran of Bayang, written in the kirim script on paper, a National Cultural Treasure; kirim is used in mainland Muslim Mindanao

The Koran of Bayang, written in the kirim script on paper, a National Cultural Treasure; kirim is used in mainland Muslim Mindanao Eskaya script sample

Eskaya script sample Mosaic mural with baybayin at Baclaran Church

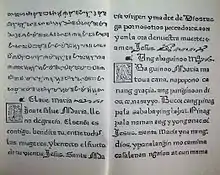

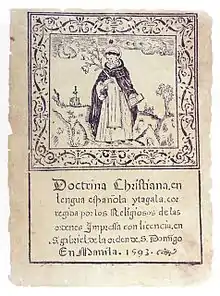

Mosaic mural with baybayin at Baclaran Church Pages of the Doctrina Christiana, an early Christian book in Spanish, Tagalog in Latin script and in Baybayin (1593)

Pages of the Doctrina Christiana, an early Christian book in Spanish, Tagalog in Latin script and in Baybayin (1593) Butuan Ivory Seal, the earliest known ivory craft in the Philippines

Butuan Ivory Seal, the earliest known ivory craft in the Philippines.jpg.webp) One of the Monreal Stones

One of the Monreal Stones_Baybayin.jpg.webp) Indigenous script in the country's passport

Indigenous script in the country's passport Tagbanwa calligraphy on bamboo

Tagbanwa calligraphy on bamboo

Folk drawing and painting

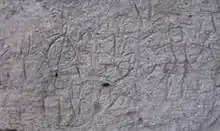

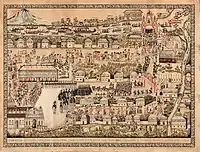

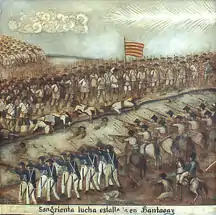

Folk drawings have been known for thousands of years in the archipelago. The oldest folk drawing is the rock drawings and engravings which include the petroglyphs in Angono (Rizal), which was created during the Neolithic age of the Philippines, corresponding to 6000 BC to 2000 BC. The drawings have been interpreted as religious in nature, with infant drawings made to relieve the sickness of children.[118] Another known petroglyph is in Alab (Bontoc), which is dated to be not later than 1500 BC, and represents symbols of fertility such as the pudenda. In contrast, ancient folk drawings as petrographs can be found in specific sites in the country as well. The petrographs of Peñablanca in Cagayan compose charcoal drawings. The petrographs of Singnapan in southern Palawan are also drawn with charcoal. The petrograhs in Anda (Bohol) comppose drawings made with red hematite.[119] Recently discovered petrographs in Monreal (Ticao) include drawings of monkeys, human faces, worms or snakes, plants, dragonflies, and birds.[120]

Folk paintings, like folk drawings, are works of art that usually include depictions of folk culture. Evidences suggest that the people of the archipelago have been painting and glazing their potteries for thousands of years. Pigments used in paintings range from gold, yellow, reddish purple, green, white, blue-green, to blue.[121] Statues and other creations have also been painted on by various ethnic groups, using a variety of colors. Paintings on skin with elaborate designs is also a known folk art which continue to be practiced in the Philippines, especially among the Yakan people.[122]

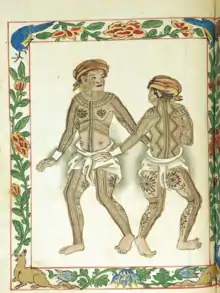

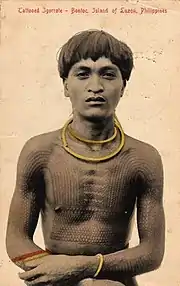

Tattooing was introduced by Austronesian ancestors thousands of years ago, where it developed into cultural symbols in a variety of ethnic groups.[123][124][125] Although the practice has been in place for thousands of years, its documentation was first put on paper in the 16th century, where the bravest Pintados (people of central and eastern Visayas) were the most tattooed. Similar tattooed peoples were documented among the Bicolanos of Camarines and Tagalogs of Marinduque. [126][127][128] Tattooed people in Mindanao include the Manobo, where their tattoo tradition is called pang-o-túb.[129][130] The T'boli also tattoo their skin, believing that the tattoos glow after death, guiding the soul in its journey into the afterlife.[131] But perhaps the most popular tattooed people in the Philippines are the highland peoples of Luzon collectively called the Igorot, where they are traditionally tattooed prior to colonization. Presently, only the small village of Tinglayan in Kalinga province has traditional tattoo artists crafting the batok, headed by master tattooist and Kalinga matriarch Whang-od.[132][133] In the last decade, the many traditional tattoo arts of the Philippines has experienced a revival after centuries of decline.[134] Body folk drawing adornment through scarification also exist among certain ethnic groups in the Philippines.[135]

A portion of the Angono Petroglyphs (6000-2000 BC), a National Cultural Treasure

A portion of the Angono Petroglyphs (6000-2000 BC), a National Cultural Treasure Yakan couple with traditional facial paintings called tanyak tanyak

Yakan couple with traditional facial paintings called tanyak tanyak Painting made with the Waray people’s kut-kut technique, developed in Samar

Painting made with the Waray people’s kut-kut technique, developed in Samar Painted buraq wood sculpture from Muslims of Bangsamoro

Painted buraq wood sculpture from Muslims of Bangsamoro Painted ivory statue of St. Joseph (17th century)

Painted ivory statue of St. Joseph (17th century) Pintados recorded in the Boxer Codex (c. 1590)

Pintados recorded in the Boxer Codex (c. 1590) Whang-od crafting a tattoo (21st century)

Whang-od crafting a tattoo (21st century)_(14761627334).jpg.webp) Some recorded Igorot tattoos (c. 1896)

Some recorded Igorot tattoos (c. 1896) Tattooed Bontoc

Tattooed Bontoc Aeta man with body scarification

Aeta man with body scarification

Ornament, textile, or fiber art

Ornament, textile, or fiber art includes a variety of fields, ranging from hat-making, mask-making, accessory-making, to ornamental metal crafts, and many others.[1]

Glass art

Glass art is an old art form in the Philippines, with many artifacts made of glass found in some sites such as Pinagbayanan.[136] Stained glasses have been in place in many churches in the country since Spanish occupation. Initially, European craftfolks managed the production of stained glasses in the country, but later on, Filipino craftfolks also entered the scene, notably since the 20th century.[137] A important set of stained glass creations is those from the Manila Cathedral, where the pot glass technique was used. The Marian theme is a vivid depiction throughout the glasses, with stern focus on Mary's life and saints in their Marian reverence. Major Our Lady images in the windows include the mother of Peace and Good Voyage, of Expectation, of Consolation, of Loreto, of the Pillar, of Remedies, of “La Naval,” of the Abandoned, of Carmel, of the Miraculous Medal, of the Rule, of Montserrat, of Lourdes, of Peñafrancia, of Perpetual Help, of Fatima, of Sorrows, and of Nasalambao.[138] Some glass arts in the Philippines aside from stained glasses focus on chandeliers and sculptures, among others.[139]

Saint John of the Cross window

Saint John of the Cross window Jeremiah at Aringay church

Jeremiah at Aringay church San Sebastian Church window, part of a National Cultural Treasure

San Sebastian Church window, part of a National Cultural Treasure Marian depictions at the Manila Cathedral

Marian depictions at the Manila Cathedral Zadkiel at Samar church

Zadkiel at Samar church Mary at Mexico church

Mary at Mexico church Parañaque Cathedral window

Parañaque Cathedral window Santo Domingo Church window, part of a National Cultural Treasure

Santo Domingo Church window, part of a National Cultural Treasure San Sebastian Church windows, part of a National Cultural Treasure

San Sebastian Church windows, part of a National Cultural Treasure Cultural Center of the Philippines chandelier

Cultural Center of the Philippines chandelier

Hat-making, mask-making, and related arts

Hat-making is a fine art in many communities throughout the country, with the gourd-based tabungaw of Abra and Ilocos being one of the most prized.[140] Indigenous Filipino hats were widely used in the daily lives of the people until the 20th century when they were replaced by Western-style hats. They are currently worn during certain occasions, such as festivals, rituals, or in theatre.[45][141]

The art of mask creation is both an indigenous and imported tradition, as certain communities have mask-making practices prior to colonization, while some mask-making traditions were introduced through trade from parts of Asia and the West. Today, these masks are worn mostly during festivals, Moriones Festival, and MassKara Festival.[142][143][144] A related art is puppet-making, which is notable for its products used in theater plays and festivals such as the Higantes Festival.[145] Most indigenous masks are made of wood, where these works of art are almost always rudimentary as they represent beings outside basic human comprehension. Gold masks made specifically for the dead also abound in the country, specifically in the Visayas region. However, the practice of gold mask making ceased due to Spanish colonization. Masks made of bamboo and paper used in Lucban depict the proverbial Filipino farming family. Masks of Marinduque are used in pantomimic dramatization, while masks of Bacolod depict egalitarian values, showing ancient traditions of equality among the people, regardless of economic standards. In theater, various masks are notable among epics, especially those related to the Ramayana and Mahabharata.[146]

Gourd-based Salakot (bottom)

Gourd-based Salakot (bottom) Brass helmets (top) from Bangsamoro

Brass helmets (top) from Bangsamoro Bontoc wood hat

Bontoc wood hat Tortoiseshell salakot with inlaid silver

Tortoiseshell salakot with inlaid silver Mandaya people’s sadok

Mandaya people’s sadok Participant with headgear during the Ati-Atihan festival

Participant with headgear during the Ati-Atihan festival Masked participants during the Moriones Festival

Masked participants during the Moriones Festival Elaborate Filipino mask

Elaborate Filipino mask Giant papier-mâché puppets paraded in the Higantes Festival

Giant papier-mâché puppets paraded in the Higantes Festival Masked participants during the MassKara Festival

Masked participants during the MassKara Festival Headgeared children at the Ati-Atihan festival

Headgeared children at the Ati-Atihan festival Masked festival participants

Masked festival participants Various masks used during the Kwaresma

Various masks used during the Kwaresma Masked festival participants

Masked festival participants Performers at the Dinagyang festival

Performers at the Dinagyang festival

Accessory-making

Accessories in the Philippines are almost always worn with their respective combination of garments, with some being used as accessories for houses, altars, and other objects. Among the more than a hundred ethnic groups in the Philippines, the most accessorized is possibly the Kalinga people.[147] The Gaddang people also exhibit a very accessorized culture.[148] The most famous accessories utilized by numerous ethnic groups in the Philippines are omege-shaped fertility objects called a lingling-o, which are used from the northern islands of Batanes to the southern islands of Palawan.[149][150] The oldest lingling-o currently known is dated at 500 BC and is made of nephrite jade.[150] Shells have traditionally been used as fine mediums for accessories in the Philippines as well.[151]

The art of gold craftsmanship is prevalent among Filipino ethnic groups, where the most known goldsmiths came from Butuan. Regalia, jewelries, ceremonial weapons, teeth ornamentation, and ritualistic and funerary objects made of high-quality gold have been excavated in many Filipino sites, attesting the archipelago's flourished gold culture between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. While certain gold craft techniques have been lost due to colonization, later techniques influenced by other cultures have also been adopted by Filipino goldsmiths.[152][153]

Accessory of the Gaddang people

Accessory of the Gaddang people Kankanaey arm band

Kankanaey arm band A lingling-o of the Kalinga people

A lingling-o of the Kalinga people Ilongot earrings

Ilongot earrings Pangalapang

Pangalapang Sipatal pectoral ornament

Sipatal pectoral ornament Ilongot earring

Ilongot earring Filipino gold and coral necklace (17th-18th c.)

Filipino gold and coral necklace (17th-18th c.) Gold necklace (12th-15th century)

Gold necklace (12th-15th century) Gold jewelries (12th-15th century)

Gold jewelries (12th-15th century) Itneg accessory

Itneg accessory Ilongot hair ornament

Ilongot hair ornament Ilongot earrings

Ilongot earrings Kalinga armband

Kalinga armband Bontoc belt

Bontoc belt Mother-of-pearl necklace

Mother-of-pearl necklace Ifugao pectoral accessory

Ifugao pectoral accessory Ilongot pendant

Ilongot pendant Necklaces made of gold, semi-precious stones, and glass (12th-15th century)

Necklaces made of gold, semi-precious stones, and glass (12th-15th century) Kalinga earring

Kalinga earring Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century)

Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century) Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century)

Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century) Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century)

Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century) Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century)

Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century) Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century)

Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century)

Ornamental metal crafts

Ornamental metal crafts are metal-based products that are specifically used to beautify something else, which may or may not be made of metal. They are prized in many communities in the Philippines, where possibly the most sought after are those made by the Maranao, specifically from Tugaya, Lanao del Sur. Metal crafts of the Moro people have been made to decorate a variety of objects, where all are imbibed with the traditional okir motif.[154] Numerous metal crafts are also utilized to design and give emphasis to religious objects such as altars, Christian statues, and clothing, among many other things. Apalit, Pampanga is one of the major centers for the craft.[155] Gold has been utilized in many ornamental crafts of the Philippines, where majority that have survived colonialism and looting are human accessories with elaborate ancient designs.[152]

Our Lady of Manaoag with metal headpiece, part of a National Cultural Treasure

Our Lady of Manaoag with metal headpiece, part of a National Cultural Treasure

Golden garuda ornament from Palawan

Golden garuda ornament from Palawan Nabua Church retablo

Nabua Church retablo Santa Monica Church chandelier, part of a National Cultural Treasure

Santa Monica Church chandelier, part of a National Cultural Treasure Ilongot metal bracelet

Ilongot metal bracelet Indigenous armor from Sulu, made of metal, carabao horn, and silver

Indigenous armor from Sulu, made of metal, carabao horn, and silver Wrought iron at Malolos Church

Wrought iron at Malolos Church Ceiling ornament of Peninsula Hotel's lobby

Ceiling ornament of Peninsula Hotel's lobby Northern Luzon metal belt

Northern Luzon metal belt

Pottery

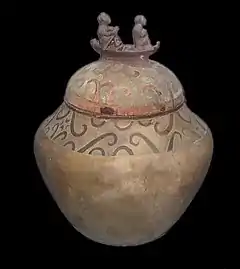

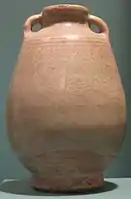

The art of pottery, categorized into ceramic making, clay pot-making, and folk clay sculpture, has long been a part of various cultures in the Philippines, with evidence pointing to a pottery culture dating around 3,500 years ago.[156] Important pottery artifacts from the Philippines include the Manunggul Jar (890-710 BCE)[157] and the Maitum anthropomorphic pottery (5 BC-225 AD).[158] High-fired potteries were first made around 1,000 years ago, which led to what scholars describe as the 'ceramic age' in the Philippines.[121] The ceramic trade also became prevalent, where potteries and shards as far as the Arab world, possibly Egypt, and East Asia has been found in the Philippines according to the National Commission for Culture and the Arts.[121] Specific jars were also traded directly to Japan.[159] Prior to colonization, porcelain imported from foreign lands have already become popular among many communities in the archipelago as seen in the many archaeological porcelains found throughout the islands. While oral literature from Cebu have noted that porcelain were already being produced by the natives during the time of Cebu's early rulers, prior to the arrival of colonizers in the 16th century.[160] Despite this, the earliest known porcelain made by natives of the Philippines is officially dated at 1900s, as porcelain found in Filipino archaeological sites were all branded by the time of their rediscovery as "imported", which has become a major debate today. The late 19th to early 20th century led to Filipinos working as porcelain artisans in Japan to fly back into the Philippines, re-introducing the process of making the craft. All but one porcelain from the era survived World War II.[161] Notable folk clay art in the country include The Triumph of Science over Death (1890),[162] and Mother's Revenge (1894),[163] Popular potteries in the country include tapayan and palayok. The art of pottery has met media attention in recent years, as various techniques and designs are continually being crafted by Filipino artisans.[164][165]

Philippine ceramic (100-1400 CE)

Philippine ceramic (100-1400 CE).jpg.webp) Calatagan Pot with suyat calligraphy (14th-15th century)

Calatagan Pot with suyat calligraphy (14th-15th century).jpg.webp) Burial pots, with the right having wave designs

Burial pots, with the right having wave designs.jpg.webp) The Masuso Pots, portraying breasts in pottery

The Masuso Pots, portraying breasts in pottery.jpg.webp) Pottery from Palawan

Pottery from Palawan Secondary burial jars

Secondary burial jars.jpg.webp) The Intramuros Pot Shard, with a script on it

The Intramuros Pot Shard, with a script on it.jpg.webp) Burial Pots

Burial Pots

Burial jar top of one of the Maitum anthropomorphic pottery from Sarangani (5 BC-370 AD)

Burial jar top of one of the Maitum anthropomorphic pottery from Sarangani (5 BC-370 AD) Striped pottery (500 BC-AD 1000)

Striped pottery (500 BC-AD 1000) Maitum Anthropomorphic Burial Jar No. 13 (5 BC-370 AD), a National Cultural Treasure

Maitum Anthropomorphic Burial Jar No. 13 (5 BC-370 AD), a National Cultural Treasure.jpg.webp) Various ancient burial jars

Various ancient burial jars_among_the_Itneg_people_(1922%252C_Philippines).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) The Mother's Revenge (1894), a National Cultural Treasure

The Mother's Revenge (1894), a National Cultural Treasure Multi-earth-tone burial jar

Multi-earth-tone burial jar.jpg.webp) Multiple clay heads used as toppings for burial jars, each with a unique face

Multiple clay heads used as toppings for burial jars, each with a unique face The Rebulto Jars, portraying a yawning mouth and head

The Rebulto Jars, portraying a yawning mouth and head.jpg.webp) Section of a jar, portraying the human torso

Section of a jar, portraying the human torso.jpg.webp) An ancient mini-jar and a goblet

An ancient mini-jar and a goblet.jpg.webp) An ancient burial jar head

An ancient burial jar head.jpg.webp) An ancient burial jar head

An ancient burial jar head Porcelain found in the Philippines

Porcelain found in the Philippines.jpg.webp) An ancient burial jar head

An ancient burial jar head.jpg.webp) An ancient burial jar head

An ancient burial jar head.jpg.webp) Porcelain found in Palawan (late 12th century)

Porcelain found in Palawan (late 12th century) Porcelain jar found in the Philippines (11th century)

Porcelain jar found in the Philippines (11th century).jpg.webp) Porcelain found in Palawan (15th century)

Porcelain found in Palawan (15th century) Porcelain bowl (15th century)

Porcelain bowl (15th century).jpg.webp) Porcelain found in the Philippines (11th-12th century)

Porcelain found in the Philippines (11th-12th century)

Other artistic expressions of traditional culture

Various traditional arts are too distinct to be categorized into specific sections. Among these art forms include non-ornamental metal crafts, martial arts, supernatural healing arts, medicinal arts, and constellation traditions, among many others.

Non-ornamental metal crafts

Non-ornamental metal crafts are metal products that stand on their own. These crafts are usually already beautiful as they are, and seldom need ornamental metal crafts to further their indigenous aesthetics. Each ethnic group has their own terms for artisans specializing in metal works, with the Moro people being one of the foremost creators of quality metal works, which usually are decorated with the okir motif.[166] Metal crafts are also notable among the craftsfolk of various craft epicenters of the country, such as Baguio in the north.[167] Hispanic metal crafts are prevalent among lowlanders. These crafts usually include giant bells, where the largest in Asia is conserved at Panay Church.[168] Deity crafts made of metals, notably gold, has been found in the Philippines as well, with the Agusan image being a notable example.[152][169]

%252C_Mindanao%252C_Maranao%252C_brass_with_silver_inlay%252C_Honolulu_Academy_of_Arts.JPG.webp) Brass gadur

Brass gadur_from_the_Sulu_Archipelago%252C_brass%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp) Lantaka guns

Lantaka guns Copper betel nut box with silver inlay

Copper betel nut box with silver inlay Ewer from Mindanao (1800)

Ewer from Mindanao (1800)%252C_19th_century_(CH_18466507-2).jpg.webp) Inkwell Stand (19th century)

Inkwell Stand (19th century).jpg.webp) Various metal crafts from Mindanao

Various metal crafts from Mindanao Metal crafts, including liquid vessels

Metal crafts, including liquid vessels.jpg.webp) Metal bell

Metal bell.jpg.webp) Detail of a lantaka gun

Detail of a lantaka gun.jpg.webp) Silver ciborium

Silver ciborium The largest church bell in Asia, housed at Panay Church, a National Cultural Treasure

The largest church bell in Asia, housed at Panay Church, a National Cultural Treasure Manobo jewel case

Manobo jewel case%252C_possibly_19th_century_(CH_18468101-2).jpg.webp) Bronze jars (19th century)

Bronze jars (19th century) Hinged brass box (1800)

Hinged brass box (1800) Bataan monument bell

Bataan monument bell Gangsa gongs of the Kalinga people

Gangsa gongs of the Kalinga people Kulintang gongs of the Maranao people

Kulintang gongs of the Maranao people Metal sculpture in a Pangasinan church

Metal sculpture in a Pangasinan church Karatung gongs of the Teduray people

Karatung gongs of the Teduray people Jar (1800's)

Jar (1800's)

Blade arts

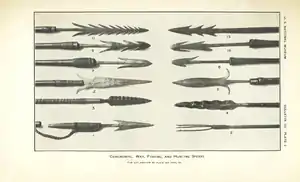

The art of sword making is an ancient tradition in the Philippines, where Filipino bladesmiths have been creating quality swords and other bladed weapons for centuries, with a diverse array of types influenced by the sheer diversity of ethnic groups in the archipelago. Many of the swords are specifically made for ceremonial functions and agricultural functions, while certain types are used specifically for offensive and defensive warfare. The most known Filipino sword is the kampilan, a well-defined sharp blade with an aesthetically-protruding spikelet along the flat side of the tip and a pommel which depicts one of four sacred creatures, a bakunawa (dragon), a buaya (crocodile), a kalaw (hornbill), or a kakatua (cockatoo).[170] Other Filipino bladed weapons include the winged dagger balarao, the convex sword balasiong, the butterfly knife balisong, the modernized sword balisword, the slash-hack sword bangkung, the top-concave sword banyal, the leaf sword barong, the wide-tipped batangas, the machete bolo, the rice-leaf sword dahong palay, the dagger-kalis gunong, the double-edged anti-slip gayang, the machete golok, the wavy sword kalis, the claw knife karambit, the battle axe panabas, the white sword pinutí, the machete pirah, the last-resort knife gunong, the devastation sword susuwat, the sawtooth sword tagan, and the wide-tipped utak. A variety of spears (sibat), axes, darts (bagakay), and arrows (pana/busog) are also utilized by all ethnic groups in the country.[171]

Kampilan sword from Sulu

Kampilan sword from Sulu Basih weapons

Basih weapons.jpg.webp) Yakan ceremonial swords

Yakan ceremonial swords Lumad swords from Mindanao and Igorot axes from Luzon

Lumad swords from Mindanao and Igorot axes from Luzon Kalis sword from Sulu

Kalis sword from Sulu.jpg.webp) Moro swords

Moro swords War, ceremonial, and fishing spears in the Philippines

War, ceremonial, and fishing spears in the Philippines_badao_daggers.jpg.webp) Lumad daggers in Mindanao

Lumad daggers in Mindanao Swords from Luzon and Visayas

Swords from Luzon and Visayas Ancient swords

Ancient swords Some types of balisong

Some types of balisong Swords from Iloilo in the Visayas

Swords from Iloilo in the Visayas Various swords from the Visayas

Various swords from the Visayas Luzon swords

Luzon swords Swords from Antique in the Visayas

Swords from Antique in the Visayas

Martial arts

Filipino martial arts vary from ethnic group to ethnic group due to the diversity of cultures within the archipelago. The most famous is Arnis (also called kali and eskrima), the national sport and martial art of the Philippines, which emphasize weapon-based fighting styles with sticks, knives, bladed weapons and various improvised weapons as well as open hand techniques. Arnis has met various cultural changes throughout history, where it was also known as estoque, estocada, and garrote during the Spanish occupation. Spanish recorderd first encountered the prevalent martial art as paccalicali-t to the Ibanags, didya/kabaroan) to the Ilocanos, sitbatan/kalirongan to Pangasinenses, sinawali ("to weave") to the Kapampangans, calis/pananandata (use of weapons) to the Tagalogs, pagaradman to the Ilonggos, and kaliradman to the Cebuanos.[172]

Unarmed martial techniques include Pangamot of the Bisaya, suntukan of the Tagalog, Rizal's sikaran of the Tagalog, dumog of the Karay-a, buno of the Igorot people, and yaw-yan. Some impact martial weapons include baston or olisi, bangkaw or tongat, dulo-dulo, and tameng. Edged martial weapons include daga/cuchillo which utilizes gunong, punyal and barung or barong, balisong, karambit which used blades similar to tiger claws, espada which utilizes kampilan, ginunting, pinuti and talibong, itak, kalis which uses poison-bladed daggers known as kris, golok, sibat, sundang, lagaraw, ginunting, and pinunting. Flexible martial weapons include latigo, buntot pagi, lubid, sarong, cadena or tanikala, tabak-toyok. Some projectile martial weapons include pana, sibat, sumpit, bagakay, tirador or pintik/saltik, kana, lantaka, and luthang.[173][174][175] There are also martial arts practiced traditionally in the Philippines and neighboring Austronesian countries as related arts such as kuntaw and silat.[176][177][178]

Kalasag, shields used in Filipino warfare

Kalasag, shields used in Filipino warfare Arnis being taught in Australia

Arnis being taught in Australia Sambal warriors specializing in archery and falconry, recorded in the Boxer Codex

Sambal warriors specializing in archery and falconry, recorded in the Boxer Codex Tboli people utilizing a martial art into a festival dance

Tboli people utilizing a martial art into a festival dance A martial artist wielding an arnis or eskrima

A martial artist wielding an arnis or eskrima Suntukan sequence

Suntukan sequence Kuntaw utilized in dance

Kuntaw utilized in dance Statue depicting the sikaran

Statue depicting the sikaran Jendo[179]

Jendo[179]

Culinary arts

Filipino cuisine is composed of the cuisines of more than a hundred ethnolinguistic groups found within the Philippine archipelago. The majority of mainstream Filipino dishes that compose Filipino cuisine are from the cuisines of the Bikol, Chavacano, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Maranao, Pangasinan, Cebuano (or Bisaya), Tagalog, and Waray ethnolinguistic tribes. The style of cooking and the food associated with it have evolved over many centuries from their Austronesian origins to a mixed cuisine of Indian, Chinese, Spanish, and American influences, in line with the major waves of influence that had enriched the cultures of the archipelago, as well as others adapted to indigenous ingredients and the local palate.[180] Dishes range from the very simple, like a meal of fried salted fish and rice, to the complex paellas and cocidos created for fiestas of Spanish origin. Popular dishes include: lechón[181] (whole roasted pig), longganisa (Philippine sausage), tapa (cured beef), torta (omelette), adobo (chicken or pork braised in garlic, vinegar, oil and soy sauce, or cooked until dry), kaldereta (meat in tomato sauce stew), mechado (larded beef in soy and tomato sauce), puchero (beef in bananas and tomato sauce), afritada (chicken or pork simmered in tomato sauce with vegetables), kare-kare (oxtail and vegetables cooked in peanut sauce), pinakbet (kabocha squash, eggplant, beans, okra, and tomato stew flavored with shrimp paste), crispy pata (deep-fried pig's leg), hamonado (pork sweetened in pineapple sauce), sinigang (meat or seafood in sour broth), pancit (noodles), and lumpia (fresh or fried spring rolls).[182]

Sisig, usually served in scorching metal plates

Sisig, usually served in scorching metal plates Bibingka, a popular Christmas rice cake with salted egg and grated coconut toppings

Bibingka, a popular Christmas rice cake with salted egg and grated coconut toppings Halo-halo, a common Filipino dessert or summer snack

Halo-halo, a common Filipino dessert or summer snack_-_Philippines_2.jpg.webp)

Chicken adobo on rice

Chicken adobo on rice

_02.jpg.webp) Atchara, a type of pickled papaya used as a palate cleanser

Atchara, a type of pickled papaya used as a palate cleanser Kaldereta, a stew usually cooked using goat meat

Kaldereta, a stew usually cooked using goat meat Sinigang, a sour soup with meat and vegetables

Sinigang, a sour soup with meat and vegetables Lechon, whole roasted pig, stuffed with spices

Lechon, whole roasted pig, stuffed with spices Lumpiang ubod, a type of unfried vegetable lumpia

Lumpiang ubod, a type of unfried vegetable lumpia

Other traditional arts

Shell crafts are prevalent throughout the Philippines due to the vast array of mollusk shells available within the archipelago. The shell industry in the country prioritizes crafts made of capiz shells, which are seen in various products ranging from windows, statues, lamps, and many others.[151] Lantern-making is also a traditional art form in the country. The art began after the introduction of Christianity, and many lanterns (locally called parol) appear in Filipino streets and in front of houses, welcoming the Christmas season, which usually begins in September and ends in January in the Philippines, creating the longest Christmas season of any country in the world. A notable festival celebrating Christmas and lanterns is the Giant Lantern Festival, which exhibits gigantic lanterns crafted by Filipino artisans.[183] The art of pyrotechnics is popular in the country during the New Year celebrations and the days before it during the Christmas season. Since 2010, the Philippines has been hosting the Philippine International Pyromusical Competition, the world's largest pyrotechnic competition, previously called the World Pyro Olympics.[184] Lacquerware is an introduced art form in the Philippines. Although prized, only a few Filipino artisans have ventured into the art form. Filipino researchers are recently studying the possibility of turning coconut oil in lacquer.[185][186][187] Paper arts are prevalent in many communities in the Philippines. Some examples of paper art include the taka papier-mâché of Laguna and the pabalat craft of Bulacan.[188] One form of leaf folding art in the country is the puni, which utilizes palm leaves to create various forms such as birds and insects.[188] Bamboo arts are widespread in the country, with various products being made of bamboo from kitchen utensils, toys, furniture, to musical instruments such as the Las Piñas Bamboo Organ, the world's oldest and only organ made of bamboo.[189] A notable bamboo art is the bulakaykay, which bamboos are intentionally bristled to create elaborate and large arches.[188] Floristry is a fine art that continues to be popular during certain occasions such as festivals, birthdays, and Undas.[190] The art of leaf speech, including its language and its deciphering, is a notable art among the Dumagat people, who use a mixture of leaves to express themselves to others and to send secret messages.[191] The art of shamanism and its related arts such as medicinal and healing arts are found in all ethnic groups throughout the country, with each group having their own unique concepts of shamanism and healing practices. Philippine shamans are regarded as sacred by their respective ethnic groups. The introduction of Abrahamic religions, by way of Islam and Christianity, downgraded many shamanitic traditions, with Spanish and American colonizers demeaning the native faiths during the colonial era. Shamans and their practices continue in certain places in the country, although conversions to Abrahamic faiths continue to interfere with their indigenous life-ways.[192] The art of constellation and cosmic reading and interpretation is a fundamental tradition among all Filipino ethnic groups, as the stars are used to interpret the world's standing for communities to conduct proper farming, fishing, festivities, and other important activities. A notable constellation with varying versions among Filipino ethnic groups include Balatik and Moroporo.[193] Another cosmic reading is the utilization of earthly monuments, such as the Gueday stone calendar of Besao, which the locals use to see the arrival of kasilapet, which signals the end of the current agricultural season and the beginning of the next cycle.[194]

Capiz shell window

Capiz shell window Typical shell lamp in the Philippines

Typical shell lamp in the Philippines.jpg.webp) Fireworks in Metro Manila

Fireworks in Metro Manila A huge lantern during the Giant Lantern Festival

A huge lantern during the Giant Lantern Festival Traditional bamboo and paper lanterns, sometimes made with bamboo and capiz shells as well

Traditional bamboo and paper lanterns, sometimes made with bamboo and capiz shells as well Traditional leaf lantern

Traditional leaf lantern Taka, a type of papier-mâché art in Laguna

Taka, a type of papier-mâché art in Laguna Lacquered sewing box

Lacquered sewing box One form of sampaguita garland-making

One form of sampaguita garland-making A traditional floral arrangement for the dead

A traditional floral arrangement for the dead

.jpg.webp) Itneg shaman renewing an offering to a spirit shield

Itneg shaman renewing an offering to a spirit shield Depiction of shamanhood in the Visayas

Depiction of shamanhood in the Visayas Bontoc shaman performing a sacred wake ritual with a death chair

Bontoc shaman performing a sacred wake ritual with a death chair Balatik and Moroporo, native constellations used for farming, fishing, and many other seasonal activities

Balatik and Moroporo, native constellations used for farming, fishing, and many other seasonal activities

Non-traditional arts

The non-traditional arts in the Philippines encompass dance, music, theater, visual arts, literature, film and broadcast arts, architecture and allied arts, and design.[2] There are numerous Filipino specialists or experts on the various fields of non-traditional arts, with those garnering the highest distinctions declared as National Artist, equal to Gawad Manlilika ng Bayan (GAMABA).

Dance

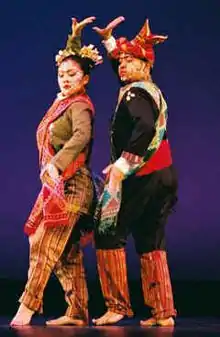

The art of dance under the non-traditional category covers dance choreography, dance direction, and dance performance. Philippine dance is influenced by the folk performing arts of the country, as well as its Hispanic traditions. Many styles also developed due to global influences. Dances of the Igorot dances, such as banga,[76] Moro dances, such as pangalay and singkil,[77] Lumad dances, such as kuntaw and kadal taho and lawin-lawin, Hispanic dances, such as maglalatik and subli, have been inputted into contemporary Filipino dances.[78][79][80][81] Ballet has also become a popular dance form in the Philippines since the early 20th century.[195] Pinoy hip hop music has influenced specific dances in the country, where many have adapted global standards in hip hop and break dances.[196] Many choreographers in the Philippines focus on both traditional and Westernized dances, with certain dance companies focusing on Hispanic and traditional forms of dance.[197][198]

Dancers during the Sinulog Festival

Dancers during the Sinulog Festival Dancers performing Tboli dances in an international stage

Dancers performing Tboli dances in an international stage Filipinos performing Hispanic dances in an international stage

Filipinos performing Hispanic dances in an international stage Dancers during the Pamulinawen

Dancers during the Pamulinawen Performers of Moro dances in an international stage

Performers of Moro dances in an international stage

Music