Lock Haven, Pennsylvania

Lock Haven is the county seat of Clinton County, in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. Located near the confluence of the West Branch Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek, it is the principal city of the Lock Haven Micropolitan Statistical Area, itself part of the Williamsport–Lock Haven combined statistical area. At the 2010 census, Lock Haven's population was 9,772.

Lock Haven, Pennsylvania | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within Clinton County | |

Lock Haven Location within Pennsylvania  Lock Haven Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 41°08′16″N 77°27′03″W[2] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Clinton County |

| Settled | 1769 |

| Incorporated (borough) | 1844 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1870 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Joel Long |

| • Manager | Gregory J. Wilson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.67 sq mi (6.91 km2) |

| • Land | 2.50 sq mi (6.47 km2) |

| • Water | 0.17 sq mi (0.44 km2) 6.44% |

| Elevation | 561 ft (171 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 9,772 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 9,083 |

| • Density | 3,639.02/sq mi (1,404.80/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 17745 |

| Area code(s) | 570 and 272 (570 Exchanges: 484,488,893) |

| FIPS code | 42-44128 |

| Website | lockhavenpa |

Built on a site long favored by pre-Columbian peoples, Lock Haven began in 1833 as a timber town and a haven for loggers, boatmen, and other travelers on the river or the West Branch Canal. Resource extraction and efficient transportation financed much of the city's growth through the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century, a light-aircraft factory, a college, and a paper mill, along with many smaller enterprises, drove the economy. Frequent floods, especially in 1972, damaged local industry and led to a high rate of unemployment in the 1980s.

The city has three sites on the National Register of Historic Places—Memorial Park Site, a significant pre-Columbian archaeological find; Heisey House, a Victorian-era museum; and Water Street District, an area with a mix of 19th- and 20th-century architecture. A levee, completed in 1995, protects the city from further flooding. While industry remains important to the city, about a third of Lock Haven's workforce is employed in education, health care, or social services.

History

Pre-European

The earliest settlers in Pennsylvania arrived from Asia between 12000 BCE and 8000 BCE, when the glaciers of the Pleistocene Ice Age were receding. Fluted point spearheads from this era, known as the Paleo-Indian Period, have been found in most parts of the state.[6] Archeological discoveries at the Memorial Park Site 36Cn164 near the confluence of the West Branch Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek collectively span about 8,000 years and represent every major prehistoric period from the Middle Archaic to the Late Woodland period.[7] Prehistoric cultural periods over that span included the Middle Archaic starting at 6500 BCE; the Late Archaic starting at 3000 BCE; the Early Woodland starting at 1000 BCE; the Middle Woodland starting at 0 CE; and the Late Woodland starting at 900 CE.[8] First contact with Europeans occurred in Pennsylvania between 1500 and 1600 CE.[8][9]

Eighteenth century

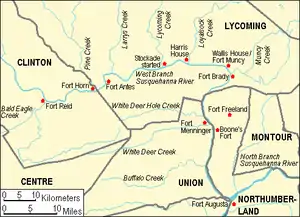

In the early 18th century, a tribal confederacy known as the Six Nations of the Iroquois, headquartered in New York, ruled the Indian (Native American) tribes of Pennsylvania, including those who lived near what would become Lock Haven. Indian settlements in the area included three Munsee villages on the 325-acre (1.32 km2) Great Island in the West Branch Susquehanna River at the mouth of Bald Eagle Creek. Four Indian trails, the Great Island Path, the Great Shamokin Path, the Bald Eagle Creek Path, and the Sinnemahoning Path, crossed the island, and a fifth, Logan's Path, met Bald Eagle Creek Path a few miles upstream near the mouth of Fishing Creek.[10] During the French and Indian War (1754–63), colonial militiamen on the Kittanning Expedition destroyed Munsee property on the Great Island and along the West Branch. By 1763, the Munsee had abandoned their island villages and other villages in the area.[11][12]

With the signing of the first Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, the British gained control from the Iroquois of lands south of the West Branch. However, white settlers continued to appropriate land, including tracts in and near the future site of Lock Haven, not covered by the treaty. In 1769, Cleary Campbell, the first white settler in the area, built a log cabin near the present site of Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania, and by 1773 William Reed, another settler, had built a cabin surrounded by a stockade and called it Reed's Fort.[13] It was the westernmost of 11 mostly primitive forts along the West Branch; Fort Augusta, located by the confluence of the East (or North) and West branches of the Susquehanna at what is now Sunbury, was the easternmost and most defensible. In response to settler incursions, and encouraged by the British during the American Revolution (1775–83), Indians attacked colonists and their settlements along the West Branch. Fort Reed and the other white settlements in the area were temporarily abandoned in 1778 during a general evacuation known as the Big Runaway. Hundreds of people fled along the river to Fort Augusta, about 50 miles (80 km) from Fort Reed; some did not return for five years.[14] In 1784, the second Treaty of Fort Stanwix, between the Iroquois and the United States, transferred most of the remaining Indian territory in Pennsylvania, including what would become Lock Haven, to the state.[15] The U.S. acquired the last remaining tract, the Erie Triangle, through a separate treaty and sold it to Pennsylvania in 1792.[15]

Nineteenth century

Lock Haven was laid out as a town in 1833,[16] and it became the county seat in 1839, when Clinton County was created out of parts of Lycoming and Centre counties.[17] Incorporated as a borough in 1840 and as a city in 1870,[16] Lock Haven prospered in the 19th century largely because of timber and transportation. The forests of Clinton County and counties upriver held a huge supply of white pine and hemlock as well as oak, ash, maple, poplar, cherry, beech, and magnolia. The wood was used locally for such things as frame houses, shingles, canal boats, and wooden bridges, and whole logs were floated to Chesapeake Bay and on to Baltimore, to make spars for ships. Log driving and log rafting, competing forms of transporting logs to sawmills, began along the West Branch around 1800. By 1830, slightly before the founding of the town, the lumber industry was well established.[18]

The West Branch Canal, which opened in 1834, ran 73 miles (117 km) from Northumberland to Farrandsville, about 5 miles (8 km) upstream from Lock Haven. A state-funded extension called the Bald Eagle Cut ran from the West Branch through Lock Haven and Flemington to Bald Eagle Creek. A privately funded extension, the Bald Eagle and Spring Creek Navigation, eventually reached Bellefonte, 24 miles (39 km) upstream. Lock Haven's founder, Jeremiah Church, and his brother, Willard, chose the town site in 1833 partly because of the river, the creek, and the canal. Church named the town Lock Haven because it had a canal lock and because it was a haven for loggers, boatmen, and other travelers. Over the next quarter century, canal boats 12 feet (4 m) wide and 80 feet (24 m) long carried passengers and mail as well as cargo such as coal, ashes for lye and soap, firewood, food, furniture, dry goods, and clothing. A rapid increase in Lock Haven's population (to 830 by 1850)[19] followed the opening of the canal.[20]

A Lock Haven log boom, smaller than but otherwise similar to the Susquehanna Boom at Williamsport, was constructed in 1849. Large cribs of timbers weighted with tons of stone were arranged in the pool behind the Dunnstown Dam, named for a settlement on the shore opposite Lock Haven. The piers, about 150 feet (46 m) from one another, stretched in a line from the dam to a point 3 miles (5 km) upriver. Connected by timbers shackled together with iron yokes and rings, the piers anchored an enclosure into which the river current forced floating logs. Workers called boom rats sorted the captured logs, branded like cattle, for delivery to sawmills and other owners. Lock Haven became the lumber center of Clinton County and the site of many businesses related to forest products.[21]

The Sunbury and Erie Railroad, renamed the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad in 1861, reached Lock Haven in 1859, and with it came a building boom. Hoping that the area's coal, iron ore, white pine, and high-quality clay would produce significant future wealth, railroad investors led by Christopher and John Fallon financed a line to Lock Haven. On the strength of the railroad's potential value to the city, local residents had invested heavily in housing, building large homes between 1854 and 1856. Although the Fallons' coal and iron ventures failed, Gothic Revival, Greek Revival, and Italianate mansions and commercial buildings such as the Fallon House, a large hotel, remained, and the railroad provided a new mode of transport for the ongoing timber era. A second rail line, the Bald Eagle Valley Railroad, originally organized as the Tyrone and Lock Haven Railroad and completed in the 1860s, linked Lock Haven to Tyrone, 56 miles (90 km) to the southwest. The two rail lines soon became part of the network controlled by the Pennsylvania Railroad.[22]

During the era of log floating, logjams sometimes occurred when logs struck an obstacle. Log rafts floating down the West Branch had to pass through chutes in canal dams. The rafts were commonly 28 feet (9 m) wide—narrow enough to pass through the chutes—and 150 feet (46 m) to 200 feet (61 m) long.[23] In 1874, a large raft got wedged in the chute of the Dunnstown Dam and caused a jam that blocked the channel from bank to bank with a pile of logs 16 feet (5 m) high. The jam eventually trapped another 200 log rafts, and 2 canal boats, The Mammoth of Newport and The Sarah Dunbar.[24]

In terms of board feet, the peak of the lumber era in Pennsylvania arrived in about 1885, when 1.9 million logs went through the boom at Williamsport. These logs produced a total of about 226 million board feet (533,000 m3) of sawed lumber. After that, production steadily declined throughout the state.[23] Lock Haven's timber business was also affected by flooding, which badly damaged the canals and destroyed the log boom in 1889.[25]

The Central State Normal School, established to train teachers for central Pennsylvania, held its first classes in 1877 at a site overlooking the West Branch Susquehanna River. The small school, with enrollments below 150 until the 1940s, eventually became Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania.[26] In the early 1880s, the New York and Pennsylvania Paper Mill in Castanea Township near Flemington began paper production on the site of a former sawmill; the paper mill remained a large employer until the end of the 20th century.

Twentieth century

As older forms of transportation such as the canal boat disappeared, new forms arose. One of these, the electric trolley, began operation in Lock Haven in 1894. The Lock Haven Electric Railway, managed by the Lock Haven Traction Company and after 1900 by the Susquehanna Traction Company, ran passenger trolleys between Lock Haven and Mill Hall, about 3 miles (5 km) to the west. The trolley line extended from the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad station in Lock Haven to a station of the Central Railroad of Pennsylvania, which served Mill Hall. The route went through Lock Haven's downtown, close to the Normal School, across town to the trolley car barn on the southwest edge of the city, through Flemington, over the Bald Eagle Canal and Bald Eagle Creek, and on to Mill Hall via what was then known as the Lock Haven, Bellefonte, and Nittany Valley Turnpike. Plans to extend the line from Mill Hall to Salona, 3 miles (5 km) south of Mill Hall, and to Avis 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Lock Haven, were never carried out, and the line remained unconnected to other trolley lines. The system, always financially marginal, declined after World War I. Losing business to automobiles and buses, it ceased operations around 1930.[27]

William T. Piper, Sr., built the Piper Aircraft Corporation factory in Lock Haven in 1937 after the company's Taylor Aircraft manufacturing plant in Bradford, Pennsylvania, was destroyed by fire. The factory began operations in a building that once housed a silk mill.[28] As the company grew, the original factory expanded to include engineering and office buildings. Piper remained in the city until 1984, when its new owner, Lear-Siegler, moved production to Vero Beach, Florida. The Clinton County Historical Society opened the Piper Aviation Museum at the site of the former factory in 1985, and 10 years later the museum became an independent organization.[28]

The state of Pennsylvania acquired Central State Normal School in 1915 and renamed it Lock Haven State Teachers College in 1927. Between 1942 and 1970, the student population grew from 146 to more than 2,300; the number of teaching faculty rose from 25 to 170, and the college carried out a large building program. The school's name was changed to Lock Haven State College in 1960, and its emphasis shifted to include the humanities, fine arts, mathematics, and social sciences, as well as teacher education. Becoming Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania in 1983, it opened a branch campus in Clearfield, 48 miles (77 km) west of Lock Haven, in 1989.[26]

An 8-acre (3.2 ha) industrial area in Castanea Township adjacent to Lock Haven was placed on the National Priorities List of uncontrolled hazardous waste sites (commonly referred to as Superfund sites) in 1982. Drake Chemical, which went bankrupt in 1981, made ingredients for pesticides and other compounds at the site from the 1960s to 1981. Starting in 1982, the United States Environmental Protection Agency began a clean-up of contaminated containers, buildings, and soils at the site and by the late 1990s had replaced the soils. Equipment to treat contaminated groundwater at the site was installed in 2000 and continues to operate.[29]

Floods

Pennsylvania's streams have frequently flooded. According to William H. Shank, the Native Americans of Pennsylvania warned white settlers that great floods occurred on the Delaware and Susquehanna rivers every 14 years. Shank tested this idea by tabulating the highest floods on record at key points throughout the state over a 200-year period and found that a major flood had occurred, on average, once every 25 years between 1784 and 1972. Big floods recorded at Harrisburg, on the main stem of the Susquehanna about 120 miles (193 km) downstream from Lock Haven, occurred in 1784, 1865, 1889, 1894, 1902, 1936, and 1972. Readings from the Williamsport stream gauge, 24 miles (39 km) below Lock Haven on the West Branch of the Susquehanna, showed major flooding between 1889 and 1972 in the same years as the Harrisburg station; in addition, a large flood occurred on the West Branch at Williamsport in 1946.[30] Estimated flood-crest readings between 1847 and 1979—based on data from the National Weather Service flood gauge at Lock Haven—show that flooding likely occurred in the city 19 times in 132 years.[31] The biggest flood occurred on March 18, 1936, when the river crested at 32.3 feet (9.8 m), which was about 11 feet (3.4 m) above the flood stage of 21 feet (6.4 m).[31]

The third biggest flood, cresting at 29.8 feet (9.1 m) in Lock Haven, occurred on June 1, 1889,[31] and coincided with the Johnstown Flood. The flood demolished Lock Haven's log boom, and millions of feet of stored timber were swept away.[32] The flood damaged the canals, which were subsequently abandoned, and destroyed the last of the canal boats based in the city.[25]

The most damaging Lock Haven flood was caused by the remnants of Hurricane Agnes in 1972. The storm, just below hurricane strength when it reached the region, made landfall on June 22 near New York City. Agnes merged with a non-tropical low on June 23, and the combined system affected the northeastern United States until June 25. The combination produced widespread rains of 6 to 12 inches (152 to 305 mm) with local amounts up to 19 inches (483 mm) in western Schuylkill County, about 75 miles (121 km) southeast of Lock Haven.[33] At Lock Haven, the river crested on June 23 at 31.3 feet (9.5 m), second only to the 1936 crest.[31] The flood greatly damaged the paper mill and Piper Aircraft.[34]

In 1992 federal, state, and local governments began construction of barriers to protect the city. The project included a levee of 36,000 feet (10,973 m) and a flood wall of 1,000 feet (305 m) along the Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek, closure structures, retention basins, a pumping station, and some relocation of roads and buildings. Completed in 1995, the levee protected the city from high water in the year of the Blizzard of 1996,[35] and again 2004, when rainfall from the remnants of Hurricane Ivan threatened the city.[34]

Geography

Lock Haven is the county seat of Clinton County.[36] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.7 square miles (7.0 km2), 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2) of which is land. About 0.2 square miles (0.5 km2), 6 percent, is water.[37]

Lock Haven is at 561 feet (171 m) above sea level near the confluence of Bald Eagle Creek and the West Branch Susquehanna River in north-central Pennsylvania.[2][38] The city is about 200 miles (320 km) by highway northwest of Philadelphia and 175 miles (280 km) northeast of Pittsburgh. U.S. Route 220, a major transportation corridor, skirts the city on its south edge, intersecting with Pennsylvania Route 120, which passes through the city and connects it with Renovo in northern Clinton County. Other highways entering Lock Haven include Pennsylvania Route 664 and Pennsylvania Route 150, which connects to Avis.[38]

The city and nearby smaller communities—Castanea, Dunnstown, Flemington, and Mill Hall—are mainly at valley level in the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, a mountain belt characterized by long even valleys running between long continuous ridges. Bald Eagle Mountain, one of these ridges, runs parallel to Bald Eagle Creek on the south side of the city.[28] Upstream of the confluence with Bald Eagle Creek, the West Branch Susquehanna River drains part of the Allegheny Plateau, a region of dissected highlands (also called the "Deep Valleys Section") generally north of the city.[39][40] The geologic formations in the southeastern part of the city are mostly limestone, while those to the north and west consist mostly of siltstone and shale. Large parts of the city are flat, but slopes rise to the west, and very steep slopes are found along the river, on the university campus, and along Pennsylvania Route 120 as it approaches U.S. Route 220.[28]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Lock Haven is in zone Dfa meaning a humid continental climate with hot or very warm summers.[41] The average temperature here in January is 28 °F (−2 °C), and in July it is 73 °F (23 °C). Between 1888 and 1996, the highest recorded temperature for the city was 106 °F (41 °C) in 1936, and the lowest recorded temperature was −22 °F (−30 °C) in 1912.[42] The average wettest month is June.[42] Between 1926 and 1977 the mean annual precipitation was about 39 inches (990 mm), and the number of days each year with precipitation of 0.1 inches (2.5 mm) or more was 77.[42] Annual snowfall amounts between 1888 and 1996 varied from 0 in several years to about 65 inches (170 cm) in 1942. The maximum recorded snowfall in a single month was 38 inches (97 cm) in April 1894.[42]

| Climate data for Lock Haven, Pennsylvania | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

75 (24) |

86 (30) |

97 (36) |

102 (39) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

93 (34) |

84 (29) |

70 (21) |

106 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 36 (2) |

38 (3) |

49 (9) |

63 (17) |

75 (24) |

82 (28) |

86 (30) |

84 (29) |

77 (25) |

65 (18) |

51 (11) |

39 (4) |

62 (17) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

37 (3) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

59 (15) |

58 (14) |

51 (11) |

40 (4) |

32 (0) |

23 (−5) |

39 (4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−21 (−29) |

−12 (−24) |

5 (−15) |

25 (−4) |

34 (1) |

31 (−1) |

32 (0) |

20 (−7) |

18 (−8) |

5 (−15) |

−15 (−26) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.4 (61) |

2.2 (56) |

3.4 (86) |

3.4 (86) |

3.9 (99) |

4.3 (110) |

3.7 (94) |

3.3 (84) |

3.0 (76) |

3.1 (79) |

3.1 (79) |

2.7 (69) |

38.5 (979) |

| Source: Pennsylvania State Climatologist[42] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 830 | — | |

| 1860 | 3,349 | 303.5% | |

| 1870 | 6,986 | 108.6% | |

| 1880 | 5,845 | −16.3% | |

| 1890 | 7,358 | 25.9% | |

| 1900 | 7,210 | −2.0% | |

| 1910 | 7,772 | 7.8% | |

| 1920 | 8,557 | 10.1% | |

| 1930 | 9,668 | 13.0% | |

| 1940 | 10,810 | 11.8% | |

| 1950 | 11,381 | 5.3% | |

| 1960 | 11,748 | 3.2% | |

| 1970 | 11,427 | −2.7% | |

| 1980 | 9,617 | −15.8% | |

| 1990 | 9,230 | −4.0% | |

| 2000 | 9,149 | −0.9% | |

| 2010 | 9,772 | 6.8% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 9,083 | [5] | −7.1% |

| Sources:[4][43] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 9,772 people living in 3,624 housing units spread across the city. The average household size during the years 2009–13 was 2.38. During those same years, multi-unit structures made up 57 percent of the housing-unit total. The rate of home ownership was 35 percent, and the median value of owner-occupied units was about $100,000. The estimated population of the city in 2013 was 10,025, an increase of 2.6 percent after 2010.[4]

The population density in 2010 was 3,915 people per square mile (1,506 per km2). The reported racial makeup of the city was about 93 percent White and about 4 percent African-American, with other categories totaling about 3 percent. People of Hispanic or Latino origin accounted for about 2 percent of the residents. Between 2009 and 2013, about 2 percent of the city's residents were foreign-born, and about 5 percent of the population over the age of 5 spoke a language other than English at home.[4]

In 2010, the city's population included about 16 percent under the age of 18 and about 12 percent who were 65 years of age or older.[4] Females accounted for 54 percent of the total.[4] Students at the university comprised about a third of the city's population.[28]

Between 2009 and 2013, of the people who were older than 25, 82 percent had graduated from high school, and 20 percent had at least a bachelor's degree. In 2007, 640 businesses operated in Lock Haven. The mean travel time to work for employees who were at least 16 years old was 16 minutes.[4]

The median income for a household in the city during 2009–13 was about $25,000 compared to about $53,000 for the entire state of Pennsylvania. The per capita income for the city was about $19,000, and about 40 percent of Lock Haven's residents lived below the poverty line.[4]

Economy

Lock Haven's economy, from the city's founding in 1833 until the end of the 19th century, depended heavily on natural resources, particularly timber, and on cheap transportation to eastern markets.[28] Loggers used the Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek to float timber to sawmills in Lock Haven and nearby towns. The West Branch Canal, reaching the city in 1834, connected to large markets downstream, and shorter canals along Bald Eagle Creek added other connections.[20] In 1859, the first railroad arrived in Lock Haven, spurring trade and economic growth.[28]

By 1900, the lumber industry had declined, and the city's economic base rested on other industries, including a furniture factory, a paper mill, a fire brick plant, and a silk mill. In 1938, the Piper Aircraft Corporation, maker of the Piper Cub and other light aircraft, moved its production plant to Lock Haven. It remained one of the city's biggest employers until the 1980s, when, after major flood damage and losses related to Hurricane Agnes in 1972, it moved to Florida.[28] The loss of Piper Aircraft contributed to an unemployment rate of more than 20% in Lock Haven in the early 1980s, though the rate had declined to about 9% by 2000. Another large plant, the paper mill that had operated since the 1880s[44] in Castanea Township, closed in 2001.[45] By 2005, 32% of the city's labor force was employed in health care, education, or social services, 16% in manufacturing, 14% in retail trade, 13% in arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services, and smaller fractions in other sectors. The city's biggest employers, Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania and UPMC Susquehanna Lock Haven hospital, are among the seven biggest employers in Clinton County.[28]

Arts, culture, historic sites, and media

Lock Haven University presents public concerts, plays, art exhibits, and student recitals at the Price Performance Center, the Sloan Auditorium, and the Sloan Fine Arts Gallery on campus.[46] The Millbrook Playhouse in Mill Hall has produced plays since 1963.[47] Summer concerts are held in city parks,[48] and the local Junior Chamber International (Jaycees) chapter sponsors an annual boat regatta on the river.[49] The city sponsors a festival called Airfest at the airport in the summer, a Halloween parade in October, and a holiday parade in December. Light-airplane pilots travel to the city in vintage Piper planes to attend Sentimental Journey Fly-Ins, which have been held each summer since 1986.[50] Enthusiasts of radio-controlled model airplanes meet annually at the William T. Piper Memorial Airport to fly their planes.[51]

The central library for Clinton County is the Annie Halenbake Ross Library in Lock Haven; it has about 130,000 books, subscriptions to periodicals, electronic resources, and other materials.[52] Stevenson Library on the university campus has additional collections.[53]

The Piper Aviation Museum exhibits aircraft and aircraft equipment, documents, photographs, and memorabilia related to Piper Aircraft. An eight-room home, the Heisey House, restored to its mid-19th-century appearance, displays Victorian-era collections; it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and is home to the Clinton County Historical Society.[54] The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission has placed three cast aluminum markers—Clinton County, Fort Reed, and Pennsylvania Canal (West Branch Division)—in Lock Haven to commemorate historic places.[55] The Water Street District, a mix of 19th- and 20th-century architecture near the river, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[56] Memorial Park Site 36Cn164, an archaeological site of prehistoric significance discovered near the airport, was added to the National Register in 1982.[57]

The city's media include The Express, a daily newspaper, and The Eagle Eye, the student newspaper at the university.[58] Radio stations WBPZ (AM) and WSQV (FM) broadcast from the city. A television station, Havenscope (available on-campus only), and a radio station, WLHU (Internet station only, with no FCC broadcast license), both managed by students, operate on the university campus.[58]

Parks and recreation

The city has 14 municipal parks and playgrounds ranging in size from the 0.75-acre (0.30 ha) Triangle Park in downtown to the 80-acre (32 ha) Douglas H. Peddie Memorial Park along Route 120. Fields maintained by the city accommodate baseball for the Pony League, Little League, and Junior League and softball for the Youth Girls League and for adults. In 1948, a team from the city won the Little League World Series.[59] In 2011, the Keystone Little League based in Lock Haven advanced to the Little League World Series and placed third in the United States, drawing record crowds.[60] Hanna Park includes tennis courts, and Hoberman Park includes a skate park. The Lock Haven City Beach, on the Susquehanna River, offers water access, a sand beach, and a bath house. In conjunction with the school district, the city sponsors a summer recreation program.[28]

A 25-mile (40 km) trail hike and run, the Bald Eagle Mountain Megatransect,[61] took place annually near Lock Haven until it was replaced in 2016 by a similar event, the 27-mile (43 km) Boulder Beast.[62] The local branch of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) offers a wide variety of recreational programs to members, and the Clinton Country Club maintains a private 18-hole golf course in Mill Hall.[63]

Government

Lock Haven has a council–manager form of government. The council, the city's legislative body, consists of six members and a mayor, each serving a four-year term. The council sets policy, and the city manager oversees day-to-day operations. The mayor is Joel Long, whose term expires in 2024.[64] The manager is Gregory J. Wilson.[65]

Lock Haven is the county seat of Clinton County and houses county offices, courts, and the county library. Three elected commissioners serving four-year terms manage the county government. Miles Kessinger, Jeffrey Snyder, and Angela Harding have terms running from 2020 through 2023.[66]

Stephanie Borowicz, a Republican, represents the 76th District, which includes Lock Haven, in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.[67] Cris Dush, a Republican, represents Lock Haven as part of the 25th District of the Pennsylvania State Senate.[67]

Education

The Keystone Central School District serves most of Clinton County, including Lock Haven, as well as parts of Centre County and Potter County. Three of the district's elementary schools are in Lock Haven: Dickey Elementary, Robb Elementary, and Woodward Elementary. All of these schools are for children enrolled in kindergarten through fifth grade. The total enrollment of these three schools combined in 2002–03 was 790.[28] There is a fourth elementary school in Mill Hall simply called Mill Hall Elementary located directly behind the Middle School. Central Mountain Middle School in Mill Hall is the nearest public middle school, for grades six to eight. The nearest public high school, grades nine to twelve, is Central Mountain High School, also in Mill Hall.[28] The District Administration Offices are housed at the Central Mountain High School location.

The city has two private schools, Lock Haven Christian School, with about 80 students in kindergarten through 12th grade, and Lock Haven Catholic School, which had about 190 students in kindergarten through sixth grade as of 2002–03.[28] In 2015, the Catholic School is completing a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) expansion to include grades seven and eight, which will make it a combined elementary and middle school.[68]

Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania, offering a wide range of undergraduate studies as well as continuing-education and graduate-school programs at its main campus, occupies 175 acres (71 ha) on the west edge of the city. Enrollment at this campus was about 4,400 in 2003.[28]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Lock Haven Taxi, based in the central downtown, has taxicabs for hire. Fullington Trailways provides daily intercity bus service between Lock Haven and nearby cities including State College, Williamsport, and Wilkes-Barre. Charter and tour buses are available through Susquehanna Trailways, based in Avis, 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Lock Haven. Pennsylvania Bicycle Route G follows Pennsylvania Route 150 and links to the Pine Creek Rail Trail at the eastern end of the county near Jersey Shore, Pennsylvania. A 2.5-mile (4.0 km) walking trail on the levee along the river is restricted to pedestrian use.[28]

The Norfolk Southern Railway's Buffalo Line mainline from Harrisburg to Buffalo, New York, runs through the center of Lock Haven. On the east side of town, it connects to the Nittany and Bald Eagle Railroad, a short line. Trains serving Lock Haven carry only freight. The City of Lock Haven operates the William T. Piper Memorial Airport, a general aviation facility with a paved runway, runway lighting, paved taxiways, a tie-down area, and hangar spaces. No commercial, charter, or freight services are available at this airport.[28]

Utilities

Electric service to Lock Haven residents is provided by PPL Electric Utilities (formerly known as Pennsylvania Power and Light).[69][70] UGI Central Penn Gas provides natural gas to the city.[71][72] Verizon Communications handles local telephone service; long-distance service is available from several providers. Comcast offers high-speed cable modem connections to the Internet. Several companies can provide Lock Haven residents with dial-up Internet access. One of them, KCnet, has an office in Lock Haven. Comcast also provides cable television.[28]

The City of Lock Haven owns the reservoirs and water distribution system for Wayne Township, Castanea Township, and the city. Water is treated at the Central Clinton County Water Filtration Authority Plant in Wayne Township before distribution. The city also provides water to the Suburban Lock Haven Water Authority, which distributes it to surrounding communities. Lock Haven operates a sewage treatment plant for waste water, industrial waste, and trucked sewage from the city and eight upstream municipalities: Bald Eagle Township, Castanea, Flemington, Lamar, Mill Hall, Porter Township, Woodward Township, and Walker Township in Centre County. Storm water runoff from within the city is transported by city-owned storm sewers. Curbside pickup of household garbage is provided by a variety of local haulers licensed by the city; recyclables are picked up once every two weeks. The Clinton County Solid Waste Authority owns and operates the Wayne Township Landfill, which serves Lock Haven.[28]

Health care

UPMC Susquehanna Lock Haven hospital is a 47-bed hospital with a 90-bed skilled-nursing wing that includes a 34-bed dementia unit.[73] It offers inpatient, outpatient, and 24-hour emergency services with heliport access. Susque-View Home, next to the hospital, offers long-term care to the elderly and other services including speech, physical, and occupational therapy for people of all ages. A 10-physician community-practice clinic based in the city provides primary care and specialty services. A behavioral health clinic offers programs for children and adolescents and psychiatric outpatient care for all ages.[28]

Notable people

Brittani Kline, winner of America's Next Top Model (cycle 16), is a 2015 graduate of Lock Haven University.[74] Alexander McDonald, a U.S. Senator from Arkansas, was born near Lock Haven in 1832.[75] Artist John French Sloan was born in Lock Haven in 1871,[76] and cartoonist Alison Bechdel, author of Dykes to Watch Out For and Fun Home, was born in Lock Haven in 1960.[77] Richard Lipez, author of the Donald Strachey mysteries, was born in Lock Haven in 1938.[78] Other notable residents have included diplomat and Dartmouth College president John Sloan Dickey,[79] federal judge Kermit Lipez of the U.S. Federal First District Court of Appeals,[80] and C. J. Snare, singer and songwriter for the band FireHouse.[81]

References

- Wagner 1979, p. 6.

- "City of Lock Haven". Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). United States Geological Survey. August 30, 1990. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "State and County QuickFacts: Lock Haven (city), Pennsylvania". U.S. Census Bureau. March 31, 2015. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. "Pennsylvania Archaeology: An Introduction". Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- Schuldenrein & Vento 1994, p. 1, chapter 1.

- Richter 2002, p. 4.

- At the time of first contact, several tribes lived in what later became Pennsylvania. It is not known which tribe made first contact with Europeans.

- Wallace 1987, p. frontispiece (map).

- Miller 1966, p. 4.

- The earliest recorded inhabitants of the West Branch Susquehanna River valley were the Susquehannocks, but they were wiped out by disease and warfare with the Iroquois, and the few members left moved west or were assimilated into other tribes by 1675. After that the Iroquois, who were the nominal rulers of the land but mostly lived in New York to the north, invited tribes displaced by European settlers to move into the region. These included the Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, and others. Generally, they moved west into the Ohio River Valley. For more information see Wallace, Paul A.W. (2005). Indians in Pennsylvania (Second ed., revised by William A. Hunter). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.OCLC 1744740 (Note: OCLC refers to the 1961 First Edition). Retrieved on December 21, 2009.

- Miller 1966, pp. 18, 23.

- Miller 1966, p. 28.

- Day, Sherman (1843). Historical collections of the State of Pennsylvania (Google Books online reprint). Philadelphia: George W. Gorton. pp. 315–16. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Clinton County – 7th class" (PDF). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- Linn 1883, p. 489.

- Miller 1966, pp. 109–111.

- Wagner 1979, p. 42.

- Miller 1966, pp. 44–46.

- Miller 1966, pp. 111–119.

- Wagner 1979, pp. 9–60.

- Theiss, Lewis Edwin (October 1952). "Lumbering in Penn's Woods" (PDF). Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical Association. 19 (4): 397–412. psu.ph/1133209642. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- Miller 1966, pp. 119–120.

- Miller 1966, p. 59.

- "Lock Haven University: A Brief History". Lock Haven University. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- Shieck & Cox 1978, pp. 81–92.

- City of Lock Haven Planning Office; Clinton County Comprehensive Planning Advisory Committee; Gannett Fleming, Inc.; Larson Design Group. "Comprehensive Plan Update (2005)" (PDF). City of Lock Haven. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2007.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Mid-Atlantic Superfund: Drake Chemical: Current Site Information". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- Shank 1972, pp. 10–13.

- Schuldenrein & Vento 1994, pp. 4–5, chapter 2, table 1.

- Shank 1972, pp. 22–23.

- "Hurricane Agnes – June 14–25, 1972". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Yowell, Robert (March 2005). "Intergovernmental Success in Multi-Component Flood Mitigation: The Lock Haven Flood Protection Project Experience" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary Water Research and Education (129): 46–48. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- "Statewide Floods in Pennsylvania, January 1996". United States Geological Survey. April 10, 1996. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. 2005. Archived from the original on June 26, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- "United States Gazetteer files: 2014 (places)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- The Road Atlas (Map) (2008 ed.). Rand McNally & Company. § 86–89. ISBN 0-528-93961-0.

- "Landforms of Pennsylvania from Map 13, Physiographic Provinces of Pennsylvania" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Memorial Park Site, 36Cn164" (PDF). United States National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- Kottek, Marcus; Greiser, Jürgen; et al. (June 2006). "World Map of Köppen–Geiger Climate Classification". Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 261. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- Pennsylvania State Climatologist. "Lock Haven Local Climatological Data". College of Earth and Mineral Sciences at The Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- Wagner 1979, p. 134.

- "Plan to Close Paper Mill Staggers Lock Haven". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. October 18, 2000. Retrieved September 10, 2019 – via Google News.

- "Cultural Events, Spring 2015" (PDF). Lock Haven University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- Davis, Lindsay (July 5, 2008). "Millbrook Playhouse in Review: 'Rebound & Gagged' Will Have You Choking with Laughter". The Express. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- "Summer Concert Series". City of Lock Haven. 2015. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- "Over 300 Boats Expected". The Express. August 26, 2008. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- Editorial staff (June 17, 2008). "Welcome All to 23rd Annual Piper Fly-in". The Express. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- "Wings of Williamsport R/C Flying Club". Wings of Williamsport, Incorporated. 2009. Archived from the original on June 4, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- "Annie Halenbake Ross Library – Lock Haven, Pennsylvania – Central Library". Education Bug. Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- "Lock Haven University Libraries". Lock Haven University. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Heisey House" (PDF). National Park Service. August 1, 1971. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- "Historical Marker Program". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Water Street District" (PDF). National Park Service. May 16, 1973. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Memorial Park Site 36Cn164" (PDF). National Park Service. September 1, 1980. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- "Student Media". Lock Haven University. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- "Little League Baseball World Series Champions". Little League Baseball Incorporated. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- Rothdeutsch, Pat (August 22, 2013). "That Magical Season: Remembering the Keystone Little League's Amazing Run". Central Daily Times. State College, Pa. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- Mazza, Rachel (October 5, 2009). "Trail Love Blossoms as Couple Ties the Knot at Megatransect". The Express.

- "Boulder Beast Announced for Sept. 2016". The Record. The Record Online. September 29, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "Welcome to Clinton Country Club". Clinton Country Club. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- "Elected Officials". City of Lock Haven. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "City Manager". City of Lock Haven. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- "Commissioners". Clinton County Government. 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "Pennsylvania General Assembly: Find Your Legislator". Pennsylvania State Legislature. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "Lock Haven Catholic School Groundbreaking". The Record. The Record Online. October 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- "Service Area". PPL Electric Utilities. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- "General Tariff" (PDF). PPL Electric Utilities. June 20, 2017. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- "Geographic Footprint". UGI. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "Gas Tariff" (PDF). UGI Central Penn Gas. July 7, 2017. pp. 5–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "UPMC Susquehanna Lock Haven". UPMC Susquehanna. 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- Hewitt, Lyndsey (October 13, 2013). "Fashion and Life – a Balancing Act: Brittani Kline's Journey in the Modeling Industry". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- "McDonald, Alexander, (1832–1903)". United States Congress. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- Cleck, Amanda. "Sloan, John French". The Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- "Biography for Alison Bechdel". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- Connor, Matt (August 16, 2008). "Author Brings Old LH Family Name to National Prominence". The Express. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- Flint, Peter B. (February 11, 1991). "John Sloan Dickey Is Dead at 83; Dartmouth President for 25 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- "Muskie Oral Histories: Interview with Kermit Lipez by Andrea L'Hommedieu" (PDF). Bates College. September 20, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "Old Photo Album". The Express. November 4, 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

Sources

- Linn, John Blair (1883). History of Centre and Clinton Counties, Pennsylvania (Digitized scan from the Pennsylvania State University digital library collections) (1st ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Louis H. Everts. Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- Miller, Isabel Winner (1966). Old Town: A History of Early Lock Haven, 1769–1845. Lock Haven: The Annie Halenbake Ross Library. OCLC 7151032.

- Richter, Daniel K. (2002). "Chapter 1. The First Pennsylvanians". In Miller, Randall M.; Pencak, William A. (eds.). Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth. The Pennsylvania State University and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. pp. 3–46. ISBN 978-0-271-02213-0.

- Schuldenrein, Joseph; Vento, Frank (July 19, 1994). "Geoarcheological Investigations at the Memorial Park Site (36CN164), Pennsylvania" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- Shank, William H. (1972). Great Floods of Pennsylvania: A Two-Century History (2nd ed.). York, Pennsylvania: American Canal and Transportation Center. ISBN 978-0-933788-38-1.

- Shieck, Paul J.; Cox, Harold E. (1978). West Branch Trolleys: Street Railways of Lycoming & Clinton Counties. Forty Fort, Pennsylvania: Harold E. Cox. OCLC 6163575.

- Wagner, Dean R., ed (1979). Historic Lock Haven: An Architectural Survey. Lock Haven: Clinton County Historical Society. OCLC 5216208.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Wallace, Paul A.W. (1987). Indian Paths of Pennsylvania (4th printing ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 978-0-89271-090-4..

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. |

- Official website

- The Express, local newspaper