Social Democrats, USA

Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA) is a small political association of democratic socialists and social democrats founded in 1972. The Socialist Party of America (SPA) had stopped running independent presidential candidates and consequently the term party in the SPA's name had confused the public. Replacing the socialist label with "social democrats," was meant to disassociate the ideology of SDUSA with that of the Soviet Union.[3]

Social Democrats, USA | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | December 30, 1972 |

| Preceded by | Socialist Party of America |

| Newspaper | New America (until 1985) |

| Youth wing | Young Social Democrats |

| Ideology | Social democracy[1] Democratic socialism[2] |

| Political position | Center-left |

| International affiliation | Socialist International (1973–2005) |

| Colors | Red |

| Website | |

| socialistcurrents.org | |

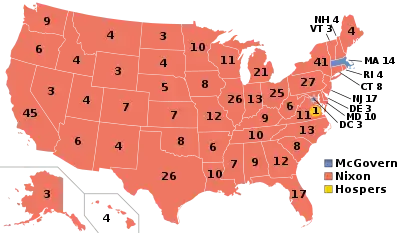

SDUSA pursued an electoral strategy of political realignment intended to organize labor unions, civil rights organizations and other constituencies into a coalition that would transform the Democratic Party into a social democratic party. The realignment strategy emphasized working with unions and especially the AFL–CIO, putting an emphasis on economic issues that would unite working class voters. SDUSA opposed the so-called New Politics of Senator George McGovern, pointing to the rout suffered in the 1972 presidential election.

SDUSA's organizational activities included sponsoring discussions and issuing position papers—however, it was known mainly because of its members' activities in other organizations. It included civil rights activists and leaders of labor unions such as Bayard Rustin, Norman Hill and Tom Kahn of the AFL–CIO as well as Sandra Feldman and Rachelle Horowitz of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). Internationally, the group supported the dissident Polish labor organization Solidarity and several anti-communist political movements in global hot spots.

SDUSA's politics were criticized by former SPA Chairman Michael Harrington, who in 1972 announced that he favored an immediate pull-out of American forces from Vietnam. After losing all votes at the 1972 convention that changed the SPA to SDUSA, Harrington resigned in 1973 to form the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC), forerunner of Democratic Socialists of America.

Socialist Party of America

By the early 1970s, the Socialist Party of America (SPA) was publicly associated with A. Philip Randolph, the civil rights and labor union leader; and with Michael Harrington, the author of The Other America. Even before the 1972 convention, Harrington had resigned as an Honorary Chairperson of the SPA[3] "because he was upset about the group’s failure to enthusiastically support George McGovern and because of its views on the Vietnam War".[4]

In its 1972 Convention, the SPA had two Co-Chairmen, Bayard Rustin and Charles S. Zimmerman of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU);[5] and a First National Vice Chairman, James S. Glaser, who were re-elected by acclamation.[3] In his opening speech to the Convention, Co-Chairman Bayard Rustin called for SDUSA to organize against the "reactionary policies of the Nixon Administration" and Rustin also criticized the "irresponsibility and élitism of the 'New Politics' liberals".[3]

The party changed its name to Social Democrats, USA, by a vote of 73 to 34.[3] Changing the name of the Socialist Party of America to Social Democrats, USA, was intended to be "realistic" as the intention was to respond to the end of the running of actual SPA candidates for office and to respond to the confusions of Americans. The New York Times observed that the Socialist Party had last sponsored Darlington Hoopes as candidate for President in 1956 and who received only 2,121 votes, which were cast in only six states. Because the SPA no longer sponsored party candidates in elections, continued use of the name "party" was "misleading" and hindered the recruiting of activists who participated in the Democratic Party according to the majority report. The name "Socialist" was replaced by "Social Democrats" because many American associated the term "socialism" with Marxism–Leninism.[3] Moreover, the organization sought to distinguish itself from two small Marxist parties, the Socialist Workers Party and the Socialist Labor Party.[6]

During the 1972 Convention, the majority (Unity Caucus) won every vote by a ratio of two to one. The Convention elected a national committee of 33 members, with 22 seats for the majority caucus, eight seats for the Coalition Caucus of Harrington, two for the left-wing Debs Caucus and one for the independent Samuel H. Friedman.[7] Friedman and the minority caucuses had opposed the name change.[3]

The convention voted on and adopted proposals for its program by a two-one vote. On foreign policy, the program called for "firmness toward Communist aggression". However, on the Vietnam War the program opposed "any efforts to bomb Hanoi into submission" and instead it endorsed negotiating a peace agreement, which should protect communist political cadres in South Vietnam from further military or police reprisals. Harrington's proposal for a ceasefire and immediate withdrawal of American forces was defeated.[7] Harrington complained that after its convention the SPA had endorsed George McGovern only with a statement loaded with "constructive criticism" and that it had not mobilized enough support for McGovern. The majority caucus's Arch Puddington replied that the California branch was especially active in supporting McGovern while the New York branch were focusing on a congressional race.[6]

When the SPA changed its name to SDUSA, Bayard Rustin became its public spokesman. According to Rustin, SDUSA aimed to transform the Democratic Party into a social democratic party. A strategy of re-alignment was particularly associated with Max Shachtman.[8]

Some months after the convention, Harrington resigned his membership in SDUSA and he and some of his supporters from the Coalition Caucus soon formed the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC).[9] Many members of the Debs Caucus resigned from SDUSA and some of them formed the Socialist Party USA.[10] The changing of the name of the SPA to SDUSA and the 1973 formation of DSOC and the SPUSA represented a split in the American socialist movement.

Early years

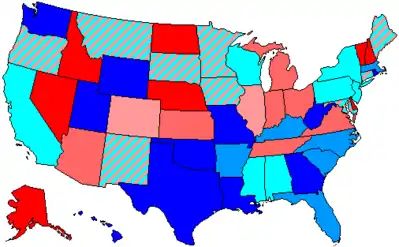

| In the 1972 Congressional election, the majority of Americans voted for Democratic Congressmen and this map shows the House seats by party holding plurality in state | |

80.1–100% Republican |

80.1–100% Democratic |

60.1–80% Republican |

60.1–80% Democratic |

up to 60% Republican |

up to 60% Democratic |

In domestic politics, the SDUSA leadership emphasized the role of the American labor movement in advancing civil rights and economic justice. The domestic program followed the recommendations of Rustin's article "From Protest to Politics" in which Rustin analyzed the changing economy and its implications for African Americans. Rustin wrote that the rise of automation would reduce the demand for low-skill high-paying jobs, which would jeopardize the position of the urban black working class, particularly in the Northern United States. The needs of the black community demanded a shift in political strategy, where blacks would need to strengthen their political alliance with mostly white unions and other organizations (churches, synagogues and the like) to pursue a common economic agenda. It was time to move from protest to politics, wrote Rustin.[11] A particular danger facing the black community was the chimera of identity politics, particularly the rise of Black Power which Rustin dismissed as a fantasy of middle-class African-Americans that repeated the political and moral errors of previous black nationalists while alienating the white allies needed by the black community.[12]

SDUSA documents had similar criticisms of the agendas advanced by middle class activists increasing their role in the Democratic Party. SDUSA members stated concerns about an exaggerated role of middle-class peace activists in the Democratic Party, particularly associated with the "New Politics" of Senator George McGovern, whose presidential candidacy was viewed as an ongoing disaster for the Democratic Party and for the United States.[3][13] In electoral politics, SDUSA aimed to transform the Democratic Party into a social democratic party.[14]

In foreign policy, most of the founding SDUSA leadership called for an immediate cessation of the bombing of North Vietnam. They demanded a negotiated peace treaty to end the Vietnam War, but the majority opposed a unilateral withdrawal of American forces from Vietnam, suggesting that such a withdrawal would lead to an annihilation of the free labor unions and of the political opposition.[3][15][16] After the withdrawal of American forces from Vietnam and the victory of the Communist Party of Vietnam and the Viet Cong, SDUSA supported humanitarian assistance to refugees and condemned Senator McGovern for his failure to support such assistance.[17][18]

Organizational activities

SDUSA was governed by biannual conventions which invited the participation of interested observers. These gatherings featured discussions and debates over proposed resolutions, some of which were adopted as organizational statements. The group frequently made use of outside speakers at these events: non-SDUSA intellectuals ranged from neoconservatives like Jeane Kirkpatrick on the right to democratic socialists like Paul Berman on the left and similarly a range of academic, political and labor-union leaders were invited. These meetings also functioned as reunions for political activists and intellectuals, some of whom worked together for decades.[19] SDUSA also published a newsletter and occasional position papers, issued statements supporting labor unions and workers' interests at home and overseas, the existence of Israel and the Israeli labor movement.[20] From 1979–1989, SDUSA members were organized to support of Solidarity, the independent labor union of Poland.[21]

The organization also attempted to exert influence through endorsements of presidential candidates. The group's 1976 National Convention, held in New York City, formally endorsed the Democratic ticket of Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale and pledged the group to "work enthusiastically" for the election of the pair in November.[22] The organization took a less assertive approach during the divisive 1980 campaign, marked as it was by a heated primary challenge to President Carter by Senator Edward Kennedy and SDUSA chose not to hold its biannual convention until after the termination of the fall campaign. The election of conservative Ronald Reagan was chalked up to the failure of the Democrats to "appeal to their traditional working class constituency".[23]

Early in 1980, long-time National Director Carl Gershman resigned his position to be replaced by Rita Freedman.[24] Freedman previously had served as organizer and chair of SDUSA's key New York local.[24]

SDUSA dues were paid annually in advance, with members receiving a copy of the organization's official organ, the tabloid-sized newspaper New America. The dues rate was $25 per year in 1983.[25]

Member activities

Small organizations associated with the Debs–Thomas Socialist Party have served as schools for the leadership of social-movement organizations, including the civil rights movement and the sixties radicalism. These organizations are now chiefly remembered because of their members' leadership of large organizations that directly influenced the United States and international politics.[26][27] After 1960, the party also functioned "as an educational organization" and "a caucus of policy advocates on the left wing of the Democratic Party".[28] Similarly, SDUSA was known mainly because of the activities of its members, many of whom publicly identified themselves as members of SDUSA. Members of SDUSA have served as officers for governmental, private and not-for-profit organizations. A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and Norman Hill were leaders of the civil rights movement. Tom Kahn, Sandra Feldman and Rachelle Horowitz were officers of labor unions. Carl Gershman and Penn Kemble served in governmental and non-governmental organizations, particularly in foreign policy. Philosopher Sidney Hook was a public intellectual. Writing after the death of Tom Kahn, Ben Wattenberg commented that SDUSA as an "umbrella organization" associated with other letterhead organizations, saying the following:

[SDUSA members seemed to be] ingeniously trying to bury the Soviet Union in a blizzard of letterheads. It seemed that each of Tom's colleagues—Penn Kemble, Carl Gershman, Josh Muravchik and many more—ran a little organization, each with the same interlocking directorate listed on the stationery. Funny thing: The Letterhead Lieutenants did indeed churn up a blizzard, and the Soviet Union is no more.

I never did quite get all the organizational acronyms straight—YPSL, LID, SP, SDA, ISL—but the key words were "democratic", "labor", "young" and, until events redefined it away from their understanding, "socialist". Ultimately, the umbrella group became "Social Democrats, U.S.A", and Tom Kahn was a principal "theoretician".

They talked and wrote endlessly, mostly about communism and democracy, despising the former, adoring the latter. It is easy today to say "anti-communist" and "pro-democracy" in the same breath. But that is because American foreign policy eventually became just such a mixture, thanks in part to those "Yipsels" (Young People's Socialist League), with Tom Kahn as provocateur-at-large.

On the conservative side, foreign policy used to be anti-communist, but not very pro-democracy. And foreign policy liberal-style might be piously pro-democracy, but nervous about being anti-communist. Tom theorized that to be either, you had to be both.

It was tough for labor-liberal intellectuals to be "anti-communist" in the 1970s. It meant being taunted as "Cold Warriors" who saw "Commies under every bed" and being labeled as—the unkindest cut—"right-wingers".[29]

A. Philip Randolph

The long-time leader and intellectual architect of the civil rights movement, A. Philip Randolph was also a visible member of the Socialist Party of Norman Thomas. He remained with the organization when it changed its name to SDUSA. Along with ILGWU President David Dubinsky, Randolph was honored at the 1976 SDUSA convention.[30]

A. Philip Randolph came to national attention as the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Randolph proposed a march on Washington, D.C. to protest racial discrimination in the United States armed forces. Meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Oval Office, Randolph respectfully, politely, but firmly told President Roosevelt that blacks would march in the capital unless desegregation would occur. The planned march was canceled after President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 (the Fair Employment Act), which banned discrimination in defense industries and federal agencies.

In 1942, an estimated 18,000 blacks gathered at Madison Square Garden to hear Randolph kick off a campaign against discrimination in the military, in war industries, in government agencies and in labor unions. Following the act, during the Philadelphia Transit Strike of 1944 the government backed African American workers' striking to gain positions formerly limited to white employees.

In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished racial segregation in the armed forces through Executive Order 9981.[31] Randolph was the nominal leader of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was organized by Bayard Rustin and his younger associates. At this march, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. Soon afterwards, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed.

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin was National Chairman of SDUSA and also was President of the A. Philip Randolph Institute.[32][33]

Rustin had had a long association with A. Philip Randolph and with pacifist movements. In 1956, Rustin advised Martin Luther King Jr. who was organizing the Montgomery bus boycott. According to Rustin: "I think it's fair to say that Dr. King's view of non-violent tactics was almost non-existent when the boycott began. In other words, Dr. King was permitting himself and his children and his home to be protected by guns". Rustin convinced King to abandon the armed protection.[34][35] The following year, Rustin and King began organizing the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

Rustin and Randolph organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. On September 6, 1963, Rustin and Randolph appeared on the cover of Life magazine as "the leaders" of the March.[36]

From protest to politics

After passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, Rustin advocated closer ties between the civil rights movement and the Democratic Party and its base among the working class.

With the assistance of Tom Kahn,[37] Rustin wrote the 1965 article "From protest to politics",[38] which analyzed the changing economy and its implications for black Americans. This article stated that the rise of automation would reduce the demand for low-skill high-paying jobs, which would jeopardize the position of the urban black working class, particularly in the Northern United States. To pursue its economic agenda, the black community needed to shift political strategy, strengthening its political alliance with mostly white unions and other organizations (churches, synagogues and the like). As its agenda shifted from civil rights to economic justice, the black community's tactics needed to shift from protest to politics, wrote Rustin.[11] A particular danger facing the Negro community was the chimera of identity politics, particularly the rise of "Black Power", for which Rustin expressed contempt:

Wearing my hair Afro style, calling myself an Afro-American, and eating all the chitterlings I can find are not going to affect Congress.[39]

Rustin wrote that "Black Power" repeated the moral errors of previous black nationalists while alienating the white allies needed by the black community.[12]

Influence on William Julius Wilson

Rustin's analysis was supported by the later research by William Julius Wilson.[39] Wilson documented an increase in inequality within the black community, following educated blacks moving into white suburbs and following the decrease of demand for low-skill labor as industry declined in the Northern United States. Such economic problems were not being addressed by a civil rights leadership focused on "affirmative action", a policy benefiting the truly advantaged within the black community. Wilson's criticism of the neglect of working class and poor African Americans by civil rights organizations led to his being mistaken for a conservative, despite his having identified himself as a Rustin-style social democrat. Wilson has served on the advisory board of Social Democrats, USA.[40]

Labor movement, trade unions and social democracy

Rustin increasingly worked to strengthen the labor movement, which he saw as the champion of empowerment for the African American community and for economic justice for all Americans. He contributed to the labor movement's two sides, economic and political, through support of labor unions and social democratic politics.

He was the founder and became the Director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, which coordinated the AFL–CIO's work on civil rights and economic justice. He became a regular columnist for the AFL–CIO newspaper.

On the political side of the labor movement, Rustin increased his visibility as a leader of the American social democracy. He was a founding National Co-Chairman of Social Democrats, USA.[3][14]

Human rights and ending discrimination against gays

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Rustin worked as a human rights and election monitor for Freedom House. He also testified on behalf of New York State's Gay Rights Bill. In 1986, he gave the speech "The new 'niggers' are gays" in which he asserted:

Today, blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change. Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new "niggers" are gays. [...] It is in this sense that gay people are the new barometer for social change. [...] The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people.[41]

Rustin also helped to write a report on peaceful means to end apartheid (racial segregation) in South Africa.[42]

Norman Hill

Norman Hill is an influential African American administrator, activist and labor leader.[43]

Graduating in 1956, he was one of the first African Americans to graduate from Haverford College. Joining the civil rights movement and working in Chicago, Hill was an organizer for the Youth March for Integrated Schools and then Secretary of Chicago Area Negro American Labor Council and Staff Chairman of the Chicago March Conventions. In the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Hill was first the East Coast Field Secretary and then National Program Director. He assisted Bayard Rustin with organizing the 1963 March on Washington. As National Program Director of CORE, Hill coordinated the route 40 desegregation of restaurants, the Waldorf campaign, and illustrated the civil rights demonstration that took place at the 1964 Republican National Convention.

From 1964 to 1967, Norman Hill served as the Legislative Representative and Civil Rights Liaison of the Industrial Union department of the AFL–CIO. He was involved in the issue of raising minimum wage and the labor delegation on the Selma to Montgomery marches against racial discrimination in politics and voting in the Southern United States.

In 1967, Hill became active in the A. Philip Randolph Institute. Hill began as Associate Director, but he later became Executive Director and finally President. As Associate Director, Hill coordinated and organized the Memphis March in 1968 after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. In his career at the A. Philip Randolph Institute, Hill created over two hundred local chapters of this organization across the United States.[44]

Tom Kahn

Tom Kahn was a leader of SDUSA, who made notable contributions to the civil rights movement and to the labor movement.

Civil rights

Kahn helped Rustin organize the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington and the 1958 and 1959 Youth March for Integrated Schools.[45] As a white student at historically black Howard University, Kahn and Norman Hill helped Rustin and A. Philip Randolph to plan the 1963 March on Washington, at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech.[46][47] Kahn's role in the civil rights movement was discussed in the eulogy by Rachelle Horowitz.[37]

Support of Solidarity

When he became an assistant to the President of the AFL–CIO from 1972–1986, Kahn developed an expertise in international affairs.

Kahn was deeply involved with supporting the Polish labor movement.[48] The trade union Solidarity (Solidarność) began in 1980. The Soviet-backed communist regime headed by General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared martial law in December 1981. Lane Kirkland appointed Kahn to organize the AFL–CIO's support of Solidarity. Politically, the AFL–CIO supported the twenty-one demands of the Gdansk workers by lobbying to stop further U.S. loans to Poland unless those demands were met. Materially, the AFL–CIO established the Polish Workers Aid Fund, which raised almost $300,000 by 1981.[48] These funds purchased printing presses and office supplies. The AFL–CIO donated typewriters, duplicating machines, a minibus, an offset press and other supplies requested by Solidarity.[50][48]

The AFL–CIO sought approval in advance from Solidarity's leadership to avoid jeopardizing their position with unwanted or surprising American help.[48][49][37] On September 12, Lech Walesa welcomed international donations with this statement: "Help can never be politically embarrassing. That of the AFL–CIO, for example. We are grateful to them. It was a very good thing that they helped us. Whenever we can, we will help them, too".[51] Kahn explained the AFL–CIO position in a 1981 debate:

Solidarity made its needs known,[52] with courage, with clarity, and publicly. As you know, the AFL–CIO responded by establishing a fund for the purchase of equipment requested by Solidarity[52] and we have raised about a quarter of a million dollars for that fund.

This effort has elicited from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and Bulgaria the most massive and vicious propaganda assault on the AFL–CIO [...] in many, many years. The ominous tone of the most recent attacks leaves no doubt that if the Soviet Union invades, it shall cite the aid of the AFL-CIO as evidence of outside anti-Socialist intervention[52] aimed at overthrowing the Polish state.[53]

All this is by way of introducing the AFL–CIO's position on economic aid to Poland. In formulating this position, our first concern was to consult our friends in Solidarity [...]. We did consult with them [...] and their views are reflected in the statement unanimously adopted by the AFL–CIO Executive Council.

The AFL–CIO will support additional aid to Poland only if it is conditioned on the adherence of the Polish government to the 21 points of the Gdansk Agreement.[52] Only then could we be assured that the Polish workers will be in a position to defend their gains and to struggle for a fair share of the benefits of Western aid.[54]

In testimony to the Joint Congressional Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Kahn suggested policies to support the Polish people, in particular by supporting Solidarity's demand that the communist regime finally establish legality, by respecting the twenty-one rights guaranteed by the Polish constitution.[55]

The AFL–CIO provided the most aid to Solidarity, but substantial additional aid was provided by Western-European labor unions, including the United Kingdom's Trades Union Congress and especially the Swedish Trade Union Confederation.[56]

Criticism of AFL–CIO

The AFL–CIO's support enraged the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. Its support worried the Carter administration, whose Secretary of State Edmund Muskie told Kirkland that the AFL–CIO's continued support of Solidarity could trigger a Soviet invasion of Poland.[57][56] After Kirkland refused to withdraw support to Solidarity, Muskie met with the Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobyrnin,to clarify that the AFL–CIO's aid did not have the support of the United States government.[56]

Aid through the 1980s

Later, the National Endowment for Democracy provided $1.7 million for Solidarity, which was transferred via the AFL–CIO. In both 1988 and 1989, the Congress allocated $1 million yearly to Solidarity via the AFL–CIO.[50] In total, the AFL–CIO channeled 4 million dollars to Solidarity.[50][58]

Sandra Feldman

Sandra Feldman was an American civil rights activist, educator and labor leader who served as president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) from 1997 to 2004.[59][60] On January 22, 1999, she helped to organize and was the keynote speaker at the SDUSA workshop on "American Labor in the New Economy: A Day of Dialogue".

Socialist activism

She became active in socialist politics and the civil rights movement.[60] When she was 17 years old, she met civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who became her mentor and close friend. During her early years in the civil rights movement, Feldman worked to integrate Howard Johnson's restaurants in Maryland. She soon became employment committee chairwoman of the Congress of Racial Equality in Harlem. She also participated in several Freedom Rides and was arrested twice.[59]

Teaching

Upon graduation from Brooklyn College in 1962, Feldman worked for six months as a substitute third-grade teacher in East Harlem. She continued to be active in the civil rights movement, working to desegregate Howard Johnson restaurants in Maryland.[60] She participated in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was organized by Rustin and his associates. From 1963 to 1966, Feldman matriculated in a master's degree program in literature at New York University. While in graduate school, Feldman worked as a fourth-grade teacher at Public School 34 on the New York City's Lower East Side. She immediately joined the American Federation of Teachers, which had only one other member at the school. When New York City teachers won collective bargaining rights in 1960, she organized the entire school staff within a year.[60] During this time, Feldman became an associate of Albert Shanker, then an organizer for the United Federation of Teachers.[59]

United Federation of Teachers

In 1966, Shanker—now executive director of the UFT—hired Feldman as a full-time field representative on the recommendation of Rustin. Over the next nine years, Feldman became the union's executive director and oversaw its staff. She was elected its secretary (the second-most powerful position in the local) in 1983.[59]

After just two years on the UFT staff, Feldman played a crucial role in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike. The city of New York had designated the Ocean Hill-Brownsville area of Brooklyn as one of three decentralized school districts in an effort to give the minority community more say in school affairs.[60] The crisis began when the Ocean Hill-Brownsville governing board fired 13 teachers for allegedly sabotaging the decentralization experiment. Shanker demanded that specific charges be filed and the teachers given a chance to defend themselves in due process proceedings.[59][60]

A protracted fight erupted between those in the community who supported the Ocean Hill-Brownsville board and those supported the UFT. Many supporters of the local school board resorted to racial invective. Shanker was branded a racist, and many African-Americans accused the UFT of being "Jewish-dominated". Feldman was often at the center of the strike.[61] The UFT emerged from the crisis more powerful than ever and Feldman's hard work, good political judgment and calm demeanor won her widespread praise within the union.[59][60] Shanker was elected president of the AFT in 1974, but he retained his post as UFT President. In 1986, Shanker retired as UFT President and Feldman was elected president.[59][60]

UFT President after Shanker

Feldman was known for being a quiet yet very effective leader of the UFT. She fought school system chancellors and mayors both, winning significantly higher wages and benefits as well as improved working conditions for her members. She lobbied so fiercely for Bernard Gifford as New York City schools chancellor that Robert F. Wagner Jr., President of the New York City Board of Education, threatened to resign unless Feldman backed off and he was given a free hand.[59][60]

She was instrumental in helping David Dinkins win election as mayor of New York in 1989 by using union members and resources to build a winning electoral coalition of black and white voters.[60] However, once mayor Dinkins stalled on signing a new contract with the teachers' union and Feldman rarely criticized Dinkins publicly for his actions, but she kept the UFT out of Dinkins' 1993 re-election. Dinkins lost in a tight race to Rudy Giuliani.[59]

American Federation of Teachers

Feldman had been elected an AFT vice president in 1974,[62] serving on the national union's executive council and the executive council's executive committee.[59]

After Shanker died in February 1997, Feldman won election as the AFT President in July 1998, becoming the union's first female president since 1930. Feldman re-emphasized the AFT's commitment to educational issues. She also renewed the union's focus on organizing: During her tenure, the AFT grew by more than 160,000 new members (about 17 percent). With Feldman as President, in 2002 AFT delegates approved a four-point plan: 1) building a "culture of organizing" throughout the union, 2) enhancing the union's political advocacy efforts, 3) engaging in a series of publicity, legislative, funding and political campaigns to strengthen the institutions in which AFT members work; and 4) recommitting the AFT to fostering democratic education and human rights at home and abroad. Feldman moved quickly to ensure that the plan was implemented.[59]

In May 1997, Feldman was elected to the AFL–CIO executive council and appointed to the executive council's executive committee. During her tenure at the head of the AFT, Feldman also served as a vice president of Education International and was a board member of the International Rescue Committee and Freedom House.[59]

Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook was an American pragmatic philosopher known for his contributions to public debates. A student of John Dewey, Hook continued to examine the philosophy of history, of education, politics and of ethics. He was known for his criticisms of totalitarianism and fascism. A pragmatic social democrat, Hook sometimes cooperated with conservatives, particularly in opposing communism. After World War II, he argued that members of conspiracies, like the Communist Party USA and other Leninist conspiracies, ethically could be barred from holding offices of public trust.[63] Hook gave the keynote speech to the July 17–18, 1976 convention of SDUSA.[30]

For the Social Democrat, democracy is not merely a political concept but a moral one. It is democracy as a way of life. What is "democracy as a way of life." It is a society whose basic institutions are animated by an equality of concern for all human beings, regardless of class, race, sex, religion, and national origin, to develop themselves as persons to their fullest growth, to be free to live up to their desirable potentials as human beings. It is possible for human beings to be politically equal as voters but yet so unequal in educational, economic, and social opportunities, that ultimately even the nature of their political equality is affected.

When it comes to the principled defense of freedom, and to opposition to all forms of totalitarianism, let it be said that to its eternal credit, the organized labor movement in the United States, in contradiction to all other sectors of American life, especially in industry, the academy and the churches, has never faltered, or trimmed its sails. Its dedication to the ideals of a free society has been unsullied. Its leaders have never been Munich-men of the spirit.

I want to conclude with a few remarks about the domestic scene and the role of Social Democrats, U.S.A. in it. We are not a political party with our own candidates. We are not alone in our specific programs for more employment, more insurance, more welfare, less discrimination, less bureaucratic inefficiency. Our spiritual task should be to relate these programs and demands to the underlying philosophy of democracy, to express and defend those larger moral ideals that should inform, programs for which we wish to develop popular support.We are few in number and limited in influence. So was the Fabian Society of Great Britain. But in time it reeducated a great political party and much of the nation. We must try to do the same.

Penn Kemble

Penn Kemble was an American political activist and a founding member of SDUSA. He supported free labor-unions and democracy in the United States and internationally and so was active in the civil rights movement, the labor movement and the social democratic opposition to communism. He founded organizations including Negotiations Now!, Frontlash and Prodemca. Kemble was appointed to various government boards and institutions throughout the 1990s, eventually becoming the Acting Director of the U.S. Information Agency under President Bill Clinton.[64][65] After moving to New York, Kemble stood out as a neatly dressed, muscular Protestant youth in an urban political setting that was predominantly Catholic and Jewish. He worked at The New York Times, but was fired for refusing to cross a picket line during a typesetters' strike.[64] A leader in the East River chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, Kemble helped to organize a non-violent blockade of the Triborough Bridge during rush hour to raise consciousness among suburbanites of the lives of Harlem residents.[64] Kemble was a founder of Negotiation Now!, a group which called for an end to the bombing of North Vietnam and a negotiated settlement of the Vietnam War.[64] He was opposed to a unilateral withdrawal of American forces from Vietnam.

In 1972, Kemble was a founder the Coalition for a Democratic Majority (CDM), an association of centrist Democrats that opposed the "new politics" liberalism exemplified by Senator George McGovern, who suffered the worst defeat of a presidential candidate in modern times, despite the widespread dislike of Nixon.[65] Kemble was Executive Director of CDM from 1972–1976, at which time he left to become a special assistant and speechwriter for Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan.[64] He remained with Moynihan until 1979. Concerned about the direct and indirect role of the Communist Party USA and of sympathizers of Marxist–Leninist politics in the American peace movement and in the National Council of Churches, Kemble helped found the Institute on Religion and Democracy. From 1981 until 1988, Kemble was the President of the Committee for Democracy in Central America (PRODEMCA), which opposed the Sandinistas and related groups in Central America.[64][65]

Kemble supported the Bill Clinton's campaign for the presidency. During the Presidency of Bill Clinton, he served first in 1993 as the Deputy Director and then in 1999 as Acting Director of the United States Information Agency.[64][65] He was also made a special representative of Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright to the Community of Democracies Initiative.[66]

In 2001, Kemble was appointed to the International Broadcasting Bureau by President George W. Bush.[65] Kemble also became the Washington, D.C. representative of Freedom House and in his last years he was especially involved in supporting peace efforts in the Middle East. Secretary of State Colin L. Powell appointed Kemble to be the Chairman of the International Eminent Persons Group on Slavery, Abduction and Forced Servitude in Sudan.[65] Despite being diagnosed with brain cancer, Kemble spent his last months organizing a conference on the contributions of Sidney Hook, the late pragmatic philosopher and SDUSA spokesperson; Carl Gershman took over the leadership of the conference after Kemble's cancer made it impossible for him to continue.

Carl Gershman

Carl Gershman was the Executive Director of the SDUSA[32] from 1975 to 1980.[67] After having served as the Representative to the United Nations Committee on human rights during the first Reagan administration,[68][69] Carl Gershman has served as the President of the National Endowment for Democracy.[70] After the Polish people overthrew communism, their elected government awarded the Order of the Knight's Cross to Carl Gershman[70] and posthumously the Order of the White Eagle to AFL–CIO President Lane Kirkland.[71]

Hiatus and re-foundation

Following the death of the organization's Notesonline editor Penn Kemble of cancer on 15 October 2005,[72] SDUSA lapsed into a state of organizational hiatus, with no further issues of the online newsletter produced or updates to the group's website made.[73]

Following several years of inactivity, an attempt was subsequently made to revive SDUSA. In 2008, a group composed initially mostly of Pennsylvania members of SDUSA emerged, determined to re-launch the organization.[74] A re-founding convention of the SDUSA was held May 3, 2009, at which a National Executive Committee was elected.[75]

Owing to factional disagreements, a group based in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and the newly elected National Executive Committee parted company, with the former styling itself as the Social Democrats, USA – Socialist Party USA[76] and the latter as Social Democrats, USA.[77]

Two additional conventions took place since the 2009 reformation, an internet teleconference on September 1, 2010 featuring presentations by guest speakers Herb Engstrom of the California Democratic Party Executive Committee and Roger Clayman, Executive Director of the Long Island Labor Federation;[78] and a convention held August 26–27, 2012, in Buffalo, New York, with a keynote address delivered by Richard Lipsitz, executive director of Western New York Labor Federation.[79]

Controversies

Anti-communism

Michael Harrington charged that its "obsessive anti-communism" rendered SDUSA politically conservative.[80] In contrast, Harrington's DSOC and DSA criticized Marxism–Leninism, but he opposed many defense-and-diplomatic policies against the Soviet Union and its Eastern Bloc. Harrington voiced admiration for German Chancellor Willy Brandt's Ostpolitik which sought to reduce Western distrust of and hostility towards the Eastern Bloc and so entice the Soviet Union reciprocally to reduce its aggressive military posture.[81][82]

Max Shachtman and alleged Trotskyism

SDUSA leaders have served in the administrations of Presidents since the 1980 and the service of some members in Republican administrations has been associated with controversy. SDUSA members like Gershman were called "State Department socialists" by Massing (1987), who wrote that the foreign policy of the Reagan administration was being run by Trotskyists, a claim that was called a "myth" by Lipset (1988, p. 34).[68] This "Trotskyist" charge has been repeated and even widened by journalist Michael Lind in 2003 to assert a takeover of the foreign policy of the George W. Bush administration by former Trotskyists.[83] Lind's "amalgamation of the defense intellectuals with the traditions and theories of "the largely Jewish-American Trotskyist movement [in Lind's words]" was criticized in 2003 by University of Michigan professor Alan M. Wald,[84] who had discussed Trotskyism in his history of "the New York intellectuals".[85] SDUSA and allegations that "Trotskyists" subverted Bush's foreign policy have been mentioned by "self-styled" paleoconservatives (conservative opponents of neoconservatism).[86]

Harrington and Tom Kahn had been associated with Max Shachtman, a Marxist theorist who had broken with Leon Trotsky[87] because of his criticism of the Soviet Union as being a totalitarian class-society after having supported Trotsky in the 1930s.[88][89] Although Schachtman died in 1972 before the Socialist Party was renamed as SDUSA, Shachtman's ideas continued to influence the Albert Shanker and The American Federation of Teachers, which was often associated with SDUSA members. Decades later, conflicts in the AFL–CIO were roughly split in 1995 along the lines of the conflict between the "Shachtmanite Social Democrats and the Harringtonite Democratic Socialists of America, with the Social Democrats supporting Kirkland and Donahue and the Democratic Socialists supporting Sweeney".[90][91]

Alleged conservatism or neoconservatism

Some SDUSA members have been called "right-wing social democrats",[92] a taunt according to Wattenberg.[29]

SDUSA members supported Solidarity, the independent labor-union of Poland. The organizer of the AFL–CIO's support for Solidarity, SDUSA's Tom Kahn, criticized Jeane Kirkpatrick's "Dictatorships and Double Standards", arguing that democracy should be promoted even in the countries dominated by Soviet Communism.[93] In 1981, leading Social Democrats and some moderate Republicans wanted to use economic aid to Poland as leverage to expand the freedom of association in 1981, whereas Caspar Weinberger and neoconservative Jeane Kirkpatrick preferred to force the communist government of Poland to default on its international payments so they would lose credibility.[94] Kahn argued for his position in a 1981 debate with neoconservative Norman Podhoretz, who like Kirkpatrick and Weinberger opposed all credits.[49][95] In 1982, Kirkpatrick called similarly for Western assistance to Poland to be used to help Solidarity.[96]

Some of SDUSA's former members have been called neoconservatives.[97] Justin Vaisse listed five SDUSA associates as "second-generation neoconservatives" and "so-called Shachtmanites", including "Penn Kemble, Joshua Muravchik, [...] and Bayard Rustin".[98] Throughout his life, Penn Kemble called himself a social democrat and objected to being called a neoconservative.[64] Kemble and Joshua Muravchik were never followers of Max Shachtman. On the contrary, Kemble was recruited by a non-Shachtmanite professor, according to Muravchik, who wrote: "Although Shachtman was one of the elder statesmen who occasionally made stirring speeches to us, no YPSL [Young People's Socialist League] of my generation was a Shachtmanite".[99] Besides objecting to being called a "neoconservative", Kemble "sharply criticized the Bush administration's approach on [Iraq]. 'The distinction between liberation and democratization, which requires a strategy and instruments, was an idea never understood by the administration,' he told the New Republic", wrote The Washington Post in Kemble's obituary.[64]

Former member Joshua Muravchik

Joshua Muravchik has identified himself as a neoconservative.[100] When Muravhchik appeared at the 2003 SDUSA conference, he was criticized by SDUSA members:[19][101]

Rachelle Horowitz, another Social Democrats, USA, luminary and an event organizer, called Muravchik's comments "profoundly disturbing" — both his use of "us and them" rhetoric and the term "evil." The existence of evil in the world was something Horowitz was happy to concede, she said from the floor. But it was a word incapable of clear political definition and thus a producer of muddle rather than clarity, zeal rather than political action. Then Herf jumped in with similar criticisms. And then Berman. And Ibrahim. And before long, more or less everyone else in the room. There was still something, it seemed, that separated them from the neocons who hovered over the proceedings both as opponents and inspirations. Muravchik wanted to pull them somewhere most of the attendees — and organizers — were unwilling to go.[101]

Among Joshua Muravchick's SDUSA critics was his own father Emanuel Muravchik (a Norman Thomas socialist).[19][102][103] His mother was too upset with Joshua's Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism to attend the discussion.[102] On the other hand, Joshua Muravchik was called a "second-generation neoconservative" by Vaisse.[98]

Conventions

| Convention | Location | Date | Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 National Conference | Hopewell Junction, New York | September 21–23, 1973 | From registration ad, New America, July 30, 1973, p. 7. |

| 1974 National Convention | New York City | September 6–8, 1974 | 125 delegates, keynote speaker Walter Laqueur. Per New America, August 20, 1974, p. 8. |

| 1976 National Convention | New York City | July 17–18, 1976 | 500 delegates and observers, keynote speaker Sidney Hook. Per New America, August–September 1976, p. 1. |

| 1978 National Convention | New York City | September 8–10, 1978 | Introductory report by Carl Gershman. Per New America, October 1978, p. 1. |

| 1980 National Convention | New York City | November 21–23, 1980 | Per New America, December 1980, p. 1. |

| 1982 National Convention | Washington, D.C. | December 3–5, 1982 | Keynote speech by Albert Shanker. Dates per New America, October 1982, p. 8. |

| 1985 National Convention | Washington, D.C. | June 14–16, 1985 | Keynote speech by Alfonso Robelo. Per New America, November–December 1985, p. 6. |

| 1987 National Convention | |||

| 1990 National Convention | |||

| 1994 National Convention |

After reorganization

| Convention | Location | Date | Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 Reorganization Convention | May 3, 2009 | ||

| 2010 Convention | Internet teleconference | September 1, 2010 | |

| 2012 National Convention | Buffalo, New York | August 26–27, 2012 | Keynote speech by Richard Lipsitz, Executive Director of Western New York Labor Federation. |

| 2014 Convention | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | October 23–24, 2014 |

Prominent members

Notes

- "Principles". Social Democrats USA. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Hacker, David (2008–2010). "Heritage". Social Democrats USA. Retrieved 10 February 2020. "While concentrating on developing social democratic programs for the here and now, we have not given up our vision of the new socialist society that incremental change would eventually bring. We are still committed to the vibrant democratic socialist movement of the near future and our socialist vision of the far future beyond our lifetime and our children’s lifetime. [...] We view the terms "social democracy" and "democratic socialism" as being interchangeable."

- "Socialist Party now the Social Democrats, U.S.A." The New York Times. December 31, 1972. p. 36. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, Tough Liberal: Albert Shanker and the Battles Over Schools, Unions, Race and Democracy (Columbia University Press, August 13, 2013), p. 157–158.

- Gerald Sorin, The Prophetic Minority: American Jewish Immigrant Radicals, 1880–1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985; p. 155.

- Anonymous (27 December 1972). "Young Socialists open parley; to weigh 'New Politics' split". The New York Times. p. 25.

- Anonymous (1 January 1973). "'Firmness' urged on Communists: Social Democrats reach end of U.S. Convention here". The New York Times. p. 11.

- O'Rourke (1993, pp. 195–196): O'Rourke, William (1993). "L: Michael Harrington". Signs of the literary times: Essays, reviews, profiles, 1970–1992'. The Margins of Literature (SUNY Series). SUNY Press. pp. 192–196. ISBN 0-7914-1681-X. Originally: O'Rourke, William (13 November 1973). Michael Harrington: Beyond Watergate, Sixties, and reform. SoHo Weekly News. 3. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9780791416815.

- Busky 2000, pp. 165. Busky, Donald F. (2000). Democratic socialism: A global survey. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96886-1.

- Rustin wrote the following reports:

- Civil rights: the true frontier New York, N.Y.: Donald Press, 1963

- From protest to politics: the future of the civil rights movement New York: League for Industrial Democracy, 1965

- The labor-Negro coalition, a new beginning [Washington? D.C. : American Federationist?, 1968

- Conflict or coalition?: the civil rights struggle and the trade union movement today New York, A. Philip Randolph Institute, 1969.

- Rustin wrote the following reports:

- The Watts "Manifesto" & the McCone report. New York, League for Industrial Democracy 1966

- Separatism or integration, which way for America?: a dialogue (with Robert Browne) New York, A. Philip Randolph Educational Fund, 1968

- Black studies: myths & realities (contributor) New York, A. Philip Randolph Educational Fund, 1969

- Three essays New York, A. Philip Randolph Institute, 1969

- A word to black students New York, A. Philip Randolph Institute, 1970

- The failure of black separatism New York, A. Philip Randolph Institute, 1970

- Bloodworth (2013, p. 147)

- Fraser, C. Gerald (September 7, 1974). "Socialists seek to transform the Democratic Party" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 11.

- These positions had been advanced by organizations like "Negotiations Now!" since the 1960s.

- Gershman, Carl (3 November 1980). "Totalitarian menace (Controversies: Detente and the left after Afghanistan)". Society. 18 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1007/BF02694835. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 189883991.

- "The View from Washington". Asian Affairs. 6 (2): 134–135. November–December 1978. doi:10.1080/00927678.1978.10553935. JSTOR 30171704.

- Gershman, Carl (May 1978). "After the dominoes fell". Commentary. SD papers. 3.

- Meyerson, Harold (Fall 2002). "Solidarity, Whatever". Dissent. 49 (4): 16. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010.

- Social Democrats, USA (1973), The American challenge: A social-democratic program for the seventies, New York: SDUSA

- Mahler, Jonathan (19 November 1997), "Labor's crisis—and its opportunity", The Wall Street Journal

- "Freedom, Economic Justice Themes of SD Convention," New America [New York], vol. 13, no. 15 (Aug.-Sept. 1976), pg. 1.

- "Social Democracy Faces Crucial Era," New America [New York], vol 17, no. 11 (December 1980), pg. 1.

- "Rita Freedman New SD Director," New America [New York], vol. 17, no. 2 (Feb. 1980), pg. 12.

- "Wanted: Dues Cheaters" (ad), New America [New York], vol. 20, no. 5 (September–October 1983), pg. 7.

- Aldon Morris, The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Change (New York: The Free Press, 1994)

-

- Maurice Isserman. If I Had a Hammer...The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (Basic Books, 1987). ISBN 0-465-03197-8.

- America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, Maurice Isserman, and Michael Kazin, third ed. (2000; Oxford University Press, 2007). ISBN 0-19-516047-9.

- Hamby (2003, p. 25, footnote 5): Hamby, Alonzo L. (2003). "Is there no democratic left in America? Reflections on the transformation of an ideology". Journal of Policy History. 15: 3–25. doi:10.1353/jph.2003.0003. S2CID 144126978.

- Wattenberg, Ben (April 22, 1992). "A man whose ideas helped change the world". Baltimore Sun. Syndicated: (Thursday April 23, 1993). "Remembering a man who mattered". The Indiana Gazette p. 2 (pdf format). Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Hook, Sidney (1976), The social democratic prospect: Social democracy and America, New York: Social Democrats, USA

- "Labor Hall of Fame Honoree (1989): A. Philip Randoph". United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original on May 10, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- Rustin, Bayard; Gershman, Carl (1978), Africa, Soviet imperialism and the retreat of American power, SD papers, 2, New York: Social Democrats, USA

- Rustin's selected writings have been republished as Time on two crosses: the collected writings of Bayard Rustin (San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2003). Rustin's writings had appeared in an earlier collection>

- Bayard Rustin – Who Is This Man Archived May 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, State of the Reunion, radio show, aired February 2011 on NPR, 1:40–2:10, accessed March 16, 2011.

- Rustin wrote the following reports:

- The revolution in the South" Cambridge, Mass. : Peace Education Section, American Friends Service Committee, 1950s

- Report on Montgomery, Alabama New York: War Resisters League, 1956

- A report and action suggestions on non-violence in the South New York: War Resisters League, 1957

- Life Magazine, September 6, 1963.

- Horowitz (2007)

- Rustin, Bayard (February 1965). "From protest to politics: The future of the civil rights movement". Commentary.

- Kennedy, Randall (29 September 2003). "From protest to patronage". The Nation.

- Wilson's The Declining Significance of Race won the American Sociological Association's Sydney Spivack Award. In The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions (1978), Wilson argues that the significance of race is waning, and an African-American's class is comparatively more important in determining his or her life chances. His The Truly Disadvantaged, which was selected by the editors of The New York Times Book Review as one of the 16 best books of 1987, and received The Washington Monthly Annual Book Award and the Society for the Study of Social Problems' C. Wright Mills Award. In The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy (1987), Wilson was one of the first to enunciate at length the "spatial mismatch" theory for the development of a ghetto underclass. As industrial jobs disappeared in cities in the wake of global economic restructuring, and hence urban unemployment increased, women found it unwise to marry the fathers of their children, since the fathers would not be breadwinners. His When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor, which was selected as one of the notable books of 1996 by the editors of The New York Times Book Review and received the Sidney Hillman Foundation Award. His The Bridge Over the Racial Divide: Rising Inequality and Coalition Politics reaffirms the need for a coalition strategy, as Rustin suggested. In Wilson's most recent book, More Than Just Race: Being Black and Poor in the Inner City (2009), he directs his attention to the overall framing of pervasive, concentrated urban poverty of African Americans. He asks the question, "Why do poverty and unequal opportunity persist in the lives of so many African Americans?" In response, he traces the history and current state of powerful structural factors impacting African Americans, such as discrimination in laws, policies, hiring, housing, and education. Wilson also examines the interplay of structural factors and the attitudes and assumptions of African Americans, European Americans, and social science researchers. In identifying the dynamic influence of structural, economic, and cultural factors, he argues against either/or politicized views of poverty among African Americans that either focus blame solely on cultural factors or only on unjust structural factors. He tries "to demonstrate the importance of understanding not only the independent contributions of social structure and culture, but also how they interact to shape different group outcomes that embody racial inequality." Wilson's goal is to "rethink the way we talk about addressing the problems of race and urban poverty in the public policy arena" (PDF).

- Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou (June 26, 2009). "Gays Are the New Niggers". Killing the Buddha. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- South Africa: is peaceful change possible? a report (contributor) New York, New York Friends Group, 1984

- Staff. "Calm Battler for Rights; Norman Spencer Hill Jr.", The New York Times, September 14, 1964. Accessed February 19, 2011. "Norman Hill was born in Summit, N.J."

-

- African American Registry (2005).

- Norman Hill, an Activist for Black Labor. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Blair Speech (2003). Bayard Rustin: The Whole Story. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Electrical Workers Minority Caucus (2000). Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- National Black Caucus of State Legislators (2006). Builder Awards: Norman Hill. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- Stephen H. Sachs (January 16, 2011). "Haverford College – Racism remembered – Discovering that even the small wounds of prejudice can linger decades later". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

The barber chair was empty as I entered. The barber... ignored the skinny black kid who was sitting quietly, waiting patiently. That kid was Norman Hill, a sophomore, one of the tiny number of African-Americans in Haverford's student body then.

- Isserman, Maurice If I had a hammer New York, Basic Books 1987

- Jervis Anderson, A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait (1973; University of California Press, 1986). ISBN 978-0-520-05505-6

-

- Anderson, Jervis. Bayard Rustin: Troubles I've Seen (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997).

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63 (New York: Touchstone, 1989).

- Carbado, Devon W. and Donald Weise, editors. Time on Two Crosses: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin(San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2003). ISBN 1-57344-174-0

- D’Emilio, John. Lost Prophet: Bayard Rustin and the Quest for Peace and Justice in America (New York: The Free Press, 2003).

- D'Emilio, John. Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2004). ISBN 0-226-14269-8

- Shevis (1981, p. 31).

- (Kahn & Podhoretz 2008)

- Kahn, Tom; Podhoretz, Norman (Summer 2008). sponsored by the Committee for the Free World and the League for Industrial Democracy, with introduction by Midge Decter and moderation by Carl Gershman, held at the Polish Institute for Arts and Sciences, New York City in March 1981. "How to support Solidarnosc: A debate" (PDF). Democratiya (Merged with Dissent in 2009). 13: 230–261. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2011.

- Puddington (2005):

Puddington, Arch (2005). "Surviving the underground: How American unions helped solidarity win". American Educator (Summer). Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- Puddington (2005) quotes "Polish Strike Leader Thanks U.S. Labor", Associated Press, September 12, 1980.

- Emboldening added.

- Opening statement by Tom Kahn in Kahn & Podhoretz (2008, p. 234)

- Opening statement by Tom Kahn in Kahn & Podhoretz (2008, p. 235)

- Kahn, Tom (March 3, 1982). "Moral duty". Society. 19 (3): 51. doi:10.1007/BF02698967. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 189883236.

- Shevis (1981, p. 32)

- Puddington (2008) wrote:

"Kirkland's embrace of Solidarity brought him into immediate conflict with the Carter administration. Despite the administration's avowed commitment to human rights, Edmund Muskie, secretary of state, decided that quiet diplomacy was the most prudent course to follow in the Polish crisis. He summoned Kirkland to his office for lunch on September 3, 1980, during which he gave a 'negative assessment' of the Polish aid fund that the AFL-CIO had just launched and declared that the federation's open support for Solidarity could be 'deliberately misinterpreted' by the Kremlin in order to justify military intervention. Muskie was not alone in deploring labor's Polish initiative. In a New York Times column, Flora Lewis called the Workers Aid Fund 'most unfortunate.' Flora Lewis, "Let the Poles Do It," New York Times, September 5, 1980.]"

- "The AFL-CIO had channeled more than $4 million to it, including computers, printing presses, and supplies" according to Horowitz (2005).

-

- Almanac of Famous People. 88th ed. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale Group, 2003. ISBN 0-7876-7535-0

- Berger, Joseph. "Sandra Feldman, Scrappy and Outspoken Labor Leader for Teachers, Dies at 65." The New York Times. September 20, 2005.

- Carter, Barbara. Pickets, Parents, and Power: The Story Behind the New York City Teachers' Strike. New York: Citation Press, 1971. ISBN 0-590-09480-7

- Farber, M.A. "Molded in Schools, She Helps Mold Them." The New York Times. March 7, 1991.

- "Feldman Elected AFT President." New York Teacher. May 19, 1997.

- Greenhouse, Steven. "Feldman to Succeed Shanker, Teachers' Union Officials Say." The New York Times. April 29, 1997.

- "Sandra Feldman, 65; Ex-President of Teachers Union." Los Angeles Times. September 20, 2005.

- Yan, Ellen. "Ex-Teachers Union Leader Feldman Dies." Newsday. September 20, 2005.

- Berger, Joseph (September 20, 2005). "Sandra Feldman, scrappy and outspoken labor leader for teachers, dies at 65". The New York Times.

- Carter, Pickets, Parents, and Power, 1971.

- "walter p. reuther library/AFT ward - people of the aft". reuther.wayne.edu.

- Hook was a public intellectual for more than five decades:

- Cotter, Matthew J., ed., 2004, Sidney Hook Reconsidered, Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

- Kurtz, Paul, ed., 1968, Sidney Hook and the Contemporary World, New York: John Day and Co.

- Kurtz, Paul, ed., 1983, Sidney Hook: Philosopher of democracy and humanism, Buffalo: Prometheus Books. [This festschrift for Sidney Hook's eightieth birthday contains four essays on Hook's person and writings.]

- Capaldi, Nicholas, 1983, “Sidney Hook: A Personal Portrait,” in Kurtz 1983, pp. 17–27.

- Konvitz, Milton R., 1983, “Sidney Hook: Philosopher of the Moral-Critical Intelligence,” in Kurtz 1983, pp. 3–6.

- Kristol, Irving, “Life with Sidney: A Memoir,” in Kurtz 1983.

- Kurtz, Paul, 1983a, “Preface: The Impact of Sidney Hook in the Twentieth Century,” in Kurtz 1983.

- Levine, Barbara, ed. Sidney Hook: A Checklist of Writings, Southern Illinois University, 1989.

- Ryan, Alan, 2002, Foreword to Sidney Hook, Sidney Hook on Pragmatism, Democracy, and Freedom: The Essential Essays, (Robert B. Talisse and Robert Tempio (eds.), Amherst: Prometheus Books, pp. 9–10.

- Sidorsky, David (2003). "Charting the Intellectual Career of Sidney Hook: Five Major Steps". Partisan Review. 70 (2): 324–342.

- Out of Step, Harper & Row, 1987. Autobiography

- Sidney Hook on Pragmatism, Freedom, and Democracy: The Essential Essays, ed. Robert B. Talisse and Robert Tempio, Prometheus Books, 2002.

- Holley, Joe (October 19, 2005). "Political activist Penn Kemble dies at 64". The Washington Post.

- "Penn Kemble: Dapper Democratic Party activist whose influence extended across the spectrum of US politics (21 January 1941 – 15 October 2005)". The Times. London. October 31, 2005.

- "Social democrat neocon (sic.)", Washington Times, October 18, 2005.

- Dale Reed, "Register of the Carl Gershman Papers, 1962–1984," Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University, 1999; pg. 2.

- "A 1987 article in The New Republic described these developments as a Trotskyist takeover of the Reagan administration" wrote Lipset (1988, p. 34).

- Nossiter, Bernard D. (March 3, 1981). "New team at U.N.: Common roots and philosophies". The New York Times (Late City final ed.). section A, p. 2, col. 3.

- "Meet Our President". National Endowment for Democracy. Archived from the original on April 26, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- Lane Kirkland was awarded posthumously the highest Polish award Archived May 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, the Order of the White Eagle.

- "Political Activist Penn Kemble Dies at 64," The Washington Post, October 19, 2005, pg. B07.

- See: Social Democrats, USA, official website, www.socialdemocratsusa.org/ Retrieved May 26, 2011, currently broken.

- David Hacker, "Heritage: Learning from Our Past," www.socialistcurrents.org/ Retrieved Feb. 27, 2014.

- "Organization," www.socialistcurrents.org/ Retrieved Feb. 27, 2014.

- Social Democrats-Socialist Party USA official website, www.socialdemocratsusa.org/ Retrieved May 26, 2011 (Dead link).

- Social Democrats, USA, official website, www.socialdemocrats.org/ Retrieved Feb. 27, 2014.

- "2010 National Convention," Socialist Currents, www.socialistcurrents.org/

- "2012 Convention Report," Socialist Currents, www.socialistcurrents.org/

- Bloodworth (2013, p. 148)

- Bloodworth, Jeffrey (2013). Losing the center: The decline of American liberalism, 1968–1992. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813142296.

- Isserman, The Other American, pp. 351–352.

- As co-chairman of DSA, Michael Harrington wrote that Willy Brandt "launched his famous ostpolitik (Eastern policy), and moved toward detente with the Soviets and Eastern Europeans—a strategy that was to win him the Nobel Peace Prize. [...] Disaster came in 1974. There was a spy scandal—a member of Brandt's inner circle turned out to be an East German agent—and the chancellor resigned his office.Harrington, Michael (March 31, 1987). "Willy Brandt May Even Yet Manage Resurrection No. 5". Los Angeles Times.

- Lind, Michael (7 April 2003). "The weird men behind George W. Bush's war". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- Wald, Alan (27 June 2003). "Are Trotskyites Running the Pentagon?". History News Network.

- Wald, Alan M. (1987). The New York intellectuals: The rise and decline of the anti-Stalinist left from the 1930s to the 1980s'. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4169-3.

- King, William (2004). "Neoconservatives and 'Trotskyism'". American Communist History. 3 (2): 247–266. doi:10.1080/1474389042000309817. ISSN 1474-3906. S2CID 162356558.

King, Bill (March 22, 2004). "Neoconservatives and Trotskyism. The question of 'Shachtmanism'". Enter Stage Right: Politics, Culture, Economics (3): 1–2. ISSN 1488-1756.

- Muravchik (2006). Addressing the allegation that SDUSUA was a "Trotskyist" organization, Muravchik wrote that in the early 1960s, two future members of SDUSA, Tom Kahn and Paul Feldman:

"became devotees of a former Trotskyist named Max Shachtman—a fact that today has taken on a life of its own. Tracing forward in lineage through me and a few other ex-YPSL's [members of the Young Peoples Socialist League] turned neoconservatives, this happenstance has fueled the accusation that neoconservatism itself, and through it the foreign policy of the Bush administration, are somehow rooted in 'Trotskyism.' I am more inclined to laugh than to cry over this, but since the myth has traveled so far, let me briefly try once more, as I have done at greater length in the past, to set the record straight.[See "The Neoconservative Cabal," Commentary, September 2003] The alleged connective chain is broken at every link. The falsity of its more recent elements is readily ascertainable by anyone who cares for the truth—namely, that George Bush was never a neoconservative and that most neoconservatives were never YPSL's. The earlier connections are more obscure but no less false. Although Shachtman was one of the elder statesmen who occasionally made stirring speeches to us, no YPSL of my generation was a Shachtmanite. What is more, our mentors, Paul and Tom, had come under Shachtman’s sway years after he himself had ceased to be a Trotskyite.

- "A saving remnant". New Press. January 8, 2011 – via Internet Archive.

- Isserman, Maurice (January 8, 2000). "The other American : the life of Michael Harrington". New York : PublicAffairs – via Internet Archive.

- Kahlenberg, Richard D. (August 30, 2007). "Tough Liberal: Albert Shanker and the Battles Over Schools, Unions, Race, and Democracy". Columbia University Press – via Google Books.

- In 1982 Harrington's Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee reformed as the Democratic Socialists of America.

- John Haer, "Reviving Socialism," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 1, 1982. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- Vaisse, op cit. p. 91.

- Kahn, Tom (July 1985), January 1985 speech to the 'Democratic Solidarity Conference' organized by the Young Social Democrats (YSD) under the auspices of the Foundation for Democratic Education, "Beyond the double standard: A social democratic view of the authoritarianism versus totalitarianism debate" (PDF), New America, Social Democrats, USACS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reprinted: Kahn, Tom (2008) [1985]. "Beyond the double standard: A social democratic view of the authoritarianism versus totalitarianism debate" (PDF). Democratiya (Merged into Dissent in 2009). 12 (Spring): 152–160.

- Domber , with revision and typeset

- Gershman, Carl (August 29, 2011). "Remarks by Carl Gershman at a photo exhibition commemorating the 30th anniversary of the founding of Solidarity (The phenomenon of Solidarity: Pictures from the history of Poland, 1980–1981; Woodrow Wilson Center)" (html). Washington D.C.: National Endowment for Democracy. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jeane J. Kirkpatrick (1988). Political and moral dimensions. Transaction Publishers. p. 164ff. ISBN 9780887380990.

- Matthews, Dylan (August 28, 2013). "Meet Bayard Rustin, the gay socialist pacifist who planned the 1963 March on Washington" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- Vaïsse, Justin (January 8, 2010). "Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement". Harvard University Press – via Google Books.

- Muravchik, Joshua (January 2006). "Comrades". Commentary Magazine. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- Muravchik, Joshua (November–December 2006), "Operation comeback" (PDF), Foreign Policy

- Joshua Micah Marshall, "Debs’s Heirs Reassemble To Seek Renewed Role as Hawks of Left" The Jewish Daily Forward, May 23, 2003.

- Muravchik, Joshua (8 May 2002). "Joshua Muravchik revisits communism: Where socialism lives on". National Review Online (May 2, 2003 10:45 A.M. ed.).

- Muravchik, Manny (2002). Socialism in my life and my life in socialism (html). Private (hosted by Social Democrats, USA). A Letter to my children, grandchildren and beyond and to my comrades, ex-comrades and anti-comrades gathering on May Day 2002. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

References

- Bernstein, Carl (February 24, 1992). "The holy alliance: Ronald Reagan and John Paul II; How Reagan and the Pope conspired to assist Poland's Solidarity movement and hasten the demise of Communism (Cover story)". Time (U.S. ed.): 28–35.

- Bloodworth, Jeffrey (2013). Losing the center: The decline of American liberalism, 1968–1992. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813142296.

- Domber, Gregory F. (2008). Supporting the revolution: America, democracy, and the end of the Cold War in Poland, 1981–1989 (Ph.D. dissertation (12 September 2007), George Washington University). pp. 1–506. ISBN 978-0-549-38516-5. Winner of the "2009 Betty M. Unterberger Prize for Best Dissertation on United States Foreign Policy from the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations". Revised and incorporated in Domber, Gregory F. (2014). Empowering Revolution: America, Poland, and the End of the Cold War. The New Cold War History. University of North Carolina Press books. ISBN 9781469618517.

- Gershman, Carl (3 November 1980). "Totalitarian menace (Controversies: Detente and the left after Afghanistan)". Society. 18 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1007/BF02694835. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 189883991.

- Harrington, Michael (3 November 1980). "Nuclear threat (Controversies: Detente and the left after Afghanistan)". Society. 18 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1007/BF02694836. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 189885851.

- Horowitz, Rachelle (2007). "Tom Kahn and the Fight for Democracy: A Political Portrait and Personal Recollection" (PDF). Democratiya (Merged with Dissent in 2009). 11 (Winter): 204–251.

- Kahn, Tom; Podhoretz, Norman (2008). "How to support Solidarnosc: A debate ('Sponsored by the Committee for the Free World and the League for Industrial Democracy, with introduction by Midge Decter and moderation by Carl Gershman, and held at the Polish Institute for Arts and Sciences, New York City in March 1981')" (PDF). Democratiya (Merged with Dissent in 2009). 13 (Summer): 230–261.

- Lipset, Seymour (4 July 1988). "Neoconservatism: Myth and reality". Society. 25 (5): 29–37. doi:10.1007/BF02695739. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 144110677.

- Massing, Michael (1987). "Trotsky's orphans: From Bolshevism to Reaganism". The New Republic: 18–22.

- Muravchik, Joshua (January 2006). "Comrades". Commentary Magazine. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- Puddington, Arch (2005). "Surviving the underground: How American unions helped solidarity win". American Educator (Summer). Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- Shevis, James M. (Summer 1981). "The AFL-CIO and Poland's Solidarity". World Affairs. 144 (1): 31–35. JSTOR 20671880.

Publications

- Social Democrats, USA (December 1972) [copyright 1973]. The American challenge: A social-democratic program for the seventies. New York: S.D. U.S.A. and YPSL. "The following program was adopted at the Social Democrats, U.S.A. and Young People's Socialist League conventions at the end of December, 1972".

- Hook, Sidney (2005) [17–18 July 1976], originally entitled "The social democratic prospect: Social democracy and America", "The social democratic prospect" (PDF), Democratiya, Archived by Dissent, 3 (Winter): 63–76, Alternative source.

- Hook, Sidney; Rustin, Bayard; Gershman, Carl; Kemble, Penn (1978). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. SD Papers. 1. New York: Social Democrats, USA. Reprinted from Commentary (April 1978) pp. 29–71.

- Bayard Rustin and Carl Gershman, Africa, Soviet imperialism and the retreat of American power. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1978. (SD papers #2).

- Gershman, Carl (May 1978). "After the dominoes fell". Commentary. SD papers. 3.

- Carl Gershman The world according to Andrew Young. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1978. (SD papers #4).

- Leszek Kołakowski and Sidney Hook, The social democratic challenge. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1978. (SD papers #5).

- Carl Gershman, Selling them the rope: Business and the Soviets. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1979. (SD papers #6).

- Lane Kirkland and Rita Freedman, Building on the past for the future. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1981.

- Social Democrats, USA: Standard bearers for freedom, democracy, and economic justice. New York: Social Democrats, USA, n.d. [1980s].

- A challenge to the Democratic Party. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1983.

- Alfonso Robelo, The Nicaraguan democratic struggle: Our unfinished revolution. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1983. (SD papers #8).

- Scabs renamed, permanent replacements. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1990.

- On foreign policy and defense. Washington, D.C. : Social Democrats, USA, 1990.

- SD, USA statement on the economy. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1991.

- Child labor, US style. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1991.

- Child labor, an international abuse. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1991.

- John T. Joyce, Expanding economic democracy. New York: Social Democrats, USA, 1991.

- Rita Freedman, Does America need a social democratic movement? Washington, DC: Social Democrats, USA, 1993.

- Why America needs a social democratic movement. Washington, DC : Social Democrats, USA, 1993.

- The future of socialism. San Jose, CA: San Francisco Bay Area Local of Social Democrats, USA, 1994.

Further reading

- Chenoweth, Eric (October 2010), AFL-CIO support for Solidarity: Political, financial, moral, 1718 M Street, NW, No. 147, Washington DC 20036, USA: Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe (IDEE)CS1 maint: location (link).