Misumalpan languages

The Misumalpan languages (also Misumalpa or Misuluan) are a small family of languages spoken by indigenous peoples on the east coast of Nicaragua and nearby areas. The name "Misumalpan" was devised by John Alden Mason and is composed of syllables from the names of the family's three members Miskito, Sumo languages and Matagalpan.[1] It was first recognized by Walter Lehmann in 1920. While all the languages of the Matagalpan branch are now extinct, the Miskito and Sumu languages are alive and well: Miskito has almost 200,000 speakers and serves as a second language for speakers of other Indian languages on the Mosquito Coast. According to Hale,[2] most speakers of Sumu also speak Miskito.

| Misumalpan | |

|---|---|

| Misuluan | |

| Geographic distribution | Nicaragua |

| Linguistic classification | Macro-Chibchan ? Hokan ?

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | misu1242 |

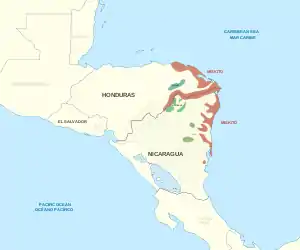

Historical (dotted) and current (colored) distribution of the Misumalpan languages | |

External relations

Kaufman (1990) finds a connection with Macro-Chibchan to be "convincing", but Misumalpan specialist Ken Hale considered a possible connection between Chibchan and Misumalpan to be "too distant to establish".[2] Jolkesky (2017:45-54) notes lexical resemblances between various Misumalpan and Hokan languages, which he interprets as evidence of either genetic relatedness or prehistoric language contact.[3]

Classification

- Miskito – nearly 200,000 speakers, mainly in the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region of Nicaragua, but including some in Honduras.

- Sumalpan languages:

- Sumo languages – some 8,000 speakers along the Huaspuc River and its tributaries, most in Nicaragua but some in Honduras. Many of them have shifted to Miskito.

- Mayangna - dominant variety of the Sumo family

- Ulwa

- Matagalpan

- Cacaopera † – formerly spoken in the Morazán department of El Salvador; and

- Matagalpa † – formerly spoken in the central highlands of Nicaragua and the El Paraíso department of Honduras

- Sumo languages – some 8,000 speakers along the Huaspuc River and its tributaries, most in Nicaragua but some in Honduras. Many of them have shifted to Miskito.

Miskito became the dominant language of the Mosquito Coast from the late 17th century on, as a result of the people's alliance with the British Empire, which colonized the area. In northeastern Nicaragua, it continues to be adopted by former speakers of Sumo. Its sociolinguistic status is lower than that of the English-based creole of the southeast, and in that region, Miskito seems to be losing ground. Sumo is endangered in most areas where it is found, although some evidence suggests that it was dominant in the region before the ascendancy of Miskito. The Matagalpan languages are long since extinct, and not very well documented.

All Misumalpan languages share the same phonology, apart from phonotactics. The consonants are p, b, t, d, k, s, h, w, y, and voiced and voiceless versions of m, n, ng, l, r; the vowels are short and long versions of a, i, u.

Loukotka (1968)

Below is a full list of Misumalpan language varieties listed by Loukotka (1968), including names of unattested varieties.[4]

- Mosquito group

- Mosquito / Miskito - language spoken on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua and Honduras, Central America. Dialects are:

- Kâbô - spoken on the Nicaraguan coast.

- Baldam - spoken on the Sandy Bay and near Bimuna.

- Tawira / Tauira / Tangwera - spoken on the Prinzapolca River.

- Wanki - spoken on the Coco River and on the Cabo Gracias a Dios.

- Mam / Cueta - spoken on the left bank of the Coco River, Honduras.

- Chuchure - extinct dialect once spoken around Nombre de Dios, Panama. (Unattested.)

- Ulua / Wulwa / Gaula / Oldwaw / Taulepa - spoken on the Ulúa River and Carca River, Nicaragua.

- Sumu / Simou / Smus / Albauin - spoken on the Prinzapolca River, Nicaragua. Dialects are:

- Bawihka - spoken on the Banbana River.

- Tawihka / Táuaxka / Twaca / Taga - spoken between the Coco River and Prinzapolca River.

- Panamaca - spoken between the Pispis River, Waspuc River, and Bocay River.

- Cucra / Cockorack - spoken on the Escondido River and Siqui River.

- Yosco - spoken on the Tuma River and Bocay River. (Unattested.)

- Matagalpa group

- Matagalpa / Chontal / Popoluca - extinct language once spoken from the Tumo River to the Olama River, Nicaragua.

- Jinotega / Chingo - extinct language once spoken in the villages of Jinotega and Danlí, Nicaragua. (only several words.)

- Cacaopera - spoken in the villages of Cacaopera and Lislique, El Salvador.

Proto-language

Below are Proto-Misumalpan reconstructions by Adolfo Constenla Umaña (1987):[5]

| No. | Spanish gloss (original) | English gloss (translated) | Proto-Misumalpan |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | abuela | grandmother | titiŋ |

| 2 | abuelo | grandfather | *nini |

| 3 | acostarse | lie down | *udaŋ |

| 4 | agua | water | *li |

| 5 | amarillo | yellow | *lalalh |

| 6 | árbol | tree | *ban |

| 7 | arena | sand | *kawh |

| 8 | atar | tie | *widi |

| 9 | ayote | pumpkin | |

| 10 | beber | drink (v.) | *di |

| 11 | boca | mouth | *ta |

| 12 | bueno | good | *jam- |

| 13 | búho | owl | *iskidi |

| 14 | cantárida | Spanish fly | *mada |

| 15 | caracol | snail | *suni |

| 16 | caramba | interjection | *anaj |

| 17 | casa | house | *u |

| 18 | cocer | cook (tr.) | *bja |

| 19 | cocerse | cook (intr.) | *wad |

| 20 | colibrí | hummingbird | *sud |

| 21 | cuarta persona | fourth person | *-ni |

| 22 | chica de maíz | corn girl | *sili |

| 23 | chile | chile | *kuma |

| 24 | dar | give | *a |

| 25 | dinero | money | *lihwan |

| 26 | dormir | sleep | *jabu |

| 27 | dos | two | *bu |

| 28 | esposa | wife | *maja |

| 29 | estar | to be | *da |

| 30 | exhortativo-imperativo plural | plural exhortative-imperative verb | *-naw |

| 31 | flecha | arrow | |

| 32 | formativo de verbo intransitivo | formative intransitive verb | *-wa |

| 33 | gallinácea silvestre | wild fowl | |

| 34 | garrapata | tick | *mata |

| 35 | garza | heron | *udu |

| 36 | guardar | watch (v.) | *ubak |

| 37 | guatusa | Dasyprocta punctata | *kjaki |

| 38 | gusano | worm | *bid |

| 39 | hierro | iron | *jasama |

| 40 | humo | smoke | |

| 41 | interrogativo | interrogative | *ma |

| 42 | interrogativo | interrogative | *ja |

| 43 | ir | go | *wa |

| 44 | jocote | Spondias purpurea | *wudak |

| 45 | lejos | far | *naj |

| 46 | lengua | tongue | *tu |

| 47 | luna | moon | *wajku |

| 48 | llamarse | be called, named | *ajaŋ |

| 49 | maíz | corn | *aja |

| 50 | maduro | mature | *ahawa |

| 51 | matapalo | strangler fig | *laka |

| 52 | mentir | lie | *ajlas |

| 53 | mujer | woman | *jwada |

| 54 | murciélago | bat | *umis |

| 55 | nariz | nose | *nam |

| 56 | negativo (sufijo verbal) | negative (verbal suffix) | *-san |

| 57 | nube | cloud | *amu |

| 58 | ocote | Pinus spp. | *kuh |

| 59 | oír | hear | *wada |

| 60 | oler (intr.) | smell (intr.) | *walab |

| 61 | oreja | ear | *tupal |

| 62 | orina | urine | *usu |

| 63 | perezoso | lazy | *saja |

| 64 | pesado | heavy | *wida |

| 65 | piedra | stone | *walpa |

| 66 | piel | skin | *kutak |

| 67 | piojo | louse | |

| 68 | pléyades | Pleiades | *kadu |

| 69 | podrido | rotten | |

| 70 | meter | place, put | *kan |

| 71 | pozol | pozol | *sawa |

| 72 | presente (sufijo verbal) | present (verbal suffix) | *ta |

| 73 | primera persona (sufijo) | first person (suffix) | *-i |

| 74 | primera persona (sufijo) | first person (suffix) | *-ki |

| 75 | red | net | *wali |

| 76 | rodilla | knee | *kadasmak |

| 77 | rojo | red | *paw |

| 78 | sangre | blood | *a |

| 79 | segunda persona (sufijo) | second person (suffix) | *-ma |

| 80 | tacaní (tipo de abeja) | tacaní (type of bee) | *walaŋ |

| 81 | tepezcuintle (paca) | Cuniculus paca | *uja |

| 82 | tercer persona (sufijo) | third person (suffix) | *-ka |

| 83 | teta | nipple | *tja |

| 84 | teta | nipple | *su |

| 85 | tigre | jaguar | |

| 86 | tos | cough | *anaŋ |

| 87 | tú | you (sg.) | *man |

| 88 | verde | green | *saŋ |

| 89 | viento | wind | *win |

| 90 | yerno | son-in-law | *u |

| 91 | yo | I | *jam |

| 92 | zacate | grass | *tun |

| 93 | zopilote | vulture | *kusma |

| 94 | zorro hediondo | skunk | *wasala |

Notes

- Hale & Salamanca 2001, p. 33

- Hale & Salamanca 2001, p. 35

- Jolkesky, Marcelo. 2017. Lexical parallels between Hokan and Misumalpan.

- Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo (1987). "Elementos de Fonología Comparada de las Lenguas Misumalpas," Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica 13 (1), 129-161.

Bibliography

- Benedicto, Elena (2002), "Verbal Classifier Systems: The Exceptional Case of Mayangna Auxiliaries." In "Proceedings of WSCLA 7th". UBC Working Papers in Linguistics 10, pp. 1–14. Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Benedicto, Elena & Kenneth Hale, (2000) "Mayangna, A Sumu Language: Its Variants and Its Status within Misumalpa", in E. Benedicto, ed., The UMOP Volume on Indigenous Languages, UMOP 20, pp. 75–106. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts.

- Colette Craig & Kenneth Hale, "A Possible Macro-Chibchan Etymon", Anthropological Linguistics Vol. 34, 1992.

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo (1987) "Elementos de Fonología Comparada de las Lenguas Misumalpas," Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica 13 (1), 129-161.

- Constenla Umaña A. (1998). "Acerca de la relación genealógica de las lenguas lencas y las lenguas misumalpas," Communication presented at the First Archeological Congress of Nicaragua (Managua, 20–21 July), to appear in 2002 in Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica 28 (1).

- Hale, Ken. "El causativo misumalpa (miskitu, sumu)", In Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca "Julio de Urquijo" 1996, 30:1-2.

- Hale, Ken (1991) "Misumalpan Verb Sequencing Constructions," in C. Lefebvre, ed., Serial Verbs: Grammatical, Comparative, and Cognitive Approaches, John Benjamins, Amsterdam.

- Hale, Ken and Danilo Salamanca (2001) "Theoretical and Universal Implications of Certain Verbal Entries in Dictionaries of the Misumalpan Languages", in Frawley, Hill & Munro eds. Making Dictionaries: Preserving indigenous Languages of the Americas. University of California Press.

- Jolkesky, Marcelo (2017) "On the South American Origins of Some Mesoamerican Civilizations". Leiden: Leiden University. Postdoctoral final report for the “MESANDLIN(G)K” project. Available here.

- Koontz-Garboden, Andrew. (2009) "Ulwa verb class morphology", In press in International Journal of American Linguistics 75.4. Preprint here: http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000639

- Ruth Rouvier, "Infixation and reduplication in Misumalpan: A reconstruction" (B.A., Berkeley, 2002)

- Phil Young and T. Givón. "The puzzle of Ngäbére auxiliaries: Grammatical reconstruction in Chibchan and Misumalpan", in William Croft, Suzanne Kemmer and Keith Denning, eds., Studies in Typology and Diachrony: Papers presented to Joseph H. Greenberg on his 75th birthday, Typological Studies in Language 20, John Benjamins 1990.

External links

| Wiktionary has a list of reconstructed forms at Appendix:Proto-Misumalpan reconstructions |

- FDL bibliography (general, but search specific language names)

- Ulwa Language home page

- Ulwa Language Home Page bibliography

- Moskitia bibliography

- The Misumalpan Causative Construction – Ken Hale

- Theoretical and Universal Implications of Certain Verbal Entries in Dictionaries of the Misumalpan Languages – Ken Hale

- The Joy of Tawahka – David Margolin

- Matagalpa Indigena – some words of Matagalpan

- Andrew Koontz-Garboden's web page (with links to papers on Ulwa)