Treatment and management of COVID-19

There is no specific, effective treatment or cure for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.[1][2] Thus, the cornerstone of management of COVID-19 is supportive care, which includes treatment to relieve symptoms, fluid therapy, oxygen support and prone positioning as needed, and medications or devices to support other affected vital organs.[3][4][5]

Most cases of COVID-19 are mild. In these, supportive care includes medication such as paracetamol or NSAIDs to relieve symptoms (fever, body aches, cough), proper intake of fluids, rest, and nasal breathing.[6][2][7][8] Good personal hygiene and a healthy diet are also recommended.[9] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that those who suspect they are carrying the virus isolate themselves at home and wear a face mask.[10]

People with more severe cases may need treatment in hospital. In those with low oxygen levels, use of the glucocorticoid dexamethasone is strongly recommended, as it can reduce the risk of death.[11][12][13] Noninvasive ventilation and, ultimately, admission to an intensive care unit for mechanical ventilation may be required to support breathing.[14] Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used to address the issue of respiratory failure, but its benefits are still under consideration.[15][16]

Several experimental treatments are being actively studied in clinical trials.[1] Others were thought to be promising early in the pandemic, such as hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir, but later research found them to be ineffective or even harmful.[1][17][18] Despite ongoing research, there is still not enough high-quality evidence to recommend so-called early treatment.[17][18] Nevertheless, in the United States, two monoclonal antibody-based therapies are available for early use in cases thought to be at high risk of progression to severe disease.[18] The antiviral remdesivir is available in the U.S., Canada, Australia, and several other countries, with varying restrictions; however, it is not recommended for people needing mechanical ventilation, and is discouraged altogether by the World Health Organization (WHO),[19] due to limited evidence of its efficacy.[1]

Some people may experience persistent symptoms or disability after recovery from the infection; this is known as long COVID. There is still limited information on the best management and rehabilitation for this condition.[14]

The WHO, the Chinese National Health Commission, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the United States' National Institutes of Health, among other bodies and agencies worldwide, have all published recommendations and guidelines for taking care of people with COVID‑19.[20][21][14][22] Intensivists and pulmonologists in the U.S. have compiled treatment recommendations from various agencies into a free resource, the IBCC.[23][24]

Medications

As of January 2021, dexamethasone is the only medication with proven clinical benefit in treating COVID-19, as determined in randomized controlled trials, with some low-certainty evidence to support remdesivir.[1][25][26] Early research suggested a benefit of remdesivir in preventing death and shortening illness duration, but this was not borne out by subsequent trials.[1]

Taking over-the-counter drugs such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, drinking fluids, and resting may help alleviate symptoms.[2][27][28] Depending on the severity, oxygen therapy and intravenous fluids may be required.[29]

Several potentially disease-modifying treatments have been investigated and found to be ineffective or unsafe, and are thus not recommended for use; these include baloxavir marboxil, favipiravir, lopinavir/ritonavir, ruxolitinib, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, interferon β-1a, and colchicine.[13]

Systemic corticosteroids

Dexamethasone may be used, but is only helpful in people requiring supplemental oxygen. Following an analysis of seven randomized trials,[30] the WHO recommends the use of systemic corticosteroids in guidelines for treatment of people with severe or critical illness, and that they not be used in people that do not meet the criteria for severe illness.[31]

The use of corticosteroids can cause a severe and deadly "hyperinfection" syndrome for people with strongyloidiasis, which may be an underlying condition in populations exposed to the parasite Strongyloides stercoralis. This risk can be mitigated by the presumptive use of ivermectin before steroid treatment.[32]

Remdesivir

Emergency use authorization for remdesivir was granted in the U.S. on May 2020 for people hospitalized with severe COVID-19.[33][34] The interim authorization was granted considering the lack of other specific treatments, and that its potential benefits appeared to outweigh the potential risks.[33][35][36] In September 2020, following a review of later research, the WHO recommended that remdesivir not be used for any cases of COVID-19, as there was no good evidence of benefit.[11]

In November 2020, the FDA issued a further emergency use authorization (EUA) for the combination of remdesivir with baricitinib (see below) for the treatment of suspected or laboratory confirmed COVID-19 in hospitalized people two years of age or older requiring supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).[37] The data supporting the EUA for baricitinib combined with remdesivir were based on a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (ACTT-2), which was conducted by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).[37]

Immunomodulation

In January 2021 in the United Kingdom, the National Health Service issued guidance that the immune modulating drugs tocilizumab and sarilumab were beneficial when given promptly to people with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care, following research which found a reduction in the risk of death by 24%.[38]

The oral JAK inhibitor baricitinib is also being studied for COVID-19 treatment.[39] In November 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorization for baricitinib to be given to certain people hospitalized with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (specifically, adults and children two years of age or older requiring supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or ECMO), but only in conjunction with remdesivir.[40] In a single clinical trial, this combination therapy was shown to have a small, but statistically significant effect on patient outcomes compared to administration of remdesivir alone.[41]

Other disease-modifying treatments

Medications to prevent blood clotting have been suggested for treatment, and anticoagulant therapy with low molecular weight heparin appears to be associated with better outcomes in severe COVID‐19 showing signs of coagulopathy (elevated D-dimer).[42]

In November 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for the investigational monoclonal antibody therapies bamlanivimab[43] and casirivimab/imdevimab for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in outpatients.[44] Nevertheless, the NIH Treatment Guidelines state that there is still insufficient evidence to recommend either for or against the use of bamlanivimab and casirivimab?imdevimab.[14]

Respiratory support

.jpg.webp)

Mechanical ventilation

Most cases of COVID‑19 are not severe enough to require mechanical ventilation or alternatives, but a percentage of cases are.[45][46] The type of respiratory support for individuals with COVID‑19 related respiratory failure is being actively studied for people in the hospital, with some evidence that intubation can be avoided with a high flow nasal cannula or bi-level positive airway pressure.[47] Whether either of these two leads to the same benefit for people who are critically ill is not known.[48] Some doctors prefer staying with invasive mechanical ventilation when available because this technique limits the spread of aerosol particles compared to a high flow nasal cannula.[45]

Mechanical ventilation had been performed in 79% of critically ill people in hospital including 62% who previously received other treatment. Of these 41% died, according to one study in the United States.[49]

Severe cases are most common in older adults (those older than 60 years,[45] and especially those older than 80 years).[50] Many developed countries do not have enough hospital beds per capita, which limits a health system's capacity to handle a sudden spike in the number of COVID‑19 cases severe enough to require hospitalisation.[51] This limited capacity is a significant driver behind calls to flatten the curve.[51] One study in China found 5% were admitted to intensive care units, 2.3% needed mechanical support of ventilation, and 1.4% died.[15] In China, approximately 30% of people in hospital with COVID‑19 are eventually admitted to ICU.[52]

The administration of inhaled nitric oxide to people being ventilated is not recommended, and evidence around this practice is weak.[53]

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Mechanical ventilation becomes more complex as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) develops in COVID‑19 and oxygenation becomes increasingly difficult.[54] Ventilators capable of pressure control modes and high PEEP[55] are needed to maximise oxygen delivery while minimising the risk of ventilator-associated lung injury and pneumothorax.[56]

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an artificial lung technology that has been used since the 1980s to treat respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome when conventional mechanical ventilation fails. In this complex procedure, blood is removed from the body via large cannulae, moved through a membrane oxygenator that performs the lung functions of oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide removal, and then returned to the body. The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) maintains a registry of outcomes for this technology, and it has been used in >120,000 patients over 435 ECMO centers worldwide with 40% mortality for adult respiratory patients.[57]

Initial use of ECMO in COVID-19 patients from China early in the pandemic suggested poor outcomes, with >90% mortality.[58] In March 2020, the ELSO registry began collecting data on the worldwide use of ECMO for patients with COVID-19 and reporting this data on the ELSO website in real time. In September 2020, the outcomes of 1,035 COVID-19 patients supported with ECMO from 213 experienced centers in 36 different countries were published in The Lancet, and demonstrated 38% mortality, which is similar to many other respiratory diseases treated with ECMO. The mortality is also similar to the 35% mortality seen in the EOLIA trial, the largest randomized controlled trial for ECMO in ARDS.[59] This registry based, multi-center, multi-country data provide provisional support for the use of ECMO for COVID-19 associated acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Given that this is a complex technology that can be resource intense, guidelines exist for the use of ECMO during the COVID-19 pandemic.[60][61][62]

Prevention of onward transmission

Self-isolation has been recommended for people with mild cases of COVID-19 or who suspect they have been infected, even those with nonspecific symptoms, to prevent onward transmission of the virus and help reduce the burden on health care facilities.[2] In many jurisdictions, such as the United Kingdom, this is required by law.[64] Guidelines on self-isolation vary by country; the U.S. CDC and UK National Health Service have issued specific instructions, as have other local authorities.[65][64]

Adequate ventilation, cleaning and disinfection, and waste disposal are also essential to prevent further spread of infection.[27]

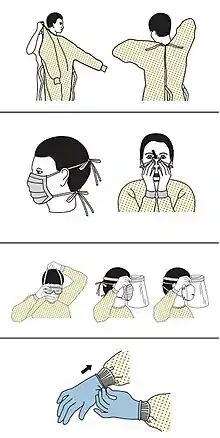

Personal protective equipment

Precautions must be taken to minimise the risk of virus transmission, especially in healthcare settings when performing procedures that can generate aerosols, such as intubation or hand ventilation.[66] For healthcare professionals caring for people with COVID‑19, the CDC recommends placing the person in an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) in addition to using standard precautions, contact precautions, and airborne precautions.[67]

The CDC outlines the guidelines for the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the pandemic. The recommended gear is a PPE gown, respirator or facemask, eye protection, and medical gloves.[68][69]

When available, respirators (instead of face masks) are preferred.[70] CDC recommends mask use in public places, when not able to social distance, and while interacting with people outside of those that the person lives with.[71] N95 respirators are approved for industrial settings but the FDA has authorized the masks for use under an emergency use authorization (EUA). They are designed to protect from airborne particles like dust but effectiveness against a specific biological agent is not guaranteed for off-label uses.[72] When masks are not available, the CDC recommends using face shields or, as a last resort, homemade masks.[73]

Psychological support

Individuals may experience distress from quarantine, travel restrictions, side effects of treatment, or fear of the infection itself. To address these concerns, the National Health Commission of China published a national guideline for psychological crisis intervention on 27 January 2020.[74][75]

The Lancet published a 14-page call for action focusing on the UK and stated conditions were such that a range of mental health issues was likely to become more common. BBC quoted Rory O'Connor in saying, "Increased social isolation, loneliness, health anxiety, stress, and an economic downturn are a perfect storm to harm people's mental health and wellbeing."[76][77]

Special populations

Concurrent treatment of other conditions

Early in the pandemic, theoretical concerns were raised about ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. However, later research found no evidence to justify stopping these medications in people who take them for conditions such as high blood pressure.[14][78][79][80] One study from 22 April found that people with COVID‑19 and hypertension had lower all-cause mortality when on these medications.[81] Similar concerns were raised about non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen; these were likewise not borne out, and NSAIDs may both be used to relieve symptoms of COVID-19 and continue to be used by people who take them for other conditions.[82]

People who use topical or systemic corticosteroids for respiratory conditions such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should continue taking them as prescribed even if they contract COVID-19.[25]

During pregnancy

To date, most SARS-CoV-2-related clinical trials have excluded, or included only a few, pregnant or lactating women. This limitation makes it difficult to make evidence-based therapy recommendations in these patients and potentially limits their COVID-19 treatment options. The US CDC recommends shared decision-making between the patient and the clinical team when treating pregnant women with investigational medication.[83]

Clinical research and experimental treatments

Several antiviral drugs are under investigation for COVID-19, though none has yet been shown to be clearly effective on mortality in published randomized controlled trials.[84] The safety and effectiveness of convalescent plasma as a treatment option requires further research.[85] Other trials are investigating whether existing medications can be used effectively against the body's immune reaction to SARS-CoV-2 infection.[84][86]

Antiviral medications

Research into potential treatments started in January 2020,[87] and several antiviral drugs are in clinical trials.[88][89] Although new medications may take until 2021 to develop,[90] several of the medications being tested are already approved for other uses or are already in advanced testing.[91] Antiviral medication may be tried in people with severe disease.[3] The WHO recommended volunteers take part in trials of the effectiveness and safety of potential treatments.[92]

Passive immunization

Passive immunization with convalescent plasma or hyperimmune serum has been proposed as a potential treatment for COVID-19.[93]

In the United States, the FDA has granted temporary authorization to convalescent plasma (plasma from the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19, which thus contains antibodies against SARS-CoV-2) as an experimental treatment in cases where the person's life is seriously or immediately threatened.[94] However, convalescent plasma treatment has not undergone the randomized controlled or non-randomized clinical studies needed to determine if is safe and effective for treating people with COVID-19.[93][95][96]

Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico have pursued development of antisera.[97] Brazil began development of an equine hyperimmune serum, obtained by inoculating horses with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, in mid-2020. A consortium of Instituto Vital Brazil, UFRJ, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and the D’Or Institute for Research and Education in Rio de Janeiro began preclinical trials in May 2020,[98] while Instituto Butantan in São Paulo completed animal testing in September.[97] In December 2020, Argentina granted emergency authorization to CoviFab, a locally developed formulation of equine hyperimmune serum, for use in cases of moderate to severe COVID-19, based on the initial results of a single phase 2/3 trial which suggested reductions in mortality, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation requirements in patients who received the serum.[99][100] This was harshly criticized by the Argentine Intensive Care Society, which stated that the trial failed to achieve its primary or secondary endpoints and did not demonstrate any statistically significant differences between the serum and placebo groups.[100]

Vitamin D

There has been particular interest given the significant overlap in the risk factors for severe COVID-19 and vitamin D deficiency, including obesity, older age, and Black or Asian ethnic origin, noting that vitamin D deficiency is common in Europe and the United States particularly within these groups.[101] The general recommendation to take vitamin D supplements, particularly given the levels of vitamin D deficiency in Western populations, has been repeated.[102]

There are a number of clinical trials being undertaken to examine any specific role for vitamin D in COVID-19 prevention and management.[103] Emerging results indicate a link between vitamin D deficiency and the severity of the disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 27 publications found that, although vitamin D deficiency was not associated with a higher probability of becoming infected with COVID-19, there were significant associations between vitamin D deficiency and the severity of the disease, including relative increases in hospitalization and mortality rates of about 80%.[104] As of October 2020 there has been no advisory recommendation to use vitamin D or its metabolites specifically for COVID-19 therapy.[102]

References

- Siemieniuk, Reed AC; Bartoszko, Jessica J; Ge, Long; Zeraatkar, Dena; Izcovich, Ariel; Kum, Elena; Pardo-Hernandez, Hector; Rochwerg, Bram; Lamontagne, Francois; Han, Mi Ah; Liu, Qin; Agarwal, Arnav; Agoritsas, Thomas; Chu, Derek K; Couban, Rachel; Darzi, Andrea; Devji, Tahira; Fang, Bo; Fang, Carmen; Flottorp, Signe Agnes; Foroutan, Farid; Ghadimi, Maryam; Heels-Ansdell, Diane; Honarmand, Kimia; Hou, Liangying; Hou, Xiaorong; Ibrahim, Quazi; Khamis, Assem; Lam, Bonnie; Loeb, Mark; Marcucci, Maura; McLeod, Shelley L; Motaghi, Sharhzad; Murthy, Srinivas; Mustafa, Reem A; Neary, John D; Qasim, Anila; Rada, Gabriel; Riaz, Irbaz Bin; Sadeghirad, Behnam; Sekercioglu, Nigar; Sheng, Lulu; Sreekanta, Ashwini; Switzer, Charlotte; Tendal, Britta; Thabane, Lehana; Tomlinson, George; Turner, Tari; Vandvik, Per O; Vernooij, Robin WM; Viteri-García, Andrés; Wang, Ying; Yao, Liang; Ye, Zhikang; Guyatt, Gordon H; Brignardello-Petersen, Romina (2020-07-30). "Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis". BMJ. BMJ: m2980. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2980. ISSN 1756-1833.

- "Coronavirus". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- Fisher D, Heymann D (February 2020). "Q&A: The novel coronavirus outbreak causing COVID-19". BMC Medicine. 18 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01533-w. PMC 7047369. PMID 32106852.

- Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, et al. (May 2020). "Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province". Chinese Medical Journal. 133 (9): 1025–1031. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. PMC 7147277. PMID 32044814.

- Wang T, Du Z, Zhu F, Cao Z, An Y, Gao Y, Jiang B (March 2020). "Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19". Lancet. Elsevier BV. 395 (10228): e52. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30558-4. PMC 7270177. PMID 32171074.

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q (March 2020). "Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures". Journal of Medical Virology. n/a (n/a): 568–576. doi:10.1002/jmv.25748. PMC 7228347. PMID 32134116.

- Martel J, Ko YF, Young JD, Ojcius DM (May 2020). "Could nasal breathing help to mitigate the severity of COVID-19". Microbes and Infection. 22 (4–5): 168–171. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.002. PMC 7200356. PMID 32387333.

- "Coronavirus recovery: breathing exercises". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Wang L, Wang Y, Ye D, Liu Q (March 2020). "Review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on current evidence". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 55 (6): 105948. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948. PMC 7156162. PMID 32201353. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5 April 2020). "What to Do if You Are Sick". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Update to living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 371: m4475. Nov 19, 2020. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4475. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 33214213. S2CID 227059995.

- "Q&A: Dexamethasone and COVID-19". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Home". National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines". www.nih.gov. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. (April 2020). "Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China". The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 382 (18): 1708–1720. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2002032. PMC 7092819. PMID 32109013.

- Henry BM (April 2020). "COVID-19, ECMO, and lymphopenia: a word of caution". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. Elsevier BV. 8 (4): e24. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30119-3. PMC 7118650. PMID 32178774.

- Kim, Peter S.; Read, Sarah W.; Fauci, Anthony S. (2020-12-01). "Therapy for Early COVID-19". JAMA. American Medical Association (AMA). 324 (21): 2149. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.22813. ISSN 0098-7484.

- "COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines". www.nih.gov. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2021-01-18./

- Hsu, Jeremy (2020-11-19). "Covid-19: What now for remdesivir?". BMJ. BMJ: m4457. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4457. ISSN 1756-1833.

- "Clinical management of COVID-19". World Health Organization (WHO). 2020-05-27. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) | NICE". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- Cheng ZJ, Shan J (April 2020). "2019 Novel coronavirus: where we are and what we know". Infection. 48 (2): 155–163. doi:10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y. PMC 7095345. PMID 32072569.

- Farkas J (March 2020). COVID-19—The Internet Book of Critical Care (digital) (Reference manual). USA: EMCrit. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "COVID19—Resources for Health Care Professionals". Penn Libraries. 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Australian guidelines for the clinical care of people with COVID-19". National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Rizk, John G.; Kalantar-Zadeh, Kamyar; Mehra, Mandeep R.; Lavie, Carl J.; Rizk, Youssef; Forthal, Donald N. (2020-07-21). "Pharmaco-Immunomodulatory Therapy in COVID-19". Drugs. Springer. 80 (13): 1267–1292. doi:10.1007/s40265-020-01367-z. ISSN 0012-6667.

- "Home care for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and management of their contacts" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- "Prevention & Treatment". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2020-02-15. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Overview of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)—Summary of relevant conditions". The BMJ. Archived from the original on 2020-01-31. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- Sterne JA, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, et al. (October 2020). "Association Between Administration of Systemic Corticosteroids and Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: A Meta-analysis". JAMA. 324 (13): 1330–1341. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.17023. PMID 32876694.

- "Corticosteroids for COVID-19", Living Guidance, WHO, 2 September 2020, retrieved 2020-09-02

- "A parasitic infection that can turn fatal with administration of corticosteroids". WHO. 17 December 2021.

- "Remdesivir EUA Letter of Authorization" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

To only treat adults and children with suspected or laboratory confirmed COVID-19 and severe disease defined as SpO2 94% on room air, requiring supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Rizk, John G.; Forthal, Donald N.; Kalantar-Zadeh, Kamyar; Mehra, Mandeep R.; Lavie, Carl J.; Rizk, Youssef; Pfeiffer, JoAnn P.; Lewin, John C. (November 2020). "Expanded Access Programs, compassionate drug Use, and Emergency Use Authorizations during the COVID-19 pandemic". Drug Discovery Today. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2020.11.025. PMC 7694556. PMID 33253920.

- "Frequently Asked Questions on the Emergency Use Authorization for Remdesivir for Certain Hospitalized COVID‐19 Patients" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "NIH Clinical Trial Shows Remdesivir Accelerates Recovery from Advanced COVID-19". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Drug Combination for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Press release). 19 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Arthritis drugs effective in improving survival in sickest COVID-19 patients". National Institute of Health Research. 7 January 2021.

- Favalli, Ennio G; Biggioggero, Martina; Maioli, Gabriella; Caporali, Roberto (September 2020). "Baricitinib for COVID-19: a suitable treatment?". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 20 (9): 1012–1013. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30262-0. ISSN 1473-3099. PMC 7270794. PMID 32251638.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Drug Combination for Treatment of COVID-19" (Press release). FDA. 19 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- "Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Baricitinib" (PDF). Indianapolis: Ely Lilly and Company. 19 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z (May 2020). "Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 18 (5): 1094–1099. doi:10.1111/jth.14817. PMID 32220112.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Monoclonal Antibody for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Press release). 9 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA (March 2020). "Care for Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19". JAMA. 323 (15): 1499–1500. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3633. PMID 32159735. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- World Health Organization (28 January 2020). "Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Wang K, Zhao W, Li J, Shu W, Duan J (March 2020). "The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China". Annals of Intensive Care. 10 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z. PMC 7104710. PMID 32232685.

- McEnery T, Gough C, Costello RW (April 2020). "COVID-19: Respiratory support outside the intensive care unit". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 8 (6): 538–539. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30176-4. PMC 7146718. PMID 32278367.

- Cummings, Matthew J.; Baldwin, Matthew R.; Abrams, Darryl; Jacobson, Samuel D.; Meyer, Benjamin J.; Balough, Elizabeth M.; Aaron, Justin G.; Claassen, Jan; Rabbani, LeRoy E.; Hastie, Jonathan; Hochman, Beth R. (19 May 2020). "Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study". The Lancet. 0 (10239): 1763–1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7237188. PMID 32442528.

- Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Imai N, Ainslie K, Baguelin M (16 March 2020). Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand (Report). Imperial College London. Table 1. doi:10.25561/77482. hdl:20.1000/100. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Scott, Dylan (16 March 2020). "Coronavirus is exposing all of the weaknesses in the US health system High health care costs and low medical capacity made the US uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus". Vox. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 6 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, et al. (May 2020). "Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Intensive Care Med (Clinical practice guideline). 46 (5): 854–887. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. PMID 32222812.

- Matthay MA, Aldrich JM, Gotts JE (May 2020). "Treatment for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 8 (5): 433–434. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30127-2. PMC 7118607. PMID 32203709.

- Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, Brower RG, Talmor D, Walter SD, et al. (March 2010). "Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 303 (9): 865–73. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.218. PMID 20197533.

- Diaz R, Heller D (2020). Barotrauma And Mechanical Ventilation. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31424810.

- "Extracorporeal Life Support Organization - ECMO and ECLS > Registry > Statistics > International Summary". www.elso.org. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- Henry, Brandon Michael; Lippi, Giuseppe (2020-08-01). "Poor survival with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Pooled analysis of early reports". Journal of Critical Care. 58: 27–28. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.011. ISSN 0883-9441. PMC 7118619. PMID 32279018.

- Combes, Alain; Hajage, David; Capellier, Gilles; Demoule, Alexandre; Lavoué, Sylvain; Guervilly, Christophe; Da Silva, Daniel; Zafrani, Lara; Tirot, Patrice; Veber, Benoit; Maury, Eric (2018-05-24). "Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (21): 1965–1975. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 29791822. S2CID 44106489.

- Bartlett, Robert H.; Ogino, Mark T.; Brodie, Daniel; McMullan, David M.; Lorusso, Roberto; MacLaren, Graeme; Stead, Christine M.; Rycus, Peter; Fraser, John F.; Belohlavek, Jan; Salazar, Leonardo (May 2020). "Initial ELSO Guidance Document: ECMO for COVID-19 Patients with Severe Cardiopulmonary Failure". ASAIO Journal. 66 (5): 472–474. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000001173. ISSN 1058-2916. PMC 7273858. PMID 32243267.

- Shekar, Kiran; Badulak, Jenelle; Peek, Giles; Boeken, Udo; Dalton, Heidi J.; Arora, Lovkesh; Zakhary, Bishoy; Ramanathan, Kollengode; Starr, Joanne; Akkanti, Bindu; Antonini, M. Velia (July 2020). "Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Coronavirus Disease 2019 Interim Guidelines: A Consensus Document from an International Group of Interdisciplinary Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Providers". ASAIO Journal. 66 (7): 707–721. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000001193. ISSN 1058-2916. PMC 7228451. PMID 32358233.

- Ramanathan, Kollengode; Antognini, David; Combes, Alain; Paden, Matthew; Zakhary, Bishoy; Ogino, Mark; MacLaren, Graeme; Brodie, Daniel; Shekar, Kiran (May 2020). "Planning and provision of ECMO services for severe ARDS during the COVID-19 pandemic and other outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 8 (5): 518–526. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30121-1. ISSN 2213-2600. PMC 7102637. PMID 32203711.

- "Sequence for Putting On Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "When to self-isolate and what to do - Coronavirus (COVID-19)". NHS. 2021-01-08. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021-01-07). "Isolate If You Are Sick". CDC. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- Cheung JC, Ho LT, Cheng JV, Cham EY, Lam KN (April 2020). "Staff safety during emergency airway management for COVID-19 in Hong Kong". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 8 (4): e19. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30084-9. PMC 7128208. PMID 32105633.

- "What healthcare personnel should know about caring for patients with confirmed or possible coronavirus disease 2" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 12 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- CDC (2020-02-11). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Frequently Asked Questions". Food and Drug Administration.

- "Strategies for Optimizing the Supply of Facemasks". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, Ng CH (March 2020). "Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (3): 228–229. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. PMC 7128153. PMID 32032543.

- Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. (March 2020). "The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (3): e14. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. PMC 7129673. PMID 32035030.

- Coronavirus: 'Profound' mental health impact prompts calls for urgent research, BBC, Philippa Roxby, 16 April 2020.

- Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID‑19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science, The Lancet, Emily Holmes, Rory O'Connor, Hugh Perry, et al., 15 April 2020, page 1: "A fragmented research response, characterised by small-scale and localised initiatives, will not yield the clear insights necessary to guide policymakers or the public."

- "Patients taking ACE-i and ARBs who contract COVID-19 should continue treatment, unless otherwise advised by their physician". Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "Patients taking ACE-i and ARBs who contract COVID-19 should continue treatment, unless otherwise advised by their physician". American Heart Association (Press release). 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- de Simone G. "Position Statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension on ACE-Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers". Council on Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "New Evidence Concerning Safety of ACE Inhibitors, ARBs in COVID-19". Pharmacy Times. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (19 March 2020). "FDA advises patients on use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for COVID-19". Drug Safety and Availability. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines" (PDF). CDC. Centers for Disease control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB (April 2020). "Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review". JAMA. 323 (18): 1824–1836. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6019. PMID 32282022. S2CID 215752785.

- Chai, Khai Li; Valk, Sarah J.; Piechotta, Vanessa; Kimber, Catherine; Monsef, Ina; Doree, Carolyn; Wood, Erica M.; Lamikanra, Abigail A.; Roberts, David J.; McQuilten, Zoe; So-Osman, Cynthia (12 October 2020). "Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD013600. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 33044747.

- McCreary EK, Pogue JM (April 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 Treatment: A Review of Early and Emerging Options". Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 7 (4): ofaa105. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa105. PMC 7144823. PMID 32284951.

- "Chinese doctors using plasma therapy on coronavirus, WHO says 'very valid' approach". Reuters. 17 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Steenhuysen J, Kelland K (24 January 2020). "With Wuhan virus genetic code in hand, scientists begin work on a vaccine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Duddu P (19 February 2020). "Coronavirus outbreak: Vaccines/drugs in the pipeline for Covid-19". clinicaltrialsarena.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020.

- Lu H (March 2020). "Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Bioscience Trends. 14 (1): 69–71. doi:10.5582/bst.2020.01020. PMID 31996494.

- Li G, De Clercq E (March 2020). "Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 19 (3): 149–150. doi:10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. PMID 32127666.

- Nebehay S, Kelland K, Liu R (5 February 2020). "WHO: 'no known effective' treatments for new coronavirus". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Chai KL, Valk SJ, Piechotta V, Kimber C, Monsef I, Doree C, Wood EM, Lamikanra AA, Roberts DJ, McQuilten Z, So-Osman C, Estcourt LJ, Skoetz N (October 2020). "Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD013600. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub3. PMID 33044747.

- "FDA now allows treatment of life-threatening COVID-19 cases using blood from patients who have recovered". TechCrunch. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Blood plasma taken from covid-19 survivors might help patients fight off the disease". MIT Technology Review.

- "Trials of Plasma From Recovered Covid-19 Patients Have Begun". Wired.

- Fioravanti C (2020-12-14). "Butantan desenvolve soro contra coronavírus" [Butantan develops serum against coronavirus]. Revista Pesquisa Fapesp (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Monnerat A (2021-01-04). "Vital Brazil desenvolve soro contra covid-19, mas medicamento ainda não foi testado em humanos" [Vital Brazil develops serum against COVID-19, but drug has yet to be tested in humans]. O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Argentina aprueba uso de suero equino que reduce en un 45% las muertes por COVID-19" [Argentina approves use of equine serum which reduces COVID-19 deaths by 45%] (in Spanish). Deutsche Welle. 2021-01-11. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Coronavirus: terapistas rechazaron "fuertemente" el uso de suero equino en pacientes graves" [Coronavirus: medics "strongly" reject use of equine serum in severe patients]. Clarín (in Spanish). 2021-01-17. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Martineau, AR; Forouhi, NG (September 2020). "Vitamin D for COVID-19: a case to answer?". The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 8 (9): 735–736. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30268-0. PMC 7398646. PMID 32758429.

- "Advisory statement on likely place in therapy | COVID-19 rapid evidence summary: vitamin D for COVID-19 | Advice | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Quesada-Gomez JM, Entrenas-Castillo M, Bouillon R (September 2020). "Vitamin D receptor stimulation to reduce acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients with coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 infections: Revised Ms SBMB 2020_166". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 202: 105719. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105719. PMC 7289092. PMID 32535032.

- Pereira M, Dantas Damascena A, Galvão Azevedo LM, de Almeida Oliveira T, da Mota Santana J (November 2020). "Vitamin D deficiency aggravates COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition: 1–9. doi:10.1080/10408398.2020.1841090. PMID 33146028.

External links

Treatment guidelines

- "JHMI Clinical Recommendations for Available Pharmacologic Therapies for COVID-19" (PDF). The Johns Hopkins University.

- "Bouncing Back From COVID-19: Your Guide to Restoring Movement" (PDF). The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

- "Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients with COVID-19" (PDF). Infectious Diseases Society of America. Lay summary.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines" (PDF). National Institutes of Health. Lay summary.

- World Health Organization. Corticosteroids for COVID-19: living guidance, 2 September 2020 (Report). hdl:10665/334125. WHO/2019-nCoV/Corticosteroids/2020.1. Lay summary.

- World Health Organization (2020). Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline, 17 December 2020 (Report). hdl:10665/337876. WHO/2019-nCoV/therapeutics/2020.1. Lay summary.

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Treatment and management of COVID-19 |