Sitakunda Upazila

Sitakunda (Bengali: সীতাকুণ্ড Shitakunḍo, IPA: [ʂitakunɖo]) is an upazila, or administrative unit, in the Chittagong District of Bangladesh. It includes one urban settlement, the Sitakunda Town, and 10 unions, the lowest of administrative units in Bangladesh. It is one of the 15 upazilas, the second tier of administrative units, of the Chittagong District, which also includes 33 thanas, the urban equivalent of upazilas. The district is part of the Chittagong Division, the highest order of administrative units in Bangladesh. Sitakunda is the home of the country's first eco-park, as well as alternative energy projects, specifically wind energy and geothermal power.

Sitakunda

সীতাকুণ্ড | |

|---|---|

| |

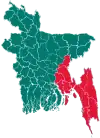

Sitakunda Location in Bangladesh | |

| Coordinates: 22°37′N 91°39.7′E | |

| Country | Bangladesh |

| Division | Chittagong Division |

| District | Chittagong District |

| Headquarters | Sitakunda |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,893.97 km2 (1,889.57 sq mi) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 335,178 |

| • Density | 68/km2 (180/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| Postal code | 4310 |

| Website | Sitakund |

Sitakunda is one of the oldest sites of human habitation in Bangladesh. During much of its history, it was ruled alternatively by various Buddhist rulers of Myanmar in the east and Muslims rulers of Bengal in the west. For a brief period in the 8th century, it was ruled by the Buddhist Pala Empire of India. The eastern rulers originated from the Kingdom of Arakan, the Mrauk U dynasty, Arakanese pirates and the Pagan Kingdom. The western rulers came from the Sultanate of Bengal and the Mughal province (Suba) of Bangala. European rule of Sitakunda was heralded by Portuguese privateers in 16th and 17th centuries, who ruled together with the pirates; and the British Raj in 18th and 19th centuries, who unified Sitakunda into the rest of the Chittagong District. Diderul Alam is the Current Member of parliament of Sitakunda

Economic development in Sitakunda is largely driven by the Dhaka-Chittagong Highway and the railway. Though Sitakunda is predominantly an agricultural area, it also has the largest ship breaking industry in the world.[1][2] The industry has been accused of neglecting workers' rights, especially concerning work safety practices and child labor. It has also been accused of harming the environment, particularly by causing soil contamination. Sitakunda's ecosystems are further threatened by deforestation, over-fishing, and groundwater contamination. The upazila is also susceptible to natural hazards such as earthquakes, cyclones, and storm surges. It lies on one of the most active seismic faults in Bangladesh, the Sitakunda–Teknaf fault.

Sitakunda is renowned for its numerous Islamic, Hindu and Buddhist shrines. It has 280 mosques, 8 mazars, 49 Hindu temples, 4 ashrams, and 3 Buddhist temples. Among its notable religious sites are the Chandranath Temple (a Shakti Peetha or holy pilgrimage site), Vidarshanaram Vihara (founded by the scholar Prajnalok Mahasthavir), and the Hammadyar Mosque (founded by Sultan Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah). The attraction of Sitakunda as a tourist destination is elevated by these pilgrimage sites along with the hill range and the eco-park. Despite its diverse population, the area has gone through episodes of communal strife, including attacks on places of worship. There have been reports of activity by the Islamic militant group Jama'atul Mujahideen Bangladesh since the early 2000s.[3][4]

History

.jpg.webp)

The legends of the area state the sage Bhargava created a pond (kunda) for Sita to bathe in when her husband Lord Ramchandra visited during his exile in the forests. Sitakunda derived its name from this incident.[5][6]

Sitakunda has been occupied by humans since the Neolithic era; tools associated with the prehistoric Assam group have been found throughout the area.[7] In 1886, shouldered celts manufactured from petrified wood were discovered, as reported by Indian archaeologist Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay in his book Banglar Itihas, or History of Bengal, (volume I, 1914).[8][9] In 1917, British mineralogist Dr. J. Coggin Brown uncovered more prehistoric celts.[10] Large quantities of pebbles have also been found, but archaeologists have not determined whether they were used in the construction of prehistoric tools.[8]

During the 6th and 7th centuries CE, the Chittagong region was ruled by the Kingdom of Arakan.[11] In the next century, it was briefly ruled by Dharmapala (reign: 770–810) of the Pala Empire.[12] The area was conquered in 1340 by Sultan Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah (reign: 1338–1349) of Sonargaon, who founded the first dynasty of the Sultanate of Bengal.[11] When Sultan Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah (reign: 1533–1538) of the last dynasty of the Sultanate of Bengal was defeated in 1538 by Sher Shah Suri of the Sur Dynasty, the Arakanese captured the region again. Batsauphyu (reign: 1459–1482) of the Mrauk U dynasty took advantage of the weakness of Sultan Barbak Shah of Bengal to lead the invasion.[13] In this period, Keyakchu (or Chandrajyoti), a prince of Arakan, established a monastery in Sitakunda.[14] Between 1538 and 1666, Portuguese privateers (known as Firinghis or Harmads) made inroads into Chittagong and ruled the region in alliance with Arakanese pirates. During those 128 years, the eastern coast of Bengal became a home to pirates of Portuguese and Arakanese origins.[13][15][16] For a brief period in 1550, it was taken over by Pagan invaders.[17] In 1666, Mughal commander Bujurg Umed Khan conquered the area.[11][13]

Along with the rest of Bengal, Sitakunda came under the rule of the British East India Company after the company's defeat of the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Rapid growth in the Bengali population since then resulted in an exodus of non-Bengali people from Sitakunda and its vicinity to the Chittagong Hill Tracts.[18][19] During the Ardhodaya Yog movement, a part of the Swadeshi Indian independence movement, the governance of Sitakunda was briefly in the hands of Indian nationalists when, in February 1908, they took over the central government in Kolkata.[20][21] In 1910, Indian Petroleum Prospecting Company drilled here for hydrocarbon exploration, the first such activity in East Bengal. In 1914, the first onshore wildcat well in Bangladesh was drilled at Sitakunda anticline to a depth of 762 metres (2,500 ft).[22] By 1914, however, all four of the wells drilled had proven to be failures.[23]

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British colonial government (British Raj) replaced the governance of the East India Company. When the British withdrew in 1947, after creating the independent states of India and Pakistan, Sitakunda became a part of East Pakistan. The potential for a ship breaking industry first appeared in 1964 when Chittagong Steel House started scrapping MD Alpince, a 20,000 metric tons (19,684 long tons) Greek ship that had been accidentally beached near Fouzdarhat by a tidal bore four years earlier.[24][25][26] On 15 February 1950, Hindu pilgrims form all over East Bengal, Tripura and Assam arriving for Maha Shivaratri were attacked by the Ansars and armed Muslim mobs and massacred at the Sitakunda railway station.[27][28]

During the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, Sitakunda was part of Sector 1, led by Ziaur Rahman and Major Rafiqul Islam of the Mukti Bahini, the forces fighting for the independence of Bangladesh. The ship breaking industry began in earnest in 1974 when Karnafully Metal Works started scrapping Al Abbas, a Pakistani ship damaged in 1971, and flourished in the 1980s.[24][29] As of 2007, Sitakunda had overtaken the ship breaking industries of India and Pakistan to become the largest in the world.[1][2]

In the early 2000s, Islamic militant organization Jama'atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) leader Siddikul Islam (also known as Bangla Bhai) ran militant training centers in the upazila at which participants learned to make bombs and handle firearms.[4][30] One of his followers, Mahfuzul Huq, was captured on 21 February 2006.[3]

Geography and climate

.jpg.webp)

Sitakunda Upazila occupies an area of 483.97 square kilometres (186.86 sq mi),[31] which includes 61.61 square kilometres (23.79 sq mi) of forest.[32] It is bordered by Mirsharai to the north, Pahartali to the south, Fatickchhari, Hathazari and Panchlaish to the east, and the Sandwip Channel in the Bay of Bengal to the west.[33] The Sitakunda range is a 32-kilometre (20 mi) long ridge in the center of the upazila, which reaches an altitude of 352 metres (1,155 ft) above sea level at Chandranath or Sitakunda peak, the highest peak in Chittagong District.[16][34] Part of Sitakunda is covered by the low hill ranges, while the rest is in the Bengal flood plain.[34] To the north, Rajbari Tila at 274 metres (899 ft) and Sajidhala at 244 metres (801 ft) are the highest peaks in this range, which drops abruptly to a height of less than 92 metres (302 ft) in the vicinity of Chittagong City to the south.[34] About 5 kilometres (3 mi) north of Sitakunda Town is the Labanakhya saltwater hot spring, which has been proposed as a source of geothermal energy.[35][36] There are two waterfalls in the hills: Sahasradhara (thousand streams) and Suptadhara (hidden stream).[37] Both have been identified as sites requiring special attention for protection and preservation by the National Heritage Foundation of Bangladesh.[38]

An area prone to cyclones and storm surges,[39] Sitakunda was affected by cyclones in 1960, 1963, 1970, 1988, 1991, 1994 and 1997; the cyclones of 29 May 1963, 12 November 1970, 29 April 1991 made landfall.[40] The intra-deltaic coastline is very close to the tectonic interface of the Indian and Burmese plates, as well as the active Andaman–Nicobar fault system, and is often capable of generating tsunamis.[41][42] Cyclone preparedness measures are inadequate for the 200,000 residents of Sitakunda who were estimated to be living in high risk areas after the 1991 cyclone. For every 5,000 people, Sitakunda has only one cyclone shelter, each of which is capable of holding 50 to 60 people. Syedpur Union has eleven, Muradpur eight, Baraiyadhala seven, and Kumira five. Sitakunda municipality, Barabkunda, Bhatiary and Bansbaria have four shelters each. Salimpur has three and Sonaichhari Union has two shelters.[43]

The Chittagong Coastal Forest Department developed the river bars (char in Bengali) on the bank of the Sonaichhari channel adjacent to the Sitakunda coast into a kilometer-wide coastal mangrove plantation during 1989–90, to reduce the impact of cyclones.[44] Although the site was initially unstable, rapid sediment accretion stabilised the soil, providing the coast with some protection. The cyclone of 1990 smashed about 25% of a 2-kilometre (1 mi) sea-wall built using two-ton steel-reinforced concrete blocks, some of which were carried up to 100 metres (328 ft) inland. In contrast, a mangrove plantation just south of the sea-wall sustained damage to less than 1% of its trees, most of which recovered within six months.[45] The planted mangrove forest that helped Sitakunda to escape as one of the least damaged areas during the devastating 1991 Bangladesh cyclone is under threat from illegal tree-cutting by ship-breakers in the area.[44]

Annual average temperature is between 32.5 °C (91 °F) and 13.5 °C (56 °F), with an annual rainfall of 2,687 millimetres (106 in).[11] Along with Chittagong and Hathazari, in June 2007 Sitakunda was badly affected by mudslides caused by heavy rainfall combined with the recent practice of hill-cutting.[46][47] The mean annual wind speed recorded in Sitakunda between 1991 and 2001 was 1.8 knots (2 mph),[48] as measured by the wind monitoring station built as part of a wind energy exploration project jointly run by the Local Government Engineering Department and the Bangladesh Center for Advanced Studies.[49] A small 300-watt wind turbine, built by the government, provides electricity to fish farms.[50]

Geology

The geological structure of Sitakunda, 70 kilometres (43 mi) long and 10 kilometres (6 mi) wide, is one of the westernmost structures of Chittagong and Chittagong Hill Tracts, delimited by the Feni River in the north, the Karnaphuli River in the south, the Halda River in the east and the Sandwip Channel in the west.[51] The Sitakunda Range acts as a water divide between the Halda Valley and the Sandwip Channel. The 88 kilometres (55 mi) -long Halda flows from Khagrachari to the Bay of Bangal, and is one of the six tributaries of Karnafuli, the major river in the area.[52] Sandwip Channel represents the northern end of the western part of the Chittagong-Tripura Folded Belt.[53]

The structure contains a thick sedimentary sequence of sandstone, shale and siltstone. The exposed sedimentary rock sequences except limestone, 6,500 metres (21,325 ft) thick in an average, provide no difference in overall lithology of Chittagong and Chittagong Hill Tracts.[51] The Sitakunda fold is an elongated, asymmetrical, box-type double plunging anticline. Both the gently dipping eastern and steeper western flanks of the anticline are truncated abruptly by the alluvial plain of the Feni River.[51] For a lack of infrastructure in Bangladesh, this anticline is one of the few regularly surveyed structures in the country.[54] The syncline from Sitakunda separates the eastern end of the Feni Structure located in the folded flank of the Bengal Foredeep.[51]

Local experts consider the Sitakunda–Teknaf fault to be one of the two most active seismic faults in Bangladesh.[42] After the earthquake of 2 April 1762, which caused a permanent submergence of 155.4 square kilometres (60.0 sq mi) of land near Chittagong and the death of 500 people in Dhaka, two volcanoes are said to have opened in the Sitakunda hills.[55][56] During a seismic tremor on 7 November 2007, fire broke out at the Bakharabad Gas Systems Limited in the Faujderhat area of the upazila when a pipeline was fractured.[57] The Girujan Clay Formation runs through Sitakunda at a thickness of 168 metres (551 ft).[58][59][60] In the Sitakunda hills, the Boka Bil Shale Formation contains Ostrea digitalina, Ostrea gryphoides and numerous plates of Balanus (a type of barnacles), fragments of Arca, Pecten, Trochus, Oliva and corals.[58][61][62] Both formations were identified and named by early 20th-century British petroleum geologist P. Evans.[63]

Demography

According to the census of 2001, Sitakunda had a population of 298,528 distributed to 55,837 units of households (average household size 5.3), including 163,561 men and 134,967 women, or a gender ratio of 121:100. The average population of component administrative units of the upazila are 4,072 for wards, 1,666 for mahallas, 29,853 for unions, 5,060 for mouzas (revenue villages) and 5,060 for villages reported by the census.[32] Out of the 69 mauzas here, 8 have less than 50 households, while 27 have more than 600 households.[32] Of the villages, 8 have a population of less than 250, while 29 have more than 2,500.[32] As of 2001, the population density of Sitakunda was 692 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,792/sq mi).[31]

Apart from the Bengali majority, there are a number of small communities of ethnic minorities in the area. Many of the resident Rakhine people are believed to have settled here during the Arakanese rule of Chittagong (1459–1666), though the event is not historically traceable.[64] The Rakhine population in Khagrachari District migrated from the surrounding area and built up their permanent abode at Ramgarh in the 19th century.[64] Other ethnic groups include the recently migrated Tripuri people.[65] In the District of Chittagong that includes Sitakunda, the population ratio by religion in 2001 was Muslim 83.92%, Hindu 13.76%, Buddhist 2.01% and Christian 0.12%, with 0.19% following other religions. In 1981, it was Muslim 82.79%, Hindu 14.6%, Buddhist 2.23% and Christian 0.21%, with 0.19% following other religions.[66] Chittagonian, a derivative of Bengali spoken by 14 million people mainly in the Chittagong district,[67] is the dominant language.

Administration

Sitakunda as a thana came into existence in 1879, and was renamed to Sitakunda Upazila in 1983.[68] It ranks third in area and sixth in population out of the 26 upazilas and thanas of Chittagong.[32] Sitakunda Town, with an area of 28.63 square kilometres (11.05 sq mi) and a population of 36,650, is the administrative center and the sole municipality (Pourashabha) of Sitakunda Upazila.[69] Shafiul Alam is the mayor of the town, gaining a landslide win over his nearest contender M Abul Kalam Azad in the 2008 mayoral election.[70] The rest of the area is rural and organized into 10 union councils (union parishads), namely Banshbaria, Barabkunda, Bariadyala, Bhatiari, Kumira, Muradpur, Salimpur, Sonaichhari, Saidpur and Bhatiari Cantonment Area.[32] The area is divided into 69 mauzas and 88 villages.[71] Along with neighboring towns such as Hathazari, Fateyabad, Patiya and Boalkhali, Sitakunda Town was developed as a satellite town to relieve the increasing population pressure on Chittagong, with Bhatiari and Sadar unions selected as zones for industrialization, like South Halishahar and Kalurghat.[72] In the 2009 Upazila elections, Abdullah Al Baker Bhuiyan was elected the Upazila Chairman, while Advocate MN Mustafa Nur and Nazmun Nahar were elected vice chairmen.[73]

Sitakunda Upazila makes the 280th electoral district in Bangladesh, identified as Chittagong-3.[74] In the 2008 general election, A.B.M. Abul Kashem Master of Bangladesh Awami League (AL) was elected as the member of parliament, defeating his nearest opponent Mohammad Aslam Chowdhury of Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).[75] In the previous election held in 2001, Siddiki had defeated Kasem.[76] M Akteruzzaman is the Upazila Nirbahi Officer, the chief executive of the upazila.[77] The upazila is served by a court presided over by a first-class magistrate.[78] The Power Development Board is responsible for supplying electricity to the upazila, but due to power outages the industries in the area are strictly constrained.[79] Anwarul Kabir Talukder, the State Minister for Power, lost his job on 29 September 2006 after hundreds of demonstrators in Sitakunda blocked the Dhaka–Chittagong highway in protest at the lack of electricity; violence also erupted elsewhere in Bangladesh.[80][81] In case of fire, the services are brought in from the neighboring city of Chittagong.[82] A proposed Kumira–Sitakunda Hill Water Reservoir Project to supply safe drinking water is to be undertaken by the government.[83]

Economy

The ship breaking industry in Sitakunda has surpassed similar industries in India and Pakistan to become the largest in the world.[1][2] As of August 2007, over 1,500,000 metric tons (1,476,310 long tons) of iron had been produced from the scrapping of about 20 ships in the 19 functional ship yards scattered over 8 square kilometres (3 sq mi) along the coast of Sitakunda 8–10 kilometres (5–6 mi) from Chittagong, near Fouzderhat. Local re-rolling mills, as well as similar mills, process the scrap iron.[29][84][85] Bangladesh, with no local metal ore mining industry of its own, is dependent on ship-breaking for its domestic steel requirements; the re-rolling mills alone substitute for import of about 1,200,000 metric tons (1,181,048 long tons) of billets and other raw materials.[29] There are 70 companies registered as ship breakers in Chittagong, employing 2,000 regular and 25,000 semi-skilled and unskilled workers.[85] Organized under the Bangladesh Ship Breakers Association, (BSBA),[25] these include companies within large local conglomerates that sought ISO certificates.[86]

The industry has come under threat, both from a decline in the number of ships scrapped annually – down from 70–80 to about 20[84] – and because of environmental and work safety concerns.[26] There have been complaints that journalists and human rights activists are being barred from the ship breaking yards.[87] The ship breaking industry is purportedly damaging the local ecology as well, taking a toll on the fish population and soil quality.[88] A survey conducted by students of the Institute of Marine Science of Chittagong University in 2007 revealed that the soil of the locality is polluted by heavy metals including mercury (0.5 to 2.7 ppm), lead (0.5 to 21.8 ppm), chromium (220 ppm), cadmium (0.3 to 2.9 ppm), iron (2.6 to 5.6 ppm), calcium (5.2 to 23.2 ppm) and magnesium (6.5 to 10.57 ppm).[29][89] Safety standards in the industry are low; between 1995 and 2005, 150 workers were killed and 576 were maimed or injured.[90] The main causes of death were fire or explosion, suffocation and inhaling CO2. These old ships also contain hazardous substances like asbestos, lead paint, heavy metals and PCBs.[91] The workers are paid US$1.75 a day and have little access to medical treatment.[92] Among the workers, 41% of are aged between 18 and 22 years,[93] and many are reported to be as young as 10 years of age.[94] There have also been allegations of large quantities of steel and non-ferrous items, such as bronze, aluminum, copper, and bronze-amalgam recovered from ship breaking being smuggled out of Bangladesh.[95] There also are reports of pirates targeting tugboats pulling ships in.[96]

Employment of local people is low in the industrial facilities.[97] The main occupations of the local people by industry are service (28.76%), commerce (21.53%), and agriculture (24.12%).[32] Out of 12,140.83 hectares (30,000.64 acres) of cultivable land 25.46% yield a single crop, 57.95% yield double and 16.59% a treble crop annually. Bean, melon, rubber and betel leaf are the main agricultural exports.[33] Fishing has traditionally been an industry restricted to low caste Hindus belonging to the fisher class, although since the last decades of the 20th century an increasing number of Muslims have joined the sector.[98] Due to the introduction of engine-powered boats and gill nets, there was a rise in fish catches between the 1970s and 1990s, especially in the major fishing season (mid-July to mid-November).[98] Over-fishing, however, has depleted the fish population and some fish species are facing extinction in the area, leading to seasonal food insecurity (February to April).[98] According to a 2001 survey, 4,000 people in Sitakunda were engaged in wild shrimp fry collection, harvesting an average of five-and-a-half million fries a year.[99]

Sitakunda has a cement factory, 12 jute mills, 6 textile mills, 10 re-rolling mills, and 79 functional and defunct shipyards.[33][84] Two of the operational jute mills are run by the Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation,[100] and one has been sold to a private sector company.[101] To protest against privatization, workers of Hafiz Jute Mill, Gul Ahmed Jute Mill, MM Jute Mill and RR Jute Mill blocked the Dhaka–Chittagong Highway for seven hours in September 2007.[102] As early as 1953, Sitakunda was described as the location for one of only five poultry farms in East Pakistan, along with Tejgaon (Dhaka), Narayanganj (Dhaka), Jamalpur (Bogra), and Sylhet.[103] Some mining for sand from agricultural lands is carried out along the eastern side of the Dhaka–Chittagong road.[104] Operators of local brick kilns are engaged in illegal hill cutting, a practice that was responsible along with heavy rainfall for the 2007 Chittagong mudslide.[47][105] The rural poor are supported by Grameen Bank and NGOs such as CARE, BRAC and ASA.[33][106]

Transport and communication

The Dhaka–Chittagong Highway runs through Sitakunda, connecting the two largest cities in Bangladesh. A workshop conducted by Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated that improving the highway would increase Bangladesh's GDP by 1% and its foreign trade by 20%.[107] This roadlink between the two cities existed in the pre-railway days[108] and has been identified as a part of the medieval southern Silk Road.[109] In 2006, ADB and the World Bank announced a plan to help Bangladesh build a second highway between Dhaka and Chittagong,[110] which would be a part of the Asian Highway Network.[111]

Historically, the rail transportation system drove developments in Chittagong and the surrounding areas, including Sitakunda.[72] The rail tracks were established as part of the Bengal Assam Railway in 1898, originally running from Chittagong to Badarpur, with branches to Silchar and Laksam.[108] In September 1878, Sitakunda was included in the East Bengal Circle of Railway Mail Service (RMS) along with rest of the district.[112] By 1904, the track system was extended to Chandpur to connect river boat traffic between Goalanda and Kolkata.[108] Approximately 37 kilometres (23 mi) of railroads stop at six rail stations.[33] Currently, there is no express train service between Sitakunda and Chittagong, though intercity expresses (Sylhet–Chittagong, Chandpur–Chittagong, and Dhaka–Chittagong) stop at Sitakunda station and carry a small share of the commuter traffic load.[72] By 2003, there were a total of 112 kilometres (70 mi) of paved roads in the upazila, along with 256 kilometres (159 mi) of mud roads, as well as five ferry-gauts or river docks for the use of barge-type ferryboats. The traditional bullock carts are now rarely seen in the upazila.[33]

Sitakunda was to be the landing station for a submarine communications cable, but the cable now comes ashore at Cox's Bazar.[113] The cable has frequently been severed by miscreants, often in the Sitakunda area, since its installation on 21 May 2006.[114] Bangladesh NGOs Network for Radio and Communication (BNNRC) has brought internet services to the upazila by establishing Rural Knowledge Centres (RKC).[115] BTTB and RanksTel run telephone services in the upazila. The telephone area code for Sitakunda is 3028, which has to be added to Bangladesh area code +880 when making overseas calls, and the subscriber numbers consist of four digits locally.[116]

Pilgrimage sites

Sitakunda is a major site for pilgrimage in Bangladesh, as it features 280 mosques (including the Shah Mosque) 8 mazars (including Baro Awlias Mazar, Kalu Shah Mazar, Fakir Hat Mazar, Shahjahani Shah Mazar), 49 Hindu temples (including Labanakhya Mandir, Chandranath Mandir, Shambunath Mandir), 3 ashrams (including Sitakunda Shankar Math), and 3 Buddhist temples.[33] The Hammadyar Mosque, located at the village of Masjidda on the banks of a tank[117] known as the Hammadyar Dighi, was built during the reign of Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah, the last Husain Shahi sultan of Bengal, as recorded by the inscription above the central entrance.[118] The Sudarshan Vihara at village Mayani here, as well as the Vidarshanaram Vihara at village Mayani in Patiya were both established in 1922 by Prajnalok Mahasthavir (1879–1971), an eminent Bangladeshi Buddhist preacher.[119]

According to legend, Shiva's wife Sati immolated herself in the yajna-fire of her father Daksha, as a protest against Shiva's dishonor. The God became furious and started to dance the Tāndava with Sati's body on his shoulders.[120] Knowing that the dance of destruction was about to annihilate the world, Vishnu cut the body of Sati to pieces with Sudarshana Chakram, his celestial weapon, thereby appeasing Shiva.[120] Each of 51 pieces of the body fell to earth, and the place where each piece fell became a holy center of pilgrimage or Shakti Peetha.[120] The legend goes that Sati's right arm fell near a now-extinct hot spring at the Chandranth peak in Sitakunda. The site is marked by the temple of Sambhunath just below the Chandranath temple on top of the peak, and it is a major tirtha for Hindus in Bangladesh.[121][122]

According to Rajmala, the temple of Chandranath received considerable endowments from the Twipra Kingdom in the time of king Dhanya Manikya, who once attempted to remove the lingam from the temple to his kingdom.[5][123] Poets from across the ages – from Jayadeva (circa 1200 AD) to Nabinchandra Sen (1847–1909) – were said to be devoted to the temple.[5][123] Chandranath is within the jurisdiction of Gobardhan Math, which was founded, according to legends, by Padmacharya, a disciple of Shankaracharya and founder of Vana and Aranya sects of the Dashanami Sampradaya.[5][123] An International Vedic Conference was held from 15 to 17 February 2007 at Sitakunda Shrine (Tirtha) Estate in Sitakunda Chandranath Dham, on the occasion of the great Shiva Chaturdarshi (a Hindu festival in worship of Lord Shiva).[5][123] These temples have been subject to repeated attack and violation by Muslims,[124] and Bangladesh Hindu Bouddha Christian Oikya Parishad has asked for the pilgrims to be protected.[125]

Flora and fauna

_in_Sitakunda1.jpg.webp)

While returning to Kolkata after completing a floral survey, Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817–1911) carried out the first survey of Sitakunda's local flora, as recorded in his Himalayan Journals, in January 1851 (published by the Calcutta Trigonometrical Survey Office and Minerva Library of Famous Books; Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., 1891).[126]

The forests of the region are known to be evergreen type with a preponderance of deciduous species with a levelled distribution.[126] The topmost level consists of Garjan (Dipterocarpus alatus), Telsur (Hopea odorata), Chapalish (Artocarpus chaplasha), Chundul (Tetrameles nudiflora) and Koroi or the Moluccan albizia (Falcataria moluccana). The lower level consists of species of Jarul (Lagerstroemia speciosa), Toon (Toona ciliata), Jam (Syzygium cumini), Jalpai (Elaeocarpus robustus) and Glochidion. Lianas, epiphytes (mostly of orchids, asclepiads, ferns and leafy mosses) and herbaceous undergrowths are abundant.[126] Savannah formations are found in the open, along the banks of rivers and swamps with common tall grasses like Kans (Saccharum spontaneum), Shon (Imperata cylindrica and I. arundincca) and Bena (Vetiveria zizanoides).[126] Several species of Bamboo are cultivated that are common in Bangladesh including Bambusa balcooa (which is also common in Assam), B. vulgaris, B. longispiculata, B. tulda and B. nutans; the latter two also being common in the hills of the region.[127]

A number of fish species have become endangered in the area due to overfishing.[98] They include Bhoal (Raiamas bola), Lakkhya (Eleutheronema tetradactylum), Chapila (Gudusia chapra), Datina (Acanthopagrus latus), Rupchanda (Pampus argenteus), Pungash (Pangasius pangasius), Chhuri (Trichiurus lepturus), Ilsha Chandana (Tenualosa toli), Hilsha (Tenualosa ilisha), Faishya (Anchoviella commersonii), Maittya (Scomberomorus commerson), Gnhora (Labeo gonius), Kata (Nemapteryx nenga), Chewa (Taenioides cirratus), Sundari bele (Glossogobius giuris), Bnata (Liza parsia), Koral (Etroplus suratensis) and Kawoon (Anabas testudineus), as well as crustaceans like tiger shrimps.[128]

The first eco-park in Bangladesh, Sitakunda Botanical Garden and Eco Park, was established in 2001 along with a botanical garden, under a five-year (2000–2004) development project at a cost of Tk 35.7 million on 808 hectares (1,997 acres) of the Chandranath Hills in Sitakunda.[129] The eco-park was established to facilitate biodiversity conservation, natural regeneration, new plantations and infrastructure development, as well as to promote nature-based tourism to generate income. The park, 405 hectares (1,001 acres), and the garden, 403 hectares (996 acres), under the Bariadhala Range of Chittagong Forest Division, are rich with natural Gymnosperm tree species including Podocarpus neriifolius and species of Gnetum and Cycas.[37] The park is reported to be able to receive 25,000 visitors in a single weekend.[130] With the botanical garden included, the number of visitors can reach up to 50,000.[131] According to the International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management, however, "ignoring the dependence of local people on park resources created conflicts between local communities and the park authority" and "prohibition on the extraction of forest products from the park... make the livelihoods of surrounding villagers vulnerable".[132]

Society

The educational institutions of the upazila include Faujdarhat Cadet College (founded in 1958), 4 regular colleges (including Sitakunda Degree College founded in 1968), 24 high schools (including Sitakund Government Model High School founded in 1913 and Madam Bibir Hat Shahjania High School founded in 1905), 10 madrasas, and 76 junior and primary schools.[33] All the secondary schools and regular colleges are under the Chittagong Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education split from the Comilla Board in May 1995.[133] Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah (1885–1969), an eminent Bangladeshi linguist, served as the headmaster of the Government High School from 1914 to 1915.[134] On 24 July 1996, members of Bangladesh Chhatra League and Bangladesh Islami Chhatra Shibir (ICS) in Sitakunda Degree College fought with guns and firecrackers over a minor dispute.[135] On 29 July 1996, two ICS members of the college were abducted and one of them was killed.[135][136] Faujdarhat Cadet College and Bangladesh Military Academy are also situated in this upazila. As of 2001, average literacy of Sitakunda Upazila for people of 7 years of age or more is 54.6%,[31] while the average literacy of Sitakunda Pourashabha is 53.9%.[69] There has been an overall growth of 32.9% between 1991 and 2001, which for men was 20.5% and for women 59.2%.[32] 70,315 people of the Upazila between the ages of 5 and 24 years attend schools, an overall increase of 35.6% between 1991 and 2001, which for men was 28.1% and for women 45.4%.[32] The highest school attendance rate is observed in age group 10–14 years.[32]

The health service centers in the upazila include a health complex, an infectious diseases hospital, a railway TB hospital, 11 family planning centres and a veterinary treatment centre.[33] Bangladesh Railway set up the hospital at Kumira in 1952 with a capacity of 150 beds. The capacity was reduced to 50 beds in 1994 as some focus was redirected to the Railway Hospital at Central Railway Building in Chittagong. Originally built to treat railway employees, the hospital now also treats people from the wider community.[137] Malaria, dengue and other fevers, hepatitis, as well as respiratory infections including tuberculosis are some of the major health threats.[24] The percentage of disabled in Sitakunda is reported to be the highest in Bangladesh, at 17% compared to the national average of 13%.[97]

Banshbaria Union has been declared as 100% sanitized, as all households in the union adopted sanitary latrines,[138] while the upazila has only 16% sanitation coverage.[139] A survey published in 2006 by the Bangladesh Arsenic Mitigation Water Supply Project found that of the 18,843 tube wells surveyed, 24.7% were found to be contaminated. Visible signs of arsenic poisoning were found in 47 people.[140]

National newspapers published in Dhaka including Prothom Alo, Ajker Kagoj, Janakantha and The Daily Ittefaq are available in Sitakunda, as well as regional newspapers published in Chittagong Azadi and Purbakon. It also has its own local newspapers and a journalist community.[141] In 2003, Atahar Siddik Khasru, the president of the local Press Club, went missing on 30 April and was rescued on 21 May.[142] He was abducted and tortured by unidentified men allegedly on charges of protesting against the harassment of Mahmudul Haq, editor of local magazine Upanagar.[142][143] On 6 May, about 30 local journalists working for national and local press took to the streets in protest.[142] The other weekly newspaper is Chaloman Sitakunda.[33] Television channels available in the upazila include satellite television channels like Channel i, ATN Bangla, Channel One, NTV, as well as terrestrial television channel Bangladesh Television.[141]

The festivals of Shiva Chaturdashi in middle of the month of Falgun (end of February) and Chaitra Sankranti at end of the month of Chaitra (mid April) are observed with much fanfare, featuring the largest Hindu fair of the district.[33][144] The Sitakunda Upazila Krira Sangstha (Sports Club) is noted for its participation in soccer.[145] There are 151 clubs, a public library and two cinema halls in the upazila.[33]

See also

References

- Aslam, Syed M. (23 April 2001), Ship-breaking industry: Uncertain future, Pakistan Economist

- "Shock Waves Demolish Alang", Times Shipping Journal, March 2004, archived from the original (Web archive copy) on 22 February 2005, retrieved 28 October 2008

- Jama'atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB): Incidents, South Asia Terrorism Portal, retrieved 28 October 2008

- "The deadly terror outfit, rise of its kingpins", The Daily Star, 31 March 2007

- Dev, Prem Ranjan (17 February 2007), "Point Counter-Point: Of Shiva Chaturdashi and Sitakunda", The Daily Star

- Minorities in Pakistan, Karachi: Pakistan Publications, 1964, p. 20

- Bangladesh: The Roots, Bangladesh WWW Virtual Library, Asian Studies Network Information Center, International Information Systems, University of Texas at Austin, archived from the original on 30 January 2007, retrieved 27 August 2007

- Ahsan, Syed Mohammad Kamrul (2012), "Prehistory", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Bandopadhyay, Rakhaldas (1971), Banglar Itihas (History of Bengal), Kolkata: Naba Bharat Publishers

- Brown, J. Coggin; Marshall, John Hubert (1988), Prehistoric antiquities of India preserved in the Indian museum at Calcutta, New Delhi: Cosmo Publications

- Harun, Jasim Uddin (2012), "Chittagong District", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Chittagong through the ages, Chittagong Port Authority, archived from the original on 15 February 2008, retrieved 3 March 2008

- Khan, Sadat Ullah (2012), "Arakan", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Barua, Rebatapriya (2012), "Ramkot Banashram", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Karim, K M (2012), "Shahjahan", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Osmany, Shireen Hasan (2012), "Chittagong City", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Yust, Walter, ed. (1952), Encyclopædia Britannica: A New Survey of Universal Knowledge, 4, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., p. 427, OCLC 930908

- Khan, Shafiqur Rahman (Spring 2003), Indigenous Peoples' In Bangladesh: Land Rights and Land Use In The Context of Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) (PDF), Faculty of Law, Lund University, retrieved 12 May 2008 (Master's thesis).

- Van Schendel, Willem (1798), Francis Buchanan in Southeast Bengal, Dhaka: University Press Limited

- Ghosh, Aurobindo (27 March 1908), "Asiatic Democracy", Bande Mataram, Apurba Krisna Bose

- Prescot, Rupert, Sedition and political control: The ideological paradox of British responses to Indian nationalism (PDF), University of Leeds, retrieved 12 May 2008

- Ahmed, Kazi Matin Uddin (2012), "Wildcat Well", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Imam, Badrul (2012), "Hydrocarbon Exploration", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Maruf Hossain, Dr. Md. M; Islam, Mohammad Mahmudul (2006), Ship Breaking Activities and its Impact on the Coastal Zone of Chittagong, Bangladesh: Towards Sustainable Management (PDF), Young Power in Social Action, ISBN 978-984-32-3448-3

- Sea polluted under authorities' nose, Bangladesh News, 31 July 2007, archived from the original on 7 February 2012

- 60 minutes: The Ship Breakers Of Bangladesh, CBS News, 5 November 2006

- Sinha, Dinesh Chandra, ed. (2012). ১৯৫০: রক্তরঞ্জিত ঢাকা বরিশাল এবং [1950: Bloodstained Dhaka Barisal and more] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Codex. p. 71.

- Kamra, A.J. (2000). The Prolonged Partition and its Pogroms: Testimonies on Violence Against Hindus in East Bengal 1946-64. New Delhi: Voice of India. p. 67. ISBN 978-81-85990-63-7.

- "Shipbreaking threatens environment along Ctg coastal areas", The Daily Independent, 24 August 2007, archived from the original on 28 September 2007

- Huq, Asharaful (29 September 2005), Police reveal starling facts about bigots' operations, Daily News Monitoring Service, retrieved 6 September 2007

- Area, Population and Literacy Rate by Upazila/Thana-2001 (PDF), Population Census Wing, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2010, retrieved 3 September 2007

- Community Report: Chittagong Zila (PDF), Population Census Wing, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, June 2012, retrieved 29 December 2015

- Chowdhury, Shimul Kumar (2012), "Sitakunda Upazila", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Chowdhury, Masud Hasan (2012), "Physiography", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Promotion of renewable energy, energy efficiency and greenhouse gas abatement: Bangladesh (Country Report) (PDF), Asian Development Bank, 2003, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2007

- Market Report on Renewable Energy Technologies in Bangladesh (PDF), Dhaka: Prokaushali Sangsad Limited, 23 February 2006, retrieved 2 March 2008

- Kamal Uddin, A. M., Areas with special status in the coastal zone (Working Paper WP030) (PDF), Program Development Office for Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2004

- Sharmeen, Tania (26 October 2007), "Heritage Foundation starts journey", Weekly Holiday, archived from the original on 10 June 2011

- Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Bangladesh: A Policy Review (PDF), UK Department for International Development, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2004

- Cyclones in Bangladesh, Bangladesh Water Development Board, archived from the original on 19 February 2008, retrieved 28 January 2008

- Islam, Rafiqul, Pre- and post-tsunami coastal planning and land-use policies and issues in Bangladesh, Food and Agriculture Organization, retrieved 8 September 2007

- "Bangladesh runs high risk of quake, tsunami", The Daily Star, 21 October 2005

- Alamgir, Nur Uddin (23 August 2006), "Two lakh live in high-risk areas of cyclone-prone Sitakunda", The Daily Star, retrieved 28 January 2008

- "Ship-breakers clear Sitakunda mangroves", The Daily Star, BSS, 24 December 2005, retrieved 21 September 2007

- McConchie, D.; P. Saenger (1991), "Mangrove forests as an alternative to civil engineering works in coastal environments of Bangladesh: lessons for Australia", in Arakel, A.V. (ed.), Proceedings of 1990 Workshop on Coastal Zone Management, Yeppoon, Queensland, pp. 220–233

- Death toll in mudslide rises to 84 in southeastern Bangladesh, ReliefWeb, Xinhua News Agency, 12 June 2007

- Choudhury, Iqbal Hossain (13 June 2007), "পাহাড়ে বিভীষিকা", Chutir Dine, Prothom Alo (in Bengali), 403, pp. 4–6

- Khan Y.S.A.; Hossain M.S., Chowdhury M.A.T. (2003), Resource inventory and land use mapping for integrated coastal environment management: remote sensing, GIS and RRA approach in greater Chittagong coast, Ministry of science and information & communication technology, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

- Wind Energy Resource Mapping (WERM) in Bangladesh, Wind Energy Development Project, Sustainable Rural Energy Program, Local Government Engineering Department, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, archived from the original on 14 August 2007, retrieved 25 August 2007

- Bouma, Jan Jaap; Jeucken, Marcel; Klinkers, Leon (2001), Sustainable Banking: The Greening of Finance, Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf, ISBN 978-1874719380

- Baqui, M. A. (2012), "Geological Structure", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Faruque, H. S. Mozaddad (2012), "Chittagong Region River System", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Alam, A.K.M. Khorshed; Chowdhury, Sifatul Quader (2012), "Chittagong-Tripura Folded Belt", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Woobaidullah, A.S.M. (2012), "Geological Survey", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Disaster Prevention: Earthquake, The Sustainable Development Networking Program (SDNP), archived from the original on 6 February 2012, retrieved 25 August 2007

- Chowdhury, Sifatul Quader; Khan, Aftab Alam (2012), "Earthquake", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- M5.2 Roninpara Earthquake, Amateur Seismic Centre, 30 December 2007, archived from the original on 9 May 2008, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Chowdhury, Sifatul Quader; Khan, Mujibur Rahman; Uddin, Md Nehal (2012), "Geological Group-Formation", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Kent, W. N.; Hickman, R. G.; Gupta, U. D. (2002), "Application of a Ramp/Flat-Fault Model to Interpretation of the Naga Thrust" (PDF), AAPG Bulletin, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 86, doi:10.1306/61eeddf0-173e-11d7-8645000102c1865d, retrieved 24 August 2007

- Large sedimentation rate in the Bengal Delta (PDF), The Geological Society of America, retrieved 24 August 2007

- Zaih, K.M.; Uddin, A (April 2004), Influence of overpressure on formation velocity evaluation of Neogene strata from the eastern Bengal Basin (PDF), Department of Geology and Geography, Auburn University, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2005, retrieved 24 August 2007

- Miocene sedimentation and subsidence during continent–continent collision, Bengal basin (PDF), Auburn University, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2013, retrieved 24 August 2007

- Evans, P. (1964), "The tectonic framework of Assam", Journal of the Geological Society of India, 5

- Hasan, Kamrul (2012), "Rakhain, The", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- Resource Use by Indigenous Community in the Coastal Zone; Kamal, Mesbah (PDF), Research and Development Collective (RDC), July 2001, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2007, retrieved 28 August 2007

- Zilawise Percentage Distribution of Bangladesh Population by Religious Communities, Religious Composition, Ministry of Planning, Government of Bangladesh, retrieved 24 December 2007

- Gordon Jr., Raymond G. (2005), Ethnologue: Languages of the World (15th edition), Dallas, Texas: SIL International, ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6, archived from the original on 24 February 2007

- Land Use Plan of Sitakunda Paurashava, Urban Development Directorate, Government of Bangladesh, 2006, archived from the original on 15 February 2010, retrieved 28 August 2007

- Area, Population and Literacy Rate by Paurashava – 2001, Population Census Wing, BBS, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009, retrieved 23 September 2007

- News Desk (6 August 2008), "AL beats BNP in 8 of 9", The Independent, Dhaka, retrieved 28 January 2009

- "District Statistics 2011: Chittagong" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Chowdhooree, Imon; Das, Kanu Kumar (8 April 2005), "Urban mass transportation for Chittagong - I", The Daily Star, retrieved 18 September 2007 (Urban Page).

- News Desk (23 January 2009), AL supported candidates secure victory in 14 upazilas in Ctg, Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha, retrieved 28 January 2009

- Constituency Maps of Bangladesh (PDF), Bangladesh Election Commission, 2010, retrieved 13 August 2014

- "District-wise JS poll results supplied by the news agency BSS Tuesday", The Financial Express, Dhaka, 31 December 2008

- Voting by constituency People's Republic of Bangladesh: National Legislative Election 2001, Adam Carr's Election Archive, retrieved 27 December 2007

- "Voter registration begins in 2 Ctg pourashavas", The Daily Star, Dhaka, BSS, 24 August 2007, retrieved 27 December 2007

- Hoque, Kazi Ebadul (2012), "Magistrate", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Most areas in Ctg still under darkness; PDB fails to repair Khulshi sub-station, News Network, 26 June 2005, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Staff Correspondent (26 October 2006), "Outrage for power on outside Dhaka", New Age, archived from the original on 14 October 2007, retrieved 2 March 2008

- Staff Correspondent (26 October 2006), "Talukder dismissed after resignation announcement", New Age, archived from the original on 14 October 2007, retrieved 2 March 2008

- "Girl burnt alive, 87 houses gutted", The Daily Star, UNB, 31 January 2006, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Status of Water & Sanitation Services in Chittagong Water Supply and Sewerage Authority, Bangladesh (PDF), Capacity Building Workshop on Partnerships for Improving the Performance of Water Utilities in the Asia and the Pacific Region, United Nations Development for Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), retrieved 29 December 2007

- Institutional Aspects of Ship Breaking Industry in Bangladesh (PDF), Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan Project, Water Resources Planning Organization (WARPO), Ministry of Water Resources, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2007, retrieved 25 August 2007

- Ataur Rahman; AZM Tabarak Ullah, Ship Breaking: A Background Paper, Programme on Safety and Health at Work and the Environment (SafeWork), International Labour Organization, retrieved 25 August 2007

- Official Website, PHP Ship Breaking & Re-cycling Ind. Ltd., archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 25 August 2007

- "Journalists, HR activists not allowed inside ship-breaking yard", New Age, 18 March 2006, archived from the original on 28 September 2007, retrieved 6 September 2007

- The Continuous Evasion Of The "Polluter Pays Principle (PDF), Greenpeace, September 2002, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007, retrieved 3 September 2007

- DNV-Report: Shipbreaking Practices: On site assessment Chittagong, Bangladesh (PDF), Greenpeace, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2009, retrieved 25 August 2007

- Staff Correspondent (1 June 2005), "Greens concerned about safety in ship breaking industry", New Age, archived from the original on 30 July 2007, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Facing the Deadline (DOC), InterTanko, 16 April 2002, retrieved 29 December 2007

- "Feature: Workers of ship breaking industry in Bangladesh gasping for survival", People's Daily, 21 March 2007, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Daily Collection of Maritime Press Clippings 2005-138 (PDF), MaritimeDigital Archive Portal, Frederic Logghe, 1 June 2005, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2006

- Nurul Haque, A.N.M. (24 November 2004), "Child labour in Bangladesh", The New Nation, retrieved 30 December 2007 – via Timesizing News

- Bangladesh: Shipbreakers Pollute with Impunity, The Rapid Results College Limited, Autumn 2006, archived from the original on 20 August 2008, retrieved 30 December 2007

- Bruce A. Elleman, Andrew Forbes and David Rosenberg, "Piracy and Maritime Crime", page 124, Naval War College

- Wealth of Trans National Corporations and the vision of localization, Zakaria: One World South Asia, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 2 February 2009

- Kleih, Ulrich; Alam, Khursid; Dastidar, Ranajit; Dutta, Utpal; Oudwater, Nicoliene; Ward, Ansen (January 2003), Livelihoods in Coastal Fishing Communities, and the Marine Fish Marketing System of Bangladesh (PDF), retrieved 3 September 2007

- Frankenberger, Timothy R. (August 2002), Livelihood Analysis of Shrimp Fry Collectors in Bangladesh: Future Prospects in Relation to a Wild Fry Collection Ban, TANGO International Inc., archived from the original (DOC) on 10 August 2003, retrieved 8 September 2007

- BJMC, Ministry of Jute, Government of Bangladesh, archived from the original on 8 June 2004, retrieved 3 September 2007

- Privatisation of textile mills turns sour in Ctg, The New Nation, 30 August 2005, archived from the original on 9 October 2007, retrieved 6 September 2007

- Staff Correspondent (8 September 2007), "Jute millers block up Dhaka-Ctg Highway", New Age, archived from the original on 9 December 2007, retrieved 20 December 2007

- Pakistan, Pakistan Department of Advertising, Films and Publications, 1953, p. 156

- Bangladesh & Desertification, SDNP Bangladesh, archived from the original on 6 February 2012, retrieved 3 September 2007

- Alam, Nurul (8 July 2007), "DoE to initiate fresh survey to list illegal hill cutters", New Age, archived from the original on 15 October 2007, retrieved 8 July 2007

- Huda, Shamsul (2012), "ASA", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- News Release, Improving Logistics in Dhaka-Chittagong Corridor Can Raise GDP by 1%, ADB, archived from the original on 7 June 2011, retrieved 25 January 2008

- Mukherjee, Hena (2012), "Assam Bengal Railway", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Rehman, Sobhan (2000), Rediscovering the Southern Silk Route: Integrating Asia's Transport, University Press Limited, p. 139, ISBN 978-984-05-1519-6

- Syeduzzaman, M (24 July 2006), "Fools rush in", The Daily Star, retrieved 25 January 2008

- Bangladesh Study Report (PDF), UNESCAP, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011, retrieved 3 March 2008

- Khan, Ishtiaque Ahmed (2012), "Postal Communication", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Staff Correspondent (25 July 2006), "Joy for e-governance to curb corruption", New Age, archived from the original on 23 August 2010, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Rahman, Sayeed (13 November 2007), "Bangladesh Submarine cable link sabotaged again", Media & Tech, Ground Report, retrieved 7 February 2009

- Rural Knowledge Center provide Data Operators to the Voter Registration and National ID Card Program and facilitate in the motivational campaign, Bangladesh NGOs Network for Radio and Communication, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Numbering Plan, Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC), 2006, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Tank is a term that was used in colonial times for a man-made body of water or reservoir (dighi).

- Hossain, Shamsul (2012), "Hammadya Mosque", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Bhikkhu, Sunithananda (2012), "Mahasthavir, Prajnalok", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Kinsley, David (1988), Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06339-6

- Togawa, Masahiko (2012), "Sakta-pitha", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Chowdhury, Sifatul Quader (2012), "Hot Spring", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Dev, Prem Ranjan (16 February 2007), Sitakunda Shrine and Shiba Chaturdarshi Festival, The New Nation, p. Editorial Page, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 27 August 2007

- Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora (PDF), Hindu American Foundation, 11 June 2007, retrieved 3 September 2007

- Memorendum to SAARC Ministers Bulletin, Bangladesh Hindu Bouddha Christian Oikya Parishad, May 2006, archived from the original on 2 May 2009, retrieved 24 December 2007

- Zuberi, M. Iqbal (2012), "Flora", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Vivekanandan, K.; Rao, A.N.; Rao, V. Ramanatha, eds. (1998), Bamboo and Rattan Genetic Resources in Certain Asian Countries (PDF), IPGRI, International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR), ISBN 978-92-9043-3644, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2015, retrieved 18 September 2007

- For name alternatives see "List of Common Names of fish of Bangladesh". SeaLifeBase. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. (list)

- Khair, Abul (2012), "Ecopark", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Roy, Monoj K.; Philip J. DeCosse (March 2006), "Managing demand for protected areas in Bangladesh: poverty alleviation, illegal commercial use and nature recreation" (PDF), Policy Matters, IUCN Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy, vol. 14, retrieved 18 September 2007

- Anderson, Glen; A.H.M. Mostain Billah, Review of Issues and Options for the Sustainable Financing of Protected Areas Management in Bangladesh (PDF), United States Agency for International Development, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2008, retrieved 18 September 2007

- Nath, T.K; M. Alauddin (March 2006), "Sitakunda botanical garden and eco-park, Chittagong, Bangladesh: Its impacts on a rural community", The International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management, 2 (1): 1–11, doi:10.1080/17451590609618095, S2CID 84574761

- Official Website, Chittagong Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, archived from the original on 29 April 2008, retrieved 27 December 2007

- Badiuzzaman, Muhammad (2012), "Shahidullah, Muhammad", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, ISBN 978-984-32-0576-6

- Issue Paper: Bangladesh Human Rights Situation, Immigration and refugee Board of Canada, January 1997, archived from the original on 25 April 2005, retrieved 26 December 2007

-

"Shibir worker hacked to death in Sitakundu", The Bangladesh Observer, p. 1, col. 5, 31 July 1996,

One activist of the Islami Chhatra Shibir was hacked to death and another seriously injured by some rival political activists at Shitakunda College on Monday afternoon.

- Chaudhury, Tushar Hayat (10 April 2005), "Chest Disease Hospital in Ctg in bad shape", New Age, p. Metro, archived from the original on 17 December 2005, retrieved 18 September 2007

- Changing Lives: Community Based Advocacy (PDF), Rural Advocacy Program Water Aid Bangladesh, February 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2012, retrieved 3 September 2007

- Summary Environmental Impact Assessment (PDF), Road Maintenance and Improvement Project, People’s Republic of Bangladesh, July 2000, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2012, retrieved 8 September 2007

- Upazila wise Summary Results (PDF), Bangladesh Arsenic Mitigation Water Supply Project (BAMWSP), p. 1, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2005, retrieved 29 December 2007

- Chakroborty, Shadhak Kumar (2002), Bangladesh National Media Survey, Bangladesh Center for Communication Programs

- Bangladesh – 2004 Annual Report: A journalist abducted, Reporters Without Frontiers, archived from the original on 22 November 2006, retrieved 26 December 2007

- Attacks on the Press: Bangladesh, Committee to Protect Journalists, archived from the original on 8 March 2013, retrieved 26 December 2007

- Haque, Mahbubul (1981), Chittagong Guide: Tourist, Industrial, Shipping & Business Guide, Barnarekha, Dhaka, p. 85

- Bangladesh, Country Directory, Club Soccer, archived from the original on 2 October 2011, retrieved 27 December 2007