Madja-as

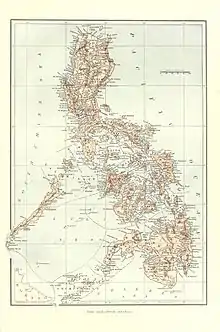

The Confederation of Madya-as was a legendary pre-colonial supra-baranganic polity on the island of Panay in the Philippines. It was mentioned in Pedro Monteclaro's book titled Maragtas. It was supposedly created by Datu Sumakwel to exercise his authority over all the other datus of Panay.[1] Like the Maragtas and the Code of Kalantiaw, the historical authenticity of the confederation is disputed, as no other documentation for Madya-as exists outside of Monteclaro's book.[2]

Confederation of Madya-as | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1200–1569 | |||||||||||||

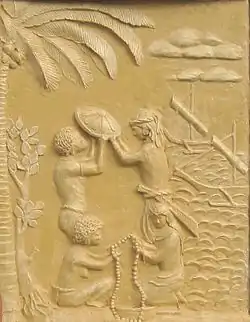

The historical landmark in San Joaquin, Iloilo indicating the spot traditionally referred to as the site of the Barter of Panay. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Sinugbohan Malandog Aklan Irong-Irong | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Proto-Visayan (present-day Aklanon, Kinaray-a, Capiznon, Hiligaynon, and Cebuano in Negros Oriental) (local languages) Old Malay and Sanskrit (trade languages) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Primary Folk religion Secondary Hinduism Buddhism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Kedatuan | ||||||||||||

| Datu | |||||||||||||

• c. 1200–1212 | Datu Puti | ||||||||||||

• 1213–? | Datu Sumakwel | ||||||||||||

• 1365–1437 | Datu Kalantiaw | ||||||||||||

• 1437–? | Datu Manduyog | ||||||||||||

• ?–1565 | Datu Kabnayag | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established by 10 Datus | c. 1200 | ||||||||||||

• Conquest by Spain | 1569 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Gold, Pearls, Barter | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

| Pre-colonial history of the Philippines |

|

|---|

| Barangay government |

| Ruling class (Maginoo, Tumao): Apo, Datu, Lakan, Panglima, Rajah, Sultan, Thimuay |

| Middle class: Timawa, Maharlika |

| Serfs, commoners and slaves (Alipin): Aliping namamahay, Alipin sa gigilid, Bulisik, Bulislis, Horohan, Uripon |

| States in Luzon |

| Caboloan |

| Cainta |

| Ma-i |

| Rajahnate of Maynila |

| Namayan |

| Tondo |

| States in the Visayas |

| Kedatuan of Madja-as |

| Kedatuan of Dapitan |

| Rajahnate of Cebu |

| States in Mindanao |

| Rajahnate of Butuan |

| Sultanate of Sulu |

| Sultanate of Maguindanao |

| Sultanates of Lanao |

| Key figures |

| The book of Maragtas |

| Religion in pre-colonial Philippines |

| History of the Philippines |

| Portal: Philippines |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Philippines |

|

| Timeline |

| Archaeology |

|

|

Origin

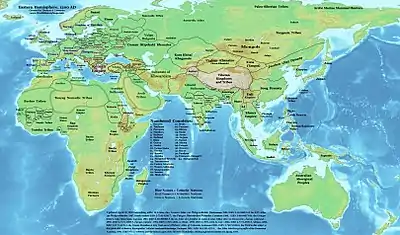

In the aftermath of the Indian Chola invasion of Srivijaya, Datu Puti lead some dissident datus from Borneo (including present day Brunei which then called Vijayapura state of Hindu-Buddhist Srivijaya empire) and Sumatra in a rebellion against Rajah Makatunao who was a Chola appointed local Rajah. The dissidents and their retinue tried to revive Srivijaya in a new country called Madja-as in the Visayas islands (an archipelago named after Srivijaya) in the Philippines.[3]

Madja-as was a pre-colonial chiefdom in Central Philippines. According to ancient tradition recorded by P. Francisco Colin, S.J., an early Spanish missionary in the Philippines,[4] The inhabitants of Panay island in the Philippines were believed to be from North Sumatra; especially from the polity of Pannai, after which the Island of Panay (called Ananipay by the Atis)was named after (i and y being interchangeable in Spanish). It was founded by Pannai loyalists who wanted to reestablish their state elsewhere following an occupation of their homeland.

The polity of Pannai was a militant-nation settled by Warrior-Monastics as evidenced by the Temple ruins in the area as it was allied under the Sri-Vijaya Mandala that defended the conflict-ridden Strait of Malacca. The small kingdom traded-with and simultaneously repulsed any unlicensed Chinese, Indonesian, Indian or Arab navies that often warred in or pirated the strait of Malacca and, for a small country, they were adept at taking down armadas larger than itself - a difficult endeavour to achieve in the strait of Malacca, which was among the world's most hotly contested maritime choke-point where, today, one half of world trade passes through. The naval power of Pannai was successful in policing and defending the straights of Malacca for the Mandala of Srivijaya until the Chola invasion of Srivijaya occurred, wherein a surprise attack from behind, originating from the occupied capital, rendered the militant polity of Pannai vulnerable from an unprotected assault from the back flank. The Chola invaders eventually destroyed the polity of Pannai and its surviving soldiers, royals and scholars were said to have been secreted-out eastwards. In their 450 years of occupying Sumatra, they refused to be enslaved to Islam, Taoism or Hinduism after the polity's dissolution. The people who stayed behind in Pannai, themselves, have an oral tradition wherein they said that the high-borne scholars, soldiers and nobles of Pannai who refused to swear allegiance to a treacherous invading empire, faithfully followed their kings, the "datus" and "fled to other islands."[4]

Colonization

Soon after the expedition had landed, the Malay migrants from Borneo came in contact with the native people of the Island, who were called Atis or Agtas. Some writers have interpreted these Atis as Negritos. Other sources present evidence that they were not at all the original people of Negrito type, but were rather tall, dark-skinned austronesian type. These native Atis lived in villages of fairly well-constructed houses. They possessed drums and other musical instruments, as well as a variety of weapons and personal adornments, which were much superior to those known among the Negritos.[5]

Negotiations were conducted between the newcomers and the native Atis for the possession of a wide area of land along the coast, centering on the place called Andona, at a considerable distance from the original landing place. Some of the gifts of the Visayans in exchange of those lands are spoken of as being, first, a string of gold beads so long that it touched the ground when worn and, second, a salakot, or native hat covered with gold.[6] The term for that necklace which survive in the present Kinaray-a language is Manangyad, from the Kiniray-a term sangyad, which means "touching the ground when worn". There were also a variety of many beads, combs, as well as pieces of cloth for the women and fancifully decorated weapons (Treaty-Blades) for the men. The sale was celebrated by a feast of friendship between the newcomers and the natives, following which the latter formally turned over possession of the settlement.[6] Afterwards a great religious ceremony and sacrifice was performed in honor of the settlers' ancient gods, by the priest whom they had brought with them from Borneo.[6]

The Atis were the ones who referred to the Borneans as mga Bisaya, which some historians would interpret as the Atis' way of distinguishing themselves from the white settlers.[7]

Following the religious ceremony, the priest indicated that it was the will of the gods that they should settle not at Andona, but rather at a place some distance to the east called Malandog (now a Barangay in Hamtik, Province of Antique, where there was both much fertile agricultural land and an abundant supply of fish in the sea. After nine days, the entire group of newcomers was transferred to Malandog. At this point, Datu Puti announced that he must now return to Borneo. He appointed Datu Sumakwel, the oldest, wisest and most educated of the datus, as chief of the Panayan settlement.[6]

Not all the Datus, however, remained in Panay. Two of them, with their families and followers, set out with Datu Puti and voyaged northward. After a number of adventures, they arrived at the bay of Taal, which was also called Lake Bombon on Luzon. Datu Puti returned to Borneo by way of Mindoro and Palawan, while the rest settled in Lake Taal.[8]

The descendants of the Datus who settled by Lake Taal spread out in two general directions: one group settling later around Laguna de Bay, and another group pushing southward into the Bicol Peninsula. A discovery of an ancient tomb preserved among the Bicolanos refers to some of the same gods and personages mentioned in a Panay manuscript examined by anthropologists during the 1920s.[9]

The original Panay settlements continued to grow and later split up into three groups: one of which remained in the original district (Irong-irong), while another settled at the mouth of Aklan River in northern Panay. The third group moved to the district called Hantik. These settlements continued to exist down to the time of the Spanish regime and formed centers, around which the later population of the three provinces of Iloilo, Capiz, and Antique grew up.[9]

The early Bornean settlers in Panay were not only seafaring. They were also a river-based people. They were very keen in exploring their rivers. In fact, this was one of the few sports they loved so much.[10] The Island's oldest and longest epic Hinilawod recounts legends of its heroes' adventures and travels along the Halaud River.

An old manuscript Margitas of uncertain date (discovered by the anthropologist H. Otley Beyer)[11] give interesting details about the laws, government, social customs, and religious beliefs of the early Visayans, who settled Panay within the first half of the 13th century.[9] The term Visayan was first applied only to them and to their settlements eastward in the island of Negros, and northward in the smaller islands, which now compose the province of Romblon. In fact, even at the early part of Spanish colonialization of the Philippines, the Spaniards used the term Visayan only for these areas. While the people of Cebu, Bohol, and Leyte were for a long time known only as Pintados.[12] The name Visayan was later extended to them because, as several of the early writers state (especially in the writings of the Jesuit Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro published in 1801),[13] albeit erroneously, their languages are closely allied to the Visayan "dialect" of Panay.[14] This fact indicates that the ancient people of Panay called themselves as Visayans, for the Spaniards would have otherwise simply referred to them as "people of the Panay". This self-reference as Visayans as well as the appellative (Panay - a riminescence of the State of Pannai) that these people give to the Island manifest a strong sign of their identification with the precursor civilization of the Srivijayan Empire.

Gabriel Rivera, a captain of the Spanish royal infantry in the Philippine Islands, also distinguished Panay from the rest of the Pintados Islands. In his report (dated 20 March 1579) regarding a campaign to pacify the natives living along the rivers of Mindanao (a mission he received from Dr. Francisco de Sande, Governor and Captain-General of the Archipelago), Ribera mentioned that his aim was to make the inhabitants of that island "vassals of King Don Felipe... as are all the natives of the island of Panay, the Pintados Islands, and those of the island of Luzon..."[15]

In Book I, Chapter VII of the Labor Evangelica (published in Madrid in 1663), Francisco Colin, S.J. described the people of Iloilo as Indians who are Visayans in the strict sense of the word (Indios en rigor Bisayas), observing also that they have two different languages: Harayas and Harigueynes,[16] which are actually the Karay-a and Hiligaynon languages.

Social structure

Before the advent of the Spaniards, the settlements of this confederation already had a developed civilization, with defined social mores and structures, enabling them to form an alliance, as well as with a sophisticated system of beliefs, including a religion of their own.

The Datu Class was at the top of a divinely sanctioned and stable social order in a Sakop or Kinadatuan (Kadatuan in ancient Malay; Kedaton in Javanese; and Kedatuan in many parts of modern Southeast Asia), which is elsewhere commonly referred to also as barangay.[17] This social order was divided into three classes. The Kadatuan (members of the Visayan Datu Class) were compared by the Boxer Codex to the titled Lords (Señores de titulo) in Spain.[18] As Agalon or Amo (Lords),[19] the Datus enjoyed an ascribed right to respect, obedience, and support from their Ulipon (Commoner) or followers belonging to the Third Order. These Datus had acquired rights to the same advantages from their legal "Timawa" or vassals (Second Order), who bind themselves to the Datu as his seafaring warriors. "Timawas" paid no tribute, and rendered no agricultural labor. They had a portion of the Datu's blood in their veins. The above-mentioned Boxer Codex calls these "Timawas": Knights and Hidalgos. The Spanish conquistador, Miguel de Loarca, described them as "free men, neither chiefs nor slaves". In the late 17th century, the Spanish Jesuit priest Fr. Francisco Ignatio Alcina, classified them as the third rank of nobility (nobleza).[20]

To maintain purity of bloodline, Datus marry only among their kind, often seeking high-ranking brides in other Barangays, abducting them, or contracting brideprices in gold, slaves and jewelry. Meanwhile, the Datus keep their marriageable daughters secluded for protection and prestige.[21] These well-guarded and protected highborn women were called Binukot,[22] the Datus of pure descent (four generations) were called "Potli nga Datu" or "Lubus nga Datu",[23] while a woman of noble lineage (especially the elderly) are addressed by the inhabitants of Panay as "Uray" (meaning: pure as gold), e.g., Uray Hilway.[24]

Religion

The gods

The Visayans adored (either for fear or veneration) various gods called the Diwatas (A local adaptation of the Hindu or Buddhist Devata). Early Spanish colonizers observed that some of these deities of the Confederation of Madja-as, have sinister characters, and so, the colonizers called them evil gods. These Diwatas live in rivers, forests, mountains, and the natives fear even to cut the grass in these places believed to be where the lesser gods abound.[25] These places are described, even now (after more than four hundred years of Christianization of the Confederacy's territory), as mariit (enchanted and dangerous). The natives would make panabi-tabi (courteous and reverent request for permission) when inevitably constrained to pass or come near these sites. Miguel de Loarca in his Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) described them. Some are the following:

- Barangao . Ynaguinid and Malandok: a trinity of deities invoked before going to war, or before plundering expeditions[26]

- Makaptan: the god who dwells in the highest sky, in the world that has no end. He is a bad god, because he sends disease and death if has not eaten anything of this world, or has not drunk any pitarillas. He does not love humans, and so he kills them.[27]

- Lalahon: the goddess who dwells in Mt. Canlaon, from where she hurls fire. She is invoked for harvests. When she does not grant the people good harvest, she sends them locusts to destroy and consume the crops.[28]

- Magwayen: the god of the oceans; and the father (in some stories the mother) of water goddess Lidagat, who after her death decided to ferry souls in the afterworld.[29]

- Sidapa: another god in the sky, who measures and determines the lifespan of all the new-born by placing marks on a very tall tree on Mt. Madja-as, which correspond to each person who come into this world. The souls of the dead inhabitants of the Confederation go to the same Mt. Madja-as.[29]

Some Spanish colonial historians, including Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, would classify some heroes and demigods of the Panay epic Hinilawod, like Labaw Donggon, among these Diwatas.[30]

Creation of the first man and woman

In the above-mentioned report of Miguel de Loarca, the Visayans' belief regarding the origin of the world and the creation of the first man and woman was recorded. The narrative says:[31]

The people of the coast, who are called Yligueynes, believed that the heaven and earth had no beginning and that there were two gods, one called Captan and the other Maguayen. They believed that the breeze and the sea were married; and that the land breeze brought forth a reed, which was planted by the god Captan. When the reed grew, it broke into two sections, from which came a man and a woman. To the man they gave the name Silalac, and that is the reason why men from that time on have been called lalac; the woman they named Sicavay, and henceforth women have been called babaye...'

One day the man asked the woman to marry him for there were no other people in the world; but she refused, saying they were brother and sister, born of the same reed, with only one know between them. Finally, they agreed to ask the advice from the tunnies of the sea and from the doves of the earth. They also went to the earthquake, which said that it was necessary for them to marry, so that the world might be peopled.

Death

The Visayans believed that when the time comes for a person to die, the diwata Pandaki visits him to bring about death. Magwayen, the soul ferry god, carries the souls of the Yligueynes to the abode of the dead called Solad.[29] But when a bad person dies, Pandaki brings him to the place of punishment in the abode of the dead, where his soul will wait to move on to the Ologan or heaven. While the dead is undergoing punishment, his family could help him by asking the priests or priestesses to offer ceremonies and prayers so that he might go to the place of rest in heaven.[32]

Shamans

The spiritual leaders of the confederation were called Babaylan. Most of the Babaylan were women who, for some reasons, the colonizers described as "lascivious" and astute. On certain ceremonial occasions, they put on elaborate apparel, which appear bizarre to Spaniards. They would wear yellow false hair, over which some kind of diadem adorn and, in their hands, they wielded straw fans. They were assisted by young apprentices who would carry some thin cane as for a wand.[33]

Notable among the rituals performed by Babaylan was the pig sacrifice. Sometimes chicken were also offered. The sacrificial victims were placed on well adorned altars, together with other commodities and with the most exquisite local wine called Pangasi. The Babaylan would break into dance hovering around these offerings to the sound of drums and brass bells called Agongs, with palm leaves and trumpets made of cane. The ritual is called by the Visayans "Pag-aanito".[34]

Integration to the Spanish East Indies

The Spaniards landed in Batan (in Panay's northeastern territory, which is currently called Province of Aklan), in 1565. The Chief of this place, Datu Kabnayag, relocated his capital to what is now called "Guadalupe". Afterwards, however, the datus were overpowered by the Spaniards. Following the Spanish conquest, the locals became Christians. Father Andres Urdaneta baptized thousands of Aklanons in 1565, and consequently these settlements of the Confederation was renamed Calivo.

Legazpi then parceled Aklan to his men. Antonio Flores became encomiendero for all settlements along the Aklan River and he was also appointed in charge of pacification and religious instruction. Pedro Sarmiento; was appointed for Batan, Francisco de Rivera; for Mambusao, Gaspar Ruiz de Morales; and for Panay town, Pedro Guillen de Lievana.

Later (in 1569), Miguel López de Legazpi transferred the Spanish headquarters from Cebu to Panay. On 5 June 1569, Guido de Lavezaris, the royal treasurer in the Archipelago, wrote to Philip II reporting about the Portuguese attack to Cebu in the preceding autumn. A letter from another official, Andres de Mirandaola (dated three days later - 8 June), also described briefly this encounter with the Portuguese. The danger of another attack led the Spaniards to remove their camp from Cebu to Panay, which they considered a safer place. Legazpi himself, in his report to the Viceroy in New Spain (dated 1 July 1569), mentioned the same reason for the relocation of Spaniards to Panay.[35] It was in Panay that the conquest of Luzon was planned, and launched on 8 May 1570.[36]

In 1716, the old Sakup (Sovereign Territory) of Aklan completely fell under the Iberian control, and became Spanish politico-military province under the name of Capiz. And so it remained for the next 240 years. [37]

Early accounts

During the early part of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, the Spanish Augustinian Friar Gaspar de San Agustín, O.S.A. described Panay as: "...very similar to that of Sicily in its triangular form, as well as in its fertility and abundance of provision. It is the most populated island after Manila and Mindanao, and one of the largest (with over a hundred leagues of coastline). In terms of fertility and abundance, it is the first... It is very beautiful, very pleasant, and full of coconut palms... Near the river Alaguer (Halaur), which empties into the sea two leagues from the town of Dumangas..., in the ancient times, there was a trading center and a court of the most illustrious nobility in the whole island."[38]

Miguel de Loarca, who was among the first Spanish settlers in the Island, also made one of the earliest account about Panay and its people according to a Westerner's point of view. In June 1582, while he was in Arevalo (Iloilo), he wrote in his Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas the following observations:

The island is the most fertile and well-provisioned of all the islands discovered, except the island of Luzon: for it is exceedingly fertile, and abounds in rice, swine, fowls, wax, and honey; it produces also a great quantity of cotton and abacá fiber.[39]

"The villages are very close together, and the people are peaceful and open to conversion. The land is healthful and well-provisioned, so that the Spaniards who are stricken in other islands go thither to recover their health."[39]

The Visayans are physically different from the Malays of Luzon, and can be distinguished by the fact that Visayans are fairer in complexion. Because of this trait, there was an old opinion about these Visayans originating from Makassar.[40]

"The natives are healthy and clean, and although the island of Cebu is also healthful and had a good climate, most of its inhabitants are always afflicted with the itch and buboes. In the island of Panay, the natives declare that no one of them had ever been afflicted with buboes until the people from Bohol - who, as we said above, abandoned Bohol on account of the people of Maluco - came to settle in Panay, and gave the disease to some of the natives. For these reasons the governor, Don Gonzalo Ronquillo, founded the town of Arevalo, on the south side of this island; for the island runs north and south, and on that side live the majority of the people, and the villages are near this town, and the land here is more fertile."[39]

"The Ilongga women distinguish themselves in courage, exhibiting feats that are beyond the expectations of their gender."[41]

"The island of Panay provides the city of Manila and other places with a large quantity of rice and meat...[42] As the island contains great abundance of timber and provisions, it has almost continuously had a shipyard on it, as is the case of the town of Arevalo, for galleys and fragatas. Here the ship Visaya was launched."[43]

Another Spanish chronicler in the early Spanish period, Dr. Antonio de Morga (Year 1609) is also responsible for recording other Visayan customs. Customs such as Visayans' affinity for singing especially among their warrior-castes as well as the playing of gongs and bells in naval battles.

Their customary method of trading was by bartering one thing for another, such as food, cloth, cattle, fowls, lands, houses, fields, slaves, fishing-grounds, and palm-trees (both nipa and wild). Sometimes a price intervened, which was paid in gold, as agreed upon, or in metal bells brought from China. These bells they regard as precious jewels; they resemble large pans and are very sonorous. They play upon these at their feasts, and carry them to the war in their boats instead of drums and other instruments.[44]

The American anthropologist-historian William Henry Scott, quoting earlier Spanish sources, in his book "Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society", also recorded that Visayans were a musically minded people who sang almost all the time, especially in battle, saying:

Visayans were said to be always singing except when they were sick or asleep. Singing meant the extemporaneous composition of verses to common tunes, not the performance of set pieces composed by musical specialists. There was no separate poetic art: all poems were sung or chanted, including full-fledged epics or public declamations. Singing was unaccompanied except in the case of love songs, in which, either the male or female singers accompanied themselves with their respective instruments, called kudyapi or korlong. Well-bred ladies were called upon to perform with the korlong during social gatherings, and all adults were expected to participate in group singing on any occasion.[45]

The Book of Maragtas

According to local oral legends and the book entitled Maragtas,[46] early in the 13th century, ten datus of Borneo (Sumakwel, Bangkaya, Paiburong, Paduhinog, Dumangsol, Dumangsil, Dumaluglog, Balkasusa, and Lubay, who were led by Datu Puti) and their followers fled to the sea on their barangays and sailed north to flee from the oppressive reign of their paramount ruler Rajah Makatunaw, at the time of the destruction of the Srivijayan Empire. They eventually reached Panay island and immediately settled in Antique, creating a trade treaty with the Ati hero named Marikudo, and his wife Maniwantiwan, from whom they wanted to purchase the land. A golden salakot and long pearl necklace (called Manangyad) was given in exchange for the plains of Panay. The Atis relocated to the mountains, while the newcomers occupied the coasts. Datu Bangkaya then established a settlement at Madyanos, while Datu Paiburog established his village at Irong-irong (Which is now the city of Iloilo) while Datu Sumakwel and his people crossed over the Madja-as mountain range into Hamtik and established their village at Malandong. Datu Puti left the others for explorations northwards after ensuring his people's safety. He designated Datu Sumakwel, being the eldest, as the commander-in-chief of Panay before he left.

By 1213, Datu Sumakwel invoked a council of datus to plan for common defense and a system of government. Six articles were adopted and promulgated, which came to be known as Articles of Confederation of Madja-as.

The confederation created the three sakups (Sovereign territories) as the main political divisions, and they defined the system of government, plus establishing rights of individuals while providing for a justice system.

As a result of the council, Datu Paiburong was formally installed as commander-in-chief of Irong-irong at Kamunsil, Sumakwel of Hamtik at Malandog, and Bangkaya of Aklan at Madyanos.

Bangkaya ruled his sakup from Madyanos according to local customs and the Confederation of Madja-as' articles. The first capital of Aklan was Madyanos. Commander-in-chief, Datu Bangkaya then sent expeditions throughout his sakup and established settlements in strategic locales while giving justice to this people.[47]

After his election as commander-in-chief of Aklan, Bangkaya transferred his capital to Madyanos, for strategic and economic reasons and renamed it to Laguinbanwa.

Bangkaya commissioned his two sons as officers in the government of his sakup. He appointed Balengkaka in charge of Aklan, and Balangiga for Ilayan. Balangiga had twin sons, Buean and Adlaw, from which Capiz (Kapid) was originally named, before the Spaniards came.

The center of government of the Confederation was Aklan, when Sumakwel expired and Bangkaya succeeded him as leader of Panay. Bangkaya was then replaced by Paiburong. Aklan returned to become the center of Confederation again, when Paiburong expired and was replaced by Balengkaka.

The Datus of Madja-as according to oral tradition

| The Datus | District | First Lady | Children |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datu Puti | Sinugbohan | Pinangpangan | |

| Datu Sumakwel | Malandog | Kapinangan/Alayon | 1.Omodam

2.Baslan 3.Owada 4.Tegunuko |

| Datu Bangkaya | Aklan | Katorong | Balinganga |

| Datu Paiburong | Irong-Irong (Iloilo) | Pabulangan | 1.Ilohay Tananyon

2. Ilehay Solangaon

|

| Datu Lubay | Malandog | None | |

| Datu Padohinog | Malandog | Ribongsapay | |

| Datu Dumangsil | Katalan River Taal | None | |

| Datu Dumangsol | Malandog | None | |

| Datu Balensucla | Katalan River | None |

References

- Abeto, Isidro Escare (1989). "Chapter X - Confederation of Madyaas". Philippine history: reassessed / Isidro Escare Abeto. Metro Manila :: Integrated Publishing House Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library. p. 54. OCLC 701327689.

Already conceived while he was in Binanua-an, and as the titular head of all the datus left behind by Datu Puti, Datu Sumakwel thought of some kind of system as to how he could exercise his powers given him by Datu Puti over all the other datus under his authority.

- Morrow, Paul. "The Maragtas Legend". paulmorrow.ca. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019.

In Maragtas, Monteclaro also told the story of the creation of the Confederation of Madya-as in Panay under the rule of Datu Sumakwel and he gave the details of its constitution. In spite of the importance that should be placed on such an early constitution and his detailed description of it, Monteclaro gave no source for his information. Also, it appears that the Confederation of Madya-as is unique to Monteclaro's book. It has never been documented anywhere else nor is it among the legends of the unhispanized tribes of Panay.

- Wendy Hutton (2000). Adventure Guides: East Malaysia. Tuttle Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-962-593-180-7.

- cf. Francisco Colin, S.J., Labor evangélica, Madrid:1663.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, pp. 120–121.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, p. 121.

- Cf. F. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage, Manila: 2000, p. 75.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, pp. 121-122.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, p. 122.

- Cf. Sebastian Sta. Cruz Serag, The Remnants of the Great Ilonggo Nation, Sampaloc, Manila: Rex Book Store, 1991, p. 21.

- Scott, William Henry, Pre-hispanic Source Materials for the study of Philippine History, 1984: New Day Publishers, pp. 101, 296.

- "... and because I know them better, I shall start with the island of Cebu and those adjacent to it, the Pintados. Thus I may speak more at length on matters pertaining to this island of Luzon and its neighboring islands..." BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803, Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583), p. 35.

- Cf. Maria Fuentes Gutierez, Las lenguas de Filipinas en la obra de Lorenzo Hervas y Panduro (1735-1809) in Historia cultural de la lengua española en Filipinas: ayer y hoy, Isaac Donoso Jimenez,ed., Madrid: 2012, Editorial Verbum, pp. 163-164.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, pp. 122-123.

- Cf. Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 04 of 55 (1493-1803). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 257-260.

- Francisco Colin, S.J., Labora Evangelica de los Obreros de la Campania de Jesus en las Islas Filipinas (Nueva Edicion: Illustrada con copia de notas y documentos para la critica de la Historia General de la Soberania de Espana en Filipinas, Pablo Pastells, S.J., ed.), Barcelona: 1904, Imprenta y Litografia de Henrich y Compañia, p. 31.

- The word "sakop" means "jurisdiction", and "Kinadatuan" refers to the realm of the Datu - his principality.

- William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 102 and 112

- In Panay, even at present, the landed descendants of the Principales are still referred to as Agalon or Amo by their tenants. However, the tenants are no longer called Uripon (in Karay-a, i.e., the Ilonggo sub-dialect) or Olipun (in Sinâ, i.e., Ilonggo spoken in the lowlands and cities). Instead, the tenants are now commonly referred to as Tinawo (subjects)

- William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 112- 118.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Seclusion and Veiling of Women: A Historical and Cultural Approach

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493-1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XXIX, pp. 290-291.

- William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 113.

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493-1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XXIX, p. 292.

- Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 41.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 133.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 133 and 135.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 135.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 131.

- Speaking about the theogony, i.e., genealogy of the local gods of the Visayans, the historian Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino comments on Labaodumgug (Labaw Donggon), who is in the list of these gods, saying that he "is a hero in the ancient time, who was invoked during weddings and in their songs. In Iloilo there was a rock which appear to represent an indigenous man who, with a cane, impales a boat. It was the image or the diwata himself that is being referred to". the actual words of the historian are: "Labaodumgog, heroe de su antegüedad, era invocado en sus casamientos y canciones. En Iloilo había una peña que pretendía representar un indígna que con una caña impalía un barco. Era la imágen ó il mismo dinata d que se trata." Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 42.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo, June 1582) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 121-126.

- Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, pp. 41-42.

- Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 44.

- Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, pp. 44- 45.

- Cf. Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 03 of 55 (1493-1803). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 15 - 16.

- Cf. Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 03 of 55 (1493-1803). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 73.

- Akeanon Online (Aklan History Part 4 - from Madyanos to Kalibo - 1213-1565)

- Mamuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565-1615), Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1975, pp. 374-376.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1782) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 67.

- Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 71.

- Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 9.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1782) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 69.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1782) in Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 71.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cf. William Henry Scott (1903). "Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society". (1 January 1994) pp. 109-110.

- Maragtas by Pedro Alcantara Monteclaro

- Akeanon Online (Aklan History Part 3 - Confederation of Madjaas).