Pune district

Pune District is in the state of Maharashtra, India. The district's population was 9,429,408 in the 2011 census, Makes it the fourth-most-populous district amongst India's 640 districts.[2] This district has an urban population of 58.08 percent of its total.[3] It is one of the most industrialized districts in India. In recent decades it has also become a hub for Information technology.

Pune District

The Queen of Deccan | |

|---|---|

District of Maharashtra | |

Visapur Fort, Pune | |

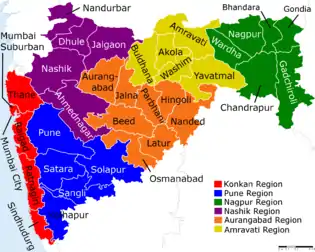

Location of Pune district in Maharashtra | |

| Country | |

| State | Maharashtra |

| Division | Pune Division |

| Headquarters | Pune |

| Government | |

| • Lok Sabha constituencies |

|

| • Vidhan Sabha constituencies | 21 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,642 km2 (6,039 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 9,429,408 |

| • Density | 600/km2 (1,600/sq mi) |

| Demographics | |

| • Literacy | 87.19%[1] |

| • Sex ratio | 919 |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| Major highways | NH-48, NH-65, NH-60 |

| Website | pune |

History

The district has a long human history. The town of Junnar and the Buddhist caves at Karla date back more than two thousand years, and visitors to Junnar were recorded in the 1400s. The region was under Islamic rule from the 13th to the 17th centuries. During the 17th century, the Marathas under Shivaji laid the foundation for an independent kingdom. The Peshwas, who ruled the expanded Maratha empire, established their headquarters in the small town of Pune and developed it into a large city. The city and district became part of the British Raj in the 19th century. Many early Indian nationalists and Marathi social reformers came from the city.

Ancient and medieval history

According to archaeological discoveries of the Jorwe culture in Chandoli and Inamgaon, portions of the district have been occupied by humans since the Chalcolithic (the Copper Age, 5th–4th millennium BC).[4] Many ancient trade routes linking ports in western India (particularly those of coastal Konkan) with the Deccan Plateau pass through the district. The town of Junnar has been an important trading and political center for the last two thousand years, and it was first mentioned by Greco-Roman travellers in the early first millennium AD.[5][6][7] The Karla Caves in Karli, near Lonavala, are near the Western Ghats and a major ancient trade route running eastward from the Arabian Sea to the Deccan Plateau. The caves are a complex of ancient Indian Buddhist rock-cut shrines which were developed from the second century BC to the fifth century AD; the oldest of the shrines is believed to date to 160 BC. Traders and Satvahana rulers financed construction of the caves.[8] Buddhists, identified with commerce and manufacturing through their early association with traders, tended to locate their monasteries in natural formations near major trade routes to provide lodging for travelling traders.[9] Inscriptions at Karla and Junnar suggest that in the early part of the Common Era, the area was controlled by the Shaka ruler Nahapana.[10] Coins found further east in the district, near Indapur, suggest that the region may have been controlled by the Traikutaka king Dahragana in 465 AD; silver coins found at Junnar suggest that the region may also have been ruled by Andhra kings.[11]

The first reference to the Pune region is found on two copper plates, dated to 758 and 768 AD and issued by the Rashtrakuta ruler Krishna I. The plates call the region "Puny Vishaya" and "Punaka Vishaya", respectively. The Pataleshwar rock-cut temple complex was built during this time, and the area included Theur, Uruli, Chorachi Alandi, and Bhosari.[12] The region became part of the Yadava Empire of Deogiri from the ninth to the 13th centuries.

The Muslim Khalji rulers of the Delhi Sultanate overthrew the Yadavas in 1317, beginning three hundred years of Islamic control. The Khalji were followed by another sultanate dynasty, the Tughlaqs. A Tughlaq governor on the Deccan Plateau rebelled and created the Bahamani Sultanate, which later dissolved into the Deccan sultanates. During the 1400s, Russian traveler Afanasy Nikitin spent many months in Junnar during the monsoon season and vividly describes life in the region under Bahamani rule.[13] The fort at Chakan played an important role in the history of the Deccan sultanates.[14] The Bahamani Sultanate broke up in the early 16th century; the Nizamshahi kingdom controlled the region for most of the century, with Junnar its first capital.[15] During the early 1600s, the Nizam Shahi general Malik Ambar moved his capital there.[16]

.jpg.webp)

Deccan sultanates and the Bhosale jagir

The district became politically important when the Nizamshahi capital was moved to Junnar at the beginning of the 16th century. The Bhosale family received a jagir (land grant), and control of the region shifted among the Bhosale rulers, the sultanates and the Mughals during the century. The district was central to the founding of the Maratha Empire by Shivaji.

Nizamshahi

With the establishment of Nizamshahi rule, with Ahmednagar its headquarters, nearly all of the region was controlled by the Nizamshahi. It was formed into a district (or sarkar), with sub-divisions (paragana) and smaller ranges (prant or desh). Revenue collection was delegated to important chieftains who were henchmen of the Nizamshahi.

At Ahmednagar, the Sultan bore the brunt of a heavy attack from Mughal armies who converged on the capital in 1595. To rally the strongest possible local support against the Mughal invaders, and stabilise the territories ruled by Ahmednagar, local Maratha chieftains were given increased power. Amongst the chieftains was Maloji, who was made a raja in 1595; the districts of Pune and Supa were given to him as a jagir (fief). Maloji was also given charge of the forts at Shivneri and Chakan, which played an important role in the district's early political history.[17]

In 1600, Ahmednagar was captured by the Mughals. Nizamshahi minister Malik Ambar raised Murtaza Nizam Shah II to the throne, with its temporary headquarters at Junnar.[15] For nearly a generation, Ambar guided the Nizamshahi kingdom and the Pune region benefited from his leadership. By his death in 1626, the region's revenue system was sound and fair.

Bhosale jagir under the Adilshahi

The Pune region was administered as a jagir during much of the 17th century by Maloji Bhosale, his son Shahaji and his grandson Shivaji. Its nominal sovereignty changed with shifting allegiances of the Bhosale family. In 1632, Shahaji forsook the Mughals and accepted the friendship of the Adilshahi rulers of Bijapur (the traditional rivals of Ahmadnagar Sultanate).

After the fall of the Ahmadnagar (Nizamshahi) Sultanate, its territory was divided between the Adilshahi and the Mughals with Pune region going to the former. Shahaji refused to surrender Junnar (the seat of the Nizamshahi dynasty) before he finally capitulated. However, Shahaji was apparently considered important enough by the Adilshah to play a key role in the new regime's administration. His jagir was confirmed, continuing the region's connection with the Bhosale family.[18]

Shivaji and the Mughals

Shahaji's second son, Shivaji (founder of the Maratha Empire), was born on the hill fort of Shivneri near Junnar on 19 February 1630.[19][20][21][22] Shivaji was named after a local deity, the goddess Shivai.[23] His mother was Jijabai, the daughter of Lakhuji Jadhavrao of Sindhkhed (a Mughal-allied sardar claiming descent from a Yadav royal family from Devagiri.[24][25]

Shahaji appointed Dadoji Konddeo administrator of the Pune jagir (which was restored to him after he joined the Adilshahi service in 1637), and was based in Bengaluru as the Adilshah commander. Konddeo established complete control over the Maval region, winning over (or subduing) most of the local Maval leaders.[26] He rebuilt the settlement of Pune, and prominent families who had left the town during its 1631 destruction by the Adilshahi general Murar Jaggdeo returned.[27] Shahaji selected Pune as the residence of his wife Jijabai and son Shivaji, and Konddeo oversaw the construction of their Lal Mahal palace.

Among Kondadeo's reported reforms was a tax of one-fourth the cash equivalent of a land's yield, and the Fasli calendar was introduced at this time. He is said to have focused on the western Pune region, and has been credited with overseeing Shivaji's education and training.[28][29][30] Kondadeo died in 1647, and Shivaji became his father's deputy.

Many of Shivaji's comrades (and, later, a number of his soldiers) came from the Maval region in the district's western mountains, including Yesaji Kank, Suryaji Kakade, Baji Pasalkar, Baji Prabhu Deshpande and Tanaji Malusare.[31] Shivaji traveled the hills and forests of the Sahyadri range with his Maval friends, acquiring skills and familiarity with the land which would be useful in his military career.[32] [33] Around 1645, the teenaged Shivaji first expressed his concept of Hindavi Swarajya (Indian self-rule) in a letter.[34][35][lower-alpha 1] According to legend, he took an oath to that effect at the temple of Raireshwar near Bhor in the district.[39]

Shivaji began his rule in 1648 of the Pune region, taking possession of the key Torna Fort and controlling the Chakan and Purandar forts and raiding Junnar. He moved his administration to the newly built Rajgad in 1648 and a year later, when Muhammad Adil Shah of Bijapur took Shahaji hostage, restrained his expansionist schemes.[40]

During the late 1640s and 1650s, Shivaji controlled the Pune district and beyond. Rajgad was his seat of government until his 1674 coronation.[40]

During the 1660s, the Mughals under Aurangzeb began paying attention to Shivaji. Pune and the region's forts frequently changed hands between the Mughals and Shivaji.[41] In the Treaty of Purandar (1665), signed by the Mughal general Mirza Jaisingh and Shivaji, Shivaji ceded control of a number of forts in the district to the Mughals.[42] Shivaji recaptured many of these forts when the truce ended.

He was succeeded on the Marathi throne by his eldest son, Sambhaji, in 1680. Shortly afterwards, the Mughal army under Aurangzeb moved into the Deccan Plateau and remained there for nearly three decades. Sambhaji was captured and executed, at Aurangzeb's order, in the village of Tulapur at the confluence of the Bheema and Indrayani Rivers.[43][44] According to other accounts, Sambhaji's remains were fed to dogs.[45]

The period following his 1689 death was one of political ferment in the Deccan Plateau, and the Pune region experienced major fluctuations in administrative authority. Shivaji's younger son, Rajaram I, ruled after his brother's death. He spent most of his time in Gingee, fighting the Mughal siege. Before the Mughals captured Gingee, Rajaram returned to Maharashtra and died in Sinhagad in 1700. Ambikabai,[46] one of his widows, committed sati at Rajaram's death.[47] The Bhimthadi (or Deccani) horse was developed in the region under Maratha rule by crossing Arabian and Turkic breeds with local ponies.[48][49]

Peshwa rule (1714–1818)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Shivaji's grandson, Shahu I, appointed the Chitpavan Brahmin Balaji Vishwanath as his Peshwa in 1714. Vishwanath received the area around Pune from the grateful mother of one of Shahu's ministers for saving her son's life.[50] In 1718, Shahu sent him to Delhi to assist the Sayyads; in return for this help, Muhammad Shah (the Mughal emperor in Delhi) granted Shahu sardeshmukhi rights for Pune, Supa, Baramati, Indapur and Junnar. Shahu appointed Baji Rao I Peshwa in 1720, succeeding his father.[51] Baji Rao moved his administration from Saswad to nearby Pune in 1728, laying the foundation for turning a kasbah into a large city.[52][53] Pune grew in size and influence as Maratha rule extended through the subcontinent in subsequent decades. A well-known saying in the era before the third battle of Panipat was that the "ponies of Bhimthadi[48] drank the water of the Indus river".

Pune under the Peshwas

Pune gained more influence under the rule of Baji Rao I's son, Balaji Baji Rao (Nanasaheb). Maratha influence waned after the disastrous 1761 Battle of Panipat, and the Nizam of Hyderabad looted the city. It (and the empire) recovered during the brief reign of Peshwa Madhavrao. The rest of the Peshwa era was rife with family intrigue and political machinations. The leading role was played by the ambitious Raghunathrao, the younger brother of Nanasaheb, who wanted power at the expense of his nephews Madhavrao I and Narayanrao. After Narayanrao's 1775 murder by order of Raghunathrao's wife, power was exercised in the name of his son Madhavrao II by a regency council led by Nana Fadnavis for most of the century.[54] Under Peshwa rule, the urban elite came from the Chitpavan Brahmin community; they were the military commanders, the bureaucrats and the bankers, and had ties to each other by marriage.[55]

Nanasaheb built a lake in Katraj, on the city's outskirts, and a still-operational underground aqueduct to bring water from the lake to Shaniwar Wada.[56] The city received an underground sewage system in 1782 which discharged into the river.[27][57] Pune prospered during Nanasaheb's reign. On the southern fringe of the city, he built a palace on the Parvati Hill, developed a garden known as Heera Baug, and dug a lake near the hill with a Ganesha temple on an island in its centre which is called Sarasbaug. Nanasaheb also developed new commercial, trading, and residential localities: Sadashiv Peth, Narayan Peth, Rasta Peth and Nana Peth. During the 1790s, the city had a population of 600,000. In 1781, after a city census, a household tax (gharpatti) was levied on the more affluent: one-fifth to one-sixth of the property value.[58]

Order in Peshwa Pune was maintained by the kotwal, who was a police chief, magistrate and municipal commissioner and whose duties included investigating, levying and collecting fines for offences. The kotwal was assisted by police officers who manned the chavdi (police station), and clerks collected fines and paid informants who provided intelligence. Crimes included illicit affairs, violence and murder; in the case of murder, sometimes only a fine was imposed. Inter-caste or inter-religious affairs were also resolved with fines.[59] Although the kotwal's salary was as high as 9,000 rupees per month, it included officer salaries (mainly from the Ramoshi caste).[60] The best-known kotwal in Pune during Peshwa rule was Ghashiram Kotwal, and the city's police force was admired by European visitors.[61]

The patronage of the Brahmin Peshwas resulted in Pune's expansion, with the construction of about 250 temples and bridges (including the Lakdi Pul and the temples on Parvati Hill).[62] Many temples like Maruti, Vithoba, Vishnu, Mahadeo, Rama, Krishna and Ganesha temples were built during this era. Their patronage extended to 164 schools (pathshalas) in the city which taught Hindu holy texts (shastras) to Brahmin men.[63]

Pune also had many public festivals. Major festivals were Ganeshotsav, the Deccan New Year (Gudi Padwa), Holi, and Dasara. Holi at the Peshwa court was celebrated over a five-day period. The Dakshina festival, celebrated in the Hindu month of Shravan (when millions of rupees were distributed), attracted Brahmins from throughout India to Pune.[64][65] The festivals, the building of temples and temple rituals led to religion being responsible for about 15 percent of the city's economy during this period.[66][67][68]

Peshwas and knights residing in the city had individual hobbies and interests; Madhavrao II had a private collection of exotic animals, such as lions and rhinoceros, near the Peshwe Park zoo.[69] The last Peshwa, Baji Rao II, was a strength and wrestling enthusiast. The sport of pole gymnastics(mallakhamba) was developed in Pune under his patronage by Balambhat Deodhar.[70] Many Peshwas and their courtiers were patrons of lavani and Maharashtrian dance, and a number of composers (such as Ram Joshi, Anant Phandi, Prabhakar and Honaji Bala) flourished during this period. The dancers primarily came from the Mang and Mahar castes.[71][72] Lavani used to be essential part of Holi celebrations in the region's Peshwa courts.[73]

Peshwa influence in India declined after the defeat of Maratha forces in the 1761 Battle of Panipat, but Pune remained the seat of power. However, the city's fortunes declined rapidly after the 1795 accession of Baji Rao II. Pune was captured by Yashwantrao Holkar in the 1802 Battle of Pune, precipitating the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803–1805. Peshwa rule ended with the defeat of Baji Rao II by the British East India Company, under the leadership of Mountstuart Elphinstone, in 1818.

British rule and independence

In 1818, the Pune region and the rest of the Peshwa territories came under the control of the British East India Company. Company rule came to an end when, under the terms of a proclamation issued by Queen Victoria, the Bombay Presidency, Pune and the rest of British India came under the British crown in 1858.[74] The governor of the new territories, Mountstuart Elphinstone, appointed a commissioner and left the district's boundaries almost intact. Elphinstone and other British officers enjoyed Saswad and the fertile valley around it.[75]

During the first and second Anglo-Maratha wars, it took four or five weeks to move materials from Mumbai to Pune. An 1804 military road constructed by the British East India Company reduced the journey to four or five days. The company built a macadam road between the two cities in 1830 which permitted mail-cart service.[76][77]

A rail line from Bombay, operated by the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (GIPR), reached Pune in 1858.[78][79] In the following decades, the line was extended east and south of the city. The GIPR extended its line east to Raichur in 1871, where it met the Madras Railway and connected the city to Madras.[80] The metre-gauge Pune-Miraj line was completed in 1886, making the city a rail junction. The Bombay-Poona line was electrified in the 1920s; this cut travel time between the cities to three hours, enabling day trips for events such as the Poona races.[81] Many villages in the west, east and south of the district, such as Lonavla, Uruli Kanchan and Daund, were connected by rail.

Pune's first bus service began in 1941 with the Silver Bus Company, and Tanga (horse-drawn carriage) drivers went on strike in protest.[82] Tangas were a common mode of public transport well into the 1950s, and bicycles were a private vehicle choice in the 1930s.[83]

The British installed a telegraph system in Pune in 1858.[84] According to the 1885 Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona, the city and the GIPR had telegraph offices. In 1928, a relay station was built in Khadki to relay telegraph signals for the Imperial Wireless Chain. In 1885, Pune was a post-distribution hub for the district. There were two post offices in the city, which also offered money-order and savings-bank services.[85]

Areas east of Pune receive less rainfall than areas west of the city adjacent to the Western Ghats. To minimize drought risk, a masonry dam was built on the Mutha River at Khadakwasla in 1878. At the time, the dam was considered one of the world's largest. Two canals were dug on each riverbank to irrigate land east of the city and supply drinking water to the city and its cantonment.[86] In 1890 Poona Municipality spent Rs. 200,000 to install water filtration works.[87]

In the early part 20th century, hydroelectric plants were installed in the Western Ghats between Pune and Mumbai. The Poona electric-supply company, a Tata company, received power from the Khopoli (on the Mumbai side of the Ghats) and Bhivpuri plants near the Mulshi dam.[88] Power was used to electrify trains running between Mumbai and Pune and for industrial and residential use, and a dam was built on the Velvandi River in Bhor.[89][90]

Villages in the district saw rioting in 1875 by peasants protesting Marwari and Gujarati moneylenders. The disturbances involved peasants getting the moneylenders to burn their documents and, in some cases, torching their houses.[91]

Geography and climate

The district is surrounded by Thane district on the northwest, Raigad district on the west, Satara district on the south, Solapur district on the southeast, and Ahmednagar district on the north and northeast. On the leeward side of the Western Ghats, it extends to the Deccan Plateau on the east. Pune is at an altitude of 559 metres (1,863 feet). The district is located between 17.5° and 19.2° north latitude and 73.2° and 75.1° east longitude.

Nine of the district's 15 talukas are identified as drought-prone, covering a total area of 1,562,000 hectares (6,030 sq mi) and a cropped area of 1,095,000 hectares (4,230 sq mi). Of the cropped area, only 116,000 hectares (450 sq mi) are irrigated—nearly half by wells and tanks, and 40 percent by government canals. The district had a population of 4.2 million in 1991, of which 52 percent was rural. There were 1,530 villages in the district.[92]

Its average rainfall is 600 to 700 millimetres (24 to 28 in), most of which falls during the monsoon months (July to October). The area adjacent to the Western Ghats gets more rain than areas further east. The Daund and Indapur talukas experience more-frequent droughts than Maval, on the district's western edge. Temperatures are moderate and rainfall is unpredictable, in tune with the Indian monsoon. Summers, from early March to July, are dry and hot. Temperatures range from 20 to 38 °C (68 to 100 °F), and may reach 40 °C (104 °F). Winter runs from November to February. Temperatures usually hover around 7 to 12 °C (45 to 54 °F), sometimes dipping to 3 °C (37 °F). June is the driest month, and the agricultural sector is considered vulnerable until 20 September.

| Climate data for Pune | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

31.9 (89.4) |

35.4 (95.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

36.9 (98.4) |

31.7 (89.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

17.2 (62.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

11 (0.4) |

40 (1.6) |

138 (5.4) |

163 (6.4) |

129 (5.1) |

155 (6.1) |

68 (2.7) |

28 (1.1) |

4 (0.2) |

741 (29.2) |

| Average precipitation days | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 10.9 | 17.0 | 16.2 | 10.9 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 67.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 291.4 | 282.8 | 300.7 | 303.0 | 316.2 | 186.0 | 120.9 | 111.6 | 177.0 | 248.0 | 270.0 | 288.3 | 2,895.9 |

| Source: HKO | |||||||||||||

Rivers and dams

The Bhima River, the Krishna River's main tributary, rises in the Western Ghats and flows east. All the district's rivers (the Pushpavati, Krushnavati, Kukadi, Meena, Ghod, Bhama, Andhra, Indrayani, Pavna, Mula, Mutha, Ambi, Mose, Shivganga, Kanandi, Gunjavni, Velvandi, Nira, Karha and Velu) flow into the Bhima or its tributaries. Major dams are on the Kukadi, Pushpavati, Ghod, Bhima, Pavna, Bhama, Mula, Mutha (the Temghar and Khadakwasla Dams) and Mose.[93]

Administrative divisions

The district has two municipal corporations in the city of Pune namely Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) and Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC). PCMC, Pune is north western city limits of Pune and its corporation covers Nigdi, Akurdi, Pimpri, Chinchwad and Bhosari. The region was zoned for industrial development by the state of Maharashtra in the early 1960s & later acceded to the city limits.

Pune District is divided into 15 talukas (Junnar taluka, Ambegaon taluka, Khed taluka, Maval taluka, Mulshi taluka, Velhe taluka, Bhor taluka, Haveli taluka, Purandar taluka, Pune City taluka, Indapur taluka, Daund taluka, Baramati taluka and Shirur taluka) and 13 panchayat samitis. The district has 1,866 villages and 21 Vidhan Sabha constituencies: Junnar, Ambegaon, Khed-Alandi, Maval, Mulshi, Haveli, Bopodi, Shivajinagar, Parvati (SC), Kasba Peth, Bhvani Peth, Camp Cantonment, Shirur, Daund, Indapur, Baramati, Purandhar and Bhor. Its four Lok Sabha constituencies are Pune, Baramati, Shirur and Maval (shared with Raigad district).

Cities and towns

Pune. The district has three cantonments, in Camp, Khadki and Dehu Road.

Smaller towns in the district have Nagar Palikas (municipal councils). Most are the taluka headquarters or its main town:

- Alandi

- Baramati (taluka headquarters)

- Bhigwan

- Bhor (taluka headquarters)

- Chakan

- Daund (taluka headquarters)

- Indapur (taluka headquarters)

- Jejuri

- Junnar (taluka headquarters)

- Rajgurunagar (taluka headquarters)

- Lonavla–Khandala

- Narayangaon

- Nasrapur

- Pirangut

- Saswad (taluka headquarters)

- Shirur (taluka headquarters)

- Talegaon Dabhade

- Wadgaon

- Uruli Kanchan

- Mulshi

The growth of the Pune metropolitan area has led to the development of township schemes in the city such as Magarpatta, Amanora and Nanded City and development further from the city in the mountains, such as Lavasa.[94]

District court

Pune District Court administers justice at the district level, and is the principal court of original jurisdiction in civil matters. The district court is also a Sessions Court for criminal matters. It is presided over by a Principal District and Sessions Judge appointed by the state government.

Court decisions are subject to the appellate jurisdiction of Bombay High Court. Pune District Court is under the High Court's administrative control.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 1,095,858 | — |

| 1911 | 1,177,238 | +0.72% |

| 1921 | 1,105,014 | −0.63% |

| 1931 | 1,275,882 | +1.45% |

| 1941 | 1,472,972 | +1.45% |

| 1951 | 1,950,976 | +2.85% |

| 1961 | 2,466,880 | +2.37% |

| 1971 | 3,178,029 | +2.57% |

| 1981 | 4,164,470 | +2.74% |

| 1991 | 5,532,532 | +2.88% |

| 2001 | 7,232,555 | +2.72% |

| 2011 | 9,429,408 | +2.69% |

| source:[95] | ||

Pune district had a population of 9,429,408 in the 2011 census,[2] roughly equal to the nation of Benin.[96] The fourth-most-populous of India's 640 districts,[2] it has a population density of 603 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,560/sq mi).[2] The district's population-growth rate between 2001 and 2011 was 30.34 percent.[2] Pune has a sex ratio of 910 females to every 1,000 males,[2] and a literacy rate of 87.19 percent.[2]

By age, 685,022 were age four or younger; 1,491,352 were between ages five and 15; 4,466,901 were 15 to 59, and 589,280 were 60 years of age or older. For every 1,000 males age 6 and older, there were 919 females. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes made up 12.5% and 3.7% of the population respectively.

Population by language

At the time of the 2011 Census of India, 78.17% of the population in the district spoke Marathi, 10.00% Hindi, 1.89% Urdu, 1.40% Kannada, 1.34% Marwari, 1.30% Telugu and 1.15% Gujarati as their first language.[97]

According to the 2001 census, about 80 percent of the district's population speaks Marathi. Linguistic minorities with more than 100,000 native speakers are Hindi (including Hindi dialects, about 690,000 people), Urdu, Kannada and Telugu. Marwari (a Hindi dialect with Marathi influences), Gujarati, Malayalam (47,912), Tamil (47,504), Sindhi (40,602), Vadari (a Telugu dialect; 35.282), Lamani (a Hindi dialect; 30,604), Punjabi (28,500), Bengali (22,628) and Konkani (19,594) are spoken by over 10,000 people.

Population by religion

According to the 2001 census, most of the district's population is Hindu; there are also significant minorities of Muslims and Buddhists.

| Religion | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Buddhists | 321,948 | 4.45 |

| Christians | 116,661 | 1.61 |

| Hindus | 6,197,349 | 85.69 |

| Jains | 104,073 | 1.44 |

| Muslims | 452,397 | 6.26 |

| Sikhs | 21,938 | 0.30 |

| Other | 11,283 | 0.16 |

| No response | 6,906 | 0.10 |

Education

Primary and secondary education

State primary schools in the cities and district are run by the city corporation and Zilla Parishads, respectively; private schools are operated by charitable trusts. Secondary schools are also run by charitable trusts. All schools are required to undergo inspection by the Zilla Parishad or city corporation.[98] Instruction is primarily in Marathi, English or Hindi, although Urdu is also used. Secondary schools are affiliated with the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) or the Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education. Under the 10+2+3 plan, after completing secondary school students typically enroll for two years in a junior college (also known as pre-university) or a school with a higher secondary curriculum affiliated with the Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education or a central board.

Vocational training

Pune and the district have a number of post-secondary-school industrial training institutes (ITI) run by the government and private trusts which offer vocational training in trades such as construction, plumbing, welding and automobile repair. Successful candidates receive the National Trade Certificate.[99]

Higher education

Pune city has been called the Oxford of the East.[98] The city is home to Savitribai Phule Pune University, and many of its affiliated colleges.The district has a number of central government run educational and training institutes, including the National Defence Academy, the Armed Forces Medical College and the Film and Television Institute of India. The district has many privately run colleges and universities (including religious and special-purpose institutions). Most of the private colleges were founded after the Maharashtra state government of Chief Minister Vasantdada Patil liberalised the education sector in 1982.[100] Politicians and other leaders were instrumental in establishing the private institutions.[101][102]

Other higher-education institutions in the district include:

- Abasaheb Garware College, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- Army Institute of Technology (AIT) - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- B. J. Medical College, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed university)

- Brihan Maharashtra College of Commerce, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- College of Agriculture Pune (COAP) - Affiliated with Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth

- College of Engineering, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule

- Dnyaneshwar Vidyapeeth - Autonomous university

- Shri Shau Mandir Mahavidyalaya[commerce, engineering, agriculture and arts]

Pune University

- Dr. D.Y. Patil College of Engineering, Pune – Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute

- Institute of Management Development and Research, an Autonomous B-School under the aegis of Deccan Education Society

- Fergusson College, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- Government Polytechnic, Pune (diploma courses in engineering)

- Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune

- ILS Law College, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- Indian Naval Training Colleges, Lonavala

- Maharashtra Institute of Technology

- Modern College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- National Chemical Laboratory

- Sinhgad College of Engineering

- Sir Parashurambhau College, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- SNDT Women's University, Pune campus

- Symbiosis International University, Pune

- Vishwakarma Institute of Management

- Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- Nowrosjee Wadia College, Pune - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

- Pune Institute of Computer Technology - Affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University

Economy

Although the district is an industrial center, its economy also has a significant agricultural component. Pune is also considered an educational hub of the state of Maharashtra with students coming from all over India and beyond to attend the numerous colleges and institutes.

Manufacturing

Industrial development began during the 1950s in Pune's outlying areas, such as Hadapsar, Bhosari and Pimpri. The government-run Hindustan Antibiotics was founded in Pimpri in 1954.[103] The area around Bhosari was set aside for industrial development by the newly created Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) in the early 1960s, and the corporation provided business infrastructure.[104] Telco (now Tata Motors) began operations in 1961, boosting the automotive sector. Around 1970, Pune emerged as India's leading engineering region with the expansion of Telco, Bajaj, Kinetic, Bharat Forge, Alfa Laval, Atlas Copco, Sandvik and Thermax; the region vied with Chennai as the "Detroit of India".[105] Growth in the villages of Pimpri, Chinchwad and Bhosari allowed them (and their surrounding areas) to incorporate as separate governing body knows as the Pimpri Chinchawad Municipal Corporation, Pune. The Pune metropolitan area was defined in 1967 as the city, the three cantonment areas and the villages on its outskirts. Some of these villages, such as Kothrud, Katraj, Hadapsar, Hinjawadi and Baner, have become suburbs of Pune.[106] In 2008, General Motors, Volkswagen and Fiat built plants near Pune. MIDC parks founded during the 1990s in Shirur and Baramati have attracted foreign companies.

Information technology

After India's 1991 economic liberalization, Pune began attracting foreign capital from the information-technology and engineering industries. Between 1997 and 2000, IT parks were developed in Aundh and Hinjawadi.[107] goes timely towards Baner, Magarpatta (in hadapsar), EON IT Park Kharadi and viman nagar. According to the study Pune is the fastest growing city in India.

Agriculture

Although the region around Pune is industrialized, agriculture continues to be important elsewhere in the district. Since most arable land is still rain-fed, the southwest monsoon season (between June and September) is crucial to the district's food sufficiency and quality of life. Fluctuations in time, distribution or quantity of monsoon rains may lead to floods or droughts. The eastern part of the district has been historically drought-prone, but irrigation provided by dams, canals and wells have made agriculture less dependent on rainfall.[108] The overtapping of aquifers has led to increased water salinity in the talukas of Purandhar, Baramati, Daund, Indapur and Shirur (in the eastern part of the district), threatening agriculture and the drinking-water supply.[109]

Monsoon crops include rice, jwari and bajri. Other crops include wheat, pulses, vegetables and onions. Ambemohar, a mango-scented rice grown in Bhor taluka and areas near the Western Ghats, is popular throughout Maharashtra. Since it has a low yield, many farmers in the region grow the crossbred Indrayani rice instead.[110]

Major cash crops include sugarcane and oil seeds, including groundnut and sunflower. The district has significant fruit orchards, particularly mango, grape and orange. A winery in Narayangaon produces sparkling wine from locally-grown Thompson seedless grapes.[111] Most growers of cash crops (including cotton) in the district belong to agricultural cooperatives and sugar is produced in mills owned by local cooperative societies whose members of supply sugarcane to the mills.[112] During the last fifty years, the local sugar mills have played an important role in encouraging political participation and have been a stepping stone for aspiring politicians.[113]

Transport

Highways

Pune district has 13,642 kilometres (8,477 mi) of roads. National and state highways crossing the district include:

- NH-48, from Mumbai to Bangalore. The western Dehu Road-Katraj bypass was completed in 1989, reducing traffic congestion in Pune and leading to industrial and housing growth along the bypass.

- NH-60, the Pune-Nashik National Highway

- NH-65, the Pune-Solapur-Hyderabad National Highway

- Yashwantrao Chavan Mumbai Pune Expressway - Work on the six-lane toll road began in 1998 and was completed in 2001.

State highways include:

- Pune-Ahmednagar-Aurangabad State Highway

- Pune-Alandi State Highway

- Pune-Saswad-Pandharpur State Highway

- Pune-Paud Road State Highway

- Talegaon-Chakan State Highway

Public transport

Bus service by private companies was introduced in Pune shortly before the independence. The city took over the service after the independence in 1947 as Poona Municipal Transport (PMT) which later became Pune Municipal Transport. During the 1990s, PMT and Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Transport (PCMT, the bus-service provider in Pimpri-Chinchwad) had a combined fleet of over 1,000 buses. Because municipal transport coverage was patchy, a number of employers in the industrial belt near Pimpri-Chinchwad and Hadapsar offered bus service to their employees.[114] The companies used many more private buses than the municipal providers used.[114] The Pune Municipal Corporation began a bus rapid transit system (India's first) in 2006, but it encountered a number of difficulties. The two municipal bus companies merged in 2007 to form Pune Mahanagar Parivahan Mahamandal Limited (PMPML). The Commonwealth Youth Games were held the following year, which encouraged additional development in north-western Pune and added a fleet of buses running on compressed natural gas (CNG) to the city's streets. Maharashtra State Transport buses began operating in 1951 throughout the state.

During the 1960s, motorized three-wheeled auto rickshaws began replacing horse-drawn tangas in the district's urban areas; their number grew from 200 in 1960 to over 20,000 in 1996. Although Pune was known as the bicycle city of India in the 1930s, motorcycles began replacing bicycles in the 1970s; the number of motorcycles increased from five per 1,000 people in 1965 to 118 per 1,000 in 1995.[114]

Air

Pune Airport (IATA: PNQ) is a civil enclave at Lohegaon Air Base, northeast of the city, with service to a number of domestic and international destinations. Since Pune's air traffic is controlled by the Indian Air Force (IAF),[115] there is occasional conflict between the Airports Authority of India and the IAF over flight schedules or night landings. The airport apron is becoming inadequate to handle the growing number of flights into Pune since the airport's upgrade to international status with flights to Dubai, Singapore and Frankfurt.[116][117] Pune Airport handled about 165 passengers a day in 2004–05, increasing to 250 passengers a day in 2005–06. There was a sharp rise in 2006–07, when the number of daily passengers reached 4,309. In 2010–2011, the number of passengers was about 8,000 a day.[118]

The government of Maharashtra has entrusted responsibility to Maharashtra Airport Development Company (MADC) for the greenfield Chhatrapati Sambhaji Raje International Airport project,[119] in the Purandar area. Baramati Airport, 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from Baramati and 100 kilometres (62 mi) from Pune and used for pilot training and charter flights, was being planned in 2011 as a private-jet hub by Reliance Infrastructure.[120]

Rail

The district's two major rail junctions are Pune Junction and Daund Junction. All rail lines through Pune are broad gauge double track, and are part of Indian Railways' Central Railway zone. The Pune-Mumbai line, the district's most important rail route, was built during the British Raj. Khandala and Lonavala are on this route, which has a number of daily high-speed trains. The Mumbai-Kolhapur line also passes through the district, and other major Indian cities are connected to Pune by rail.

The district's rail lines are:

- Pune-Kalyan (towards Mumbai)

- Pune-Daund

- Daund-Kurduwadi

- Daund-Manmad

- Daund-Baramati branch line (single-track)

- Pune-Miraj (single-track from Pune to Miraj, towards Bangalore)

Although express trains on these routes skip many smaller stations, local "passenger trains" stop at each station. A suburban rail system, operated by Central Railway, connects Pune to its suburbs and neighboring villages west of the city. The system has two routes: from Pune Junction to Lonavala and to Talegaon. Five trains operate on the Pune Junction-Talegaon route, and 18 trains operate on the Pune Junction-Lonavla route.[121] Eight passenger trains run between Pune Junction and Daund as suburban trains, making the Pune-Daund section a third suburban route. Major stations on this route are at Loni Kalbhor and Urali Kanchan.

Healthcare

The district has three government hospitals (Sassoon Hospital, Budhrani and Dr. Ambedkar Hospital) and a number of private hospitals, including MJM Hospital, Sahyadri Hospital, Jahangir Hospital, Sancheti Hospital, Aditya Birla Memorial Hospital, KEM Hospital, Ruby Hall Clinic and Dinanath Mangeshkar Hospital. The above-mentioned hospitals are all in the Pune City.

Tourism

Pune district has been at the center of Maharashtraian and Marathi history for more than four hundred years, beginning with the Deccan sultanates and followed by the Maratha Empire. The district has a number of mountain forts and buildings from these eras, in addition to shrines revered by Marathi Hindus (including five of the eight Ashtavinayaka Ganesha temples). Samadhis of the two most revered Marathi Bhakti saints (Dnyaneshwar and Tukaram) are in Alandi and Dehu, respectively. The main temple of Khandoba, the family deity for most Marathi Hindus, is in Jejuri.[122]

The British designated Pune as the monsoon capital of the Bombay Presidency, and many buildings and parks from the era remain. Hill stations such as Lonavla and Khandala also date back to the Raj, and remain popular with residents of Pune and Mumbai for holidays.[123] The district's mountains, forests and reservoirs are popular for hiking and birdwatching. Bhigwan, a catchment area of the Ujjani Dam, is about from Pune on NH-65, the Pune-Solapur highway. An area of about 18,000 hectares (69 sq mi) has been proposed as a sanctuary for migratory birds.

Pilgrimage sites

Ashtavinayak temples

Ashtavinayak refers to eight historic Ganesh temples in Pune district and adjacent areas. Each of these temples have its own individual legend and history. Five of these temples are situated in Pune district:

- Girijatmak of Lenyadri - A former Buddhist cave on a hilltop near Junnar

- Moreshwar of Morgaon

- Mahaganesh of Ranjangaon

- Chintamani Temple, Theur - The closest Ashtavinayak temple to Pune

- Vigneshwara of Ozar

Forts

A number of historically-important hill forts and castles in the district date back to the Deccan sultanates and Maratha Empire. The forts and surrounding mountains are popular for trekking.[125]

- Anaghaai

- Bhorgiri

- Chakan Fort or Sangramgad - dates back to 15th-century Bahamani rule

- Chavand

- Daulatmangal

- Hadsar

- Induri

- Jivdhan

- Kaawla

- Kailasgad

- Kenjalgad

- Korigad (Korlai)

- Lohagad

- Malhargad (Sonori)

- Morgiri

- Narayangad

- Nimgiri

- Purandar - historically important during the Shivaji and Peshwa eras

- Rajgad - Seat of government for Shivaji for major part of his career before his coronation in 1674

- Rajmachi

- Rohida -

- Shivneri - birthplace of Shivaji in 1630

- Sindola

- Sinhagad (or Kondhana) - Nearest fort to Pune

- Tikona

- Torna Fort or Prachandagad - the first fort captured by the teenaged Shivaji in the 1640s

- Tung Fort or Kathingad

- Vajrangad (Rudramal)

- Visapur Fort

Sports

The Maharashtra cricket team has its home ground in Pune, playing at the new Maharashtra Cricket Association MCA Cricket Stadium in Gahunje. The I-League Pune Football Club plays in the league's First Division, and finished third in the 2009–10 season. FC Pune City plays in the Indian Super League since the league's inception in 2014.

The 1993 National Games were held in Pune, and the new Sports City hosted the Commonwealth Youth Games in 2008. Puneri Paltan, one of ten teams in the professional kabaddi league, has its home ground in Balewadi.

Notes

References

- "Pune District Population Census 2011-2019, Maharashtra literacy sex ratio and density". www.census2011.co.in.

- "District Census 2011". Census2011.co.in. 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- Census data Archived 11 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian history and civilization (Second ed.). New Delhi: New Age International. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9788122411980.

- Margabandhu, C. "Trade Contacts between Western India and the Graeco-Roman World in the early centuries of the Christian era." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient/Journal de l'histoire economique et sociale de l'Orient (1965): 316-322.

- Rath, Jayanti. "QUEENS AND COINS OF INDIA."

- Deo, S. B. "The Genesis of Maharashtra History and Culture." Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 43 (1984): 17-36.

- "Later Andhra Period India". Retrieved 24 January 2007.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York, USA: Grove Press. pp. 123–127. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- Reddy, K.Krishna (2006). Indian History. New Delhi: ata McGraw-Hill Education. p. A-264. ISBN 9780070635777.

- Gadgil, D.R. (1945). Poona A Socio-Economic Survey Part I. Pune, India: Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics. p. 3. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Kantak, M.R. (1991–92). "Urbanization of Pune: How Its Ground Was Prepared". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 51/52: 489–495. JSTOR 42930432.

- Fisher, edited by Michael H. (2007). Visions of Mughal India : an anthology of European travel writing. London: I. B. Tauris. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-1-84511-354-4. Retrieved 6 July 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Eaton, Richard M. (2007). A social history of the Deccan, 1300-1761 (1. pbk. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0521716277.

- "Poona District Nizam Shahis, 1490-1636". Maharashtra. Government of Maharashtra. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Eaton, Richard M. (2005). The new Cambridge history of India (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-521-25484-1. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Joseph G. Da Cunha (1900). Origin of Bombay.

- Richard M. Eaton (17 November 2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761: Eight Indian Lives. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–221. ISBN 978-0-521-25484-7.

- Siba Pada Sen (1973). Historians and historiography in modern India. Institute of Historical Studies. p. 106. ISBN 9788120809000.

- N. Jayapalan (2001). History of India. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-7156-928-1.

- Sailendra Sen (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 196–199. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- "Public Holidays" (PDF). maharashtra.gov.in. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 19.

- Arun Metha (2004). History of medieval India. ABD Publishers. p. 278.

- Kalyani Devaki Menon (6 July 2011). Everyday Nationalism: Women of the Hindu Right in India. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-8122-0279-3.

- Jadunath Sarkar (1919). Shivaji and His Times (Second ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Gadgil, D.R., 1945. Poona a socio-economic survey part I. Economics.

- Duff, Esq. Captain in the first, or grenadier, regiment of Bombay Native Infantry, and late political resident at Satara. In three volumes, James Grant (1826). A History of the Mahrattas, Volume 1 (1921 ed.). London: Oxford University Press. pp. 126–128. Retrieved 27 January 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Haig, Wolseley (27 June 1930). "The Maratha Nation". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. 78 (4049): 873. JSTOR 41358538.

- Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, pp. 20–25.

- Shivaram Shankar Apte (1965). Samarth Ramdas, Life & Mission. Vora. p. 105.

- Edwardes & Garrett, Mughal Rule in India 1995, p. 128.

- Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, pp. 22–24.

- Pagadi, Shivaji 1983, p. 98: "It was a bid for Hindawi Swarajya (Indian rule), a term in use in Marathi sources of history."

- Smith, Wilfred C. (1981), On Understanding Islam: Selected Studies, Walter de Gruyter, p. 195, ISBN 978-3-11-082580-0: "The earliest relevant usage that I myself have found is Hindavi swarajya from 1645, in a letter of Shivaji. This might mean, Indian independence from foreign rule, rather than Hindu raj in the modern sense.

- William Joseph Jackson (2005). Vijayanagara voices: exploring South Indian history and Hindu literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 38. ISBN 0-7546-3950-9.: "Probably the earliest use of a word like 'Hindu' was in 1645 in a phrase in a letter of Shivaji, Hindavi swarajya, meaning independence from foreign rule, 'self-rule of Hindu people'."

- Brown, C. Mackenzie (1984). "Svarāj, the Indian Ideal of Freedom: A Political or Religious Concept?". Religious Studies. 20 (3): 429–441. doi:10.1017/s0034412500016292.

- Husain, Ali Akbar (2011), "The Courtly Gardens of 'Abdul's Ibrahim Nama", in Navina Najat Haiser; Marika Sardar (eds.), Sultans of the South: Arts of India's Deccan Courts, 1323-1687, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 82–83, ISBN 978-1-58839-438-5: "That an obscure "Hindavi-speaking" poet should be elevated to the Persian-influenced court of one of the Deccan's principal sultanates speaks both for Ibrahim 'Adil Shah II's patronage of the local idiom and for his encouragement of 'Abdul and other promising poets..."

- Harish Kapadia (March 2004). Trek the Sahyadris. Indus Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-81-7387-151-1.

- Stewart Gordon (16 September 1993). The Marathas 1600-1818. Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–80. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- "Punediary". Punediary. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Stewart Gordon (16 September 1993). The Marathas 1600-1818. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- Kamal Shrikrishna Gokhale (1978). Chhatrapati Sambhaji. Navakamal Publications. p. 365. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- Organiser. Bharat Prakashan. January 1973. p. 280. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- J. L. Mehta (1 January 2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: Volume One: 1707 – 1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Gokhale, Kamal. Rajaram Chhatrapati in Marathi Vishwakosh. Wai, Maharashtra India: Marathi Vishwakosh.

- Feldhaus, ed. by Anne (1996). Images of women in Maharashtrian literature and religion. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0791428375.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Porter, Valeria; Alderson, Lawrence; Hall, Stephen J. G.; Sponenburg, D. Phillip (2016). Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding. CABI. pp. 460–461. ISBN 978-1845934668. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Bakshi, G.D. (2010). The rise of Indian military power : evolution of an Indian strategic culture. New Delhi: KW Publishers. ISBN 978-8187966524.

- Duff, J. G., 1990. History of the Marathas, Vol. I. Cf. MSG, p.437.

- "पुणे जिल्हा ऐतिहासिक महत्त्वाचे". Manase.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Kosambi, Meera (1989). "Glory of Peshwa Pune". Economic and Political Weekly. 24 (5): 247.

- Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1985). "The Religious Complex in Eighteenth-Century Poona". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 105 (4): 720. doi:10.2307/602730. JSTOR 602730.

- Dikshit, M. G. (1946). "Early Life of Peshwa Savai Madhavrao (Ii)". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 7 (1/4): 225–248. JSTOR 42929386.

- Review: Glory of Peshwa Pune Reviewed Work: Poona in the Eighteenth Century: An Urban History by Balkrishna Govind Gokhale Review by: Meera Kosambi Economic and Political Weekly Vol. 24, No. 5 (Feb. 4, 1989), pp. 247-250

- Khare, K. C., and M. S. Jadhav. "Water Quality Assessment of Katraj Lake, Pune (Maharashtra, India): A Case Study." Proceedings of Taal2007: The 12th World Lake Conference. Vol. 292. 2008.

- Peshwas diaries Volume VIII. p. 354.

- Roy, Kaushik (2013). War, culture and society in early modern south asia, 1740-1849. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-0415728362. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Feldhaus, ed. by Anne (1998). Images of women in Maharashtrian society : [papers presented at the 4th International Conference on Maharashtra: Culture and Society held in April, 1991 at the Arizona State University]. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press. p. 15 51. ISBN 978-0791436608. Retrieved 4 October 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- India. Police Commission and India. Home Dept, 1913. History of Police Organization in India and Indian Village Police: Being Select Chapters of the Report of the Indian Police Commission, 1902-1903. University of Calcutta.

- Jayapalan, N. (2000). Social and cultural history of India since 1556. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 55. ISBN 9788171568260.

- Preston, Laurence W. "Shrines and neighbourhood in early nineteenth-century Pune, India." Journal of Historical Geography 28.2 (2002): 203-215.

- Kumar, Ravinder (2004). Western India in the Nineteenth century (Repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-0415330480.

- Adachi, K., 2001. "Dakshina Rules of Bombay Presidency (1836-1851)". Minamiajiakenkyu, 2001(13), pp. 24-51.

- Kyosuke Adachi, "Dakshina Rules of Bombay Presidency (183(-1851): Its Constitution and Principles", Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies, 13, 2001

- Kosambi, Meera (1989). "Glory of Peshwa Pune". Economic and Political Weekly. 248 (5): 247.

- Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1985). "The Religious Complex in Eighteenth-Century Poona". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 105 (4): 719–724. doi:10.2307/602730. JSTOR 602730.

- "Shaniwarwada was centre of Indian politics: Ninad Bedekar – Mumbai – DNA". Dnaindia.com. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Rao Bahadur Dattatraya Balvanta Parasnis (1921). Poona in Bygone Days. Times Press, Bombay.

- Maguire, Joseph (2011). Sport across asia : politics, cultures and identities 7 (1. publ. ed.). New York and UK: Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-0415884389. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- "Rege, S., 1995. The hegemonic appropriation of sexuality: The case of the lavani performers of Maharashtra. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 29(1), pp.25-37" (PDF).

- Cashman, Richard I. (1975). The myth of the Lokamanya : Tilak and mass politics in Maharashtra. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0520024076. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

peshwa dance.

- SHIRGAONKAR1, VARSHA; RAMAKRISHNAN, K S (2015). "LAVANI LITERATURE AS A SOURCE OF SOCIO-CULTURAL HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL MAHARASHTRA". International Journal of Humanities, Arts, Medicine and Sciences. 3 (6): 41–48. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2000). Queen Victoria: A Personal History. Harper Collins. p. 221. ISBN 0-00-638843-4.

- Martin, Robert Montgomery; Roberts, Emma (20 February 2019). "The Indian empire : its history, topography, government, finance, commerce, and staple products : with a full account of the mutiny of the native troops ..." London ; New York : London Print. and Pub. Co. – via Internet Archive.

- Heitzman, James (2008). The city in South Asia (1st ed.). London: Routledge. p. 125. ISBN 978-0415574266. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

pune.

- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona. Printed at the Government Central Press. 20 February 1885 – via Internet Archive.

junnar.

- Gazetteer of The Bombay Presidency: Poona (Part 2). Government Central press. 1885. p. 156.

- "Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona (2 pts.)". Government Central Press. 3 February 1885 – via Google Books.

- Chronology of railways in India, Part 2 (1870-1899). "IR History: Early Days – II". IFCA. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Kerr, Ian J. (2006). Engines of change : the railroads that made India. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 128. ISBN 0275985644. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "History of PMPML Undertaking". PUNE MAHANAGAR PARIVAHAN MAHAMANDAL LTD. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Gadgil, D .R. (1945). Poona A Socio-Economic Survey Part I. Pune, India: Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics. pp. 240–244. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Gorman, M., 1971. Sir William O'Shaughnessy, Lord Dalhousie, and the Establishment of the Telegraph System in India. Technology and Culture, 12(4), pp. 581-601.

- "Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona (2 pts.)". Government Central Press. 20 February 1885 – via Google Books.

- Gazetteer of The Bombay Presidency: Poona (Part 2). Government Central press. 1885. pp. 16–18.

- Harrison, Mark (1994). Public health in British India : Anglo-Indian preventive medicine 1859-1914. Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 182. ISBN 0521441277. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- Narayan, Shiv (1935). Hydroelectric Plants India. Pune, India. p. 64. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Chatterji, T. D., 1935. Industrial Outlook. Future of Electrical Development in India. Current Science, 3(12), pp. 632-637.

- Sumit Roy, Sumit. "INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE PROCESS OF INNOVATION IN THE INDIAN AUTOMOTIVE COMPONENT MANUFACTURERS WITH REFERENCE TO PUNE AS A DYNAMIC CITY-REGION" (PDF). myweb.rollins.edu. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Catanach, I. J. (1970). Rural credit in western India, 1875-1930; rural credit and the co-operative movement in the Bombay Presidency. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 10–22. ISBN 9780520015951. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

riots 1875.

- Pastala, V.A., 1991. Water for the people--promoting equity and sustainability through watershed developments in rural Maharashtra (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

- Statewise dams in India Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- "Nallathiga, Ramakrishna, Khyati Tewari, Anchal Saboo, and Susan Varghese. "Evolution of Satellite township development in Pune: A Case Study." Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution (2015)".

- Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901

- US Directorate of Intelligence. "Country Comparison:Population". Retrieved 1 October 2011.

Benin 9,325,032

- 2011 Census of India, Population By Mother Tongue

- "Joshi, R., Regulatory Requirements for Starting a School in Poona. Centre for Civil Society, CCS RESEARCH INTERNSHIP PAPERS 2004" (PDF).

- Campbell, James (editor); Melsens, S; Mangaonkar - Vaiude, P; Bertels, Inge (Authors) (2017). Building Histories: the Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Construction History Society Conference. Cambridge UK: The Construction History Society. pp. 27–38. ISBN 978-0992875138. Retrieved 3 October 2017.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bhosale, Jayashree (10 November 2007). "Economic Times: Despite private participation Education lacks quality in Maharashtra". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Dahiwale Vol. 30, No. 6 (Feb. 11, 1995), pp., S. M. (1995). "Consolidation of Maratha Dominance in Maharashtra". Economic and Political Weekly. 30 (6): 341–342. JSTOR 4402382.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Baviskar, B. S. (2007). "Cooperatives in Maharashtra: Challenges Ahead". Economic and Political Weekly. 42 (42): 4217–4219. JSTOR 40276570.

- "Historical Events in Pune". NIC - District-Pune. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- Menon, Sudha (30 March 2002). "Pimpri-Chinchwad industrial belt: Placing Pune at the front". The Hindu Business Line. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Heitzman, James (2008). The city in South Asia. London: Routledge. p. 213. ISBN 978-0415574266. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

pune.

- Joshi, Ashutosh (2008). Town planning regeneration of cities. New Delhi: New India Pub. Agency. pp. 73–84. ISBN 9788189422820.

- Heitzman, James (2008). The city in South Asia. London: Routledge. p. 218. ISBN 978-0415574266. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

pune.

- Sengupta, S. K. "NATIONAL REGISTER OF LARGE DAMS – 2009" (PDF). Central Water Commission - An apex organization in water resources development in India. Central water Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Duraiswami, Raymond A.; Maskare, Babaji; Patankar, Uday (2012). "GEOCHEMISTRY OF GROUNDWATER IN THE ARID REGIONS OF DECCAN TRAP COUNTRY, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA". Memoir Indian Society of Applied Geochemists. 1: 73.

- Bhosale, Jayashree (31 January 2012). "Consumers pay premium price for the look alike of the regional rice varieties". Economic Times. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Verma, L.R.; Joshi, V.K.; (Editors) (2000). Postharvest technology of fruits and vegetables : handling, processing, fermentation, and waste management. New Delhi: Indus Pub. Co. p. 58. ISBN 9788173871085.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "National Federation of Cooperative Sugar Factories Limited". Coopsugar.org. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- Patil, Anil (9 July 2007). "Sugar cooperatives on death bed in Maharashtra". Rediff India. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- "Download Limit Exceeded". citeseerx.ist.psu.edu.

- AAI website, 1 November 2011, archived from the original on 8 February 2012, retrieved 1 February 2012

- "Pune Customs website". Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "Pune airport accorded international status". Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Passenger traffic at Pune airport takes a big leap". Indian Express. 14 October 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Bureau, Our Corporate (10 August 2004). "New airport for Pune". Business Standard India – via Business Standard.

- "Reliance plans Baramati hub for pvt jets". Business Standard. 16 July 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- "Time table of five new trains from city announced - Times of India". The Times of India.

- Feldhaus, Anne (2003). Connected places : region, pilgrimage, and geographical imagination in India (1. ed.). New York: Palgrave macmillan. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-4039-6323-9.

- Incredible India, Maharashtra (PDF).

- Glushkova, Irina. "6 Object of worship as a free choice." Objects of Worship in South Asian Religions: Forms, Practices and Meanings 13 (2014).

- Kapadia, Harish (2003). Trek the Sahyadris (5. ed.). New Delhi: Indus Publ. pp. 19–21. ISBN 9788173871511. Retrieved 3 October 2017.