Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta

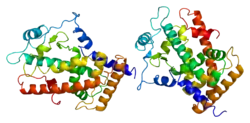

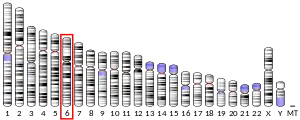

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta or delta (PPAR-β or PPAR-δ), also known as NR1C2 (nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group C, member 2) is a nuclear receptor that in humans is encoded by the PPARD gene.[5]

This gene encodes a member of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family. It was first identified in Xenopus in 1993.[6]

Function

PPARδ is a nuclear hormone receptor that governs a variety of biological processes and may be involved in the development of several chronic diseases, including diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, and cancer.[7][8]

In muscle PPAR-β/δ expression is increased by exercise, resulting in increased oxidative (fat-burning) capacity and an increase in type I fibers.[9] Both PPAR-β/δ and AMPK agonists are regarded as exercise mimetics.[10] In adipose tissue PPAR-β/δ increases both oxidation as well as uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation.[9]

PPARδ may function as an integrator of transcription repression and nuclear receptor signaling. It activates transcription of a variety of target genes by binding to specific DNA elements. Well described target genes of PPARδ include PDK4, ANGPTL4, PLIN2, and CD36. The expression of this gene is found to be elevated in colorectal cancer cells.[11] The elevated expression can be repressed by adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC), a tumor suppressor protein involved in the APC/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Knockout studies in mice suggested the role of this protein in myelination of the corpus callosum, epidermal cell proliferation, and glucose[12] and lipid metabolism.[13]

This protein has been shown to be involved in differentiation, lipid accumulation,[14] directional sensing, polarization, and migration in keratinocytes.[15]

Role in cancer

Studies into the role of PPARδ in cancer have produced contradictory results and there is no scientific consensus on whether it promotes or prevents cancer formation.[16][17] PPARδ favours tumour angiogenesis.[18]

Pharmacology

Several high affinity ligands for PPARδ have been developed, including GW501516 and GW0742, which play an important role in research. In one study utilizing such a ligand, it has been shown that agonism of PPARδ changes the body's fuel preference from glucose to lipids.[19]

Tissue distribution

PPARδ is highly expressed in many tissues, including colon, small intestine, liver and keratinocytes, as well as in heart, spleen, skeletal muscle, lung, brain and thymus.[20]

Knockout studies

Knockout mice lacking the ligand binding domain of PPARδ are viable. However, these mice are smaller than the wild type both neo and postnatally. In addition, fat stores in the gonads of the mutants are smaller. The mutants also display increased epidermal hyperplasia upon induction with TPA.[21]

Ligands

PPARδ is activated in the cell by various fatty acids and fatty acid derivatives.[7] Examples of naturally occurring fatty acids that bind with and activate PPAR delta include arachidonic acid and certain members of the 15-hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid family of arachidonic acid metabolites including 15(S)-HETE, 15(R)-HETE, and 15-HpETE.[22] Several synthetic ligands have been identified that selectively bind PPARδ.

Agonists

Interactions

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta has been shown to interact with HDAC3[24][25] and NCOR2.[25]

References

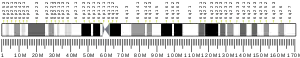

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000112033 - Ensembl, May 2017

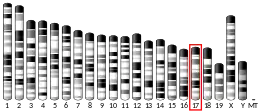

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000002250 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Schmidt A, Endo N, Rutledge SJ, Vogel R, Shinar D, Rodan GA (1992). "Identification of a new member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily that is activated by a peroxisome proliferator and fatty acids". Mol. Endocrinol. 6 (10): 1634–41. doi:10.1210/me.6.10.1634. PMID 1333051.

- Krey G, Keller H, Mahfoudi A, Medin J, Ozato K, Dreyer C, Wahli W (1993). "Xenopus peroxisome proliferator activated receptors: genomic organization, response element recognition, heterodimer formation with retinoid X receptor and activation by fatty acids". J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 47 (1–6): 65–73. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(93)90058-5. PMID 8274443. S2CID 25098754.

- Berger J, Moller DE (2002). "The mechanisms of action of PPARs". Annu. Rev. Med. 53: 409–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018. PMID 11818483.

- Feige JN, Gelman L, Michalik L, Desvergne B, Wahli W (2006). "From molecular action to physiological outputs: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear receptors at the crossroads of key cellular functions". Prog. Lipid Res. 45 (2): 120–59. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2005.12.002. PMID 16476485.

- Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, Embler E, Wang YX, Banayo E, Mihaylova MM, Nelson MC, Zou Y, Juguilon H, Kang H, Shaw RJ, Evans RM (2015). "Integrative and systemic approaches for evaluating PPARβ/δ (PPARD) function". Nuclear Receptor Signaling. 13: eoo1. doi:10.1621/nrs.13001. PMC 4419664. PMID 25945080.

- Giordano Attianese GM, Desvergne B (2008). "AMPK and PPARdelta agonists are exercise mimetics". Cell. 134 (3): 405–415. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.051. PMC 2706130. PMID 18674809.

- Takayama O, Yamamoto H, Damdinsuren B, Sugita Y, Ngan CY, Xu X, Tsujino T, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Matsuura N, Monden M (2006). "Expression of PPARδ in multistage carcinogenesis of the colorectum: implications of malignant cancer morphology". Br. J. Cancer. 95 (7): 889–95. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603343. PMC 2360534. PMID 16969348.

- Lee CH, Olson P, Hevener A, Mehl I, Chong LW, Olefsky JM, Gonzalez FJ, Ham J, Kang H, Peters JM, Evans RM (2006). "PPARδ regulates glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (9): 3444–9. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.3444L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0511253103. PMC 1413918. PMID 16492734.

- "Entrez Gene: PPARD peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta".

- Schmuth M, Haqq CM, Cairns WJ, Holder JC, Dorsam S, Chang S, Lau P, Fowler AJ, Chuang G, Moser AH, Brown BE, Mao-Qiang M, Uchida Y, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J, Chambon P, Willson TM, Elias PM, Feingold KR (April 2004). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-beta/delta stimulates differentiation and lipid accumulation in keratinocytes". J. Invest. Dermatol. 122 (4): 971–83. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22412.x. PMID 15102088.

- Tan NS, Icre G, Montagner A, Bordier-ten-Heggeler B, Wahli W, Michalik L (October 2007). "The Nuclear Hormone Receptor Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor β/δ Potentiates Cell Chemotactism, Polarization, and Migration". Mol. Cell. Biol. 27 (20): 7161–75. doi:10.1128/MCB.00436-07. PMC 2168901. PMID 17682064.

- Tachibana K, Yamasaki D, Ishimoto K, Doi T (2008). "The Role of PPARs in Cancer". PPAR Res. 2008: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2008/102737. PMC 2435221. PMID 18584037.

- Peters JM, Shah YM, Gonzalez FJ (March 2012). "The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention". Nat. Rev. Cancer. 12 (3): 181–95. doi:10.1038/nrc3214. PMC 3322353. PMID 22318237.

- Wagner, Kay-Dietrich (December 12, 2019). "settings Open AccessArticle Vascular PPARβ/δ Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis and Progression". Cells. 8 (12): 1623. doi:10.3390/cells8121623. PMC 6952835. PMID 31842402.

- Brunmair B, Staniek K, Dörig J, Szöcs Z, Stadlbauer K, Marian V, Gras F, Anderwald C, Nohl H, Waldhäusl W, Fürnsinn C (November 2006). "Activation of PPAR-δ in isolated rat skeletal muscle switches fuel preference from glucose to fatty acids". Diabetologia. 49 (11): 2713–22. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0357-6. PMID 16960684.

- Girroir EE, Hollingshead HE, He P, Zhu B, Perdew GH, Peters JM (July 2008). "Quantitative expression patterns of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) protein in mice". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 371 (3): 456–61. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.086. PMC 2586836. PMID 18442472.

- Peters JM, Lee SS, Li W, Ward JM, Gavrilova O, Everett C, Reitman ML, Hudson LD, Gonzalez FJ (1993). "Growth, Adipose, Brain, and Skin Alterations Resulting from Targeted Disruption of the Mouse Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor β(δ)". Mol Cell Biol. 20 (14): 5119–28. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.14.5119-5128.2000. PMC 85961. PMID 10866668.

- Mol. Pharmacol. 77:171-184, 2010

- van der Veen JN, Kruit JK, Havinga R, Baller JF, Chimini G, Lestavel S, Staels B, Groot PH, Groen AK, Kuipers F (March 2005). "Reduced cholesterol absorption upon PPAR-δ activation coincides with decreased intestinal expression of NPC1L1". J. Lipid Res. 46 (3): 526–34. doi:10.1194/jlr.M400400-JLR200. PMID 15604518.

- Franco PJ, Li G, Wei LN (August 2003). "Interaction of nuclear receptor zinc finger DNA binding domains with histone deacetylase". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 206 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(03)00254-5. PMID 12943985. S2CID 19487189.

- Shi Y, Hon M, Evans RM (March 2002). "The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ, an integrator of transcriptional repression and nuclear receptor signaling". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (5): 2613–8. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.2613S. doi:10.1073/pnas.052707099. PMC 122396. PMID 11867749.

Further reading

- Chong HC, et al. (2009). "Regulation of epithelial–mesenchymal IL-1 signaling by PPARβ/δ is essential for skin homeostasis and wound healing". J. Cell Biol. 184 (6): 817–831. doi:10.1083/jcb.200809028. PMC 2699156. PMID 19307598.

- Tan NS, et al. (2005). "Genetic- or transforming growth factor-beta 1-induced changes in epidermal peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta expression dictate wound repair kinetics". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (18): 18163–18170. doi:10.1074/jbc.M412829200. PMID 15708854.

- Tan NS, et al. (2004). "Essential role of Smad3 in the inhibition of inflammation-induced PPARβ/δ expression". EMBO J. 23 (21): 4211–4221. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600437. PMC 524401. PMID 15470497.

- Di-Poï N; et al. (2002). "Antiapoptotic role of PPARbeta in keratinocytes via transcriptional control of the Akt1 signaling pathway". Mol. Cell. 10 (4): 721–733. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00646-9. PMID 12419217.

- Tan NS, et al. (2001). "Critical roles of PPARβ/δ in keratinocyte response to inflammation". Genes Dev. 15 (24): 3263–3277. doi:10.1101/gad.207501. PMC 312855. PMID 11751632.

- Michalik L, et al. (2001). "Impaired skin wound healing in peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR)α and PPARβ mutant mice". J. Cell Biol. 154 (4): 799–814. doi:10.1083/jcb.200011148. PMC 2196455. PMID 11514592.

External links

- PPAR+delta at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.