Voiced retroflex lateral flap

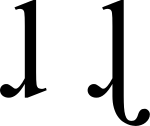

The voiced retroflex lateral flap is a type of consonantal sound, used in some spoken languages. It has no explicitly approved symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet, but may be represented as a short ⟨ɭ̆⟩, with the old dot diacritic ⟨ɺ̣⟩, or with a retroflex tail, ⟨𝼈⟩ (PUA = ⟨ɺ̢⟩ , accepted for Unicode 14).

| Voiced retroflex lateral flap | |

|---|---|

| ɭ̆ | |

| ɺ̣ | |

| 𝼈 |

Features

Features of the voiced retroflex lateral flap:

- Its manner of articulation is tap or flap, which means it is produced with a single contraction of the muscles so that one articulator (usually the tongue) is thrown against another.

- Its place of articulation is retroflex, which prototypically means it is articulated subapical (with the tip of the tongue curled up), but more generally, it means that it is postalveolar without being palatalized. That is, besides the prototypical subapical articulation, the tongue contact can be apical (pointed) or laminal (flat).

- Its phonation is voiced, which means the vocal cords vibrate during the articulation.

- It is an oral consonant, which means air is allowed to escape through the mouth only.

- It is a lateral consonant, which means it is produced by directing the airstream over the sides of the tongue, rather than down the middle.

- The airstream mechanism is pulmonic, which means it is articulated by pushing air solely with the lungs and diaphragm, as in most sounds.

Occurrence

| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwaidja | [ŋaɭ̆uli] | 'my foot' | |||

| Kannada | ಕೇಳಿ/Kēḷi | [keːɭ̆iː] | 'to ask' | Can be an approximant [ɭ] instead. | |

| Kobon | ƚawƚ | [ɭ̆awɭ̆] | 'to shoot' | Subapical. | |

| Konkani | फळ/fāḷ | [fəɭ̆] | 'fruit' | ||

| Kresh[1] | — | — | |||

| Malayalam | വേളി/vēḷi | [veːɭ̆iː] | 'marriage' | Can be an approximant [ɭ] instead. | |

| Marathi | केळी/Kēḷī | [keɭ̆iː] | 'bananas' | See Marathi phonology | |

| Tarama & Irabu[2] | — | [paɨɭ̆] | 'to pull' | ||

| Norwegian | Trøndersk[3] | glas | [ˈɡɺ̠ɑːs] | 'glass' | Apical postalveolar;[3] also described as central [ɽ].[4] See Norwegian phonology |

| O'odham[5] | — | — | Apical postalveolar.[5] | ||

| Pashto[6][7] | ړوند/llund | [ɭ̆und] | 'blind' | Contrasts plain and nasalized flaps.[6][7] Tend to be lateral at the beginning of a prosodic unit, and a central flap [ɽ] or approximant [ɻ] elsewhere. | |

| Tamil | குளி/Kuḷi | [ˈkuɭ̆i] | 'bathe' | Allophone of /ɭ/. See Tamil phonology | |

| Tarahumara | Western Rarámuri | — | — | Often transcribed /ɺ̢/.[8] | |

| Totoli[9] | — | /uɭ̆aɡ/ | 'snake' | Allophone of /ɺ/ after back vowels.[9] | |

| Tukang Besi[10] | — | — | Possible allophone of /l/ after back vowels, as well as an allophone of /r/.[10] | ||

| Wayuu | — | ɭ̆áɨɭ̆aa | 'old man' | postalveolar? | |

A retroflex lateral flap has been reported from various languages of Sulawesi such as the Sangiric languages, Buol and Totoli,[11] as well as Nambikwara in Brazil (plain and laryngealized), Gaagudju in Australia, Purépecha and Western Rarámuri in Mexico, Moro in Sudan, O'odham and Mohawk in the United States, Chaga in Tanzania, and Kanuri in Nigeria.

Various Dravidian and Indic languages of India are reported to have a retroflex lateral flap, either phonemically or phonetically, including Gujarati, Konkani, Marathi, Odia, and Rajasthani.[12] Masica describes the sound as widespread in the Indic languages of India:

A retroflex flapped lateral /ḷ/, contrasting with ordinary /l/, is a prominent feature of Odia, Marathi–Konkani, Gujarati, most varieties of Rajasthani and Bhili, Punjabi, some dialects of "Lahnda", ... most dialects of West Pahari, and Kumauni (not in the Southeastern dialect described by Apte and Pattanayak), as well as Hariyanvi and the Saharanpur subdialect of Northwestern Kauravi ("Vernacular Hindustani") investigated by Gumperz. It is absent from most other NIA languages, including most Hindi dialects, Nepali, Garhwali, Bengali, Assamese, Kashmiri and other Dardic languages (except for the Dras dialect of Shina and possibly Khowar), the westernmost West Pahari dialects bordering Dardic (Bhalesi, Khashali, Rudhari, Padari) as well as the easternmost (Jaunsari, Sirmauri), and from Sindhi, Kacchi, and Siraiki. It was once present in Sinhalese, but in the modern language has merged with /l/.[13]

Dedicated symbol

There is no explicitly approved IPA symbol for the retroflex lateral flap. However, the expected symbol may be created by combining the symbol for the alveolar lateral flap with the tail of the retroflex consonants,

This was only accepted by Unicode in 2020, and so for now normal typography requires the use of a combining diacritic, ⟨ɺ̢ ⟩. SIL International includes this symbol to the Private Use Areas of their Gentium Plus, Charis, and Doulos fonts, as U+F269 (⟨ ⟩).

References

- D. Richard Brown, 1994, "Kresh", in Kahrel & van den Berg, eds, Typological studies in negation, p 163

- Aleksandra Jarosz, 2014, "Miyako-Ryukyuan and its contribution to linguistic diversity", JournaLIPP 3, p. 43.

- Grønnum, Nina (2005), Fonetik og fonologi, Almen og Dansk (3rd ed.), Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, p. 155, ISBN 87-500-3865-6

- Heide, Eldar (2010), "Tjukk l – Retroflektert tydeleggjering av kort kvantitet. Om kvalitetskløyvinga av det gamle kvantitetssystemet.", Maal og Minne, Novus forlag, 1 (2010): 3–44

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- D.N. MacKenzie, 1990, "Pashto", in Bernard Comrie, ed, The major languages of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa, p. 103

- Herbert Penzl, 1965, A reader of Pashto, p 7

- Burgess 1984, p. 7.

- Nikolaus Himmelmann, 2001, Sourcebook on Tomini-Tolitoli languages, The Australian National University

- Donohue, Mark (1999), "Tukang Besi", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, Cambridge University Press, p. 152, ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- J. N. Sneddon, 1984, Proto-Sangiric & the Sangiric languages pp 20, 23

-

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2

- Colin Masica, The Indo-Aryan Languages, CUP, 1991, p. 97.

External links

- List of languages with [ɺ̺̠] on PHOIBLE