Deepsea Challenger

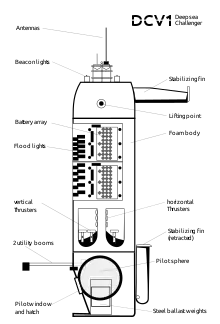

Deepsea Challenger (DCV 1) is a 7.3-metre (24 ft) deep-diving submersible designed to reach the bottom of Challenger Deep, the deepest-known point on Earth. On 26 March 2012, Canadian film director James Cameron piloted the craft to accomplish this goal in the second manned dive reaching the Challenger Deep.[1][2][3][4] Built in Sydney, Australia by the research and design company Acheron Project Pty Ltd, Deepsea Challenger includes scientific sampling equipment and high-definition 3-D cameras; it reached the ocean's deepest point after two hours and 36 minutes of descent from the surface.[1][5]

Drawing of the DCV1, based on imagery from the Deepsea Challenger website (not to scale) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Deepsea Challenger |

| Builder: | Acheron Project Pty Ltd |

| Launched: | 26 January 2012 |

| In service: | 2012 |

| Status: | Active as of 2018 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Deep-submergence vehicle |

| Displacement: | 11.8 tons |

| Length: | 7.3 m (24 ft) |

| Installed power: | electric motor |

| Propulsion: | 12 thrusters |

| Speed: | 3 knots (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph) |

| Endurance: | 56 hours |

| Test depth: | 11,000 m (36,000 ft) |

| Complement: | 1 |

Development

Deepsea Challenger was built in Australia, in partnership with the National Geographic Society and with support from Rolex, in the Deepsea Challenge program. The construction of the submersible was headed by Australian engineer Ron Allum.[6] Many of the submersible developer team members hail from Sydney's cave-diving fraternity including Allum himself with many years' cave-diving experience.

Working in a small engineering workshop in Leichhardt, Sydney, Allum created new materials including a specialized structural syntactic foam called Isofloat,[7] capable of withstanding the huge compressive forces at the 11-kilometre (6.8 mi) depth. The new foam is unique in that it is more homogeneous and possesses greater uniform strength than other commercially available syntactic foam yet, with a specific density of about 0.7, will float in water. The foam is composed of very small hollow glass spheres suspended in an epoxy resin and comprises about 70% of the submarine's volume.[8]

The foam's strength enabled the Deepsea Challenger designers to incorporate thruster motors as part of the infrastructure mounted within the foam but without the aid of a steel skeleton to mount various mechanisms. The foam supersedes gasoline-filled tanks for flotation as used in the historic bathyscaphe Trieste.

Allum also built many innovations, necessary to overcome the limitations of existing products (and presently undergoing development for other deep sea vehicles). These include pressure-balanced oil-filled thrusters;[9] LED lighting arrays; new types of cameras; and fast, reliable penetration communication cables allowing transmissions through the hull of the submersible.[10] Allum gained much of his experience developing the electronic communication used in Cameron's Titanic dives in filming Ghosts of the Abyss, Bismarck and others.[10][11]

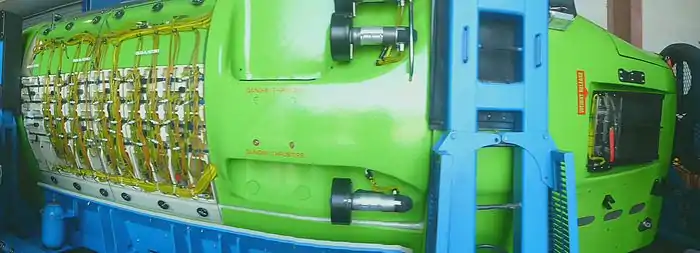

Power systems for the submarine were supplied by lithium batteries that were housed within the foam and can be clearly seen in publicity photographs of the vessel.[12] The lithium battery charging systems were designed by Ron Allum.[13] The submersible contains over 180 onboard systems, including batteries, thrusters, life support, 3D cameras, and LED lighting.[14] These interconnected systems are monitored and controlled by a programmable automation controller (PAC) from Temecula, California-based controls manufacturer Opto 22.[15][16][17][18] During dives, the control system also recorded depth, heading, temperature, pressure, battery status, and other data, and sent it to the support ship at three-minute intervals[19] via an underwater acoustic communication system developed by West Australian company L-3 Nautronix.[20][21]

The crucial structural elements, such as the backbone and pilot sphere that carried Cameron, were engineered by the Tasmanian company Finite Elements.[22] The design of the interior of the sphere, including fireproofing, condensation management and mounting of control assemblies, was undertaken by Sydney-based industrial design consultancy Design + Industry.[23]

Specifications

The submersible features a pilot sphere measuring 1.1 metres (43 in) in diameter, large enough for only one occupant.[24] The sphere, with steel walls 64 mm (2.5 in) thick, was tested for its ability to withstand the required 114 megapascals (16,500 pounds per square inch) of pressure in a pressure chamber at Pennsylvania State University.[25] The sphere sits at the base of the 11.8-tonne (13.0-short-ton) vehicle. The vehicle operates in a vertical attitude, and carries 500 kg (1,100 lb) of ballast weight that allows it to both sink to the bottom, and when released, rise to the surface. If the ballast weight release system fails, stranding the craft on the seafloor, a backup galvanic release is designed to corrode in salt water in a set period of time, allowing the sub to automatically surface.[26] Deepsea Challenger is less than one-tenth the weight of its predecessor of fifty years, the bathyscaphe Trieste; the modern vehicle also carries dramatically more scientific equipment than Trieste, and is capable of more rapid ascent and descent.[27]

Beacons and antennae, top

Beacons and antennae, top Battery array.

Battery array. One of the thrusters.

One of the thrusters. One of two main ballast weights.

One of two main ballast weights. The pilot sphere before installation.

The pilot sphere before installation. Hatch and viewport.

Hatch and viewport. Pilot sphere, interior.

Pilot sphere, interior.

Dives

Early dives

In late January 2012, to test systems, Cameron spent three hours in the submersible while submerged just below the surface in Australia's Sydney Naval Yard.[28] On 21 February 2012, a test dive intended to reach a depth of over 1,000 m (3,300 ft) was aborted after only an hour because of problems with cameras and life support systems.[29] On 23 February 2012, just off New Britain Island, Cameron successfully took the submersible to the ocean floor at 991 m (3,251 ft), where it made a rendezvous with a yellow remote operated vehicle operated from a ship above.[30] On 28 February 2012, during a seven-hour dive, Cameron spent six hours in the submersible at a depth of 3,700 m (12,100 ft). Power system fluctuations and unforeseen currents presented unexpected challenges.[31][32]

On 4 March 2012, a record-setting dive to more than 7,260 m (23,820 ft) stopped short of the bottom of the New Britain Trench when problems with the vertical thrusters led Cameron to return to the surface.[33] Days later, with the technical problem solved, Cameron successfully took the submersible to the bottom of the New Britain Trench, reaching a maximum depth of 8,221 m (26,972 ft).[33] There, he found a wide plain of loose sediment, anemones, jellyfish and varying habitats where the plain met the walls of the canyon.[33]

Challenger Deep

On 18 March 2012, after leaving the testing area in the relatively calm Solomon Sea, the submersible was aboard the surface vessel Mermaid Sapphire, docked in Apra Harbor, Guam, undergoing repairs and upgrades, and waiting for a calm enough ocean to carry out the dive.[34][35] By 24 March 2012, having left port in Guam days earlier, the submersible was aboard one of two surface vessels that had departed the Ulithi atoll for the Challenger Deep.[36][37]

On 26 March 2012 it was reported that it had reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

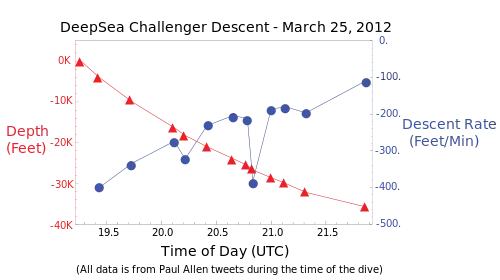

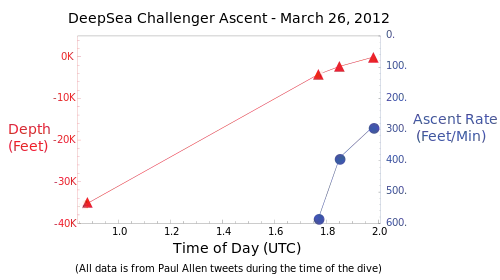

Descent, from the beginning of the dive to arrival at the seafloor, took two hours and 37 minutes, almost twice as fast as the descent of Trieste.[39] A Rolex watch, "worn" on the sub's robotic arm, continued to function normally throughout the dive.[40][41] Not all systems functioned as planned on the dive: bait-carrying landers were not dropped in advance of the dive because the sonar needed to find them on the ocean floor was not working, and hydraulic system problems hampered the use of sampling equipment.[39] Nevertheless, after roughly three hours on the seafloor and a successful ascent, further exploration of the Challenger Deep with the unique sub was planned for later in the Spring of 2012.[39]

Records

On 26 March 2012, Cameron reached the bottom of the Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the Mariana Trench. The maximum depth recorded during this record-setting dive was 10,908 metres (35,787 ft).[42] Measured by Cameron, at the moment of touchdown, the depth was 10,898 m (35,756 ft).[43] It was the fourth-ever dive to the Challenger Deep and the second manned dive (with a maximum recorded depth slightly less than that of Trieste's 1960 dive). It was the first solo dive and the first to spend a significant amount of time (three hours) exploring the bottom.[1]

Subsequent events

Deepsea Challenger was donated to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution for the studies of its technological solutions in order to incorporate some of those solutions into other vehicles to advance deep-sea research.[44] On 23 July 2015, it was transported from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to Baltimore to be shipped to Australia for a temporary loan. While on a flatbed truck on Interstate 95 in Connecticut, the truck caught fire, resulting in damage to the submersible. The likely cause of the fire was from the truck's brake failure which ignited its rear tires. Connecticut fire officials speculated that it was a total loss to the Deepsea Challenger; however, the actual extent of the damage was not reported. The submersible was transported back to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution after the fire.[45] As of February 2016, it had been moved to California for repairs.[46]

Similar efforts

As of February 2012, several other vehicles are under development to reach the same depths. The groups developing them include:

- Triton Submarines, a Florida-based company that designs and manufactures private submarines, whose vehicle, Triton 36000/3, will carry a crew of three to the seabed in 120 minutes.[47]

- Virgin Oceanic, sponsored by Richard Branson's Virgin Group, is developing a submersible designed by Graham Hawkes, DeepFlight Challenger,[48] with which the solo pilot will take 140 minutes to reach the seabed.[49]

- DOER Marine,[50] a San Francisco Bay Area based marine technology company established in 1992, that is developing a vehicle, Deepsearch (and Ocean Explorer HOV Unlimited),[51] with some support from Google's Eric Schmidt with which a crew of two or three will take 90 minutes to reach the seabed, as the program Deep Search.[51]

See also

- Challenger expedition – Oceanographic research expedition (1872–1876)

- Deep-sea exploration – Investigation of physical, chemical, and biological conditions on the sea bed

- Timeline of diving technology – A chronological list of notable events in the history of underwater diving

References

- Than, Ker (25 March 2012). "James Cameron Completes Record-Breaking Mariana Trench Dive". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Broad, William J. (25 March 2012). "Filmmaker in Submarine Voyages to Bottom of Sea". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- "James Cameron has reached deepest spot on Earth". NBC News. AP. 25 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Ingraham, Nathan (9 March 2012). "James Cameron and his Deepsea Challenger submarine". theverge.com. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "Race to the bottom of the ocean: Cameron". BBC. 22 February 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Allum, Ron. "Ron Allum". Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Allum, Ron. "Isofloat". Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Bausch, Jeffrey (March 12, 2012). "Hollywood director James Cameron to pilot submarine to the bottom of Mariana Trench". Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- "Thruster with integral PBOF driver". Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- "Ron Allum". Deepsea Challenge: National Geographic. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Ron Allum Filmography". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Lithium polymer (LIPO) cell packs". Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Systems Technology". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Ray, Tiffany (11 May 2012). "Temecula Firm Gets Role in James Cameron Project". The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Maio, Pat (9 April 2012). "Filmmaker James Cameron pilots to bottom of Mariana Trench, thanks to Temecula's Opto 22". North County Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Performance Under Pressure – Off-the-shelf SNAP PAC System controls DEEPSEA CHALLENGER for James Cameron's historic dive". Opto 22. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "James Cameron's Historic Return to Mariana Trench Relies on Latest Advances in Engineering and Technology" (PDF) (Press release). Opto 22. 3 April 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "We've Got a Deep-Diving Sub". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Burke, Louise (16 April 2012). "WA engineers hear voice from the deep". The West Australian. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- Roberts, Paul. "Voices from the deep – Acoustic communication with a submarine at the bottom of the Mariana Trench" (PDF). Australian Acoustical Society. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- David Beniuk (27 March 2012). "Tassie engineer elated by Cameron's dive". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- "Deepsea Challenger Pilot Sphere". Design and Industry. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- "Sub Facts". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "Pilot Sphere". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "Systems & Technology". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "Then and now". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "Jim Takes First Piloted Dive". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 31 January 2012. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "Camera Hell". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 22 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "We've Got a Deep-Diving Sub". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "Postdive Truths Revealed". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- "A Critical Step". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Cameron, James (8 March 2012). "You'd have loved it". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- "Ocean Swells". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 10 March 2012. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- "A Hive of Work". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 18 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- "Mariana Trench Mission This Weekend?". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). 24 March 2012. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- "Cameron heads to ocean floor". Ottawa Citizen. March 21, 2012. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- Allen, Paul G (27 March 2012). "Paul Allen Tweets from Challenger Deep". twitter.com. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- William J. Broad (27 March 2012). "Director James Cameron tours earth's deepest point". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Rolex Deep-sea History". deepseachallenge.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- "About the Rolex Deepsea Challenge". rolex.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- "DEEPSEA CHALLENGE Facts at a Glance". Deepsea Challenge (National Geographic). Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Deepsea Challenge 3D (2014)

- "James Cameron Partners With WHOI". National Geographic. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- "Historic Submarine Used by James Cameron Likely Destroyed in Fire: Officials". NBC Connecticut. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Driscoll, Sean F. (16 February 2016). "Deepsea Challenger moves to California for repairs". Cape Cod Times. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- "Triton 36,000 Full Ocean Depth Submersible". Triton Submarines. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Virgin Oceanic, Operations Team (accessed 25 March 2012)

- "Virgin Oceanic". Virgin Oceanic. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- "About DOER Marine". DOER Marine. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- "Deep Search". DOER Marine. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

External links

Media related to Deepsea Challenger at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Deepsea Challenger at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Article on usage of Computational Fluid Dynamics during the design process of the Deepsea Challenger

- NGS video: Cameron's return from Challenger Deep

- Deepsea Challenge 3D at IMDb, a 2014 National Geographic Channel documentary.