Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic

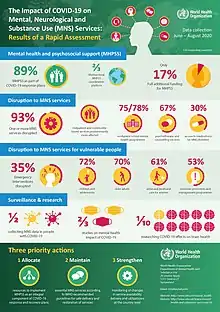

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of people around the world.[1] Similar to the past respiratory viral epidemics, such as the SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and the influenza epidemics, COVID-19 pandemic had caused anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in different population groups, including the healthcare workers, general public, and the patients and quarantined individuals.[2] The Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee of the United Nations recommends that the core principles of mental health support during an emergency are "do no harm, promote human rights and equality, use participatory approaches, build on existing resources and capacities, adopt multi-layered interventions and work with integrated support systems."[3] COVID-19 is affecting people's social connectedness, their trust in people and institutions, their jobs and incomes, as well as imposing a huge toll in terms of anxiety and worry.[4]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

COVID-19 also adds to the complexity of substance use disorders (SUDs) as it disproportionately affects people with SUD due to accumulated social, economic, and health inequities.[5] The health consequences of SUDs (for example, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, type 2 diabetes, immunosuppression and central nervous system depression, and psychiatric disorders) and the associated environmental challenges (e.g., housing instability, unemployment, and criminal justice involvement) increase risk for COVID-19. COVID-19 public health mitigation measures (i.e., physical distancing, quarantine and isolation) can exacerbate loneliness, mental health symptoms, withdrawal symptoms and psychological trauma. Confinement rules, unemployment and fiscal austerity measures during and following the pandemic period can affect the illicit drug market and drug use patterns.

Causes of mental health issues during COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused stress, anxiety and worry for many individuals, arising both from the disease itself and from response measures such as social distancing. Common causes of psychological stress during pandemics include, fear of falling ill and dying, avoiding health care due to fear of being infected while in care, fear of losing work and livelihoods, fear of being socially excluded, fear of being placed in quarantine, feeling of powerlessness in protecting oneself and loved ones, fear of being separated from loved ones and caregivers, refusal to care for vulnerable individuals due to fear of infection, feelings of helplessness, lack of self-esteem to do anything in daily life, boredom, loneliness, and depression due to being isolated, and fear of re-living the experience of a previous pandemic.[3][6]

In addition to these problems, COVID-19 can cause additional psychological responses, such as, risk of being infected when the transmission mode of COVID-19 is not 100% clear, common symptoms of other health problems being mistaken for COVID-19, increased worry about children being at home alone (during school shutdowns, etc.) while parents have to be at work, and risk of deterioration of physical and mental health of vulnerable individuals if care support is not in place.[3]

Frontline workers, such as doctors and nurses may experience additional mental health problems. Stigmatization towards working with COVID-19 patients, stress from using strict biosecurity measures (such as physical strain of protective equipment, need for constant awareness and vigilance, strict procedures to follow, preventing autonomy, physical isolation making it difficult to provide comfort to the sick), higher demands in the work setting, reduced capacity to use social support due to physical distancing and social stigma, insufficient capacity to give self-care, insufficient knowledge about the long-term exposure to individuals infected with COVID-19, and fear that they could pass infection to their loved ones can put frontline workers in additional stress.[3][7][8]

Prevention and management of mental health conditions

_v1.jpg.webp)

World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control guidelines

The World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control have issued guidelines for preventing mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. The summarized guidelines are as follows:[9][10]

For general population

- Be empathetic to all the affected individuals, regardless of their nationality or ethnicity.

- Use people-first language while describing individuals affected with COVID-19.

- Minimize watching the news if that makes one anxious. Seek information only from trusted sources, preferably once or twice a day.

- Protect yourself and be supportive to others, such as your neighbours.

- Find opportunities to amplify positive stories of local people who have experienced COVID-19.

- Honor healthcare workers who are supporting those affected with COVID-19.

For healthcare workers

- Feeling under pressure is normal during the times of a crisis. Managing one's mental health is as important as managing physical health.

- Follow coping strategies, ensure sufficient rest, eat good food, engage in physical activity, avoid using tobacco, alcohol, or drugs. Use the coping strategies that have previously worked for you under stressful situations.

- If one is experiencing avoidance by the family or the community, stay connected with loved ones, including digital methods.

- Use understandable ways to share messages to people with disabilities.

- Know how to link people affected with COVID-19 with available resources.

For team leaders in health facilities

- Keep all staff protected from poor mental health. Focus on long-term occupational capacity rather than short term results.

- Ensure good quality communication and accurate updates.

- Ensure that all staff are aware of where and how mental health support can accessed.

- Orient all staff on how to provide psychological first aid to the affected.

- Emergency mental health conditions should be managed in healthcare facilities.

- Ensure availability of essential psychiatric medications at all levels of health care.

For carers of children

- Help children find positive ways to express their emotions.

- Avoid separating children from their parents/carers as much as possible. Ensure that regular contact with parents and carers is maintained, should the child be placed in isolation.

- Maintain family routines as much as possible and provide age-appropriate engaging activities for children.

- Children might seek more attachment from parents, in which case, discuss about COVID-19 with them in an age-appropriate way.

- Explain in a way that the child can understand what is happening, and why we as a society are taking the preventive measures.

For older adults, people with underlying health conditions, and their carers

- Older adults, those especially in isolation or suffering from pre-existing neurological conditions, may become more anxious, angry, or withdrawn. Provide practical and emotional support through caregivers and healthcare professionals.

- Share simple facts on the crisis and give clear information about how to reduce the risk of infection.

- Have access to all the medications that are currently being used.

- Know in advance where and how to get practical help.

- Learn and perform simple daily exercises to practice at home.

- Keep regular schedules as much as possible and keep in touch with loved ones.

- Indulge in a hobby or task that helps focus the mind on other aspects.

- Reach out to people digitally or telephonically to have normal conversations or do a fun activity together online.

- Try and do good for the community with social distancing measures in place. It could be providing meals to the needy, dry rations, or coordination.

For people in isolation

- Stay connected and maintain social networks.

- Pay attention to your own needs and feelings. Engage in activities that you find relaxing.

- Avoid listening to rumors that make you uncomfortable.

- Begin new activities if you can.

- Find new ways to exactly stay connected, use Jitsi or other instant messaging clients to have multiple chats with friends and family.

- Be sure to keep routine.

China

A detailed psychological intervention plan was developed by the Second Xiangya Hospital, the Institute of Mental Health, the Medical Psychology Research Center of the Second Xiangya Hospital, and the Chinese Medical and Psychological Disease Clinical Medicine Research Center. It focused on building a psychological intervention medical team to provide online courses for medical staff, a psychological assistance hotline team, and psychological interventions.[11] Online mental health education and counselling services were created for social media platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and TikTok that were widely used by medical staff and the public. Printed books about mental health and COVID-19 were republished online with free electronic copies available through the Chinese Association for Mental Health.[12]

United States

Due to the increase in telecommunication for medical and mental health appointments, the United States government loosened the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) through a limited waiver. This allows clinicians to evaluate and treat individuals though video chatting services that were not previously compliant, allowing for patients to socially distance and receive care.[13] On October 5, 2020, President Donald Trump issued an executive order to address the mental and behavioral health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and its mitigation, including the establishment of a Coronavirus Mental Health Working Group. In the executive order, he cited a report from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which found that during June 24–30, 2020, 40.9% of more than 5,000 Americans reported at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition, and 10.7% had seriously considering suicide during the month preceding the survey.[14] On 9 November 2020, a peer-reviewed paper published in Lancet Psychiatry reported findings from an electronic health record network cohort study using data from nearly 70 million individuals, including 62,354 who had a diagnosis of COVID-19.[15] Nearly 20% of COVID-19 survivors were diagnosed with a psychiatric condition between 14–90 days after diagnosis with COVID-19, including 5.8% first-time psychiatric diagnoses. Among all patients without previous psychiatric history, patients hospitalized for COVID-19 also had increased incidence of a first psychiatric diagnosis compared to other health events analyzed. Together, these findings suggest that those with COVID-19 may be more susceptible to psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19, and those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions may be at increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19.

Impact on individuals with anxiety disorders

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

There has been a heightened concern for individuals suffering from obsessive–compulsive disorder, especially in regards to long-term consequences.[16][17] Fears regarding infection by the virus, and public health tips calling for hand-washing and sterilization are triggering related compulsions in some OCD sufferers.[18] Some OCD sufferers with cleanliness obsessions are noticing their greatest fears realized.[19][20] Amid guidelines of social-distancing, quarantine, and feelings of separation, some sufferers are seeing an increase in intrusive thoughts, unrelated to contamination obsessions.[21][22]

Post-traumatic stress disorder

There has been a particular concern for sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as the potential for medical workers and COVID–19 patients to develop PTSD-like symptoms.[23][24][25] In late March 2020, researchers in China found that, based on a PTSD checklist questionnaire provided to 714 discharged COVID–19 patients, 96.2% had serious prevalent PTSD symptoms.[26]

Impact on children

Academics have reported that for many children who were separated from caregivers during the pandemic, it may place them into a state of crisis, and those who were isolated or quarantined during past pandemic disease are more likely to develop acute stress disorders, adjustment disorders and grief, with 30% of children meeting the clinical criteria for PTSD.[27]

School closures also caused anxiety for students with special needs as daily routines are suspended or changed and all therapy or social skills groups also halted. Others who have incorporated their school routines into coping mechanisms for their mental health, have had an increase in depression and difficulty in adjusting back into normal routines. Additional concern has been shown towards children being placed in social isolation due to the pandemic, as rates of child abuse, neglect, and exploitation increased after the Ebola outbreak.[28] The closures have also limited the amount of mental health services that some children have access to, and some children are only identified as having a condition due to the training and contact by school authorities and educators.[13] A recent article published from India has observed a very high value of psychological distress in children due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, most (around 68%) of quarantined children showed some form of psychological distress which is much higher than the non-quarantined group, especially worry, fear, and helplessness.[29] In recent global study (Aristovnik et al., 2020), the negative emotions experienced by the students were boredom (45.2%), anxiety (39.8%), frustration (39.1%), anger (25.9%), hopelessness (18.8%), and shame (10.0%). The highest levels of anxiety were found in South America (65.7%) and Oceania (64.4%), followed by North America (55.8%) and Europe (48.7%). Least anxious were students from Africa (38.1%) and Asia (32.7%). A similar order of continents was found for frustration as the second-most devastating emotion.[30]

Impact on students

The COVID-19 pandemic has had considerable impact on students through direct effects of the pandemic, but also through the implementation of stay-at-home orders.[6] Academic stress, dissatisfaction with the quality of teaching and fear of being infected were associated with higher scores of depression in students.[6] Higher scores of depression were also associated with higher levels of frustration and boredom, inadequate supplies of resources, inadequate information from public health authorities, insufficient financial resources and perceived stigma.[6] Being in a steady relationship and living together with others were associated with lower depressive scores.[6]

Impact on essential workers and medical personnel

Many medical staff in China refused psychological interventions even though they showed sign of distress by; excitability, irritability, unwillingness to rest and others, stating they did not need a psychologist but more rest without interruption and enough protective supplies. They also stated using the psychologists skills instead towards the patients anxiety, panic, and other emotional problems instead of having the medical staff treat these issues.[11]

Many healthcare organizations provided resources for staff who were feeling the mental strain of caring. Some set up "wobble rooms", which are separate rooms for staff who need a safe place to "have a wobble", or to cope with their emotional states.[31]

Impact on suicides

The coronavirus pandemic has been followed by a concern for a potential spike in suicides, exacerbated by social isolation due to quarantine and social-distancing guidelines, fear, and unemployment and financial factors.[32][33] As of November 2020, researchers found that suicide rates were either the same or lower than before the pandemic began, especially in higher income countries.[34] It is not unusual for a crisis to temporarily reduce suicide rates.[34]

The number of phone calls to crisis hotlines has increased, and some countries have established new hotlines. For example, Ireland launched a new hotline aimed at older people in March 2020.[35]

China

One Shanghai distract reported that there have been 14 cases of suicides by primary and secondary school students so far this year, the number of which was more than annual numbers added for the last three years.[36] However, since the central government concern the heightened post-lockdown anxiety as domestic media report a spate of suicides by young people and topic like suicide is usually a taboo in Chinese society,[36] Information about suicide cases in China is limited.

India

There are reports of people committing suicide after not being able to access alcohol during the lockdown in India.[37]

Japan

Jun Shigemura and Mie Kurosawa suggested that people has been influenced not only by anxiety- and trauma-related disorders but also by adverse societal dynamics which related to work and the serious shortages of personal protective equipment.[38]

Overall, suicide rates in Japan appeared to decrease 20% during the earlier months of the pandemic, but that reduction was partly offset by a rise in August 2020.[34]

Several counseling helplines by telephone or text message are provided by many organizations, including the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.[39]

On September 20, 2020, the Sankei Shimbun reported that the month of July and August saw more people committing suicide than in the previous year due to the ongoing economical impact of the pandemic. Estimates for suicide deaths include a 7.7% increase or a 15.1% increase in August 2020, compared to August 2019.[34] The Sankei also reported that more women were committing suicide at a higher year than the previous year, with the month of August seeing a 40.1% increase in suicide compared to August 2019.[40]

United States

As of November 2020, the rate of deaths from suicide appears to be the same in the US as before the pandemic.[34] In Clark County, Nevada, 18 high school students committed suicide over nine months of school closures.[41]

In March 2020, the federal crisis hotline, Disaster Distress Helpline, received a 338% increase in calls compared to the previous month (February 2020) and an 891% increase in calls compared to the previous year (March 2019).[42]

In May 2020, the public health group Well Being Trust estimated that, over the coming decade of the 2020s, the pandemic and the related recession might indirectly cause an additional 75,000 deaths of despair (including overdose and suicide) than would otherwise be expected in the United States.[43][44]

Lockdown and mental health

The first lockdown was adopted in China and then in some other involved countries.[45] The policy included mandatory use of masks, gloves, and protective eyewear; implementing of social distancing, travel restrictions, closing of majority of workplaces, school, and public places.[46] There is potential risk in the measurement of mental health by lockdown since people may feel fear, despair, and uncertainty during the lockdown.[47] Furthermore, because most of mental health centers was closed during the lockdown, patients who already with mental problems may get worsen.[46] There are five major stressors during the lockdown: duration of lockdown, fear of infections, feelings of frustration and boredom, worries of inadequate supplies, and lack of information.[6]

Japan

In July 2020, Japan was still in "mild lockdown", which was not enforceable and non-punitive, with the declaration of a state of emergency.[48] According to a research of 11,333 individuals living across Japan which assigned for evaluate the impact after one-month "mild lockdown" through a questionnaire which asked questions related lifestyle, stress management, and stressors during the lockdown, it suggested that psychological distress indices significantly correlated with several items relating to COVID-19.[49]

Italy

Italy was the first country that entered a nationwide lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. According to the questionnaire, the prevalence of participants who report moderate to extremely high levels of depression was 21.2% of the population, while moderate to extremely high levels of anxiety was reported in 18.7%.[50] Moreover, about 40.5% of participants in the same research reported that they were experiencing poor sleep before the lockdown and the prevalence increased to 52.4% during the lockdown. A further cross-sectional study on 1826 Italian adults confirmed the impact of the lockdown on quality of sleep, that was especially evident among females, those with low education level, and those who experienced financial problems.

Vietnam

As of January 2021, Vietnam has largely returned to everyday life thanks to the government's success in effective communication to citizens, early development of testing kits, a robust contact tracing program, and containment based upon epidemiological risk rather than observable symptoms. By appealing to universal Vietnamese values such as tam giao, or the Three Teachings, the Vietnamese government has managed to encourage a culture that values public health with the utmost importance and maintains a level of fortitude and resolve in fighting the spread of COVID-19.[51] However, Vietnamese patients quarantining due to COVID-19 have reported psychological strain associated with the stigma of sickness, financial constraints, and guilt from contracting the virus. Frontline healthcare workers at Bach Mai Hospital in Hanoi quarantined for greater than three weeks reported comparatively poorer self-image and general attitude when compared to shorter term patients.[52]

Mental health aftercare

Academics have theorized that once the pandemic stabilizes or fully ends, supervisors should ensure that time is made to reflect on and learn from the experiences by first responders, essential workers, and the general population to create a meaningful narrative rather than focusing on the trauma. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has recommended the active monitoring of staff for issues such as PTSD, moral injuries, and other associated mental illness.[53]

A potential solution to continue mental health care during the pandemic is to provide mental health care through video-conferencing psychotherapy and internet interventions.[54] Although e-mental health has not been integrated as a regular part of mental health care practice due to the lack of its acceptance in the past,[55] this way was reviewed as effective in producing promising results for anxiety and mood disorders.[56]

Long-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health

According to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (IASC), there can be long-term consequences due to the coronavirus pandemic. Deterioration of social networks and economies, stigma towards survivors of COVID-19, possible higher anger and aggression of frontline workers and the government, possible anger and aggression against children, and possible mistrust of information provided by official authorities are some of the long-term consequences anticipated by the IASC.[3] In South Africa, where one in four young men between the ages of 14 years and 24 years reported current suicidal thoughts[57] even before the COVID-19 pandemic, one wonders what the future holds for their well-being.

Some of these consequences could be due to realistic dangers, but many reactions could be borne out of lack of knowledge, rumors, and misinformation.[58] It is also possible that some people may have positive experiences, such as pride about finding ways of coping. It is likely that community members show altruism and cooperation when faced with a crisis, and people might experience satisfaction from helping others.[59]

See also

References

[Costi, S.; Paltrinieri, S.; Bressi, B.; Fugazzaro, S.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Mazzini, E. 1]

- CDC (11 February 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Luo, Yang; Chua, Cher Rui; Xiong, Zhonghui; Ho, Roger C.; Ho, Cyrus S. H. (23 November 2020). "A Systematic Review of the Impact of Viral Respiratory Epidemics on Mental Health: An Implication on the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 565098. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565098. PMC 7719673. PMID 33329106.

- "Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial support" (PDF). MH Innovation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "OECD". read.oecd-ilibrary.org. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Jemberie, W. B.; Stewart Williams, J.; Eriksson, M.; Grönlund, A-S.; Ng, N.; Blom Nilsson, M.; Padyab, M.; Priest, K. C.; Sandlund, M.; Snellman, F.; McCarty, D.; Lundgren, L. M.; et al. (21 July 2020). "Substance Use Disorders and COVID-19: Multi-Faceted Problems Which Require Multi-Pronged Solutions". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 714. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00714. PMC 7396653. PMID 32848907. S2CID 220651117.

- De Man, Jeroen; Buffel, Veerle; van de Velde, Sarah; Bracke, Piet; Van Hal, Guido F.; Wouters, Edwin; Gadeyne, Sylvie; Kindermans, Hanne P. J.; Joos, Mathilde; Vanmaercke, Sander; van Studenten, Vlaamse Vereniging; Nyssen, Anne-Sophie; Puttaert, Ninon; Vervecken, Dries; Van Guyse, Marlies (7 January 2021). "Disentangling depression in Belgian higher education students amidst the first COVID-19 lockdown (April-May 2020)". Archives of Public Health. 79 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s13690-020-00522-y.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - "ICN COVID-19 Update: New guidance on mental health and psychosocial support will help to alleviate effects of stress on hard-pressed staff". ICN - International Council of Nurses. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Emergency Responders: Tips for taking care of yourself". emergency.cdc.gov. 10 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Chen, Qiongni; Liang, Mining; Li, Yamin; Guo, Jincai; Fei, Dongxue; Wang, Ling; He, Li; Sheng, Caihua; Cai, Yiwen; Li, Xiaojuan; Wang, Jianjian (1 April 2020). "Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak". The Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (4): e15–e16. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. ISSN 2215-0366. PMC 7129426. PMID 32085839.

- Liu, Shuai; Yang, Lulu; Zhang, Chenxi; Xiang, Yu-Tao; Liu, Zhongchun; Hu, Shaohua; Zhang, Bin (1 April 2020). "Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak". The Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (4): e17–e18. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. ISSN 2215-0366. PMC 7129099. PMID 32085841.

- Golberstein, Ezra; Wen, Hefei; Miller, Benjamin F. (14 April 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health for Children and Adolescents". JAMA Pediatrics. 174 (9): 819–820. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. PMID 32286618.

- Czeisler, Mark É (2020). "Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (32): 1049–1057. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 7440121. PMID 32790653.

- Taquet, Maxime; Luciano, Sierra; Geddes, John R; Harrison, Paul J (2020). "Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA". The Lancet Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30462-4. ISSN 2215-0366. PMID 33181098. S2CID 226846568.

- Katherine Rosman (3 April 2020). "For Those With O.C.D., a Threat That Is Both Heightened and Familiar". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Fineberg, N. A.; Van Ameringen, M.; Drummond, L.; Hollander, E.; Stein, D. J.; Geller, D.; Walitza, S.; Pallanti, S.; Pellegrini, L.; Zohar, J.; Rodriguez, C. I.; Menchon, J. M.; Morgado, P.; Mpavaenda, D.; Fontenelle, L. F.; Feusner, J. D.; Grassi, G.; Lochner, C.; Veltman, D. J.; Sireau, N.; Carmi, L.; Adam, D.; Nicolini, H.; Dell'Osso, B.; et al. (12 April 2020). "How to manage obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) under COVID-19: A clinician's guide from the International College of Obsessive Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (ICOCS) and the Obsessive-Compulsive Research Network (OCRN) of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 100: 152174. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152174. PMC 7152877. PMID 32388123.

- Pyrek, Emily (15 April 2020). "COVID-19 proving extra challenging for people with OCD and other mental health conditions". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Moore, Georgie (22 April 2020). "Battling anxiety in the age of COVID-19". Australian Associated Press. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Sparrow, Wendy (24 March 2020). "'COVID-19 Is Giving Everyone A Small Glimpse Of What It's Like To Live With OCD'". Women's Health. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Welch, Craig (15 April 2020). "Are we coping with social distancing? Psychologists are watching warily". National Geographic. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Zakarin, Jordan (2 April 2020). "A Pandemic Is Hell For Everyone, But Especially For Those With OCD". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Turay Jr., Ismail (28 March 2020). "COVID-19: Social distancing may affect one's mental health, experts say". Dayton Daily News. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Jain MD, Shaili (13 April 2020). "Bracing for an Epidemic of PTSD Among COVID-19 Workers". Psychology Today. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "UPMC psychologist discusses mental health impact of COVID-19 on patients with PTSD, trauma". WJAC 6. 25 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Aten Ph.D., Jamie D. (4 April 2020). "Are COVID-19 Patients at Risk for PTSD?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Liu, Jia Jia; Bao, Yanping; Huang, Xiaolin; Shi, Jie; Lu, Lin (1 May 2020). "Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19". The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 4 (5): 347–349. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. ISSN 2352-4642. PMC 7118598. PMID 32224303.

- Lee, Joyce (14 April 2020). "Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19". The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health. 4 (6): 421. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. ISSN 2352-4642. PMC 7156240. PMID 32302537.

- Saurabh, K., Ranjan, S. Compliance and Psychological Impact of Quarantine in Children and Adolescents due to COVID-19 Pandemic. Indian J Pediatr 87, 532–536 (2020). doi:10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3

- Aristovnik A, Keržič D, Ravšelj D, Tomaževič N, Umek L (October 2020). "Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective". Sustainability. 12 (20): 8438. doi:10.3390/su12208438.

- Rimmer, Abi (16 November 2020). "Sixty Seconds on . . . Wobble Rooms". BMJ. 371: m4461. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4461. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 33199290. S2CID 226966877.

- Gunnell, David; et al. (21 April 2020). "Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic". The Lancet. 7 (6): 468–471. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. PMC 7173821. PMID 32330430. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Baker, Noel (22 April 2020). "Warning Covid-19 could lead to spike in suicide rates". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- John, Ann; Pirkis, Jane; Gunnell, David; Appleby, Louis; Morrissey, Jacqui (12 November 2020). "Trends in suicide during the covid-19 pandemic". BMJ. 371: m4352. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4352. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 33184048. S2CID 226300218.

- Hilliard, Mark (27 April 2020). "'Cocooning' and mental health: Over 16,000 calls to Alone support line". The Irish Times. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Goh, Winni Zhou, Brenda (11 June 2020). "In post-lockdown China, student mental health in focus amid reported jump in suicides". Reuters. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "Two tipplers in Kerala commit suicide upset at not getting liquor during COVID-19 lockdown". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Ueda, Michiko; Nordström, Robert; Matsubayashi, Tetsuya (8 October 2020). "Suicide and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan". dx.doi.org. doi:10.1101/2020.10.06.20207530. S2CID 222307132. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "新型コロナウイルス感染症対策(こころのケア)|こころの耳:働く人のメンタルヘルス・ポータルサイト". kokoro.mhlw.go.jp. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Owatari, Misaki (20 September 2020). "〈独自〉女性の自殺急増 コロナ影響か 同様の韓国に異例の連絡". 産経ニュース (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Green, Erica (24 January 2021). "Surge of Student Suicides Pushes Las Vegas Schools to Reopen". New York Times.

- Jackson, Amanda (10 April 2020). "A crisis mental-health hotline has seen an 891% spike in calls". CNN. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Simon, Mallory (8 May 2020). "75,000 Americans at risk of dying from overdose or suicide due to coronavirus despair, group warns". CNN. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Well Being Trust & The Robert Graham Center Analysis. "The COVID Pandemic Could Lead to 75,000 Additional Deaths from Alcohol and Drug Misuse and Suicide". Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Marazziti, Donatella; Stahl, Stephen M. (June 2020). "The relevance of COVID-19 pandemic to psychiatry". World Psychiatry. 19 (2): 261. doi:10.1002/wps.20764. ISSN 1723-8617. PMC 7215065. PMID 32394565.

- Vijayaraghavan, Padhmanabhan; SINGHAL, DIVYA (13 April 2020). "A Descriptive Study of Indian General Public's Psychological responses during COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown Period in India". dx.doi.org. doi:10.31234/osf.io/jeksn. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Hawryluck, Laura; Gold, Wayne L.; Robinson, Susan; Pogorski, Stephen; Galea, Sandro; Styra, Rima (July 2004). "SARS Control and Psychological Effects of Quarantine, Toronto, Canada". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (7): 1206–1212. doi:10.3201/eid1007.030703. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3323345. PMID 15324539.

- Yamamoto, Tetsuya; Uchiumi, Chigusa; Suzuki, Naho; Yoshimoto, Junichiro; Murillo-Rodriguez, Eric (30 July 2020). "The psychological impact of 'mild lockdown' in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide survey under a declared state of emergency". MedRxiv: 2020.07.17.20156125. doi:10.1101/2020.07.17.20156125. S2CID 220601718.

- Sugaya, Nagisa; Yamamoto, Tetsuya; Suzuki, Naho; Uchiumi, Chigusa (29 October 2020). "A real-time survey on the psychological impact of mild lockdown for COVID-19 in the Japanese population". Scientific Data. 7 (1): 372. doi:10.1038/s41597-020-00714-9. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 7596049. PMID 33122626.

- Gualano, Maria Rosaria; Lo Moro, Giuseppina; Voglino, Gianluca; Bert, Fabrizio; Siliquini, Roberta (2 July 2020). "Effects of Covid-19 Lockdown on Mental Health and Sleep Disturbances in Italy". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (13): 4779. doi:10.3390/ijerph17134779. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 7369943. PMID 32630821.

- Small, Sean; Blanc, Judite (8 January 2021). "Mental Health During COVID-19: Tam Giao and Vietnam's Response". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 589618. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589618. ISSN 1664-0640.

- Do Duy, Cuong; Nong, Vuong Minh; Ngo Van, An; Doan Thu, Tra; Do Thu, Nga; Nguyen Quang, Tuan (October 2020). "COVID ‐19‐related stigma and its association with mental health of health‐care workers after quarantine in V ietnam". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 74 (10): 566–568. doi:10.1111/pcn.13120. ISSN 1323-1316. PMC 7404653. PMID 32779787.

- Greenberg, Neil; Docherty, Mary; Gnanapragasam, Sam; Wessely, Simon (26 March 2020). "Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic". BMJ. 368: m1211. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1211. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32217624.

- Wind, Tim R.; Rijkeboer, Marleen; Andersson, Gerhard; Riper, Heleen (1 April 2020). "The COVID-19 pandemic: The 'black swan' for mental health care and a turning point for e-health". Internet Interventions. 20: 100317. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2020.100317. ISSN 2214-7829. PMC 7104190. PMID 32289019.

- Topooco, Naira; Riper, Heleen; Araya, Ricardo; Berking, Matthias; Brunn, Matthias; Chevreul, Karine; Cieslak, Roman; Ebert, David Daniel; Etchmendy, Ernestina; Herrero, Rocío; Kleiboer, Annet (June 2017). "Attitudes towards digital treatment for depression: A European stakeholder survey". Internet Interventions. 8: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2017.01.001. ISSN 2214-7829. PMC 6096292. PMID 30135823.

- "Supplemental Material for Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction via Group Videoconferencing: Feasibility, Acceptability, Safety, and Efficacy". Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 14 September 2020. doi:10.1037/int0000216.supp. ISSN 1053-0479.

- Mngoma, Nomusa F.; Ayonrinde, Oyedeji A.; Fergus, Stevenson; Jeeves, Alan H.; Jolly, Rosemary J. (20 April 2020). "Distress, desperation and despair: anxiety, depression and, suicidality among rural South African youth". International Review of Psychiatry. 0: 1–11. doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1741846. ISSN 0954-0261. PMID 32310008.

- Tyler, Wat (8 May 2020). "The Bottomless Pit: Social Distancing, COVID-19 & The Bubonic Plague". Sandbox Watch. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Social Distancing: How To Keep Connected And Upbeat". SuperWellnessBlog. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- costi, stefania (2021). "Poor Sleep during the First Peak of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study". Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (1): 306. doi:10.3390/ijerph18010306. PMC 7795804. PMID 33406588.

- Costi, S.; Paltrinieri, S.; Bressi, B.; Fugazzaro, S.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Mazzini, E. (2021). "Poor Sleep during the First Peak of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. 18, 306". Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (1): 306. doi:10.3390/ijerph18010306. PMC 7795804. PMID 33406588 – via https://iris.unimore.it/simple-search?query=costi+stefania.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)