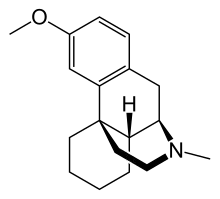

Levomethorphan

Levomethorphan (INN, BAN) is an opioid analgesic of the morphinan family that has never been marketed.[1] It is the L-stereoisomer of racemethorphan (methorphan).[1] The effects of the two isomers of the racemethorphan are quite different, with dextromethorphan (DXM) being an antitussive at low doses and a dissociative hallucinogen at much higher doses.[2] Levomethorphan is about five times stronger than morphine. [3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 3-6 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.320 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H25NO |

| Molar mass | 271.404 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Levomethorphan is a prodrug to levorphanol, analogously to DXM acting as a prodrug to dextrorphan or codeine behaving as a prodrug to morphine.[4] As such, levomethorphan has similar effects to levorphanol but is less potent as it must be demethylated to the active form by liver enzymes before being able to produce its effects.[4] As a prodrug of levorphanol, levomethorphan functions as a potent agonist of all three of the opioid receptors, μ, κ (κ1 and κ3 but notably not κ2), and δ, as an NMDA receptor antagonist, and as a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.[4] Via activation of the KOR, levomethorphan can produce dysphoria and psychotomimetic effects such as dissociation and hallucinations.[5]

Levomethorphan is listed under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961 and is regulated like morphine in most countries. In the United States it is a Schedule II Narcotic controlled substance with a DEA ACSCN of 9210 and 2014 annual aggregate manufacturing quota of 195 grams, up from 6 grams the year before. The salts in use are the tartrate (free base conversion ratio 0.644) and hydrobromide (0.958).[6] At the current time, no levomethorphan pharmaceuticals are marketed in the United States.

See also

References

- Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springe. pp. 656–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Hornback JM (31 January 2005). Organic Chemistry. Cengage Learning. pp. 243–. ISBN 0-534-38951-1.

- Wainer IW (1996). "Toxicology Through a Looking Glass: Stereochemical Questions and Some Answers". In Wong SH, Sunshine I (eds.). Handbook of Analytical Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Toxicology. CRC Press. ISBN 9780849326486.

- Gudin J, Fudin J, Nalamachu S (January 2016). "Levorphanol use: past, present and future". Postgraduate Medicine. 128 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1080/00325481.2016.1128308. PMID 26635068. S2CID 3912175.

- Bruera ED, Portenoy RK (12 October 2009). Cancer Pain: Assessment and Management. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-0-521-87927-9.

- "Conversion Factors for Controlled Substances". DEA Diversion Control Division. U.S. Department Of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

| Psychedelics (5-HT2A agonists) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociatives (NMDAR antagonists) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deliriants (mAChR antagonists) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opioids |

| ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol-type |

| ||||||||||||||||

| NSAIDs |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Cannabinoids | |||||||||||||||||

| Ion channel modulators |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Myorelaxants | |||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||