Meibutsu

Meibutsu (名物; lit. 'famous thing') is a term most often applied to regional specialties (also known as meisan, 名産).

Meibutsu can also be applied to specialized areas of interest, such as chadō, where it refers to famous tea utensils, or Japanese swords, where it refers to specific named famous blades.

Definition

Meibutsu could be classified into the following five categories:[1]

- Tokusanhin, regional Japanese food specialties such as the roasted rice cakes (yakimochi) of Hodogaya, and the yam gruel torojiru of Mariko;

- Japanese crafts as souvenirs such as the swords of Kamakura or the shell-decorated screens of Enoshima;

In the past it also included:

- supernatural souvenirs and wonder-working panaceas, such as the bitter powders of Menoke that supposedly cured a large number of illnesses;

- bizarre things that added a touch of the "exotic" to the aura of each location such as the fire-resistant salamanders of Hakone; and

- the prostitutes, who made localities such as Shinagawa, Fujisawa, Akasaka, Yoshida and Goyu famous. In some cases these people may have encouraged visits to otherwise impoverished and remote localities, contributing to the local economy and the exchange between people of different backgrounds.

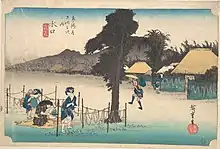

Several prints in various versions of the ukiyo-e series The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō depict meibutsu. These include Arimatsu shibori, a stenciled fabric sold at Narumi (station 41) and Kanpyō (sliced gourd), a product of Minakuchi (station 51), as well as a famous teahouse at Mariko (station 21) and a famous tateba (rest stop) selling a type of rice-cake called ubagamochi at Kusatsu (station 51).

Another category are special tea tools that were historic and precious items of Japanese tea ceremony.

Usage

Evelyn Adam gave the following account of meibutsu in her 1910 book, Behind the Shoji:

The strain of giving would really become unendurable to half the people in Japan were it not for what is known as the "meibutsu" or specialty of each town. This fills in gaps nicely; this provides the answer to vexed questions. "What shall I give to the kind person from whom I have received my twenty-fifth English lesson?" "A meibutsu." "And what shall I send my ailing father-in-law?" "A meibutsu" also, both to be brought back from the next place I happen to visit. The shops there are sure to make a reduction on quantity, well knowing that every person who goes off on a holiday is expected to return with "meibutsu" for everybody he knows, the idea being that a person who has enjoyed himself and had nothing particular to do should try to make up to those left behind in the place where they belong, engaged in the usual dull routine. Help to lift somebody out of the rut by bringing home to him or her some little novelty—that is the kindly spirit—and never mind what the trifle may be. Whether a metal pipe or a bamboo toy, it can be presented with perfect propriety to grandmother or infant grandson.

"Meibutsus" vary greatly of course. Some are sticky like the chestnut paste of Nikko, some are bulky and a source of perpetual anxiety like the fragile baskets of Arima, some are pretty like the Ikao cotton cloth dyed in the iron spring water, and some are useless and ugly and impossible to carry, like the fierce fishes of Kamakura—the fishes which blow themselves up into a globe when angry or excited and then remain blown up—as an eternal punishment I suppose—and get turned into lanterns. There are dozens of all varieties, useful and useless, dear and queer, sensible and silly, so that people with much-travelled acquaintances are soon in a fair way to start a museum. Or, to be accurate, they would be if they kept the things. But nobody does keep them all. The provident housekeeper constantly receiving "meibutsus," and constantly requiring things to send back in return, has invented a system to circumvent the expense. It is somewhat like double entry book-keeping. When the need for the return gift arises, she goes, like old Mother Hubbard, to her cupboard and looks over the parcels that have arrived lately. Distinctive things like blown-up fish may be out of the question, but there are sure to be some local or non-committal contributions. Doubtless there will be eggs hardly a month old yet, and cakes that only came week before last. Either of these will do nicely; therefore the lady wraps them up properly and passes them on. Nine times out of ten, she who receives them does the same; also her friend and her friend's friend, till those eggs or cakes are nearly as travelled as a war correspondent.[2]

Examples

| Prefecture | Traditional Crafts | Agricultural Products | Tokusanhin |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

| ||

|

|||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| |||

|

|

||

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

||

|

|||

|

| ||

|

|||

|

| ||

|

|||

| |||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|||

|

| ||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

| ||

| |||

|

In media

Meibutsu are key to the promotion of tourism within Japan and are frequently depicted in media since the Edo era.

Ukiyo-e

- Meibutsu in Ukiyo-e

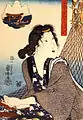

.jpg.webp) Bijin with pumpkin grown at Sunamura by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Bijin with pumpkin grown at Sunamura by Utagawa Kuniyoshi Narumi: Shop Selling Famous Arimatsu Tie-dyed Fabric by Hiroshige

Narumi: Shop Selling Famous Arimatsu Tie-dyed Fabric by Hiroshige Fukuroi: Famous Kites of Tōtōmi Province by Hiroshige

Fukuroi: Famous Kites of Tōtōmi Province by Hiroshige Famous products of Yamashiro Province by Keisai Eisen

Famous products of Yamashiro Province by Keisai Eisen

Manga & Anime

- Ekiben Hitoritabi, food and travel manga about ekiben containing tokusanhin

- Golden Kamuy, a Seinen manga and anime that includes many Ainu meibutsu from Hokkaido including salmon and Ainu cuisine

- Oishii Kamishama (Delicious Venus), a food manga devoted to presenting tokusanhin

- Omae wa Mada Gunma o Shiranai, comedy manga and anime that presents some meibutsu of Gunma including himokawa udon, yakimanju, hoshi-imo (wind dried sweet potato), and miso pan

- Yatogame-chan Kansatsu Nikki, comedy manga and anime that presents some meibutsu of Nagoya

Television

- Japanese Style Originator - variety show that presents meibutsu and traditional craftsman as regular segments

See also

References

- According to a paper by Laura Nenzi cited by Jilly Traganou in The Tokaido Road: Traveling and Representation in Edo and Meiji Japan (Routledge, 2004), (72)

- Evelyn Adam, Behind the Shoji (London: Methuen, 1910), 185–187.