Multiculturalism in Canada

Multiculturalism in Canada was officially adopted by the government during the 1970s and 1980s.[1] The Canadian federal government has been described as the instigator of multiculturalism as an ideology because of its public emphasis on the social importance of immigration.[2][3] The 1960s Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism is often referred to as the origin of modern political awareness of multiculturalism.[4]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Canada |

|---|

|

| History |

| Topics |

| Research |

|

Canadians have used the term "multiculturalism" in different ways: descriptively (as a sociological fact), prescriptively (as ideology) or politically (as policy).[5][6] In the first sense "multiculturalism" is a description of the many different religious traditions and cultural influences that in their unity and coexistence result in a unique Canadian cultural mosaic.[6] The nation consists of people from a multitude of racial, religious and cultural backgrounds and is open to cultural pluralism.[7] Canada has experienced different waves of immigration since the nineteenth century, and by the 1980s almost 40 percent of the population were of neither British nor French origins (the two largest groups, and among the oldest).[8] In the past, the relationship between the British and the French has been given a lot of importance in Canada's history. By the early twenty-first century, people from outside British and French heritage composed the majority of the population, with an increasing percentage of individuals who identify themselves as "visible minorities".

Multiculturalism is reflected with the law through the Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1988 and section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and is administered by the Department of Canadian Heritage. The Broadcasting Act of 1991 asserts the Canadian broadcasting system should reflect the diversity of cultures in the country. Despite the official policies, a small segment of the Canadian population are critical of the concept(s) of a cultural mosaic and implementation(s) of multiculturalism legislation.[9] Quebec's ideology differs from that of the other provinces in that its official policies focus on interculturalism.[10]

Historical context

In the 21st century Canada is often characterised as being "very progressive, diverse, and multicultural".[11] However, Canada until the 1940s saw itself in terms of English and French cultural, linguistic and political identities, and to some extent indigenous.[12] European immigrants speaking other languages, such as Canadians of German ethnicity and Ukrainian Canadians, were suspect, especially during the First World War when thousands were put in camps because they were citizens of enemy nations.[13] Jewish Canadians were also suspect, especially in Quebec where anti-semitism was a factor and the Catholic Church of Quebec associated Jews with modernism, liberalism, and other unacceptable values.[14]

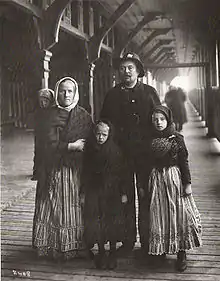

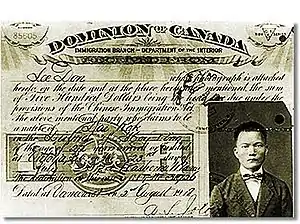

Asians encountered legal obstacles limiting immigration during the 1800s and early 1900s.[15][16] Additional, specific ethnic groups that did immigrate during this time faced barriers within Canada preventing full participation in political and social matters, including equal pay and the right to vote.[17] While black ex-slave refugees from the United States had been tolerated, racial minorities of African or Asian origin were generally believed "beyond the pale" (not acceptable to most people).[18] Although this mood started to shift dramatically during the Second World War,[19][20] Japanese Canadians were interned during the overseas conflict and their property confiscated.[21] Prior to the advent of the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960 and its successor the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, the laws of Canada did not provide much in the way of civil rights and it was typically of limited concern to the courts.[22] Since the 1960s, Canada has placed emphasis on equality and inclusiveness for all people.[23][24]

Immigration

Immigration has played an integral part in the development of multiculturalism within Canada during the last half of the 20th century.[25] Legislative restrictions on immigration (such as the Continuous journey regulation and Chinese Immigration Act) that had favoured British, American and European immigrants were amended during the 1960s, resulting in an influx of diverse people from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean.[26] The number of people who are becoming immigrants is steadily increasing as seen between 2001 and 2006, the number of foreign-born people increased by 13.6%.[27] By 2006 Canada had grown to have thirty four ethnic groups with at least one hundred thousand members each, of which eleven have over 1,000,000 people and numerous others are represented in smaller amounts.[28] 16.2% of the population identify themselves as a visible minority.[28]

Canada currently has one of the highest per capita immigration rate in the world, driven by economic policy and family reunification.[29] Canada also resettles over one in ten of the world's refugees.[30] In 2008, there were 65,567 immigrants in the family class, 21,860 refugees, and 149,072 economic immigrants amongst the 247,243 total immigrants to the country.[31] Approximately 41% of Canadians are of either the first or second-generation.[31] One out of every five Canadians currently living in Canada was born out of the country.[32] The Canadian public as well as the major political parties support immigration.[33] Political parties are cautious about criticizing the high level of immigration, because, as noted by The Globe and Mail, "in the early 1990s, the Reform Party" was branded 'racist' for suggesting that immigration levels be lowered from 250,000 to 150,000."[34][35] The party was also noted for their opposition to government-sponsored multiculturalism.[36]

Settlement

Culturally diverse areas or "ethnic enclaves" are another way in which multiculturalism has manifested. Newcomers have tended to settle in the major urban areas.[37] These urban enclaves have served as a home away from home for immigrants to Canada, while providing a unique experience of different cultures for those of long Canadian descent. In Canada, there are several ethnocentric communities with many diverse backgrounds, including Chinese, Indian, Italian and Greek.[38] Canadian Chinatowns are one of the most prolific type of ethnic enclave found in major cities.[38] These areas seemingly recreate an authentic Chinese experience within an urban community. During the first half of the 20th century, Chinatowns were associated with filth, seediness, and the derelict.[38] By the late 20th century, Chinatown(s) had become areas worth preserving, a tourist attraction.[38] They are now generally valued for their cultural significance and have become a feature of most large Canadian cities.[38] Professor John Zucchi of McGill University states:[38]

Unlike earlier periods when significant ethnic segregation might imply a lack of integration and therefore be viewed as a social problem, nowadays ethnic concentration in residential areas is a sign of vitality and indicates that multiculturalism as a social policy has been successful, that ethnic groups are retaining their identities if they so wish, and old-world cultures are being preserved at the same time that ethnic groups are being integrated. In addition these neighbourhoods, like their cultures, add to the definition of a city and point to the fact that integration is a two-way street."

Evolution of federal legislation

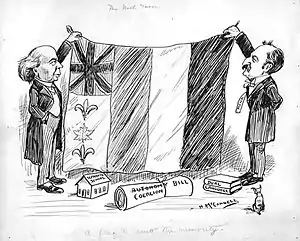

The Quebec Act, implemented after the British conquest of New France in the mid-1700s brought a large Francophone population under British Imperial rule, creating a need for accommodation.[39] A century later the compromises made between the English and French speaking Fathers of Confederation set Canada on a path to bilingualism, and this in turn contributed to biculturalism and the acceptance of diversity.[40]

The American writer Victoria Hayward in the 1922 book about her travels through Canada, described the cultural changes of the Canadian Prairies as a "mosaic".[41] Another early use of the term mosaic to refer to Canadian society was by John Murray Gibbon, in his 1938 book Canadian Mosaic.[42] The mosaic theme envisioned Canada as a "cultural mosaic" rather than a "melting pot".[43]

Charles Hobart a sociologist from the University of Alberta,[44] and Lord Tweedsmuir the 15th Governor General of Canada were early champions of the term multiculturalism.[45] From his installation speech in 1935 onwards, Lord Tweedsmuir maintained in speeches and over the radio recited his ideas that ethnic groups "should retain their individuality and each make its contribution to the national character," and "the strongest nations are those that are made up of different racial elements."[46] Adélard Godbout, while Premier of Quebec in 1943, published an article entitled "Canada: Unity in Diversity" in the Council on Foreign Relations journal discussing the influence of the Francophone population as a whole.[47] The phrase "Unity in diversity" would be used frequently during Canadian multiculturalism debates in the proceeding decades.[48][49]

The beginnings of the development of Canada's contemporary policy of multiculturalism can be traced to the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, which was established on July 19, 1963 by the Liberal government of Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson in response to the grievances of Canada's French-speaking minority.[11] The report of the Commission advocated that the Canadian government should recognize Canada as a bilingual and bicultural society and adopt policies to preserve this character.[11]

The recommendations of this report elicited a variety of responses. Former Progressive Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, (who was now Leader of the Official Opposition after his government was succeeded by that of Pearson on April 22, 1963), viewed them as an attack on his "One Canada Policy" that was opposed to extending accommodation to minority groups.[50] The proposals also failed to satisfy those Francophones in the Province of Quebec who gravitated toward Québécois nationalism.[51] Additionally, Canadians of neither English nor French descent (so-called "Third Force" Canadians) advocated that a policy of "multiculturalism" would better reflect the diverse heritage of Canada's peoples.[52][53]

Paul Yuzyk, a Progressive Conservative Senator of Ukrainian descent, referred to Canada as "a multicultural nation" in his influential maiden speech in 1964, creating much national debate, and is remembered for his strong advocacy of the implementation of a multiculturalism policy and Social liberalism.[54]

On October 8, 1971, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau announced in the House of Commons that, after much deliberation, the policies of bilingualism and multiculturalism would be implemented in Canada.[55] The next day, Prime Minister Trudeau reiterated the Canadian government's support for "cultivation and use of many languages" at the 10th Congress of the Ukrainian Canadian Committee in Winnipeg. Trudeau espoused participatory democracy as a means of making Canada a "Just Society".[56][57] Trudeau stated:[57]

Uniformity is neither desirable nor possible in a country the size of Canada. We should not even be able to agree upon the kind of Canadian to choose as a model, let alone persuade most people to emulate it. There are few policies potentially more disastrous for Canada than to tell all Canadians that they must be alike. There is no such thing as a model or ideal Canadian. What could be more absurd than the concept of an “all-Canadian” boy or girl? A society which emphasizes uniformity is one which creates intolerance and hate. A society which eulogizes the average citizen is one which breeds mediocrity. What the world should be seeking, and what in Canada we must continue to cherish, are not concepts of uniformity but human values: compassion, love, and understanding.

When the Canadian constitution was patriated by Prime Minister Trudeau in 1982, one of its constituent documents was the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and section 27 of the Charter stipulates that the rights laid out in the document are to be interpreted in a manner consistent with the spirit of multiculturalism.[58]

The Canadian Multiculturalism Act was introduced during the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney, and received Royal Assent on July 21, 1988.[59] On a practical level, a result of the Multiculturalism Act was that federal funds began to be distributed to ethnic groups to help them preserve their cultures, leading to such projects as the construction of community centres.[60]

In June 2000 Prime Minister Jean Chrétien stated:[61]

Canada has become a post-national, multicultural society. It contains the globe within its borders, and Canadians have learned that their two international languages and their diversity are a comparative advantage and a source of continuing creativity and innovation. Canadians are, by virtue of history and necessity, open to the world.

With this in mind on November 13, 2002, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien designated, by Royal Proclamation, June 27 of each year Canadian Multiculturalism Day.[62]

Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Section Twenty-seven of the Charter states that:[58]

This Charter shall be interpreted in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of the multicultural heritage of Canadians.

Section Fifteen of the Charter that covers equality states:[63]

Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age, or mental or physical disability.

Canadian Multiculturalism Act

The 1988 Canadian Multiculturalism Act affirms the policy of the government to ensure that every Canadian receives equal treatment by the government which respects and celebrates diversity.[58] The "Act" in general recognizes:[64]

- Canada's multicultural heritage and that that heritage must be protected.

- The rights of indigenous peoples.

- English and French remain the only official languages, however other languages may be used.

- Social equality within society and under the law regardless of race, colour, ancestry, national or ethnic origin, creed or religion.

- Minorities' rights to enjoy their cultures.

Section 3 (1) of the act states:[58]

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the Government of Canada to

(a) recognize and promote the understanding that multiculturalism reflects the cultural and racial diversity of Canadian society and acknowledges the freedom of all members of Canadian society to preserve, enhance and share their cultural heritage

(b) to recognize and promote the understanding that multiculturalism is a fundamental characteristic of the Canadian heritage and identity and that it provides an invaluable resource in the shaping of Canada's future

Broadcasting Act

In the Multiculturalism Act, the federal government proclaimed the recognition of the diversity of Canadian culture.[65] Similarly the Broadcasting Act of 1991 asserts the Canadian broadcasting system should reflect the diversity of cultures in the country.[66] The CRTC is the governmental body which enforces the Broadcasting Act.[66] The CRTC revised their Ethnic Broadcasting Policy in 1999 to go into the details on the conditions of the distribution of ethnic and multilingual programming.[65] One of the conditions that this revision specified was the amount of ethnic programming needed in order to be awarded the ethnic broadcasting licence. According to the act, 60% of programming on a channel, whether on the radio or television, has to be considered ethnic in order to be approved for the licence under this policy.[65]

Provincial legislation and policies

All ten of Canada's provinces have some form of multiculturalism policy.[67] At present, six of the ten provinces – British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Quebec, and Nova Scotia – have enacted multiculturalism legislation. In eight provinces – British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia – a multiculturalism advisory council reports to the minister responsible for multiculturalism. In Alberta, the Alberta Human Rights Commission performs the role of multiculturalism advisory council. In Nova Scotia, the Act is implemented by both a Cabinet committee on multiculturalism and advisory councils. Ontario has an official multicultural policy and the Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration is responsible for promoting social inclusion, civic and community engagement and recognition. The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador launched the province's policy on multiculturalism in 2008 and the Minister of Advanced Education and Skills leads its implementation.

While the territorial governments do not have multiculturalism policies per se, they have human rights acts that prohibit discrimination based on, among other things, race, colour, ancestry, ethnic origin, place of origin, creed or religion. In Whitehorse, the Multicultural Centre of the Yukon provides services to immigrants.[67]

British Columbia

British Columbia legislated the Multiculturalism Act in 1993.[67] The purposes of this act (s. 2) are:[68]

- to recognize that the diversity of British Columbians as regards race, cultural heritage, religion, ethnicity, ancestry and place of origin is a fundamental characteristic of the society of British Columbia that enriches the lives of all British Columbians;

- to encourage respect for the multicultural heritage of British Columbia;

- to promote racial harmony, cross cultural understanding and respect and the development of a community that is united and at peace with itself;

- to foster the creation of a society in British Columbia in which there are no impediments to the full and free participation of all British Columbians in the economic, social, cultural and political life of British Columbia.

Alberta

Alberta primarily legislated the Alberta Cultural Heritage Act in 1984 and refined it with the Alberta Multiculturalism Act in 1990.[67] The current legislation pertaining to multiculturalism is The Human Rights, Citizenship and Multiculturalism Act that passed in 1996.[67] This current legislation deals with discrimination in race, religious beliefs, colour, gender, physical disability, age, marital status and sexual orientation, among other things.[69] Alberta Human Rights chapter A‑25.5 states:[70]

- multiculturalism describes the diverse racial and cultural composition of Alberta society and its importance is recognized in Alberta as a fundamental principle and a matter of public policy;

- it is recognized in Alberta as a fundamental principle and as a matter of public policy that all Albertans should share in an awareness and appreciation of the diverse racial and cultural composition of society and that the richness of life in Alberta is enhanced by sharing that diversity; and

- it is fitting that these principles be affirmed by the Legislature of Alberta in an enactment whereby those equality rights and that diversity may be protected.

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan was the first Canadian province to adopt legislation on multiculturalism.[67] This piece of legislation was called The Saskatchewan Multiculturalism Act of 1974, but has since been replaced by the new, revised Multiculturalism Act (1997).[67] The purposes of this act (s. 3) are similar to those of British Columbia:[71]

- to recognize that the diversity of Saskatchewan people with respect to race, cultural heritage, religion, ethnicity, ancestry and place of origin is a fundamental characteristic of Saskatchewan society that enriches the lives of all Saskatchewan people;

- to encourage respect for the multicultural heritage of Saskatchewan;

- to foster a climate for harmonious relations among people of diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds without sacrificing their distinctive cultural and ethnic identities;

- to encourage the continuation of a multicultural society.

The motto of the province of Saskatchewan, adopted in 1986, is Multis e gentibus vires (“from many peoples, strength” or “out of many peoples, strength”).[72]

Manitoba

Manitoba's first piece of legislation on multiculturalism was the Manitoba Intercultural Council Act in 1984.[67] However, in the summer on 1992, the province developed a new provincial legislation called the Multiculturalism Act.[67] The purposes of this act (s. 2) are to:[73]

- recognize and promote understanding that the cultural diversity of Manitoba is a strength of and a source of pride to Manitobans;

- recognize and promote the right of all Manitobans, regardless of culture, religion or racial background, to: (i) equal access to opportunities, (ii) participate in all aspects of society, and (iii) respect for their cultural values; and

- enhance the opportunities of Manitoba's multicultural society by acting in partnership with all cultural communities and by encouraging cooperation and partnerships between cultural communities

Ontario

Ontario had a policy in place in 1977 that promoted cultural activity, but formal legislation for a Ministry of Citizenship and Culture (now known as Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration) only came to fruition in 1982.[67] The Ministry of Citizenship and Culture Act (1990) (s. 4) states its purpose:[74]

- to encourage full, equal and responsible citizenship among the residents of Ontario;

- recognizing the pluralistic nature of Ontario society, to stress the full participation of all Ontarians as equal members of the community, encouraging the sharing of cultural heritage while affirming those elements held in common by all residents;

- to ensure the creative and participatory nature of cultural life in Ontario by assisting in the stimulation of cultural expression and cultural preservation;

- to foster the development of individual and community excellence, enabling Ontarians to better define the richness of their diversity and the shared vision of their community.

Quebec

Quebec differs from the rest of the nine provinces in that its policy focuses on "interculturalism"- rather than multiculturalism,[75][76][77] where diversity is strongly encouraged,[78] but only under the notion that it is within the framework that establishes French as the public language.[79] Immigrant children must attend French language schools; most signage in English-only is banned (but bilingual signage is common in many communities).[67]

In 1990, Quebec released a White paper called Lets Build Quebec Together: A Policy Statement on Integration and Immigration which reinforced three main points:[80]

- Quebec is a French-speaking society

- Quebec is a democratic society in which everyone is expected to contribute to public life

- Quebec is a pluralistic society that respects the diversity of various cultures from within a democratic framework

In 2005, Quebec passed legislation to develop the Ministry of Immigration and Cultural Communities, their functions were:[67]

- to support cultural communities in order to facilitate their full participation in Quebec society

- to foster openness to pluralism; and

- to foster closer intercultural relations among the people of Quebec.

In 2015, when the Coalition Avenir Quebec (CAQ) took a nationalist turn, they advocated for "exempting Quebec from the requirements of multiculturalism.".[81] One of the key priorities for the CAQ when elected in 2018 Quebec election was reducing the number of immigrants, to 40,000 annually; a 20 per cent reduction.[82]

New Brunswick

New Brunswick first introduced their multicultural legislation in 1986.[67] The policy is guided by four principles: equality, appreciation, preservation of cultural heritages and participation.[83] In the 1980s the provincial government developed a Ministerial Advisory Committee to provide assistance to the minister of Business in New Brunswick, who is in turn responsible for settlement and multicultural communities.[67]

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia introduced their multicultural legislation, the Act to Promote and Preserve Multiculturalism, in 1989.[67] The purpose of this Act is (s. 3):[84]

- encouraging recognition and acceptance of multiculturalism as an inherent feature of a pluralistic society;

- establishing a climate for harmonious relations among people of diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds without sacrificing their distinctive cultural and ethnic identities;

- encouraging the continuation of a multicultural society as a mosaic of different ethnic groups and cultures

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island introduced their legislation on multiculturalism, the Provincial Multicultural Policy, in 1988.[67] This policies objectives were (s. 4):[85]

- serve to indicate that the province embraces the multicultural reality of Canadian society and acknowledges that Prince Edward Island has a distinctive multicultural heritage

- acknowledge the intrinsic worth and continuing contribution of al Prince Edward Islanders regardless of race, religion ethnicity, linguistic origin or length of residency.

- serve as an affirmation of Human Rights for all Prince Edward Islanders and as a complement to the equality of rights guaranteed in the P.E.I. Human Rights Act and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

- encourage specific legislative, political and social commitments to multiculturalism in Prince Edward Island

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador first legislated their Policy on Multiculturalism in 2008.[67] Some of the policies are to:[86]

- ensure that relevant policies and procedures of provincial programs and practices reflect, and consider the changing needs of all cultural groups;

- lead in developing, sustaining and enhancing programs and services based on equality for all, notwithstanding racial, religious, ethnic, national and social origin;

- provide government workplaces that are free of discrimination and that promote equality of opportunity for all persons accessing employment positions within the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador;

- support multicultural initiatives by enhancing partnerships with culturally-diverse communities and provincial departments and agencies

Domestic support and global influence

Canadian multiculturalism is looked upon with admiration outside the country, resulting in the Canadian public dismissing most critics of the concept.[2][87][88][89] Multiculturalism is often cited as one of Canada's significant accomplishments and a key distinguishing element of Canadian identity.[2][90][91] Multiculturalism has been emphasized in recent decades. Emma Ambrose and Cas Mudde examining surveys of Western nations report:

Data confirms that Canada has fostered a much more accepting society for immigrants and their culture than other Western countries. For example, Canadians are the most likely to agree with the statement that immigrants make their country a better place to live and that immigrants are good for the economy. They are also the least likely to say that there are too many immigrants in their country, that immigration has placed too much pressure on public services, and that immigrants have made it more difficult for natives to find a job.[92]

Ambrose and Mudde conclude that: "Canada's unique multiculturalism policy... is based on a combination of selective immigration, comprehensive integration, and strong state repression of dissent on these policies".[92] This unique blend of policies has led to a relatively low level of opposition to multiculturalism.[92][93]

Canadian supporters of multiculturalism promote the idea because they believe that immigrants help society grow culturally, economically and politically.[94][95] Supporters declare that multiculturalism policies help in bringing together immigrants and minorities in the country and pushes them towards being part of the Canadian society as a whole.[95][96][97] Supporters also argue that cultural appreciation of ethnic and religious diversity promotes a greater willingness to tolerate political differences.[90]

Andrew Griffith argues that, "89 percent of Canadians believe that foreign-born Canadians are just as likely to be good citizens as those born in Canada....But Canadians clearly view multiculturalism in an integrative sense, with an expectation that new arrivals will adopt Canadian values and attitudes." Griffith adds that, "There are virtually no differences between Canadian-born and foreign-born with respect to agreement to abide by Canadian values (70 and 68 percent, respectively)."[98] Richard Gwyn has suggested that "tolerance" has replaced "loyalty" as the touchstone of Canadian identity.[90]

Aga Khan, the 49th Imam of the Ismaili Muslims, described Canada as:[87][99] "the most successful pluralist society on the face of our globe, without any doubt in my mind.... That is something unique to Canada. It is an amazing global human asset. Aga Khan explained that the experience of Canadian governance – its commitment to pluralism and its support for the rich multicultural diversity of its peoples – is something that must be shared and would be of benefit to societies in other parts of the world.[100] With this in mind, in 2006 the Global Centre for Pluralism was established in partnership with the Government of Canada.[101]

A 2008 survey by the Association for Canadian Studies of 600 immigrants showed that 81% agreed with the statement; “The rest of the world could learn from Canada's multicultural policy”.[102] The Economist ran a cover story in 2016 praising Canada as the most successful multicultural society in the West.[103] The Economist argued that Canada's multiculturalism was a source of strength that united the diverse population and by attracting immigrants from around the world was also an engine of economic growth as well.[103]

Criticisms

Critics of multiculturalism in Canada often debate whether the multicultural ideal of benignly co-existing cultures that interrelate and influence one another, and yet remain distinct, is sustainable, paradoxical or even desirable.[104][105][106] In the introduction to an article which presents research showing that "the multiculturalism policy plays a positive role" in "the process of immigrant and minority integration," Citizenship and immigration Canada sums up the critics' position by stating:[107]

Critics argue that multiculturalism promotes ghettoization and balkanization, encouraging members of ethnic groups to look inward, and emphasizing the differences between groups rather than their shared rights or identities as Canadian citizens.

Canadian Neil Bissoondath in his book Selling Illusions: The Cult of Multiculturalism in Canada, argues that official multiculturalism limits the freedom of minority members, by confining them to cultural and geographic ethnic enclaves ("social ghettos").[108] He also argues that cultures are very complex, and must be transmitted through close family and kin relations.[109] To him, the government view of cultures as being about festivals and cuisine is a crude oversimplification that leads to easy stereotyping.[109]

Canadian Daniel Stoffman's book Who Gets In questions the policy of Canadian multiculturalism. Stoffman points out that many cultural practices (outlawed in Canada), such as allowing dog meat to be served in restaurants and street cockfighting, are simply incompatible with Canadian and Western culture.[110] He also raises concern about the number of recent older immigrants who are not being linguistically integrated into Canada (i.e., not learning either English or French).[110] He stresses that multiculturalism works better in theory than in practice and Canadians need to be far more assertive about valuing the "national identity of English-speaking Canada".[110]

Professor Joseph Garcea, the Department Head of Political Studies at the University of Saskatchewan, explores the validity of attacks on multiculturalism because it supposedly segregates the peoples of Canada. He argues that multiculturalism hurts the Canadian, Québécois, and indigenous cultures, identity, and nationalism projects. Furthermore, he argues, it perpetuates conflicts between and within groups.[111]

When Jason Kenney, was made parliamentary secretary and secretary of state for multiculturalism in 2008, then Prime Minister Stephen Harper raised concerns to Kenney that "multiculturalism cannot lead to the ghettoization of immigrants."[112] In 2003 when the Progressive Conservative party created a research dossier of remarks by Harper; they pointed out that a statement in 2001 where accused immigrants and recent migrants from eastern Canada in ridings that are "west of Winnipeg the ridings the Liberals" of living in a ghetto and do not integrate into Western Canada.[113][114]

A 2017 Poll found 37% of Canadians said too many refugees were coming to Canada, up from 30% in 2016. The 2017 poll also asked respondents about their comfort levels around people of different races and religions, a question that was also asked in 2005-06. This year, 89% said they were comfortable around people of a different race, down from 94% in 2005-2006. [115]

Quebec society

Despite an official national bilingualism policy, many commentators from Quebec believe multiculturalism threatens to reduce them to just another ethnic group.[116][117] Quebec's policy seeks to promote interculturalism, welcoming people of all origins while insisting that they integrate into Quebec's majority French-speaking society.[118] In 2008, a Consultation Commission on Accommodation Practices Related to Cultural Differences, headed by sociologist Gerard Bouchard and philosopher Charles Taylor, recognized that Quebec is a de facto pluralist society, but that the Canadian multiculturalism model "does not appear well suited to conditions in Quebec".[119]

See also

References

- Kobayashi, Audrey (1983), "Multiculturalism: Representing a Canadian Institution", in Duncan, James S; Duncan, Ley (eds.), Place/culture/representation, Routledge, pp. 205–206, ISBN 978-0-415-09451-1

- Azeezat Johnson; Remi Joseph-Salisbury; Beth Kamunge (2018). The Fire Now: Anti-Racist Scholarship in Times of Explicit Racial Violence. Zed Books. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-78699-382-3.

- Wayland, Shara (1997), Immigration, Multiculturalism and National Identity in Canada (PDF), University of Toronto (Department of Political Science), archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011, retrieved September 12, 2010

- Ronald L. Jackson, II (June 29, 2010). Encyclopedia of Identity. SAGE. p. 480. ISBN 978-1-4129-5153-1.

- "Current Publications: Social affairs and population: Canadian Multiculturalism". lop.parl.ca. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- Michael Dewing (2013). Canadian Multiculturalism (PDF). Publication No. 2009-20-E Library of Parliament. Legal and Social Affairs Division Parliamentary Information and Research Service. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- Bernardo Berdichewsky (2007). Latin Americans Integration Into Canadian Society onB C. The Canadian Association for Latin American and Caribbean Studies. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-9784152-0-4.

- Troper, H. (1980). Multiculturalism Archived March 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Multicultural Canada. Retrieved March 28, 2012

- Charmaine Nelson; Camille Antoinette Nelson (2004). Racism, Eh?: a critical inter-disciplinary anthology of race and racism in Canada. Captus Press. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-55322-061-9.

- Jill Vickers; Annette Isaac (2012). The Politics of Race: Canada, the United States, and Australia. University of Toronto Press - Carleton University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4426-1131-3.

- Anne-Marie Mooney Cotter (2011). Culture clash: an international legal perspective on ethnic discrimination. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4094-1936-5.

- Guy M. Robinson (1991). A Social geography of Canada. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-55002-092-2.

- Derek Hayes (2008). Canada: an illustrated history. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-55365-259-5.

- Richard S. Levy (2005). Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution. ABC-CLIO. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-85109-439-4.

- Matthew J. Gibney; Randall Hansen (2005). Immigration and asylum: from 1900 to the present. ABC-CLIO. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-57607-796-2.

- Grace-Edward Galabuzi (2006). Canada's Economic Apartheid: The Social Exclusion of Racialized Groups in the New Century. Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-55130-265-2.

- Yasmeen Abu-Laban; Christina Gabriel (2002). Selling diversity: immigration, multiculturalism, employment equity, and globalization. University of Toronto Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-1-55111-398-2.

- Jessie Carney Smith (2010). Encyclopedia of African American Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-313-35796-1.

- Richard J. F. Day (2000). Multiculturalism and the history of Canadian diversity. University of Toronto Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-8020-8075-2.

- W. Peter Ward (1990). White Canada forever: popular attitudes and public policy toward Orientals in British Columbia. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7735-0824-8.

- Rand Dyck (March 2011). Canadian Politics. Cengage Learning. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-17-650343-7.

- Joan Church; Christian Schulze; Hennie Strydom (2007). Human rights from a comparative and international law perspective. Unisa Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-86888-361-5.

- Christopher MacLennan (2004). Toward the Charter: Canadians and the Demand for a National Bill of Rights, 1929–1960. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-7735-2536-8.

- J. M. Bumsted (2003). Canada's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-57607-672-9.

- Matthew J. Gibney; Randall Hansen (2005). Immigration and Asylum: From 1900 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-57607-796-2.

- Edward Ksenych; David Liu (2001). Conflict, order and action: readings in sociology. Canadian Scholars' Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-1-55130-192-1.

- "Living in Canada: founded on cultural diversity". Akcanada. 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "2006 Census release topics". Statistics Canada. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- Dolin, Benjamin; Young, Margaret (October 31, 2004), Canada's Immigration Program (PDF), Library of Parliament (Law and Government Division), retrieved November 29, 2006

- "Canada's Generous Program for Refugee Resettlement Is Undermined by Human Smugglers Who Abuse Canada's Immigration System". Public Safety Canada. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- "Canada – Permanent residents by gender and category, 1984 to 2008". Facts and figures 2008 – Immigration overview: Permanent and temporary residents. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2009. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- Rodger W. Bybee; Barry McCrae (2009). Pisa Science 2006: Implications for Science Teachers and Teaching. NSTA Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-933531-31-1.

- James Hollifield; Philip Martin; Pia Orrenius (2014). Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, Third Edition. Stanford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8047-8627-0.

- Elspeth Cameron (2004). Multiculturalism and Immigration in Canada: An Introductory Reader. Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-55130-249-2.

- "Is the current model of immigration the best one for Canada?", The Globe and Mail, Canada, December 12, 2005, retrieved August 16, 2006

- Manning, 1992. Pviii.

- Grace-Edward Galabuzi (2006). Canada's economic apartheid: the social exclusion of racialized groups in the new century. Canadian Scholars' Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-55130-265-2.

- Zucchi, J (2007). A history of ethnic enclaves in Canada (PDF). Canadian Historical Association. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-0-88798-266-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 1, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- Christian Dufour; Institute for Research on Public Policy (1990). A Canadian Challenge. IRPP. ISBN 978-0-88982-105-7.

- François Vaillancourt; Olivier Coche. Official Language Policies at the Federal Level in Canada:costs and Benefits in 2006. The Fraser Institute. p. 11. GGKEY:B3Y7U7SKGUD.

- Daniel Francis (1997). National Dreams: Myth, Memory, and Canadian History. arsenal pulp press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-55152-043-8.

- Julia Straub (2016). Handbook of Transatlantic North American Studies. De Gruyter. pp. 516–. ISBN 978-3-11-037673-9.

- Veronica Benet-Martinez; Ying-Yi Hong (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Multicultural Identity. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-979675-5.

- Miriam Verena Richter (2011). Creating the National Mosaic: Multiculturalism in Canadian Children’s Literature from 1950 to 1994. Rodopi. p. 36. ISBN 94-012-0050-5.

- Norman Hillmer; Adam Chapnick (2007). Canadas of the mind: the making and unmaking of Canadian nationalisms in the twentieth century. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-7735-3273-1.

- Saunders, Doug (June 27, 2009), "Canada's mistaken identity", The Globe and Mail, Canada, retrieved June 28, 2009

- Godbout, Adelard (April 1943), "Canada: Unity in Diversity", Foreign Affairs, 21 (3): 452–461, JSTOR 20029241

- Roxanne, Lalonde (April 1994), "Edited extract from M.A. thesis", Unity in Diversity: Acceptance and Integration in an Era of Intolerance and Fragmentation, Ottawa, Ontario: Department of Geography, Carleton University, retrieved January 9, 2014

- "Gwich'in Tribal Council Annual Report 2012 - 2013: Unity through diversity" (PDF), Gwich’in Tribal Council, 2013, retrieved September 5, 2014

- Desmond Morton (2006). A short history of Canada. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7710-6480-7.

- Nelson Wiseman (2007). In search of Canadian political culture. UBC Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-7748-1388-4.

- Martin N. Marger (2008). Race and Ethnic Relations: American and Global Perspectives. Cengage Learning. pp. 458–. ISBN 978-0-495-50436-8.

- Irvin Studin (2009). What Is a Canadian?: Forty-Three Thought-Provoking Responses. McClelland & Stewart. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-55199-283-9.

- Miriam Verena Richter (2011). Creating the National Mosaic: Multiculturalism in Canadian Children's Literature from 1950 To 1994. Rodopi. p. 36. ISBN 978-90-420-3351-1.

- Miriam Verena Richter (2011). Creating the National Mosaic: Multiculturalism in Canadian Children¿s Literature from 1950 To 1994. Rodopi. p. 37. ISBN 978-90-420-3351-1.

- James Laxer; Robert M. Laxer (1977). The Liberal Idea of Canada: Pierre Trudeau and the Question of Canada's Survival. James Lorimer & Company. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-88862-124-5.

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau, as cited in The Essential Trudeau, ed. Ron Graham. (pp.16 – 20). "The Just Society" (PDF). Government of Manitoba. Retrieved December 6, 2015.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jonathan L. Black-Branch; Canadian Education Association (1995). Making Sense of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Canadian Education Association. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-920315-78-1.

- David Bennett (1998). Multicultural states: rethinking difference and identity. Psychology Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-415-12159-0.

- Stephen M. Caliendo; Charlton D. McIlwain (2011). The Routledge companion to race and ethnicity. Taylor & Francis. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-415-77706-3.

- William H. Mobley; Ming Li; Ying Wang (2012). Advances in Global Leadership. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-78052-003-2.

- "Proclamation Declaring June 27 of each year as "Canadian Multiculturalism Day"". Deputy Registrar General of Canada (Canadian Heritage). 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- Michael J. Perry (2006). Toward a Theory of Human Rights: Religion, Law, Courts. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-139-46082-8.

- "Canadian Multiculturalism Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. 24 (4th Supp.)". Department of Justice. 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- Robin Mansell; Marc Raboy (2011). The Handbook of Global Media and Communication Policy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 149–151. ISBN 978-1-4443-9541-9.

- Marc Raboy; William J. McIver; Jeremy Shtern (2010). Media divides: communication rights and the right to communicate in Canada. UBC Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7748-1774-5.

- "Canadian Multiculturalism" (PDF). Staff of the Parliamentary Information and Research Service (PIRS). 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "Multicultiralism Act". Queen's Printer. 1993. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "Protected Area and Grounds under the Alberta Human Rights Act" (PDF). Human Rights Commission. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 8, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "CanLII - Alberta Human Rights Act, RSA 2000, c A-25.5". Canlii.ca. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- "The Multiculturalism Act" (PDF). Statutes of Saskatchewan. 1997. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- Jene M. Porter (2009). Perspectives of Saskatchewan. Univ. of Manitoba Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-88755-353-0.

- "The Manitoba Multiculturalism Act". Manitoba. 1992. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "The Ministry of Citizen and Culture Act". e-Laws. 1990. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- Martyn Barrett (2013). Interculturalism and multiculturalism: similarities and differences. Council of Europe. p. 53. ISBN 978-92-871-7813-8.

- Peter Balint; Sophie Guérard de Latour (2013). Liberal Multiculturalism and the Fair Terms of Integration. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-137-32041-4.

- Lead Researcher - Elke Winter, Research Assistant - Adina Madularea (2014). "Multiculturalism Research Synthesis 2009 - 2013" (PDF). Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- Ramón Máiz; Ferrán Requejo (2004). Democracy, Nationalism and Multiculturalism. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-134-27696-7.

- Alain G. Gagnon; Raffaele Iacovino (2006). Federalism, Citizenship and Quebec. University of Toronto Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-1-4426-9147-6.

- "Policy Networks and Policy Change: Explaining Immigrant Integration Policy Evolution in Quebec" (PDF). Junichiro Koji. 2009. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ICI.Radio-Canada.ca, Zone Politique-. "Un logo tout bleu pour le virage nationaliste de la CAQ". Radio-Canada.ca (in French). Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- Shingler, Benjamin (October 1, 2018). "Here are the priorities of Quebec's new CAQ government". CBC News. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- "New Brunswick Multicultural Policy". The Government of New Brunswick. 2012. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "Multiculturalism Act". Office of the Legislative Counsel. 1989. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "Provincial Multicultural Policy" (PDF). Government of P.E.I. 1989. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- "Multiculturalism Policy" (PDF). Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- Linda A. White; Richard Simeon (2009). The Comparative Turn in Canadian Political Science. UBC Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7748-1428-7.

- Stephen J Tierney (2011). Multiculturalism and the Canadian Constitution. UBC Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7748-4007-1.

- Taub, Amanda (2017). "Canada's Secret to Resisting the West's Populist Wave". New York Times.

- Richard J. Gwyn (2008). John A: The Man Who Made Us. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-679-31476-9.

- Jack Jedwab (2016). Multiculturalism Question: Debating Identity in 21st Century Canada. MQUP. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-55339-423-5.

- Emma Ambrosea & Cas Muddea (2015). "Canadian Multiculturalism and the Absence of the Far Right". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 21 Issue 2 (2): 213–236. doi:10.1080/13537113.2015.1032033.

- "A literature review of Public Opinion Research on Canadian attitudes towards multiculturalism and immigration, 2006-2009". Government of Canada. 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- James Hollifield; Philip L. Martin; Pia Orrenius (2014). Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, Third Edition. Stanford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8047-8735-2.

- "The current state of multiculturalism in Canada and research themes on Canadian multiculturalism". Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- Pierre Boyer; Linda Cardinal; David John Headon (2004). From Subjects to Citizens: A Hundred Years of Citizenship in Australia and Canada. University of Ottawa Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-7766-0553-1.

- Elke Murdock (2016). Multiculturalism, Identity and Difference: Experiences of Culture Contact. Springer. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-137-59679-6.

- Andrew Griffith (2015). Multiculturalism In Canada: Evidence and Anecdote. p. 50.

- Stackhouse, John; Martin, Patrick (February 2, 2002), "Canada: 'A model for the world'", The Globe and Mail, Canada, p. F3, retrieved June 29, 2009,

Canada is today the most successful pluralist society on the face of our globe, without any doubt in my mind. . . . That is something unique to Canada. It is an amazing global human asset

- Prince Karim Aga Khan IV (May 19, 2004), Address at the Leadership and Diversity Conference, Gatineau, Canada, archived from the original on March 3, 2016, retrieved March 21, 2007

- Courtney Bender; Pamela E. Klassen (2010). After Pluralism: Reimagining Religious Engagement. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15233-4.

- Jack Jedwab (2008). "Immigrants believe the rest of the World could learn from Canada's Multicultural Policy" (PDF). The Association for Canadian Studies. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- "The last liberals Why Canada is still at ease with openness". The Economist. October 29, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- John Nagle (2009). Multiculturalism's double bind: creating inclusivity, cosmopolitanism and difference. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7546-7607-2.

- Farhang Rajaee (2000). Globalization on trial: the human condition and the information civilization. IDRC. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-88936-909-2.

- Leonie Sandercock; Giovanni Attili; Val Cavers; Paula Carr (2009). Where strangers become neighbours: integrating immigrants in Vancouver, British Columbia. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4020-9034-9.

- "Citizenship and Immigration Canada". The New Evidence on Multiculturalism and Integration. The current state of multiculturalism in Canada and research themes on Canadian multiculturalism. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Giuliana B. Prato (2009). Beyond multiculturalism: views from anthropology. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7546-7173-2.

- Lalaie Ameeriar; Stanford University. Dept. of Anthropology (2008). Downwardly global: multicultural bodies and gendered labor migrations from Karachi to Toronto. Stanford University. pp. 21–22.

- Phil Ryan (2010). Multicultiphobia. University of Toronto Press. pp. 103–106. ISBN 978-1-4426-1068-2.

- Garcea, Joseph (2008). Postulations on the Fragmentary Effects of Multiculturalism in Canada. 40 Issue 1, pp 141–160. Canadian Ethnic Studies. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- "The inside story of Jason Kenney's campaign to win over ethnic votes - Macleans.ca". www.macleans.ca. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- "A selection of controversial Harper quotes compiled by the Tories". Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- "The devil in Stephen Harper". NOW Magazine. June 3, 2004. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- "Canadian attitudes towards immigration hardening, poll suggests - The Star". thestar.com.

- Christian Lammert; Katja Sarkowsky (2009). Negotiating Diversity in Canada and Europe. VS Verlag. p. 177. ISBN 978-3-531-16892-0.

- Danic Parenteau (2010). "Critique du multiculturalisme canadien. Une synthèse récapitulative" (PDF). L'Action Nationale (Mars): 36–46.

- Assaad E. Azzi; Xenia Chryssochoou; Bert Klandermans; Bernd Simon (2011). Identity and Participation in Culturally Diverse Societies: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. John Wiley & Sons. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-4443-5181-1.

- Bouchard, Gérard; Taylor, Charles (2008), Building the Future: A Time for Reconciliation (PDF), Québec, Canada: Commission de consultation sur les pratiques d'accommodement reliées aux différences culturelles, archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2012, retrieved October 20, 2011

Further reading

- Kymlicka, Will (2010). The Current State of Multiculturalism in Canada (PDF). Department of Citizenship and Immigration. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. ISBN 978-1-100-14648-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- Banting, Keith; Kymlicka, Will (2010). Canadian Multiculturalism: Global Anxieties and Local Debates (PDF). 23 Issue 1. British Journal of Canadian Studies.

- Garcea, Joseph (2008). "Postulations on the Fragmentary Effects of Multiculturalism in Canada". Canadian Ethnic Studies. 40 (1): 141–160. doi:10.1353/ces.0.0059.

- Ninette Kelley; Michael J. Trebilcock (2010). The making of the mosaic: a history of Canadian immigration policy. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- Janice Gross Stein (2007). Uneasy partners: multiculturalism and rights in Canada. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-012-5.

- Stephen Tierney (2007). Multiculturalism and the Canadian Constitution. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1445-4.

- Kristin R. Good (2009). Municipalities and Multiculturalism: The Politics of Immigration in Toronto and Vancouver. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-0993-8.

- Richard J. F. Day (2000). Multiculturalism and the history of Canadian diversity. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8075-2.

- Eve Haque (2012). Multiculturalism Within a Bilingual Framework: Language, Race, and Belonging in Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-6089-2.

- Yasmeen, Abu-Laban; Stasiulis, Daiva (2000). "Ethnic Pluralism under Siege: Popular and Partisan Opposition to Multiculturalism". Canadian Public Policy. 18 (4): 365–386. JSTOR 3551654.

- Pivato, Joseph. Editor (1996) Literary Theory and Ethnic Minority Writing, Special Issue Canadian Ethnic Studies XXVIII, 3 (1996).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Multiculturalism in Canada. |

- Multiculturalism in Canada debated – CBC video archives (Sep 14, 2004 – 42:35 min)

- Multicultural Canada – Government of Canada

- Multiculturalism – Citizenship and Immigration Canada

- Multiculturalism & Diversity – Association for Canadian Studies