Recreational dive sites

Recreational dive sites are specific places that recreational scuba divers go to enjoy the underwater environment. They include recreational diver training sites and technical diving sites beyond the range generally accepted for recreational diving. In this context all diving done for recreational purposes is included. Professional diving tends to be done where the job is, and with the exception of the recreational diving service industry, does not generally occur at specific sites chosen for their easy access, pleasant conditions or interesting features.

Recreational dive sites may be found in a wide range of bodies of water, and may be popular for various reasons, including accessibility, biodiversity, spectacular topography, historical interest and artifacts (such as shipwrecks), and water clarity. Tropical waters of high biodiversity and colourful sea life are popular recreational diving vacation destinations. South-east Asia, the Caribbean islands, the Red Sea and the Great Barrier Reef of Australia are regions where the clear, warm, waters and colourful and diverse sea life have made recreational diving an economically important tourist industry.

Recreational divers may accept a relatively high level of risk to dive at a site perceived to be of special interest. Wreck diving and cave diving have their adherents, and enthusiasts will endure considerable hardship, risk and expense to visit caves and wrecks where few have been before. Some sites are popular almost exclusively for their convenience for training and practice of skills, such as flooded quarries. They are generally found where more interesting and pleasant diving is not locally available, or may only be accessible when weather or water conditions permit.

Dive site

The term dive site is used differently depending on context. In professional diving in some regions it may refer to the surface worksite from which the diving operation is supported and controlled by the diving supervisor. This may alternatively be called the diving operation control site, dive base, or control point. The professional dive site may also legally include the underwater work site and the area between the surface control area and underwater work site.[1][2][3][4][5] In recreational diving it generally refers to the underwater environment of a dive. Where a site is named, it generally refers to the locality around a specific feature, which may be reasonably conveniently visited during a dive centred or focused on that feature. Conventions may vary regionally. In some places a named dive site may refer to a specific route with a given starting point, in others it may refer more loosely to a larger region which is far bigger than a diver could reasonably visit on dives with a common point.[6] Such regions may later be specified in more detail as they become better known, and what was originally referred to a single site may become several sites when they are described. Where a site is named for a shipwreck, it generally refers to the known extent of the wreckage, regardless of size. Synonyms include dive spot, dive location and diving site.

Names of sites

Names for the sites themselves range from descriptive through quixotic to pretentious, as they are chosen at the whim of whoever dives there and names the site. There is often no standardisation, and the same site may be known by different names to different divers. Few sites are reliably mapped or have a published description with an accurate position, and many of these are caves or wrecks of identified ships.

Rating of sites

Sites are generally rated by people who do not have an exhaustive experience of the full range of sites throughout the world, and preferences differ. It is unlikely that any published ratings are unbiased. Conditions at most sites vary from day to day, often considerably, depending on various factors, particularly recent weather.

Bodies of water commonly used for recreational diving

- Sea and Ocean shorelines and shoals. These are salt water sites and may support high biodiversity of plant and animal life forms. Shipwrecks are also common on some coasts, and are very popular attractions for a large number of divers.

- Lakes, usually containing fresh water. Large lakes have many features of seas including wrecks and a variety of aquatic life. Artificial lakes, such as clay pits, gravel pits, and quarries often have lower visibility. Some lakes are at high altitude and may require special considerations for altitude diving.

- Abandoned and flooded quarries are popular in inland areas for diver training and sometimes also recreational diving. Rock quarries may have reasonable underwater visibility if there is not so much mud or silt to cause low visibility. As they are not natural environments and usually privately owned, quarries often contain features intentionally placed for divers to explore, such as sunken boats, automobiles, aircraft, and abandoned machinery and structures. Flooded mines may provide the equivalent of flooded caves with an overhead environment, though generally with a known extent.

- Rivers generally contain fresh water but are often shallow and murky and may have strong currents.

- Caves containing water provide exotic and interesting, though relatively hazardous, opportunities for exploration.

Popular features of dive sites

There are a wide range of underwater features which may contribute to the popularity of a dive site:

- Accessibility is important, but not critical. Some divers will travel long distances at considerable cost to get to a site with exceptional features.

- Biodiversity at the site: Popular examples are coral, sponges, fish, sting rays, molluscs, cetaceans, seals, sharks and crustaceans.

- The Topography of the site: Coral reefs, walls (underwater cliffs), rocky reefs, gullies, caves, overhangs and swim-throughs (short tunnels or arches) can be spectacular. Terminology for the topography of dive sites is generally consistent with oceanographic practice, with occasional more eccentric usage.

- Historical or cultural items at the site: Shipwrecks, sunken aircraft and archaeological sites, apart from their historical value, form artificial habitats for marine life making them more attractive as dive sites.

- Underwater visibility: This can vary widely between sites and with time and other conditions. Poor visibility is caused by suspended particles in the water, such as mud, silt, suspended organic matter and plankton. Currents and surge can stir up the particles. Rainfall runoff can carry particulate matter from the shore. Diving close to the sediments on the bottom can result in the particles being kicked up by the divers fins. Sites which generally have good visibility are preferred, but poor visibility will often be tolerated if the site is sufficiently attractive for other reasons.

- Water temperature: Warm water diving is comfortable and convenient, and requires less equipment. Although cold water is uncomfortable and can cause hypothermia it can be interesting because different species of underwater life thrive in cold conditions.

- Currents and tidal flows can transport nutrients to underwater environments increasing the variety and density of life at a site. Currents can also be dangerous to divers as they can carry the diver being away from the surface support or the planned exit point. Currents that flow over large obstructions can cause strong local vertical currents and turbulence that are dangerous because they may cause the diver to lose buoyancy control risking barotrauma, or impact against the bottom terrain.

Regions where recreational diving is a major tourist industry

- Great Barrier Reef of Australia

- Apo Island in the Philippines

Regions of notable biodiversity

Temperate

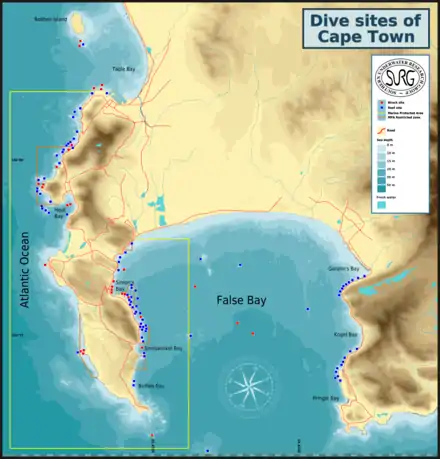

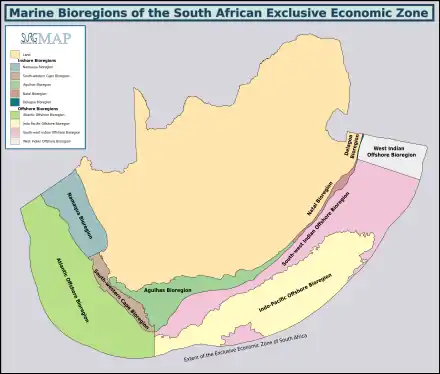

The Table Mountain National Park Marine Protected Area around the Cape Peninsula is a popular diving region in the Atlantic Ocean, in the vicinity of Cape Town, South Africa, with more than 250 named dive sites, many of which have been surveyed and mapped. The Cape Peninsula marks the boundary between the cool temperate Benguela ecoregion, which extends from Namibia to Cape Point, and is dominated by the cold Benguela Current, and the warm temperate Agulhas ecoregion to the east of Cape Point which extends eastwards to the Mbashe River. The break at Cape Point is very distinct in the inshore depth ranges, and the waters of the east and west sides of the peninsula support noticeably different ecologies, though there is a significant overlap of resident organisms. There are a large proportion of species endemic to South Africa along this coastline.[7][8][9]

Tropical

- Great Barrier Reef

- Indonesia

- The Red Sea

- Caribbean Sea

- The iSimangaliso Marine Protected Area is a coastal and offshore marine protected area in KwaZulu-Natal from the South Africa-Mozambique border in the north to Cape St Lucia lighthouse in the south.[10] There is a diving resort area serving this MPA at Sodwana Bay.

The MPA is in the tropical Delagoa ecoregion in the north of kwaZulu-Natal, which extends from Cape Vidal northwards into Mozambique. There are some species endemic to South Africa along this coastline, but most of the species are tropical Indo-Pacific.[9]

Dive sites of unique or exceptional interest

Wreck dive sites

| Vessel Name | Position | Location | Country/Territory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolphus Busch | Looe Key, Florida | United States | |

| USS Arthur W. Radford | Cape May, New Jersey | United States | |

| HMAS Adelaide | Avoca Beach, New South Wales | Australia | |

| Antipolis | S33°59.06’ E018°21.37’ | Oudekraal, Cape Town | South Africa |

| Aster | S34°03.891’ E018°20.955’ | Hout Bay, Cape Town | South Africa |

| RMS Athens | S33°53.85’ E018°24.57’ | Mouille Point, Cape Town | South Africa |

| HNLMS Bato | S34°10.998’ E018°25.560’ | Simon's Town | South Africa |

| Bia | S34°16'12.7" E018°22'38.3" | Olifantsbospunt, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| USCGC Bibb[11] | Florida | United States | |

| SAS Bloemfontein | S34°14.655’ E018°39.952’ | False Bay, Western Cape | South Africa |

| Barge Boss 400 | S34°02.216’ E018°18.573’ | Leeuwgat Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| HMAS Brisbane | Mooloolaba, Queensland | Australia | |

| East Indiaman Brunswick | S34°10.880’ E018°25.607’ | Simon's Town, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| HMAS Canberra | Barwon Heads, Victoria | Australia | |

| HMNZS Canterbury | Bay of Islands | New Zealand | |

| HMCS Cape Breton[12] | British Columbia | Canada | |

| Cape Matapan | S34°53.233' E018°24.533' | Table Bay, Cape Town | South Africa |

| Captain Keith Tibbetts | Cayman Brac | Cayman Islands | |

| CS Charles L Brown[13] | Sint Eustatius | Leeward Islands | |

| HMCS Chaudière[12] | British Columbia | Canada | |

| Clan Monroe | S34°08.817' E18°18.949' | Kommetjie, Cape Town | South Africa |

| Clan Stuart | S34°10.303’ E018°25.842’ | Simon's Town, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| HMCS Columbia[12] | British Columbia | Canada | |

| USCGC Cuyahoga | Virginia Capes | United States | |

| Australian Army ship Crusader | Flinders Reef off Cape Moreton, Queensland | Australia | |

| Daeyang Family | Robben Island, Cape Town | South Africa | |

| Dania[14] | Mombasa | Kenya | |

| SAS Fleur | S34°10.832’ E018°33.895’ | False Bay, Western Cape | South Africa |

| USCGC Duane[11] | Florida | United States | |

| Fontao | Durban | South Africa | |

| G.B. Church[12] | British Columbia | Canada | |

| SAS Gelderland | S34°02.070’ E018°18.180’ | Leeuwgat Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| Gemsbok | Cape Town | South Africa | |

| SATS General Botha | S34°13.679’ E018°38.290’ | False Bay | South Africa |

| USNS General Hoyt S. Vandenberg (T-AGM-10)[15] | Key West, Florida | United States | |

| Glen Strathallan | Plymouth | United Kingdom | |

| SAS Good Hope | S34°16.054’ E018°28.850’ | Smitswinkel Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| HMAS Hobart | Yankalilla Bay, South Australia | Australia | |

| VOIC ship Het Huis te Kraaiestein | S33°58.85’ E018°21.65’ | Oudekraal, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| Barque Highfields | S33°53’07.9” E18°25’49.8” | Table Bay, Cape Town | South Africa |

| Hypatia | S33°50.10’ E018°22.90’ | Robben Island, Cape Town | South Africa |

| Inganess Bay[16] | British Virgin Islands | ||

| Jura | Lake Constance | Switzerland | |

| Katsu Maru | S34°03.903’ E018°20.949’ | Hout Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| Keryavor and the Jo May | S34°02.037’ E018°18.636’ | Leeuwgat Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| USS Kittiwake | West Bay, Grand Cayman | Cayman Islands | |

| Lusitania | S34°23.40’ E018°29.65’ | Bellows Rock, Cape Point | South Africa |

| HMCS Mackenzie[12] | British Columbia | Canada | |

| Maori | S34°02.062’ E018°18.793’ | Leeuwgat Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| MS Zenobia | N 34°53.5’ E 33°39.1’ | Larnaca | Cyprus |

| HMCS Nipigon | Quebec | Canada | |

| Oakburn | S34°02.216’ E018°18.573’ | Leeuwgat Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| USS Oriskany[17] | Florida | United States | |

| MFV Orotava | S34°15.998’ E018°28.774’ | Smitswinkel Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| Oro Verde[18] | Cayman Islands | ||

| P29 Patrol Boat | Ċirkewwa | Malta | |

| P87 | Simon's Town | South Africa | |

| HMAS Perth[19] | Albany, Western Australia | Australia | |

| SAS Pietermaritzburg | S34°13.300’ E018° 28.452’ | Miller's Point, Western Cape near Simon’s Town | South Africa |

| MFV Princess Elizabeth | S34°16.068’ E018°28.839’ | Smitswinkel Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| Quarry Barge | S34°09.395’ E018°26.474’ | Glencairn, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| USS Rankin | Stuart, Florida | United States | |

| Rockeater | S34°16.127’ E018°28.890’ | Smitswinkel Bay, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| Romelia | S34°00.700’ E018°19.860’ | Llandudno, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| Rozi | Ċirkewwa | Malta | |

| SA Seafarer | S33°53.80’ E018°23.80’ | Mouille Point, Cape Town | South Africa |

| HMCS Saskatchewan[12] | British Columbia | Canada | |

| USS Scrimmage (MS Mahi) | Waianae, Hawaii | United States | |

| HMS Scylla | Whitsand Bay, Cornwall | United Kingdom | |

| USS Spiegel Grove[20] | Florida | United States | |

| Stanegarth | Stoney Cove | United Kingdom | |

| Star of Africa | Albatross Rock, Cape Peninsula | South Africa | |

| SS Thistlegorm | Ras Muhammad, Red Sea | Egypt | |

| HMAS Swan[21] | Dunsborough, Western Australia | Australia | |

| T-Barge | Durban | South Africa | |

| HMNZS Tui | Tutukaka Heads | New Zealand | |

| Um El Faroud | Qrendi | Malta | |

| Thomas T. Tucker | Olifantsbospunt, Cape peninsula | South Africa | |

| SAS Transvaal | S33°16.005’ E018°28.761’ | Smitswinkel Bay | South Africa |

| MV Treasure | S 33°40.30’ E 18°19.90’ | Koeberg | South Africa |

| Umhlali | S34°16.435' E18°22.487' | Olifantsbospunt, Cape Peninsula | South Africa |

| HMNZS Waikato | Tutukaka | New Zealand | |

| HMNZS Wellington | Wellington | New Zealand | |

| "Wreck Alley" – The Marie L, The Pat and The Beata[22] | British Virgin Islands | ||

| Wreck Alley | San Diego, California | United States | |

| Xihwu Boeing 737[12] | British Columbia | Canada | |

| HMCS Yukon[12] | San Diego, California | United States | |

| USAT Liberty[23] | Tulamben, Bali | Indonesia |

Reef dive sites

Coral reef areas

| Region/reef system name | Location | Country/Territory |

|---|---|---|

| Belize Barrier Reef | Caribbean | Belize |

| Chuuk | South western Pacific Ocean | Federated States of Micronesia |

| Great Barrier Reef | Queensland | Australia |

| Hurghada | Red Sea, Indian Ocean | Egypt |

| John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park | Florida | United States |

| Marsa Alam | Red Sea, Indian Ocean | Egypt |

| Diving in the Maldives | Indian Ocean | Maldives |

| Ras Muhammad National Park | Red Sea | Egypt |

| Diving in Thailand | Indian Ocean, South east Asia | Thailand |

| Sodwana Bay | Indian Ocean | South Africa |

| Diving in the Andaman Islands | Indian Ocean | India |

Rocky reefs

- Inland Sea, Gozo Malta

- Poor Knights Islands, North Island, New Zealand.

- Table Mountain National Park Marine Protected Area, Atlantic Ocean, near Cape Town, Western Cape province, South Africa

- Tsitsikamma National Park Marine Protected Area, Indian Ocean, Eastern Cape province, South Africa

Cave dive sites

Cave diving is underwater diving in water-filled caves. It may be considered an extreme sport. The equipment used varies depending on the circumstances, and ranges from breath hold to surface supplied, but almost all cave diving is done using scuba equipment, often in specialised configurations. Recreational cave diving is generally considered to be a type of technical diving due to the lack of a free surface during large parts of the dive, and often involves decompression.

- Boesmansgat, Mpumalanga, South Africa

- Sistema Dos Ojos, Yucatán, Mexico

- Sistema Nohoch Nah Chich, Yucatán, Mexico

- Sistema Ox Bel Ha Yucatán, Mexico

- Sistema Sac Actun, Yucatán, Mexico

- Zacatón, Mexico

Other sites

Quarry dive sites

Scuba diving quarries are depleted or abandoned rock quarries that have been allowed to fill with ground water, and rededicated to the purpose of scuba diving.[24] They may offer deep, clean, clear, still, fresh water with excellent visibility, or low visibility in turbid water from surface runoff. They have no currents or undertow. They are often used as training sites for new divers, where classes and certification dives are carried out.[24] Quarries used for scuba diving may be stocked with fish, and often feature contrived “wreck” sites, such as sunken boats, cars, and aircraft for divers to explore while diving. Many have a dive shop on site to rent out equipment and sell air fills and diving equipment. Lodging or camping areas may be available on site.[25]

Quarries in stone may have clear water, with greater visibility than in many inland lakes. Ground water is the primary source of the water that fills these quarries once they are no longer pumped out for mining operations. Many quarry mining operations are located in areas where filling from other, less clean sources, such as rivers and surface runoff of rainwater is not as likely.

Over time, most quarries tend to be contaminated with erosion products and nutrients from surface runoff, causing many to develop a green tint due to algae growth, and accumulations of silt on the bottoms and other surfaces.

Fresh water scuba diving does not require much difference in equipment from diving in the sea. Water temperatures generally decrease as depth increases, and may be as low as 4 °C (39 °F) at depth. In those temperatures dry suit diving is recommended, but in warmer temperatures, wetsuits may be sufficient. Diving in clean fresh water generally requires less post dive maintenance.[26]

The operators of scuba diving quarries may add objects or debris fields to the bottom of the quarry for divers to explore while scuba diving. Mostly these are man made objects such as boats, cars, and trucks. Some quarries have such large objects as school buses, small buildings, or commercial airliners on the bottom. These sites may be mapped out and marked with guide lines under the water, particularly if visibility is poor.[27][28][29][30]

The owners or operators of quarries may stock the quarry with fish to provide entertainment for divers. These are commonly the same species of fish that thrive naturally in local lakes and rivers, but some quarries are stocked with more exotic fish. The ecology is usually very limited.

Examples

- Dutch Springs, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

- Wazee Lake, Black River Falls, Wisconsin

- Quarry Park, St. Cloud, Minnesota

- Portsmouth Mine Pit Lake and Cuyuna Country State Recreation Area, near Crosby, Minnesota

- Stoney Cove, between Stoney Stanton and Sapcote in Leicestershire

- Dosthill quarry, near Tamworth, Staffordshire

- National Diving and Activity Centre, at Tidenham, Gloucestershire

Impact of recreational divers on the environment

The environmental impact of recreational diving is the effects of diving tourism on the marine environment. Usually these are considered to be adverse effects, and include damage to reef organisms by incompetent and ignorant divers, but there may also be positive effects when the environment is recognised by the local communities to be worth more in good condition than degraded by inappropriate use, which encourages conservation efforts.

During the 20th century recreational scuba diving was considered to have generally low environmental impact, and was consequently one of the activities permitted in most marine protected areas. Since the 1970s diving has changed from an elite activity to a more accessible recreation, marketed to a very wide demographic. To some extent better equipment has been substituted for more rigorous training, and the reduction in perceived risk has shortened minimum training requirements by several training agencies. Training has concentrated on an acceptable risk to the diver, and paid less attention to the environment. The increase in the popularity of diving and in tourist access to sensitive ecological systems has led to the recognition that the activity can have significant environmental consequences.[31]

Scuba diving has grown in popularity during the 21st century, as is shown by the number of certifications issued worldwide, which has increased to about 23 million by 2016 at about one million per year.[32] Scuba diving tourism is a growth industry, and it is necessary to consider environmental sustainability, as the expanding impact of divers can adversely affect the marine environment in several ways, and the impact also depends on the specific environment. Tropical coral reefs are more easily damaged by poor diving skills than some temperate reefs, where the environment is more robust due to rougher sea conditions and fewer fragile, slow-growing organisms. The same pleasant sea conditions that allow development of relatively delicate and highly diverse ecologies also attract the greatest number of tourists, including divers who dive infrequently, exclusively on vacation and never fully develop the skills to dive in an environmentally friendly way.[33] Low impact diving training has been shown to be effective in reducing diver contact.[31]

Environmental impact can expand in scope when a destination is commercially developed to provide more facilities to encourage the expansion of tourism.

Scuba diving tourism

Scuba diving tourism is the industry based on servicing the requirements of recreational divers at destinations other than where they live. It includes aspects of training, equipment sales, rental and service, guided experiences and environmental tourism.[33][34]

Customer satisfaction is largely dependent on the quality of services provided, and personal communication has a strong influence on the popularity of specific service providers in a region.[33]

Scuba diving tourism services are usually focused on providing visiting recreational divers with access to local dive sites, or organising group tours to regions where desirable dive sites exist.

References

- Diving Advisory Board (10 November 2017). NO. 1235 Occupational Health and Safety Act, 1993: Diving regulations: Inclusion of code of practice inshore diving 41237. Code of Practice Inshore Diving (PDF). Department of Labour, Republic of South Africa. pp. 72–139.

- Diving Advisory Board. Code Of Practice for Scientific Diving (PDF). Pretoria: The South African Department of Labour. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "Drilling Lexicon". IADC. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Definitions". Ontario Regulation 629/94, Amended to O. Reg. 155/04 Diving Operations.

- "Dive Site and Dive Base". A Guide to the Occupational Diving Regulations for the Seafood Harvesting Industry (PDF). Nova Scotia Environment and Labour Occupational Health and Safety Division. p. 4.

- Your African Safari (4 June 2015). "Five top dive sites in South Africa". Africa Geographic.

- Pfaff, Maya C.; Logston, Renae C.; Raemaekers, Serge J. P. N.; Hermes, Juliet C.; Blamey, Laura K.; Cawthra, Hayley C.; Colenbrander, Darryl R.; Crawford, Robert J. M.; Day, Elizabeth; du Plessis, Nicole; Elwen, Simon H.; Fawcett, Sarah E.; Jury, Mark R.; Karenyi, Natasha; Kerwath, Sven E.; Kock, Alison A.; Krug, Marjolaine; Lamberth, Stephen J.; Omardien, Aaniyah; Pitcher, Grant C.; Rautenbach, Christo; Robinson, Tamara B.; Rouault, Mathieu; Ryan, Peter G.; Shillington, Frank A.; Sowman, Merle; Sparks, Conrad C.; Turpie, Jane K.; van Niekerk, Lara; Waldron, Howard N.; Yeld, Eleanor M.; Kirkman, Stephen P. (2019). "A synthesis of three decades of socio-ecological change in False Bay, South Africa: setting the scene for multidisciplinary research and management". Elementa Science of the Anthropocene. 7 (32). doi:10.1525/elementa.367. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0)

- "Government Notice 695: Marine Living Resources Act (18/1998): Notice declaring the Table Mountain National Park Marine Protected Area under section 43" (PDF). Government Gazette: 3–9. 4 June 2004.

- Sink, K.; Harris, J.; Lombard, A. (October 2004). Appendix 1. South African marine bioregions (PDF). South African National Spatial Biodiversity Assessment 2004: Technical Report Vol. 4 Marine Component DRAFT (Report). pp. 97–109.

- "R118. Draft Regulations for the management of the Isimangaliso Marine Protected Area" (PDF). Regulation Gazette No. 10553. Pretoria: Government Printer. 608 (39646). 3 February 2016.

- Williams, Chris; Bowen, Linda (2008). "Wrecks of the Duane and Bibb" (PDF). Advanced Diver Magazine Ezine (1, reprinted from ADM issue 4): 62–72. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- "ARSBC". Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- "Charlie Brown Artificial Reef". Golden Rock Dive Center. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "5 Star PADI IDC Centre, Kenya, Zanzibar". Buccaneer Diving. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- "Vandenberg sinking this morning". MSNBC. Associated Press. 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- "BVI Dive Site: Wreck of the Inganess Bay". Bvidiving.com. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- Barnette, Michael C. (2008). Florida's Shipwrecks. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5413-6.

- "The Cayman Islands Shipwreck Expo Directory Capt. Dan Berg's Guide to Shipwrecks information". Aquaexplorers.com. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- "HMAS Perth (II) - Royal Australian Navy". Navy.gov.au. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- "The Spiegel Grove is believed to be the largest ever wreck deliberately sunk as a diving site". Fla-keys.com. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- "HMAS Swan (III) - Royal Australian Navy". Navy.gov.au. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- "Cooper Island". Dive BVI. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- "DailyDive.com - Scuba Diving Community". DailyDive. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- http://www.padi.com/scuba/default.aspx

- http://www.divessi.com/

- http://www.huronscuba.com/diveInfo/documents/definitions/basicScubaDivingEquipment.html

- http://www.divegilboa.com/

- http://www.portagequarry.com/

- http://www.whitestarquarry.com

- https://diveinaustralia.com.au/hmas-brisbane-shipwreck-mooloolaba-sunshine-coast

- Hammerton, Zan (2014). SCUBA-diver impacts and management strategies for subtropical marine protected areas (Thesis). Southern Cross University.

- Lucrezi, Serena (18 January 2016). "How scuba diving is warding off threats to its future". The Conversation. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Dimmock, Kay; Cummins, Terry; Musa, Ghazali (2013). "Chapter 10: The business of Scuba diving". In Musa, Ghazali; Dimmock, Kay (eds.). Scuba Diving Tourism. Routledge. pp. 161–173.

- Dimmock, Kay; Musa, Ghazali, eds. (2015). Scuba diving tourism system: a framework for collaborative management and sustainability. Southern Cross University School of Business and Tourism.

External links

TOP10 diving sites in Red Sea, Egypt https://www.zesea.com/en/red-sea-10-best-diving-sites-egypt/

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Scuba diving. |

![]() Media related to Underwater diving sites at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Underwater diving sites at Wikimedia Commons