Throckmorton County, Texas

Throckmorton County is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2010 census, its population was 1,641.[1] Its county seat is Throckmorton.[2] The county was created in 1858 and later organized in 1879.[3] It is named for William Throckmorton, an early Collin County settler.[4] Throckmorton County is one of six[5] prohibition, or entirely dry, counties in the state of Texas.

Throckmorton County | |

|---|---|

The Throckmorton County Courthouse | |

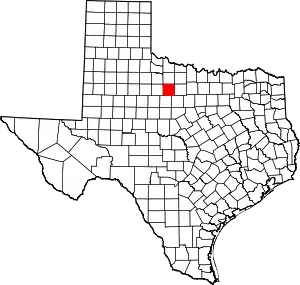

Location within the U.S. state of Texas | |

Texas's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 33°11′N 99°13′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1879 |

| Named for | William Throckmorton |

| Seat | Throckmorton |

| Largest town | Throckmorton |

| Area | |

| • Total | 915 sq mi (2,370 km2) |

| • Land | 913 sq mi (2,360 km2) |

| • Water | 2.9 sq mi (8 km2) 0.3%% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 700 |

| • Density | 1.8/sq mi (0.7/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 19th |

| Website | www |

History

The Spanish explorer Pedro Vial is considered to be the earliest European to travel through what is now known as Throckmorton County. Vial passed between the Clear Fork and Main Fork of the Brazos River in 1786 while searching for a direct route between San Antonio and Santa Fe. No other major activity is recorded in the county until 1849, when Captain Randolph B. Marcy, commander of a U.S. military escort expedition led by Lieutenant J. E. Johnson, passed through the county.

In 1837, the Republic of Texas established Fannin County, which included the area now known as Throckmorton County. In 1858, Throckmorton County was officially established. Williamsburg was designated as county seat. The county was named in honor of Dr. William E. Throckmorton, an early north Texas pioneer and the father of James W. Throckmorton, who later became governor of Texas. Organization of the county was delayed until 1879, when Throckmorton was named the county seat.

In 1854, Captain Marcy returned to the county in search of suitable locations for a reservation for Texas Indians. He surveyed and established the tract of land that became known as the Comanche Indian Reservation, which is adjacent to the Clear Fork of the Brazos River in the county. The reservation consisted of approximately 18,576 acres (75.17 km2) of land extending well out from both sides of the river. The location was ideal because it provided plenty of running water and hunting opportunities. Marcy also met with Sanaco and the Tecumseh leaders of the southern band of Comanche Indians in an attempt to persuade them to move to the reservation, which they began doing in 1855. In January 1856, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston established Camp Cooper (named after Samuel Cooper) on the banks of the Clear Fork to protect the reservation. Captain Robert E. Lee served as commander of the camp from April 9, 1856, to July 22, 1857. In 1859, persons living on the Comanche Indian Reservation were uprooted and moved to the Oklahoma Indian Territory. In 1861, a few months before the start of the Civil War, Camp Cooper was abandoned by federal troops in the face of building political tension between north and south.

From 1847 until the start of the Civil War, several settlers moved into the county, living mostly in the vicinity of Camp Cooper. When the camp was abandoned, most of the settlers moved east into a line of forts that offered protection from the Northern Comanche Indians.

In 1858, the Butterfield Overland Mail stage line began operating with two relay stations in Throckmorton County. One, called Franz's Station, and another was Clear Fork of the Brazos station on the east bank of the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, a short distance above its confluence with Lambshead Creek, in southwestern Throckmorton County.

Following the Civil War, Fort Griffin was established in 1867 along the Clear Fork of the Brazos River directly south of the Throckmorton - Shackleford County line. With federal troops in the area, most of the old settlers returned to the county and many new ones arrived. The first settlements were in areas along the Clear Fork, where the natural environment was best and wildlife was abundant. Vast herds of buffalo roamed in the areas, with buffalo hunters being headquartered at Fort Griffin. The first settlers were cattlemen who used the open range at will and moved cattle northward along the Great Western Cattle Trail. Later, farmers moved into the survey area and homesteaded on small tracts of land.

Federal troops abandoned Fort Griffin in 1881. This signaled the end of the region's frontier era.

Glenn Reynolds was the first sheriff of Throckmorton County, Texas. Later, he moved to Arizona and was elected sheriff of Globe, Gila County, Arizona. On November 2, 1889, while transporting Apache Indian prisoners to Yuma State Prison, he and Deputy Sheriff Williams Holmes, were overpowered outside of Kelvin, Arizona and killed by them. One of these prisoners was the infamous Apache Kid.

.[6]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 915 square miles (2,370 km2), of which 913 square miles (2,360 km2) are land and 2.9 square miles (7.5 km2) (0.3%) are covered by water.[7]

Major highways

U.S. Highway 183

U.S. Highway 183 U.S. Highway 283

U.S. Highway 283 U.S. Highway 380

U.S. Highway 380 State Highway 79

State Highway 79 State Highway 222

State Highway 222

Adjacent counties

- Baylor County (north)

- Young County (east)

- Stephens County (southeast)

- Shackelford County (south)

- Haskell County (west)

- Archer County (northeast)

- Knox County (northwest)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 124 | — | |

| 1880 | 711 | — | |

| 1890 | 902 | 26.9% | |

| 1900 | 1,750 | 94.0% | |

| 1910 | 4,563 | 160.7% | |

| 1920 | 3,589 | −21.3% | |

| 1930 | 5,253 | 46.4% | |

| 1940 | 4,275 | −18.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,618 | −15.4% | |

| 1960 | 2,767 | −23.5% | |

| 1970 | 2,205 | −20.3% | |

| 1980 | 2,053 | −6.9% | |

| 1990 | 1,880 | −8.4% | |

| 2000 | 1,850 | −1.6% | |

| 2010 | 1,641 | −11.3% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 1,501 | [8] | −8.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] 1850–2010[10] 2010–2014[1] | |||

2010 census

As of the census of 2010, there were 1,641 people. There were 1,079 housing units, 358 of which were vacant. The racial makeup of the county was 94.8% White (1,555 people), 0.1% Black or African American (2 people), 0.7% Native American (1 person), 0.4% Asian (7 people), 2.6% from other races (43 people), and 0.8% from two or more races (13 people). 9.3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race (152 people).

2000 census

As of the census[11] of 2000, there were 1,850 people, 765 households, and 534 families residing in the county. The population density was 2 people per square mile (1/km2). There were 1,066 housing units at an average density of 1 per square mile (0/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 92.11% White, 0.05% Black or African American, 0.43% Native American, 0.05% Asian, 5.57% from other races, and 1.78% from two or more races. 9.35% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 765 households, out of which 29.20% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.80% were married couples living together, 8.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.10% were non-families. 28.00% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.60% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.20% under the age of 18, 5.70% from 18 to 24, 22.90% from 25 to 44, 25.70% from 45 to 64, and 20.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females there were 97.20 males. For every 100 women age 18 and over, there were 93 men.

The median income for a household in the county was $28,277, and the median income for a family was $34,563. Men had a median income of $22,837 versus $19,485 for women. The per capita income for the county was $17,719. About 11.40% of families and 13.50% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.60% of those under age 18 and 7.50% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

Republican Drew Springer, Jr., a businessman from Muenster in Cooke County, has represented Throckmorton County in the Texas House of Representatives since 2013. Springer defeated Throckmorton County rancher Trent McKnight in the Republican runoff election held on July 31, 2012. McKnight won 49% of the vote on May 29, 2012, and missed securing the House seat by 188 votes.[12]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 90.2% 806 | 9.2% 82 | 0.7% 6 |

| 2016 | 88.5% 715 | 10.4% 84 | 1.1% 9 |

| 2012 | 86.1% 700 | 13.4% 109 | 0.5% 4 |

| 2008 | 80.1% 671 | 19.8% 166 | 0.1% 1 |

| 2004 | 76.0% 656 | 23.4% 202 | 0.6% 5 |

| 2000 | 72.2% 608 | 27.1% 228 | 0.7% 6 |

| 1996 | 48.9% 360 | 38.7% 285 | 12.5% 92 |

| 1992 | 38.2% 389 | 39.4% 401 | 22.4% 228 |

| 1988 | 45.6% 455 | 53.5% 534 | 0.9% 9 |

| 1984 | 59.9% 586 | 39.6% 388 | 0.5% 5 |

| 1980 | 48.9% 444 | 50.1% 455 | 1.0% 9 |

| 1976 | 35.0% 356 | 64.8% 658 | 0.2% 2 |

| 1972 | 61.8% 568 | 37.9% 348 | 0.3% 3 |

| 1968 | 29.9% 317 | 58.3% 618 | 11.9% 126 |

| 1964 | 21.9% 247 | 78.1% 883 | |

| 1960 | 39.0% 442 | 60.8% 689 | 0.3% 3 |

| 1956 | 41.4% 466 | 58.2% 656 | 0.4% 5 |

| 1952 | 44.6% 586 | 55.4% 728 | |

| 1948 | 5.6% 63 | 91.6% 1,026 | 2.8% 31 |

| 1944 | 6.4% 76 | 81.9% 970 | 11.7% 138 |

| 1940 | 12.2% 138 | 87.8% 995 | |

| 1936 | 12.2% 132 | 87.6% 949 | 0.2% 2 |

| 1932 | 9.2% 95 | 90.6% 932 | 0.2% 2 |

| 1928 | 69.8% 703 | 30.2% 304 | |

| 1924 | 24.2% 174 | 75.0% 539 | 0.8% 6 |

| 1920 | 14.5% 72 | 80.1% 399 | 5.4% 27 |

| 1916 | 2.4% 10 | 79.3% 333 | 18.3% 77 |

| 1912 | 1.5% 4 | 93.0% 252 | 5.5% 15 |

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Texas: Individual County Chronologies". Texas Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hct05

- "TABC Local Option Elections General Information". www.tabc.state.tx.us. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- McCrummen, Stephanie (3 October 2011). "At Rick Perry's Texas hunting spot, camp's old racially charged name lingered". The Washington Post.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- "Texas Almanac: Population History of Counties from 1850–2010" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "State Rep. Springer announces district tour July 30". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, July 16, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-07-31.