Latimer County, Oklahoma

Latimer County is a county located in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Its county seat is Wilburton.[1] As of the 2010 census, the population was 11,154.[2] The county was created at statehood in 1907 and named for James L. Latimer, a delegate from Wilburton to the 1906 state Constitutional Convention. Prior to statehood, it had been for several decades part of Gaines County, Sugar Loaf County, and Wade County in the Choctaw Nation.[3]

Latimer County | |

|---|---|

| |

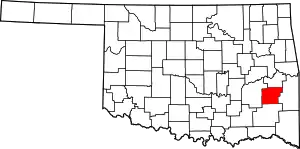

Location within the U.S. state of Oklahoma | |

Oklahoma's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 34°52′N 95°14′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1907 |

| Named for | James L. Latimer |

| Seat | Wilburton |

| Largest city | Wilburton |

| Area | |

| • Total | 729 sq mi (1,890 km2) |

| • Land | 722 sq mi (1,870 km2) |

| • Water | 7.0 sq mi (18 km2) 0.95%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018) | 10,231 |

| • Density | 15/sq mi (6/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

History

This area was occupied for at least 3500 years by cultures of indigenous peoples. The most recent of the prehistoric peoples established complex earthworks during the Mississippian culture. Archeological excavations have revealed artifacts from Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippian cultures. Living in what is now southeastern Oklahoma, these peoples were direct ancestors of the Caddo Nation, a historic confederacy of tribes that flourished in east Texas, Arkansas and northern Louisiana before removal to another area of Indian Territory.[4]

In the 1970s excavations at the McCutchan-McLaughlin site revealed many details about the lives and deaths of the Fourche Maline culture people, who lived in this area in the Woodland Period, about 300 BCE to 800 CE. These hunter-gatherers were physically healthier than later descendants in more complex cultures who depended on maize agriculture, but they were also often beset by warfare. Numerous remains were found in mass graves, killed by arrows or spears. This archeological site continues to be studied and has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[4]

In 1831, the area now known as Latimer County was organized as part of the Choctaw Nation in the Indian Territory after the Choctaw were removed by the federal government from their traditional territory in the American Southeast. Following statehood Latimer County's boundaries were drawn to conform to Oklahoma's township and range system, which uses east–west and north–south lines as land boundaries. The Choctaw Nation, by contrast, divided its counties using easily recognizable landmarks, such as mountains and rivers. The territory of present-day Latimer County had the distinction of being the meeting point of all three administrative super-regions comprising the Choctaw Nation, called the Apukshunubbee District, Moshulatubbee District, and Pushmataha District. Within these three districts the land area of the present-day county fell within Gaines County, Jacksfork County, Sans Bois County, Skullyville County, and Wade County.

In 1858, the Butterfield Overland Mail established a route through the territory, which included stage stops at Edwards's Station (near present Hughes), Holloway's Station (near Red Oak), Riddle's Station (near Lutie) and Pusley's Station near Higgins.[3]

The beginning of large-scale coal mining attracted railroad construction to the area to get the commodity to market. The chief coal mining areas were in the mountains in the north of the county, in the Choctaw Segregated Coal Lands. Coal mining companies were rapidly established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1889–90, the Choctaw Coal and Railway Company (later known as the Choctaw, Oklahoma and Gulf Railroad, and still later as part of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific line) laid 67.4 miles of track from Wister to McAlester. The Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway (Katy) completed a branch line from North McAlester to Wilburton in 1904.[3]

As a prelude to Oklahoma being admitted as a state to the Union, the Dawes Act was extended to the Choctaw and others of the Five Civilized Tribes. These had all been removed from the Southeast. Choctaw tribal control of communal lands was dissolved, and the lands were allotted to individual households of tribal members, in an effort to encourage subsistence farming on the European-American model. The Choctaw lost most of their land, with individuals retaining about one-quarter of the land in the county.[3] The government declared any remaining land to be 'surplus;' it was sold, mostly to non-Natives. Tribal governments were also dissolved, and Oklahoma became a state.

By 1912, the newly organized county had 27 mines; some 3,000 miners produced 5,000 tons of coal per day. Most coal was produced by the large companies. Native-born whites held most of the jobs as miners, but African Americans, European immigrants from the British Isles and Italy, and Mexicans also worked as laborers in the mining industry.[3]

In less than two decades, the coal industry collapsed, due to labor unrest seeking relief from harsh working conditions and unfair labor practices, competition from oils, and the effects of the Great Depression. From 1920 to 1930, the county lost about 2,000 people, who sought work in other areas.[3] By 1932, only one mine still operated in the county. Mining towns lost almost half of their populations, and at one point, 93.5 percent of those remaining in the country were surviving on government relief, through programs started by the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Federal construction projects to build infrastructure and invest for the future provided many jobs for the unemployed. Locally such projects included Wilburton Municipal Airport, schools at Panola and elsewhere, and road-paving works. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), another federal program conducted in collaboration with state governments, developed a park project at the state game preserve, now part of Robbers Cave State Park.[3]

In 1933, Spanish–American War veterans established Veterans Colony in the county, buying land together. The war veterans could build cabins here and grow their own food, living year round in a community. In later years, membership was opened to veterans of all wars. Veterans Colony still operates.[3]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 729 square miles (1,890 km2), of which 722 square miles (1,870 km2) is land and 7.0 square miles (18 km2) (1.0%) is water.[5]

The Sans Bois Mountains span the northern border of the county, while the Winding Stair Mountains extend into its southern part. The Fourche Maline, Brazil and Sans Bois creeks drain the northern part of the county into the Poteau River, a tributary of the Arkansas River. Buffalo and Gaines Creeks drain the southern part into the Kiamichi River, a tributary of the Red River.[3]

Major highways

U.S. Highway 270

U.S. Highway 270 State Highway 1

State Highway 1 State Highway 2

State Highway 2 State Highway 63

State Highway 63 State Highway 82

State Highway 82

Adjacent counties

- Haskell County (north)

- Le Flore County (east)

- Pushmataha County (south)

- Pittsburg County (west)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 11,321 | — | |

| 1920 | 13,866 | 22.5% | |

| 1930 | 11,184 | −19.3% | |

| 1940 | 12,380 | 10.7% | |

| 1950 | 9,690 | −21.7% | |

| 1960 | 7,738 | −20.1% | |

| 1970 | 8,601 | 11.2% | |

| 1980 | 9,840 | 14.4% | |

| 1990 | 10,333 | 5.0% | |

| 2000 | 10,692 | 3.5% | |

| 2010 | 11,154 | 4.3% | |

| 2018 (est.) | 10,231 | [6] | −8.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[7] 1790-1960[8] 1900-1990[9] 1990-2000[10] 2010-2013[2] | |||

As of the census[11] of 2000, there were 10,692 people, 3,951 households, and 2,868 families residing in the county. The population density was 15 people per square mile (6/km2). There were 4,709 housing units at an average density of 6 per square mile (3/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 73.01% White, 0.96% Black or African American, 19.42% Native American, 0.18% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.51% from other races, and 5.91% from two or more races. 1.53% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 20.7% were of American, 9.5% Irish, 8.1% German and 5.0% English ancestry according to Census 2000.

There were 3,951 households, out of which 32.20% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.90% were married couples living together, 11.50% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.40% were non-families. 24.90% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.00.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.70% under the age of 18, 11.40% from 18 to 24, 24.20% from 25 to 44, 22.50% from 45 to 64, and 16.10% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 97.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.70 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $23,962, and the median income for a family was $29,661. Males had a median income of $27,449 versus $19,577 for females. The per capita income for the county was $12,842. About 19.00% of families and 22.70% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.70% of those under age 18 and 16.40% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

Despite the county being home to a significant Native American population and a wide Democratic registration advantage, the county -- like every Oklahoma county since 2000 -- has avoided the party entirely in presidential elections in the 21st century. Following the lead of most rural counties nationwide, the Republican candidate has won at least 60% of the vote in the county since 2008, with Donald Trump topping out at 76.4% in 2016.

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of January 15, 2019[12] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 3,996 | 65.75% | |||

| Republican | 1,495 | 24.59% | |||

| Others | 588 | 9.67% | |||

| Total | 6,079 | 100% | |||

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 76.4% 3,100 | 19.7% 797 | 3.9% 159 |

| 2012 | 69.2% 2,628 | 30.8% 1,170 | |

| 2008 | 68.5% 2,860 | 31.5% 1,313 | |

| 2004 | 56.6% 2,535 | 43.4% 1,945 | |

| 2000 | 47.4% 1,739 | 50.8% 1,865 | 1.8% 65 |

| 1996 | 29.7% 1,189 | 55.5% 2,222 | 14.8% 592 |

| 1992 | 24.8% 1,212 | 53.4% 2,606 | 21.8% 1,067 |

| 1988 | 43.2% 1,830 | 55.9% 2,365 | 0.9% 38 |

| 1984 | 53.9% 2,210 | 45.3% 1,858 | 0.8% 32 |

| 1980 | 43.8% 1,737 | 53.1% 2,105 | 3.1% 124 |

| 1976 | 32.6% 1,312 | 66.1% 2,661 | 1.4% 55 |

| 1972 | 64.8% 2,520 | 31.9% 1,239 | 3.3% 130 |

| 1968 | 32.7% 1,091 | 40.5% 1,350 | 26.8% 892 |

| 1964 | 27.0% 849 | 73.0% 2,297 | |

| 1960 | 48.7% 1,454 | 51.3% 1,534 | |

| 1956 | 41.0% 1,387 | 59.0% 1,994 | |

| 1952 | 42.2% 1,668 | 57.8% 2,283 | |

| 1948 | 26.6% 919 | 73.4% 2,536 | |

| 1944 | 39.8% 1,296 | 59.9% 1,948 | 0.3% 11 |

| 1940 | 33.6% 1,600 | 65.8% 3,138 | 0.6% 28 |

| 1936 | 31.4% 1,344 | 68.2% 2,923 | 0.4% 19 |

| 1932 | 18.9% 728 | 81.1% 3,119 | |

| 1928 | 45.8% 1,368 | 53.0% 1,583 | 1.3% 38 |

| 1924 | 35.9% 971 | 53.9% 1,457 | 10.1% 274 |

| 1920 | 47.9% 1,410 | 40.8% 1,200 | 11.3% 331 |

| 1916 | 33.8% 663 | 48.5% 950 | 17.7% 346 |

| 1912 | 31.1% 482 | 46.6% 722 | 22.3% 345 |

Economy

Coal mining was the basis of the county economy even before statehood, with mines operating by 1895. By 1912, The county 27 mines and about three thousand miners producing 3,000 tons per day. However, the industry collapsed during the 1920s due to labor disputes, competition from petroleum-based fuels and the onset of the Great Depression. Only one mine was still operating in 1933.[3]

Agriculture was primarily limited to vegetables sold in the mining towns. Cotton, corn and cattle were the primary cash crops sold outside the area. After the coal industry collapsed, the main industries were cattle raising, lumbering and production of oil and gas.[3]

Education

In 1909 state government created the Oklahoma School of Mines and Metallurgy at Wilburton, placed centrally within the southeastern Oklahoma mining district. In 2000, as Eastern Oklahoma State College, the school was a two-year, liberal-arts institution.[3]

NRHP sites

The following sites in Latimer County are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

|

|

References

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Everett, Dianna. "Latimer County," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Oklahoma Historical Society, 2009. Accessed April 4, 2015.

- "Latimer County: McCutchan-McLaughlin Site" Archived 2010-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, Oklahoma's Past, Oklahoma Archeological Survey, University of Oklahoma, 2005 (updated 2016); accessed 19 January 2016

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Oklahoma Registration Statistics by County" (PDF). OK.gov. January 15, 2019. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-29.