Keene, New Hampshire

Keene is a city in, and the seat of, Cheshire County, New Hampshire, United States.[3] The population was 23,409 at the 2010 census.[4]

Keene, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

City | |

Central Square in downtown Keene | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Elm City | |

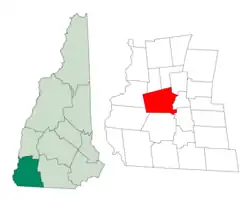

Location in Cheshire County, New Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 42°56′01″N 72°16′41″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Cheshire |

| Settled | 1736 |

| Incorporated | 1753 (town) |

| Incorporated | 1874 (city) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | George S. Hansel (R) |

| • City Council | Members

|

| • City Manager | Elizabeth A. Dragon |

| Area | |

| • Total | 37.35 sq mi (96.74 km2) |

| • Land | 37.09 sq mi (96.07 km2) |

| • Water | 0.26 sq mi (0.67 km2) 0.67% |

| Elevation | 486 ft (148 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 23,409 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 22,786 |

| • Density | 614.31/sq mi (237.18/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 03431, 03435 |

| Area code(s) | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-39300 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0867823 |

| Website | ci |

| |

Keene is home to Keene State College and Antioch University New England. It hosted the state's annual pumpkin festival from 1991 to 2014, several times setting a world record for most jack-o'-lanterns on display.

The grocery wholesaler C&S Wholesale Grocers is based in Keene.

History

In 1735 Colonial Governor Jonathan Belcher granted lots in the township of "Upper Ashuelot" to 63 settlers who paid five pounds each.[5]:21–22 Settled after 1736 on Equivalent Lands,[6] it was intended to be a fort town protecting the Province of Massachusetts Bay from the French and their Native allies during the French and Indian Wars, the North American front of the Seven Years' War. When the boundary between the Massachusetts Bay and New Hampshire colonies was fixed in 1741, Upper Ashuelot became part of New Hampshire, although Massachusetts continued supporting the area for its own protection.

In 1747, during King George's War, the village was attacked and burned by Natives.[5]:79 Colonists fled to safety, but would return to rebuild in 1749.[5]:96 It was regranted to its inhabitants in 1753 by Governor Benning Wentworth, who renamed it "Keene" after Sir Benjamin Keene,[7] English minister to Spain and a West Indies trader. Located at the center of Cheshire County, Keene was designated as the county seat in 1769. Land was set off for the towns of Sullivan and Roxbury, although Keene would annex 154 acres (0.62 km2) from Swanzey (formerly Lower Ashuelot).

Timothy Dwight, the Yale president who chronicled his travels, described the town as "...one of the prettiest in New England." Situated on an ancient lake bed surrounded by hills, the valley with fertile meadows was excellent for farming. The Ashuelot River was later used to provided water power for sawmills, gristmills and tanneries. After the railroad was constructed to the town in 1848, numerous other industries were established. Keene became a manufacturing center for wooden-ware, pails, chairs, sashes, shutters, doors, pottery, glass, soap, woolen textiles, shoes, saddles, mowing machines, carriages and sleighs. It also had a brickyard and foundry. Keene was incorporated as a city in 1874, and by 1880 had a population of 6,784. In the early 1900s, the Newburyport Silver Company moved to Keene to take advantage of its skilled workers and location.

New England manufacturing declined in the 20th century, however, particularly during the Great Depression. Keene is today a center for insurance, education, and tourism. The city retains a considerable inventory of fine Victorian architecture from its mill town era. An example is the Keene Public Library, which occupies a Second Empire mansion built about 1869 by manufacturer Henry Colony.

Keene's manufacturing success was brought on in part by its importance as a railroad city. The Cheshire Railroad, Manchester & Keene Railroad, and the Ashuelot Railroad all met here. By the early 1900s all had been absorbed by the Boston & Maine Railroad. Keene was home to a railroad shop complex and two railroad yards. The Manchester & Keene Branch was abandoned following the floods of 1936. Beginning in 1945, Keene was a stopping point for the Boston & Maine's streamlined trainset known at that time as the Cheshire.

Keene became notable in 1962 when F. Nelson Blount chose the city for the site of his Steamtown, U.S.A. attraction. But Blount's plan fell through and, after one operating season in Keene, the museum was relocated to nearby Bellows Falls, Vermont. The Boston & Maine abandoned the Cheshire Branch in 1972, leaving the Ashuelot Branch as Keene's only rail connection to the outside world.

In 1978 the B&M leased switching operations in Keene to the Green Mountain Railroad, which took over the entire Ashuelot Branch in 1982. Passenger decline and track conditions forced the Green Mountain to end service on the Ashuelot Branch in 1983 and return operating rights to the B&M. However, there were no longer enough customers to warrant service on the line. In 1984 the last train arrived in and departed Keene, consisting of Boston & Maine EMD GP9 1714, pulling flat cars to carry rails removed from the railyard. Track conditions on the Ashuelot Branch were so poor at the time that the engine returned light (without cars) to Brattleboro. A hi-rail truck was used instead to remove the flatcars.

In 1995 the freight house, one of the last remaining railroad buildings in town, burned due to arson. Since the late 20th century, the railroad beds through town were redeveloped as the Cheshire Rail Trail and the Ashuelot Rail Trail.

In 2011, radical activist Thomas Ball immolated himself on the steps of a courthouse in Keene to protest what he considered the court system's abuse of divorced fathers' rights.[8]

Geography

Keene is located at 42°56′01″N 72°16′41″W (42.9339, −72.2784).[9]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 37.5 square miles (97.1 km2), of which 37.3 square miles (96.5 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.7 km2) is water, the latter comprising 0.67% of the town.[4] Keene is drained by the Ashuelot River. The highest point in Keene is the summit of Grays Hill in the city's northwest corner, at 1,388 feet (423 m) above sea level. Keene is entirely within the Connecticut River watershed, with all of the city except for the northwest corner draining to the Connecticut via the Ashuelot.[10]

State highways converge on Keene from nine directions. New Hampshire Route 9 leads northeast to Concord, the state capital, and west to Brattleboro, Vermont. Route 10 leads north to Newport and southwest to Northfield, Massachusetts. Route 12 leads northwest to Walpole and Charlestown and southeast to Winchendon, Massachusetts. Route 101 leads east to Peterborough and Manchester, Route 32 leads south to Swanzey, then to Athol, Massachusetts, and Route 12A leads north to Surry and Alstead. A limited-access bypass used variously by Routes 9, 10, 12, and 101 passes around the north, west, and south sides of downtown.

Keene is served by Dillant–Hopkins Airport, located just south of the city in Swanzey.[11]

Climate

Keene is located in a humid continental climate zone.[12] It experiences all four seasons quite distinctly. The average high temperature in July is 82 °F (28 °C), and the record high for Keene is 102 °F (39 °C). As with other cities in the eastern U.S., periods of high humidity can raise heat indices to near 110 °F (43 °C). During the summer, Keene can get hit by thunderstorms from the west, but the Green Mountains to the west often break up some of the storms, so that Keene doesn't usually experience a thunderstorm at full strength. The last time a tornado hit Cheshire County was in 1997.

The winters in Keene can be very harsh. The most recent such winter was 2002–2003, when Keene received 112.5 inches (2,860 mm) of snow. The majority of the snowfall in Keene comes from nor'easters, areas of low pressure that move up the Atlantic coast and strengthen. Many times these storms can produce blizzard conditions across southern New England. Recent examples are the blizzard of 2005 and the blizzard of 2006. Keene is situated in an area where cold air meets the moisture from the south, so often Keene gets the jackpot with winter storms. Aside from snow, winters can be very cold. Even in the warmest of winters, Keene usually has at least one night below 0 °F (−18 °C). During January 2004, Keene saw highs below freezing 25 of the days, including five days in the single digits and one day with a high of zero. Overnight lows dropped below zero 12 times, including 7 nights below −10 °F (−23 °C). The record low in Keene is −31 °F (−35 °C). In addition to the cold temperatures, Keene can receive biting winds that drive the wind chill down below −30 °F (−34 °C).

Snow can occur right through the end of April, but on the other end, 80 °F (27 °C) days can begin in late March. Autumn weather is similar. Keene's first snowfall usually occurs in early November, though the city can also see 60 °F (16 °C) days into mid-November. Significant rain events can occur in the spring and fall. For example, record rainfall and flooding with the axis of heaviest rain (around 12 inches (300 mm)) near Keene occurred in October 2005. Another significant flood event occurred in May of the following year.

Climate chart

| Climate data for Keene, New Hampshire | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.2 (0.1) |

35.6 (2.0) |

45.3 (7.4) |

58.6 (14.8) |

71.2 (21.8) |

79.2 (26.2) |

83.8 (28.8) |

81.5 (27.5) |

73.4 (23.0) |

62.4 (16.9) |

48.6 (9.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

58.9 (15.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 9.9 (−12.3) |

12.6 (−10.8) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

32.9 (0.5) |

43.5 (6.4) |

52.7 (11.5) |

57.4 (14.1) |

55.9 (13.3) |

47.8 (8.8) |

37.2 (2.9) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

35.0 (1.6) |

| Source: [13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 1,314 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,645 | 25.2% | |

| 1810 | 1,646 | 0.1% | |

| 1820 | 1,895 | 15.1% | |

| 1830 | 2,374 | 25.3% | |

| 1840 | 2,610 | 9.9% | |

| 1850 | 3,392 | 30.0% | |

| 1860 | 4,320 | 27.4% | |

| 1870 | 5,971 | 38.2% | |

| 1880 | 6,784 | 13.6% | |

| 1890 | 7,446 | 9.8% | |

| 1900 | 9,165 | 23.1% | |

| 1910 | 10,068 | 9.9% | |

| 1920 | 11,210 | 11.3% | |

| 1930 | 13,794 | 23.1% | |

| 1940 | 13,832 | 0.3% | |

| 1950 | 15,638 | 13.1% | |

| 1960 | 17,562 | 12.3% | |

| 1970 | 20,467 | 16.5% | |

| 1980 | 21,449 | 4.8% | |

| 1990 | 22,430 | 4.6% | |

| 2000 | 22,955 | 2.3% | |

| 2010 | 23,409 | 2.0% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 22,786 | [2] | −2.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 23,409 people, 9,052 households, and 4,843 families residing in the city. The population density was 627.6 people per square mile (242.3/km2). There were 9,719 housing units at an average density of 260.6 per square mile (100.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.3% White, 0.6% African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.0% Asian, 0.004% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 0.5% some other race, and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.6% of the population.[15]

There were 9,052 households, out of which 23.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.1% were headed by married couples living together, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.5% were non-families. 31.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.6% consisted of someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26, and the average family size was 2.83.[15]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 16.6% under the age of 18, 24.1% from 18 to 24, 20.6% from 25 to 44, 24.0% from 45 to 64, and 14.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34.0 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.8 males.[15]

For the period 2010 through 2014, the estimated median income for a household in the city was $52,327, and the median income for a family was $75,057. Male full-time workers had a median income of $50,025 versus $39,818 for females. The per capita income for the city was $29,366. About 6.7% of families and 16.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.5% of those under age 18 and 11.5% of those age 65 or over.[16]

Government

| Year | GOP | DEM | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 30.36% 3,831 | 62.87% 7,932 | 6.77% 854 |

| 2012 | 28.72% 3,613 | 69.31% 8,718 | 1.97% 248 |

| 2008 | 27.60% 3,641 | 71.45% 9,427 | 0.95% 126 |

| 2004 | 32.08% 4,004 | 67.12% 8,378 | 0.81% 101 |

| 2000 | 36.29% 3,704 | 57.37% 5,856 | 6.34% 647 |

| 1996 | 32.14% 2,910 | 59.66% 5,401 | 8.20% 742 |

| 1992 | 31.79% 3,257 | 50.85% 5,210 | 17.36% 1,779 |

Keene's government consists of a mayor and a city council which has 15 members. Two are elected from each of the city's five wards, and five councilors are elected at-large.[18]

In the New Hampshire Senate, Keene is included in the 10th District and is represented by Democrat Jay Kahn. On the New Hampshire Executive Council, Keene is in the 2nd District and is represented by Democrat Andru Volinsky. In the United States House of Representatives, Keene is a part of New Hampshire's 2nd Congressional District and is currently represented by Democrat Ann McLane Kuster.

Keene is a strongly Democratic-leaning city at the presidential level, as no Republican presidential nominee has carried the city in over two decades.

Media

Several media sources are located in Keene. These include:

Print

- The Keene Sentinel

- The Monadnock Shopper News

- The Equinox, student newspaper of Keene State College

- Parent Express

- FPP News

Radio

The city has several radio stations licensed by the FCC to Keene. The stations are:

- AM

- FM

- WEVN 90.7, operated by New Hampshire Public Radio[20]

- WKNH 91.3, operated by Keene State College[21]

- WKHP-LP 94.9, a low power FM operated by the Keene FourSquare church[22]

- WSNI 97.7 (Adult Contemporary, Sunny 97). WSNI changed its city of license from Swanzey to Keene in September 2009.[23]

- W256BJ 99.1, (Adult Album Alternative, "The River", //WKNE-HD2)[19][24]

- W276CB 103.1, (Oldies, "Oldies 103.1", //WKNE-HD3)[19][25]

- WKNE 103.7 (Hot Adult Contemporary, 1037 KNE FM)

- Syndicated programming

- Free Talk Live, nationally syndicated radio talk show based in Keene

- Radical Agenda, nationally syndicated radio talk show based in Keene

Television

- Cheshire TV, local cable programming[26]

- WEKW-TV (Digital 48/Virtual 52), New Hampshire Public Television affiliate (PBS)[27][28]

- When Elderly Attack (season 8)

Keene is part of the Boston television market.[29] Time Warner Cable is the major supplier of cable television programming for Keene. Local stations offered on Time Warner include most major Boston-area and New Hampshire stations (including WEKW), as well as WVTA, the Vermont PBS outlet in Windsor, Vermont.

Education

Keene is often considered a minor college town, as it is the site of Keene State College, whose 5,400 students make up over ¼ of the city's population, and Antioch University New England.

At the secondary level, Keene serves as the educational nexus of the area, due in large part to its status as the largest community of Cheshire County. Keene High School is the largest regional High School in Cheshire County, serving about 1,850 students.

Keene has one middle school, Keene Middle School, and four elementary schools, as of 2014: Fuller Elementary School, Franklin Elementary School, Symonds Elementary School, Wheelock Elementary School. Jonathan Daniels was downsized to only pre-school and administration offices.

Keene is part of New Hampshire's School Administrative Unit 29, or SAU 29.

Culture

Religion

Keene has more than 20 churches, mostly Protestant, and one synagogue, Congregation Ahavas Achim. A significant landmark in downtown Keene is the United Church of Christ at Central Square, colloquially known in town as the "White Church" or the "Church at the Head of the Square". A second church on the square was Grace United Methodist Church, also known as the "Brick Church", but it is now privately owned and operated for secular purposes. The Grace United Methodist congregation moved to another site.

Keene is the seat of the Roman Catholic Parish of the Holy Spirit, whose pastor is the Dean of the Monadnock Deanery, a division under the see of the Diocese of Manchester. The parish has two churches in the City of Keene, Saint Bernard and Saint Margaret Mary. Keene has one Episcopal church, Saint James, which is within the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire. Keene also has one Greek Orthodox church, Saint George, which is under the see of the Metropolis of Boston.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints building is home to the Keene Ward and is part of the Nashua, New Hampshire Stake.

Pumpkin Festival

Every October from 1991 to 2014, Keene hosted an annual pumpkin festival called the Keene Pumpkin Festival, locally known as Pumpkin Fest. The event set world records several times for the largest simultaneous number of jack-o'-lanterns on display. The first time was in 1993, when Keene set the record with nearly 5,000 carved and lit pumpkins.[30] The tally from the 2003 festival stood as the record until Boston took the lead in 2006, but Keene reclaimed the world record in 2013, with a total of 30,581 pumpkins, according to Guinness World Records.[31] Besides the pumpkins stacked on massive towers set in the streets, thousands of additional pumpkins were installed along the streets of the city. Face painting, fireworks, music, and other entertainments were also provided.

After riots from college students (the majority of which were not associated with Keene State and were in attendance due to the publicity of the 2013 festival) nearby to the 2014 event location, the Keene Pumpkin Festival [32] was moved to Laconia the following year and renamed as the New Hampshire Pumpkin Festival.[33] From 2017 onward (except for 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New Hampshire), the organizers of the 2011 through 2014 Keene Pumpkin Festivals, along with the 2015 New Hampshire Pumpkin Festival in Laconia, have run a new smaller, child-focused Keene Pumpkin Festival with a number of restrictions in place, promoting it as the "official" continuation of the Keene Pumpkin Festival.[34][35]

Keene Music Festival

In late August or early September the city hosts the Keene Music Festival. Several stages are located throughout the downtown area during the day's events, which are free to the public and sponsored by locally owned businesses. Visitors, mostly from the local community, roam the city's sidewalks listening to the dozens of bands.

Keene in popular culture

- The 1949 movie Lost Boundaries, starring Mel Ferrer, tells the true story of a black Keene physician who passed as white for many years. The film won the 1949 Cannes Film Festival award for best screenplay.

- Much of the 1995 movie Jumanji, starring Robin Williams, was filmed in Keene in November 1994, as the movie's fictional town of Brantford. Frank's Barber Shop is a featured setting as well as the Parrish Shoe sign, which was painted for the film. The sign served as a focal point for a temporary Robin Williams memorial in the days following the actor's death on August 11, 2014.

Music and theatre

In 1979, First Lady Rosalynn Carter dedicated the bandstand in Central Square as the E. E. Bagley Bandstand, after the noted composer of the National Emblem March, who made Keene his home until his death in 1922.[36]

Many community groups perform on a regular basis, including the Keene Chamber Orchestra, the Keene Chamber Singers, the Keene Chorale, the Greater Keene Pops Choir, and the Keene Jazz Orchestra.

The Cheshiremen Chorus, a local chapter of the Barbershop Harmony Society, meet every Tuesday at 6:30 pm at the Hannah Grimes Center at 25 Roxbury Street.

The Monadnock Pathway Singers are an all-volunteer hospice group based in Keene whose members come from many different towns within Cheshire County. They sing in nursing homes, hospitals, assisted-living centers and in private homes throughout Cheshire County.

Every year, the Keene branch of the Lions Clubs International performs a Broadway musical at the Colonial Theatre (a restored theatre dating back to 1924), to raise money for the community. Other theatres and auditoriums include the new Keene High School Auditorium and the county's largest auditorium, the Larracey Auditorium at Keene Middle School, and The Putnam Arts Lecture Hall on the campus of Keene State. Keene Cinemas is the local movie theater located off of Key Road.

Sports

Keene is home to the Keene Swamp Bats baseball team of the New England Collegiate Baseball League (NECBL). The Swamp Bats play at Alumni Field in Keene during June and July of each summer. The Swamp Bats are five-time league champions (2000, 2003, 2011, 2013, and 2019). They are consistently at the top of the NECBL in attendance, having led the league in 2002, 2004, and 2005.

The Elm City Derby Damez roller derby league, members of USA Roller Sports (USARS), call Keene home while playing their officially sanctioned bouts in nearby Brattleboro, Vermont. They compete against many other women's flat track leagues around the northeastern United States.

The Monadnock Wolfpack Rugby Football Club now calls Keene its home. They play in NERFU (New England Rugby Football Union) division IV at Carpenter Field, on Carpenter Street. They will defend their undefeated championship 2018 season in the Fall of 2019.

Images

Stone Arch Bridge c. 1906

Stone Arch Bridge c. 1906 Griffin Estate c. 1908

Griffin Estate c. 1908 Central Square in 1907

Central Square in 1907 West Street in 1910

West Street in 1910

Free Keene

The city has become home to an active voluntaryist protest group known as Free Keene, which is associated with the Free State Project.[37][38] Some Free Keene activists have been arrested for video recording in courtrooms as an act of civil disobedience, in violation of the state's wiretapping law. In 2009, Keene's Central Square Park had become the center of daily 4:20 pm smoke-ins which advocated the legalization of marijuana.[39][40][41]

Free Keene has encountered opposition from other Keene residents.[37][42] While some of the activists' techniques can be relatively confrontational, and the WMUR report mentioned a tongue-in-cheek drinking party at a government building to protest open-container laws, others are significantly less so. For example, a common act by some Free Keene activists involves paying money into expired parking meters to help other citizens avoid parking tickets, which has created conflict between the meter pluggers and the parking enforcement officers. The close encounters with the "Robin Hooders" resulted in one PEO resigning his position and a lawsuit filed by the City of Keene citing harassment of their employees.[43] In December 2013, the judge overseeing the case dismissed the city's arguments against the "Robin Hooders" on first amendment grounds, citing the public sidewalks' role as a traditional public forum.[44]

In November 2014, the group was lampooned in an episode of The Colbert Report. The segment focused mainly on the poor treatment by "Robin Hooders" of the parking enforcement officers.[45]

Sites of interest

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

Notable people

- Adam "Adeem" Arnone (b. 1978), best known for his work in the hip hop group Glue and for winning the Scribble Jam Emcee Battle in 1998 and 2001

- Edwin Eugene Bagley (1857–1922), composer

- John Bosa (b. 1964), defensive lineman with the Miami Dolphins[47]

- Francis B. Brewer (1820–1892), U.S. congressman from New York[48]

- Christopher Cantwell (b. 1980), white nationalist[49]

- Jimmy Cochran (b. 1981), Olympic alpine skier[50]

- Richard B. Cohen (b. 1952), American billionaire, sole owner of C&S Wholesale Grocers

- Jonathan Daniels (1939–1965), activist murdered during the Civil Rights Movement[51]

- Clarence DeMar (1888–1958), seven-time Boston Marathon champion[52]

- John Dickson (1783–1852), U.S. congressman from New York[53]

- Samuel Dinsmoor, fourteenth Governor of New Hampshire[54]

- Michael Dubruiel (1958–2009), Catholic author

- Eva Fabian (born 1993), American-Israeli world champion swimmer [55]

- Barry Faulkner (1881–1966), muralist[56]

- Tessa Gobbo (b. 1990), two-time world champion rower, Olympic gold medalist in the women's eight

- Mary Whitwell Hale (1810–1862), founded a school in Keene

- Salma Hale (1787–1866), U.S. congressman from New Hampshire[57]

- Samuel W. Hale, member of the New Hampshire House of Representatives and the 39th Governor of New Hampshire[58]

- Ernest Hebert (b. 1941), author[59]

- JoJo (b. 1990), singer

- A.G. Lafley, led consumer goods maker Procter & Gamble (P&G) for two separate stints, from 2000 to 2010 and again from 2013 to 2015

- Martha Perry Lowe (1829–1902), poet[60]

- David G. Perkins (b. 1958), U.S. Army general[61]

- Terry Pindell, travel writer[62]

- Robert Rodat, film and television writer

- Mary Elizabeth Wilson Sherwood (1830–1903), author and socialite

- Duncan Watson (b. 1963), former child actor[63][64]

- Heather Wilson (b. 1960), U.S. Secretary of the Air Force, former U.S. congresswoman from New Mexico[65]

- Isaac Wyman (1724–1792), Revolutionary era soldier and judge[66]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "NACo County Explorer". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Keene city, New Hampshire". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- Griffin, Simon Goodell; Whitcomb, Frank H.; Applegate (Jr.), Octavius (1904). A History of the Town of Keene: From 1732, when the Township was Granted by Massachusetts, to 1874, when it Became a City. Keene, N.H.: Sentinel Printing Company. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

No charter was granted by Massachusetts. The title rested in the acts of the legislature and the compliance with those acts by the payment of five pounds by each grantee, for himself and his heirs, and the fulfillment of all the conditions of the grant. Under that title these sixty-three grantees owned all the land in the township. The house-lots were laid out by the committee of the legislature, to be drawn by lot, and these proprietors and their successors divided the remainder of the land among themselves from time to time, as will be seen by their records.

- Equivalent Lands; webpage; Vermont History on-line; accessed April 26, 2020

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 173.

- Arsenault, Mark (July 10, 2011). "Dad leaves clues to his desperation". Boston Globe. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Keene". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey.

- "Keene Dillant Hopkins Airport EEN | City of Keene". ci.keene.nh.us. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- "Keene, Nh Climate Keene, Nh Temperatures Keene, Nh Weather Averages". keene.climatemps.com. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- "Keene, NH, New Hampshire, United States: Climate, Global Warming, and Daylight Charts and Data". Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1): Keene city, New Hampshire". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2010-2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (DP03): Keene city, New Hampshire". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- http://sos.nh.gov/ElectResults.aspx

- "City Council". City of Keene. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "CDBS Print". licensing.fcc.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "New Hampshire Public Radio". nhpr.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "FCCInfo Facility Search Results". fccinfo.com. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "FCCInfo Facility Search Results". fccinfo.com. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "Application Search Details". licensing.fcc.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "Homepage – Keene Classics 99.1 – WKNE-HD2". keeneclassics.com. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "Homepage – WKNE-HD3 – Saga". kool1031.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "Cheshire TV". cheshiretv.org. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "FCCInfo Results". fccinfo.com. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "What's On – Main TV Schedule – NHPTV". nhptv.org. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- Per Zap2it, zip code 03431.

- "Keene, NH tops Boston's world record with 30,581 jack-o'-lanterns". Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- "Most lit jack-o'-lanterns displayed". Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sexton, Adam (April 24, 2015). "It's official: Laconia will host this year's pumpkin festival". WMUR-TV. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Let it Shine, Inc. "Let it Shine Pumpkin Festival". Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

Let it Shine, Inc., Nonprofit organizers of Pumpkin Festival 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2017

- Cuno-Booth, Paul (October 30, 2017). "Scaled-down version of Keene's pumpkin festival a hit with many Sunday". Sentinel Source. Keene Sentinel. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 4, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Morales, Andrea (May 4, 2014). "Libertarians Trail Meter Readers, Telling Town: Live Free or Else". New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- Free Keene website

- "Pot Smokers In Keene Protest Drug Laws". WMUR-TV News 9. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- "4:20 Cannabis Celebration Makes Sentinel Front Page Again!". Free Keene. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Schlessinger, James B. "The Growth Operation for Freedom". Cannabis Culture. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- "Is Keene Turning Into a Battleground for Activists, Police?". WMUR-TV News 9. February 21, 2011. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011.

- "'Robin Hooders' face lawsuit for plugging parking meters". WHDH-TV News 7. May 14, 2013. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013.

- Judge Cites First Amendment in Dismissing Keene Case

- The Colbert Report ~ Difference Makers - The Free Keene Squad

- "Partner City Committee". City of Keene. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- "John Bosa". Pro-Football Reference.com. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Francis B. Brewer". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Landen, Xander; Whitmore, Steven (August 16, 2017). "White nationalist from Keene claims there is a warrant out for his arrest". SentinelSource.com.

- "Vermont has strong presence on U.S. Ski Team". Stowe Today. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- "Jonathan Daniels". Alabama Humanities Foundation. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- "The Story of Clarence DeMar". Clarence DeMar Marathon. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "John Dickson". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- "DINSMOOR, Samuel, (1766 - 1835)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- "Eva Fabian". Team USA. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "Barry Faulkner". New Hampshire Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- "Salma Hale". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ""Memorial of Samuel Whitney Hale, Keene, N.H. Born April 2, 1822; died October 16, 1891". Internet Archive. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- "Ernest Hebert". upne.com. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore, Mary Ashton Rice (1893). A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life. Moulton. pp. 475–. ISBN 9780722217139.

- "David G. Perkins". kansascity.com. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- "Terry Pindell | Authors | Macmillan". US Macmillan. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Harrington, Blair Alexis (October 26, 2005). "Keene's Duncan Watson sees recycling as business". The Keene Sentinel.

- "Board of Trustees". Nrra.net.

- "Heather Wilson". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- "Isaac Wyman". http://files.usgwarchives.net/. Retrieved January 7, 2014. External link in

|publisher=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keene, New Hampshire. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Keene, New Hampshire. |

- City of Keene official website

- DowntownKeene.com

- Keene Public Library

- New Hampshire Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau Profile

- Historical Society of Cheshire County

- "Upper Ashuelot: a history of Keene NH" (entire book in pdf format)

- "A History of the Town of Keene from 1732...to 1874" by S.Griffin

- Historical Society of Cheshire County: Keene, New Hampshire: 1890–1930

- Historical Society of Cheshire County: Josiah Fisher Killed By Indians in Keene