Dog meat

Dog meat is the flesh and other edible parts derived from dogs. Historically, human consumption of dog meat has been recorded in many parts of the world.[2] In the 21st century, dog meat is consumed in China,[3] South Korea,[4] Vietnam,[5] Nigeria,[6] and Switzerland,[7] and it is eaten or is legal to be eaten in other countries throughout the world. Some cultures view the consumption of dog meat as part of their traditional, ritualistic, or day-to-day cuisine, and other cultures consider consumption of dog meat a taboo, even where it had been consumed in the past. Opinions also vary drastically across different regions within different countries.[8][9] It was estimated in 2014 that worldwide, 25 million dogs are eaten each year by humans.[10]

Various cuts of dog meat | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,096 kJ (262 kcal) |

0.1 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 0 g |

20.2 g | |

19 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 3.6 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 10% 0.12 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 15% 0.18 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 13% 1.9 mg |

| Vitamin C | 4% 3 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 8 mg |

| Iron | 22% 2.8 mg |

| Phosphorus | 24% 168 mg |

| Potassium | 6% 270 mg |

| Sodium | 5% 72 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 60.1 g |

| Cholesterol | 44.4 mg |

| Ash | 0.8 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: Yong-Geun Ann (1999)[1] | |

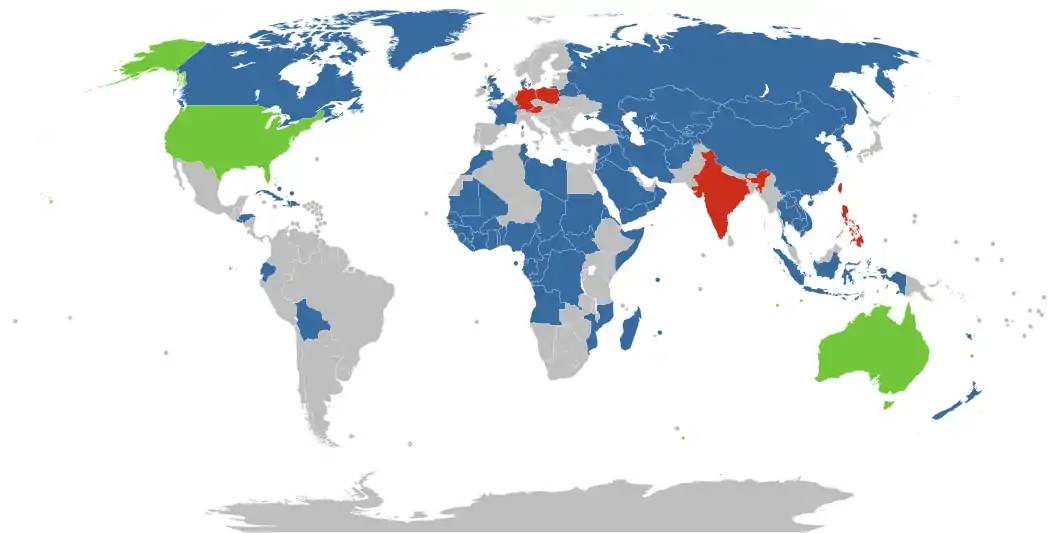

| | Dog killing is legal. | | Dog killing is partially illegal.1 |

| | Dog killing is illegal. | | Unknown |

Historical practices

Aztecs

In the Aztec Empire, Mexican hairless dogs were bred for, among other purposes,[11] their meat. Hernán Cortés reported when he arrived in Tenochtitlan in 1519, "small gelded dogs which they breed for eating" were among the goods sold in the city markets.[12] These dogs, Xoloitzcuintles, were often depicted in pre-Columbian Mexican pottery. The breed was almost extinct in the 1940s, but the British military attaché in Mexico City, Norman Wright, developed a thriving breed from some of the dogs he found in remote villages.[13]

Native North Americans

The traditional culture surrounding the consumption of dog meat varied from tribe to tribe among the original inhabitants of North America, with some tribes relishing it as a delicacy, and others (such as the Comanche) treating it as a forbidden food.[14] Native peoples of the Great Plains, such as the Sioux and Cheyenne, consumed it, but there was a concurrent religious taboo against the meat of wild canines.[15]

The Kickapoo people include puppy meat in many of their traditional festivals.[16] This practice has been well documented in the Works Progress Administration "Indian Pioneer History Project for Oklahoma".[17][18]

On 20 December 2018, the federal Dog and Cat Meat Trade Prohibition Act was signed into law as part of the 2018 Farm Bill. It bans slaughtering dogs and cats for food in the United States, with exceptions for Native American rituals.[19]

Europe

Brittonic and Irish texts which date from the early Christian period suggest that dog meat was sometimes consumed but possibly in ritual contexts such as Druidic ritual trance. Sacrificial dog bones are often recovered from archaeological sites;[20] They were typically treated differently, as were horses, from other food animals.[21] One of Ireland's mythological heroes, Cuchulainn, had two geasa, or vows, one of which was to avoid the meat of dogs. The breaking of his geasa led to his death in the Irish mythology.

Dog meat has been consumed in the past by the Gauls. The evidence of dog consumption was found at Gaulish archaeological sites, where butchered dog bones were discovered.[22]

Polynesia

Dogs were historically eaten in Tahiti and other islands of Polynesia, including Hawaii[23][24] at the time of first European contact. James Cook, when first visiting Tahiti in 1769, recorded in his journal, "few were there of us but what allow'd that a South Sea Dog was next to an English Lamb, one thing in their favour is that they live entirely upon Vegetables".[25] Calwin Schwabe reported in 1979 that dog was widely eaten in Hawaii and considered to be of higher quality than pork or chicken. When Hawaiians first encountered early British and American explorers, they were at a loss to explain the visitors' attitudes about dog meat. The Hawaiians raised both dogs and pigs as pets and for food. They could not understand why their British and American visitors only found the pig suitable for consumption.[2] This practice seems to have died out, along with the native Hawaiian breed of dog, the unique Hawaiian Poi Dog, which was primarily used for this purpose.[26]

Although Hawaii has outlawed commercial sales of dog meat, until the federal Dog and Cat Meat Trade Prohibition Act it was legal to slaughter an animal classified as a pet if it was "bred for human consumption" and done in a "humane" manner. This allowed dog meat trade to continue, mostly using stray, lost, or stolen dogs.[27][28]

Religious dietary laws

According to Kashrut, Jewish dietary law, it is forbidden to consume the flesh of terrestrial predators who do not chew their cud and have cloven hooves, which includes dogs. In Islamic dietary laws, the consumption of the flesh of a dog, or any carnivorous animal, or any animal bearing fangs, claws, fingers or reptilian scales, is prohibited, except in Maliki jurisprudence.[29]

Dogs as survival food

Wars and famines

In most European countries, the consumption of dog meat is taboo. Exceptions occurred in times of scarcity, such as sieges or famines.

In Germany, dog meat has been eaten in every major crisis since at least the time of Frederick the Great, and was commonly referred to as "blockade mutton".[8]

During the Siege of Paris (1870–1871), food shortages caused by the German blockade of the city caused the citizens of Paris to turn to alternative sources for food, including dog meat. Dog meat was also reported as being sold by some butchers in Paris in 1910.[30][31]

In the early 20th century, high meat prices led to widespread consumption of horse and dog meat in Germany.[32][33][34]

In the early 20th century in United States, dog meat was consumed during times of meat shortage.[35]

A few meat shops sold dog meat during the German occupation of Belgium in World War I, when food was extremely scarce.[36]

In the latter part of World War I, dog meat was being eaten in Saxony by the poorer classes because of famine conditions.[37]

In Germany, the consumption of dog meat continued in the 1920s.[38][39] In 1937, a meat inspection law targeted against trichinella was introduced for pigs, dogs, boars, foxes, badgers, and other carnivores.[40]

During severe meat shortages coinciding with the German occupation from 1940 to 1945, sausages found to have been made of dog meat were confiscated by Nazi authorities in the Netherlands.[41]

Expeditions and emergencies

Travelers sometimes have to eat their accompanying dogs to survive when stranded without other food. For example, Benedict Allen ate his dog when lost in Brazilian rainforest.[42] A case in Canada was reported in 2013.[43]

Lewis and Clark

During Lewis and Clark expedition (1803–1806), Meriwether Lewis and the other members of the Corps of Discovery consumed dog meat, either from their own animals or supplied by Native American tribes, including the Paiutes and Wah-clel-lah Indians, a branch of the Watlatas,[44] the Clatsop,[45] the Teton Sioux (Lakota),[46] the Nez Perce Indians (who did not eat dog themselves[47]),[48] and the Hidatsas.[49] Lewis and the members of the expedition ate dog meat, except William Clark, who reportedly could not bring himself to eat dogs.[50][51][52]

Polar exploration

British explorer Ernest Shackleton and his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition became trapped, and ultimately killed their sled dogs for food.

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen's party famously planned to eat their sled dogs, as well as to feed weaker dogs to other dogs, during their expedition to the South Pole. This allowed the party to carry less food, thus lightening the load, and ultimately helped Amundsen to win his race to the South Pole against Robert Scott's expedition, which used ponies.[53] When comparing sled dogs to ponies as draught animals, Amundsen noted:

There is the obvious advantage that dog can be fed on dog. One can reduce one's pack little by little, slaughtering the feebler ones and feeding the chosen with them. In this way they get fresh meat. Our dogs lived on dog's flesh and pemmican the whole way, and this enabled them to do splendid work. And if we ourselves wanted a piece of fresh meat we could cut off a delicate little fillet; it tasted to us as good as the best beef. The dogs do not object at all; as long as they get their share they do not mind what part of their comrade's carcass it comes from. All that was left after one of these canine meals was the teeth of the victim – and if it had been a really hard day, these also disappeared.[54]

Douglas Mawson and Xavier Mertz were part of the Far Eastern Party, a three-man sledging team with Lieutenant B. E. S. Ninnis, to survey King George V Land, Antarctica. On 14 December 1912 Ninnis fell through a snow-covered crevasse along with most of the party's rations, and was never seen again. Mawson and Mertz turned back immediately. They had one and a half weeks' food for themselves and nothing at all for the dogs. Their meagre provisions forced them to eat their remaining sled dogs on their 315-mile (507 km) return journey. Their meat was tough, stringy and without a vestige of fat. Each animal yielded very little, and the major part was fed to the surviving dogs, which ate the meat, skin and bones until nothing remained. The men also ate the dog's brains and livers. Unfortunately eating the liver of sled dogs produces the condition hypervitaminosis A because canines have a much higher tolerance for vitamin A than humans do. Mertz suffered a quick deterioration. He developed stomach pains and became incapacitated and incoherent. On 7 January 1913, Mertz died. Mawson continued alone, eventually making it back to camp alive.[9]

Modern practices

Democratic Republic of the Congo

In 2011 it was reported that, due to high prices on other types of meat, the consumption of dog meat is common despite a longstanding taboo.[56]

Ghana

The Tallensi, the Akyims, the Kokis, and the Yaakuma, one of many cultures of Ghana, consider dog meat a delicacy. The Mamprusi generally avoid dog meat, and it is eaten in a "courtship stew" provided by a king to his royal lineage. Two Tribes in Ghana, Frafra and Dagaaba are particularly known to be "tribal playmates" and consumption of dog meat is the common bond between the two tribes. Every year around September, games are organised between these two tribes and the Dog Head is the trophy at stake for the winning tribe.[57]

It was reported in 2017 that increasing demand for dog meat (due to the belief it gives more energy) has led politician Anthony Karbo to propose dog meat factories in three northern regions of Ghana.[58][59]

Nigeria

Dogs are eaten by various groups in some states of Nigeria, including Ondo State, Akwa Ibom, Cross River, Plateau, Kalaba, Taraba and Gombe of Nigeria.[57][60] They are believed to have medicinal powers.[6][61]

In late 2014, the fear of contracting the Ebola virus disease from bushmeat led at least one major Nigerian newspaper to imply that eating dog meat was a healthy alternative.[62] That paper documented a thriving trade in dog meat and slow sales of even well smoked bushmeat.

Cambodia

Animal welfare NGO Four Paws estimates that 2–3 million dogs are slaughtered annually for their meat in Cambodia. Methods of slaughtering the dog can range from strangulation, drowning, stabbing, or clubbing the head.[63] According to a market research study in 2019 on the dog meat trade in Cambodia, overall a total of 53.6% of respondents indicated that they have eaten dog meat at some time in their lives (72.4% of males and 34.8% of females).[64]

Mainland China

Estimates for total dog killings in China range from 10 to 20 million dogs annually, for purposes of human consumption.[65] However, estimates such as these are not official and are derived from extrapolating industry reports on meat tonnage to an estimate of dogs killed.[66] Consuming dog meat is legal in mainland China, and the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture has never issued quarantine procedures for slaughtering dogs.[67][68] Selling dog meat as food is against the Food Safety Law of the People's Republic of China. According to the Animal Epidemic Prevention Law of the People's Republic of China (2013 Amendment), dogs need to be vaccinated. Dogs for eating are not vaccinated, so they are illegal to transport or to sell.[69]

The eating of dog meat in China dates back thousands of years. Dog meat (Chinese: 狗肉; pinyin: gǒu ròu) has been a source of food in some areas from around 500 BC and possibly even earlier. It has been suggested that wolves in southern China may have been domesticated as a source of meat.[70] Mencius, the philosopher, talked about dog meat as being an edible, dietary meat.[71] It was reported in the early 2000s that the meat was thought to have medicinal properties, and had been popular in northern China during the winter, as it was believed to raise body temperature after consumption and promote warmth.[72][73] Historical records have shown how in times of food scarcities (as in war-time situations), dogs could also be eaten as an emergency food source.[74]

In modern times, the extent of dog consumption in China varies by region. It is most prevalent in Guangdong, Yunnan and Guangxi, as well as the northern provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning.[75] It was reportedly common in 2010 to find dog meat served in restaurants in Southern China, where dogs are reared on farms for consumption.[76] In 2012, Chinese netizens and the Chinese police intercepted trucks transporting caged dogs to be slaughtered in localities such as Chongqing and Kunming.[77]

Since 2009,[78] Yulin, Guangxi, has held an annual festival of eating dog meat (purportedly a celebration of the summer solstice). In 2014, the municipal government published a statement distancing itself from the festival, saying it was not a cultural tradition, but rather a commercial event held by restaurants and the public.[79] The festival in 2011 spanned 10 days, during which 15,000 dogs were consumed.[80] Estimates of the number of dogs eaten in 2015 for the festival ranged from as high as 10,000[69][81] to lower than 1,000 amid growing pressure at home and abroad to end it.[82][83] Festival organizers state that only dogs bred specifically for consumption are used, while objectors say that some of the dogs purchased for slaughter and consumption are strays or stolen pets.[84] Some of the dogs at the festival are alleged to have been burnt or boiled alive[85] or beaten out of the belief that increased adrenaline circulating in the dog's body adds to the flavor of the meat.[69][84] Other reports, however, state that there have been little evidence of those practices since 2015.[83][82]

Prior to the 2014 festival, eight dogs (and their two cages) sold for 1,150 yuan ($185) and six puppies for 1,200 yuan.[86] Prior to the 2015 festival, a protester bought 100 dogs for 7,000 yuan ($1,100; £710).[81] The animal rights NGO Best Volunteer Centre commented that the city had more than 100 slaughterhouses, processing between 30 and 100 dogs a day. The Yulin Centre for Animal Disease Control and Prevention states the city has only eight dog slaughterhouses selling approximately 200 dogs, and this increases to about 2,000 dogs during the Yulin festival.[87] There have been several campaigns to stop the festival, with the first one reportedly having started among locals in China.[83] In 2016, a petition calling for an end to the festival garnered 11 million signatures in the country.[88] More than 3 million people have also signed petitions against it on Weibo (China's equivalent of Twitter).[69] Prior to the 2014 festival, doctors and nurses were ordered not to eat dog meat there, and local restaurants serving dog meat were ordered to cover the word "dog" on their signs and notices.[79] Reports in 2014 and 2016 have also suggested that the majority of Chinese on and offline disapprove of the festival.[89][90][91]

The movement against the consumption of cat and dog meat was given added impetus by the formation of the Chinese Companion Animal Protection Network (CCAPN). Having expanded to more than 40 member societies, CCAPN began organizing protests against eating dog and cat meat in 2006, starting in Guangzhou and continuing in more than ten other cities following a positive response from the public.[92] Before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, officials ordered dog meat to be taken off the menu at its 112 official Olympic restaurants to avoid offending visitors from various nations where the consumption of dog meat is taboo.[93] In 2010, draft legislation was proposed to prohibit the consumption of dog meat.[94] In 2010, the first draft proposal of it was introduced, with the rationale to protect animals from maltreatment. The legislation included a measure to jail people for up to 15 days for eating dog meat,[95] but there were few expectations for it to be enforced.[94]

As of the early 21st century, dog meat consumption is declining or disappearing.[96] In 2014, dog meat sales decreased by a third compared to 2013.[97] It was reported that in 2015, one of the most popular restaurants in Guangzhou serving dog meat was closed after the local government tightened regulations; the restaurant had served dog meat dishes since 1963. Other restaurants that served dog and cat meat in the Yuancun and Panyu districts also stopped serving these dishes in 2015.[98] Close to 9 million Chinese in 2016 also voted online for proposed legislation to end the consumption of dog and cat meat, but the legislation was not taken forward.[82][99]

In April 2020, Shenzhen became the first Chinese city to ban consumption and production of dog and cat meat.[100] This came as part of a wider clampdown on the wildlife trade which was linked to COVID-19 outbreak. Citing examples of Hong Kong and Taiwan, the Shenzhen city government said, "Banning the consumption of dogs and cats and other pets is a common practice in developed countries...This ban also responds to the demand and spirit of human civilization".[101] The city of Zhuhai followed suit in the same month with a similar ban.[102] These decisions were applauded by animal welfare groups such as Humane Society International.[102][103]

In the same month, The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture said it considers dog as 'companion animals', not as livestock, signalling that dog meat consumption may not remain legal for long.[104][105]

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, the Dogs and Cats Ordinance was introduced by the British Hong Kong Government on 6 January 1950.[106] It prohibits the slaughter of any dog or cat for use as food by fine and imprisonment.[107][108] In February 1998, a Hong Konger was sentenced to one month imprisonment and a fine of two thousand HK dollars for hunting street dogs for food.[109] Four local men were sentenced to 30 days imprisonment in December 2006 for having slaughtered two dogs.[110]

Taiwan

In 2001, the Taiwanese government imposed a ban on the sale of dog meat, due to both pressure from domestic animal welfare groups and a desire to improve international perceptions, and there were some protests.[111] In 2007, another law was passed, significantly increasing the fines to sellers of the meat.[112] According to The Daily Meal in 2014, dog meat remained popular in Taiwan despite the laws, especially at smaller towns and villages.[113] Animal rights activists have accused the Taiwanese government of not prosecuting those who continue to slaughter and serve dog meat at restaurants.

In April 2017, Taiwan became the first country in the East Asia to officially ban the consumption of dog and cat meat as well as jail time for those who torture and kill animals. The Animal Protection Act amendments approved by the Legislative Yuan aims to punish the sale, purchase or consumption of dog or cat meat with fines ranging from NT$50,000 to NT$2 million. The amendments also stiffen punishment for those who intentionally harm animals to a maximum two years' imprisonment and fines of NT$200,000 to NT$2 million.[114]

In October 2017, Taiwan's national legislature, known as Legislative Yuan, passed amendments to the country's Animal Protection Act which "bans the sale and consumption of dog and cat meat and of any food products that contain the meat or other parts of these animals."[115]

India

With one of the largest vegetarian populations, consumption of dog meat is very rare in India, seen in a few tribal communities like among certain Tibeto-Burman communities,[116] and in some states of Northeast India, particularly Mizoram,[117] Nagaland,[118] Manipur,[119] Tripura, and Arunachal Pradesh.[120]

In March 2020, the Government of Mizoram passed the Animal Slaughter Bill 2020 which effectively bans dogs from being slaughtered in the state.[121]

In Nagaland, dog lovers had launched a campaign to end Nagaland's dog meat trade.[122] The Government of Nagaland banned the consumption and trading of dog meat in the state on 3 July 2020.[123][124]

Indonesia

Indonesia is predominantly Muslim, a faith which considers dog meat, along with pork, to be haram (ritually unclean).[125] The New York Times has reported that in spite of this, dog meat consumption has been growing in popularity among Muslims and other ethnic groups in the country due to its cheap price and purported health or medicinal benefits.[126]

Although reliable data on the dog meat trade is scarce, various welfare groups estimate that at least 1 million dogs are killed every year to be eaten.[127] On the resort island of Bali alone, between 60,000 and 70,000 dogs are slaughtered and eaten a year, in spite of lingering concerns about the spread of rabies following an outbreak of the disease there a few years ago, according to the Bali Animal Welfare Association.[128] Marc Ching of the Animal Hope and Wellness Foundation claimed in 2017 that the treatment of dogs in Indonesia was the "most sadistic" out of anywhere they were killed for their meat.[129] According to Rappler and The Independent, the slaughter process for dogs in Tomohon, Sulawesi resulted in some of them being blowtorched alive.[130][131]

The consumption of dog meat is often associated with the Minahasa culture of northern Sulawesi,[132] Maluku culture, Toraja culture, various ethnic from East Nusa Tenggara, and the Bataks of northern Sumatra.[133] The code for restaurants or vendors selling dog meat is "RW", an abbreviation for rintek wuuk (Minahasan euphemism means "fine hair") or "B1" abbreviation for biang (Batak language for female dog or "bitch").

Popular Indonesian dog-meat dishes are Minahasan spicy meat dish called rica-rica. Dog meat rica-rica specifically called rica-rica "RW" which stands for Rintek Wuuk in Minahasan dialect, which means "fine hair" as a euphemism referring for fine hair found in roasted dog meat.[125] It is cooked as Patong dish by Toraja people, and as Saksang "B1" (stands for Biang which means "dog" or "bitch" in Batak dialect) by Batak people of North Sumatra. On Java, there are several dishes made from dog meat, such as sengsu (tongseng asu), sate jamu (lit. "medicinal satay"), and kambing balap (lit. "racing goat"). Asu is Javanese for "dog".

Dog consumption in Indonesia gained attention during the 2012 U.S. presidential election when incumbent Barack Obama was pointed out by his opponent to have eaten dog meat served by his Indonesian stepfather Lolo Soetoro when Obama was living in the country.[125] Obama wrote about his experience of eating dog in his book Dreams of My Father,[134] and at the 2012 White House Correspondents' Dinner joked about eating dog.[135][136]

According to Lyn White of Animals Australia, the consumption of dog meat in Bali is not a long-held tradition. She said the meat first came from a Christian ethnic group coming to Bali, where a minority of the immigrants working in the hospitality industry have fuelled the trade.[137]

In June 2017, an investigative report discovered that tourists in Bali are unknowingly eating dog meat sold by street vendors.[138]

Japan

Although the vast majority of Japanese do not eat dog meat, it has been reported that more than 100 outlets in the country have been selling it imported, mainly to Zainichi Korean[139] customers.[140][141] There has been a belief in Japan that certain dogs have special powers in their religion of Shintoism and Buddhism. In 675 AD, Emperor Tenmu decreed a prohibition on its consumption during the 4th through 9th months of the year. According to Meisan Shojiki Ōrai (名産諸色往来) published in 1760, the meat of wild dog was sold along with boar, deer, fox, wolf, bear, raccoon dog, otter, weasel and cat in some regions of Edo.[142]

Korea

Gaegogi (개고기) literally means "dog meat" in Korean. The term itself is often mistaken as the term for Korean soup made from dog meat, which is actually called bosintang (보신탕; 補身湯, Body nourishing soup) (sometimes spelled "bo-shintang").

The consumption of dog meat in Korean culture can be traced through history. Dog bones were excavated in a neolithic settlement in Changnyeong, South Gyeongsang Province. A wall painting in the Goguryeo Tombs complex in South Hwangghae Province, a World Heritage site which dates from the 4th century AD, depicts a slaughtered dog in a storehouse. The Balhae people also enjoyed dog meat, and the modern-day tradition of canine cuisine seems to have come from that era.[143]

People in both Koreas share the belief that consuming dog meat helps stamina during the summer.[144][81]

South Korea

The Humane Society International says that an estimated 2 million[145] or possibly more than 2.5 million dogs are reared on "dog meat farms" in South Korea.[146][147] According to the Korea Animal Rights Advocates (KARA), approximately 780,000 to 1 million dogs are consumed per year in South Korea.[148] The number is lower based on estimates of sales from Moran Market, which occupies 30–40% of dog meat market in the nation.[149] Sales at Moran Market have been declining in the past few years, down to about 20,000 dogs per year in 2017.[150] In recent years dog meat consumption has declined as more people have been adopting dogs as pets. Dog restaurants are also closing down, with reports saying the country's 1,500 dog meat restaurants have almost halved in recent years. Some restaurants have reported declines in consumption of 20–30% per year.[151] A poll conducted by Gallup Korea in 2015 reported that only 20 percent of men in their 20s consumed dog meat, compared to half of those in their 50s and 60s. According to the Korean Animal Rights Advocates (KARA), there are approximately 3,000 dog farms operating across the country,[150] many of which receive dogs from overflow from puppy mills for the pet industry.[152]

Dog meat is often consumed during the winter months and is either roasted or prepared in soups or stews. The most popular of these soups is bosintang and gaejang-guk, a spicy stew meant to balance the body's heat during the summer months. This is thought to ensure good health by balancing one's "qi", the believed vital energy of the body. Dog meat is also believed to increase the body temperature, so people sweat more to keep one cool during the summer (the way of dealing with heat is called Heal heat with heat (이열치열, 以熱治熱, i-yeol-chi-yeol). A 19th-century version of gaejang-guk explains the preparation of the dish by boiling dog meat with vegetables such as green onions and chili pepper powder. Variations of the dish contain chicken and bamboo shoots.[153]

The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety recognizes any edible product other than drugs as food.[154] South Korean Food Sanitary Law (식품위생법) does not include dog meat as a legal food ingredient. In the capital city of Seoul, the sale of dog meat was outlawed by regulation on 21 February 1984, by classifying dog meat as "repugnant food" (혐오식품, 嫌惡食品, hyeom-o sigpum), but the regulation was not rigorously enforced except during the 1988 Seoul Olympics. In 2001, the Mayor of Seoul announced there would be no extra enforcement efforts to control the sale of dog meat during the 2002 FIFA World Cup, which was partially hosted in Seoul. In March 2008, the Seoul Metropolitan Government announced its plan to put forward a policy suggestion to the central government to legally classify slaughter dogs as livestock, reigniting debate on the issue.[155][156][157]

The primary dog breed raised for meat is a non-specific landrace, whose dogs are commonly named as Nureongi (누렁이) or Hwangu (황구).[158][159] Nureongi are not the only type of dog currently slaughtered for their meat in South Korea. In 2015, The Korea Observer reported that many different pet breeds of dog are eaten in South Korea, including labradors, retrievers and cocker spaniels, and that the dogs slaughtered for their meat often include former pets.[160] Some of them have reportedly been stolen from family homes.[161]

There is a large and vocal group of Koreans (consisting of a number of animal welfare groups) who are against the practice of eating dogs.[162] Popular television shows like 'I Love Pet' have documented, in 2011 for instance, the continued illegal sale of dog meat and slaughtering of dogs in suburban areas. The program also televised illegal dog farms and slaughterhouses, showing the unsanitary and horrific conditions of caged dogs, several of which were visibly sick with severe eye infections and malnutrition. Some Koreans do not eat the meat, but feel that it is the right of others to do so. A smaller group wants to popularize the consumption of dog in Korea and the rest of the world.[162] A group of activists attempted to promote and publicize the consumption of dog meat worldwide during the run-up to the 2002 FIFA World Cup, co-hosted by Japan and South Korea, which prompted retaliation from animal rights campaigners and prominent figures such as Brigitte Bardot to denounce the practice.[163] Opponents of dog meat consumption in South Korea are critical of the eating of dog meat, as some dogs are beaten, burnt or hanged to make their meat more tender.[164][165]

The restaurants that sell dog meat, often exclusively, do so at the risk of losing their restaurant licenses. A case of a dog meat wholesaler, charged with selling dog meat, arose in 1997 where an appeals court acquitted the dog meat wholesaler, ruling that dogs were socially accepted as food.[166] According to the National Assembly of South Korea, more than 20,000 restaurants, including the 6,484 registered restaurants, served soups made from dog meat in Korea in 1998.[167][168][169] In 1999 the BBC reported that 8,500 tons of dog meat were consumed annually, with another 93,600 tons used to produce a medicinal tonic called gaesoju (개소주, dog soju ).[169] By 2014 only 329 restaurants served dog meat in Seoul, and the numbers are continuing to decline each year.[170] On 21 November 2018, the South Korean government closed the Taepyeong-dong complex in Seongnam, which served as the country's main dog slaughterhouse.[171][172]

In 2018, Humane Society International stated that South Korea was the only country in Asia where dogs were reported to be routinely and intensively farmed for human consumption.[173]

North Korea

Daily NK reported that in early 2010, the North Korean government included dog meat in its list of one hundred fixed prices, setting a fixed price of 500 won per kilogram.[174]

Malaysia

The consumption of dog meat is legal in Malaysia. The issue was brought to light in 2013 after the Malaysian Independent Animal Rescue group received a report alleging that a restaurant in Kampung Melayu, Subang had dogs caged and tortured before slaughtering them for their meat.[175]

Philippines

The European Society of Dog and Animal Welfare estimates that half a million dogs are slaughtered for food each year in the Philippines.[176]

In the capital city of Manila, Metro Manila Commission Ordinance 82-05 specifically prohibits the killing and selling of dogs for food.[177] More generally, the Philippine Animal Welfare Act 1998[178] prohibits the killing of any animal other than cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, poultry, rabbits, carabaos, horses, deer and crocodiles, with exemptions for religious, cultural, research, public safety and/or animal health reasons. Nevertheless, the consumption of dog meat is not uncommon in the Philippines, reflected in the occasional coverage in Philippine newspapers.[179] Philippine news outlets ABS-CBN and SunStar alleged in 2012 and 2017 that Korean nationals in Baguio had been playing a role in the city's dog meat trade.[180][181]

According to the Animal Welfare Institute, stray dogs have been rounded up off the street for the dog meat trade and shipped to the Benguet province without food or water while steel cans are forced onto their noses and their legs are tied behind their backs. Nearly half the dogs reportedly die before reaching their final destination, with many of them having been people's pets. They are usually then killed via clubbing or having their throats cut, after which their fur is scorched off with a blow-torch and their bodies are dismembered.[182] According to a 2007 book co-authored by Temple Grandin, dogs and other animals in some rural Philippine areas could risk getting beaten before slaughter, out of the belief it would create better meat.[183]

Asocena is a dish primarily consisting of dog meat originating from the Philippines. The province of Benguet specifically allows cultural use of dog meat by indigenous people and acknowledges this might lead to limited commercial use.[184]

In the early 1980s, there was an international outcry about dog meat consumption in the Philippines after newspapers published photos of Margaret Thatcher, then British Prime Minister, with a dog carcass hanging beside her on a market stall. The British Government discussed withdrawing foreign aid and other countries, such as Australia, considered similar action. To avoid such action, the Filipino government banned the sale of dog meat. Dog meat is the third most consumed meat, behind pork and goat and ahead of beef. The ban eventually became wholly disregarded and unenforced.[185]

Thailand

There used to be a small regional culture of eating dog meat, as well as a trade of dogs for consumption and transporting them to nearby Vietnam where dog meat consumption was more common.[187] In 2014, Thailand passed the Prevention of Animal Cruelty and Provision of Animal Welfare Act which, among other provisions, made it illegal to trade in or consume dog meat.[188] As of 2016, the trade to Vietnam has continued, with CNN reporting that broken bones and crushed skulls have been a common injury for the smuggled dogs.[189]

Timor-Leste

Dog meat is a delicacy popular in Timor-Leste.[190]

Uzbekistan

Dog meat has sometimes been used in Uzbekistan in the belief that it has medicinal properties.[191][192][193][194]

Vietnam

.jpg.webp)

Around five million dogs are slaughtered in Vietnam every year, making the country the second biggest consumer of dog meat in the world after China.[195] The consumption has been criticized by many in Vietnam and around the world as most of the dogs are pets stolen and killed in brutal ways, usually by being bludgeoned, stabbed, burned alive, or having their throat slit.[196] Vietnam does not have strong regulations to stop the practice. Dog thieves are rarely punished, and neither are the people who buy and sell stolen meat. Dog meat is particularly popular in the urban areas of the north, and can be found in special restaurants which specifically serve dog meat.[65][197]

A 2013 survey on VietNamNet, with a participation of more than 3,000 readers, showed that the majority of people, at 80%, supported eating dog meat. Up to 66 percent of the readers said that dog meat is nutritious and has been a traditional food for a very long time. Some 13% said eating dog meat is okay but dog slaughtering must be strictly controlled in order to avoid embarrassing images.[198]

Dog meat is believed to bring good fortune in Vietnamese culture.[199] It is seen as being comparable in consumption to chicken or pork.[200] In urban areas, there are neighbourhoods that contain many dog meat restaurants. For example, on Nhat Tan Street, Tây Hồ District, Hanoi, many restaurants serve dog meat. Groups of customers, usually male, seated on mats, will spend their evenings sharing plates of dog meat and drinking alcohol. The consumption of dog meat can be part of a ritual usually occurring toward the end of the lunar month for reasons of astrology and luck. Restaurants which mainly exist to serve dog meat may only open for the last half of the lunar month.[200] Dog meat is also believed to raise men's libido.[200][201] There used to be a large smuggling trade from Thailand to export dogs to Vietnam for human consumption.[202] A concerted campaign between 2007 and 2014 by animal activists in Thailand, led by the Soi Dog Foundation, convinced authorities in both Thailand and Vietnam that the dog meat trade was a hindrance to efforts to tackle rabies in Southeast Asia. In 2014, Thailand introduced a new law against animal cruelty, which greatly increased penalties faced by dog smugglers. The trade had significantly diminished.[203]

In 2009, dog meat was found to be a main carrier of the Vibrio cholerae bacterium, which caused the summer epidemic of cholera in northern Vietnam.[204][205]

Prior to 2014, more than 5 million dogs were killed for meat every year in Vietnam according to the Asia Canine Protection Alliance. There are indications that the desire to eat dog meat in Vietnam is waning.[96] Part of the decline is thought to be due to an increased number of Vietnamese people keeping dogs as pets, as their incomes have risen in the past few decades.

[People] used to raise dogs to guard the house, and when they needed the meat, they ate it. Now they keep dog as pets, imported from China, Japan, and other countries. One pet dog might cost hundreds of millions of dong [100 million dong is $4,677].[96]

In 2018, officials in the city of Hanoi urged citizens to stop eating dog and cat meat, citing concerns about the cruel methods with which the animals are slaughtered and the diseases this practice propagates, including rabies and leptospirosis. The primary reason for this exhortation seems to be a fear that the practice of dog and cat consumption, most of which are stolen household pets, could tarnish the city's image as a “civilised and modern capital”.[206]

Austria

Section 6, Paragraph 2 of the law for the protection of animals prohibits the killing of dogs and cats for purposes of consumption as food or for other products.[207]

Switzerland

In 2012, the Swiss newspaper Tages-Anzeiger reported that dogs, as well as cats, are eaten regularly by a few farmers in rural areas.[208][209][210] Commercial slaughter and sale of dog meat is banned, but farmers are allowed to slaughter dogs for personal consumption. The favorite type of meat comes from a dog related to the Rottweiler and consumed as Mostbröckli, a form of marinated meat. Animals are slaughtered by butchers and either shot or bludgeoned.

In his 1979 book Unmentionable Cuisine, Calvin Schwabe described a Swiss dog meat recipe, gedörrtes Hundefleisch, served as paper-thin slices, as well as smoked dog ham, Hundeschinken, which is prepared by salting and drying raw dog meat.[211]

It is illegal in Switzerland to commercially produce food made from dog meat.[212]

Australia

Each Australian state or territory has its own regulation, but all have laws either making it illegal to eat dog meat or to kill a dog for consumption. It is also prohibited to sell dog meat based on meat processing standards and codes.[213]

Other dog products

Central Asia

According to Eurasianet, dog fat is seen as a well-established would-be treatment for tuberculosis in parts of Central Asia.[216] The fat has reportedly been used as a folk remedy for COVID-19 in Uzbekistan[217] and Kyrgyzstan.[216]

Poland

Eating dog meat is taboo in Polish culture. However, since the 16th century, fat from various animals, including dogs, was used as part of folk medicine, and since the 18th century dog fat has had a reputation as being beneficial for the lungs. According to Polityka, the main producers of dog fat in 19th and early 20th century Poland were Gypsies.[218] While making lard, or smalec, out of dogs' fat is currently discouraged in the country,[219] this practice continues in some rural areas, especially Lesser Poland.[220][221]

In 2009, Polish prosecutors reportedly found that a farm near Częstochowa was overfeeding dogs to be rendered down into lard.[222][219] According to Grazyna Zawada, from Gazeta Wyborcza, there were farms in Czestochowa, Klobuck, and in the Radom area, and in the decade from 2000 to 2010 six people producing dog lard were found guilty of breaching animal welfare laws and sentenced to jail.[218] However, the Krakow Post reported that a man who had admitted to stealing and killing dogs for lard in 2009 at Wieliczka was found not guilty of any crimes by the court, who ruled that the dogs had been slaughtered humanely for culinary purposes.[223] As of 2014, there have been new cases prosecuted.[224]

Dog breeds used for meat

The Nureongi in Korea is most often used as a livestock dog, raised for its meat, and not commonly kept as pets.[225][226] In 2015, The Korea Observer reported that many different pet breeds of dog are eaten in South Korea, including labradors, retrievers and cocker spaniels, and that the dogs slaughtered for their meat may include former pets.[160]

The Xoloitzcuintli, or Mexican Hairless Dog, is one of several breeds of hairless dog and has been used as a historical source of food for the Aztec Empire.[11]

The extinct Hawaiian Poi Dog and Polynesian Dog were breeds of pariah dog used by Native Hawaiians as a spiritual protector of children and as a source of food.[23][24]

The extinct Tahitian Dog or were a food source, and served by high ranking chiefs to the early European explorers who visited the islands. Captain James Cook and his crew developed a taste for the dog, with Cook noting, "For tame Animals they have Hogs, Fowls, and Dogs, the latter of which we learned to Eat from them, and few were there of us but what allow'd that a South Sea dog was next to an English Lamb."[227][228][229]

See also

- Speciesism

- Taboo food and drink

- Wolf meat

References

- Ann Yong-Geun "Dog Meat Foods in Korea" Archived 7 October 2007 at Wikiwix, Table 4. Composition of dog meat and Bosintang (in 100g, raw meat), Korean Journal of Food and Nutrition 12(4) 397 – 408 (1999).

- Schwabe, Calvin W. (1979). Unmentionable cuisine. University of Virginia Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8139-1162-5.

- Rupert Wingfield-Hayes (29 June 2002). "China's taste for the exotic". BBC News. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- Podberscek, Anthony L. (2009). "Good to Pet and Eat: The Keeping and Consuming of Dogs and in South Korea" (PDF). Journal of Social Issues. 65 (3): 622. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.7570. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01616.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

Dog meat is eaten nationwide and all year round, although it is most commonly eaten during summer, especially on the (supposedly) three hottest days.

- "Vietnam's dog meat tradition". BBC News. 31 December 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- Murray, Senan (6 March 2007). "Dog's dinners prove popular in Nigeria". BBC News. Retrieved 6 March 2006.

- "NOT JUST FOR CHRISTMAS: SWISS URGED TO STOP EATING CATS AND DOGS". Newsweek. 26 November 2014.

Hundreds of thousands of people in Switzerland eat cat and dog meat, particularly at Christmas, according to a Swiss animal rights group seeking to ban the practice.

- "Dachshunds Are Tenderer". Time Magazine. 25 November 1940. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- Mawson, Douglas (1914). The Home of the Blizzard.

- Czajkowski, C. (2014). "Dog meat trade in South Korea: A report on the current state of the trade and efforts to eliminate it". Animal Law. 21: 29–151.

- About THE XOLOITZCUINTLE (archived from the original on 19 July 2012), Xolo Rescue USA (archived from the original on 14 July 2012).

- Cortés, Hernan; trans. Anthony Pagden (1986). Letters from Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03799-9.

- "Hairless Dogs Revived". Life Magazine. Time, Inc.: 93 28 January 1957. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- "The great Chiefs". Native Radio. 23 February 1911. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Guts and Grease: The Diet of Native Americans (archived from the original on 25 September 2006)

- The Mexican Kickapoo Indians Felipe A. Latorre and Dolores L. Latorre (1976).

- WPA Indian Pioneer History Project for Oklahoma Ed Cooley (29 July 1937)

- WPA Indian Pioneer History Project for Oklahoma Albert Couch (12 October 1937)

- David Taube (12 September 2018), "US House members agree to ban slaughter of dogs and cats for human consumption", WDSU, retrieved 11 December 2020

- "The curious case of the dog in the..." Museum of London Blog. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Richard Madgwick. "Patterns in the modification of animal and human bones in Iron Age Wessex: revisiting the excarnation debate" (PDF). Eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

Chapter 8

- Mallher, X.; B. Denis (1989). Le Chien, animal de boucherie. pp. 81–84.

- Titcomb, M (1969). Dog and Man in the Ancient Pacific. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum Special Publication 59. ISBN 978-0-910240-10-9.

- Ellis, W (1839). Polynesian Researches. 4. London: Fisher, Jackson. ISBN 978-1-4325-4966-4.

- Mumford, David (1971). The Explorations of Captain James Cook in the Pacific. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-22766-5.

- Frederic Wood-Jones (February 1931). "The Cranial Characters of the Hawaiian Dog". Journal of Mammalogy. 12 (1): 39–41. doi:10.2307/1373802. JSTOR 1373802.

- "Bill Before Congress: Claim--Hawaii Allows 'horrific legal market' in Dog Meat". Hawaii Free Press. 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Bill would make eating your pet illegal in Hawaii". Hawaii News Now. 5 April 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Regenstein, J., Chaudry, M. and Regenstein, C. (2003), "The Kosher and Halal Food Laws". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2: 111–127. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00018.x

- Romi (1993). Histoire des festins insolites et de la goinfrerie.

- Boitani, Luige; Monique Bourdin (1997). L'ABCdaire du chien.

- "Germany's dog meat market; Consumption of Canines and Horses Is on the Increase" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 June 1907. Retrieved 20 January 2008., Bureau Of Manufactures, United States; Bureau Of Foreign Commerce (1854–1903), United States; Bureau Of Statistics, United States. Dept. of Commerce and Labor (1900). "Monthly consular and trade reports, Volume 64, Issues 240–243". United States. Bureau of Manufactures, Bureau of Foreign Commerce, Dept. of Commerce. Retrieved 29 September 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Use Horse and Dog Meat – Germans forced to that diet by high price of other meat" (PDF). The New York Times. 1900.

- "American Food in Germany" (PDF). The New York Times. 1898.

...the German breeders... heightened the price to such an extent that horse, and even dog's meat, has become staple with the poorer classes in certain districts, and notably in the large cities

- "Miners eat horses and dogs" (PDF). The New York Times. 1904.

- "Meat Shops Closed As Belgians Go Hungry" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 July 1916.

We found the meat shops all closed, ... with three exceptions, namely; shops that have recently and openly sold dog meat.... The average price were 12 francs a kilo, bones and all, (about $1.30 a pound) and some meat that had been obtained by special exertions for the soup kitchens.

- "FEAR OF FAMINE APPALS AUSTRIA; Charges of Cannibalism by Vienna Workmen Are Officially Hushed Up. PEOPLE JEER AT THE WAR. German Promises of Victory Flouted—Soldiers Beg for Bread and Long for Peace. Quarantine Against Bolshevism. Real Famine in the Country. Saxons Eat Camels and Dogs", The New York Times, 22 May 1918

- "DOGS AS MEAT IN MUNICH; Butcher's Shop Hangs Sign Offering Either to Buy or Sell". The New York Times. 1923.

- "GERMANS STILL EAT DOGS; Berlin Police Chief Issues Rules for Inspection of the Meat". The New York Times. 1925.

- "Fleischbeschaugesetz (Meat Inspection Law), § 1a". Reich Law Gazette. 1937. p. 458. then becoming § 1 para. 3, RGBl. 1940 I p. 1463 (in German)

- "NETHERLANDERS SEEK SUNDAY MEAT IN VAIN; Food Situation Becomes Acute as Nazis Seize Dog Sausage". The New York Times. 8 December 1940. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- "Benedict Allen: my greatest mistake".

- "Marco Lavoie, Stranded Hiker, 'Eats His Dog To Survive'". Huffington Post. 2 November 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Back Through the Gorge, 1806". Lewis-clark.org. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "Ecola". Lewis-clark.org. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "Change of Heart". Lewis-clark.org. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "Lewis and Clark Through Nez Perce Eyes". lewis-clark.org. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- "Lemhi Pass to Fort Clatsop". Lewis-clark.org. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "September 17, "Sinque Hole Camp"". Lewis-clark.org. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "Sex, Dog Meat, and the Lash: Odd Facts About Lewis and Clark". News.nationalgeographic.com. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "What Lewis and Clark Ate - The History Kitchen - PBS Food". Pbs.org. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Clarkson, Janet (24 December 2013). Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Years of World Culinary History, Culture, and Social Influence. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 347–. ISBN 978-1-4422-2715-6.

- Bown, Stephen R. (2012). The Last Viking: The Life of Roald Amundsen. Da Capo Press. pp. 165–166.

- Amundsen, Roald. "The South Pole". Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Eric Thys & Olivier Nyssens Préparation et commercialisation de la viande canine chez les Vamé Mbrémé population animiste des monts Mandara. in "Tropical Animal Production for the Benefit of Man. Antwerp, 1982, pp. 511–517.

- "Dog meat back on menu in Democratic Republic of Congo". 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Simoons, Frederick J. (1994). Eat not this flesh: food avoidances from prehistory to the present (2 ed.). Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-299-14254-4.

- "I still stand by my dog meat factory in Ghana -Hon Karbo". TV3 Ghana. 13 April 2017.

- "Dog Meat Factory Proposed in Ghana". In Defense of Animals. 19 April 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Evaluation of dog slaughter and consumption practices related to the control of rabies in Nigeria". June 2013.

- Volk, Willy (7 March 2007). ""Man bites dog": Dining on dog meat in Nigeria". gadling.com.

- Shobayo, Isaac. "EBOLA: Jos residents shun bush meat, stick to dog meat". tribune.com.ng. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014.

- "'It's a sin': Cambodia's brutal and shadowy dog meat trade". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- The Dog and Cat Meat Trade in Southeast Asia: A Threat to Animals and People Harvard Kennedy School, February 2020 (PDF; Page 21)

- Hong Tuyet (24 December 2016). "47 dogs seized as police bust dog meat ring in southern Vietnam". VnExpress. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Nibert, David (2017). Animal oppression and capitalism. p. 120. ISBN 9781440850745. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "农业部关于印发《生猪屠宰检疫规程》等4个动物检疫规程的通知". Ministry of Agriculture. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Chinese Ministry of Agriculture (2001). 畜禽屠宰卫生检疫规范(NY 467-2001). China Standard Pres. pp. 3–4. ISBN 155066213877.CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

- Fullerton, J. (22 June 2015). "Yulin dog meat festival: Chinese city retains its appetite despite months of protests". The Independent. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Wade, Nicholas (7 September 2009). "In Taming Dogs, Humans May Have Sought a Meal". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- Liang Shih-chiu (2005). Ya she xiao pin xuan ji. Chinese University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-962-996-219-7. Translated by Ta-tsun Chen.

- Simoons, Frederick J. (1991). Food in China: a cultural and historical inquiry. CRC Press. pp. 24, 38, 149, 305, 309–315, 317, 332. ISBN 978-0-8493-8804-0.

- "Dog meat row hits HK chain". BBC News. 4 August 2002.

- Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi (2007). The Nanking atrocity, 1937–38: complicating the picture (illustrated ed.). Berghahn Books. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-84545-180-6.

- "How many cats & dogs are eaten in Asia? AP 9.03". animalpeoplenews.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012.

- "Inside the cat and dog meat market in China". cnn.com.

- "Tech-savvy citizen rescues 69 dogs from becoming dinner". Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- O'Neil, L. (22 June 2015). "Dog meat festival in China takes place despite massive online protest". CBC News. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "Southwest China hospital staff ordered to stay away from 'dog meat festival'". South Morning China Post. 13 June 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- "陝西榆林10天美食節 1萬5千隻狗慘遭下肚 | 大陸新聞 | NOWnews 今日新聞網". Nownews.com. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- "China Yulin dog meat festival under way despite outrage". BBC. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- "The truth about the Yulin dog meat festival – and how to stop it". Animals Asia Foundation. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- "This Chinese dog-eating festival's days are numbered thanks to a massive social media campaign". Business Insider. 30 June 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Fullerton, J. (17 June 2015). "Yulin Dog Meat Festival: Netizens rally in defence of event that will see 10,000 cats and dogs slaughtered". The Independent. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Celebrities join campaign to stop dog meat festival in China". AsiaOne. Singapore Press Holdings Ltd. Co. 18 June 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

Thousands of dogs are traded, killed, and then eaten in the home or on the street. Some of them are burnt or boiled alive.

- "Activists protest dog-eating tradition". china.org.cn. 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Huifeng, H. (2014). "Dog-eating festival loses its bite as animal rights activists step in". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- "Millions of Chinese Want the Yulin Dog Meat Festival to Stop". Time. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Dog meat festival begins in China". BBC News. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Kaiman, Jonathan (23 June 2014). "Chinese dog-eating festival backlash grows". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Poll: Majority of Chinese public wants Yulin dog meat festival shut down : Humane Society International". hsi-old.pub30.convio.net. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Guangzhou bans eating snakes—ban helps cats". Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- China bans dog from Olympic menu, BBC News, 11 July 2008.

- Li Xianzhi, 2010-01-27, Eating cats, dogs could be outlawed Archived 23 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Xinhua News Agency

- "China to jail people for up to 15 days who eat dog". China Daily. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Rosen, E. (2014). "To eat dog, or not to eat dog". The Atlantic. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Kaiman, J. "Chinese dog-eating festival backlash grows". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Sun, C. (2015). "Dog meat restaurant in Guangzhou closes amid 'falling demand'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "SPECIAL REPORT: Almost 9 million Chinese back bill to end cat and dog meat eating". animalsasia.org. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Chinese city bans the eating of cats and dogs". BBC News. 2 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "China's Shenzhen bans the eating of cats and dogs after coronavirus". Reuters. 2 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "BREAKING: A second city in mainland China just banned eating of dogs, cats and wildlife in hoped for "domino effect"". Humane Society International. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "BREAKING: Shenzhen becomes mainland China's first city to ban eating of dogs, cats and wildlife in consumption and trade crackdown". Humane Society International. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Nicole Pallotta (20 May 2020). "China Reclassifies Dogs from "Livestock" to "Companion Animals"". Animal Legal Defense Fund. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Standaert, Michael (9 April 2020). "China signals end to dog meat consumption by humans". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Dogs and cats ordinance". Department of Justice (Hong Kong). 6 January 1950. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Slaughter of dog or cat for food prohibited". Department of Justice (Hong Kong). 30 June 1997. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- "Slaughter of dog or cat for food – Penalty". Department of Justice (Hong Kong). 30 June 1997. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- "First Case Imprisonment in HK for Dog Meal". 29 May 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2006.

- Cheng, Jonathan (23 December 2006). "Dog-for-food butchers jailed (DUBIOUS first case)". The Standard – China's Business Newspaper. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- "Taiwan bans dog meat". BBC News. 2 January 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- "Taiwan law takes bite out of dog meat sales". 17 December 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Serusha Govender (11 April 2014). "9 Countries That Eat Cats and Dogs (Slideshow)". The Daily Meal. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "Taiwan becomes first country in Asia to ban eating of cat and dog meat". 10 April 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Zeldin, Wendy (18 October 2017). "Taiwan: Animal Protection Law Amended | Global Legal Monitor". www.loc.gov.

- Simoons, Frederick J. (1994). Eat Not this Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-299-14254-4.

- "Dog meat, a delicacy in Mizoram". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 December 2004. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Tribal Naga Dog meat delicacy". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Manipur – a slice of Switzerland in India". The Times of India. Chennai, India. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- "India's Nagaland state announces an end to its brutal dog meat trade, sparing 30,000 dogs a year". Humane Society International. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- News, Agency. "Mizoram passes Bill against dog meat trade". pennews. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Pet lovers in Nagaland campaign against animal cruelty". easternmirrornagaland.com. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Nagaland bans sale, consumption of dog meat in state; import and trading of dogs deemed illegal as well - India News, Firstpost". Firstpost. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Nagaland Cabinet bans sale of dog meat". The Indian Express. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Shepherd, Jack, All About Indonesian Dog Meat, BuzzFeed

- Cochrane, Joe (25 March 2017). "Indonesians' Taste for Dog Meat Is Growing, Even as Others Shun It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "A taste for dog: Indonesia trade persists despite crackdown". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Appetite for dog meat persists in Indon". 10 April 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Max Walden (8 November 2017). "Deadly as well as disgusting? Dog meat targeted by activists in Indonesia". Asian Correspondent. Archived from the original on February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Jane Dalton (23 May 2018). "Dogs and cats blowtorched alive and bludgeoned to death at Indonesian street markets". The Independent. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Natashya Gutierrez (30 September 2015). "Clubbed to death, blowtorched: Indonesia's dog-eating culture". Rappler. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Mercato shock in Indonesia, dai cani ai pitoni arrosto in vendita". adnkronos. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- "Minahasa" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- "Obama: When I Ate a Dog" – via YouTube.

- "Obama Jokes About Eating Dog: 'A Pitbull is Delicious'".

- Staff (30 April 2012). "President Obama's humor goes to the 'dogs' during annual dinner". CNN Politics. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- James Thomas and Lesley Robinson (19 June 2017). "Evidence shows dogs in Bali are being brutally killed and the meat sold to unsuspecting tourists". ABC.

- Rachel Hosie (19 June 2017). "Bali tourists are unknowingly eating dog meat, undercover investigation reveals". Independent.

- "【犬食文化】東京のコリアンタウン新大久保に犬肉を食べに行く - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- News, Kyodo. "Alliance launched to push for dog meat ban in Asia". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- staff, Asia Times (16 April 2019). "Asia-based alliance to fight for dog meat ban". Asia Times. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Hanley, Susan B. (1999). Everyday things in premodern Japan: the hidden legacy of material culture. University of California Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-520-21812-3.

- A Study of the favorite Foods of the Balhae People Yang Ouk-da

- "Hot weather boosts dog meat consumption in North Korea". CBS News. 27 July 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- "Humane Society International". Humane Society International. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Dog meat farmer in South Korea swaps pups for plants in animal charity's pioneering program to phase out the brutal trade". Humane Society International. 9 October 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "HSI/Canada helps rescue 200 dogs from horrific South Korean dog meat farm". Humane Society International. 14 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "개고기는 法규제 자체가 없어 뭐가 얼마나 들었는지 모른다". News.chosun.com. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "개고기 값은 폭락하는데 보신탕값 그대로". M.seoul.co.kr. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "'초복의 두얼굴' 성남 모란시장 앞에서 '동물위령제'…상인들은 거센 반발". Sports.khan.co.kr. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "점심·저녁 예약 '0건'… 초복인데 유명 보신탕집 썰렁한 이유". Dt.co.kr. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "한국 '강아지 공장'서 버려진 애완견들 미국으로 - 미주 한국일보". Ny.koreatimes.com. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Pettid, Michael J., Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History, London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2008, 84–85.

- Kim 2008, p. 209

- Kim, Rakhyun E. (2008). "Dog Meat in Korea: A Socio-Legal Challenge" (PDF). Animal Law Review. 14 (2): 231. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2011.

- "Dog Meat to Be Subject to Livestock Rules". The Chosun Ilbo. 24 March 2008.

- 국민 절반 '개고기 축산물로 관리해야 한다' [Half of citizens [say] 'Dog Meat Should be Controlled as Livestock Product']. The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). 28 March 2008. (Translation)

- Podberscek, Anthony L. (2009). "Good to Pet and Eat: The Keeping and Consuming of Dogs and Cats in South Korea" (PDF). Journal of Social Issues. 65 (3): 615–632. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.7570. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01616.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- Dog Meat Foods in Korea, Ann, Yong-Geun, Korean Medical Database

- Hyams, J. (15 January 2015). "Former pets slaughtered for dog meat across Korea". The Korea Observer. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Rogers, Martin. "Winter Olympics shines spotlight on dog meat trade in South Korea". USA TODAY. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Do Koreans Really Eat Dog? about.com

- "South Korea promotes dog meat". BBC News. 13 January 2002.

- Claire Czajkowski (2014). DOG MEAT TRADE IN SOUTH KOREA: A REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE OF THE TRADE AND EFFORTS TO ELIMINATE IT (page 7). Lewis & Clark Law School.

- Martin Rogers (February 2018). "Winter Olympics shines spotlight on dog meat trade in South Korea". USA Today.

- Hopkins, Jerry; Bourdain, Anthony; Freeman, Michael (2004). Extreme Cuisine: The Weird & Wonderful Foods That People Eat. Tuttle Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7946-0255-0.

- 보신탕 논란, 그 해법은? [Bosintang Controversy: What is the Solution?] (in Korean). National Assembly Tele Vision. 9 August 2006. (Translation)

- Kim, Rakhyun E. (2008). "Dog Meat in Korea: A Socio-Legal Challenge" (PDF). Animal Law Review. 14 (2): 202. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2011.

- South Korea's dog day, BBC News, 17 August 1999.

- "복날 신풍속…10년새 서울 보신탕집 절반 문 닫았다". Asiae.co.kr. 17 July 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "Largest Dog Meat Slaughterhouse in South Korea Shuts Down - The Sentinel". Sentinelassam.com. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Wilkinson, Bard (22 November 2018). "South Korea closes largest dog meat slaughterhouse". CNN. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Humane Society International. "Closing South Korea's dog meat farms : Humane Society International". Hsi.org. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Dailynk.com". Dailynk.com. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "Not illegal in Malaysia to eat dog and cat meat". The Star. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Dog & cat meat - Philippines". ESDAW. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Metro Manila Commission Ordinance 82-05". Archived from the original on 16 December 2005.

- "The Animal Welfare Act 1998". Retrieved 30 August 2006.

- Caluza, Desiree (17 January 2006). "Dog meat eating doesn't hound Cordillera natives". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 19 February 2006. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- "Koreans fuel dog meat trade in Baguio". ABS-CBN. 8 November 2012.

- Catajan, Maria Elena (18 June 2017). "Korean restos in Baguio suspected of serving dog meat". SunStar. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "The Dog Meat Trade". Animal Welfare Institute. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Neville G. Gregory; Temple Grandin (12 March 2007). Animal Welfare and Meat Production. CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-216-9.

- "Resolution 05-392". Province of Benguet. 17 January 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- Chase, A. (2002). "Strange foods". Gastronomica. 2 (2): 94–96. doi:10.1525/gfc.2002.2.2.94. JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2002.2.2.94.

- Lam, Lydia (17 February 2017). "AVA investigating suspected case of dog meat sale highlighted by actor Andrew Seow". The Straits Times. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Fuller, Thomas (1 November 2014). "Dog Meat Trade in Thailand Is Under Pressure and May Be Banned". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Klangboonkrongthe, Manta (13 February 2015). "New Thai law against animal cruelty puts burden on humans". AsiaOne.

- Anna Coren (21 July 2016). "THAILAND:DOG MEAT TRADE DOG RESCUES". CNN.

- "Democratic Republic of East Timor". catfeedingadvisor.com. p. 3.

- "Dog meat restaurants spring up in Uzbekistan". Uznews.net. 2009. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Anvar Mahkamov (2006). "Meat is Medicine". Transitions Online. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Letter From Uzbekistan". Newsweek. 5 November 2001. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Dog meat is believed to be a TB medicine in Andizhan". Enews.fergananews.com. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Vietnam kills at least 5 million dogs a year, mostly in brutal ways". VnExpress. 14 October 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Hodal, Kate (27 September 2013). "How eating dog became big business in Vietnam". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "How eating dog became big business in Vietnam". The Guardian. 14 October 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- "80 percent of Vietnamese still support eating dog meat". 20 April 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- "Vietnam closes 60 dog meat slaughterhouses and restaurants after cholera bacteria found". Guelph Mercury. 12 July 2010.

- "Vietnam's dog meat tradition". BBC News. 31 December 2001.

- Avieli, Nir (2011). "DOG MEAT POLITICS IN A VIETNAMESE TOWN". Ethnology. 50 (1): 59–78. ISSN 0014-1828.

- Hodal, Kate. "How eating dog became big business in Vietnam". the Guardian.

- The Little Orange Book. https://www.soidog.org/sites/default/files/Soi_Dog_Foundation_Little_Orange_Book.pdf: Soi Dog Foundation. 2018. pp. 11–13.

- "Hanoi dog meat restaurants come under scrutiny after cholera outbreak". Vietnamnet. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- "Cholera, bird flu present, but VN still A/H1N1-free". Vietnamnet. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2009. Retrieved from Internet Archive 12 January 2014.

- "Vietnamese capital Hanoi asks people not to eat dog meat". BBC News. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "Federal law that enacts an animal protection law and changes the Federal Constitutional Law, the 1994 Trade Regulations and the 1986 Federal Ministries Act". Das Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes (legal information system of the federal government) (in German).

- "Dogs and cats 'still eaten in Switzerland'". thelocal.ch.

- "Forget chocolate or cheese: Cat and dog meat is Swiss delicacy". scotsman.com.

- "Schweizer sollen keine Hunde und Katzen mehr essen". Tages Anzeiger.

- Schwabe 1979, p. 173

- FDHA Ordinance of 23 November 2005 on food of animal origin, Art.2.

- "Is eating cats or dogs legal?". Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "SPCA: Eating pets more common than thought". TVNZ. 17 August 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Man escapes charges for barbecuing pet dog". CNN. 2009.

- Ayzirek Imanaliyeva (13 August 2020). "Fighting COVID in Kyrgyzstan: Dog fat, ginger and bloodletting". Eurasianet. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "Central Asian governments admit they have a problem with covid-19". The Economist. 23 July 2020. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Dorota Szumińska (25 October 2008). "Chce się wyć". Polityka.

- Day, Matthew (7 August 2009). "Polish couple accused of making dog meat delicacy". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- JANET M. DAVIS (7 May 2012). "Opinion | The Dog Ate My Birth Certificate". The New York Times.

- Jacobsson, Kerstin (December 2012). "Fragmentation of the collective action space: the animal rights movement in Poland". East European Politics. 28 (4): 353–370. doi:10.1080/21599165.2012.720570. ISSN 2159-9165. S2CID 144181787.

- "Poland prosecutors probe dog lard sale". United Press International. 10 August 2009.

- "Killing Dogs OK in Poland". Krakow Post. 21 October 2009.

- "Psi smalec. Przeraźliwy skowyt zarzynanych psów".

- Morris, Desmond (2008). Dogs: The Ultimate Dictionary of Over 1,000 Dog Breeds. Trafalgar Square. ISBN 978-1-57076-410-3.

- Podberscek, Anthony L. (2009). "Good to Pet and Eat: The Keeping and Consuming of Dogs and in South Korea" (PDF). Journal of Social Issues. 65 (3): 623. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.7570. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01616.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- Salmond, Anne (2003). The Trial of the Cannibal Dog: The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook's Encounters in the South Seas. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-300-10092-1. OCLC 249435583.

- Heringman, Noah (4 April 2013). Sciences of Antiquity: Romantic Antiquarianism, Natural History, and Knowledge Work. Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780191626067. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Holland, Leandra Zim (22 January 2004). Feasting and Fasting with Lewis & Clark: A Food and Social History of the Early 1800s. Emigrant, Montana: Old Yellowstone Publishing, Sweetgrass Books. p. 189. ISBN 9781591520078.

Further reading

- Kim, Rakhyun E. (2008). "Dog Meat in Korea: A Socio-Legal Challenge". Animal Law. 14 (2): 201–236. SSRN 1325574.

- Yong-Geun Ann, Ph.D. Dog Meat (in Korean and English). Hyoil Book Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2009. (contains some recipes)

- Dressler, Uwe; Alexander Neumeister (1 May 2003). Der Kalte Hund (in German). Dresden: IBIS-Ed. ISBN 978-3-8330-0650-0.

- Zawada, Grazyna (28 October 2010). "Szesc psow w sloiku". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- Aisin Gioro, Ulhicun; Jin, Shi. "Manchuria from the Fall of the Yuan to the rise of the Manchu State (1368-1636)" (PDF). Retrieved 10 March 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dog meat. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |