Palm Sunday tornado outbreak sequence of April 10–12, 1965

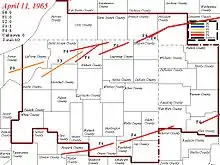

On April 10–12, 1965, a devastating severe weather event affected the Midwestern and Southeastern United States. The tornado outbreak sequence produced 55 confirmed tornadoes in one day and 16 hours.[nb 2] The worst part of the outbreak occurred during the afternoon hours of April 11 into the overnight hours going into April 12. The second-biggest tornado outbreak on record at the time, this deadly series of 48 tornadoes, which became known as the 1965 Palm Sunday tornado outbreak, inflicted a 450 miles long (724 km) swath of destruction from Cedar County, Iowa, to Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and a swath 450 miles long (724 km) from Kent County, Michigan, to Montgomery County, Indiana. The outbreak lasted 16 hours and 35 minutes and is among the most intense outbreaks, in terms of number, strength, width, path, and length of tornadoes, ever recorded, including at least four "double/twin funnel" tornadoes. In all, the outbreak killed 266 people, injured 3,662 others, and caused $1.217 billion (1965 USD) in damage.

| |

| Type | Tornado outbreak sequence |

|---|---|

| Duration | April 10–12, 1965 |

| Tornadoes confirmed | 55 confirmed[1] |

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Duration of tornado outbreak2 | 1 day and 16 hours |

| Highest gust | 70 kn (81 mph; 130 km/h) at three locations on April 11[2] |

| Largest hail | 2 in (5.1 cm) at seven locations on April 10–12[3] |

| Damage | $1.217 billion (1965 USD)[nb 1][4] $9.87 billion (2021 USD) |

| Casualties | 266 fatalities, 3,662 injuries |

| Areas affected | Southern and Midwestern United States (Upland South, Driftless Area, and Great Lakes region, primarily Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan) |

Part of the tornadoes and tornado outbreaks of 1965 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale 2Time from first tornado to last tornado | |

Background

A vigorous extratropical cyclone centered over the northeastern High Plains, in the region of the Dakotas, was the primary catalyst for widespread severe weather on April 11, 1965. As early as the preceding day, a strong jet stream in the upper two-thirds of the troposphere traversed the southern Great Plains and was responsible for an outbreak of tornadoes from the Kansas–Missouri border to Central Arkansas, including a violent tornado that struck the town of Conway in Faulkner County, Arkansas, killing six people and injuring 200.[10][11] The following morning, at 7:00 a.m. CDT (12:00 UTC), data from radiosondes indicated wind speeds of 120–150 kn (140–170 mph; 220–280 km/h) between the altitudes of 18,000–30,000 ft (5,500–9,100 m) over the Sonoran–Chihuahua Deserts and the Arizona/New Mexico Mountains. Meanwhile, at 10,000 ft (3,000 m), winds of 70 kn (81 mph; 130 km/h) impinged on the southern Great Plains. Retreating northward, a warm front interacted with a shortwave to produce isolated thunderstorms from northern Missouri and Central Illinois to the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.[11][12]

The well-defined surface cyclone over the High Plains intensified as it headed into Iowa, its central pressure decreasing from 990 to 985 mb (29.23 to 29.09 inHg) by 1:00 p.m. CDT (18:00 UTC). As the warm front bisected central Iowa and stretched into Illinois and Indiana, a cold front and very dry air aloft—indicative of a potent elevated mixed layer—departed from eastern Kansas.[12] Strong winds transported steep lapse rates within the elevated mixed layer eastward across the Great Plains. Concomitant destabilization of the atmosphere occurred over the warm sector due to abundant sunshine from the elevated mixed layer.[10][11] High temperatures ranged from 83 to 85 °F (28 to 29 °C) from Chicago to St. Louis.[12][13] Simultaneously, a strong low-level jet stream brought a moistening air mass northward: dew points of at least 60 °F (16 °C) reached southernmost Illinois and Indiana by 10:00 a.m. CDT (15:00 UTC).[10][11][12] Meanwhile, a pronounced dry line-like boundary near the cold front moved into eastern sections of Arkansas and Missouri.[12] Weather stations from Topeka, Kansas, to Peoria, Illinois, showed very strong vertical shear that favored intense low-level convergence—combined with a moist dew point in the warm sector, an environment favorable for supercell thunderstorms.[12]

A weather balloon launched from Dodge City, Kansas, recorded winds of 185 mph (298 km/h) aloft; another at Peoria, Illinois, subsequently measured 135 kn (155 mph; 250 km/h).[14][10] Minimum dew points of 60 °F (16 °C) reached as far north as southern Michigan by mid afternoon. Volatile atmospheric conditions led to thunderstorm activity over eastern Iowa by 1:40–48 p.m. CDT (18:40–48 UTC), the first supercell of which produced the initial tornado of the day.[11][10][15] By 6:00 p.m. CDT (23:00 UTC), instability reached record proportions for the time of year over a wide area, with convective available potential energy (CAPE) of at least 1,000 j/kg in the mixed layer over much of Indiana and southernmost Michigan. Record-breaking ambient vertical wind shear in the lowest 6 km (3.7 mi; 20,000 ft; 6,000 m) of the atmosphere facilitated the explosive development of long-lived mesocyclones and thus long-tracked tornado families. The very strong shear and rapid forward speed of the storms—up to 70 mph (110 km/h) in some cases—may have enhanced the formation of cyclic supercells and could account for numerous reports of multiple mesocyclones and twin tornadoes, including the famous "twin tornadoes" near Elkhart, Indiana; similar conditions yielded the Tri-State Tornado, the longest-tracked and deadliest in U.S. history, on March 18, 1925.[10][16]

At 11:45 a.m. CDT (16:45 UTC) on April 11, the Severe Local Storms Unit (SELS) in Kansas City, Missouri, issued an outlook that mentioned the possibility of tornadoes from northeastern Missouri to the northernmost two-thirds of Indiana.[nb 3] At 2:00 p.m. CDT (19:00 UTC)—fifteen minutes after the first tornado was spotted—the first tornado watch of the day was issued, covering portions of northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin.[10][18] A total of four watches were issued on April 11–12.[nb 4][23] Radio news reporter Martin Jensen, then stationed at the WMT Station in Cedar Rapids, reported the first tornado of the day forming at 1:45 p.m. CDT (18:45 UTC). The station was equipped with a Collins Radio aviation radar mounted on the roof of the station building and was used to support severe weather reports on local and regional newscasts. After detecting the severe thunderstorm, the reporter called Weather Bureau offices in Waterloo (which had no radar) and Des Moines to alert them about the storm. The phone call became the first hard evidence for the Weather Bureau regarding the growing threat of severe storms that spawned dozens of tornadoes over the next 12 hours. For the first time in the U.S. Weather Bureau's history, an entire Weather Bureau Office's jurisdiction, in Northern Indiana, was under a tornado warning; this was termed a "blanket tornado warning" and was later used by several National Weather Service (NWS) offices on April 3, 1974.[24][13][25]

Outbreak statistics

| State | Total | County | County total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas | 6 | Faulkner | 6 |

| Iowa | 1 | Cedar | 1 |

| Illinois | 6 | McHenry | 6 |

| Indiana | 137 | Adams | 1 |

| Boone | 20 | ||

| Elkhart | 62 | ||

| Grant | 8 | ||

| Hamilton | 6 | ||

| Howard | 17 | ||

| Lagrange | 10 | ||

| Marshall | 3 | ||

| Montgomery | 2 | ||

| St. Joseph | 3 | ||

| Starke | 4 | ||

| Wells | 1 | ||

| Michigan | 53 | Allegan | 1 |

| Branch | 18 | ||

| Clinton | 1 | ||

| Hillsdale | 6 | ||

| Kent | 5 | ||

| Lenawee | 9 | ||

| Monroe | 13 | ||

| Ohio | 60 | Allen | 11 |

| Cuyahoga | 1 | ||

| Delaware | 4 | ||

| Hancock | 2 | ||

| Lorain | 17 | ||

| Lucas | 16 | ||

| Mercer | 2 | ||

| Seneca | 4 | ||

| Shelby | 3 | ||

| Wisconsin | 3 | Jefferson | 3 |

| Totals | 266 | ||

| All deaths were tornado-related | |||

Confirmed tornadoes

| FU | F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 16 | 14 | 6 | 18 | 0 | 55 |

| "FU" denotes unclassified but confirmed tornadoes. | |||||||

April 10 event

| F# | Location | County / Parish | State | Start coord. |

Time (UTC) | Path length | Max. width | Summary | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0 | WNW of Iatan | Platte | MO | 39.48°N 95.03°W | 19:30–? | 2 miles (3.2 km) | 100 yards (91 m) | This tornado struck Bean Lake. Losses totaled $30. | [27][28][29] |

| F3 | ESE of Potter to NNW of Agency, MO | Leavenworth (KS), Platte (MO), Buchanan (MO) | KS, MO | 39.42°N 95.12°W | 20:15–21:00 | 23.2 miles (37.3 km) | 200 yards (180 m) | This intense tornado family began near Lowemont in Leavenworth County, Kansas, and reformed near Bean Lake, Missouri. Losses totaled $25,000 in Leavenworth County. As it crossed into Missouri, the tornado family pushed a 25-foot-high (7.6 m) "wall of water" across Bean Lake. In Platte County the tornado family destroyed 25 trailers and unroofed the auditorium at Lakeview School. Communication wires and barns were also damaged near Weston. 11 people were injured: nine in Platte County and two in Butte County. Losses totaled $525,000, including $250,000 each in Platte and Buchanan counties. Along the path farms were extensively damaged, homes unroofed, and walls blown away. | [30][31][32][33][34][35][36] |

| F2 | NW of Osborn to SSW of Weatherby | DeKalb | MO | 39.78°N 94.42°W | 21:15–21:25 | 9.6 miles (15.4 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | This tornado destroyed or damaged outbuildings and barns. Eight farms were impacted and four homes were destroyed. Seven people were injured. Losses totaled $250,000. Tornado researcher Thomas P. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F3. | [37][38][34] |

| F2 | Edinburg to ENE of Tindall | Grundy | MO | 40.08°N 93.7°W | 22:45–23:15 | 10.3 miles (16.6 km) | 100 yards (91 m) | This tornado was associated with the same thunderstorm that produced the Bean Lake F3. Roofs in Edinburg were damaged. A church, trees, barns, and homes were damaged or destroyed. The tornado also wrapped a 2-short-ton (1.8 t; 1,800 kg) truck around a tree. One person was injured in Grundy County. Losses totaled $250,000. | [39][40][34] |

| F2 | SE of Jamesport to S of Trenton | Daviess, Grundy | MO | 39.95°N 93.78°W | 23:00–23:30 | 11.1 miles (17.9 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | This tornado impacted five farms. Homes and a few barns were unroofed, destroyed, or otherwise damaged. The tornado flipped a trailer in Grundy County, injuring a woman inside. Losses totaled $50,000. | [41][42][43][34] |

| F4 | Southeastern Conway | Faulkner | AR | 35.05°N 92.45°W | 00:26–00:35 | 4.7 miles (7.6 km) | 200 yards (180 m) | 6 deaths – This violent tornado extensively damaged or destroyed 185 homes in Conway, a block-long swath of which sustained F4-level damage. 200 injuries occurred, of which 100 required hospitalization. Losses totaled $25 million. | [44][45][34] |

| F1 | NW of La Tour | Cass | MO | 38.65°N 94.12°W | 01:30–? | 0.2 miles (0.32 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | Three farms were damaged. Losses totaled $25,000. | [46][47] |

April 11 event

| F# | Location | County / Parish | State | Start coord. |

Time (UTC) | Path length | Max. width | Summary | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | SSW of Keefeton | Muskogee | OK | 35.58°N 95.35°W | 09:30–? | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This brief, strong tornado destroyed a 30-by-75-foot (9.1 by 22.9 m) barn. With a "big roar" the tornado moved a sheet-metal garage 2 ft (0.61 m) off its foundation and spread debris over a wide area. The tornado also tore sheet-metal roofing from the barn into fragments, parts of which were found hanging in trees. Losses totaled $2,500. Grazulis did not list the tornado as an F2 or stronger. | [48][49][50][51] |

| F4 | SSW of Lowden to NE of Springbrook | Cedar, Clinton, Jackson | IA | 41.85°N 90.93°W | 18:55–? | 91.5 miles (147.3 km) | 200 yards (180 m) | 1 death – This violent tornado may have first begun just east of Tipton. It went on to strike 25 farms, one of which it leveled. Fragments of the farmhouse were found 1 mi (1.6 km) distant. A man near Lowden died of severe injuries a month after the tornado. Three other people sustained nonlethal injuries. Damages amounted to at least $500,000 and are officially listed as $5 million. Unofficial estimates of the path length vary: some sources range from 30 to 40 mi (48 to 64 km). | [52][53][54][55][35] |

| F1 | S of Fredericksburg to NNW of Elon | Chickasaw, Fayette, Winneshiek, Allamakee | IA | 42.93°N 92.2°W | 19:15–? | 49.9 miles (80.3 km) | 300 yards (270 m) | This long-lived, intermittent tornado caused considerable damage near Ossian and skipped past Waukon. The tornado also passed through Alpha and Moneek. Losses totaled $250,000. | [56][57][55][35] |

| F1 | NW of Winslow to N of Albion, WI | Stephenson (IL), Green (WI), Rock (WI), Dane (WI) | IL, WI | 42.5°N 89.8°W | 20:00–21:00 | 27.1 miles (43.6 km) | 167 yards (153 m) | This tornado family may have first uprooted a grove of 15 trees near Stockton, Illinois, and left debris beside the Illinois Central Railroad between Warren and Lena. Confirmable damage began near Winslow, crossed into Wisconsin, and worsened in severity. The tornado family destroyed or damaged 400 cars, 55 businesses, and 65 homes in northwestern Monroe. A motel was unroofed just north of town as well. The tornado family also destroyed barns and other structures on 57 farms. Homes and trailers were unroofed, destroyed, or shorn of walls near Evansville. The tornado family also impacted Albany. At least 40 people—possibly 47—were injured and losses totaled $5 million. Grazulis classified the tornado family as an F2 and split the event into two tornadoes. | [58][59][60][61][62][55] |

| F2 | SSW of Aztalan to Eastern Watertown | Jefferson | WI | 43.03°N 88.88°W | 20:30–21:30 | 14.5 miles (23.3 km) | 1,320 yards (1,210 m) | 3 deaths – This large tornado began near Jefferson and rapidly widened to 3⁄4 mi (1.2 km) across. As it neared Wisconsin Highway 30—presently Interstate 94—the tornado "practically leveled" a forest. Shortly thereafter, the tornado struck the community of Pipersville; nearby, it tossed two cars off Wisconsin Highway 16 (then part of U.S. Route 16), killing three of their occupants. The tornado also destroyed buildings on 20 farms. At least 28 people (possibly 35) were injured and losses totaled $2.5 million. Grazulis classified the tornado as a near-F4. | [63][64][55][62] |

| F1 | ESE of Mount Sterling to WNW of Bosstown | Crawford | WI | 43.3°N 90.9°W | 20:45–? | 13.3 miles (21.4 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This tornado destroyed at least one barn near Soldiers Grove. The tornado also struck Gays Mills. Losses totaled $25,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F2. | [65][66][55] |

| F4 | Lakewood to Island Lake | McHenry, Lake | IL | 42.22°N 88.38°W | 21:20–21:42 | 9.1 miles (14.6 km) | 400 yards (370 m) | 6 deaths – See section on this tornado – 75 people were injured and losses totaled $1.5 million. | [67][68][69][70][23][71][72][55] |

| F2 | NW of Third Lake to W of Gurnee | Lake | IL | 42.38°N 88.02°W | 21:50–? | 4.5 miles (7.2 km) | 200 yards (180 m) | Related to the previous event, this tornado began as a waterspout over Druce Lake. Continuing to the east, the tornado damaged more than 12 homes, a few of which were unroofed; large, fallen trees damaged one or more of the homes as well. The tornado then traversed 2 mi (3.2 km) of wooded and marshy wilderness before striking an orchard and destroying a farm. Further along, some damage also occurred to garages and sheds before the tornado apparently dissipated. Losses totaled $250,000. | [73][74][75][71][72] |

| F1 | Southern Williams Bay to Como | Walworth | WI | 42.57°N 88.55°W | 21:50–? | 1.9 miles (3.1 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | This brief, small tornado may have begun at 4:34 p.m. CDT (21:34 UTC) and traveled 5 mi (8.0 km) before dissipating. It passed through the south side of Williams Bay and dissipated in Como. The tornado ripped the roofs off a few homes and a business but mostly produced minor damage to vegetation. One other home sustained severe damage. Losses totaled $250,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as a near-F4. | [76][77][55][78][62] |

| F1 | ESE of Lake Lorraine | Walworth | WI | 42.72°N 88.7°W | 21:55–? | 1 mile (1.6 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This short-lived tornado flattened a barn near Richmond. Losses totaled $25,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F2. Storm Data listed the touchdown as having occurred 2 1⁄2 mi (4.0 km) east of East Troy. | [79][80][75][78] |

| F1 | Geneva | Kane | IL | 41.88°N 88.3°W | 22:00–? | 0.3 miles (0.48 km) | 150 yards (140 m) | This tornado, first sighted from DuPage Airport, produced a 300-to-500-foot-wide (91 to 152 m) swath of damage. After crossing Illinois Route 38, the tornado damaged at least 12 homes, some of which lost their walls and roofs. Losses totaled $250,000. | [81][82][71][72] |

| F1 | Beach Park–Southern Zion | Lake | IL | 42.43°N 87.83°W | 22:04–? | 0.5 miles (0.80 km) | 250 yards (230 m) | This tornado occurred in association with the Crystal Lake–Gurnee supercell. A narrow funnel cloud briefly touched down and damaged two homes. Airplanes flipped at Waukegan National Airport—then called Waukegan Memorial Airport—and strong winds of 82 mph (132 km/h) damaged hangars. However, a downburst rather than the tornado may have caused the damage at the airport. Losses totaled $250,000. | [83][84][71][62][72] |

| F1 | SSW of Tunnel City | Monroe | WI | 43.97°N 90.58°W | 22:14–? | 2 miles (3.2 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | This tornado occurred west of Tomah. It destroyed several outbuildings on a farm, including barns and sheds. Losses totaled $25,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F2. | [85][86][78][75] |

| F3 | S of Hamlet to W of Dunlap | Starke, Marshall, St. Joseph, Elkhart | IN | 41.35°N 86.58°W | 22:45–? | 35.6 miles (57.3 km) | 250 yards (230 m) | 10 deaths – This was the first of four destructive tornadoes to affect Elkhart County, Indiana, and was the first member of a long-lived, destructive tornado family. As the narrow but well-defined tornado crossed Koontz Lake, it produced severe destruction and destroyed or damaged 100 cottages. Near La Paz, an Indiana state trooper on U.S. Route 31 photographed the tornado: a vivid white funnel, silhouetted by sunlight, against a backdrop of darkness. Outside La Paz, the tornado destroyed six homes and a church, as well as a high school being built then. The tornado then struck Wyatt, destroying 20 more homes before dissipating. 82 people were injured and losses totaled $75.250 million. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F4. | [87][88][89][90][91][92][93][75][94] |

| F4 | NW of Lamont to NNE of Courtland Township | Ottawa, Kent | MI | 43.02°N 85.92°W | 22:54–? | 20.6 miles (33.2 km) | 300 yards (270 m) | 5 deaths — Beginning over Ottawa County, this tornado destroyed only a few homes before entering Kent County. It then produced much more severe damage through the Comstock Park area, north of Grand Rapids, with 224 homes destroyed or damaged. The tornado also tracked through Rockford before dissipating. 142 people were injured and losses totaled $2.525 million. | [95][96][97][20][78][94] |

| F3 | N of Hebron to ENE of South Center | Porter, LaPorte | IN | 41.35°N 87.2°W | 23:10–? | 33.1 miles (53.3 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This was the first member of a long-lived, deadly tornado family that trailed the Koontz Lake–Wyatt storm. The tornado destroyed several homes and barns; six of the homes sustained borderline-F4-level damage. Significant damage occurred southwest of Wanatah and south of Kingsford Heights, but the path was quite narrow as it hit farmland. The tornado passed through South Wanatah as well. Losses totaled $50 million. Grazulis listed four injuries. | [98][99][100][93][75] |

| F4 | SW of Wakarusa to NW of Middlebury | St. Joseph, Elkhart | IN | 41.52°N 86.07°W | 23:15–? | 21.2 miles (34.1 km) | 33 yards (30 m) | 31 deaths – See section on this tornado – 252 people were injured and losses were unknown. Grazulis listed 14 deaths and 200 injuries. | [101][102][13][75][103][10][92] |

| F4 | S of Middlebury to SW of Greenfield Mills | Elkhart, LaGrange | IN | 41.62°N 85.7°W | 23:40–? | 21.6 miles (34.8 km) | 177 yards (162 m) | 5 deaths – This tornado, which formed while the preceding was still ongoing, may have begun as a waterspout over the Goshen Dam Pond, but it first produced damage farther afield. The tornado later produced "devastating" damage to the Rainbow Lake area, where 12 homes sustained high-end F4 damage and foundations were swept clean. The tornado also passed through Ontario and dissipated near Brighton. 41 people were injured and losses totaled $2.750 million. Unofficial estimates of the death toll vary, with Grazulis listing 19 deaths, 17 of which occurred south of Shipshewana. | [104][105][106][103][94][10] |

| F4 | Orland to SSE of West Sumpter, MI (1st tornado) | Steuben (IN), Branch (MI), Hillsdale (MI), Lenawee (MI), Monroe (MI), Washtenaw (MI) | IN, MI | 41.73°N 85.17°W | 00:00–? | 90.3 miles (145.3 km) | 1,760 yards (1,610 m) | 23 deaths – See section on this tornado – 294 people were injured. | [107][108][109][110][111][112][94][113][13][92][10][78] |

| F1 | SE of Burnips to ENE of Middleville | Allegan, Barry | MI | 42.72°N 85.83°W | 00:05–? | 19.5 miles (31.4 km) | 200 yards (180 m) | 1 death — This tornado or a related one may have begun as far southwest as Saugatuck, leaving debris in the city and causing damage north of Hamilton. Officially, damage began in the Burnips area and continued eastward through Dorr, leaving a trailer and five homes destroyed with 25 other "dwellings" damaged. One woman died in the trailer, and a few people were hospitalized due to severe injuries. Some reports indicated twin tornadoes along the path. Nine people were injured and losses totaled $500,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F2. | [114][115][116][93] |

| F4 | ENE of South Raub to NW of Middlefork | Tippecanoe, Clinton | IN | 40.33°N 86.83°W | 00:07–? | 21.8 miles (35.1 km) | 500 yards (460 m) | This was the first member of a fast-moving tornado family that tracked 273 mi (439 km) into Ohio, producing five or more violent tornadoes, and ended near Lake Erie. The tornado destroyed or damaged several homes and other buildings, but mostly at F2–F3 intensity. Some homes sustained F4-level damage near Cambria, in Mulberry, and in Moran. 44 people were injured and losses totaled $2 million. | [117][118][119][120][121][13] |

| F4 | NW of Woodland to ENE of Scott | St. Joseph, Elkhart, LaGrange | IN | 41.58°N 86.2°W | 00:10–? | 37 miles (60 km) | 333 yards (304 m) | 36 deaths – See section on this tornado – 321 people were injured and losses were unknown. | [122][123][124][125][126] |

| F4 | SE of Middlefork to SE of Arcana | Clinton, Howard, Grant | IN | 40.4°N 86.38°W | 00:20–? | 48 miles (77 km) | 880 yards (800 m) | 25 deaths – See section on this tornado – 835 people were injured and losses totaled $500.025 million. | [127][128][129][130] |

| F3 | W of Cooper Township to NE of Augusta | Kalamazoo | MI | 42.37°N 85.6°W | 00:30–? | 14.2 miles (22.9 km) | 150 yards (140 m) | A strong tornado moved east across the outskirts of Kalamazoo, destroying or damaging 26 homes and other structures. The tornado passed through Southern Richland. 17 people were injured and losses totaled $250,000. | [131][132] |

| F3 | Hastings to NNE of Woodbury | Barry, Eaton | MI | 42.65°N 85.3°W | 00:40–? | 14.1 miles (22.7 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This tornado struck the north side of Hastings and continued to near Woodland, destroying several barns and garages. 15 homes sustained damage as well. Five people were injured and losses totaled $250,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F2. | [133][134][120] |

| F4 | Kinderhook to SSE of West Sumpter (2nd tornado) | Branch, Hillsdale, Lenawee, Monroe, Washtenaw | MI | 41.8°N 85°W | 00:40–? | 80.5 miles (129.6 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | 21 deaths — See section on this tornado – 293 people were injured. | [135][136][137][138][139][94][113][13][92][10] |

| F4 | S of Crawfordsville to Southern Arcadia | Montgomery, Boone, Hamilton | IN | 40.02°N 86.87°W | 00:50–? | 45.7 miles (73.5 km) | 1,667 yards (1,524 m) | 28 deaths — An extremely large and violent tornado, up to 1 mi (1.6 km) wide, swept away homes as it passed just northwest and north of Lebanon. One person died in a destroyed home east of Crawfordsville, but 21 of the 28 deaths occurred in two areas near Lebanon and Sheridan. The tornado lofted two cars more than 100 yd (91 m), killing four occupants. In all, the tornado destroyed about 80 homes and injured 123 people. Losses totaled $75 million. A 1999 technical memorandum lists the tornado as an F5, though it is officially F4. | [140][141][142][143][120][126] |

| F4 | ESE of Roll to ESE of Venedocia, OH | Blackford (IN), Wells (IN), Adams (IN), Mercer (OH), Van Wert (OH) | IN, OH | 40.55°N 85.38°W | 01:10–? | 52.5 miles (84.5 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | 4 deaths — As the Greentown–Marion tornado dissipated, this tornado formed near Roll. On its long track across eastern Indiana and western Ohio, the tornado produced violent damage to three areas: in Keystone, with two deaths; in Linn Grove, with a few other deaths; and south of Willshire, Ohio, with two final deaths. Areas near Willshire sustained the most severe damage, with 10 homes destroyed and five flattened. In Berne, Indiana, the tornado cut a path through the northern part of the small city, damaging homes and businesses including a bowling alley, a grocery store, and a lumber yard before the supercell crossed into Ohio. Residents reported two tornadoes near Berne. 125 people were injured and losses totaled $52.750 million. | [144][145][146][147][148][149][120][10] |

| F4 | W of Dewitt to ENE of Laingsburg | Clinton, Shiawassee | MI | 42.85°N 84.65°W | 01:15–? | 21 miles (34 km) | 100 yards (91 m) | 1 death — This tornado killed one person in an obliterated home and destroyed about 10 other homes. Eight people were injured and losses totaled $500,000. | [150][151][152][120] |

| F2 | SW of Crystal to Southern Alma | Montcalm, Gratiot | MI | 43.25°N 84.93°W | 01:25–? | 15.1 miles (24.3 km) | 440 yards (400 m) | This tornado first destroyed some homes and barns in Crystal. It then hit many rural farms in its path, leveling farm buildings and killing or injuring livestock. The tornado passed through Sumner en route to Alma. One home near Alma was nearly flattened, and five other homes and barns were destroyed nearby. One person was injured and losses totaled $500,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F3. | [153][154][155][156] |

| F2 | E of Alma (1st tornado) | Gratiot | MI | 43.38°N 84.62°W | 01:30–? | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | This was one of four tornadoes to strike Alma with paths up to 1 mi (1.6 km) wide. The damage path may have begun near Vestaburg. The tornado caused damage to several buildings, including the library, which had its roof torn off. The tornado destroyed a telephone repair facility as well. Losses totaled $25,000. Grazulis listed a skipping path length of 10 mi (16 km). | [157][158][159] |

| F2 | E of Alma (2nd tornado) | Gratiot | MI | 43.38°N 84.62°W | 01:30–? | 0.5 miles (0.80 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | Losses totaled $25,000. Grazulis did not list the tornado as an F2 or stronger. | [160][161] |

| F2 | S of St. Louis | Gratiot | MI | 43.37°N 84.6°W | 01:30–? | 1 mile (1.6 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | Losses totaled $25,000. Grazulis did not list the tornado as an F2 or stronger. | [162][163] |

| F2 | SSE of Bay City | Bay | MI | 43.55°N 83.87°W | 01:50–? | 9.9 miles (15.9 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This tornado tore the roofs off homes and an automobile dealership. Trailers and barns were destroyed as well. Two people were injured and losses totaled $250,000. | [164][165][159] |

| F2 | ESE of Quanicassee to WSW of Unionville | Tuscola | MI | 43.57°N 83.63°W | 02:00–? | 9 miles (14 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This tornado damaged a fire station, which had its roof ripped off, and a lumberyard. The tornado also leveled barns. Downburst winds may have damaged the fire station in Unionville. Losses totaled $250,000. | [166][167][159] |

| F4 | N of Elida to WNW of Houcktown | Allen, Hancock | OH | 40.8°N 84.2°W | 02:30–? | 32.5 miles (52.3 km) | 400 yards (370 m) | 13 deaths — This tornado destroyed numerous homes and farms along the track, with severe damage in many spots. Two deaths occurred west of Cairo, but most of the deaths, five in all, took place south of Bluffton. 104 people were injured and losses totaled $2.750 million. | [168][169][170][159] |

| F4 | Northern Toledo to Lost Peninsula, MI | Lucas (OH), Monroe (MI) | OH, MI | 41.67°N 83.6°W | 02:30–? | 5.6 miles (9.0 km) | 200 yards (180 m) | 18 deaths – A tornado struck North Toledo with high-end F4 intensity. Five people were killed when a tornado flipped over a bus on the Detroit-Toledo Expressway (today's Interstate 75). About 50 homes in the northern suburbs of Toledo were completely destroyed, several of which were completely swept away. The tornado also hurled cars and boats against and onto buildings. A paint factory and department store were destroyed as well. Two people were killed on the Lost Peninsula in Michigan. There were reports of "glowing" twin funnels during the event—perhaps related to static electricity. 236 people were injured and losses totaled $27.5 million. | [171][172][173][20][159][174] |

| F4 | Fort Loramie to NW of Maplewood | Shelby | OH | 40.35°N 84.38°W | 03:00–? | 18.4 miles (29.6 km) | 300 yards (270 m) | 3 deaths — This tornado mostly affected rural areas but almost struck the communities of Anna, Swanders, and Maplewood. The tornado struck a train of 68 railcars near Swanders, lifting 53 from the railroad tracks. The tornado destroyed almost 25 homes, severely damaged 20 others, and lofted a car 200 yd (180 m). 50 people were injured and losses totaled $2.5 million. A satellite tornado may have formed just north of the main funnel and flipped a trailer, causing two injuries. | [175][176][159][177] |

| F3 | SE of Tiffin to ESE of Omar | Seneca | OH | 41.07°N 83.13°W | 03:15–? | 15 miles (24 km) | 300 yards (270 m) | 4 deaths — This tornado may have first touched down south of Alvada, but is first officially documented southeast of Tiffin. It then struck the rural community of Rockaway, leveling four homes and severely damaging three, with one death. 30 people were injured and losses totaled $250,000. Estimates of the death toll vary, with some sources listing only one death. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F4. | [178][179][174] |

| F4 | WSW of Pittsfield to Northern Strongsville | Lorain, Cuyahoga | OH | 41.23°N 82.25°W | 04:05–? | 22 miles (35 km) | 400 yards (370 m) | 18 deaths – See section on this tornado – 200 people were injured and losses totaled $50 million. | [180][181][182][10][183][184][13][174][22] |

| F1 | Southern Eaton | Preble | OH | 39.73°N 84.63°W | 04:15–? | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | A brief tornado uplifted a roof from a building at a livestock producer. Losses totaled $25,000. | [185][186][177] |

| F1 | WSW of Brunswick to ENE of Hinckley | Medina | OH | 41.23°N 81.87°W | 04:30–? | 8.2 miles (13.2 km) | 200 yards (180 m) | This tornado hit the town of Brunswick, destroying a home and badly damaging many others. Six people were injured and losses totaled $250,000. The tornado may have ended north of Richfield. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F3 with a path ending north of Richfield in Summit County. | [187][188][174] |

| F2 | NNW of Magnetic Springs to N of Fulton | Union, Delaware, Morrow | OH | 40.37°N 83.27°W | 04:30–? | 22.2 miles (35.7 km) | 400 yards (370 m) | 4 deaths — This tornado struck the communities of Radnor and Westfield, causing three deaths in the former, and destroyed nearly 25 homes along its path. The tornado injured 62 people; 20 or more of the injured were in Westfield. Losses totaled $5.025 million. One of the official deaths may have been from a heart attack and thus only indirectly related to the tornado. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F3. | [189][190][191][192][174] |

| F1 | SSE of Cedarville | Greene | OH | 39.73°N 83.8°W | 04:50–? | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | This weak and brief tornado produced minimal damage to trees and roofs. Losses totaled $25,000. | [193][194][177] |

April 12 event

| F# | Location | County / Parish | State | Start coord. |

Time (UTC) | Path length | Max. width | Summary | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | WNW of South Bloomfield to N of Somerset | Pickaway, Fairfield, Perry | OH | 39.73°N 83.03°W | 05:30–? | 38.4 miles (61.8 km) | 300 yards (270 m) | This tornado initially produced negligible damage, but then leveled many farm buildings after passing the Scioto River. The tornado caused most of its damage to farms north of Lancaster in an 8-mile-long (13 km) swath. The tornado then struck and destroyed 12 trailers in Dumontville before dissipating. 13 people were injured and losses totaled $750,000. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F2. | [195][196][197][198][174] |

| F1 | Cadiz | Harrison | OH | 40.27°N 81°W | 06:01–? | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | A brief tornado partially destroyed the roofs of two buildings and left other minor damage. One person was injured and losses totaled $2,500. | [199][200][177] |

| F1 | W of Grassdale | Bartow | GA | 34.27°N 84.8°W | 09:50–? | 2 miles (3.2 km) | 50 yards (46 m) | A brief tornado snapped or uprooted trees. Losses totaled $2,500. | [201][202][35] |

| F2 | ENE of Kegley | Mercer | WV | 37.4°N 81.1°W | 11:30–? | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | 10 yards (9.1 m) | A short-lived tornado removed a metal garage roof. Losses totaled $2,500. Grazulis did not list the tornado as an F2 or stronger. | [203][204][61] |

Lakewood–Crystal Lake–Burtons Bridge–Island Lake, Illinois

| F4 tornado | |

|---|---|

Richard, Rosalie, and John Holter died two blocks from the foundation of their home in Crystal Lake. A truck landed on the empty foundation. | |

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Damage | $1.5 million (1965 USD) |

| Casualties | 6 fatalities, 75 injuries |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

This devastating tornado was first detected at 4:27 p.m. CDT (21:27 UTC), but officially touched down seven minutes earlier, in Lakewood. At that time the tornado first produced visible damage, at the Crystal Lake Country Club; two firs on the golf course were prostrated. Initially narrow, the tornado subsequently and rapidly widened to 1,300 ft (400 m; 0.40 km). Crossing Nash Street and McHenry Avenue in Crystal Lake, the tornado unroofed or severely damaged several houses. Alongside U.S. Route 14 the tornado claimed its first fatality, a man in a barn. Nearby gas stations and a strip mall were damaged. At the latter place, a roof sheltering a Piggly Wiggly and a Neisner's collapsed, trapping 20 or more people below. The tornado tossed cars about in the parking lot as well. Shortly afterward, the tornado struck the Colby subdivision, destroying or severely damaging 155 homes. F4-level damage occurred as several homes were completely swept off their foundations. Four deaths occurred in the neighborhood, including three in one family whose home was obliterated. Their bodies were located two blocks distant and a pickup truck was found to have landed in the basement. The tornado scattered debris from the Colby subdivision up to 1⁄2 mi (0.80 km) away.

After ravaging the Colby neighborhood, the tornado destroyed a number of warehouses and shattered windows. A diesel plant, a wallpaper factory, and a manufacturer sustained damage ranging from light to heavy. The tornado then extensively damaged the Orchard Acres subdivision, crossed Illinois Route 31, and apparently weakened before impacting farmland. A few barns and isolated trees were damaged. The tornado may have dissipated and reformed as a new tornado near the Fox River. The tornado also struck the community of Burtons Bridge. The tornado, now 500 to 800 yd (460 to 730 m) wide, then restrengthened and felled mature oak trees as it crested a precipitous hill before striking Bay View Beach. There the tornado badly damaged a number of homes and downed willow trees. Finally, the tornado intersected Illinois Route 176 and produced its final swath of significant damage in Island Lake. In Island Lake the tornado tossed boats ashore, wrecked piers, and caused homes to collapse, resulting in one additional death. The tornado also displaced several homes from their foundations. The tornado neared U.S. Route 12 as it dissipated at 3:42 p.m. CST (21:42 UTC). Damage estimates were set at about $1.5 million.[205]

Midway, Indiana

| F4 tornado | |

|---|---|

The remains of the Midway Trailer Court in Midway, Indiana, following the F4 tornado of April 11, 1965. | |

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Casualties | 31 fatalities, 252 injuries |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

This was the most famous and well-publicized of the Palm Sunday tornadoes, often remembered as the first of two F4 tornadoes to hit the Dunlap (Elkhart)–Goshen area. It formed near the St. Joseph–Elkhart County border and tracked northeastward, striking Wakarusa, where it caused severe damage and killed a child. The tornado then intensified significantly as it moved toward northern Goshen and the Midway Trailer Court. As it neared the trailer park, Elkhart Truth reporter Paul Huffman, then reporting on severe weather, overheard a report of a tornado approaching his position on U.S. Route 33, about 1 mi (1.6 km) south of Midway. As Huffman awaited the storm, he noticed the tornado approaching from the southwest, so he began taking a series of photographs, six in all. The photographs captured the evolution of the storm into twin funnels as it struck the trailer park, with each funnel gyrating around a central point yet only producing one damage swath. The tornado struck the trailer park at 6:32 p.m. CDT (23:32 UTC). (Roughly 45 minutes later, another F4 tornado passed just to the north of the Midway Trailer Court, splitting into yet another pair of funnels as it struck the Sunnyside neighborhood in Dunlap.) The tornado obliterated roughly 80% of the trailer park, with 10 deaths, and caused F4 damage to numerous other homes near Middlebury, some of which were swept clean. Three more people died in the Middlebury area before the tornado ended. While officially considered one tornado, recent studies indicate that the event consisted of two tornadoes and was not a multiple-vortex event. Unofficial estimates of the death toll vary, with Grazulis listing 14 deaths instead of the 31 appearing in the official National Climatic Data Center/National Centers for Environmental Information (NCDC/NCEI) database. An airplane wing from Goshen Airport was found 35 mi (56 km) distant, in Centreville, Michigan.[206]

Coldwater Lake–Southern Hillsdale–Manitou Beach–Devils Lake–Southern Tecumseh, Michigan (two tornadoes)

Destruction in the Manitou Beach–Devils Lake area after the F4 tornadoes of April 11, 1965 | |

| Tornadoes confirmed | 2 |

|---|---|

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Damage | $32 million (1965 USD) |

| Casualties | 44 fatalities, 587 injuries |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

With the telephone lines down, emergency services in Elkhart County, Indiana, could not warn Michigan residents that the tornadoes were headed their way. From the Detroit Metropolitan Airport, the radar operator at the U.S. Weather Bureau Office (WBO) observed that the thunderstorms over Northern Indiana and western Lower Michigan were moving east-northeastward at 70 mph (110 km/h). Of the southernmost counties of Michigan, all but three—Berrien, Cass, and St. Joseph—were hit.

Starting just south of the Indiana-Michigan state line, near Orland, the first, deadliest, and strongest of two massive tornadoes, each rated F4, debarked trees and leveled homes on the shoreline of Lake Pleasant in Steuben County. Crossing into Branch County, Michigan, the tornado damaged more homes in East Gilead. The tornado was up to 1 mi (1.6 km) as it obliterated homes on Coldwater Lake; 18 deaths occurred there. Debris from the empty foundations was strewn over the surface of the lake and deposited in a small cove. The tornado destroyed 200 homes and caused one additional death as it traversed Branch County. After striking Coldwater Lake, the tornado widened even further, up to 2 mi (3.2 km) across, destroying a century-old farmhouse and killing a family of six near Reading. The tornado then narrowed back to 1 mi (1.6 km) as it struck Baw Beese Lake, near the southern edge of Hillsdale. The tornado hurled a New York Central Railroad freight train into Baw Beese Lake. Across Hillsdale County the tornado killed 11 or more people and destroyed 177 homes.

Entering Lenawee County, the tornado traversed the Irish Hills and approached Manitou Beach–Devils Lake. As it struck Manitou Beach–Devils Lake, the tornado destroyed the Manitou Beach Baptist Church; of the 50 people then in attendance for Palm Sunday services, 26 failed to reach shelter in time and were stranded beneath debris for up to two hours. Eight fatalities occurred in the church. The local dance pavilion on Devils Lake was demolished, having recently been rebuilt after a fire on Labor Day in 1963. One of the tornadoes damaged parts of Onsted; in the nearby village of Tipton, which suffered a direct hit, 94% of the town's buildings were damaged or destroyed. Across Lenawee County the tornado destroyed 189 homes. About 30 minutes later, the Manitou Beach–Devils Lake area in Lenawee County was hit by the second of the two tornadoes, causing numerous fatalities, including a family of six in eastern Lenawee County. Many homes were hit twice.

One or both F4 tornadoes struck the then-Village of Milan, south of Ann Arbor. The Wolverine Plastics building on the Monroe County side of town, then the top employer in the village, was destroyed with the roof being completely removed in the process. The Milan Junior High School was seriously damaged along with the adjacent, senior high school, disused since 1958, at Hurd and North streets, on the Washtenaw County side of Milan. Milan became a city in 1967; opened a new Middle School in 1969, which replaced the old Junior High School; and eventually demolished the 1900 building that housed the former junior and senior high schools.

The first of the F4 tornadoes produced a 151-mile-per-hour (243 km/h) wind gust at Tecumseh—the highest wind measurement in a tornado until a measurement of 276 mph (444 km/h) near Red Rock, Oklahoma, on April 26, 1991; a higher measurement of 318 mph (512 km/h)—later corrected to 307 mph (494 km/h)—in the F5 tornado of May 3, 1999, broke this record. Damage from the two tornadoes was difficult to separate and covered more than 2 to 4 mi (3.2 to 6.4 km) across, including much downburst and microburst destruction. Total damage estimates from the two tornadoes were $32 million with more than 550 homes, a church, and 100 cottages destroyed.[207]

Southern Elkhart–Dunlap, Indiana

| F4 tornado | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of the Sunnyside subdivision in Dunlap, Indiana, after the F4 tornado of April 11, 1965. | |

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Casualties | 36 fatalities, 321 injuries |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

This was the second and deadliest of two violent tornadoes to strike the Elkhart–Goshen area, with the highest single-tornado death toll in the outbreak. It hit Dunlap about an hour after another F4 tornado hit the Midway trailer park a short distance to the southeast. Few people received warning due to the passage of the earlier storm, which disrupted communications and downed power lines, thereby affecting rescue efforts after the earlier tornado as well. The Dunlap tornado first produced tree damage beginning just west of State Road 331. Prior to crossing the St. Joseph–Elkhart county line, the tornado claimed its first two fatalities. As the tornado neared Dunlap, it intensified into an extremely violent tornado. It then devastated the Sunnyside Housing addition and the unoccupied Sunnyside Mennonite Church. The Sunnyside subdivision was completely destroyed, with many homes swept away. The Kingston Heights subdivision was similarly devastated. The death toll from the two subdivisions was 28 people, with another six killed in a home and truck stop at the junction of State Road 15 and U.S. Route 20. The Palm Sunday Tornado Memorial Park now exists near this location, at the corner of County Road 45 and Cole Street in Dunlap. After striking Dunlap, the tornado apparently weakened somewhat, but still generated extensive damage eastward to Hunter Lake. Shortly before dissipating, the tornado tossed cars off the Indiana Turnpike near Scott. Like the Midway tornado, the Dunlap event was also was witnessed as twin funnels: a photographer standing amidst the wreckage of the Midway Trailer Court captured the Dunlap tornado as it passed just to the north. It may have been the strongest tornado on April 11; in fact, Grazulis and other sources have assigned an F5 rating to the tornado, though it is officially rated F4.[208]

Russiaville–Alto–Southern Kokomo–Greentown, Indiana

| F4 tornado | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Alto, Indiana, following the F4 tornado of April 11, 1965. | |

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Damage | $500.025 million (1965 USD) |

| Casualties | 25 fatalities, 835 injuries |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

As the Lafayette–Middlefork tornado dissipated, a new tornado developed nearby without a definite break in the damage path. Due to changes in the intensity of the damage, surveyors split the path into two separate tornadoes. At about 7:28 p.m. CDT (00:28 UTC), the new, rapidly strengthening tornado hit Russiaville, causing severe damage to the entire community. The 3⁄4-mile-wide (1.2 km) tornado destroyed or damaged 90% of the community, though most of the damage ranged from F0–F3. The tornado then widened to 1 mi (1.6 km) across as it moved into nearby Alto, causing F4-level damage to homes, before striking the southern edge of the larger city of Kokomo. Collectively, the tornado destroyed 100 homes in Alto and Kokomo. The Maple Crest apartment complex was unroofed and incurred the collapse of its uppermost walls. As the tornado continued eastward, it apparently intensified and killed ten people in Greentown, most of whom had been riding in automobiles that the tornado hurled across the landscape. The tornado destroyed 80 homes, many of which it obliterated and swept away, as it stuck multiple subdivisions in the Greentown area. In all, the tornado killed 18 people and injured another 600 in Howard County alone. Just south of Swayzee, the tornado leveled some more homes and caused three additional deaths. As it struck the southern outskirts of Marion, the tornado leveled a pair of homes, partly unroofed a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital, and wrecked the Panorama shopping center. 20 injuries occurred at the VA hospital, and looters scavenged the shopping center. Several homes were destroyed and hundreds others damaged in Marion as well. The tornado killed five people as it traversed Grant County. Losses totaled $500.025 million, $12 million alone of which occurred near Marion.[209]

Pittsfield–Grafton–Strongsville, Ohio

| F4 tornado | |

|---|---|

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Damage | $50 million (1965 USD) |

| Casualties | 18 fatalities, 200 injuries |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

Shortly after 11:00 p.m. CDT (04:00 UTC), a tornado touched down in Lorain County, Ohio, and headed east-northeastward. Around 11:12 p.m. CDT (04:12 UTC), the 1⁄4-mile-wide (0.40 km) tornado struck Pittsfield, Ohio, then located at the junction of Ohio State Route 303 and Ohio State Road 58. Of the settlement's 50 residents, the tornado killed seven. The tornado also killed two motorists whose arrival in town coincided with the tornado's. According to the U.S. Weather Bureau Office (WBO) in Cleveland, Ohio, the tornado produced "total" devastation as it struck Pittsfield. The tornado destroyed 12 homes, six of which "literally vanished," along with a combined gas station/grocery store, a pair of churches, and the town hall. The tornado also toppled a statue at a Civil War monument, but the concrete base of the statue remained standing.

After ravaging Pittsfield, the tornado damaged 200 homes in and near Grafton, some of which indicated F2-level intensity. A total of 17 homes were severely damaged in nearby LaGrange and Columbia Station. As the tornado reached the Cleveland metropolitan area, it diverged into two paths about a 1⁄2 mi (0.80 km) apart. Several witnesses also saw two funnels merging into one, similar to the Midway–Dunlap tornadoes. Large trees situated 50 ft (15 m) apart were found to have been felled in opposite directions. The tornado displayed borderline-F5-level damage in northernmost Strongsville. There, 18 homes were leveled, some of which were cleanly swept from their foundations, and 50 others were severely damaged in town. Damages amounted to at least $5 million and are officially listed as $50 million. Grazulis classified the tornado as an F5, but it is officially rated F4.[210]

Non-tornadic effects

A vigorous, pre-frontal squall line generated severe thunderstorm winds from eastern Iowa to lakefront Illinois. Winds peaked at 70 kn (81 mph; 130 km/h) in Dixon, Illinois, and an anemometer at O'Hare International Airport in Chicago registered 60 kn (69 mph; 110 km/h). The strong winds, coupled with hail, damaged or destroyed numerous structures, felled trees, and downed utility wires. Across Northern Illinois, numerous funnel clouds were sighted in Wheaton, Carol Stream, Winfield, West Chicago, Aurora, and Rockford, respectively. Thunderstorms also generated hail of up to 2 in (5.1 cm) in diameter as well; 2-inch-diameter (5.1 cm) measurements occurred from South Dakota, Oklahoma, and Arkansas to Indiana, Mississippi, and Georgia on April 10–12.[3][78]

Aftermath and recovery

In the Midwest, at least 266 people—some sources say 256–271—were killed and 1,500 injured (1,200 in Indiana). This is the fourth-deadliest day for tornadoes on record, trailing April 3, 1974 (310 deaths), the April 27, 2011 (324), and March 18, 1925 (747, including 695 by the Tri-State Tornado).[211][11][17][212] It occurred on Palm Sunday, an important day in the Christian religion, and many people were attending services at church, one possible reason why some warnings were not received. There had been a late winter in 1965, much of March being cold and snowy; and as the day progressed, warm temperatures encouraged picnickers and sightseers. For many areas, April 11 marked the first day of above-average temperatures, so members of the public, being outdoors or attending services, failed to receive updates from radio and television.[11][13][23][213] The high death toll in the outbreak despite accurate warnings led to changes in the dissemination of severe weather alerts by the Severe Local Storm Warning Center in Kansas City, Missouri, now the Norman, Oklahoma-based Storm Prediction Center.[17] The U.S. Weather Bureau investigated the large number of deaths. Although weather-radar stations were few and far between in 1965, the severe nature of the thunderstorms was identified with adequate time to disseminate warnings. But the warning system failed as the public never received them. Additionally, the public did not know the difference between a Forecast and an Alert. Thus the terms tornado watch and tornado warning were implemented in 1966.[214] Pivotal to those clarifications was a meeting in the WMT Station's studio in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Officials of the severe storms forecast center in Kansas City met with WMT meteorologist Conrad Johnson and News Director Grant Price. Their discussion led to establishment of the official "watch" and "warning" procedures in use since 1966. Additionally, communities began activating civil defense sirens during tornado warnings, and storm spotting via amateur radio networks and other media received increased logistical support and emphasis, leading to the eventual creation of SKYWARN.[23][214][213]

Oddities/records

Additionally, significant scientific data were gathered from aerial surveys of the tornado paths. The outbreak was the first to be studied in-depth aerially by tornado scientist Tetsuya Theodore Fujita, who proposed new theories about the structure of tornadoes based upon his study. Dr. Fujita discovered suction vortices during the Palm Sunday tornado outbreak. It had previously been thought the reason why tornadoes could hit one house and leave another across the street completely unscathed was because the tornado would "jump" from one house to another. However, Fujita discovered that the actual reason is most destruction is caused by suction vortices: small, intense mini-tornadoes within the main tornado.[215]

The tornado outbreak generated 38 significant tornadoes, 18 of them violent—F4 or F5 on the Fujita scale of tornado intensity—and 22 deadly. Covering six states and about 335 sq mi (870 km2), the outbreak killed 266 people and became the deadliest to hit the United States since 1936, although more recently the 1974 and 2011 Super Outbreaks claimed that distinction. The 17 violent tornadoes on April 11, 1965, set a 24-hour record that stood until the first Super Outbreak produced 30 in 1974.[216] With 137 people killed and 1,200 injured in Indiana alone, the outbreak set a 24-hour record for tornado deaths in that state.

An unusually pronounced elevated mixed layer (EML) was present over the Great Lakes region during the outbreak—a similar pattern having been observed on March 28, 1920, April 3, 1956, and April 3, 1974. A strong jet stream, combined with tornadoes, lofted topsoil from Illinois and Missouri eastward, producing hazy skies prior to the arrival of storms.[10][13]

See also

- Lists of tornadoes and tornado outbreaks

- Tornado outbreak sequence of April 2–3, 1956 – Produced a powerful F5 tornado family in Michigan

- 1920 Palm Sunday tornado outbreak – Generated deadly F4 tornadoes in the Great Lakes region

- 1994 Palm Sunday tornado outbreak – Yielded long-tracked, intense tornadoes from Alabama to the Carolinas

- 1974 Super Outbreak – Associated with numerous violent tornadoes across much of Indiana and Greater Cincinnati

Notes

- All losses are in 1965 USD unless otherwise noted.

- An outbreak is generally defined as a group of at least six tornadoes (the number sometimes varies slightly according to local climatology) with no more than a six-hour gap between individual tornadoes. An outbreak sequence, prior to (after) the start of modern records in 1950, is defined as a period of no more than two (one) consecutive days without at least one significant (F2 or stronger) tornado.[5][6][7][8][9]

- This was known as a Severe Weather Forecast at the time.[17]

- At the time tornado watches were called tornado forecasts; SELS only began using the former terminology in 1966, after the Palm Sunday event. Respondents to a post-event survey noted that they confused tornado warnings with tornado forecasts; in turn, this contributed to the high death toll on April 11–12.[19][20][21][22]

- All dates are based on the local time zone where the tornado touched down; however, all times are in Coordinated Universal Time and dates are split at midnight CST/CDT for consistency.

- Prior to 1994, only the average widths of tornado paths were officially listed.[26]

References

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: Maps and Statistics. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Events reported between 04/10/1965 and 04/12/1965 (3 days). Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Events reported between 04/10/1965 and 04/12/1965 (3 days). Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Events reported between 04/10/1965 and 04/12/1965 (3 days). Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Schneider, Russell S.; Brooks, Harold E.; Schaefer, Joseph T. (2004). Tornado Outbreak Day Sequences: Historic Events and Climatology (1875-2003) (PDF). 22nd Conference on Severe Local Storms. Hyannis, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Hagemeyer, Bartlett C. (September 1997). "Peninsular Florida Tornado Outbreaks". Weather and Forecasting. Boston: American Meteorological Society. 12 (3): 400. Bibcode:1997WtFor..12..399H. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1997)012<0399:PFTO>2.0.CO;2.

- Hagemeyer 1997, p. 401

- Hagemeyer, Bartlett C.; Spratt, Scott M. (2002). Written at Melbourne, Florida. Thirty Years After Hurricane Agnes: the Forgotten Florida Tornado Disaster (PDF). 25th Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology. San Diego, California: American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (2001). The Tornado: Nature's Ultimate Windstorm. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-8061-3538-0.

- Blake Naftel; Jon Chamberlain; Becky Monroe; Ed Lacey Jr.; Dick Loney (2015). "April 11th 1965 Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak". Northern Indiana Weather Forecast Office. Syracuse, Indiana: National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Deedler, William R. (April 2015) [2005]. "Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak April 11th, 1965". Detroit/Pontiac, MI Weather Forecast Office. White Lake, Michigan: National Weather Service. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Fujita, T. T.; Bradbury, D. L.; Thullenar, C. L. (January 1970). Written at Chicago. "Palm Sunday tornadoes of April 11, 1965" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Boston: American Meteorological Society. 98 (1): 30–1. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1970)098<0029:PSTOA>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Naftel, Blake (3 April 2005). "The Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak - April 11, 1965". The Palm Sunday Outbreak. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University. Archived from the original on 8 April 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- P. H. Kutschenreuter, R. Fox (1965). "Annex 2". Written at Kansas City, Missouri. Report of Palm Sunday tornadoes of 1965 (PDF). NWS Service Assessments (Report). Natural Disaster Survey Report. Washington, D.C.: National Weather Service. p. 1. Retrieved 16 December 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Fujita & Bradbury 1970, p. 52

- Fujita & Bradbury 1970, p. 33

- Heidorn, Keith C. (14 September 2010) [2007]. "1965 Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak Part I: The Beginning". The Weather Doctor. Valemount, British Columbia: Islandnet.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Kutschenreuter & Fox 1965, p. 2, Annex 2

- Kutschenreuter & Fox 1965, p. 6

- "The Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak of 1965 in West Michigan". Grand Rapids, MI Weather Forecast Office. Grand Rapids, Michigan: National Weather Service. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Grazulis 2001, p. 91

- Heidorn, Keith C. (14 September 2010) [2007]. "1965 Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak Part III: Last Strikes and Aftermath". The Weather Doctor. Valemount, British Columbia: Islandnet.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Eagan, Shane (April 2015). "50th Anniversary of the 1965 Palm Sunday Outbreak". Chicago, IL Weather Forecast Office. Romeoville, Illinois: National Weather Service. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Kutschenreuter & Fox 1965, p. 6, Annex 2

- E. S. Epstein, G. A. Petersen, H. Lieb, J. Davies, V. Oliver, J. Purdom, P. Dales (December 1974). "Production". Written at Rockville, Maryland. The Widespread Tornado Outbreak of April 3-4, 1974: A Report to the Administrator (PDF). NWS Service Assessments (Report). Natural Disaster Survey Report. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Commerce. p. 18. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

...warning offices issued 'blanket' warnings because they knew severe storms were in the area, although they did not know the exact location, extent, and movement of the storms.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Brooks, Harold E. (April 2004). "On the Relationship of Tornado Path Length and Width to Intensity". Weather and Forecasting. Boston: American Meteorological Society. 19 (2): 310. Bibcode:2004WtFor..19..310B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2004)019<0310:OTROTP>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650410.29.7. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- U.S. Weather Bureau (April 1965). "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena". Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 7 (4): 27. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Kansas Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650410.20.4. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (July 1993). Significant Tornadoes 1680–1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. p. 1061. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- Storm Data 1965, p. 25

- Storm Data 1965, p. 27

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650410.29.9. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650410.29.10. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650410.29.11. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Arkansas Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650410.5.17. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Missouri Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650410.29.12. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Oklahoma Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.40.19. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Grazulis 1993, pp. 1061–72

- Storm Data 1965, p. 31

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Iowa Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Iowa Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.19.1. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Grazulis 1993, p. 1062

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Iowa Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.19.2. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Wisconsin Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Wisconsin Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.55.1. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Storm Data 1965, p. 34

- Fujita & Bradbury 1970, pp. 33–4

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Wisconsin Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.55.2. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Wisconsin Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.55.3. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Illinois Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Illinois Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.17.2. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- "1965 Palm Sunday Tornado". Crystal Lake Historical Society. Crystal Lake, Illinois: Crystal Lake Historical Society. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Storm Data 1965, p. 36

- Allsopp, Jim (Spring 2005). "40th anniversary of the Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak". NWS Chicago Newsletter. Romeoville, Illinois: National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Illinois Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.17.3. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Grazulis 1993, p. 1063

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Wisconsin Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.55.4. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Storm Data 1965, p. 35

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Wisconsin Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.55.5. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Illinois Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.17.4. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Illinois Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.17.5. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Wisconsin Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.55.6. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.18.7. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Heidorn, Keith C. (14 September 2010) [2007]. "1965 Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak Part II: Sunday Evening". The Weather Doctor. Valemount, British Columbia: Islandnet.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Fujita & Bradbury 1970, pp. 36–7

- Grazulis 1993, p. 1065

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.26.1. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.18.8. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.18.9. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Fujita & Bradbury 1970, p. 38

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.18.10. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.18.11. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Fujita & Bradbury 1970, pp. 38–9

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Michigan Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.26.3. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- National Weather Service (30 September 2019). Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (eds.). Tornado History Project: 19650411.18.12. Tornado History Project (Report). The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Grazulis 1993, p. 1066

- Fujita & Bradbury 1970, p. 40

- National Weather Service (August 2020). Indiana Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 14 October 2020.