Languages of Bhutan

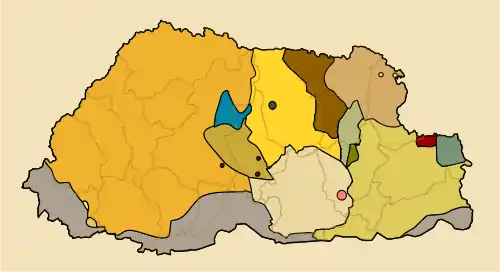

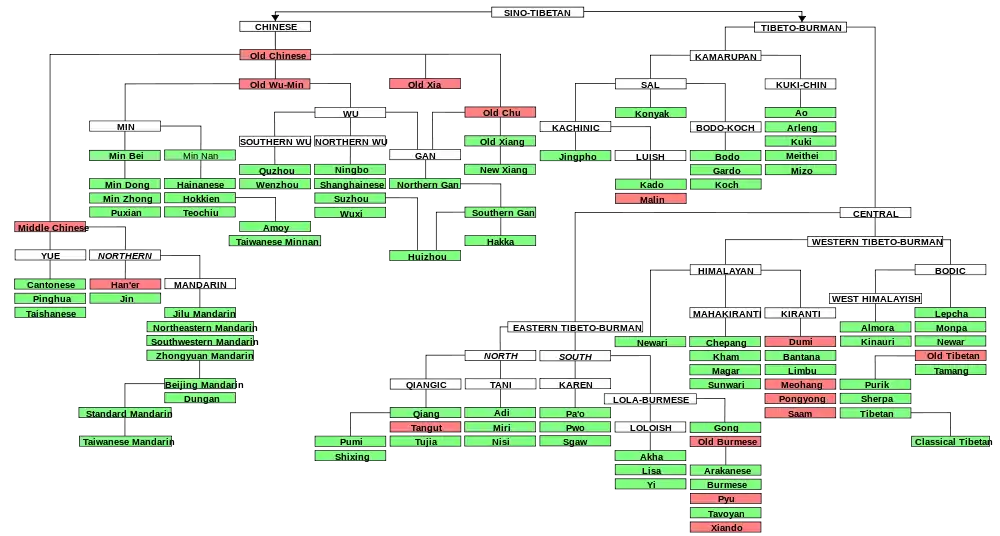

There are two dozen languages of Bhutan, all members of the Tibeto-Burman language family except for Nepali, which is an Indo-Aryan language, and Bhutanese Sign Language.[1] Dzongkha, the national language, is the only language with a native literary tradition in Bhutan, though Lepcha and Nepali are literary languages in other countries.[2] Other non-Bhutanese minority languages are also spoken along Bhutan's borders and among the primarily Nepali-speaking Lhotshampa community in South and East Bhutan.

Dzongkha and other Tibetan languages

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bhutan |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Sport |

The Central Bodish languages are a group of related Tibetic languages descended from Old Tibetan (Chöke). Most Bhutanese varieties of Central Bodish languages are of the Southern subgroup. At least six of the nineteen languages and dialects of Bhutan are Central Bodish languages.

Dzongkha is a Central Bodish language[2] with approximately 160,000 native speakers as of 2006.[3] It is the dominant language in Western Bhutan, where most native speakers are found. It was declared the national language of Bhutan in 1971.[4] Dzongkha study is mandatory in schools, and the majority of the population speaks it as a second language. It is the predominant language of government and education.[2] The Chocangaca language, a "sister language" to Dzongkha, is spoken in the Kurichu Valley of Eastern Bhutan by about 20,000 people.[2]

The Lakha (8,000 speakers) and Brokkat languages (300 speakers) in Central Bhutan, as well as the Brokpa language (5,000 speakers) in far Eastern Bhutan, are also grouped by Van Driem (1993) into Central Bodish. These languages are remnants of what were originally pastoral yakherd communities.[2]

The Laya dialect, closely related to Dzongkha, is spoken near the northwestern border with Tibet by some 1,100 Layaps. Layaps are an indigenous nomadic and semi-nomadic people who traditionally herd yaks and dzos.[5][6][7] Dzongkha speakers enjoy a limited mutual intelligibility, mostly in basic vocabulary and grammar.[8]

Khams Tibetan is spoken by about 1,000 people in two enclaves in Eastern Bhutan, also the descendants of pastoral yakherding communities.[2] Although it also is a by all accounts a Tibetic language, its exact subgrouping is uncertain.

East Bodish languages

Eight of the languages of Bhutan are East Bodish languages, not members of the closely related Tibetic group but still descended from Old Tibetan or a close kin.[9]

The Bumthang language, or Bumthangkha, is the dominant language in Central Bhutan. It has approximately 30,000 speakers. The Kheng and Kurtöp languages are closely related to Bumthang. They have 40,000 and 10,000 speakers, respectively.

The Dzala language, or Dzalakha, has about 15,000 speakers. The Nyen language, also called Henkha or Mangdebikha, and the 'Ole language (also called the "Black Mountain language" or "Mönkha") are spoken in the Black Mountains of Central Bhutan by about 10,000 and 1,000 speakers, respectively. Van Driem (1993) describes 'Ole as the remnant of the primordial population of the Black Mountains before the southward expansion of the ancient East Bodish tribes.[2]

The Dakpa (Dakpakha) and Chali (Chalikha) languages are each spoken by about 1,000 people in Eastern Bhutan.[2]

Other Tibeto-Burman languages

Other Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken in Bhutan. These languages are more distantly related to the Bodish languages, and are not necessarily members of any common subgroup.

The Tshangla language, a subfamily of its own of the Bodish languages, has approximately 138,000 speakers. It is the mother tongue of the Sharchops. It is the dominant language in Eastern Bhutan and was formerly spoken as a lingua franca in the region.[2]

The Gongduk language is an endangered language that has approximately 1,000 speakers in isolated villages along the Kuri Chhu river in Eastern Bhutan. It appears to be the sole representative of a unique branch of the Tibeto-Burman language family,[11] and retains the complex verbal agreement system of Proto-Tibeto-Burman.[12] Van Driem (1993) describes its speakers as a remnant of the ancient population of Central Bhutan before the southward expansion of the East Bodish tribes.[2]

The Lepcha language has approximately 2,000 ethnic Lepcha people in Bhutan.[2] It has its own highly stylized Lepcha script.

The Lhokpu language has approximately 2,500 speakers. It is one of the autochthonous languages of Bhutan and is yet unclassified within Tibeto-Burmese. Van Driem (1993) describes it as the remnant of "the primordial population of Western Bhutan," and comments that Lhokpu or a close relative appears to have been the substrate language for Dzongkha, explaining the various ways in which Dzongkha diverged from Tibetan.[2] It is spoken by the Lhop people.

Indo-Aryan

The Nepali language is the only Indo-Aryan language spoken by native Bhutanese. Inside Bhutan, it is spoken primarily in the south by the approximately 265,000 resident Lhotshampa as of 2006.[13] While the Lhotshampa are generally regarded as Nepali speakers, the Lhotshampa include many smaller non-Indo-Aryan groups such as the Tamang[14] and Gurung[14] in Southern Bhutan, and the Kiranti groups (including the Rai and Limbu peoples) found in Eastern Bhutan. Among these minorities are speakers of Chamling, Limbu, and Nepal Bhasa.

Border languages

The Sikkimese and Groma languages, both Tibetan languages, are spoken along the Sikkim-Bhutan and Tibet-Bhutan borders in Western Bhutan.

The Toto language is generally classified as belonging to the sub-Himalayan branch of the Tibeto-Burman family.[15] It is spoken by the isolated Toto tribe in Totopara and along the West Bengal-Bhutan border in South Bhutan. The total Toto population was about 1,300 people in 2006,[15] mainly on the Indian side of the border.

References

- Van Driem, George L.; K. Tshering (1998). Dzongkha. Languages of the Greater Himalayan Region. 1. Research CNWS, School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies. ISBN 90-5789-002-X.

- van Driem, George L. (1993). "Language Policy in Bhutan". London: SOAS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-11. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- "Dzongkha". Ethnologue Online. Dallas: SIL International. 2006. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- "Language romanization" (PDF). www.himalayanlanguages.org. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- Wangdi, Kencho (2003-11-04). "Laya: Not Quite a Hidden Land". Kuensel online. Archived from the original on 2003-12-07. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). Layakha. Ethnologue: Languages of the World (16 (online) ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- van Driem, George; Tshering, Karma (1998). Dzongkha. Languages of the Greater Himalayan Region. 1. Research CNWS, School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies. p. 1. ISBN 90-5789-002-X. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

- "Tribe – Layap". BBC online. 2006-05-01. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- van Driem, page 18

- Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (ed.s) (2003). Sino-Tibetan Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1129-5.

- Himalayan Languages Project. "Gongduk". Himalayan Languages Project. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- "Gongduk: A language of Bhutan". Ethnologue Online. Dallas: SIL International. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- Ethnologue 16

- Repucci, Sarah; Walker, Christopher (2005). Countries at the Crossroads: A Survey of Democratic Governance. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 92. ISBN 0-7425-4972-0.

- Kolig, Erich; Angeles, Vivienne SM.; Wong, Sam (ed.s) (2009). "Socio-Economic Crisis and Its Consequences". Identity in Crossroad Civilisations: Ethnicity, Nationalism and Globalism in Asia. Amsterdam: ICAS/Amsterdam University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-90-8964-127-4.

External links

- Dzongkha Development Commission - Official language body of Bhutan