Prince George's County, Maryland

Prince George's County (often shortened to PG County)[2][3] is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland, bordering the eastern portion of Washington, D.C. As of the 2010 U.S. Census, the population was 863,420,[5] making it the second-most populous county in Maryland, behind Montgomery County. Its county seat is Upper Marlboro.[6] It is the largest and one of the most affluent African American-majority counties in the United States, with five of its communities identified in a 2015 top ten list.[7][8]

Prince George's County | |

|---|---|

| Prince George's County, Maryland[1] | |

.jpg.webp)  .jpg.webp)  | |

Seal Logo | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): "Semper Eadem" (English: "Ever the Same") | |

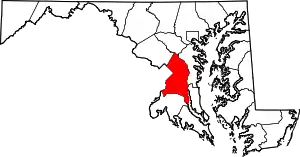

Location within the U.S. state of Maryland | |

Maryland's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 38°50′N 76°51′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | April 23, 1696[4] |

| Named for | Prince George of Denmark |

| Seat | Upper Marlboro |

| Largest city | Bowie |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Angela D. Alsobrooks (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 499 sq mi (1,290 km2) |

| • Land | 483 sq mi (1,250 km2) |

| • Water | 16 sq mi (40 km2) 3.2%% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 863,420 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 909,327 |

| • Density | 1,700/sq mi (670/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Prince Georgian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 20607–20774 |

| Area code | 240, 301 |

| Congressional districts | 4th, 5th |

| Website | www |

Prince George's County is included in the Washington metropolitan area. The county also hosts many federal governmental facilities, such as Joint Base Andrews and the United States Census Bureau headquarters.

Etymology

The official name of the county, as specified in the county's charter, is "Prince George’s County, Maryland".[9] The county is named after Prince George of Denmark (1653–1708), the consort of Anne, Queen of Great Britain, and the brother of King Christian V of Denmark and Norway. The county's demonym is Prince Georgian, and its motto is Semper Eadem (English: "Ever the Same"), a phrase used by Queen Anne. Prince George's County is frequently referred to as "PG" or "PG County", an abbreviation which is the subject of debate, some residents viewing it as a pejorative and others holding neutral feelings toward the term or even preferring the abbreviation over the full name.[2]

History

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

The Cretaceous Era brought dinosaurs to the area which left fossils now preserved in a 7.5-acre (3.0 ha) park in Laurel.[10] The site, which among other finds has yielded fossilized teeth from Astrodon and Priconodon species, has been called the most prolific in the eastern United States.[11]

In the mid to late Holocene era, the area was occupied by Paleo-Native Americans and then later, Native Americans. When the first European settlers arrived, what is now Prince George's County was inhabited by people of the Piscataway Indian Nation. Three branches of the tribe are still living today, two of which are headquartered in Prince George's County.[12]

17th century

Prince George's County was created by the English Council of Maryland in the Province of Maryland in April 1696[13] from portions of Charles and Calvert counties. The county was divided into six districts referred to as "Hundreds": Mattapany, Petuxant, Collington, Mount Calvert, Piscattoway and New Scotland.[13]

18th century

A portion was detached in 1748 to form Frederick County. Because Frederick County was subsequently divided to form the present Allegany, Garrett, Montgomery, and Washington counties, all of these counties in addition were derived from what had up to 1748 been Prince George's County.

In 1791, portions of Prince George's County were ceded to form the new District of Columbia (along with portions of Montgomery County, Maryland and parts of Northern Virginia that were later returned to Virginia).

19th century

During the War of 1812, the British marched through the county by way of Bladensburg to burn the White House. On their return, they kidnapped a prominent doctor, William Beanes. Lawyer Francis Scott Key was asked to negotiate for his release, which resulted in his writing "The Star-Spangled Banner".

Since much of the southern part of the county was tobacco farms that were worked by enslaved Africans,[14] there was a high population of African Americans in the region. After the Civil War, many African Americans attempted to become part of Maryland politics, but were met with violent repression after the fall of Reconstruction.[15]

In April 1865, John Wilkes Booth made his escape through Prince George's County while en route to Virginia after shooting President Abraham Lincoln.

20th century

The proportion of African Americans declined during the first half of the 20th century, but was renewed to over 50% in the early 1990s when the county again became majority African American.[16] The first African American County Executive was Wayne K. Curry, elected in 1994.

On July 1, 1997, the Prince George's County section of the city of Takoma Park, which straddled the boundary between Prince George's and Montgomery counties, was transferred to Montgomery County.[17] This was done after city residents voted to be under the sole jurisdiction of Montgomery County, and subsequent approval by both counties and the Maryland General Assembly. This was the first change in Prince George's County's boundaries since 1968, when the City of Laurel was unified in Prince George's County.

21st century

The county has a number of properties on the National Register of Historic Places.[18]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 499 square miles (1,290 km2), of which 483 square miles (1,250 km2) is land and 16 square miles (41 km2) (3.2%) is water.[19]

Prince George's County lies in the Atlantic coastal plain, and its landscape is characterized by gently rolling hills and valleys. Along its western border with Montgomery County, Adelphi, Calverton and West Laurel rise into the piedmont, exceeding 300 feet (91 m) in elevation.

The Patuxent River forms the county's eastern border with Howard, Anne Arundel, Charles and Calvert counties.

Regions

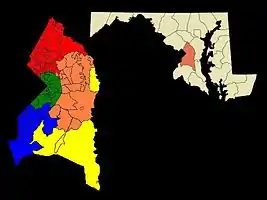

= North County

= Central County

= Rural Tier

= Inner Beltway

= South County

Terrain, culture, and demographics differ significantly by location within the county. There are five key regions to Prince George's County: North County, Central County, the Rural Tier, the Inner Beltway, and South County. These regions are not formally defined, however, and the terms used to describe each area can vary greatly.[20] In the broadest terms, the county is generally divided into North County and South County with U.S. Route 50 serving as the dividing line.[21]

North County

Northern Prince George's County includes Laurel, Beltsville, Adelphi, College Park and Greenbelt. This area of the county is anchored by the Capital Beltway and the Baltimore–Washington Parkway. Laurel is experiencing a population boom with the construction of the Inter-County Connector. The key employers in this region are the University of Maryland, Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, and NASA-Goddard Space Flight Center. Areas of geographic distinction include Greenbelt Park, a wooded reserve adjacent to the planned environmental community of Greenbelt, and University Park, a collection of historic homes adjacent to the University of Maryland. Riversdale Mansion, along with the historic homes of Berwyn Heights, Mt. Rainier and Hyattsville, along with Langley Park are also located in this area. The hidden Lake Artemesia, a park constructed during the completion of the Washington Metro Green Line, incorporates a stocked fishing lake and serves as the trail-head for an extensive Anacostia Tributary Trails system that runs along the Anacostia River and its tributaries. The south and central tracts of the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center also lie in this part of the county; the north tract lies north of the Patuxent River in Anne Arundel County.

Central County

Central County, located on the eastern outskirts of the Capital Beltway, consists of Mitchellville, Woodmore, Greater Upper Marlboro, Springdale, Largo, and Bowie. According to the 2010 census, it has generally been the fastest growing region of the county.[22] Mitchellville is named for a wealthy African American family, the Mitchells, who owned a large portion of land in this area of the county.[23] Central Avenue, a major exit off the I-95 beltway, running east to west, is one of two main roads in this portion of the county. The other major roadway is Old Crain Highway, which runs north to south along the eastern portion of the county. The Newton White Mansion on the grounds is a popular site for weddings and political events. Bowie State University and Prince George's Community College are in the Central region.

Bowie is best known as a planned Levittown.[24] William Levitt in the 1960s built traditional homes, as well as California contemporaries along U.S. Route 50, the key highway to the eastern shore and the state capital of Annapolis. Bowie has currently grown to be the largest city in Prince George's County, with more than 50,000 people. It also has a large Caucasian population, compared to much of the county (48% of the population).[25] Housing styles vary from the most contemporary to century old homes in Bowie's antique district (formerly known as Huntingtown), where the town of Bowie began as a haven for thoroughbred horse racing. Areas of geographic distinction include the Oden Bowie Mansion, Allen Pond, key segments of the Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Trail, as well as planned parks, lakes and walking trails.

Rural Tier

Prince George's rural tier was designated "in the 2002 General Plan as an area where residential growth would be minimal";[26] it may be found in the area well beyond the Beltway to the east and south of central county, bounded on the north by U.S. Route 50, the west by the communities Accokeek and Fort Washington, and the east by the Patuxent River. Prince George's origins are in this part of the county. Most of this area contains the unincorporated parishes, villages and lost towns of Prince George's County. Largely under postal designations of "Upper Marlboro" or "Brandywine", in truth the town of Upper Marlboro is more central county in character, though it is the post office location for various rural settlements. (The names of these unincorporated areas are listed below in the towns section of this article). Since 1721 Upper Marlboro has been the county seat of government, with families that trace their lineage back to Prince George's initial land grants and earliest governing officials. Names like Clagett, Sasscer, King James and Queen Anne pepper the streets.

The rural tier has been the focus of orchestrated efforts by residents and county government to preserve its rural character and environmental integrity.[27] Under the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC), Patuxent River Park is the largest natural preserve and provides public access for birdwatching and viewing the rural tier's natural waterfront vistas. In season, the park's Jug Bay Natural Area and the Patuxent Riverkeeper in Queen Anne both offer canoeing and kayaking rentals on the Patuxent. The county's largest collection of tobacco planter mansions and preserved homes are in the rural tier, some managed by the M-NCPPC. Many rural tier roads have scenic highway preservation status; a fall drive yields exceptional beauty along the Patuxent valley's Leeland Road, Croom Road, Clagett's Landing Rd., Mill Branch Rd., Queen Anne Rd., and Brandywine Rd. Walking access along roads in this area is very limited, because most property along the roads remains in private ownership. However, walking is much more accessible in the widespread M-NCPPC lands and trails and state holdings in the Patuxent valley, such as Merkle Wildlife Sanctuary and Rosaryville State Park, both popular among hikers and mountain bikers.

Inner Beltway

The inner beltway communities of Capitol Heights, District Heights, Forestville, Suitland, and Seat Pleasant border the neighboring District of Columbia's northeastern and southeastern quadrants. A high percentage of the residents of these communities are African-American.[28]

South County

South County is a blend of the greenery of the rural tier and the new development of central county. The communities of Clinton, Oxon Hill, Temple Hills and Fort Washington are the largest areas of south county. It is the only portion of Prince George's County to enjoy the Potomac River waterfront, and that geographic distinction has yielded the rise of the National Harbor project: a town center and riverside shopping and living development on the Potomac. The National Harbor, and its associated entertainment (MGM Resort and Casino) and shopping (Tanger Outlets) districts, have become a major tourist and convention attraction, with significant hotel accommodations, eateries and shopping. Together, these projects were built on land formerly occupied by the infamous "Salubria" plantation, where a 14-year-old slave girl poisoned her master and his family in 1831.[29] Water taxi service connects National Harbor to other destinations along the Potomac.[30] Several historic sites, including Jones Point Lighthouse, can be viewed from the harbor front. Piscataway Park in Accokeek preserves many acres of woodland and wetlands along the Potomac River opposite Mount Vernon, Virginia. River Road in Fort Washington also yields great views of the Potomac. Fort Washington Park was a major battery and gives access to the public for tours of the fort, scenic access to the river and other picnic grounds. Oxon Hill Manor offers a working farm and plantation mansion for touring; His Lordship's Kindness is another major historic home. Also, Fort Foote is an old American Civil War fort and tourist destination.

Adjacent counties and independent cities

- Anne Arundel County (east)

- Calvert County (southeast)

- Charles County (south)

- Howard County (north)

- Montgomery County (northwest)

- Fairfax County, Virginia (southwest)

- Alexandria, Virginia (southwest)

- Washington, D.C. (west)

Prince George's and Montgomery Counties share a bi-county planning and parks agency in the M-NCPPC and a public bi-county water and sewer utility in the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission

National protected areas

Politics and government

Since 1792, the county seat has been Upper Marlboro. Prior to 1792, the county seat was located at Mount Calvert, a 76-acre (308,000 m2) estate along the Patuxent River on the edge of what is now in the unincorporated community of Croom. Since 1991, the county has slowly moved government functions from rural Upper Marlboro to the Largo area, closer to the center of population, while proposals to move the actual county seat remain controversial.[31]

Prince George's County was granted a charter form of government in 1970 with the county executive elected as the head of the executive branch and the county council members as the leadership of the legislative branch. The county is divided into nine councilmanic districts, whose number designations wind roughly from north to south.[32] Two at-large council seats were added in 2018.[33] Prince George's County is part of the Seventh Judicial Circuit of the state of Maryland and holds 23 of the 32 total circuit court judges in the circuit (which includes Calvert, Charles, Prince George's, and St. Mary's counties).[34]

Fitch Ratings assigned a 'AAA' bond rating to Prince George's County on August 25, 2011, re-affirming the county's stable financial outlook. Earlier in 2011, the county received 'AAA' status from Standard & Poor's and Moody's. 'AAA' bond ratings are the highest possible bond ratings a jurisdiction can receive.[35]

As part of the increasingly liberal D.C. suburbs and a nationwide suburban shift towards the Democrats,[36] Prince George's County is a Democratic stronghold, having voted majority-Democratic in every presidential election but four since 1932: Dwight D. Eisenhower's landslide elections in 1952 and 1956, and Richard Nixon's two candidacies in 1968 and 1972.[37] It has not even given over 10% of the vote to the Republican nominee since 2008,[38] and was Joe Biden's strongest county in the country (and second-best county equivalent after Washington, D.C.) in the 2020 presidential election, awarding him 89.26% of the vote.[39]

| Voter registration and party enrollment of Prince George's County[40] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total | Percentage | |

| Democratic | 468,783 | 78.47% | |

| Republican | 39,314 | 6.58% | |

| Independents, unaffiliated, and other | 89,289 | 14.95% | |

| Total | 597,386 | 100.00% | |

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 8.7% 37,090 | 89.2% 379,208 | 2.0% 8,557 |

| 2016 | 8.4% 32,811 | 88.1% 344,049 | 3.5% 13,525 |

| 2012 | 9.2% 35,734 | 89.7% 347,938 | 1.1% 4,072 |

| 2008 | 10.4% 38,833 | 88.9% 332,396 | 0.8% 2,797 |

| 2004 | 17.4% 55,532 | 81.8% 260,532 | 0.8% 2,410 |

| 2000 | 18.4% 49,987 | 79.5% 216,119 | 2.1% 5,803 |

| 1996 | 21.9% 52,697 | 73.5% 176,612 | 4.6% 10,993 |

| 1992 | 24.5% 62,955 | 65.7% 168,691 | 9.8% 25,213 |

| 1988 | 38.8% 86,545 | 60.0% 133,816 | 1.1% 2,520 |

| 1984 | 41.0% 95,121 | 58.6% 136,063 | 0.5% 1,036 |

| 1980 | 40.7% 78,977 | 50.9% 98,757 | 8.4% 16,253 |

| 1976 | 42.0% 81,027 | 58.0% 111,743 | |

| 1972 | 58.6% 116,166 | 40.3% 79,914 | 1.2% 2,330 |

| 1968 | 41.2% 73,269 | 40.3% 71,524 | 18.5% 32,867 |

| 1964 | 36.2% 46,413 | 63.8% 81,806 | |

| 1960 | 42.0% 44,817 | 58.1% 62,013 | |

| 1956 | 50.9% 40,654 | 49.1% 39,280 | |

| 1952 | 56.3% 38,060 | 43.1% 29,119 | 0.6% 423 |

| 1948 | 49.0% 14,718 | 49.5% 14,874 | 1.4% 432 |

| 1944 | 49.5% 13,750 | 50.5% 14,006 | |

| 1940 | 36.3% 9,523 | 63.2% 16,592 | 0.5% 136 |

| 1936 | 34.8% 8,107 | 64.8% 15,087 | 0.4% 101 |

| 1932 | 36.1% 6,696 | 62.4% 11,580 | 1.5% 280 |

| 1928 | 59.1% 9,782 | 40.2% 6,658 | 0.7% 122 |

| 1924 | 47.0% 5,868 | 40.7% 5,088 | 12.3% 1,534 |

| 1920 | 56.8% 6,628 | 41.6% 4,857 | 1.5% 178 |

| 1916 | 45.4% 3,058 | 51.9% 3,493 | 2.7% 183 |

| 1912 | 27.3% 1,456 | 45.4% 2,424 | 27.4% 1,461 |

| 1908 | 48.9% 2,639 | 49.7% 2,680 | 1.5% 78 |

| 1904 | 55.4% 2,845 | 44.2% 2,270 | 0.5% 24 |

| 1900 | 55.0% 3,455 | 44.4% 2,787 | 0.6% 37 |

| 1896 | 55.9% 3,250 | 43.1% 2,505 | 0.9% 55 |

| 1892 | 47.3% 2,423 | 51.8% 2,655 | 0.8% 43 |

County executive and council

| Name | Party | Term |

|---|---|---|

| William W. Gullett | Republican | 1970–1974 |

| Win Kelly | Democratic | 1974–1978 |

| Lawrence Hogan | Republican | 1978–1982 |

| Parris N. Glendening | Democratic | 1982–1994 |

| Wayne K. Curry | Democratic | 1994–2002 |

| Jack B. Johnson | Democratic | 2002–2010 |

| Rushern L. Baker III | Democratic | 2010–2018 |

| Angela D. Alsobrooks | Democratic | 2018–date |

| Name | Party | District |

|---|---|---|

| Tom Dernoga | Democratic | 1 |

| Deni Taveras | Democratic | 2 |

| Dannielle Glaros | Democratic | 3 |

| Todd M. Turner (chair) | Democratic | 4 |

| Jolene Ivey | Democratic | 5 |

| Derrick Leon Davis | Democratic | 6 |

| Rodney Colvin Streeter (vice-chair) | Democratic | 7 |

| Monique Anderson-Walker | Democratic | 8 |

| Sydney Harrison | Democratic | 9 |

| Mel Franklin | Democratic | At-large |

| Calvin Hawkins | Democratic | At-large |

Other officials

- State's Attorney: Aisha N. Braveboy (D)[42]

- County Sheriff: Melvin C. High (D)[42]

- County Fire Chief: Tiffany D. Green

- Clerk of the Circuit Court: Mahasin El Amin[42]

- Chief of the County Police: Henry P. Stawinski III[43]

- PGCPS Chief Executive Officer: Monica Goldson[44]

Law enforcement

Prince George's County is serviced by multiple law enforcement agencies. The Prince George's County Police Department is the primary police service for county residents residing in unincorporated areas of the county. In addition, the Prince George's County Sheriff's Office acts as the enforcement arm of the county court, and also shares some patrol responsibility with the county police. County parks are serviced by the Prince George's County Division of the Maryland-National Capital Park Police. Besides the county-level services, all but one of the 27 local municipalities maintain police departments that share jurisdiction with the county police services. Furthermore, the Maryland State Police enforces the law on state highways which pass through the county with the exception of Maryland Route 200 where the Maryland Transportation Authority Police is the primary law enforcement agency and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources Police patrol the state parks and navigable waterways located within the county.

Along with the state and local law enforcement agencies, the federal government also maintains several departments that service citizens of the county such as the US Park Police, US Postal Police, Andrews Air Force Base Security Police, and other federal police located on various federal property within the county.

In addition, nearly all of the incorporated cities and towns in the county have their own municipal police force. Notable exceptions include the city of College Park.

Other emergency services

Prince George's County hospitals include Bowie Health Center, Doctors Community Hospital in Lanham, Gladys Spellman Specialty Hospital & Nursing Center in Cheverly, Laurel Regional Hospital in Laurel, Prince George's Hospital Center in Cheverly, Southern Maryland Hospital Center in Clinton, and Fort Washington Medical Center. Hospice of the Chesapeake has offices in Largo, with a staff that serves patients in their homes, including skilled nursing, senior living and assisted living facilities.

The Prince George's County Volunteer Firemen's Association was formed in 1922 with several of the first companies organized in the county. The first members of the association were Hyattsville, Cottage City, Mount Rainier, and Brentwood.

In March 1966, the Prince George's County Government employed the firefighters who had been hired by individual volunteer stations and an organized career department was begun. The career firefighters and paramedics are represented by IAFF 1619. Prince George's County Fire/Rescue Operations consists of 45 Fire/EMS stations.[45]

Prince George's County became the first jurisdiction in Maryland to implement the 9-1-1 Emergency Reporting System in 1973. Advanced life support services began for citizens of the county in 1977. Firefighters were certified as Cardiac Rescue Technicians and deployed in what was called at the time Mobile Intensive Care Units to fire stations in Brentwood, Silver Hill, and Laurel.

As of 2007, the Prince George's County Fire/EMS Department operates a combination system staffed by over 800 career firefighters and paramedics, and nearly 1,100 active volunteers.

Transportation

The County contains a 28-mile portion of the 65-mile-long Capital Beltway. After a decades-long debate, an east–west toll freeway, the Intercounty Connector ("ICC"), which extends Interstate 370 in Montgomery County to connect I-270 with Interstate 95 and U.S. 1 in Laurel, opened in 2012. An 11.5-mile portion of the 32.5-mile-long Baltimore–Washington Parkway runs from the county's border with Washington, D.C., to its border with Anne Arundel County near Laurel.

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority operates Metrobus fixed-route bus service and Metrorail heavy-rail passenger service in and out of the county as well as the regional MetroAccess paratransit system for the handicapped. The Prince George's County Department of Public Works and Transportation also operates TheBus, a County-wide fixed-route bus system, and the Call-A-Bus service for passengers who do not have access to or have difficulty using fixed-route bus service. Call-A-Bus is a demand-response service which generally requires 14-days advance reservations. The county also offers a subsidized taxicab service for elderly and disabled residents called Call-A-Cab in which eligible customers who sign up for the service purchase coupons giving them a 50 percent discount with participating taxicab companies in Prince George's and Montgomery Counties.

Prince George's County Metro Rail

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority has fifteen stations of the Washington Metro system located in Prince George's County, with four of them as terminus stations: Greenbelt, New Carrollton, Largo, and Branch Avenue. The Purple Line, which would link highly developed areas of both Montgomery and Prince George's Counties is currently under-construction and slated to open in 2022. The Purple Line will provide connections to the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority's Red Line (Washington Metro) via Northern Prince George's County and Montgomery County. The Orange Line (Washington Metro) and MARC Train's Penn Line will have transfer points at New Carrollton station.

Prince George's County Commuter Rail

The MARC Train (Maryland Area Rail Commuter) train service has two lines that traverse Prince George's County. The Camden Line, which runs between Baltimore Camden Station and Washington Union Station and has six stops in the county at Riverdale, College Park, Greenbelt, Muirkirk, Laurel and Laurel Race Track. The Penn Line runs on the Amtrak route between Pennsylvania and Washington Union stations. It has three stops in the county: Bowie, Seabrook and New Carrollton.

Airports

The College Park Airport (CGS), established in 1909, is the world's oldest continuously operated airport and is home to the adjacent College Park Aviation Museum.

Privately owned general aviation airfields in the county include Freeway Airport (W00) in Mitchellville, Potomac Airfield (VKX) in Friendly, and Washington Executive Airpark/Hyde Field (W32) in Clinton, along with numerous private heliports.[46]

The area is served by three airports: Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) in Arlington County, Virginia, Baltimore–Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI) in neighboring Anne Arundel County, and Dulles International Airport (IAD) in Dulles, Virginia.

Andrews Air Force Base (ADW), the airfield portion of Joint Base Andrews, is also near Camp Springs.

Water taxi

Prince George's County is served by a water taxi that operates form the National Harbor to Alexandria, Virginia and to The Wharf in Washington, D.C.[47]

Major highways

Future transit

Because of its location north and east of Washington, D.C., several future transit technology projects look to be routed partially through Prince George's County. The first stage of The Boring Company's proposed Washington-to-New York hyperloop will travel beneath the Baltimore–Washington Parkway through Prince George's en route to Baltimore.[48][49] No hyperloop stops within the county are projected. Similarly, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan has supported efforts to trial a 40-mile superconducting maglev (SCMaglev) train route connecting Washington to Baltimore. Proposed routes would run through Prince George's parallel to the Baltimore–Washington Parkway or along the Amtrak Penn Line corridor.[50] As with the hyperloop, no SCMaglev stop is planned within Prince George's County. The Purple Line light transit rail is currently in construction in College Park and New Carrollton.[51]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 21,344 | — | |

| 1800 | 21,175 | −0.8% | |

| 1810 | 20,589 | −2.8% | |

| 1820 | 20,216 | −1.8% | |

| 1830 | 20,474 | 1.3% | |

| 1840 | 19,539 | −4.6% | |

| 1850 | 21,549 | 10.3% | |

| 1860 | 23,327 | 8.3% | |

| 1870 | 21,138 | −9.4% | |

| 1880 | 26,451 | 25.1% | |

| 1890 | 26,080 | −1.4% | |

| 1900 | 29,898 | 14.6% | |

| 1910 | 36,147 | 20.9% | |

| 1920 | 43,347 | 19.9% | |

| 1930 | 60,095 | 38.6% | |

| 1940 | 89,490 | 48.9% | |

| 1950 | 194,182 | 117.0% | |

| 1960 | 357,395 | 84.1% | |

| 1970 | 660,567 | 84.8% | |

| 1980 | 665,071 | 0.7% | |

| 1990 | 729,268 | 9.7% | |

| 2000 | 801,515 | 9.9% | |

| 2010 | 863,420 | 7.7% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 909,327 | [52] | 5.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[53] 1790–1960[54] 1900-1990[55] 1990-2000[56] 2010–2018[5] | |||

Prince George's County is the wealthiest African American-majority county in the United States.[57][58]

2000

The racial makeup of the county was as of 2000:

- 62.70% Black

- 27.04% White

- 0.35% Native American

- 7.12% Hispanic or Latino (of any race)

- 3.87% Asian

- 0.06% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- 3.38% Some other race

- 2.61% Two or more races

By the 2008 estimates there were 298,439 households, out of which 65.1% are family households and 34.9% were non-family households. 36.4% of households had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.00% were married couples living together, 19.60% had a female householder with no husband present. 24.10% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.74 persons and the average family size was 3.25 persons.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 26.80% under the age of 18, 10.40% from 18 to 24, 33.00% from 25 to 44, 22.10% from 45 to 64, and 7.70% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.20 males.

The median income for a household in the county in 2008 was $71,696,[5] and the median income for a family was $81,908. The 2008 mean income for a family in the county was $94,360. As of 2000, males had a median income of $38,904 versus $35,718 for females. The 2008 per capita income for the county was $23,360. About 4.70% of families and 7.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.2% of those under age 18 and 7.1% of those age 65 or over. Prince George's County is the 70th most affluent county in the United States by median income for families and the most affluent county in the United States with an African-American majority. Almost 38.8% of all households in Prince George's County, earned over $100,000 in 2008.[59]

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 863,420 people, 304,042 households, and 203,520 families residing in the county.[60] The population density was 1,788.8 inhabitants per square mile (690.7/km2). There were 328,182 housing units at an average density of 679.9 per square mile (262.5/km2).[61] The racial makeup of the county was 64.5% black or African American, 19.2% White (14.9% non-Hispanic White), 4.1% Asian, 0.5% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 8.5% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 14.9% of the population.[60] In terms of ancestry, 6.5% were Subsaharan African, and 2.0% were American.[62]

Of the 304,042 households, 36.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.1% were married couples living together, 20.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 33.1% were non-families, and 26.1% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.78 and the average family size was 3.31. The median age was 34.9 years.[60]

The median income for a household in the county was $71,260 and the median income for a family was $82,580. Males had a median income of $49,471 versus $49,478 for females. The per capita income for the county was $31,215. About 5.0% of families and 7.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.6% of those under age 18 and 6.7% of those age 65 or over.[63]

Education

"30.1% of all residents over the age of 25 had graduated from college and obtained a bachelor's degree (17.8%) or professional degree (12.2%). 86.2% of all residents over the age of 25 were high school graduates or higher."[64]

Religion

Prince George's County is home to more than 800 churches, including 12 megachurches,[65] as well as a number of mosques, synagogues, and Hindu and Buddhist temples. Property belonging to religious entities makes up 3,450 acres (14.0 km2) of land in the county, or 1.8% of the total area of the county.[66]

Economy

Top employers

According to the county's comprehensive annual financial report, the top private-sector employers in the county are the following. "NA" indicates not in the top ten for the year given.

| Employer | Employees (2014)[67] |

Employees (2011)[68] |

Employees (2005)[68] |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Parcel Service (UPS) | 4,220 | 4,220 | 2,300 |

| Giant | 3,000 | 3,600 | 6,152 |

| Verizon | 2,738 | 2,738 | NA |

| Dimensions Healthcare System | 2,500 | 2,500 | 2,100 |

| Marriott International (Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center) |

2,430 | 2,000 | NA |

| Shoppers Food & Pharmacy | 1,975 | 1,975 | 1,975 |

| Safeway | 1,605 | 1,605 | 2,400 |

| Capital One Bank (formerly Chevy Chase Bank) | NA | 1,456 | NA |

| Target | 1,400 | 1,400 | NA |

| Doctor's Community Hospital | 1,300 | 1,300 | NA |

| MedStar Health (Southern Maryland Hospital Center) |

1,242 | 1,300 | 1,300 |

The top public-sector employers in the county are:

| Employer | Employees (2014)[67] |

Employees (2011)[68] |

|---|---|---|

| University System of Maryland | 17,905 | 16,014 |

| Joint Base Andrews Naval Air Facility Washington | 13,500 | 8,057 |

| Prince George's County | 7,003 | 7,052 |

| Internal Revenue Service | 5,539 | 5,539 |

| U.S. Census Bureau | 4,414 | 4,287 |

| NASA Goddard Space Flight Center | 3,397 | 3,171 |

| Prince George's Community College | 2,637 | 1,700 |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture (Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center) |

1,850 | 1,850 |

| National Maritime Intelligence-Integration Office | 1,724 | 1,724 |

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | 1,350 | 1,350 |

Crime

Prince George's County accounted for 20% of murders in the State of Maryland from 1985 to 2006.[69] A twenty-year crime index trends study, performed by Prince George's County Police Department Information Resource Management, showed the county had a 23.1% increase in total crime for the years of 2000 to 2004. Between the years of 1984 to 2004, Prince George's had a 62.8% increase in total crime.[70]

However, as of 2009, crime had generally declined in the county[71] and the number of homicides declined from 151 in 2005 to 99 in 2009.[72][73]

As of the end of 2013, the county had experienced a record drop in crime, especially record lows in violent crimes.[74]

Education

Colleges and universities

- Bowie State University, located in unincorporated area north of Bowie

- Brightwood College, located in unincorporated area (Beltsville)

- Capital Seminary & Graduate School, in Greenbelt

- Capitol Technology University, located in unincorporated area south of Laurel

- Prince George's Community College, located in unincorporated area (Largo)

- Strayer University, PG Campus, in unincorporated area (Suitland)

- University of Maryland, College Park, in College Park

- University of Maryland Global Campus, in unincorporated area (Adelphi)

The University of Maryland System headquarters are in the unincorporated area of Adelphi.[75]

Public schools

The county's public schools are managed by the Prince George's County Public Schools system.

Enterprises and recreation

Prince George's County is home to the United States Department of Agriculture's Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the United States Census Bureau, Andrews Air Force Base, the National Archives and Records Administration's College Park facility, the University of Maryland’s flagship College Park campus, Six Flags America and Six Flags Hurricane Harbor, FedExField (home of the Washington Football Team), and the National Harbor, which its developers, Peterson Companies and Gaylord Entertainment Company, bill as the largest single mixed-use project and combined convention center–hotel complex on the East Coast.

Media

Recreation

Although Prince George's County is not often credited for the Washington Football Team, the team's home stadium, FedExField, is in Landover. No other major-league professional sports teams are in the county, though Bowie hosts the Bowie Baysox, a minor league baseball team. The county is known for its very successful youth. In basketball, ESPN published an article declaring Prince George's County the new "Hoops Hot Bed" and ranked it as the number one basketball talent pool in the country.[77] A number of basketball prospects, including Kevin Durant, Victor Oladipo, Jeff Green, Roy Hibbert and Ty Lawson, are from AAU basketball teams such as the PG Jaguars, DC Assault, and DC Blue Devils. Besides AAU, basketball has skyrocketed from local high schools such as DeMatha Catholic High School and Bishop McNamara High School, both of which have found some great success locally and nationally.

The county's basketball talent was profiled in the 2020 documentary Basketball County, produced by Kevin Durant. Durant and numerous other residents of the county who went on to success in basketball are featured in the film.[78]

Communities

This county contains the following incorporated municipalities:

Cities

Towns

Part of the city of Takoma Park was formerly in Prince George's County, but since 1997 the city has been entirely in Montgomery County.[79] The part of Takoma Park that changed counties comprises two residential neighborhoods, Carole Highlands (an unincorporated portion of which is still in Prince George's County) and New Hampshire Gardens.

Census-designated places

Unincorporated areas are also considered as towns by many people and listed in many collections of towns, but they lack local government. Various organizations, such as the United States Census Bureau, the United States Postal Service, and local chambers of commerce, define the communities they wish to recognize differently, and since they are not incorporated, their boundaries have no official status outside the organizations in question. The Census Bureau recognizes the following census-designated places in the county:

- Accokeek

- Adelphi

- Andrews AFB

- Aquasco

- Baden

- Beltsville

- Brandywine

- Brock Hall

- Calverton

- Camp Springs

- Cedarville

- Chillum

- Clinton

- Coral Hills

- Croom

- East Riverdale

- Fairwood

- Forestville

- Fort Washington

- Friendly

- Glassmanor

- Glenn Dale

- Hillandale

- Hillcrest Heights

- Kettering

- Konterra

- Lake Arbor

- Landover

- Langley Park

- Lanham

- Largo

- Marlboro Meadows

- Marlboro Village

- Marlow Heights

- Marlton

- Melwood

- Mitchellville

- National Harbor

- Oxon Hill

- Peppermill Village

- Queen Anne

- Queenland

- Rosaryville

- Seabrook

- Silver Hill

- South Laurel

- Springdale

- Suitland

- Summerfield

- Temple Hills

- Walker Mill

- West Laurel

- Westphalia

- Woodlawn

- Woodmore

Unincorporated communities

- Ardmore

- Avondale

- Berwyn

- Carmody Hills

- Carole Highlands

- Cedar Heights

- Chapel Oaks

- Cheltenham

- Collington

- Danville

- Green Meadows

- Indian Creek Village

- Kentland

- Lewisdale

- Meadows

- Montpelier

- Muirkirk

- North College Park

- Palmer Park

- Piscataway

- Raljon

- Rogers Heights

- South Bowie

- Tantallon

- Tuxedo

- Vansville

- West Hyattsville

- White Hall

- Woodyard

Ghost town

Sister cities

Prince George's County has three sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Royal Bafokeng Nation, South Africa

Royal Bafokeng Nation, South Africa Rishon LeZion, Israel

Rishon LeZion, Israel Ziguinchor, Senegal

Ziguinchor, Senegal

Notable people

- Karen Allen, actor, (National Lampoon's Animal House, Raiders of the Lost Ark), director, grew up in New Carrollton and attended DuVal High School.

- Thurl Bailey, professional basketball player; grew up in Landover.[80]

- Ben Barnes, Member of the Maryland House of Delegates, from Greenbelt, Maryland.

- John H. Bayne, 19th-century founder of the University of Maryland, superintendent of county schools, Union Army physician, and one of the first Americans to grow and eat a tomato, proving they were not poisonous as had been thought, lived on Oxon Hill Road in Oxon Hill.[81]

- Michael Beasley, professional basketball player for the New York Knicks

- Len Bias, All-American Basketball star at the University of Maryland in the 1980s, grew up in Landover Hills and attended Northwestern High School in Hyattsville.

- Riddick Bowe, former world heavyweight boxing champion, and family lived in Sero Estates, Fort Washington.

- Sergey Brin, founder of Google, grew up in Adelphi and attended Eleanor Roosevelt High School in Greenbelt.

- Steve Byrnes, Former NASCAR TV analyst, grew up in New Carrollton, attended both Largo High School & University of Maryland

- John Carroll, S.J. (1735–1815), first Roman Catholic bishop and archbishop in the United States, and founder of Georgetown University, was born in Upper Marlboro.

- Eva Cassidy, songstress and guitarist, grew up in Oxon Hill and later Bowie.

- JC Chasez, singer/producer, grew up in Bowie.

- Frank Cho, award-winning cartoonist, grew up in Beltsville and attended community college and university in the county.

- Thomas John Claggett (1742–1816), first Episcopal bishop consecrated in the United States and third Chaplain of the United States Senate, was from Upper Marlboro.

- Leonard Covington (1768–1813), born in Aquasco, U.S. congressman from Maryland[82]

- Jermaine Crawford, actor, The Wire, born and raised in the county

- Kevin Durant, NBA player, grew up in Prince George's County

- Roger Easton, Sr., naval scientist, the chief inventor of GPS and winner of the 2004 National Medal of Technology, lived on Oxon Hill Road in Oxon Hill.

- Francis B. Francois, lawyer and engineer, lived in Bowie for over 40 years. In 1999, he was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in recognition of his achievements in the field of engineering and policy leadership in surface transportation infrastructure and research. He served on the Prince George's County council as an elected official for 10 years.

- Markelle Fultz, NBA player, born and raised in Upper Marlboro.

- Danny Gatton, extraordinary guitarist, lived in Oxon Hill and graduated from Oxon Hill Senior High School, later lived for many years in Accokeek.

- Steven F. Gaughan, Prince George's County police officer killed in the line of duty in 2005

- Kathie Lee Gifford, network television personality, grew up in Bowie.

- Ginuwine, R&B pop musician, lived in Fort Washington.

- Lyle Goodhue (1903–1981), USDA research scientist and inventor, lived in Prince George's County from 1935 to 1945.

- Jeff Green, NBA player for the Brooklyn Nets.

- Anthony Hampton (Television Producer and entrepreneur )

- Goldie Hawn, actress, director, and producer, grew up in Takoma Park before it was transferred to Montgomery County.

- Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets later used on Sesame Street, grew up in University Park and attended Northwestern High School in Hyattsville.

- Taraji P. Henson, actress, attended Oxon Hill High School.

- Roy Hibbert, professional basketball player for the Indiana Pacers, and raised in Adelphi

- Larry Hogan, the current and 62nd Governor of Maryland since 2015, grew up in Landover, attended Saint Abrose Catholic School in Cheverly and DeMatha Catholic High School in Hyattsville. As a result of his parents' divorce, Hogan moved to Florida and later moved back to Maryland to Anne Arundel County, where he currently resides.

- Steny Hoyer, Floor leader of the United States House of Representatives since 2003, lived as a teenager in Suitland and Mitchellville, attended Suitland High School and Univ. Maryland – College Park, and later lived in Friendly before moving to St. Mary's County.

- Cathy Hughes, founder and manager of Radio One, the nation's largest African American broadcasting company

- Jarrett Jack, a professional basketball player for the Brooklyn Nets.

- Isis King, first transgender contestant in America's Next Top Model (Cycles 11 and 17)

- Jeff Kinney, author of the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series, is from Fort Washington.

- Martin Lawrence, actor and comedian, lived in Landover and attended Eleanor Roosevelt High School in Greenbelt

- Ty Lawson NBA player for the Washington Wizards.

- Sugar Ray Leonard, boxing champion, grew up in Palmer Park.

- G. Gordon Liddy, presidential aide convicted in the Watergate scandal, later an author and radio personality, lives in Fort Foote, Fort Washington.

- John P. McDonough, Maryland Secretary of State, from Bladensburg.

- Mike Miller, Maryland State Senate President from 1987 to 2020, was born and raised in Clinton and attended Surrattsville High School. Miller studied Business Administration at the University of Maryland, College Park, graduating in 1964. Miller's law firm is located in Clinton. Miller currently resides in Calvert County.

- Mýa, R&B pop musician, attended Eleanor Roosevelt High School in Greenbelt, Maryland as a violinist in the orchestra among the class of 1994.

- Sammy Nestico, band music arranger, lived in Oxon Hill in the 1960s.

- Lio Rush, professional WWE wrestler from Lanham.

- Jan Scruggs, who conceived the National Vietnam Veterans Memorial, grew up in Bowie.

- Substantial, rapper originally from Cheverly.

- Michael Sweetney, a former professional basketball player.

- Turkey Tayac, Piscataway Indian leader and herbal doctor, lived in Accokeek for many years and is buried there.

- Dominic Wade, professional boxer, from Largo.

- Wale, a hip-hop artist, who often notes in his songs how he is from "PG County," and the "DMV" region (D.C, Maryland, Virginia).

- Sumner Welles, U.S. Undersecretary of State to Franklin Roosevelt, built and lived in Oxon Hill Manor, which is now a public facility.

- Delonte West, a former NBA player and graduate of Eleanor Roosevelt High School in Greenbelt, MD

- Morgan Wootten coached at DeMatha Catholic High School in Hyattsville from 1956 to 2002. The coach with the most wins in high school basketball history, he was elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame, the only high school basketball coach ever so honored. He currently resides in University Park.

- Link Wray, pioneering rock guitarist, lived in Accokeek for many years.

- Robert M. Wright, born in Prince George's County in 1840; one of the founders of Dodge City, Kansas

Namesakes

- The USS Prince Georges (AK-224), was a United States Navy Crater-class cargo ship named after the county.

References

- "Section 103. - Name and Boundaries". THE COUNTY CODE - PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY, MARYLAND. 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

The corporate name shall be 'Prince George's County, Maryland,' and it shall thus be designated in all actions and proceedings touching its rights, powers, properties, liabilities, and duties. Its boundaries and County seat shall be and remain as they are at the time this Charter takes effect unless otherwise changed in accordance with law.

- Parker, Lonnae O'Neal; Wiggins, Ovetta (May 7, 2006). "'P.G.': Insult or Abbreviation?". The Washington Post. p. C05. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- Hiaasen, Rob (May 12, 2000). "In the lingo of life, 'PG' fits right in". The Baltimore Sun. Maryland. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "History – Prince George's County, MD". www.princegeorgescountymd.gov.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 3, 2001. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Rowlands, D.W. (January 13, 2020). "How the region's racial and ethnic demographics have changed since 1970". D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- Brown, DeNeen L. (January 23, 2015). "Prince George's neighborhoods make 'Top 10 List of Richest Black Communities in America'". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- Prince George's County (April 3, 2000). "Subtitle 1: General Provisions". 103: Name and Boundaries. Title 17, the Public Local Laws of Prince George's County, Part II. Prince George's County, Maryland: Prince George's County. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

Section 103. Name and Boundaries. The corporate name shall be "Prince George's County, Maryland," and it shall thus be designated in all actions and proceedings touching its rights, powers, properties, liabilities, and duties. Its boundaries and County seat shall be and remain as they are at the time this Charter takes effect unless otherwise changed in accordance with law.

- "Dinosaur Park Officially Dedicated and Opened To the Public". pgparks.com. Prince George's County Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- Roylance, Frank D. (October 29, 2009). "Where dinosaurs once walked". baltimoresun.com. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- Walker, Childs (January 16, 2012). "Md. recognition of Piscataways adds happy note to complicated history". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- "Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 1696/7:1698, Volume 23, Page 23". Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- "Fight to Freedom: Slavery and the Underground Railroad in Maryland from the Maryland State Archives". Archived from the original on August 20, 2004.

- Records & Recollections – Early Black History in Prince George's County, Maryland by Bianca P. Floyd, M-NCPPC ©1989

- PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY HITTING 300 Washington Post – Friday, April 19, 1996 Author: Larry Fox

- "Substantial Changes to Counties and County Equivalent Entities: 1970–Present". Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- Rowlands, D.W. (May 8, 2018). "What do you call different regions of Prince George's County? Even for locals, it's complicated". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- Rowlands, D.W. (May 25, 2018). "We asked, you answered: here are our readers' names for regions of Prince George's County". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- Bloch, Matthew; Carter, Shan; McLean, Alan (December 13, 2010). "Mapping the 2010 U.S. Census". New York Times. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Michael F., Dwyer (1974). "Maryland Historic Trust Inventory Form For State Historic Sites Survey PG:71B-8". Silver Spring, Maryland: Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission: 3. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Baltz, Shirley Vlasak (1984). A Chronicle of Belair. Bowie, Maryland: Bowie Heritage Committee. pp. 84–88. LCCN 85165028.

- "Bowie city, Maryland – Fact Sheet – American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Submittal to the Maryland Department of Planning Regarding Conformance with SB 236" (PDF). Prince George's County, Maryland. January 22, 2013. p. 7. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- "Prince George's County Planning". Coalition for Smart Growth. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- Downs, Kat; Keating, Dan; Vaughn Kelso, Nathaniel. "Segregation Receding". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Muhammad, Askia (February 3, 2012). "Plantation where 14-year-old slave was hung to become outlet mall". TheFinalCall. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- Calbaugh, Jeff (March 1, 2018). "The Wharf water taxi service to National Harbor starts". WTOP. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- Hernández, Arelis R. (July 22, 2015). "Baker wants to move government headquarters to Largo, lawmakers say" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- "Councilmanic Districts". Prince Georg's Countu Council. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Cook, Gina (November 6, 2018). "Prince George's Elects Dems to At-Large Council; Alsobrooks Elected County Exec". NBC4 Washington. Archived from the original on November 13, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- "Maryland Circuit Courts – Origin & Functions". Msa.md.gov. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Fitch Assigns 'AAA' Bond Rating to Prince George's County". Prince George's County, Maryland Homepage. August 26, 2011. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- Tavernise, Sabrina; Gebeloff, Robert; Leatherby, Lauren (November 9, 2019). "How Voters Turned Virginia From Deep Red to Solid Blue (Published 2019)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Kestenbaum, Lawrence. "The Political Graveyard: Prince George's County, Md". The Political Graveyard. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- "United States Presidential Election Results". USElectionAtlas.org. David Leip. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- "2020 Preisdential Election Statistics". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- "Monthly Statistical Report". Prince George’s County Board of Elections. September 1, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- "United States Presidential Election Results". USElectionAtlas.org. David Leip. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- "Elected Officials". Prince George's County, Maryland. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- "A Message from the Chief". Prince George's County, Maryland. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "Chief Executive Officer". Prince George's County Public Schools. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "Fire / Rescue Operations". Prince George's County, Maryland. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- "Prince Georges County Public and Private Airports, Maryland". Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- "Potomac Riverboat Company Water Taxi". Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- Morris, David Z. (February 17, 2018). "Washington, D.C., Has Given the Boring Company a Permit for a Possible Hyperloop Station". Fortune. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- Goldchain, Michelle (March 26, 2018). "Elon Musk's D.C.–Baltimore hyperloop route, mapped". Curbed: Washington DC. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- Di Caro, Martin (October 19, 2017). "Maryland Eyes Three Possible Routes For High-Speed Maglev Between D.C. And Baltimore". WAMU-FM. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- "Construction Updates". Purple Line. Maryland Transit Administration. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- Howell, Tom Jr. (April 18, 2006). "Census 2000 Special Report. Maryland Newsline, Census: Md. Economy Supports Black-Owned Businesses". University of Maryland. Philip Merrill College of Journalism. Archived from the original on March 28, 2007.

- Chappell, Kevin (November 2006). "America's Wealthiest Black County". Ebony. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "Prince George's County, Maryland - Selected Economic Characteristics: 2006-2008". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006–2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "Prince George's County, Maryland: History and Information". www.ereferencedesk.com. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- The Partnership for Prince George's. "The Partnership for Prince George's About Us". Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Harris, Sudarsan; Harris, Hamil R. (March 14, 2005). "Tax Exempt and Growing, Churches Worry Pr. George's". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Year Ending June 30, 2014, Prince George's County, Maryland.

- "CAR 2011" (PDF). Prince George's County: Office of Finance of Prince George's County. June 2011. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 24, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- Virtually Everything, Inc. (April 24, 2007). "Baltimore, Prince George's Reign as State's Murder Capitals – Southern Maryland Headline News". Somd.com. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- Archived March 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Crime in Prince George's is at lowest level since 1975, police say". Gazette.net. January 14, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "december08ucr_county.xls" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "goprincegeorgescounty.com" (PDF). March 25, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2018.

- Bell, Brad (January 2, 2014). "Prince George's County violent crime drops for 3rd straight year". WJLA-TV. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- "Contact/Visit Us." University System of Maryland. Retrieved on September 18, 2012. "3300 Metzerott Road Adelphi, MD 20783" – See also Directions to USM Office

- "Prince George's Sentinel". Mondo Times. Mondo Code LLC.

- Palmer, Chris (December 17, 2008). "What's the hoops hotbed of the US right now? Chicago? No. LA? Nope. NYC? Sorry. Welcome to Prince George's County, MD". ESPN. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- Langmann, Brady (May 15, 2020). "A County in Maryland Produces a Wild Number of Basketball Stars. This Documentary Wants to Know Why". Esquire. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Montgomery, David (November 8, 1995). "In a Montgomery State of Mind, Takoma Park Votes to Unify". Washington Post.

- Johnson, Page (February 17, 2005). "Thurl Bailey: A Man as Big as His Vision of Life". Meridian Magazine.

- "Dr. John H. Bayne: A Leader In His Community". historicalmarkerproject.com. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

Further reading

- The Public Local Laws of Prince George's County. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015.

- The Dilemma of the Black Middle Class, includes analysis of the county.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prince George's County, Maryland. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Prince George's County. |

| Look up Prince George's County in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |