Climate change in North Korea

Climate change in North Korea is an especially pressing issue. North Korea is highly vulnerable to the effects of global warming due to its weak food security, which in the past has led to widespread famine.[1] The North Korean Ministry of Land and Environmental Protection estimates that North Korea's average temperature rose by 1.9°C between 1918 and 2000.[2]

Background

Politics

North Korea's political ideology of Juche views the environment in the context of socio-political issues, which has resulted in the belief that a revolution from capitalism to communism is necessary to solve environmental issues.[3] As such, the government of North Korea views pollution reduction, effective land management and environmental protection as integral to a socialist society.[3] This led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Law of 1986, which discussed the importance of environmental protection in building communism and outlined the responsibilities of the government and the people in ensuring the preservation of the natural environment, especially in regards to pollution.[4] Climate change has become a feature of anti-American propaganda, with the state media increasingly referencing American obstructionism within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as well as the USA's relatively large greenhouse gas emissions.[5]

Geography and environment

North Korea consists largely of mountains on the north and east coast. The largest range in the North is the Hamgyong Mountains; on the east coast, the Taebaek Mountains extend into South Korea and form the main ridge of the Korean peninsula.[6] These mountains form the country's largest watershed, where rivers such as the Yalu, Tumen and Taedong flow into the Korea Bay and the Sea of Japan.[6] By contrast, North Korea's plains are relatively small, with the largest - the Pyongyang and Chaeryŏng plains - each covering roughly 500 km2.[6]

In the 2013 edition of Germanwatch's Climate Risk Index, North Korea was judged to be the seventh hardest hit by climate-related extreme weather events of 179 nations during the period 1992–2011.[7]

Effects

Impacts on agriculture

Climate change in North Korea has had the greatest impact on agriculture and food production - according to Paul Chisholm of NPR:[8]

The roots of what is known as "food insecurity" lie partly in the geography and climate of the country. Mountains cover most of the nation, leaving few places to farm. North Korea is also beset by widespread erosion and frequent drought. In addition, many of the country's farmers do not have access to modern agricultural machinery like tractors and combines. Add it all up, and you're left with a country that is reliant on neighbors for much of its food.

In its Environment and Climate Change Outlook Report, the North Korean government acknowledge that extreme weather events, such as droughts and flooding, pest outbreaks, forest and land mismanagement and industrial activities have degraded soil productivity on a large scale.[9] Additionally, there was an increasingly significant variation in seasonal temperature between 1918 and 2000, with winter temperatures increasing by an average of 4.9°C and spring temperatures by an average of 2.4°C.[2] In contrast to other scientific observations, the North Korean government views this as beneficial to agriculture, as the growing season is becoming more extended and agricultural growing conditions are improving.[2] However, these benefits aren't reflected in the DPRK's current food production - according to a report by the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization, North Korea would require 641,000 tonnes in food aid, up by 40.57% from the previous year.[10]

Food security

As a result of the impacts of climate change on North Korea's agricultural production, there has been a considerable reduction in food security for North Korean citizens. The famine that ran from 1994 to 1998 was largely caused and exacerbated by withdrawal of aid from allies, flooding and failed food distribution systems, and is estimated to have caused between 240,000 and 2 million deaths.[8] [11] Following an 18-month drought in 2014, the North Korean government declared national emergencies in 2017 and 2018 due to low food production in key provinces, resulting in major shortages across the country.[12] As a result of these climate change-induced food shortages, the Red Cross estimates that 10.3 million North Koreans are undernourished and 20% of children under the age of 5 face stunted physical and cognitive growth as a result of malnourishment.[12]

Sea level rise

In its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions under the UNFCCC, North Korea reports that sea levels are projected to rise by 0.67m to 0.89m by 2100, which it estimates will cause a coastline retreat of 67m to 89m on the East Coast and 670m to 890m on the West Coast.[13] In its Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, the United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that rising sea levels will have major impacts on flooding, coastal erosion and soil salinity,[14] changes in which would further damage North Korea's farmlands.

Political stability

Despite concerns of unrest following the death of Supreme Leader Kim Jong-Il in 2011, Kim Jong-Un has been able to achieve domestic stability through an aggressive foreign policy and the establishment of advisory agencies and committees;[15] however, climate change is posing a risk to this stability. North Korean totalitarianism, which is based on total control by the state, is largely unable to deal with major disruptions to economic growth, food production and energy generation resulting from climate change as totalitarian control requires more resources than more common decentralised governance.[16] In years to come, North Korea will experience greater migration, government corruption and even the erosion of the Juche ideology itself as a result of climate change.[16]

Government response

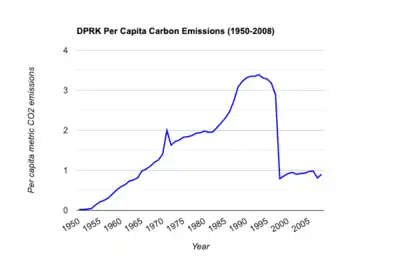

As a party to the UNFCCC,[17] North Korea has ratified both the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris climate agreement. Under the Paris agreement, North Korea has pledged to an 8% reduction of its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030; however, it notes that with international financial support and investment, it could achieve a 40.25% reduction in the same time period.[18] This compliance and international cooperation on climate change comes partially from a genuine concern for environmental protection, but is also a vehicle for receiving foreign assistance and aid - Benjamin Habib, a prominent scholar on North Korea, notes that this international compliance is a result of the parallels between international climate politics and the survival imperatives of the DPRK's government.[19]

North Korea has registered several Clean Development Mechanism projects to the UNFCCC in order to reduce its emissions - these include hydropower stations and methane reduction programs.[5] These projects have been facilitated by $752,000 in UN funding which was approved in December 2019 and will allow the North Korean government to address the structural barriers to its engagement in climate mitigation.[20][21]

References

- Eunjee, Kim (23 November 2015). "Experts: N. Korea Especially Vulnerable to Effects of Climate Change". Voa News. Voice of America. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Ministry of Land and Environment Protection (2012). Democratic People's Republic of Korea Environment and Climate Change Outlook (Report). Ministry of Land and Environment Protection. p. 75. ISBN 978-9946-1-0170-5. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Nam, Sangmin (2003). "The Legal Development of the Environmental Policy in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". Fordham International Law Journal. 27 (4): 1323–1327. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Sangmin, Name (2003). "The Legal Development of the Environmental Policy in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". Fordham International Law Journal. 27 (4): 1330–1332. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Habib, Benjamin (8 September 2012). "North Korea, Climate Mitigation and the Global Commons". Sino-NK. Sino-NK. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Worden, Rober L. (2008). North Korea: a country study (PDF) (5 ed.). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-8444-1188-0. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Harmeling, Sven; Eckstein, David (November 2012). Baum, Daniela; Kier, Gerold (eds.). Global Climate Risk Index 2013 (PDF) (Report). Germanwatch e.V. ISBN 978-3-943704-04-4.

- Chisholm, Paul (19 June 2018). "The Food Insecurity of North Korea". NPR. npr. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Ministry of Land and Environment Protection (2012). Democratic People's Republic of Korea Environment and Climate Change Outlook (Report). Ministry of Land and Environment Protection. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-9946-1-0170-5. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- "N. Korea food production down in 2018: UN body". France24. AFP. 13 December 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Bae, Joonbum (2018). "The North Korean Regime, Domestic Instability and Foreign Policy". North Korean Review. 14 (1): 91. JSTOR 26396135.

- International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (29 April 2019). DPR Korea: Drought and Food Insecurity - Information bulletin (Report). IFRC.

- Government of the Democratic People's Republic of North Korea (September 2016). Intended Nationally Determined Contribution of Democratic People's Republic of Korea (PDF) (Report). Government of the Democratic People's Republic of North Korea. p. 11. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Oppenheimer, Michael; Glavovic, Bruce C.; Hinkel, Jochen; van de Wal, Roderik; Magnan, Alexander K.; Abd-Elgawad, Amro; Cai, Rongshuo; Cifuentes-Jara, Miguel; DeConto, Robert M.; Ghosh, Tuhin; Hay, John; Isla, Federico; Marzeion, Ben; Meyssignac, Benoit & Sebesvari, Zita (2019). "Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities" (PDF). In Abe-Ouchi, Ayako; Gupta, Kapil & Pereira, Joy (eds.). IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. IPCC. p. 375.

- Ahn, Mun Suk (2013). "How Stable Is the New Kim Jong-un Regime?". Problems of Post-Communism. 60 (1): 20. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216600102. S2CID 153435615.

- Habib, Benjamin (2010). "Climate Change and Regime Perpetuation in North Korea". Asian Survey. 50 (2): 396–400. doi:10.1525/as.2010.50.2.378.

- Habib, Benjamin (20 May 2014). "North Korea: an unlikely champion in the fight against climate change". Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Government of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (September 2016). Intended Nationally Determined Contribution of Democratic People's Republic of Korea (PDF) (Report). Government of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. p. 5. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Habib, Benjamin (22 May 2014). "North Korea is shockingly compliant on climate change. Why?". The Week. The Week Publications Inc. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Kim, Jeongmin (27 December 2019). "UN approves $752,000 to help North Korea fight climate change". NK News. NK Consulting Inc. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Readiness Proposal with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) for Democratic People's Republic of Korea (PDF) (Report). UN Green Climate Fund. 13 December 2019. p. 4.