Culture of England

The culture of England is defined by the cultural norms of England and the English people. Owing to England's influential position within the United Kingdom it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate English culture from the culture of the United Kingdom as a whole.[1] However, since Anglo-Saxon times, England has had its own unique culture, apart from Welsh, Scottish or Northern Irish culture.

| Culture of England |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Rich in history and culture and birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, many of the world's most celebrated scientists, inventions, and thinkers originated from England. England has also played an important role in cinema, literature, technology, engineering, democracy, social science and mathematics.

Manor houses, gardens, rolling countryside, and green landscapes are common English cultural symbols. A rose and oak tree are considered national symbols of England. Humour, tradition, and good manners are characteristics commonly associated with being English.[2]

Architecture

English architecture begins with the architecture of the Anglo-Saxons. At least fifty surviving English churches are of Anglo-Saxon origin, although in some cases the Anglo-Saxon part is small and much-altered. All except one timber church are built of stone or brick, and in some cases show evidence of reused Roman work. The architectural character of Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical buildings ranges from Coptic-influenced architecture in the early period, through Early Christian basilica influenced architecture, to (in the later Anglo-Saxon period) an architecture characterized by pilaster-strips, blank arcading, baluster shafts and triangular-headed openings. Almost no secular work remains above ground.

Following the Norman Conquest Romanesque architecture (known here as Norman architecture) superseded Anglo-Saxon architecture; later there was a period of transition into English Gothic architecture (of which there are three periods, Early English, Decorated, and Perpendicular). In early modern times there was an influence from Renaissance architecture until by the 18th century. Gothic forms of architecture had been abandoned and various classical styles were adopted. During the Victorian period Neo-Gothic architecture was preferred for many types of buildings but this did not continue into the 20th century.

Other buildings such as cathedrals and parish churches are associated with a sense of traditional Englishness, as is often the palatial 'stately home'. Many people are interested in the English country house and the rural lifestyle, evidenced by the number of visitors to properties managed by English Heritage and the National Trust.

Landscape gardening as developed by Capability Brown set an international trend for the English garden. Gardening, and visiting gardens, are regarded as typically English pursuits. Each period in English history has its own architecturally significance and have influenced the setting and society of each English historic period in the later modern period.

.jpg.webp) Tudor

Tudor Jacobean

Jacobean Georgian

Georgian Regency

Regency Victorian

Victorian

Seaside piers

Following the building of the world's first seaside pier at Ryde, the pier became fashionable at seaside resorts in England during the Victorian era, peaking in the 1860s with 22 being built in that decade.[3] A symbol of the typical English seaside holiday, by 1914 more than 100 pleasure piers were located around the UK coast. Regarded as being among the finest Victorian architecture, there are still a significant number of seaside piers of architectural merit still standing, although some have been lost, including two at Brighton in East Sussex and one at New Brighton in the Wirral.[4] Two piers, Brighton's now derelict West Pier and Clevedon Pier, were Grade 1 listed. The Birnbeck Pier in Weston-super-Mare is the only pier in the world linked to an island. The National Piers Society gives a figure of 55 surviving seaside piers in England and Wales.[5]

Gardens

Landscape gardening as developed by Capability Brown set an international trend for the English garden. Gardening, visiting gardens, and a love for gardens are regarded as typically English pursuits. The English garden presented an idealized view of nature. At large country houses, the English garden usually included lakes, sweeps of gently rolling lawns set against groves of trees, and recreations of classical temples, Gothic ruins, bridges, and other picturesque architecture, designed to recreate an idyllic pastoral landscape.

By the end of the 18th century the English garden was being imitated by the French landscape garden, and as far away as St. Petersburg, Russia, in Pavlovsk, the gardens of the future Emperor Paul. It also had a major influence on the form of the public parks and gardens which appeared around the world in the 19th century.[6] The English landscape garden was centred on the English country house and stately homes.

Today, some large-scale English gardens and English landscape gardens are popular visitor cultural attractions managed by both English Heritage and the National Trust. The Chelsea Flower Show is held every year.[7]

Cathedrals

Many cathedrals of England are ancient, dating from as far back as around 700. They are a major aspect of the country's artistic heritage.

Medieval Christianity included the veneration of saints, with pilgrimages to places where particular saints' relics were interred. The possession of the relics of a popular saint was a source of funds for an individual church, as the faithful made donations and benefices in the hope that they might receive spiritual aid, a blessing or a healing from the presence of the physical remains of the holy person. Among those churches to benefit in particular were St Albans Abbey, which contained the relics of England's first Christian martyr; Ripon with the shrine of its founder St. Wilfrid; Durham, which was built to house the body of Saints Cuthbert of Lindisfarne and Aidan; Ely with the shrine of St. Ethelreda; Westminster Abbey with the magnificent shrine of its founder St. Edward the Confessor; at Chichester, the remains of St. Richard; and at Winchester, those of St. Swithun.

All these saints brought pilgrims to their churches, but among them the most renowned was Thomas Becket, the late Archbishop of Canterbury, assassinated by henchmen of King Henry II in 1170. As a place of pilgrimage Canterbury was, in the 13th century, second only to Santiago de Compostela. In the 1170s Gothic architecture was introduced at Canterbury and Westminster Abbey. Over the next 400 years it developed in England, sometimes in parallel with and influenced by Continental forms, but generally with great local diversity and originality.

Art and design

England has Europe's earliest and northernmost ice-age cave art.[8] Prehistoric art in England largely corresponds with art made elsewhere in contemporary Britain, but early medieval Anglo-Saxon art saw the development of a distinctly English style,[9] and English art continued thereafter to have a distinct character. English art made after the formation in 1707 of the Kingdom of Great Britain may be regarded in most respects simultaneously as art of the United Kingdom.

Medieval English painting, mainly religious, had a strong national tradition and was influential in Europe.[10] The English Reformation, which was antipathetic to art, not only brought this tradition to an abrupt stop but resulted in the destruction of almost all wall-paintings.[11][12] Only illuminated manuscripts now survive in good numbers.[13]

There is in the art of the English Renaissance a strong interest in portraiture, and the portrait miniature was more popular in England than anywhere else.[14] English Renaissance sculpture was mainly architectural and for monumental tombs.[15] Interest in English landscape painting had begun to develop by the time of the 1707 Act of Union.[16] English art was dominated by imported artists throughout much of the Renaissance, but in the 18th century a native tradition became much admired. It is considered to be typified by landscape painting, such as the work of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. Portraitists like Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds are also significant.

Pictorial satirist William Hogarth pioneered Western sequential art, and political illustrations in this style are often referred to as "Hogarthian".[17] Following Hogarth, political cartoons developed in England in the late 18th century under the direction of James Gillray. Regarded as one of the two most influential cartoonists (the other is Hogarth), Gillray has been referred to as the father of the political cartoon, with his satirical work calling the king (George III), prime ministers and generals to account.[18] The early 19th century saw the emergence of the Norwich school of painters, the first provincial art movement outside of London. Short-lived owing to sparse patronage and internal dissent, its prominent members were "founding father" John Crome (1768-1821), John Sell Cotman (1782-1842), James Stark (1794-1859), and Joseph Stannard (1797-1830).[19]

Landscape painting

In England, landscapes had initially been mostly backgrounds to portraits, typically suggesting the parks or estates of a landowner, though mostly painted in London by an artist who had never visited his sitter's rolling acres. The English tradition was founded by Anthony van Dyck and other mostly Flemish artists working in England, but in the 18th century the works of Claude Lorrain were keenly collected and influenced not only paintings of landscapes, but the English landscape gardens of Capability Brown and others.

In the 18th century, watercolour painting, mostly of landscapes, became an English specialty, with both a buoyant market for professional works, and a large number of amateur painters, many following the popular systems found in the books of Alexander Cozens and others. By the beginning of the 19th century the English artists with the highest modern reputations were mostly dedicated landscape painters, showing the wide range of Romantic interpretations of the English landscape found in the works of John Constable, J.M.W. Turner.

Portrait painting

The first famous native English portrait miniaturist is Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1537–1619), whose work was conservative in style but very sensitive to the character of the sitter; his best works are beautifully executed. The colours are opaque, and gold is used to heighten the effect, while the paintings are on card. They are often signed, and have frequently also a Latin motto upon them. Hilliard worked for a while in France, and he is probably identical with the painter alluded to in 1577 as Nicholas Belliart. Hilliard was succeeded by his son Lawrence Hilliard (died 1640); his technique was similar to that of his father, but bolder, and his miniatures richer in colour.[20]

Isaac Oliver and his son Peter Oliver succeeded Hilliard. Isaac (c. 1560–1617) was the pupil of Hilliard. Peter (1594–1647) was the pupil of Isaac. The two men were the earliest to give roundness and form to the faces they painted. They signed their best works in monogram, and painted not only very small miniatures, but larger ones measuring as much as 10 in × 9 in (250 mm × 230 mm). They copied for Charles I of England (1600-1649) on a small scale many of his famous pictures by the old masters.

Samuel Cooper (1609–1672) was a nephew and student of the elder Hoskins, and is considered the greatest English portrait miniaturist. He spent much of his time in Paris and Holland, and very little is known of his career. His work has a superb breadth and dignity, and has been well called life-size work in little. His portraits of the men of the Puritan epoch are remarkable for their truth to life and strength of handling. He painted upon card, chicken skin and vellum, and on two occasions upon thin pieces of mutton bone. The use of ivory was not introduced until long after his time. His work is frequently signed with his initials, generally in gold, and very often with the addition of the date.

During the Baroque and Rococo periods, the first major native portrait painters of the British school were English painters Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds, who also specialized in clothing their subjects in an eye-catching manner. Gainsborough's Blue Boy is one of the most famous and recognized portraits of all time, painted with very long brushes and thin oil color to achieve the shimmering effect of the blue costume.[21] Gainsborough was also noted for his elaborate background settings for his subjects.

Tourism and cultural landmarks

.jpg.webp)

Tourism plays a significant part in the economic life of England. In 2018, the United Kingdom as a whole was the world's 10th most visited country for tourists,[22] and 17 of the United Kingdom's 25 UNESCO World Heritage Sites fall within England.[23]

England is the largest of the four "home nations" that make up the United Kingdom. It is also the most populous of the four with almost 52 million inhabitants (roughly 84% of the total population of the UK). On the island of Great Britain, Scotland sits to the north of England and Wales is to the west. Northern Ireland (also part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland lie across the Irish Sea to west of England (and Wales). France and the Channel Islands are across the English Channel to the south, and to the east is the North Sea.

VisitEngland is the official tourist board for England. VisitEngland's stated mission is to build England's tourism product, raise Britain’s profile worldwide, increase the volume and value of tourism exports and develop England and Britain’s visitor economy.[24] In 2020, the Lonely Planet travel guide rated England as the second best country to visit that year, after Bhutan.[25]

A number of umbrella organisations are devoted to the preservation and public access of both natural and cultural heritage, including English Heritage and the National Trust. Membership with them, even on a temporary basis, gives priority free access to their properties thereafter.

English Heritage has a wide-ranging remit and manages more than 400 significant buildings and Monuments in England. They also maintain a register of thousands of listed buildings,[26] those which are considered of most importance to the historic and cultural heritage of the country.

Literature

English literature begins with Anglo-Saxon literature, which was written in Old English and produced such heroic epic works as Beowulf and the fragmentary The Battle of Maldon, the sombre and introspective The Seafarer and The Wanderer and the pious Dream of the Rood and The Order of the World. For many years, Latin and French were the preferred literary languages of England, but in the medieval period there was a flourishing of literature in Middle English; Geoffrey Chaucer is the most famous writer of this period. The Elizabethan era is sometimes described as the golden age of English literature, as numerous great poets were writing in English, and the Elizabethan theatre produced William Shakespeare, often considered the English national poet.

Due to the expansion of English into a world language during the British Empire, literature is now written in English across the world. Writers often associated with England or for expressing Englishness include Shakespeare (who produced two tetralogies of history plays about the English kings), Jane Austen, Arnold Bennett, and Rupert Brooke (whose poem "Grantchester" is often considered quintessentially English). Other writers are associated with specific regions of England; these include Charles Dickens (London), Thomas Hardy (Wessex), A. E. Housman (Shropshire), and the Lake Poets (the Lake District).

In a lighter vein, Agatha Christie's mystery novels are outsold only by Shakespeare and The Bible. Described as "perhaps the 20th century's best chronicler of English culture", the non-fiction works of George Orwell include The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), documenting his experience of working class life in the north of England.[27] Orwell's eleven rules for making tea appear in his essay "A Nice Cup of Tea", which was published in the London Evening Standard on 12 January 1946.[28]

In 2003 the BBC carried out a UK survey entitled The Big Read in order to find the "nation's best-loved novel" of all time, with works by English novelists J. R. R. Tolkien, Jane Austen, Philip Pullman, Douglas Adams and J. K. Rowling making up the top five on the list.[29]

Music

England has a long and rich musical history. The United Kingdom has, like most European countries, undergone a roots revival in the last half of the 20th century. English music has been an instrumental and leading part of this phenomenon, which peaked at the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s.

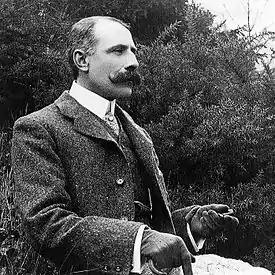

The achievements of the Anglican choral tradition following on from 16th-century composers such as Thomas Tallis, John Taverner and William Byrd have tended to overshadow instrumental composition. The semi-operatic innovations of Henry Purcell did not lead to a native operatic tradition, but George Frideric Handel found important royal patrons and enthusiastic public support in England. One of Handel's four Coronation Anthems, Zadok the Priest (1727), composed for the coronation of George II, has been performed at every subsequent British coronation, traditionally during the sovereign's anointing. The rapturous receptions afforded by audiences to visiting musical celebrities such as Haydn often contrasted with the lack of recognition for home-grown talent. However, the emergence of figures such as Edward Elgar and Arthur Sullivan in the 19th century showed a new vitality in English music. In the 20th century, Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett emerged as internationally recognised opera composers, and Ralph Vaughan Williams and others collected English folk tunes and adapted them to the concert hall. Cecil Sharp was a leading figure in the English folk revival. The Proms, an annual summer season of daily classical music concerts, is a significant event in British musical life.[30] The Last Night of the Proms features patriotic music.

Finally, a new trend emerged from Liverpool in 1962. The Beatles became the most popular musicians of their time, and in the composing duo of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, popularized the concept of the self-contained music act. Before the Beatles, very few popular singers composed the tunes they performed. The "Fab Four" opened the doors for other acts from England such as The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Cream, The Kinks, The Who, Eric Clapton, David Bowie, Queen, Elton John, The Hollies, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, Genesis, Dire Straits, Iron Maiden, The Police to the globe.

The Sex Pistols and The Clash were pioneers of punk rock. Some of England's leading contemporary artists include George Michael, Sting, Seal, Rod Stewart, The Smiths, The Stone Roses, Oasis, Blur, Radiohead, The Cure, Depeche Mode, Coldplay, Def Leppard, Muse, Arctic Monkeys, Amy Winehouse, Adele and Ed Sheeran.

Cinema

England (and the UK as a whole) has had a considerable influence on the history of the cinema, producing some of the greatest actors, directors and motion pictures of all time, including Alfred Hitchcock, Charlie Chaplin, David Lean, Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh, John Gielgud, Peter Sellers, Julie Andrews, Michael Caine, Gary Oldman, Helen Mirren, Kate Winslet and Daniel Day-Lewis. Hitchcock and Lean are among the most critically acclaimed of all-time.[33] Hitchcock's first thriller, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1926), helped shape the thriller genre in film, while his 1929 film, Blackmail, is often regarded as the first British sound feature film.[34]

Major film studios in England include Pinewood, Elstree and Shepperton. Some of the most commercially successful films of all time have been produced in England, including two of the highest-grossing film franchises (Harry Potter and James Bond).[35] Ealing Studios in London has a claim to being the oldest continuously working film studio in the world.[36] Famous for recording many motion picture film scores, the London Symphony Orchestra first performed film music in 1935.[37]

The BFI Top 100 British films includes Monty Python's Life of Brian (1979), a film regularly voted the funniest of all time by the UK public.[38] English producers are also active in international co-productions and English actors, directors and crew feature regularly in Hollywood films. Ridley Scott was among a group of English filmmakers, including Tony Scott, Alan Parker, Hugh Hudson and Adrian Lyne, who emerged from making 1970s UK television commercials.[39] The UK film council ranked David Yates, Christopher Nolan, Mike Newell, Ridley Scott and Paul Greengrass the five most commercially successful English directors since 2001.[40] Other contemporary directors from England include Sam Mendes, Guy Ritchie and Steve McQueen. Current actors include Tom Hardy, Daniel Craig, Benedict Cumberbatch and Emma Watson. Acclaimed for his motion capture work, Andy Serkis opened The Imaginarium Studios in London in 2011.[41] The visual effects company Framestore in London has produced some of the most critically acclaimed special effects in modern film.[42] Many successful Hollywood films have been based on English people, stories or events. The 'English Cycle' of Disney animated films include Alice in Wonderland, The Jungle Book, Robin Hood and Winnie the Pooh.[43]

Elizabethan Theatre

The peak of English drama and theatre is said to be the Elizabethan Age; a golden age in English history where the arts and creative work flourished. The first permanent English theatre, the Red Lion, opened in 1567[44] but it was a short-lived failure. The first successful theatres, such as The Theatre, opened in 1576. The establishment of large and profitable public theatres was an essential enabling factor in the success of English Renaissance drama.

Archaeological excavations on the foundations of the Rose and the Globe in the late 20th century showed that all the London theatres had individual differences, but their common function necessitated a similar general plan.[45] The public theatres were three stories high, and built around an open space at the centre. Usually polygonal in plan to give an overall rounded effect, although the Red Bull and the first Fortune were square. The three levels of inward-facing galleries overlooked the open centre, into which jutted the stage: essentially a platform surrounded on three sides by the audience. The rear side was restricted for the entrances and exits of the actors and seating for the musicians. The upper level behind the stage could be used as a balcony, as in Romeo and Juliet and Antony and Cleopatra, or as a position from which an actor could harangue a crowd, as in Julius Caesar.[46]

The playhouses were generally built with timber and plaster. Individual theatre descriptions give additional information about their construction, such as flint stones being used to build the Swan. Theatres were also constructed to be able to hold a large number of people.[47] One of the main uses of costume during the Elizabethan era was to make up for the lack of scenery, set, and props on stage. It created a visual effect for the audience, and it was an integral part of the overall performance.[48] Since the main visual appeal on stage were the costumes, they were often bright in colour and visually entrancing. Colours symbolized social hierarchy, and costumes were made to reflect that. For example, if a character was royalty, their costume would include purple. The colours, as well as the different fabrics of the costumes, allowed the audience to know the status of each character when they first appeared on stage.[49]

Costumes were collected in inventory. More often than not, costumes wouldn't be made individually to fit the actor. Instead, they would be selected out of the stock that theatre companies would keep. A theatre company reused costumes when possible and would rarely get new costumes made. Costumes themselves were expensive, so usually players wore contemporary clothing regardless of the time period of the play. The most expensive pieces were given to higher class characters because costuming was used to identify social status on stage. The fabrics within a playhouse would indicate the wealth of the company itself. The fabrics used the most were: velvet, satin, silk, cloth-of-gold, lace, and ermine.[50]

The growing population of London, the growing wealth of its people, and their fondness for spectacle produced a dramatic literature of remarkable variety, quality, and extent. Genres of the period included the history play, which depicted English or European history. Shakespeare's plays about the lives of kings, such as Richard III and Henry V, belong to this category, as do Christopher Marlowe's Edward II and George Peele's Famous Chronicle of King Edward the First. History plays dealt with more recent events, like A Larum for London which dramatizes the sack of Antwerp in 1576. Tragedy was a very popular genre. Marlowe's tragedies were exceptionally successful, such as Dr. Faustus and The Jew of Malta. The audiences particularly liked revenge dramas, such as Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy. The four tragedies considered to be Shakespeare's greatest (Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth) were composed during this period.

Comedies were common, too. A subgenre developed in this period was the city comedy, which deals satirically with life in London after the fashion of Roman New Comedy. Examples are Thomas Dekker's The Shoemaker's Holiday and Thomas Middleton's A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Though marginalised, the older genres like pastoral (The Faithful Shepherdess, 1608), and even the morality play (Four Plays in One, ca. 1608-13) could exert influences. After about 1610, the new hybrid subgenre of the tragicomedy enjoyed an efflorescence, as did the masque throughout the reigns of the first two Stuart kings, James I and Charles I.

Performing arts

Large outdoor music festivals in the summer and autumn are popular, such as Glastonbury, V Festival, Reading and Leeds Festivals. England was at the forefront of the illegal, free rave movement from the late 1980s, which led to pan-European culture of teknivals mirrored on the UK free festival movement and associated travelling lifestyle.[51] The most prominent opera house in England is the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden.[52] The Proms, a season of orchestral classical music concerts held at the Royal Albert Hall, is a major cultural event held annually.[52] The Royal Ballet is one of the world's foremost classical ballet companies, its reputation built on two prominent figures of 20th century dance, prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn and choreographer Frederick Ashton.

A staple of British seaside culture, the quarrelsome couple Punch and Judy made their first recorded appearance in Covent Garden, London in 1662.[53] The various episodes of Punch and Judy are performed in the spirit of outrageous comedy—often provoking shocked laughter—and are dominated by the anarchic clowning of Mr. Punch.[54] Regarded as British cultural icons, they appeared at a significant period in British history, with Glyn Edwards stating: "[Pulcinella] went down particularly well with Restoration British audiences, fun-starved after years of Puritanism. We soon changed Punch's name, transformed him from a marionette to a hand puppet, and he became, really, a spirit of Britain - a subversive maverick who defies authority, a kind of puppet equivalent to our political cartoons."[53]

The circus is a traditional form of entertainment in the UK. Chipperfield's Circus dates back more than 300 years in Britain, making it one of the oldest family circus dynasties.[55] Philip Astley is regarded as the father of the modern circus.[4] Following his invention of the circus ring in 1768, Astley's Amphitheatre opened in London in 1773.[4][56] As an equestrian master Astley had a skill for trick horse-riding, and when he added tumblers, tightrope-walkers, jugglers, performing dogs, and a clown to fill time between his own demonstrations – the modern circus was born.[57][58] The Hughes Royal Circus was popular in London in the 1780s. Pablo Fanque's Circus Royal, among the most popular circuses of Victorian England, showcased William Kite, which inspired John Lennon to write "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" on The Beatles' album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Joseph Grimaldi, the most celebrated of clowns from England is considered the father of modern clowning.[59]

Pantomime (often referred to as "panto") is a British musical comedy stage production, designed for family entertainment. It is performed in theatres throughout the UK during the Christmas and New Year season. The art originated in the 18th century with John Weaver, a dance master and choreographer at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London.[60] In 19th century England it acquired its present form, which includes songs, slapstick comedy and dancing, employing gender-crossing actors, combining topical humour with a story loosely based on a well-known fairy tale.[60] It is a participatory form of theatre, in which the audience sing along with parts of the music and shout out phrases to the performers, such as "It's behind you".[61]

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment popular from the early Victorian era to the mid 20th century. The precursor to variety shows of today, music hall involved a mixture of popular songs, comedy, speciality acts and variety entertainment. British performers who honed their skills at pantomime and music hall sketches include Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel, George Formby, Gracie Fields, Dan Leno, Gertrude Lawrence and Harry Champion.[62][63] British music hall comedian and theatre impresario Fred Karno developed a form of sketch comedy without dialogue in the 1890s, and Chaplin and Laurel were among the music hall comedians who worked for him.[64] A leading film producer stated; "Fred Karno is not only a genius, he is the man who originated slapstick comedy. We in Hollywood owe much to him."[65]

Heritage, museums and galleries

English Heritage is a governmental body with a broad remit of managing the historic sites, artefacts and environments of England. It is currently sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty is a charity which also maintains multiple sites. 17 of the 25 United Kingdom UNESCO World Heritage Sites fall within England.[66]

Some of the best known of these include Hadrian's Wall, Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites, Tower of London, Jurassic Coast, Westminster, Roman Baths in Bath, Saltaire, Ironbridge Gorge, and Studley Royal Park. The northernmost point of the Roman Empire, Hadrian's Wall, is the largest Roman artefact anywhere: it runs a total of 73 miles in northern England.[67]

London's British Museum hosts a collection of more than seven million objects[68] is one of the largest and most comprehensive in the world, sourced from every continent, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its beginning to the present.[69] The library has two of the four remaining copies of the original Magna Carta (the other two copies are held in Lincoln Castle and Salisbury Cathedral) and has a room devoted solely to them. The British Library Sound Archive has over six million recordings, many from the BBC Sound Archive, including Winston Churchill's wartime speeches.

The British Library in London is the national library and is one of the world's largest research libraries, holding over 150 million items in all known languages and formats; including around 25 million books.[70] The most senior art gallery is the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, which houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900.[71] The Tate galleries house the national collections of British and international modern art; they also host the famously controversial Turner Prize.[72] Most museums and art galleries are free to visit for all visitors.

A blue plaque, the oldest historical marker scheme in the world, is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the UK to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event.[73] The scheme was the brainchild of politician William Ewart in 1863 and was initiated in 1866.[73] It was formally established by the Society of Arts in 1867, and since 1986 has been run by English Heritage.[73]

The first plaque was unveiled in 1867 to commemorate Lord Byron at his birthplace, 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square, London. Examples that commemorate events include John Logie Baird's first demonstration of the television at 22 Frith Street, Westminster, W1, London, and the first sub 4-minute mile run by Roger Bannister on 6 May 1954 at Oxford University's Iffley Road Track.

Cuisine

Since the early modern era, the food of England has historically been characterised by its simplicity of approach, honesty of flavour, and a reliance on the high quality of natural produce.[74] This has resulted in a traditional cuisine which tended to avoid strong flavours, such as garlic, and also complex sauces which were commonly associated with Roman Catholic Continental affiliations.[75] Traditional meals have ancient origins, such as bread, cheese and onions,[76] popular today as the ploughman's lunch;[77] pottage and frumenty;[78] roasted and stewed meats; meat and game pies; and freshwater and saltwater fish. The 14th-century English cookbook, the Forme of Cury, contains recipes for these, and dates from the royal court of Richard II. French cuisine has influenced English cooking to some degree since the mid-17th century, although in England "the meal still centred on pies and joints of meat, as it had done there in medieval times. English cooking did not change much over the ages, whereas French food did".[79]

The last half century has seen significant changes in food manufacturing, retailing and consumption;[80] an interest in different international cuisines; and the establishment of large chains of restaurants, fast-food outlets, coffee shops and supermarkets. However, distinctively English dishes,[81] artisanal production, delicatessens, home cooking and traditional establishments such as pubs, cafes and tearooms remain widespread. The 1990s saw the rise of the gastropub, serving traditional English dishes, and farmers' markets. Food culture in England has been taken more seriously since the 1960s due to writers and broadcasters such as Derek Cooper, Lady Arabella Boxer (née Stuart), Matthew Fort, Jonathan Meades and Nigel Slater.[82]

Roast beef is a food traditionally associated with the English; the link was made famous by Henry Fielding's patriotic ballad "The Roast Beef of Old England", and William Hogarth's painting of the same name. Indeed, since the 18th century the phrase "les rosbifs" has been a popular French nickname for the English.[83] Lamb is eaten especially at Easter.[84] An English commentator wrote: “We have, throughout our history as a nation, had a weakness for meat in pastry which, while it is not unique, is a sort of hallmark of our taste.”[85] Pies appear in common English idioms such as "to eat humble pie", "as easy as pie", "pie in the sky" and "a slice of the pie". Suet is an ingredient in several traditional English dishes. Dumplings made with flour, suet and seasonings[86] and pearl barley[87] may be cooked with casseroles and stews. Potatoes are served roasted, boiled, baked, mashed, and as chips; popular varieties in England including King Edward, Jersey Royal, Charlotte potato,[88] and Maris Piper.[89]

Typical English main courses[90] include beefsteak (such as sirloin, rump, fillet, T-bone and rib eye), lamb shank,[91] pork and lamb chops[92] chicken and chips, gammon, egg and chips, steak and kidney pie and other variants of steak pie, chicken and mushroom pie, bacon and egg pie,[93] shepherd's pie,[94] cottage pie,[95] fish pie, Lancashire hotpot, scouse,[96] Beef Wellington, steak and kidney pudding, stuffed marrow[97] savoury bacon roll, boiled beef and carrots,[98] rissoles, faggots, liver and bacon in onion gravy,[99] Northumberland pan haggerty,[100] sausage and mash, and toad in the hole.[101] Butchers sell artisanal sausages, which are sometimes made from the meat of pedigree breeds such as Gloucester Old Spot pigs. English sausages generally contain about 70 per cent meat, bread rusk and seasonings.[102] Cumberland, Lincolnshire, Newmarket and Oxford sausages are regional varieties.[103] The best-known types of English ham are from Wiltshire and York. Game dealers sell venison and wild game, such as pheasant, partridge and grouse.[104] Jugged rabbit and hare are traditional dishes.

Sunday roast

A Sunday roast[105] comprises roast meat served with gravy, roast potatoes[106] and vegetables such as cauliflower, cabbage, carrots, parsnips, swede, spring greens, spinach, runner beans, broad beans, leeks[107] and garden peas. Courgettes became widely available in the late 1960s and broccoli first appeared in supermarkets in the late 1970s, initially as a seasonal item. Meats served as part of a Sunday roast include beef, typically a fore rib of beef, with Yorkshire puddings and horseradish sauce or English mustard;[108] lamb, typically a leg, shoulder or saddle of lamb, with mint sauce or redcurrant jelly; pork, typically leg, shoulder or loin of pork, with crackling and apple sauce; honey-glazed gammon with cloves and parsley sauce; and poultry, such as chicken, duck (e.g. Aylesbury duck)[109] and goose.[110]

Consumption of chicken increased from the 1950s when the introduction of poultry factories, pioneered in England by JB Eastwood Ltd. owned by John Bealby Eastwood,[111] significantly reduced the price.[112]

Christmas dinner

An English Christmas dinner traditionally consists of roast goose, duck, pheasant or (now most often) turkey,[113] cranberry sauce, bread sauce, stuffing, gravy, pigs in blankets, roast potatoes, chestnuts, Brussels sprouts and other vegetables.[114]

It is sometimes accompanied by cooked gammon and usually followed by Christmas pudding, traditionally made on stir-up Sunday, with rum or brandy butter, mince pies filled with mincemeat and Christmas cake.[115] Biscuits in the form of gingerbread men are associated with Christmas, as are imported oranges, which are traditionally placed in Christmas stockings.

Fish

The most popular types of fish in England, mainly imported through Grimsby,[116] are salmon, cod, haddock, tuna and prawns.[117] Fish and chips, sometimes served with mushy peas, are sold by fish and chip shops.[118] Brixham in Devon has the highest value catch in England;[119] other domestic fisheries include Cornwall and Hastings. Dover sole is so named because it could historically be sourced from the fishing port of Dover. Potted shrimps, prawn cocktail, whitebait, scallops and slices of smoked salmon, such as London Cure,[120] are starters served with a squeeze of lemon and brown bread. Oysters are cultivated along the east coast of England, for example at Whitstable. Crabs are particularly associated with the Norfolk town of Cromer. Samphire is collected in coastal areas and served with fish.

Savoury dishes, snacks, soups and sauces

Light meals and snacks include green salads served with salad cream,[121] cauliflower cheese, macaroni cheese, Welsh rarebit,[122] fishcakes, baked potatoes, cheese on toast, beans on toast, mushrooms on toast, spare ribs, Cornish pasties,[123] Scotch eggs,[124] sausage rolls, pork pies,[125] gala pie and bacon sandwiches. The sandwich was named after the Earl of Sandwich[126] and is very common as a lunchtime and picnic item with a wide range of fillings.[127] Stotties, filled with ham and pease pudding, are eaten particularly in the north-east of England. Asparagus is served with butter alone or with other ingredients such as eggs and ham; the English asparagus season runs from late April to the end of June.

A poll in 2011 found that the most popular soups[128] in England were tomato, leek and potato, chicken, carrot and coriander, mushroom, pea and ham[129] (sometimes known as London Particular), and broccoli and stilton.[130] Other traditional soups[131] include vegetable, oxtail, cauliflower, artichoke, asparagus, spinach, parsnip, chestnut, watercress and chilled cucumber. Broth[132] consists of meat and vegetables cooked in stock, sometimes thickened with barley or other cereals.[133] Brown Windsor soup appeared in the 1953 Ealing film comedy The Captain's Paradise and, although opinion is divided as to whether and for how long it actually existed in real life,[134] recipes for it can now be found. Worcestershire sauce[135] and brown sauce, along with ketchup, are distinctive English condiments.[136] Bovril and Marmite are food pastes with a distinctive flavour.

Desserts and puddings

English desserts include (Bramley) apple pie, cherry pie, bread and butter pudding, bread pudding, fruit crumble, fruit cobbler, Eve's pudding, Dorset apple cake, baked apple, gooseberry fool, sticky toffee pudding, treacle tart, treacle sponge pudding (made with golden syrup),[137] jam roly-poly, spotted dick, Bakewell tart, trifle, rice pudding, Eton mess, cheesecake/curd tart,[138] Sussex pond pudding, summer pudding, Cabinet pudding, English custard tart and, since the 1970s, lemon meringue pie and banoffee pie.[139] Hot puddings are often served with custard.[140] Some puddings, such as jelly, blancmange and chocolate sponge with chocolate custard, are associated with school dinners. Fruit salad is a mixture of fresh fruit and canned fruits such as peaches and apricots served in syrup. Fruits grown in England include apples, pears, plums, cherries, damsons, blackberries, black currants, gooseberries, raspberries, strawberries (often served with cream) and rhubarb.[141] Ice creams are sometimes sold from ice cream vans which use distinctive chimes to attract customers[142]

Full English breakfast

The full English breakfast,[143] also referred to as 'bacon and eggs' or a 'fry up', typically comprises a choice from rashers of back bacon,[144] fried or scrambled eggs, pork sausages, black pudding, grilled tomatoes, mushrooms, baked beans, fried bread, hash browns (which largely displaced bubble and squeak[145] in the 1970s), and sometimes white pudding;[146] usually served with toast and jam, marmalade or honey,[147] and a cup of coffee or tea[148] Alternative breakfast dishes include boiled eggs[149] with toast soldiers, smoked salmon and scrambled eggs, poached eggs on toast, and Craster kippers.[150]

Despite Johnson's definition of the word 'oats' as "a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people",[151] porridge has long been eaten[152] in England as a breakfast cereal. Fruit juice and yogurt are more recent additions.

Afternoon tea

Traditionally, High Tea would be had as a full evening meal, whereas Afternoon Tea was a lighter meal taken earlier in the afternoon only by the upper and middle classes of society, the idea being popularized by Anna Russell, Duchess of Bedford in the 1840s. A cream tea includes a pot of tea and scones (or buns called splits) served with jam and clotted cream from Devon or Cornwall,[153] sometimes accompanied by dainty finger sandwiches, with fillings such as cucumber and smoked salmon,[154] cake, small pastries and fruit tarts.[155] Teas are typically served in tearooms and hotels.

English cakes include a variety of fruit cakes,[156] such as Genoa cake, and sponge cakes, such as Victoria sponge,[157] Madeira cake, Battenberg cake, chocolate sponge, coffee cake, lemon drizzle cake, fairy cakes and Queen cakes. Wartime rationing popularised carrot cake.[158] Simnel cake is a special fruit cake associated with Mothering Sunday and Easter.[159] The traditional wedding cake is made from a rich fruitcake. Parkin and toffee apples are eaten on Guy Fawkes Night. Particular types of gingerbread are associated with Grasmere, Market Drayton and Cornwall. Eccles cakes and Banbury cakes are small round cakes filled with currants. Other items served for afternoon tea[160] include teacakes, crumpets and pikelets,[161] English muffins,[162] Cornish saffron cake and buns, tea loaf, malt loaf, seed cake, rock cakes, flapjacks, jam tarts, maids of honour tarts, doughnuts and lardy cakes.[163] Lemon curd or honey[164] may be served at afternoon tea as an alternative to jam. Cheese scones are made using grated cheese with a strong flavour such as Cheddar or Red Leicester.

There are several types of fruited bun such as currant buns, Chelsea buns, Bath buns and hot cross buns (the latter marking Good Friday).[165] English Pancakes are served on Shrove Tuesday.[166]

Types of English loaves,[167] generally leavened bread made using white and/or wholemeal bread flour milled from hard wheat, include farmhouse,[168] cottage,[169] bloomer[170] cob,[171] Coburg,[172] crusty,[173] plait,[174] tin,[175] and sandwich.[176] Since the 1960s much commercially produced bread has used the Chorleywood bread process, but from the 1990s there has been growing interest in artisanal and home baking[177] as well as sourdough bread.[178] Bread rolls are most commonly round in shape and may be crusty or soft.[179]

Cheese and other dairy products

Consumption of dairy products in England has varied over time. Historically farms turned surplus milk into cheese and households made simple cream cheese and cottage cheese.[180] The coming of the railways meant fresh milk could be transported quickly to the cities.[181] Until the 1990s milk was generally delivered to customers in reusable glass milk bottles to the door by a milkman driving an electric milk float, but by 2018 supermarket sales of different kinds of milk in plastic cartons and of cream accounted for over 95% of the market.[182] Yellow sweetcream (rather than lactic)[183] butter is most common in England, in both salted and unsalted varieties.[184] Commercial standardisation in the late 19th century[185] led to a fairly limited number of regional (generally hard) cheeses, including:

- Cheddar cheese[186]

- Cheshire cheese

- Blue and White Stilton cheese[187]

- Wensleydale cheese

- Lancashire cheese

- Double Gloucester cheese[188]

- Red Leicester cheese

- Shropshire Blue cheese

- Dorset Blue Vinney cheese

- Swaledale cheese

- Sage Derby cheese

English cheesemaking was restricted by wartime rationing and the number of dairy farms has diminished considerably since the abolition of the Milk Marketing Board in 1994,[189] but many of the remaining producers sell added-value products such as artisanal cheese and farmhouse ice cream[190] and there are now over 750 different cheeses.[191] Recent decades have seen English replicas of French cheeses, such as Brie,[192] Camembert[193] and chèvre.[194] A number of British cheeses were accepted as having EU protected geographical status. Homegrown artisanal cheeses are made by both long-established and new producers. These include hard cheeses such as Lincolnshire Poacher, and semi-soft or soft cheeses, such as Stinking Bishop, Cornish Yarg and Oxford Blue.

Drinks

Tea and beer are typical and rather iconic drinks in England. Beer is used metaphorically to refer to pleasure, as in cakes and ale and beer and skittles. Most tea drunk in England is black tea.[195] The types of single origin tea most commonly sold are Assam and Darjeeling from India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Lapsang Souchong from China.[196] English breakfast tea is a strong blend that goes well with milk and sugar. Earl Grey tea is flavoured with bergamot. A cup of tea is often accompanied with a biscuit or piece of cake.

Whilst tea drinking and tearooms have diminished since the rise of instant coffee consumption in the 1970s[197] and global chains of coffee shops in the 1990s,[198] there has been a rapid growth in the number of breweries since the early 1970s.[199] This was driven initially by a renewed interest in cask ale, stimulated by the Campaign for Real Ale and its Good Beer Guide, and more recently by the global influence of, particularly American, craft brewing.[200]

Traditional English beer,[201] unlike lager, is made with warm/top-fermenting yeasts and encompasses bitter and pale ale, other (less hoppy) types of ale, porter[202] and stout.[203] Pale ale, when served draught, gained the name of bitter amongst drinkers in the first half of the 19th century because it was more hopped than other ales of the time such as mild, but is generally much less hopped than modern American pale ale.[204] India pale ale was exported to India but also consumed in England.[205] Pale ale has long been sold in bottled form and Burton Pale Ale enjoyed particular popularity.[206] Light ale is a low-alcohol bitter, often bottled.[207] More recently the terms golden ale[208] and amber ale[209] have been used to differentiate between pale ales of different shades. Other types of ale include strong Burton Ale,[210] old ale,[211] barley wine,[212] mild ale,[213] and brown ale.[214] Bitter became the predominant English beer style in the 1950s, largely supplanting mild ale and Burton ale,[215] and has accordingly been described as "the national drink of England".[216] Research in 2014 found that although "beer fans divide equally between ale and lager drinkers … classic bitter is still the favourite for ale drinkers".[217] Cobra Beer is an Indian-style lager that was created in 1989 to be drunk with food, which is now brewed in Burton upon Trent and sold in almost all Indian restaurants. Cider and perry is produced in the West Country.[218] Scrumpy refers to rough dry farmhouse cider. Shandy is beer mixed with a non-alcoholic drink, such as lemonade.[219] Ginger beer is a usually sold as a non-alcoholic, carbonated drink flavoured with ginger, but is sometimes brewed (fermented).[220]

Magna Carta stated there should be a single measure for ale.[221] In pubs beer and cider are served draught by the pint or half-pint, either in a straight glass or a dimpled glass tankard (known as a jug),[222] and may be drunk with snack food (e.g. crisps, dry roasted or salted peanuts, and pork scratchings) or a meal[223] However, the number of pubs fell by around a third between the early 1970s and 2017[224] and since 2014 more beer has been sold in bottles by supermarkets and off licences (off-trade) than in pubs (on-trade).[225] Marston's Brewery and Greene King are the two largest brewers of premium cask and bottled beers, having grown by acquisition. Shepherd Neame Brewery is the largest family-owned brewery.

Gin has been popular in England since the late 17th century and is mixed with tonic water, ice and a slice of lemon.[226] Pimm's No. 1 Cup, a gin-based drink containing a mixture of herbs and liquors, is used to make punch for summer social events.[227] The rise of micro-distilleries in England at the start of the 21st century led to an upsurge in interest in both gin and vodka. The south of England has seen the reintroduction of vineyards making English wine.[228] Lemon barley water, invented by Matthias Archibald Robinson in 1823,[229] is made by pouring pearl barley water over the rind and/or pulp of a lemon and adding sugar to taste. The Wimbledon tennis championships are associated with this drink.

Folklore

English folklore developed over many centuries. Some of the characters and stories are present all over England, but most belong to specific regions. Common folkloric beings include pixies, giants, elves, trolls, goblins and dwarves. While many legends and folk-customs are thought to be ancient, for instance the tales featuring Offa of Angel and Wayland the Smith,[230] others date from after the Norman conquest of England: Robin Hood and his Merry Men of Sherwood and their battles with the Sheriff of Nottingham are perhaps the best known.[231]

During the High Middle Ages tales originated from Brythonic traditions, notably the Arthurian legend.[232][233] Deriving from Welsh sources; King Arthur, Excalibur and Merlin, while the Jersey poet Wace introduced the Knights of the Round Table. These stories are most centrally brought together within Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae. Another early figure from British tradition, King Cole, may have been based on a real figure from Sub-Roman Britain. Many of the tales and pseudo-histories make up part of the wider Matter of Britain, a collection of shared British folklore.

Some folk figures are based on semi-historical or historical people whose stories have been passed down the centuries; Lady Godiva for instance was said to have ridden naked on horseback through Coventry, Hereward the Wake was a heroic English figure resisting the Norman invasion, Herne the Hunter is an equestrian ghost associated with Windsor Forest and Great Park (whose tale bears the common European folkloric motif of the Wild Hunt) and Mother Shipton is the archetypal witch.[234] The chivalrous bandit, such as Dick Turpin, is a recurring character. There are various still surviving national and regional folk activities, such as Morris dancing, Maypole dancing, Rapper sword in the North East, Long Sword dance in Yorkshire, Mummers Plays, bottle-kicking in Leicestershire, and cheese-rolling at Cooper's Hill.[235] There is no official national costume, but a few costumes are well established, such as the Pearly Kings and Queens associated with cockneys, the Royal Guard, the Morris costume and Beefeaters.[236] The utopian vision of a traditional England is sometimes referred to as Merry England.

Published in 1724, A General History of the Pyrates by Captain Charles Johnson provided the standard account of the lives of many pirates in the Golden Age of Piracy.[237] Many famous English pirates from the Golden Age hailed from the West Country in the south west coast of England—the stereotypical West Country "pirate accent" was popularised by West Country native Robert Newton's portrayal of Long John Silver in film.[238][239] The concept of "walking the plank" was popularised by J. M. Barrie's novel, Peter Pan, where Captain Hook's pirates helped define the archetype.[240] Davy Jones' Locker where sailors or ship's remains are consigned to the bottom of the sea is first recorded by Daniel Defoe in 1726.[241] Johnson's 1724 book gave a mythical status to famous English pirates such as Blackbeard and Calico Jack. Jack is known for his Jolly Roger flag design, a skull with crossed swords.[242]

The Gremlin is part of Royal Air force folklore dating from the 1920s, with gremlin being RAF slang for a mischievous creature that sabotages aircraft, meddling in the plane's equipment.[243] Legendary figures from 19th century London whose tales have been romanticised include Sweeney Todd, the murderous barber of Fleet Street, and serial killer Jack the Ripper. On 5 November, people in England make bonfires, set off fireworks and eat toffee apples in commemoration of the foiling of Guy Fawkes' Gunpowder Plot, which became an annual event after The Thanksgiving Act of 1606 was passed.[244] Guy Fawkes mask is an emblem for anti-establishment protest groups.[245]

The English language

English people traditionally speak the English language, a member of the West Germanic language family. The modern English language evolved from Middle English (the form of language in use by the English people from the 12th to the 15th century); Middle English was influenced lexically by Norman-French, Old French and Latin. In the Middle English period Latin was the language of administration and the nobility spoke Norman French. Middle English was itself derived from the Old English of the Anglo-Saxon period; in the Northern and Eastern parts of England the language of Danish settlers had influenced the language, a fact still evident in Northern English dialects.

There were once many different dialects of modern English in England, which were recorded in projects such as the English Dialect Dictionary (late 19th century) and the Survey of English Dialects (mid 20th century), but many of these have passed out of common usage as Standard English has become more widespread through education, the media and socio-economic pressures.[246]

Cornish, a Celtic language, is one of three existing Brythonic languages; its usage has been revived in Cornwall. Historically, another Brythonic Celtic language, Cumbric, was spoken in Cumbria in North West England, but it died out in the 11th century although traces of it can still be found in the Cumbrian dialect. Early Modern English began in the late 15th century with the introduction of the printing press to London and the Great Vowel Shift. Through the worldwide influence of the British Empire, English spread around the world from the 17th to mid-20th centuries. Through newspapers, books, the telegraph, the telephone, phonograph records, radio, satellite television, broadcasters (such as the BBC) and the Internet, as well as the emergence of the United States as a global superpower, Modern English has become the international language of business, science, communication, sports, aviation, and diplomacy.

In schools, language teaching is compulsory from the age of seven. French, German, and Spanish are commonly taught in all schools. Arabic, Bengali, Mandarin, Greek, Gujarati, Modern Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Panjabi, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Turkish, Urdu are also taught.[247]

Surnames

| Rank | Surname | Origin | Percentage[248] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smith | England and Scotland | 1.44 |

| 2 | Jones | Wales | 0.75 |

| 3 | Taylor | England | 0.59 |

| 4 | Brown | England and Scotland | 0.56 |

| 5 | Williams | England and Wales | 0.39 |

| 6 | Wilson | England and Scotland | 0.39 |

| 7 | Johnson | England and Scotland | 0.37 |

| 8 | Davis | Wales | 0.34 |

| 9 | Robinson | England | 0.32 |

| 10 | Wright | England | 0.32 |

| 11 | Thompson | England and Scotland | 0.31 |

| 12 | Evans | Wales | 0.30 |

| 13 | Walker | England | 0.30 |

| 14 | White | England | 0.30 |

| 15 | Roberts | England and Wales | 0.28 |

| 16 | Green | England | 0.28 |

| 17 | Hall | England | 0.28 |

| 18 | Woods | England and Scotland | 0.27 |

| 19 | Jackson | England, Scotland and Ireland | 0.27 |

| 20 | Clarke | England and Ireland | 0.26 |

Education

English school children begin compulsory education at the age of 5-6. Foundation stage is for those under the age of 5. Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2 are primary levels, and compulsory National Curriculum subjects include: English, mathematics, science, history, geography, art & design, design & technology, ancient & modern languages, computing, music, religious education, and physical education.[249]

Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4 are secondary levels, and compulsory National Curriculum subjects include: English literature, English language, mathematics, science (biology, chemistry, physics, astronomy, etc), citizenship, history, geography, art & design, design & technology, modern languages, computing, music, religious education, and physical education.[250] Photography, drama & media arts, business studies & economics, psychology, sociology, philosophy, dance, film studies, media studies, graphics, food preparation & nutrition, electronics, engineering and other subjects are also taught.

In the final years of compulsory secondary education at Key Stage 4, English school students typically select an optional programme of study based on learning interests or career prospects from the Sciences and Mathematics, Humanities and Social Sciences, Business and Enterprise, Arts and Design, Design and Technology, and Ancient and Modern Languages.[250]

At the end of Key Stage 4, English school students sit very intense examinations known as GCSEs. In Key Stage 5, English students prepare for a more intense and challenging examinations known as A-Levels to pursue higher education. Some English students study an apprenticeship to learn skilled trades and pursue T-Levels to progress towards skilled employment, further study or a higher apprenticeship.

English school students wear school uniforms; school uniforms are defined by individual schools, within the constraint that uniform regulations must not discriminate on the grounds of sex, race, disability, sexual orientation, gender reassignment, religion or belief. Schools may choose to permit trousers for girls or religious dress.[251]

The Programme for International Student Assessment coordinated by the OECD currently ranks the overall knowledge and skills of British 15-year-olds as 13th in the world in reading literacy, mathematics, and science with the average British student scoring 503.7, compared with the OECD average of 493, ahead of the United States, and most of Europe.[252]

British higher education emanates from the alumni of its world renowned institutions. Prominent people that have reached the apex in their respective fields have been products of British higher education. Britain is home to some of the world's most prominent institutions of higher learning and ranked among the top universities in the world. Institutions such as the University of Cambridge, the University of Oxford, Imperial College London, and UCL consistently rank among the world's top ten universities.[253]

The law

English law is the legal system of England and Wales.[254] Due to the British Empire, it has been exported across the world: it is the basis of common law jurisprudence.[255] The 18th century English jurist, judge and politician Sir William Blackstone is best known for his seminal work, Commentaries on the Laws of England, containing his formulation: "It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer", a principle that government and the courts must err on the side of innocence, which has remained constant.[256] Sir William Garrow ushered in the adversarial court system in common law. He coined the phrase "presumed innocent until proven guilty", insisting that defendants' accusers and their evidence be thoroughly tested in court.[257]

Major constitutional documents include: Magna Carta (foundation of the "great writ" Habeas corpus—safeguarding individual freedom against arbitrary state action), the Bill of Rights 1689 (one provision granting freedom of speech in Parliament), Petition of Right, Habeas Corpus Act 1679 and Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949. The jurist Albert Venn Dicey wrote that the British Habeas Corpus Acts "declare no principle and define no rights, but they are for practical purposes worth a hundred constitutional articles guaranteeing individual liberty".[258] A strong advocate of the "unwritten constitution", Dicey stated English rights were embedded in English common law, and "the institutions and manners of the nation".[259]

Charitable organizations

England and the rest of the United Kingdom has a strong civil society. Children in Need and Comic Relief are popular charitable events broadcast by the BBC yearly drawing in millions of pounds for charity from viewers. Charitable organizations for healthcare, nature, wildlife, animals, society, heritage, education, etc are widespread. The British Heart Foundation, St. John Ambulance, British Red Cross, Dogs Trust, Arts Council England, Duke of Edinburgh Awards, and the Prince's Trust are some notable charities.

Religion

Christianity became the dominant religion in England in the 7th century. Polytheistic Indo-European religions, often referred to as paganism, were practised before Christianity took hold. The most notable of these religions were Celtic polytheism, Roman polytheism and Anglo-Saxon paganism, which was the religion of the early English people, or Anglo-Saxons, and which was in many ways very similar to the closely related Norse paganism practised by the Scandinavian peoples and that would later be introduced to England by the Danes.

Christianity was first established in Britain by the Roman Empire. According to legend, Christianity was introduced to Britain by Joseph of Arimathea, who came to Glastonbury. There is also a tradition ascribing this accomplishment to Lucius of Britain. Archaeological evidence for Christian communities begins to appear in the 3rd and 4th centuries. The Romano-British population after the withdrawal of the Roman legions remained mostly Christian. The Anglo-Saxon invaders and settlers who replaced them, founding the English nation, represented a stark return to pre-Christian religion for Britain. From the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons beginning in the 4th century until the arrival of the Augustinian Mission in 597 AD, England was entirely pagan, and the pre-Christian Germanic religion was practised openly in pockets throughout the country for many decades after this.

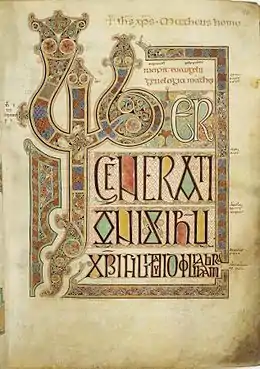

Christianity was reintroduced into England by missionaries from Scotland and from Continental Europe: the era of Augustine of Canterbury, the first Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Celtic Christian missionaries in the north (notably Aidan of Lindisfarne and Cuthbert who came from Scotland) began in 597 AD. The Synod of Whitby in 664 ultimately led to the Church of England being fully part of the Catholic Church. Early English Christian documents from this time include the 7th-century illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels and the historical accounts written by Bede. The Durham Gospels is a Gospel book produced at Lindisfarne.

In 1536, the Church of England split from Rome over the issue of the divorce (technically, the marriage annulment) of King Henry VIII from Catherine of Aragon. The split led to the emergence of a separate ecclesiastical authority. Later the influence of the Reformation resulted in the Church of England adopting its distinctive reformed Catholic position known as Anglicanism which maintains episcopacy while adopting a Lutheran theology. For more detail of this period see the following article: Timeline of the English Reformation.

Today, the Church of England is the established church in England. It regards itself as in continuity with the pre-Reformation state Catholic church (something the Roman Catholic Church does not accept) and has been a distinct Anglican church since the settlement under Elizabeth I of England (with some disruption during the 17th-century Commonwealth of England period). The British Monarch is formally Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Its spiritual leader is the Archbishop of Canterbury, who is regarded by convention as the head of the worldwide Anglican Communion. In practice the Church of England is governed by the General Synod of the Church of England, under the authority of Parliament. The Church of England's mission to spread the Gospel has seen the establishment of many churches in the Anglican Communion throughout the world particularly in the Commonwealth of Nations.

A strong tradition of Methodism developed from the 18th century onward. The Methodist revival was started in England by a group of men including John Wesley and his younger brother Charles Wesley as a movement within the Church of England; it developed as a separate denomination after John Wesley's death. Other non-conformist Protestant traditions were also established in England. Saint George is recognised as the patron saint of England. Before Edward III, Edmund the Martyr was recognised as England's patron saint, and the flag of England consists of the Saint George's Cross. However, Saint Alban is venerated by some as England's first Christian martyr.

Change ringing is the traditional method of bell ringing in English churches, co-ordinated by the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers[260] and promoted by societies such as the Ancient Society of College Youths and the Society of Royal Cumberland Youths. Change ringing is central to The Nine Tailors by Dorothy L. Sayers, voted the best crime novel of the 1930s by the British Crime Writers' Association.[261]

Celebration of Christmas

In 17th-century England, the Puritans condemned the celebration of Christmas.[262] In contrast, the Anglican Church "pressed for a more elaborate observance of feasts, penitential seasons, and saints' days. The calendar reform became a major point of tension between the Anglicans and Puritans."[263] The Catholic Church also responded, promoting the festival in a more religiously oriented form. King Charles I of England directed his noblemen and gentry to return to their landed estates in midwinter to keep up their old-style Christmas generosity. Following the Parliamentarian victory over Charles I during the English Civil War, Puritan rulers banned Christmas in 1647.[264]

Protests followed as pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities and for weeks Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalist slogans.[262] The book, The Vindication of Christmas (London, 1652), argued against the Puritans, and makes note of Old English Christmas traditions, dinner, roast apples on the fire, card playing, dances with "plow-boys" and "maidservants", old Father Christmas and carol singing.[265] The Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 ended the ban. Following the Restoration, Poor Robin's Almanack contained the lines: "Now thanks to God for Charles return, / Whose absence made old Christmas mourn. / For then we scarcely did it know, / Whether it Christmas were or no."[266]

In the early 19th century, writers imagined Tudor Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration. In 1843, Charles Dickens wrote the novel A Christmas Carol that helped revive the "spirit" of Christmas and seasonal merriment.[267][268] Dickens sought to construct Christmas as a family-centred festival of generosity, in contrast to the community-based and church-centred observations, the observance of which had dwindled during the late 18th century and early 19th century.[269] Dickens influenced many aspects of Christmas that are celebrated today in Western culture, such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games, and a festive generosity of spirit.[270] A prominent phrase from the tale, "Merry Christmas", was popularized following the appearance of the story.[271] The term Scrooge became a synonym for miser, with "Bah! Humbug!" dismissive of the festive spirit.[268]

The revival of the Christmas Carol began with William Sandys's Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (1833), with the first appearance in print of "The First Noel", "I Saw Three Ships", "Hark the Herald Angels Sing" and "God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen". In 1843 the first commercial Christmas card was produced by Henry Cole leading to the exchange of festive greeting cards among the public.[272]

Science

England has been a leading centre of the Scientific Revolution since the 17th century.[273] The English have played a significant role in the development of science and engineering. Prominent individuals have included Roger Bacon, Francis Bacon, William Harvey, Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton, Edward Jenner, Henry Cavendish, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Francis Crick, Charles Babbage, Abraham Darby, Michael Faraday, Charles Darwin, James Chadwick, Joseph Swan, Barnes Wallis, Alan Turing, Frank Whittle, Tim Berners-Lee and Stephen Hawking. It is home to the Royal Institution, the Royal Society, the Greenwich Observatory and its associated meridian.

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began in England due to the social, economic and political changes implemented in the previous centuries. Whereas absolute monarchy stayed the normal form of power execution through most parts of Europe, institutions ensured property rights and political safety to British people after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Aided by these legal and cultural foundations, an entrepreneurial spirit and consumer revolution drove industrialisation in Britain.[274] Geographical and natural resource advantages of Great Britain also contributed, with the country's extensive coastlines and many navigable rivers in an age when water was the easiest means of transportation. Britain also had high quality coal. According to British historian Jeremy Black, "an unprecedented explosion of new ideas, and new technological inventions, transformed our use of energy, creating an increasingly industrial and urbanised country. Roads, railways and canals were built. Great cities appeared. Scores of factories and mills sprang up. Our landscape would never be the same again. It was a revolution that transformed not only the country, but the world itself."[275]

The 18th century entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood is credited with the industrialisation of the manufacture of pottery. Meeting the demands of the consumer revolution and growth in wealth of the middle classes in Britain, Wedgwood created goods such as tableware, which was starting to become a common feature on dining tables.[275] Credited as the inventor of modern marketing, Wedgwood pioneered direct mail, money back guarantees, travelling salesmen, carrying pattern boxes for display, self-service, free delivery, buy one get one free, and illustrated catalogues.[276] Described as "natural capitalists" by the BBC, dynasties of Quakers were successful in business and contributed the Industrial Revolution. This included ironmaking by Abraham Darby I and his family; banking, including Lloyds Banking Group (founded by Sampson Lloyd),[277] Barclays PLC,[277] Backhouse's Bank and Gurney's Bank; life assurance (Friends Provident); pharmaceuticals (Allen & Hanburys[277]); the big three British chocolate companies, Cadbury,[277] Fry's[277] and Rowntree[277]); biscuit manufacturing (Huntley & Palmers[277]); match manufacture (Bryant and May) and shoe manufacturing (Clarks). With his role in the marketing and manufacturing of James Watt's steam engine, and invention of modern coinage, Matthew Boulton is regarded as one of the most influential entrepreneurs in history.[278]

Other important English engineers and inventors in the Industrial Revolution include: George Stephenson, Richard Arkwright, Henry Maudslay and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. England has the oldest railway networks in the world; the Stockton and Darlington Railway, opened in 1825, was the first public railway to use steam locomotives.[279] Opened in 1863, London Underground is the world's first underground railway.[280] Known as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson's rail gauge of 4 feet 8 1⁄2 inches (1,435 mm) is the standard gauge for most of the world's railways. Henry Maudsley's most influential invention was the screw-cutting lathe, a machine which created uniformity in screws and allowed for the application of interchangeable parts (a prerequisite for mass production): it was a revolutionary development necessary for the Industrial Revolution.[281][282] Brunel created the Great Western Railway, as well as famous steamships including the SS Great Britain, the first propeller-driven ocean-going iron ship, and SS Great Eastern which laid the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable.[283]

Philosophy

England has been the cradle of many very important philosophers who have contributed to the development of philosophical currents such as liberalism, utilitarianism, free thinking, enlightened thinking, empiricism, political philosophy and analytical philosophy. The ideas of these thinkers have influenced transcendental historical events such as the Age of Enlightenment, the 1776 Declaration of Independence of the United States. the French Revolution, and the 1948 United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- Thomas More (1478-1535) addressed the social problems of humanity in his summit work, Utopia (1516). The rest of his works have as a common thread the exaltation of idealism and the condemnation of tyranny.

- Francis Bacon (1561-1626) developed philosophical and scientific empiricism, which made him one of the pioneers of modern scientific thinking in developing the experimental scientific method. His most prominent philosophical works are The Advancement of Knowledge (1605), Novum Organum or Indications related to the interpretation of nature (1620).

- Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was a very influential figure in the development of Western political philosophy through his work Leviathan (1651), a treatise on the nature of human beings and how societies are organized.

- John Locke (1632-1704) is considered the father of enlightened thought, one of the most influential thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment, and one of the founders of social contract theory, epistemology and political philosophy .

- Thomas Paine (1737-1809) had great influence through his writings on social democracy, claiming land ownership, freethinking, religion and slavery, in the American revolutionaries who led the independence of that country.

- Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) developed the utilitarian doctrine, embodied in his main work: Introduction to the principles of morality and legislation (1789). In addition, it left strengthened and appropriate the concept of Deontology widely used in laws and codes of professional work that looks to the future.

- John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was a representative of the classical and theoretical economic school of utilitarianism. In his work on freedom, he exposes his fundamental ideas about the limits of freedom of the individual and society.

- Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) was a philosopher, mathematician, logician and writer, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, and known for his influence on analytical philosophy in the early twentieth century.

Sport

There are many sports which have been codified by the English, and then spread worldwide, including badminton, cricket, croquet, football, field hockey, lawn tennis, rugby league, rugby union, table tennis and thoroughbred horse racing. In the late 18th century, the English game of rounders was transported to the American Colonies, where it evolved into baseball. Association football, cricket, rugby union and rugby league are considered to be the national sports of England.