Navajo Nation

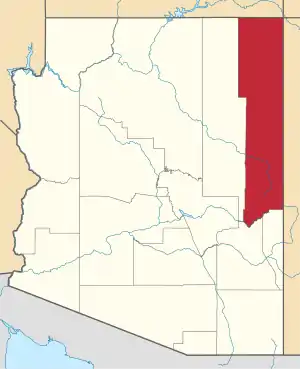

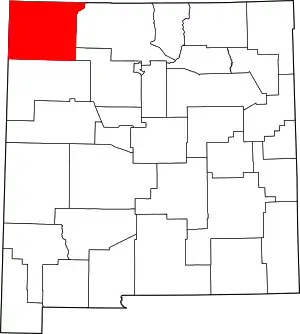

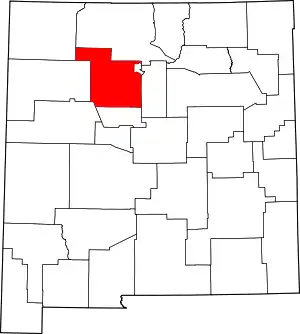

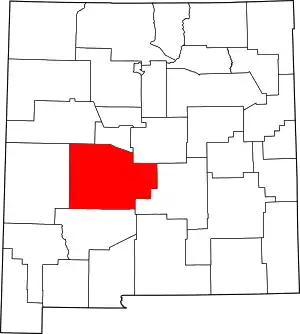

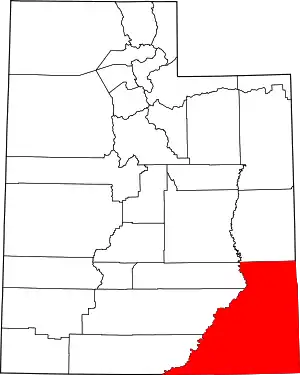

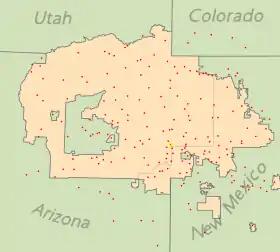

The Navajo Nation (Navajo: Naabeehó Bináhásdzo) is a Native American[2] indigenous tribe covering about 17,544,500 acres (71,000 km2; 27,413 sq mi), occupying portions of northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah, and northwestern New Mexico in the United States. This is the largest land area retained by an indigenous tribe in the United States, with a population of 173,667 as of 2010.

Navajo Nation

Naabeehó Bináhásdzo | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

| Anthem: ("Dah Naatʼaʼí Sǫʼ bił Sinil" and "Shí naashá" used for some occasions) | |

Location of the Navajo Nation. Checkerboard-area in lighter shade (see text) | |

| Established | June 1, 1868 (Treaty) |

| Expansions | 1878–2016 |

| Chapter system | 1922 |

| Tribal Council | 1923 |

| Capital | Window Rock (Tségháhoodzání) |

| Subdivisions | |

| Government | |

| • Body | Navajo Nation Council |

| • President | Jonathan Nez (D) |

| • Vice President | Myron Lizer (R) |

| • Speaker of the Navajo Council | Seth Damon (D) |

| • Chief Justice | JoAnn Jayne |

| Area | |

| • Total | 71,000 km2 (27,413 sq mi) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 173,667 |

| • Density | 2.4/km2 (6.3/sq mi) |

| 166,826 Navajo/Nat. Am. 3,249 White 3,594 other, incl. multiple | |

| Time zone | MST/MDT |

| Website | www.navajo-nsn.gov |

By area, the Navajo Nation is larger than ten U.S. states – West Virginia, Maryland, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware and Rhode Island – and is less than one percent shy of being equal to the combined area of the last five (New Hampshire through Rhode Island).[3]

The original indigenous tribe has expanded several times since the 19th century.

Terminology

In English, the official name for the area was "Navajo Indian Reservation", as outlined in Article II of the 1868 Treaty of Bosque Redondo. On April 15, 1969, the tribe changed its official name to the Navajo Nation, which is also displayed on the seal. In 1994, the Tribal Council rejected a proposal to change the official designation from "Navajo" to "Diné." It was remarked that the name Diné represented the time of suffering before the Long Walk, and that Navajo is the appropriate designation for the future.[5]

In Navajo, the geographic entity with its legally defined borders is known as "Naabeehó Bináhásdzo". This contrasts with "Diné Bikéyah" and "Naabeehó Bikéyah" for the general idea of "Navajoland".[6] Neither of these terms should be confused with "Dinétah," the term used for the traditional homeland of the Navajo, which is situated in the area among the four sacred Navajo mountains of Dookʼoʼoosłííd (San Francisco Peaks), Dibé Ntsaa (Hesperus Mountain), Sisnaajiní (Blanca Peak), and Tsoodził (Mount Taylor).

History

The Navajo people's tradition of governance is rooted in their clans and oral history.[7] The clan system of the Diné is integral to their society, as the rules of behavior found within the system extend to the manner of refined culture that the Navajo people call "to walk in Beauty".[8] The philosophy and clan system extend from before the Spanish colonial occupation of Dinetah, through to the July 25, 1868, Congressional ratification of the Navajo Treaty with President Andrew Johnson, signed by Barboncito, Armijo, and other chiefs and headmen present at Bosque Redondo.

The Navajo people have continued to transform their conceptual understandings of government since it joined the United States by the Treaty of 1868. Social, cultural and political academics continue to debate the nature of the modern Navajo governance and how it has evolved to include the systems and economies of the "western world".[9]

Reservation and expansion

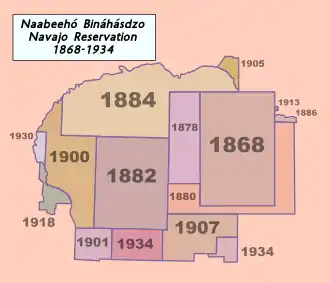

In the mid-19th century, most Navajo were forced from their lands by the US government, and were marched on the Long Walk to imprisonment in Bosque Redondo.[10] The Treaty of 1868 established the "Navajo Indian Reservation" and the Navajos left Bosque Redondo. The borders were defined as the 37th parallel in the north; the southern border as a line running through Fort Defiance; the eastern border as a line running through Fort Lyon; and in the west as longitude 109°30′.[11]:68

As drafted in 1868, the boundaries were defined as:

the following district of country, to wit: bounded on the north by the 37th degree of north latitude, south by an east and west line passing through the site of old Fort Defiance, in Canon Bonito, east by the parallel of longitude which, if prolonged south, would pass through old Fort Lyon, or the Ojo-de-oso, Bear Spring, and west by a parallel of longitude about 109' 30" west of Greenwich, provided it embraces the outlet of the Canon-de-Chilly [Canyon de Chelly], which canyon is to be all included in this reservation, shall be, and the same hereby, set apart for the use and occupation of the Navajo tribe of Indians, and for such other friendly tribes or individual Indians as from time to time they may be willing, with the consent of the United States, to admit among them; and the United States agrees that no persons except those herein so authorized to do, and except such officers, soldiers agents, and employees of the Government, or of the Indians, as may be authorized to enter upon Indian reservations in discharge of duties imposed by law, or the orders of the President, shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in, the territory described in this article.[12]

Though the treaty had provided for one hundred miles by one hundred miles in the New Mexico Territory, the size of the territory was 3,328,302 acres (13,470 km2; 5,200 sq mi)[11]—slightly more than half. This initial piece of land is represented in the design of the Navajo Nation's flag by a dark-brown rectangle.[13]

As no physical boundaries or signposts were set in place, many Navajo ignored these formal boundaries and returned to where they had been living prior to captivity.[11] A significant number of Navajo had never lived in the Hwéeldi (near Fort Sumner). They remained or moved to near the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers, on Naatsisʼáán (Navajo Mountain) and some with Apache bands.[10]

The first expansion of the territory occurred on October 28, 1878, when President Rutherford Hayes signed an executive order pushing the reservation boundary 20 miles to the west.[11] Further additions followed throughout the late 19th and early 20th century (see map). Most of these additions were achieved through executive orders, some of which were confirmed by acts of Congress; for example, President Theodore Roosevelt's executive order to add the region around Aneth, Utah in 1905 was confirmed by Congress in 1933.[14]

The eastern border was shaped primarily as a result of allotments of land to individual Navajo households under the Dawes Act of 1887. This experiment was designed to assimilate Native Americans to the majority culture. The federal government proposed to divide communal lands into plots assignable to heads of household – tribal members – for their subsistence farming, in the pattern of small family farms common among European Americans. The land allocated to Navajos was initially not considered as part of the reservation. Further, the government determined that land "left over" after all members had received allotments was to be considered "surplus" and available for sale to non-Native Americans. The allotment program continued until 1934. Today, this patchwork of reservation and non-reservation land is called "the checkerboard" area.

In the southeastern area of the reservation, the Navajo Nation has purchased some ranches, which it calls its Nahata Dzil or New Lands. They are leased to Navajo individuals, livestock and grazing associations, and livestock companies.

In 1996, Elouise Cobell (Blackfeet) filed a class action suit against the federal government on behalf of an estimated 250,000–500,000 plaintiffs, Native Americans whose trust accounts did not reflect an accurate accounting of monies owed them under leases or fees on trust lands. The settlement of Cobell v. Salazar in 2009 included a provision for a nearly $2 billion fund for the government to buy fractionated interests and restore land to tribal reservations. Individuals could sell their fractionated land interests on a voluntary basis, at market rates, through this program if their tribe participated.

Through March 2017, under the Tribal Nations Buy-Back Program, individual Navajo members received $104 million for purchase of their interests in land; 155,503 acres were returned to the Navajo Nation for its territory by the Department of Interior under this program.[16] The program is intended to help tribes restore the land bases of their reservations. Almost 11,000 Navajo citizens were paid for their interests under this program. The tribe intends to use the consolidated lands to "streamline infrastructure projects," such as running power lines.

Clan governance

In the traditional Navajo culture, local leadership was organized around clans, which are matrilineal kinship groups. Children are considered born into the mother's family and gain their social status from her.

The clan leadership have served as a de facto government on the local level of the Navajo Nation.

Rejection of Indian Reorganization Act

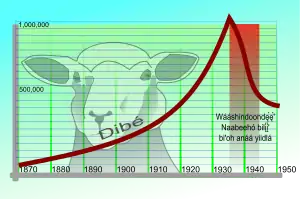

In 1933 during the Great Depression, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) attempted to mitigate environmental damage due to over-grazing on reservations. This created an environment of misunderstanding, as its representatives did not consult sufficiently with the Navajo. BIA Superintendent John Collier's attempt to reduce livestock herd size affected responses to his other efforts to improve conditions for Native Americans, as the herds were central to Navajo culture, and were a source of prestige.[17]

Also during this period, under the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, the federal government was encouraging tribes to revive their governments according to constitutional models shaped after the United States. Because of the outrage and discontent about the herd issues, the Navajo voters did not trust the language of the proposed initial constitution outlined in the legislation. This contributed to their rejection of the first version of a proposed tribal constitution.

In the various attempts since, members found the process to be too cumbersome and a potential threat to tribal self-determination, as the constitution was supposed to be reviewed and approved by BIA. The earliest efforts were rejected primarily because segments of the tribe did not find enough freedom in the proposed forms of government. In 1935 they feared that the proposed government would hinder development and recovery of their livestock industries; in 1953 they worried about restrictions on development of mineral resources.

They continued a government based on traditional models, with headmen chosen by clan groups.

Navajo Nation and federal government jurisdictions

The United States still asserts plenary power and thus requires the territory of the Navajo Nation to submit all proposed laws to the United States Secretary of the Interior for Secretarial Review, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

The US Supreme Court in United States v. Kagama (1889) affirmed that Congress has plenary power over all Indian tribes within United States borders, saying that "The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful ... is necessary to their protection as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell".[18] It noted that the tribes did not owe allegiance to the states within which their reservations were located.[19]

Most conflicts and controversies between the federal government of the United States and the Nation are settled by negotiations outlined in political agreements. The Navajo Nation Code comprises the rules and laws of the Navajo Nation as currently codified in the latest edition.

Lands within the exterior boundaries of the Navajo Nation are composed of Public, Tribal Trust, Tribal Fee, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Private, State, and BIA Indian Allotment Lands. On the Arizona and Utah portions of the Navajo Nation, there are a few private and BIA Indian Allotments in comparison to New Mexico's portion which consists of a checkerboard pattern of all the aforementioned lands. The Eastern Agency, as it is referred to, consists of primarily Tribal Fee, BIA Indian Allotments, and BLM Lands. Although there are more Tribal Fee Lands in New Mexico, the Navajo Nation government intends to convert most or all Tribal Fee Lands to Tribal Trust.

Government

The Title II Amendment of 1989 established the Navajo Nation government as a three-part system (changes to the judicial branch had already begun in 1958). Two branches are independent of the council (where all government decision making was centralized before the change).

The president and vice-president are elected every four years. The Executive nominates judges of the District Courts, and the Supreme Court.[20] The nation consists of several divisions, departments, offices, and programs as established by law.[21]

Constitution

In 2006, a committee for a "Navajo constitution" began advocating for a Navajo constitutional convention. The committee's goal was to have representation from every chapter on the Navajo Nation represented at a constitutional convention. The committee proposed the convention be held in the traditional naachid/modern chapter house format, where every member of the nation wishing to participate may do so through their home chapters. The committee was formed by former Navajo leaders: Kelsey Begaye, Peterson Zah, Peter MacDonald, writer/social activist Ivan Gamble, and other local political activists.[22]

Judiciary branch

Prior to Long Walk of the Navajo, judicial powers were exercised by peace chiefs (Hózhǫ́ǫ́jí Naatʼááh) in a mediation-style process.[23] While the people were held at Bosque Redondo, the U.S. Army handled severe crimes while lesser crimes and disputes remained in the purview of the villages' chiefs. After the Navajo return from Bosque Redondo in 1868, listed offenses were handled by the Indian Agent of the Bureau of Indian Affairs with support of the U.S. Army while lesser disputes remained under Navajo control.

In 1892, BIA Agent David L. Shipley established the Navajo Court of Indian Offenses and appointed judges.[24] Previously, judicial authority was exercised by the Indian Agent.[24]

In 1950, the Navajo Tribal Council decided that judges should be elected. By the time of the judicial reorganization of 1958, the council had determined that, due to problems with delayed decisions and partisan politics, appointment was a better method of selecting judges.[25]

The president makes appointments subject to confirmation by the Navajo Nation Council; however, the president is limited to the list of names vetted by the Judiciary Committee of the council.[26]

The current judicial system for the Navajo Nation was created by the Navajo Tribal Council on 16 October 1958. It established a separate branch of government, the "Judicial Branch of the Navajo Nation Government", which became effective 1 April 1959.[27] The Navajo Court of Indian Offenses was eliminated; the sitting judges became judges in the new system. The resolution established "Trial Courts of the Navajo Tribe" and the "Navajo Tribal Court of Appeals", which was the highest court and the only appellate court.

In 1978, the Navajo Tribal Council established a "Supreme Judicial Council", a political body rather than a court. On a discretionary basis, it could hear appeals from the Navajo Tribal Court of Appeals.[28] Subsequently, the Supreme Judicial Council was criticized for bringing politics directly into the judicial system and undermining "impartiality, fairness and equal protection."[29]

In December 1985, the Navajo Tribal Council passed the Judicial Reform Act of 1985, which eliminated the Supreme Judicial Council. It redenominated the "Navajo Tribal Court of Appeals" as the "Navajo Nation Supreme Court", and redenominated the "Trial Courts of the Navajo Tribe" as "District Courts of the Navajo Nation".[30] Navajo courts are governed by Title 7, "Courts and Procedures", of the Navajo Tribal Code.[30]

From 1988 to 2006, there were seven judicial districts and two satellite courts. As of 2010, there are ten judicial districts, centered respectively in Alamo (Alamo/Tó'hajiilee), Aneth, Chinle, Crownpoint, Dilkon, Kayenta, Ramah, Shiprock, Tuba City and Window Rock.[31] All of the districts also have family courts, which have jurisdiction over domestic relations, civil relief in domestic violence, child custody and protection, name changes, quiet title and probate. As of 2010, there were 17 trial judges presiding in the Navajo district and family courts.[32]

Executive branch

The Navajo Nation Presidency, in its current form, was created on December 15, 1989, after directives from the federal government guided the Tribal Council to establish the current judicial, legislative, and executive model. This was a departure from the system of "Council and Chairmanship" from the previous government body.

Conceptual additions were added to the language of Navajo Nation Code Title II, and the acts expanded the new government on April 1, 1990. There are several qualifications for the position of president, including fluency in the Navajo language. (This has seldom been enforced and in 2015, the council changed the law to repeal this requirement.) Term limits allow only two consecutive terms.[33]

Legislative branch

The Navajo Nation Council, formerly the Navajo Tribal Council, is the legislative branch of the Navajo Nation. As of 2010, the Navajo Nation Council consists of 24 delegates representing the 110 chapters, elected every four years by registered Navajo voters. Prior to the November 2010 election, the Navajo Nation Council consisted of 88 representatives. The Navajo voted for the change in an effort to have a more efficient government and to curb tribal government corruption associated with council members who established secure seats.[34]

Chapters

In 1927, agents of the U.S. federal government initiated a new form of local government entities called Chapters, modeled after governments such as counties or townships. Each Chapter elected officers and followed parliamentary procedures.

By 1933, more than 100 chapters operated across the territory. The chapters served as liaisons between the Navajo and the federal government, and also acted as precincts for the elections of tribal council delegates. They served as forums for local tribal leaders. But, the chapters had no authority within the structure of the Navajo Nation government.[35]

In 1998, the Navajo Tribal Council passed the "Local Governance Act," which expanded the political roles of the existing 110 chapters. It authorized them to make decisions on behalf of the chapter members and take over certain roles previously delegated to the council and executive branches. This included entering into intergovernmental agreements with federal, state and tribal entities, subject to approval by the Intergovernmental Relations Committee of the council.

Agencies and chapters

The Navajo Nation is divided into five agencies across parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, with the seat of government located at the Navajo Governmental Campus at Window Rock/Tségháhoodzání. These agencies are similar to county entities and reflect the five Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agencies created in the early years of the Navajo Nation. The five agencies within the Navajo Nation are the Chinle Agency in Chinle, Arizona; Eastern Navajo Agency in Crownpoint, New Mexico; Western Navajo Agency in Tuba City, Arizona; Fort Defiance Agency in Fort Defiance, Arizona; and Shiprock Agency in Shiprock, New Mexico. The BIA agencies provide various technical services under direction of the BIA's Navajo Area Office at Gallup, New Mexico.

Agencies are further divided into chapters as the smallest political unit, similar to municipalities. The Navajo capital city of Window Rock is located in the Chapter of St. Michaels, Arizona.

The Navajo Nation also has executive offices in the US capital of Washington, DC for lobbying services and congressional relations.

Law enforcement

The Navajo law enforcement consists of roughly 300 tribal police officers with only 3 non-native officers.

Certain classes of crimes, such as capital cases, are prosecuted and adjudicated in Federal courts. However, the Navajo Nation operates its own divisions of law enforcement via the Navajo Division of Public Safety, commonly referred to as the Navajo Nation Police (formerly Navajo Tribal Police). Law enforcement functions are also delegated to the Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife: Wildlife Law Enforcement and Animal Control Sections; Navajo Nation Forestry Law Enforcement Officers; and the Navajo Nation EPA Criminal Enforcement Section; and Navajo Nation Resource Enforcement (Navajo Rangers).

Other local, state and federal law enforcement agencies routinely work on the Navajo Nation, including the BIA Police, National Park Service U.S. Park Rangers, U.S. Forest Service Law Enforcement and Investigations, Bureau of Land Management Law Enforcement, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), US Marshals, and Federal Bureau of Investigation; and other Native American units: the Ute Mountain Agency, and Hopi Agency; and Arizona Highway Patrol, Utah Highway Patrol, New Mexico Department of Public Safety (State Police and Highway Patrol), Apache County Sheriff's Office, Navajo County Sheriff's Office, McKinley County Sheriff's Office.

Other agencies

- Transportation

- Health

- Education

Regional Commissions

In addition, regional government functions are carried out by the "District Grazing Committees" and "Off-Reservation Land Boards", "Major Irrigation Projects Farm Boards", and "Agency Councils".[36]

Notable Navajo politicians

- Henry Chee Dodge, first chairman of Navajo Tribal Council (1922–1928, 1942–1946)

- Tom B. Becenti, tribal judge and chapter official from Eastern Navajo Agency. WWII veteran. He is known to have helped develop the Navajo Tribal Court System while preserving traditional Navajo Fundamental Law.[37]

- Peter MacDonald, Navajo Tribal chairman convicted for cause (1971–1983, 1987–1989)

- Jacob (JC) Morgan, first chairman elected by the tribe, serving 1938–1942

- Lilakai Julian Neil, first woman elected to Navajo Tribal Council, serving 1946–1951

- John Pinto, New Mexico state senator (1977-2019), code talker, teacher and National Education Association organizer.[38]

- Amos Frank Singer, early Council delegate from Kaibito and designer of Navajo Seal.

- Joe Shirley Jr., oversaw the reduction in seats on the Navajo Council.

- Annie Dodge Wauneka, Navajo Tribal Councilwoman and philanthropist (1951–1978)

- Peterson Zah, Chairman and first president of the Navajo Nation (1983–1987, 1991–1995)

2014 Navajo Presidential Election

On August 25, 2014, the Navajo Nation held primary elections for the Office of President.[39] Joe Shirley Jr. and Chris Deschene had the two highest vote counts. In the weeks following, two other primary candidates sued in tribal court, invoking a never-used 1990s law to require assessment of the candidates' skills in the Navajo Language.[40]

On October 23, 2014,[41] the Office of Hearings and Appeals of the tribe held the first hearing on the complaint filed against Deschene. The meeting was presided by chief hearing officer Richie Nez.[42] The court body ruled in favor of Dale Tsosie[43] and Hank Whitethorne, the former primary candidates, and issued a default ruling against Deschene, who had refused to participate. Later that day, the Navajo Supreme Court, in a special session on the matter, enforced the ruling from the lower Court body and ordered that the Navajo government remove Deschene from the presidential ballot because of his lack of Navajo language skills.[44]

The High Court ruled that the presidential election scheduled for November 4 (12 days later), would be postponed, and ordered that it be held by the end of January 2015. Chief Justice Herb Yazzie[45] and Associate Justice Eleanor Shirley ruled for the 2–1 majority; Justice Irene Black wrote in her dissent that the technicality must be sent back to the lower court for correction there. The decision did not outline who would act as executive at the end of the current president's term (January 2015). In the early hours of October 24, the Navajo Council passed legislative Bill 0298-14[46] amending the Navajo Nation Code. The legislation dissolved the language requirement of the qualifications sections for president. The legislation allowed for Chris Deschene's participation.[47]

The following Monday, the Navajo Board of Election Supervisors (NBES) met but took no action to implement the court directives. Counsel for NBES motioned the High Court for further instruction. The next day, the Navajo Nation Election Board commissioner, Wallace Charley, (he was joined later by Kimmeth Yazzie, Navajo Election Administration) announced that Deschene's name would remain on the ballot.[48] Though he vowed to continue, Deschene bowed out of the race on October 30.[49] On October 29, Ben Shelly vetoed the bill repealing the language requirement.[50] The Navajo General Election was held. The unofficial tally found Joe Shirley Jr. with the majority.

The Navajo Council scheduled a primary and general election for June and August 2015.[51] On Monday, January 5, 2015, President Shelly vetoed the language fluency bill.[52] On January 7, five assistant attorneys-general filed petition with the Navajo Nation Supreme Court for clarification on the question of the presidential vacancy issue. Through a controversial agreement and resolution, the Court and the Council appointed Ben Shelly to act as interim President.[53]

In the special election, businessman Russell Begaye was elected as president and Jonathan Nez as vice-president. In May 2015, they were sworn in. Begaye supports encouraging native language use among the Navajo, who have the most members speaking a native language of nearly any tribe. Approximately half of its 340,000 members speak Navajo. He came to office supporting the Grand Canyon Escalade, a proposed project to increase tourism at the canyon, as well as initiatives to develop a rail port to export crops and coal from the reservation and to pursue clean coal technology.[54]

Infrastructure

The Navajo Tribal Utility Authority provides utility services for houses. By 2019 there was a campaign to electrify remaining houses without electricity. As of 2019 about 15,000 houses, with 60,000 residents, did not have electricity; at that time the authority electrified, on an annual a basis, 400-450 houses.[55]

International cooperation

In December 2012, Ben Shelly led a delegation of Navajos overseas to Israel, where they toured the country as representatives for the Navajo people. In April 2013, Shelly's aide, Deswood Tome, led a delegation of Israeli agricultural specialists on a tour of resources on the Navajo Nation. The visit was criticized by some indigenous people who view Palestinian plight as similar to their own.[56]

Geography

The land area of the Navajo Nation is over 27,000 square miles (70,000 km2),[58] making it the largest Indian reservation in the United States; it is approximately 8,000 km2 larger than the state of West Virginia.

Adjacent to or near the Navajo Nation are the Southern Ute of Colorado, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe of Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico, both along the northern borders; the Jicarilla Apache Tribe to the east; the Zuni and White Mountain Apache to the south, and the Hualapai Bands in the west. The Navajo Nation's territory fully surrounds the Hopi Indian Reservation.[58] In the 1980s, a conflict over shared lands peaked when the Department of the Interior attempted to relocate Navajo residents living in what is still referred to as the Navajo–Hopi Joint Use Area. The litigious and social conflict between the two tribes and neighboring communities ended with "The Bennett Freeze" Agreement and was completed in July 2009 by President Barack Obama. The agreement lessened the contentious land disagreement with a 75-year lease to Navajos with claims dating to before the US occupation.

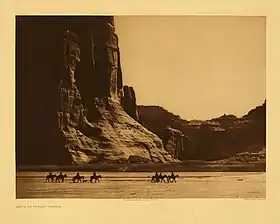

Situated on the Navajo Nation are Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Monument Valley, Rainbow Bridge National Monument, the Shiprock monadnock, and the eastern portion of the Grand Canyon. Navajo Territory in New Mexico is popularly referred as the "Checkerboard" area since the Federal Government's attempt to diversify lands with non-native lands. Thus these Navajo lands are intermingled with fee lands, owned by both Navajos and non-Navajos, and federal and state lands under various jurisdictions.[60][58] Three large non-contiguous sections located in New Mexico are also under Navajo jurisdiction and are the Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation, the Alamo Navajo Indian Reservation, and the Tohajiilee Indian Reservation near Albuquerque.[58]

Climate

Much of the Navajo Nation is situated atop the Colorado Plateau.[61] The large variation in altitude (3,080 feet (940 m) to 10,346 feet (3,153 m)) throughout the Navajo Nation is responsible for considerable variations in climate, from an arid, desert climate, comprising 55% of the area, an intermediate steppe region, and the cold, sub-humid climate of the mountainous 8%.[62][58] Average daily temperatures range from 43 °F (6 °C) to 60 °F (16 °C), with a low of 4 °F (−16 °C) in mountainous regions and a high of 110 °F (43 °C) in the desert. Average rainfall is 16–27 inches (410–690 mm) at higher elevations, and 7–11 inches (180–280 mm) in the desert.

Daylight saving time

To maintain consistent time throughout its territory, the Navajo Nation observes daylight saving time (DST) on its Arizona land as well as on its Utah and New Mexico land, even though the rest of Arizona, including the Hopi Reservation, an enclave within the Arizona portion of the Nation, have opted out of DST.[64]

Demographics

Racially, 166,826 were Navajo or other Native American, 3,249 White, 401 Asian or Pacific Islanders, 208 African American, and the remainder identifying some other group or more than one ancestry.[1] The 2010 census counts 109,963 individuals who report speaking a language at home that is neither Asian nor Indo-European.[1] DiscoverNavajo.com reports that 96% of the Navajo Nation is American Indian, and 66% of Navajo tribe members live on Navajo Nation.[65]

The average family size was 4.1, and the average household was home to 3.5 persons. The average household income in 2010 was $27,389.[1]

Nearly half of the enrolled members of the Navajo tribe live outside the nationʼs territory, and the total population is 300,048, as of July 2011.[66] As of 2016, 173,667 Diné lived on tribal lands.[67]

Education

Historically, the Navajo Nation resisted compulsory western education, including boarding schools, as imposed by General Richard Henry Pratt in the aftermath of the Long Walk.[68] This does not negate, however, the scope and breadth of traditional and home education provided by Navajo families and custom since before the US annexation.

Education, and retention of the Navajo student, are significant priorities.[69] Major problems faced by the Nations surrounds building competitive GPAs for students on a national level, coupled with a very high drop-out rate[70] among high school students. Over 150 public, private and Bureau of Indian Affairs schools serve Nation students from kindergarten through high school. Most schools are funded from the Navajo Nation under the Johnson O’Malley program.

The Nation runs community Head Start Programs, the only educational program fully operated by the Navajo Nation government. Post-secondary education and vocational training are available on and off the territory.

The Navajo Nation operates Tséhootsooí Diné Bi'ólta', a Navajo language immersion school for grades K-8 in Fort Defiance, Arizona. Located on the Arizona-New Mexico border in the southeastern quarter of the Navajo Nation, the school strives to revitalize Navajo among children of the Window Rock Unified School District. Tséhootsooí Diné Bi'ólta' has thirteen Navajo language teachers who instruct only in the Navajo language, and no English, while five English language teachers instruct in the English language. Kindergarten and first grade are taught completely in the Navajo language, while English is incorporated into the program during third grade, when it is used for about 10% of instruction.[71]

Secondary education

The Nation has six systems of secondary academic institutions that serve Navajo students, including:

- Arizona public schools

- New Mexico public schools

- Utah public schools

- Bureau of Indian Affairs public schools

- Association of Navajo-Controlled schools

- Navajo Preparatory School, Inc.

Diné College – Tsaile campus

The Navajo Nation operates Diné College, a two-year community college with its main campus at Tsaile in Apache County, Arizona. The college also operates seven other sub-campuses throughout the nation. The Navajo Nation Council founded the college in 1968 as the first tribal college in the United States.[72] Since then, tribal colleges had been established on numerous reservations and now total 32.[72] Diné College has 1,830 students enrolled, of which 210 are degree-seeking transfer students for four-year institutions.

Center for Diné Studies

The college includes the Center for Diné Studies. Its goal is to apply Navajo Sa'ah Naagháí Bik'eh Hózhóón principles to advance quality student learning through Nitsáhákees (thinking), Nahat'á (planning), Iiná (living), and Siihasin (assurance) in study of the Diné language, history, and culture. Students are prepared for further studies and employment in a multi-cultural and technological world.

Navajo Technical University (NTU)

Located in Crownpoint, New Mexico, Navajo Technical University is a tribal university offering various vocational, technical, and academic degrees and certificates. NTU was originally opened in 1979 as the Navajo Skill Center with the intention of providing educational opportunity of the unemployed population of the Navajo Nation. The center has since been renamed multiple time in response to growth and expansion. In 1985 it was renamed Crownpoint Institute of Technology and in 2006 to Navajo Technical College. Finally, in 2013 it was named a "university" in recognition of its program expansion under resolution codified by The Navajo Nation Council.[73][74]

Health concerns

Uranium mining and large-scale effects on the Navajo People

Extensive uranium mining took place in areas of the Navajo Nation before environmental laws were passed or enforced on the control of hazardous wastes of such operations, or their fallout.

Studies have proven the unregulated practices created severe environmental consequences for people living nearby. Several types of cancer occur at much higher rates than the national average in these locations.[75][76] Especially high are the rates of reproductive-organ cancers in teenage Navajo girls, averaging seventeen times higher than the average of girls in the United States.[77]

Residents of the Red Water Pond Road area have requested relocation to a new, off-grid village to be located on Standing Black Tree Mesa while cleanup progresses on the Northeast Church Rock Mine Superfund site, as an alternative to the EPA-proposed relocation of residents to Gallup.[78]

Navajo Neurohepatopathology

The Navajo are uniquely affected by a rare and life-threatening autosomal recessive multisystem disorder called Navajo Neurohepatopathology (NNH), a genetic condition estimated to occur in 1 of every 1,600 live births.[79] The most severe symptoms include neuropathy and liver dysfunction (hepatopathy), both of which may be moderate and progressive or severe and fatal, as it often is in cases that develop in infants (before 6 months of age) or children (1-5 years). Other symptoms include corneal anesthesia and scarring, acral mutilation, cerebral leukoencephalopathy, failure to thrive, and recurrent metabolic acidosis with intercurrent infections.[79]

Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a major health problem among the Navajo, Hopi and Pima tribes, who are diagnosed at a rate about four times higher than the age-standardized U.S. estimate. Medical researchers believe increased consumption of carbohydrates, coupled with genetic factors, play significant roles in the emergence of this chronic disease among Native Americans.[80]

Severe combined immunodeficiency

One in every 2,500 children in the Navajo population inherits severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a genetic disorder that results in children with virtually no immune system. In the general population, the genetic disorder is much more rare, affecting one in 100,000 children. The disorder is sometimes known as "bubble boy disease". This condition is a significant cause of illness and death among Navajo children. Research reveals a similar genetic pattern among the related Apache. In a December 2007 Associated Press article, Mortan Cowan, M.D., director of the Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplant Program at the University of California, San Francisco, noted that, although researchers have identified about a dozen genes that cause SCID, the Navajo/Apache population has the most severe form of the disorder. This is due to the mutations in the gene DCLRE1C, which leads to a defective copy of the protein Artemis. Without the gene, children's bodies are unable to repair DNA or develop disease-fighting cells.[81]

COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic reached the Navajo Nation on March 17, 2020.[82] On March 20, a stay-at-home order was issued after 14 cases of the coronavirus were confirmed, with an 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. curfew enforced.[83]

Beginning April 12, a 57-hour weekend curfew was declared.[84][85] At that point, there were 698 confirmed cases of coronavirus, including 24 deaths, among members of the Navajo Nation living in New Mexico, Arizona and Utah.[84][86] By April 18, there were 1,197 cases.[82] On April 19, the Navajo Department of Health issued an emergency public health order mandating the use of masks outside the home, in addition to existing orders for sheltering in place and nightly and weekend curfews.[87] By April 20, the Navajo Nation had the third-highest infection rate in the United States, after New York and New Jersey.[82]

On April 25, the Nation announced that it was joining 10 other tribes in a lawsuit against the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, over what the plaintiffs said was an unfair allocation of money to the tribes under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act).[88][89] On May 5, $600 million of aid money was delivered to the Navajo Nation, a month after the legislation was signed into law.[90]

As of May 18, 2020, the Navajo Nation surpassed New York as most affected U.S. region per capita,[91] with 4,071 positive COVID-19 tests and 142 fatalities recorded.[92]

As of June 13, 2020, there are 8,187 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with 401 deaths from the virus.[93] By December 27, 2020, the number of confirmed cases had reached 22,277, with 777 fatalities.[94]

Economy

An important part of the Navajo economy and culture is based on the raising of sheep and goats. Navajo families process the wool and sell it for cash, or turn it into yarn and produce blankets and rugs for sale. The Navajo are noted for their skill in creating turquoise and silver jewelry. Navajo artists have other traditional arts, such as sand painting, sculpture, and pottery.

The Navajo Nation has created a mixture of industry and business which has provided the Navajo with alternative opportunities to traditional occupations. The Nation's median cash household income is around $20,000 per year. However, using Federal standards, unemployment levels fluctuates between 40 and 45%. About 40% of families live below the Federal poverty rate.[95]

Natural resources

Mining – especially of coal and uranium provided significant income to both the Navajo Nation and individual Navajos in the second half of the 20th century.[96] Many of these mines have closed. In the early 21st century, mining still provides significant revenues to the tribe in terms of leases (51% of all tribal income in 2003).[97] Individual Navajos are part of the 1,000 people employed in mining.[98]

Coal

The volume of coal mined on the Navajo Nation land has declined in the early 21st century. The Chevron Corporation's P&M McKinley Mine was the first large-scale surface coal mine in New Mexico when it opened in 1961. It closed in January 2010.[99] Peabody Energy's Black Mesa coal mine, a controversial strip mine, was shut down in December 2005 because of its environmental impact and lost an appeal to reopen in January 2010.[100] The Black Mesa mine fed the 1.5 GW Mohave Power Station at Laughlin, Nevada, via a slurry pipeline that used water from the Black Mesa aquifer. The nearby Kayenta Mine used the Black Mesa & Lake Powell Railroad to move coal to the former Navajo Generating Station (2.2 GW) at Page, Arizona. The Kayenta mine provided the majority of leased revenues for the tribe. The Kayenta mine also provided wages to those Navajos who were part of its 400 employees.[101] The Navajo Mine opened in 1963 near Fruitland, New Mexico, and employs about 350 people. It supplies sub-bituminous coal to the 2 GW Four Corners Power Plant via the isolated 13-mile Navajo Mine Railroad.[102] Parts of the Navajo Nation acquired the mine and three mines in Montana and Wyoming.[103]

Uranium

The uranium market, which was active during and after the second World War, slowed near the end of that period. The Nation has suffered considerable environmental contamination and health effects as a result of poor regulation of uranium mining. As of 2005, the Navajo Nation has prohibited uranium mining altogether within its borders.

Oil and natural gas

There are developed and potential oil and gas fields on the Navajo Nation. The oldest and largest group of fields is in the Paradox Basin in the Four Corners area. Most of these fields are located in the Aneth Extension in Utah but there are a few wells in Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. The first well was drilled in the Aneth Extension in 1956. In 2006 the Paradox Basin fields were injected with water and carbon dioxide to increase declining production.[104] There are also wells in the Checkerboard area in New Mexico that are on leased land owned by individual Navajos.

The selling of leases and oil royalties have changed over the years. The Aneth Extension was created from Public Domain lands as part a 1933 exchange for lands flooded by Lake Powell. Congress appointed Utah as trustee on behalf of Navajos living in San Juan County, Utah for any potential revenues that came from natural resources in the area. Utah initially created a 3-person committee to make leases, receive royalties and improve the living conditions for Utah Navajos. As the revenues and resulting expenditures increased, Utah created the 12 member Navajo Commission to do the operational work. The Navajo Nation and Bureau of Indian Affairs are also involved.[105]

There are several Navajo organizations that deal with oil and gas. The Utah Diné Corporation is a nonprofit organization established to take over from the Navajo Commission. The Navajo Nation Oil and Gas Company owns and operates oil and natural gas interests primarily in New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah.[106] Federally incorporated, it is wholly owned by the Navajo Nation.[107]

Renewables

In early 2008, the Navajo Nation and Houston-based IPP entered into an agreement to monitor wind resources, with the potential to build a 500-megawatt wind farm some 50 miles (80 km) north of Flagstaff, Arizona. Known as the Navajo Wind Project, it is proposed as the second commercial wind farm in Arizona after Iberdrola's Dry Lake Wind Power Project between Holbrook and Overgaard-Heber. The project is to be built on Aubrey Cliffs in Coconino County, Arizona.[108]

In December 2010, the President and Navajo Council approved a proposal by the NTUA, an enterprise of the Navajo Nation and Edison Mission Energy, to develop an 85-megawatt wind project at Big Boquillas Ranch, which is owned by the Navajo Nation and is located 80 miles west of Flagstaff. NTUA plans to develop this to a 200-megawatt capacity at peak. This has been planned as the first majority-owned native project; NTUS was to own 51%. An estimated 300–350 people will construct the facility; it will have 10 permanent jobs.[108] In August 2011, the Salt River Project, an Arizona utility, was announced as the first utility customer. Permitting and negotiations involve tribal, federal, state and local stakeholders.[109] The project is intended not only as a shift to renewable energy but to increase access for tribal members; an estimated 16,000 homes are without access to electricity.[110]

The wind project has foundered because of a "long feud between Cameron [Chapter] and Window Rock [central government] over which company to back."[111] Both companies pulled out. Negotiations with Clipper Windpower looked promising but that company was put up for sale after the recession.[111]

Parks and attractions

Tourism is important to the Nation. Parks and attractions within traditional Navajo lands include:

- Monument Valley (on the Utah and Arizona border, near the town of Kayenta, Arizona)

- Shiprock Pinnacle (large volcanic remnants, elevation 7,178, located in New Mexico near Shiprock)

- Navajo Mountain (mountain along Utah and Arizona border, elevation 10,318)

- Navajo Nation Tribal Memorial Park

- Chaco Canyon

- Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness

- Canyon De Chelly

- Window Rock Tribal Park

- Navajo Nation Museum

- Navajo Nation Zoological and Botanical Park

- Antelope Canyon

- Lake Powell

- Navajo Bridge

- Little Colorado River Gorge

- Kinlichee Ruins

- Four Corners Monument

- Hubbell Trading Post

- Grand Falls

- Rainbow Bridge National Monument

- Narbona Pass

Navajo arts and craft enterprise

An important small business group on the Navajo Nation is handmade arts and crafts industry, which markets both high- and medium-end quality goods made by Navajo artisans, jewelers and silversmiths. A 2004 study by the Navajo Division of Economic Development found that at least 60% of all families have at least one family member producing arts and crafts for the market.. A survey conducted by the Arizona Hospitality Research & Resource Center reported that the Navajo nation made $20,428,039 from the art and crafts trade in 2011.[112]

Diné Development Corp.

The Diné Development Corporation was formed in 2004 to promote Navajo business and seek viable business development to make use of casino revenues.[113]

Media

Navajo Times

The Navajo Nation is served by various print media operations. The Navajo Times used to be published as the Navajo Times Today. Created by the Navajo Nation Council in 1959, it has been privatized. It continues to be the newspaper of record for the Navajo Nation. The Navajo Times is the largest Native American-owned newspaper company in the United States.[114]

KTNN

Established as a Navajo Nation Enterprise in 1985, KTNN is a commercial station that provides information and entertainment located on AM 660.

Other newspapers

Other newsprint groups also serve the Nation. The media outlets include the Navajo/Hopi Observer,[115] serving Navajo, Hopi and towns of Winslow and Flagstaff, and the Navajo Post, a web-based with print outlet that serves urban Navajos from its offices at Tempe. Non-Navajo papers also target Navajo audiences, such as the Gallup Independent.

See also

- LGBT rights in the Navajo Nation

- Navajo Nation Flag

- Navajo Nation Scenic Byways

- Navajo National Monument

References

- "Demographic Analysis of the Navajo Nation/ Using 2010 Census and 2010 American Community Survey Estimates" Archived 2014-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, Arizona Rural Policy Institute (ARPI), Northern Arizona University

- "History". www.navajo-nsn.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "List of US States by Size, in Square Miles".

- Brenda Norell, "Navajo oppose name change," Indian Country Today, 12 January 1994

- Young, Robert W & William Morgan, Sr. The Navajo Language. A Grammar and Colloquial Dictionary, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1987.

- Denetdale, Jennifer Nez (2007). Reclaiming Dine History: The Legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8165-2420-4.

- "Planting: Diné shares seeds of wisdom". Navajo Times. January 24, 2019. p. A4.

- Singer, James C. (2007). Navajo Nation Government Reform Project (DRAFT) (PDF) (Report). Dine Policy Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 9 Apr 2017.

- Compiled (1973). Roessel, Ruth (ed.). Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press. ISBN 0-912586-16-8.

- Iverson, Peter; Rossel, Monty (2002). Diné: A History of the Navajos. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press.

- "Navajo Nation Treaty of 1868". Navajocourts.org. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "History". 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Hubbell Trading Post. Site History", National Park Service, Accessed 2010-11-05.

- "BRIEF FOR AMICUS CURIAE NEW MEXICO OIL AND GAS ASSOCIATION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER" (PDF). sct.narf.org.

- Compiled (1974). Roessel, Ruth (ed.). Navajo Livestock Reduction: A National Disgrace. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press. ISBN 0-912586-18-4.

- "U.S. v Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886), Filed May 10, 1886". FindLaw, a Thomson Reuters business. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- "United States v. Kagama – 118 U.S. 375 (1886)". Justia. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- "Title 7 Navajo Nation Code". Navajocourts.org. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- 2 Navajo Nation Code §§ 1001, 1002, 1003, 1005 (1995)

- Lee, Tanya. "Navajo group begins process of crafting a constitution", Indian Country Today. 19 June 2006 (retrieved 5 Oct 2009) Archived September 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Yazzie, Robert (11 February 2003) "History of the Courts of the Navajo Nation", Navajo Nation Museum, Library & Visitor Center, archived 3 November 2010 at FreezePage

- Austin, Raymond Darrel (2009), "The Navajo Nation court system", pp. 1–36, page 21 In Austin, Raymond Darrel (2009) Navajo Courts and Navajo Common Law: A Tradition of Tribal Self-Governance, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, ISBN 978-0-8166-6535-8

- "Former justice, legal historian lists problems with electing judges", Navajo Times 29 October 2010, last accessed 3 November 2010

- French, Laurence (2002) Native American Justice, Burnham, Chicago, page 151, ISBN 0-8304-1575-0

- Navajo Tribal Council Resolution No. CO-69-58 (16 October 1958)

- Navajo Tribal Council Resolution No. CMY-39-78 (4 May 1978)

- Advisory Committee of the Navajo Tribal Council (9 November 1983) "Recommending the Rescission and Repeal of Resolution CMY-39-78, Which Established the Supreme Judicial Council, and Revocation of Any Inconsistent Authority" available as an attachment to Navajo Tribal Council Resolution CD-94-85

- Navajo Tribal Council Resolution No. CD-94-85 (4 December 1985)

- "Judicial Districts of the Navajo Nation" Navajo Courts webpage, 29 May 2010, last accessed 3 November 2010

- "Public Guide to the Navajo Nation Courts". Navajocourts.org. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-05. Retrieved 2014-12-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Majority of Diné vote for 24-member council, line-item veto for president", The Navajo Times Online

- David E. Wilkins, The Navojo Political Experience, 1999, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., pp. 81–82.

- David E. Wilkins, The Navajo Political Experience, 1999, Chapter 9.

- Tom Becenti, World War II vet, peacemaker, served Crownpoint Judicial District until he retired in 1977, Albuquerque Journal, April 1, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- NM mourns long-time state senator John Pinto, The NM Political Report, Andy Lyman, May 24, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "2014 Navajo Nation Election Calendar" (PDF). Navajoelections.navajo-nsn.gov. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ABQJournal News Staff. "Disqualified Navajo candidate appeals". Abqjournal.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Hearing Officer Rules against Navajo Nation Presidential Hopeful". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 2015-01-06.

- "Deschene disqualified, has 10 days to appeal". Navajo Times. 9 October 2014.

- "Navajo presidential election remains in limbo". The Washington Times.

- "Navajo high court orders election postponed". Yahoo News. 24 October 2014.

- "Deschene Out of Navajo Election, Presidential Vote Looks to Be Postponed". Indian Country Today Media Network.com. Archived from the original on 2015-01-07. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- "Navajo Nation candidate Chris Deschene won't halt campaign". Indianz.

- Arizona Capitol Times: Navajo Nation Council passes emergency language requirement repeal. October 23, 2014. Accessed February 15, 2015.

- "Navajo Nation Presidential Candidate Suspends Campaign". Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Navajo Nation Presidential Candidate Suspends Campaign". Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Navajo President vetoes bill, Navajo Nation election still in doubt". Blog for Arizona. 29 October 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-05. Retrieved 2015-01-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Navajo Post Newspaper". Archived from the original on 2015-01-05.

- "Navajo Nation President to Remain in Office". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 2015-07-30.

- "Navajo Nation president sworn in after contentious race", Al-Jazeera (US), 12 May 2015; accessed 12 December 2016

- "No longer in the dark: Navajo Nation homes get electricity". ABC 15. 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- "Palestinians, Israelis occupy Navajo consciousness". America.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Environmental Setting 3–1 to 3–11" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency. 4 September 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- Comerford, Kevin. "Checkerboard Reservation, New Mexico". The Tony Hillerman Portal. University of New Mexico Libraries. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- "Climate and Biota". Navajo Nation. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- Rissetto, Adriana C. "Geography of Dine Bikeyah". xroads.virginia.edu. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- "Arizona Time Zone". Timetemperature.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Fact Sheet". Discovernavajo.com. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- Donovan, Bill. "Census: Navajo enrollment tops 300,000". Navajo Times, 7 July 2011 (retrieved 8 July 2011)

- "NAVAJO NATION COMMUNITY PROFILE" (PDF). nptao.arizona.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-12.

- "BYU Law Review" (PDF). Lawreview.byu.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Jon Reyhner. "Dropout Prevention for American Indian and Alaska Native Students". 2.nau.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Reservation Series: Navajo". Native American / American Indian Blog by Partnership With Native Americans.

- "TSÉHOOTSOOÍ DINÉ BI'ÓLTA' NAVAJO IMMERSION SCHOOL". Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Marjane Ambler, "While globalizing their movement, tribal colleges import ideas", Tribal College Journal of American Indian Higher Education, Vol. 16 No.4, Summer 2005, accessed 7 July 2011 Archived March 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Vandever, Daniel (August 1, 2013). "Navajo Tech becomes a University". Journal of American Indian Higher Education. 25.

- "About Navajo Technical University - Navajo Technical University | Crownpoint, NM". www.navajotech.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- Raloff, 2004

- Laurel Morales (April 10, 2016). "For The Navajo Nation, Uranium Mining's Deadly Legacy Lingers". Weekend Edition Sunday. NPR.

- Snow, Nancy (1996). In the Company of Others: Perspectives on Community, Family, and Culture. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8476-8145-7.

- Ford, Will (January 18, 2020). "A radioactive legacy haunts this Navajo village, which fears a fractured future". Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- Karadimas, Charalampos L.; Vu, Tuan H.; Holve, Stephen A.; Chronopoulou, Penelope; Quinzii, Catarina; Johnsen, Stanley D.; Kurth, Janice; Eggers, Elizabeth; Palenzuela, Lluis; Tanji, Kurenai; Bonilla, Eduardo (28 June 2009). "Navajo Neurohepatopathy Is Caused by a Mutation in the MPV17 Gene". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 79 (3): 544–548. doi:10.1086/506913. PMC 1559552. PMID 16909392.

- American Indians and Alaska Natives and Diabetes. National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse.

- Fonseca, Salt Lake Tribune, B10

- "Coronavirus batters the Navajo Nation, and it's about to get worse". Nbcnews.com. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- Sunnie R. Clahchischiligi (2019-01-31). "Opinion | The Navajo Nation Is Facing the Coronavirus, Too - The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- Silverman, Hollie (2020-04-12). "The Navajo Nation is under a weekend curfew to help combat the spread of coronavirus - CNN". Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- "Public Health Emergency Order No. 2020-005" (PDF). navajo-nsn.gov. April 5, 2020.

- "101 new positive cases of COVID-19 and two more deaths reported, rapid testing to soon become available" (PDF). navajo-nsn.gov. April 11, 2020.

- "Navajo Nation orders mandatory coronavirus masks as minorities continue to be hardest hit". Vox. 2020-04-19. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- Guzman, Joseph (2020-04-23). "Navajo Nation joins lawsuit against US for 'fair share' of coronavirus funding". TheHill. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- "Navajo Nation to sue US government over lack of coronavirus funding – Channel 4 News". Channel4.com. 2020-04-25. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- Klemko, Robert (2020-05-11). "Coronavirus has been devastating to the Navajo Nation, and help for complex fight has been slow". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- Hollie Silverman; Konstantin Toropin; Sara Sidner; Leslie Perrot. "Navajo Nation surpasses New York state for the highest Covid-19 infection rate in the US". CNN. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "COVID-19 Across the Navajo Nation". Navajo Times. 2020-04-06. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Navajo Nation Coronavirus Death Toll Now More Than 400". associated press. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- "Navajo Nation reports 122 new COVID-19 cases, 10 more deaths". KOB 4. 2020-12-27. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "Facts at a glance – based on 2000 census data". Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- See the three volumes produced by the Bureau of Indian Affairs 1955–1956: Kiersch, George A. (1956) Mineral Resources, Navajo-Hopi Indian Reservations, Arizona-Utah: Geology, Evaluation, and Uses, volumes 1–3, United States. Bureau of Indian Affairs, University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona, OCLC 123188599

- "Fast Facts". Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Coal Mining On Navajo Nation". Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Facility Description of NM Environment Department 2016 Compliance Inspection Report" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Administrative Law Judge Decision" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 14, 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- "Kayenta Mine". Archived from the original on 2017-04-03. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "history". Navajo-tec.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-24. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Karl Cates and Seth Feaster (31 January 2020). "IEEFA U.S.: Navajo-owned energy company is in trouble". Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2017-10-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "SF" (PDF). Gpo.gov. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Navajo Nation Oil and Gas Company, Inc.: Private Company Information – Bloomberg". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "Welcome To The Navajo Nation Oil And Gas Company". Nnogc.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ICTMN Staff, "Navajo-Owned Wind Farm in Works in Arizona", Indian Country Today, 17 August 2011; accessed 12 December 2016

- Alastair Lee Bitsoi, "Wind project holds promise for tribe", Navajo Times, 4 August 2011; accessed 12 December 2016

- Gerald Carr, "Asserting Treaty Rights to Harness the Wind on the Great Lakes", American Indian Law Journal, Fall 2013; accessed 12 December 2016

- [ Cindy Yurth, "Waiting for a fair wind"], Navajo Times, 29 November 2012; accessed 12 December 2016

- Arizona Hospitality Research & Resource Center. "2011 Navajo Nation Visitor Survey" (PDF). navajobusiness.com. Northern Arizona University. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Diné Development Corporation". Archived from the original on 2008-05-17.

- Kristi Eaton (AP), "National Native American magazine going digital", Associated Press- The Big Story, 14 July 2013; accessed 8 December 2016. Note: In 2013 journalist Tim Giago, founder of Indian Country Today, said that the Navajo Times was "the largest Indian newspaper in America."

- "Navajo-Hopi Observer – Navajo & Hopi Nations, AZ". Nhonews.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.