Stanozolol

Stanozolol (abbrev. Stz), sold under many brand names, is an androgen and anabolic steroid (AAS) medication derived from dihydrotestosterone (DHT). It is used to treat hereditary angioedema.[12][6][1][7] It was developed by American pharmaceutical company Winthrop Laboratories (Sterling Drug) in 1962, and has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for human use, though it is no longer marketed in the USA.[7][8] It is also used in veterinary medicine.[1][7] Stanozolol has mostly been discontinued, and remains available in only a few countries.[1][7] It is given by mouth in humans or by injection into muscle in animals.[7]

| |||

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trade names | Many[1] | ||

| Other names | Androstanazol; Androstanazole; Stanazol; WIN-14833; NSC-43193; NSC-233046; 17α-Methyl-2'H-5α-androst-2-eno[3,2-c]pyrazol-17β-ol; 17α-Methylpyrazolo[4',3':2,3]-5α-androstan-17β-ol | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information | ||

| Pregnancy category |

| ||

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection (veterinary)[2] | ||

| Drug class | Androgen; Anabolic steroid | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status |

| ||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | High[3] | ||

| Metabolism | Liver[4] | ||

| Elimination half-life | Oral: 9 hours[5] IM: 24 hours (aq. susp.)[5][2] | ||

| Duration of action | IM: >1 week[4] | ||

| Excretion | Urine: 84% | ||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.801 | ||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

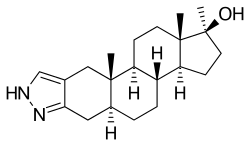

| Formula | C21H32N2O | ||

| Molar mass | 328.500 g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| |||

| |||

| (verify) | |||

Unlike most injectable AAS, stanozolol is not esterified and is sold as an aqueous suspension, or in oral tablet form.[7] The drug has a high oral bioavailability, due to a C17α alkylation which allows the hormone to survive first-pass liver metabolism when ingested.[9][7] It is because of this that stanozolol is also sold in tablet form.[7]

Stanozolol is one of the AAS commonly used as performance-enhancing drugs and is banned from use in sports competition under the auspices of the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) and many other sporting bodies. Additionally, stanozolol has been used in US horse racing.[10][11]

Medical uses

Stanozolol has been used with some success to treat venous insufficiency. It stimulates blood fibrinolysis and has been evaluated for the treatment of the more advanced skin changes in venous disease such as lipodermatosclerosis. Several randomized trials noted improvement in the area of lipodermatosclerosis, reduced skin thickness, and possibly faster ulcer healing rates with stanozolol.[12][13] It is also being studied to treat hereditary angioedema, osteoporosis, and skeletal muscle injury.[14][15]

Non-medical uses

Stanozolol is used for physique- and performance-enhancing purposes by competitive athletes, bodybuilders, and powerlifters.[7]

Side effects

Side effects of stanozolol include virilization (masculinization), hepatotoxicity,[7] cardiovascular disease, and hypertension.[16]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Medication | Ratioa |

|---|---|

| Testosterone | ~1:1 |

| Androstanolone (DHT) | ~1:1 |

| Methyltestosterone | ~1:1 |

| Methandriol | ~1:1 |

| Fluoxymesterone | 1:1–1:15 |

| Metandienone | 1:1–1:8 |

| Drostanolone | 1:3–1:4 |

| Metenolone | 1:2–1:30 |

| Oxymetholone | 1:2–1:9 |

| Oxandrolone | 1:3–1:13 |

| Stanozolol | 1:1–1:30 |

| Nandrolone | 1:3–1:16 |

| Ethylestrenol | 1:2–1:19 |

| Norethandrolone | 1:1–1:20 |

| Notes: In rodents. Footnotes: a = Ratio of androgenic to anabolic activity. Sources: See template. | |

As an AAS, stanozolol is an agonist of the androgen receptor (AR), similarly to androgens like testosterone and DHT.[7][17] Its affinity for the androgen receptor is about 22% of that of dihydrotestosterone.[18] Stanozolol is not a substrate for 5α-reductase as it is already 5α-reduced, and so is not potentiated in so-called "androgenic" tissues like the skin, hair follicles, and prostate gland.[7][17] This results in a greater ratio of anabolic to androgenic activity compared to testosterone.[7][17] In addition, due to its 5α-reduced nature, stanozolol is non-aromatizable, and hence has no propensity for producing estrogenic effects such as gynecomastia or fluid retention.[7][17] Stanozolol also does not possess any progestogenic activity of significance.[7][17] Because of the presence of its 17α-methyl group, the metabolism of stanozolol is sterically hindered, resulting in it being orally active, although also hepatotoxic.[7][17]

Pharmacokinetics

Stanozolol has high oral bioavailability, due to the presence of its C17α alkyl group and the resistance to gastrointestinal and liver metabolism that it results in.[3][19][20] The medication has very low affinity for human serum sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), about 5% of that of testosterone and 1% of that of DHT.[21] Stanozolol is metabolized in the liver, ultimately becoming glucuronide and sulfate conjugates.[4] Its biological half-life is reported to be 9 hours when taken by mouth and 24 hours when given by intramuscular injection in the form of an aqueous suspension.[5][2] It is said to have a duration of action of one week or more via intramuscular injection.[4]

Chemistry

Stanozolol, also known as 17α-methyl-2'H-androst-2-eno[3,2-c]pyrazol-17β-ol, is a synthetic 17α-alkylated androstane steroid and a derivative of 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) with a methyl group at the C17α position and a pyrazole ring attached to the A ring of the steroid nucleus.[6]

Synthesis

Chemical syntheses of stanozolol have been published.[22]

Detection in body fluids

Stanozolol is subject to extensive hepatic biotransformation by a variety of enzymatic pathways. The primary metabolites are unique to stanozolol and are detectable in the urine for up to 10 days after a single 5–10 mg oral dose. Methods for detection in urine specimens usually involve gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.[23][24][25]

History

In 1962, Stanozolol was brought to market in the US by Winthrop under the tradename "Winstrol" and in Europe by Winthrop's partner, Bayer, under the name "Stromba".[26]

Also in 1962, the Kefauver Harris Amendment was passed, amending the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to require drug manufacturers to provide proof of the effectiveness of their drugs before approval.[27] The FDA implemented its Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) program to study and regulate drugs, including stanozolol, that had been introduced prior to the amendment. The DESI program was intended to classify all pre-1962 drugs that were already on the market as effective, ineffective, or needing further study.[28] The FDA enlisted the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences to evaluate publications on relevant drugs under the DESI program.[29]

In June 1970 the FDA announced its conclusions on the effectiveness of certain AAS, including stanozolol, based on the NAS/NRC reports made under DESI. The drugs were classified as probably effective as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of senile and postmenopausal osteoporosis but only as an adjunct, and in pituitary dwarfism (with a specific caveat for dwarfism, "until growth hormone is more available"), and as lacking substantial evidence of effectiveness for several other indications. Specifically, the FDA found a lack of efficacy for stanozolol as "an adjunct to promote body tissue-building processes and to reverse tissue-depleting processes in such conditions as malignant diseases and chronic nonmalignant diseases; debility in elderly patients, and other emaciating diseases; gastrointestinal disorders resulting in alterations of normal metabolism; use during pre-operative and postoperative periods in undernourished patients and poor-risk surgical cases due to traumatism; use in infants, children, and adolescents who do not reach an adequate weight; supportive treatment to help restore or maintain a favorable metabolic balance, as in postsurgical, postinfectious, and convalescent patients; of value in pre- operative patients who have lost tissue from a disease process or who have associated symptoms, such as anorexia; retention and utilization of calcium; surgical applications; gastrointestinal disease, malnourished adults, and chronic illness; pediatric nutritional problems; prostatic carcinoma; and endocrine deficiencies."[30] The FDA gave Sterling six months to stop marketing stanozolol for the indications for which there was no evidence for efficacy, and one year to submit further data for the two indications for which it found probable efficacy.[30]

In August and September 1970, Sterling submitted more data; the data was not sufficient but the FDA allowed the drug to continued to be marketed, since there was an unmet need for drugs for osteoporosis and pituitary dwarfism, but Sterling was required to submit more data.[31]

In 1980 the FDA removed the dwarfism indication from the label for stanozolol since human growth hormone drugs had come on the market, and mandated that the label for stanozolol and other steroids say: "As adjunctive therapy in senile and postmenopausal osteoporosis. AAS are without value as primary therapy but may be of value as adjunctive therapy. Equal or greater consideration should be given to diet, calcium balance, physiotherapy, and good general health promoting measures." and gave Sterling a timeline to submit further data for other indications it wanted for the drug.[32] Sterling submitted data to the FDA intended to support the effectiveness of Winstrol for postmenopausal osteoporosis and aplastic anemia in December, 1980 and August 1983 respectively. The FDA's Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee considered the data submitted for osteoporosis in two meetings held 1981 and the data for aplastic anemia in 1983.[31]

In April 1984, the FDA announced that the data was not sufficient, and withdrew the marketing authority for stanozolol for senile and postmenopausal osteoporosis and for raising hemoglobin levels in aplastic anemia.[31][33]

In 1988, Sterling was acquired by Eastman Kodak for $5.1 billion and in 1994 Kodak sold the drug business of Sterling to Sanofi for $1.675 billion.[34][35]

Sanofi had stanozolol manufactured in the US by Searle, which stopped making the drug in October 2002.[36] Even with no drug in production, Sanofi sold the stanozolol business to Ovation Pharmaceuticals in 2003, along with the two other drugs.[37] At that time, the drug had not been discontinued and was considered a treatment for hereditary angioedema.[37] In March 2009, Lundbeck purchased Ovation[38]

In 2010, Lundbeck withdrew stanozolol from the market in the US; as of 2014 no other company is marketing stanozolol as a pharmaceutical drug in the US but it can be obtained via a compounding pharmacy.[39][40][41][42]

Pfizer had marketed stanozolol as a veterinary drug; in 2013 Pfizer spun off its veterinary business to Zoetis[43] and in 2014 Pfizer transferred the authorizations to market injectable and tablet forms of stanozolol as a veterinary drug to Zoetis.[44][45]

It is used in veterinary medicine as an adjunct in the management of wasting diseases, to stimulate the formation of red blood cells, arouse appetite, and promote weight gain, but the evidence for these uses is weak. It is used as a performance-enhancing drug in race horses. Its side effects include weight gain, water retention, and difficulty eliminating nitrogen-based waste products and it is toxic to the liver, especially in cats. Because it may promote the growth of tumors, it is contraindicated in dogs with enlarged prostates.[46]:730–371

Stanozolol and other AAS were commonly used to treat hereditary angioedema attacks, until several drugs were brought to market specifically for treatment of that disease, the first in 2009: Cinryze, Berinert, ecallantide (Kalbitor), icatibant (Firazyr) and Ruconest.[41][42] Stanozolol is still used long-term to reduce the frequency of severity of attacks.[47]

Society and culture

Generic names

Stanozolol is the generic name of stanozolol in English, German, French, and Japanese and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCF, and JAN, while stanozololum is its name in Latin, stanozololo is its name in Italian and its DCIT, and estanozolol is its name in Spanish.[6][48][1] Androstanazole, androstanazol, stanazol, stanazolol, and estanazolol are unofficial synonyms of stanozolol.[6][1] It is also known by its former developmental code name WIN-14833.[6][1][48]

Brand names

Brand names under which stanozolol is or has been marketed include Anaysynth, Menabol, Neurabol Caps., Stanabolic (veterinary), Stanazol (veterinary), Stanol, Stanozolol, Stanztab, Stargate (veterinary), Stromba, Strombaject, Sungate (veterinary), Tevabolin, Winstrol, Winstrol Depot, and Winstrol-V (veterinary).[6][1]

The tradename Anabol should not be confused with Anabiol.

Legal status

In the United States, like other AAS, stanozolol is classified as a controlled substance under federal regulation; they were included as Schedule III controlled substances under the Anabolic Steroids Act, which was passed as part of the Crime Control Act of 1990.[49]:30 In New York, the state legislature classifies AAS under DEA Schedule III.

Doping in sports

Stanozolol and other synthetic steroids were first banned by the International Olympic Committee and the International Association of Athletics Federations in 1974, after methods to detect them had been developed.[50]:716 There are many known cases of doping in sports with stanozolol by professional athletes. Stanozolol is especially widely used by the athletes from post-Soviet countries. As of 2015, it is banned by World Anti-Doping Agency[51] and United States Anti-Doping Agency.[52]

Research

Stanozolol has been investigated in the treatment of a number of dermatological conditions including urticaria, hereditary angioedema, Raynaud's phenomenon, cryofibrinogenemia, and lipodermatosclerosis.[53]

References

- "Stanozolol - Drugs.com".

- Thieme D, Hemmersbach P (18 December 2009). Doping in Sports. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-3-540-79088-4.

The oral form is marketed for human use whereas an aqueous suspension for injection is used in the veterinary field.

- Maini AA, Maxwell-Scott H, Marks DJ (February 2014). "Severe alkalosis and hypokalemia with stanozolol misuse". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 32 (2): 196.e3–4. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.09.027. PMID 24521609.

This case is important as stanozolol misuse is relatively common, due to its high oral bioavailability and perceived safety profile compared with other parenteral AAS.

- Hsu WH (25 April 2013). Handbook of Veterinary Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 404–. ISBN 978-1-118-71416-4.

- Ruiz P, Strain EC (2011). Lowinson and Ruiz's Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 358–. ISBN 978-1-60547-277-5.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 961–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Llewellyn W (2011). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. pp. 726–737. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4.

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- "stanozolol (CHEBI:9249)". www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- "Anabolic Steroids Still an Issue in U.S. Horse Racing". The Horse. 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- "Win, Place, and Dope". Slate. 1 May 2009.

- Burnand K, Clemenson G, Morland M, Jarrett PE, Browse NL (January 1980). "Venous lipodermatosclerosis: treatment by fibrinolytic enhancement and elastic compression". British Medical Journal. 280 (6206): 7–11. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6206.7. PMC 1600523. PMID 6986945.

- McMullin GM, Watkin GT, Coleridge Smith PD, Scurr JH (April 1991). "Efficacy of fibrinolytic enhancement with stanozolol in the treatment of venous insufficiency". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 61 (4): 306–9. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00217.x. PMID 2018441.

- Sloane DE, Lee CW, Sheffer AL (September 2007). "Hereditary angioedema: Safety of long-term stanozolol therapy". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 120 (3): 654–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.037. PMID 17765757.

- Tingus SJ, Carlsen RC (April 1993). "Effect of continuous infusion of an anabolic steroid on murine skeletal muscle". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 25 (4): 485–94. PMID 8479303.

- "Winstrol side effects and instructions how to avoid them". Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Kicman AT (June 2008). "Pharmacology of anabolic steroids". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 502–21. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.165. PMC 2439524. PMID 18500378.

- Doods HN (1991). Receptor Data for Biological Experiments: A Guide to Drug Selectivity. Ellis Horwood. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-13-767450-3.

- Bilezikian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan GA (19 January 2002). Principles of Bone Biology, Two-Volume Set. Academic Press. pp. 1455–. ISBN 978-0-08-053960-7.

Androgenic compounds rendered resistant to gastrointestinal and liver metabolism by containing an alkyl group at the C17α position, such as stanozolol, are orally active.

- Herron A, Brennan TK (18 March 2015). The ASAM Essentials of Addiction Medicine. Wolters Kluwer Health. pp. 262–. ISBN 978-1-4963-1067-5.

Testosterone has low oral bioavailability with only about half of an oral dose available after hepatic first-pass metabolism. Some analogues of testosterone (e.g., methyltestosterone, fluoxymesterone, oxandrolone, and stanozolol) resist such metabolism, so they can be given orally in smaller doses.

- Saartok T, Dahlberg E, Gustafsson JA (June 1984). "Relative binding affinity of anabolic-androgenic steroids: comparison of the binding to the androgen receptors in skeletal muscle and in prostate, as well as to sex hormone-binding globulin". Endocrinology. 114 (6): 2100–6. doi:10.1210/endo-114-6-2100. PMID 6539197.

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. Elsevier. 22 October 2013. pp. 3067–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- Mateus-Avois L, Mangin P, Saugy M (February 2005). "Use of ion trap gas chromatography-multiple mass spectrometry for the detection and confirmation of 3'hydroxystanozolol at trace levels in urine for doping control". Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 816 (1–2): 193–201. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.11.033. PMID 15664350.

- Pozo OJ, Van Eenoo P, Deventer K, Lootens L, Grimalt S, Sancho JV, et al. (October 2009). "Detection and structural investigation of metabolites of stanozolol in human urine by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry". Steroids. 74 (10–11): 837–52. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2009.05.004. PMID 19464304. S2CID 36617387.

- Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1442–3.

- Levin J, Trafford JA, Bishop PM (1962). "Stanozolol, a new anabolic steroid". The Journal of New Drugs. 2: 50–5. PMID 14464563.

- "Promoting Safe and Effective Drugs for 100 Years". The Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- "FDA aims to remove unapproved drugs from market: Risk-based enforcement program focuses on removing potentially harmful products" (PDF). Pharmacy Today. United States Food and Drug Administration. August 2008.

- "The Drug Efficacy Study of the National Research Council's Division of Medical Sciences, 1966-1969". National Academies of Sciences archives.

- "Food and Drug Administration Notice.DESI 7630. Certain Anabolic Steroids. Drugs for Human Use: Drug Efficacy Study Implementation". Federal Register. 35 (122): 10327–28. 24 June 1970.

- Food and Drug Administration Notice. Docket No 80N-0276; DESI 7630. Winstrol Tablets; Drugs for Human Use; Drug Efficacy Study Implementation, Revocation of Exemption; Followup Notice and Opportunity for Hearing on Proposal to Withdraw Approval of New Drug Federal Register, April 23, 1984. page 17094-99

- Food and Drug Administration Notice. Docket No 80N-0276; Drugs for Human Use; Drug Efficacy Study Implementation; Conditions for Continued Marketing of Anabolic Steroids for Treatment Federal Register Vol 45 No. 213. October 31 1980. pages 72291-93

- The Pink Sheet 30 April 1984 Sterling Winstrol (Stanozolol) NDA Withdrawal Process Beginning, FDA

- Collins JC, Gwilt JR (2000). "The Life Cycle of Sterling Drug, Inc" (PDF). Bull. Hist. Chem. 25 (1).

- "Kodak to Sell Drug Unit for $1.68 Billion". Los Angeles Times. June 24, 1994. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- "Products". Ovation Pharmaceuticals. Archived from the original on 2004-01-10.

- "Press release: Ovation Pharmaceuticals Acquires Mebaral(R), Chemet(R), and Winstrol(R) From Sanofi-Synthelabo Inc". PRnewswire. 7 August 2003.

- "Press Release: GTCR Completes the Sale of Ovation Pharmaceuticals to Lundbeck". Reuters. 19 March 2009.

- "Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. et al.; Withdrawal of Approval of 27 New Drug Applications and 58 Abbreviated New Drug Applications". 21 July 2010.

- FDA Drugs@FDA: Stanozolol

- The US Hereditary Angioedema Association Treatments

- Craig TJ, Kalra N (30 July 2012). "Contemporary Issues in Prophylactic Therapy of Hereditary Angioedema". MedScape Education.

- Zoetis. 24 June 2013 Zoetis Press Release: Zoetis Becomes Fully Independent With Acceptance of Pfizer Shares Tendered in Exchange Offer

- "Implantation or Injectable Dosage Form New Animal Drugs; Change of Sponsor". Federal Register. 20 May 2014.

- "Oral Dosage Form New Animal Drugs; Change of Sponsor". A Rule by the Food and Drug Administration. Federal Register. 25 March 2014.

- Riviere JE, Papich MG (2013). Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-68590-7.

- Delves PJ (March 2014). "Hereditary and Acquired Angioedema". Merck Manual.

- Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 261–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- Karch SB (2007). Pathology, Toxicogenetics, and Criminalistics of Drug Abuse. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-5456-9.

- Shänzer W (2004). "Abuse of Androgens and Detection of Illiegal Use Chapter 24". In Nieschlag E, Behr HM (eds.). Testosterone: Action, Deficiency, Substitution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45221-2.

- Ozcagli, Eren; Kara, Mehtap; Kotil, Tugba; Fragkiadaki, Persefoni; Tzatzarakis, Manolis N.; Tsitsimpikou, Christina; Stivaktakis, Polychronis D.; Tsoukalas, Dimitrios; Spandidos, Demetrios A.; Tsatsakis, Aristides M.; Alpertunga, Buket (July 2018). "Stanozolol administration combined with exercise leads to decreased telomerase activity possibly associated with liver aging". International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 42 (1): 405–413. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2018.3644. ISSN 1107-3756. PMC 5979936. PMID 29717770.

- "What is Stanozolol? Education, Science, Spirit of Sport / April 29, 2015". www.usada.org. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Helfman T, Falanga V (August 1995). "Stanozolol as a novel therapeutic agent in dermatology". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 33 (2 Pt 1): 254–8. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90244-9. PMID 7622653.