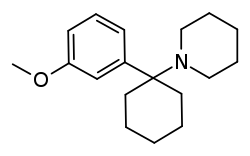

3-MeO-PCP

3-Methoxyphencyclidine (3-MeO-PCP) is a dissociative hallucinogen of the arylcyclohexylamine class related to phencyclidine (PCP) which has been sold online as a designer drug.[1][2][3] It acts mainly as an NMDA receptor antagonist, though it has also been found to interact with the sigma σ1 receptor and the serotonin transporter.[2][3] The drug does not possess any opioid activity nor does it act as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor.[1][2][3]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H27NO |

| Molar mass | 273.420 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Pharmacology

3-MeO-PCP has a Ki of 20 nM for the dizocilpine (MK-801) site of the NMDA receptor, 216 nM for the serotonin transporter (SERT), and 42 nM for the sigma σ1 receptor.[3][2] It does not bind to the norepinephrine or dopamine transporter nor to the sigma σ2 receptor (Ki >10,000 nM).[2] Based on its structural similarity to 3-hydroxy-PCP (3-HO-PCP), which uniquely among arylcyclohexylamines has high affinity for the μ-opioid receptor in addition to the NMDA receptor, it was initially expected that 3-MeO-PCP would have opioid activity.[1][4] However, radioligand binding assays with human proteins have shown that, contrary to common belief, the drug also does not interact with the μ-, δ-, or κ-opioid receptors at concentrations of up to 10,000 nM.[2] As such, the notion that 3-MeO-PCP has opioid activity has been described as a myth.[1]

3-MeO-PCP binds to the NMDA receptor with higher affinity than PCP and has the highest affinity of the three isomeric anisyl-substitutions of PCP, followed by 2-MeO-PCP and 4-MeO-PCP.[2][3]

Chemistry

3-MeO-PCP hydrochloride is a white crystalline solid with a melting point of 204–205 °C.[5]

History

3-MeO-PCP was first synthesized in 1979 to investigate the structure–activity relationships of phencyclidine (PCP) derivatives. The effects of 3-MeO-PCP in humans were not described until 1999 when a chemist using the pseudonym John Q. Beagle wrote that 3-MeO-PCP was qualitatively similar to PCP with comparable potency.[6] 3-MeO-PCP was preceded by the less potent dissociative 4-MeO-PCP and first became available as a research chemical in 2011.[6]

Society and culture

United Kingdom

On October 18, 2012 the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs in the United Kingdom released a report about methoxetamine, saying that the "harms of methoxetamine are commensurate with Class B of the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971)".[7] The report went on to suggest that all analogues of MXE should also become class B drugs and suggested a catch-all clause covering both existing and unresearched arylcyclohexylamines, including 3-MeO-PCP.[3]

United States

3-MeO-PCP is not a controlled substance in the United States but possession or distribution of 3-MeO-PCP for human use could potentially be prosecuted under the Federal Analogue Act due to its structural and pharmacological similarities to PCP.

Sweden

Sweden's public health agency suggested classifying 3-MeO-PCP as hazardous substance on November 10, 2014.[8]

Czech Republic

3-MeO-PCP is banned in the Czech Republic.[9]

Chile

As per Chile's Ley de drogas, aka Ley 20000,[10] all esters and ethers of PCP are illegal. As 3-MeO-PCP is an ether of PCP, it is thus illegal.

See also

References

- Morris H, Wallach J (2014). "From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Test Anal. 6 (7–8): 614–32. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- Roth BL, Gibbons S, Arunotayanun W, Huang XP, Setola V, Treble R, Iversen L (2013). "The ketamine analogue methoxetamine and 3- and 4-methoxy analogues of phencyclidine are high affinity and selective ligands for the glutamate NMDA receptor". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e59334. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059334. PMC 3602154. PMID 23527166.

- "(ACMD) Methoxetamine Report (2012)" (PDF). UK Home Office. 2012-10-18. p. 14. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- Morris, H. (2011-02-11). "Interview with a ketamine chemist: or to be more precise, an arylcyclohexylamine chemist". Vice Magazine. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- Wallach J, De Paoli G, Adejare A, Brandt S (2013). "Preparation and analytical characterization of 1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl)piperidine (PCP) and 1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl)pyrrolidine (PCPy) analogues". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 633–650. doi:10.1002/dta.1468. PMID 23554350.

- Morris, H.; Wallach, J. (2014). "From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 614–632. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- "Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) Methoxetamine report, 2012". Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. 18 October 2012.

- "Cannabinoider föreslås bli klassade som hälsofarlig vara". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Látky, o které byl doplněn seznam č. 4 psychotropních látek (příloha č. 4 k nařízení vlády č. 463/2013 Sb.)" (PDF) (in Czech). Ministerstvo zdravotnictví.

- "SUSTITUYE LA LEY Nº 19.366, QUE SANCIONA EL TRAFICO ILICITO DE ESTUPEFACIENTES Y SUSTANCIAS SICOTROPICAS" (in Spanish). Bibloteca Del Congreso Nacional. 22 October 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "Legislação de Combate à Droga, Tabela II-A"