Palo Pinto County, Texas

Palo Pinto County is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2010 census, its population was 28,111.[1] The county seat is Palo Pinto.[2] The county was created in 1856 and organized the following year.[3]

Palo Pinto County | |

|---|---|

The Palo Pinto County courthouse in Palo Pinto. The limestone structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1997. | |

Flag | |

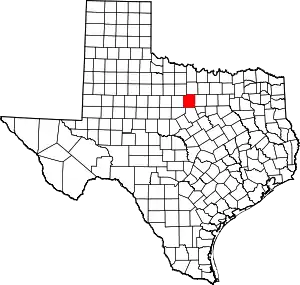

Location within the U.S. state of Texas | |

Texas's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 32°45′N 98°19′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1857 |

| Named for | Palo Pinto Creek |

| Seat | Palo Pinto |

| Largest city | Mineral Wells |

| Area | |

| • Total | 986 sq mi (2,550 km2) |

| • Land | 952 sq mi (2,470 km2) |

| • Water | 34 sq mi (90 km2) 3.4%% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 28,111 |

| • Density | 30/sq mi (10/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 11th |

| Website | www |

Palo Pinto County comprises the Mineral Wells, TX Micropolitan Statistical Area, which is part of the Dallas–Fort Worth, TX Combined Statistical Area. It is located in the Western Cross Timbers Ecoregion.

History

Native Americans

The Brazos Indian Reservation, founded by General Randolph B. Marcy in 1854, provided a safety area from warring Comanche for Delaware, Shawnee, Tonkawa, Wichita, Choctaw, and Caddo. Within the reservation, each tribe had its own village and cultivated agricultural crops. Government-contracted beef cattle were delivered each week. Citizens were unable to distinguish between reservation and nonreservation tribes, blaming Comanche and Kiowa depredations on the reservation Indians. A newspaper in Jacksboro, Texas, titled The White Man advocated removal of all tribes from North Texas.[4][5]

During December 1858, Choctaw Tom, who was a Yowani married to a Hasinai woman, who was at times an interpreter to Sam Houston, and a group of reservation Indians received permission for an off-the-reservation hunt. On December 27, Captain Peter Garland and a vigilante group charged Choctaw Tom's camp, indiscriminately murdering and injuring women and children along with the men. .[6]

Governor Hardin Richard Runnels[7] ordered John Henry Brown[8] to the area with 100 troops. An examining trial was conducted about the Choctaw Tom raid, but no indictments resulted.

In May 1859, John Baylor[9] and a number of whites confronted United States troops at the reservation, demanding the surrender of certain tribal individuals. The military balked, and Baylor retreated, but in so doing killed an Indian woman and an old man. Baylor's group was later attacked by Indians off the reservation, where the military had no authority to intervene. At the behest of terrified settlers, the reservation was abandoned that year.

County established

In 1856, the Texas State Legislature established Palo Pinto County from Bosque and Navarro Counties and named for Palo Pinto Creek. The county was organized the next year, with the town of Golconda chosen to be the seat of government. The town was renamed Palo Pinto in 1858.

Early ranching and farming years

Ranching entrepreneurs Oliver Loving[10] and Charles Goodnight,[11] who blazed the Goodnight-Loving Trail, along with Reuben Vaughan, were the nucleus of the original settlers. An 1876 area rancher meeting regarding cattle rustling became the beginnings of what is now known as the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association.

The Fence Cutting Wars in Texas lasted about 5 years, 1883–1888. As farmers and ranchers began to compete for precious land and water, cattlemen found it more difficult to feed their herds, prompting cowboys to cut through fences. Texas Governor John Ireland prodded a special assembly to order the fence cutters to cease. In response, the legislature made fence-cutting and pasture-burning crimes punishable with prison time, while at the same time regulating fencing. The practice abated with sporadic incidents of related violence in 1888.[12]

Later growth years

James and Amanda Lynch[13] first moved to the area in 1877. In digging a well on their property, they discovered the water seemed to benefit their well-being. Word spread about the water's healing powers, and people from all over came to experience the benefits. Eventually, the town of Mineral Wells[14] was platted. The Mineral Wells State Park[15] was opened to the public in 1981.

The Texas National Guard organized the 56th Cavalry Brigade in 1921, and four years later, Brigadier General Jacob F. Wolters[16] was given a grant to construct a training camp for the unit. In 1941, Camp Wolters was turned over to the United States Army. It was redesignated Wolters Air Force Base in 1951. Five years later, the base reverted to the Army as a helicopter training school . The base closed in 1973 when the helicopter school transferred to Fort Rucker in Alabama.[17]

Possum Kingdom Lake was acquired from the Brazos River Authority in 1940. The Civilian Conservation Corps constructed the facilities, and the Possum Kingdom State Park opened to the public in 1950.[18]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 986 square miles (2,550 km2), of which 952 square miles (2,470 km2) are land and 34 square miles (88 km2) (3.4%) are covered by water.[19]

Major highways

.svg.png.webp) Interstate 20

Interstate 20 U.S. Highway 180

U.S. Highway 180 U.S. Highway 281

U.S. Highway 281 State Highway 16

State Highway 16 State Highway 108

State Highway 108

Adjacent counties

- Jack County (north)

- Parker County (east)

- Hood County (southeast)

- Erath County (south)

- Eastland County (southwest)

- Stephens County (west)

- Young County (northwest)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,524 | — | |

| 1880 | 5,885 | — | |

| 1890 | 8,320 | 41.4% | |

| 1900 | 12,291 | 47.7% | |

| 1910 | 19,506 | 58.7% | |

| 1920 | 23,431 | 20.1% | |

| 1930 | 17,576 | −25.0% | |

| 1940 | 18,456 | 5.0% | |

| 1950 | 17,154 | −7.1% | |

| 1960 | 20,516 | 19.6% | |

| 1970 | 28,962 | 41.2% | |

| 1980 | 24,062 | −16.9% | |

| 1990 | 25,055 | 4.1% | |

| 2000 | 27,026 | 7.9% | |

| 2010 | 28,111 | 4.0% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 29,189 | [20] | 3.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] 1850–2010[22] 2010–2014[1] | |||

As of the census[23] of 2000, there were 27,026 people, 10,594 households, and 7,447 families residing in the county. The population density was 28 people per square mile (11/km2). There were 14,102 housing units at an average density of 15 per square mile (6/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 88.19% White, 2.32% Black or African American, 0.67% Native American, 0.53% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 6.56% from other races, and 1.71% from two or more races. 13.57% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 10,594 households, out of which 30.40% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.60% were married couples living together, 10.40% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.70% were non-families. 26.20% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.02. As of the 2010 census, there were about 2.0 same-sex couples per 1,000 households in the county.[24]

In the county, the population was spread out, with 26.00% under the age of 18, 8.20% from 18 to 24, 25.90% from 25 to 44, 23.60% from 45 to 64, and 16.40% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females there were 96.70 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.30 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $31,203, and the median income for a family was $36,977. Males had a median income of $28,526 versus $18,834 for females. The per capita income for the county was $15,454. About 12.30% of families and 15.90% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.50% of those under age 18 and 11.80% of those age 65 or over.

Communities

Cities

- Gordon

- Graford

- Mineral Wells (partly in Parker County)

- Mingus

- Strawn

Census-designated place

- Palo Pinto (county seat)

Notable people

- Steve Tyrell, singer and recording artist

- Glenn Rogers, Republican member of the Texas House of Representatives from District 60 (2021-Present)

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 81.5% 10,179 | 17.4% 2,178 | 1.1% 132 |

| 2016 | 80.7% 8,284 | 16.6% 1,708 | 2.7% 278 |

| 2012 | 79.1% 7,393 | 19.4% 1,811 | 1.6% 147 |

| 2008 | 73.5% 7,264 | 25.3% 2,499 | 1.3% 127 |

| 2004 | 71.3% 7,137 | 28.1% 2,816 | 0.6% 61 |

| 2000 | 62.4% 5,690 | 35.8% 3,263 | 1.8% 165 |

| 1996 | 42.4% 3,666 | 45.5% 3,938 | 12.1% 1,051 |

| 1992 | 30.8% 2,852 | 36.6% 3,392 | 32.7% 3,031 |

| 1988 | 53.9% 4,649 | 45.5% 3,930 | 0.6% 55 |

| 1984 | 62.8% 5,701 | 36.9% 3,349 | 0.3% 27 |

| 1980 | 48.0% 4,068 | 50.0% 4,244 | 2.0% 172 |

| 1976 | 34.0% 2,684 | 65.4% 5,170 | 0.7% 51 |

| 1972 | 69.8% 5,058 | 30.1% 2,181 | 0.1% 8 |

| 1968 | 35.3% 2,627 | 47.8% 3,552 | 16.9% 1,257 |

| 1964 | 31.6% 1,748 | 68.4% 3,791 | 0.0% 2 |

| 1960 | 46.9% 2,695 | 52.6% 3,022 | 0.4% 25 |

| 1956 | 54.2% 2,818 | 45.6% 2,369 | 0.2% 12 |

| 1952 | 51.2% 3,029 | 48.6% 2,876 | 0.2% 12 |

| 1948 | 19.4% 977 | 74.1% 3,736 | 6.6% 332 |

| 1944 | 10.1% 416 | 79.8% 3,291 | 10.2% 419 |

| 1940 | 16.5% 510 | 83.2% 2,571 | 0.3% 9 |

| 1936 | 11.9% 371 | 87.7% 2,738 | 0.5% 14 |

| 1932 | 12.5% 392 | 87.0% 2,722 | 0.5% 14 |

| 1928 | 63.3% 2,001 | 36.7% 1,161 | |

| 1924 | 18.0% 473 | 73.2% 1,926 | 8.8% 232 |

| 1920 | 15.8% 342 | 75.7% 1,645 | 8.5% 185 |

| 1916 | 6.7% 124 | 77.4% 1,431 | 15.9% 293 |

| 1912 | 3.8% 68 | 69.3% 1,231 | 26.9% 478 |

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Texas: Individual County Chronologies". Texas Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- Crouch, Carrie J: Brazos Indian Reservation from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 05 May 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- Minor, David: White Man from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 05 May 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- "Choctaw Tom". Fort Tours. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "Texas Governor Harden Richard Runnels". State of Texas. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Texas State Library and Archives Commission

- Baker, Erma: John Henry Brown from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- Thompson, Jerry: John Robert Baylor from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- "Oliver Loving". PBS.org. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Oliver Loving Descendants

- "Charles Goodnight". PBS.org. Retrieved 27 April 2010. The West Film Project and WETA

- "Fence Cutting Wars, Texas Adjutant General R.N. Steagal Letter To John Ireland March 31, 1884". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Texas State Library and Archives Commission

- "James Lynch, The Founder of Mineral Wells". Mineral Wells Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Mineral Wells Chamber of Commerce

- Sam Fenstermacher. "Mineral Wells, Texas". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Texas Escapes

- "Mineral Wells State Park". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

- "Brigadier General Jacob F. Wolters". Fort Wolters. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Brian N. Bagnall

- "Camp. Wolters". Fort Wolters. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Brian N. Bagnall

- "Possum Kingdom State Park". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved 27 April 2010. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "Texas Almanac: Population History of Counties from 1850–2010" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- Where Same-Sex Couples Live, June 26, 2015, retrieved July 6, 2015

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

External links

- Palo Pinto County government's website

- Historic Palo Pinto County materials hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Palo Pinto County from the Handbook of Texas Online