Badlands National Park

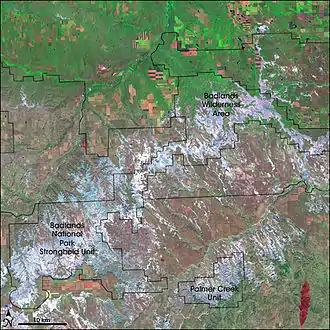

Badlands National Park (Lakota: Makȟóšiča[3]) is an American national park located in southwestern South Dakota. The park protects 242,756 acres (379.3 sq mi; 982.4 km2)[1] of sharply eroded buttes and pinnacles, along with the largest undisturbed mixed grass prairie in the United States. The National Park Service manages the park, with the South Unit being co-managed with the Oglala Lakota tribe.[4]

| Badlands National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

Badlands National Park | |

Location in the United States  Location in South Dakota | |

| Location | South Dakota, United States |

| Nearest city | Rapid City, South Dakota |

| Coordinates | 43°45′N 102°30′W |

| Area | 242,756 acres (982.40 km2)[1] |

| Established | January 29, 1939 as a National Monument November 10, 1978 as a National Park |

| Visitors | 1,008,942 (in 2018)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Badlands National Park |

.jpg.webp) |

| Southwestern South Dakota |

|---|

| Sculptures |

| Geologic and natural history |

| Mountains |

| Caves |

| Forests and wildernesses |

| Lakes |

| Scenic byways |

The Badlands Wilderness protects 64,144 acres (100.2 sq mi; 259.6 km2) of the park as a designated wilderness area,[5] and is one site where the black-footed ferret, one of the most endangered mammals in the world, was reintroduced to the wild.[6] The South Unit, or Stronghold District,[4] includes sites of 1890s Ghost Dances,[7] a former United States Air Force bomb and gunnery range,[8] and Red Shirt Table, the park's highest point at 3,340 feet (1,020 m).[9]

Authorized as Badlands National Monument on March 4, 1929, it was not established until January 25, 1939. Badlands was redesignated a national park on November 10, 1978.[10] Under the Mission 66 plan, the Ben Reifel Visitor Center was constructed for the monument in 1957–58. The park also administers the nearby Minuteman Missile National Historic Site. The movies Dances with Wolves (1990) and Thunderheart (1992) were partially filmed in Badlands National Park.[11]

History

Native Americans

For 11,000 years, Native Americans have used this area for their hunting grounds. Long before the Lakota were the little-studied paleo-Indians, followed by the Arikara people. Their descendants live today in North Dakota as a part of the Three Affiliated Tribes. Archaeological records combined with oral traditions indicate that these people camped in secluded valleys where fresh water and game were available year-round. Eroding out of the stream banks today are the rocks and charcoal of their campfires, as well as the arrowheads and tools they used to butcher bison, rabbits, and other game. From the top of the Badlands Wall, they could scan the area for enemies and wandering herds. If hunting was good, they might hang on into winter, before retracing their way to their villages along the Missouri River. The Lakota people were the first to call this place "mako sica" or "land bad." Extreme temperatures, lack of water, and the exposed rugged terrain led to this name. French-Canadian fur trappers called it "les mauvaises terres pour traverser," or "bad lands to travel through."[12] By one hundred and fifty years ago, the Great Sioux Nation consisting of seven bands including the Oglala Lakota, had displaced the other tribes from the northern prairie.

The next great change came toward the end of the 19th century as homesteaders moved into South Dakota. The U.S. government stripped Native Americans of much of their territory and forced them to live on reservations. In the fall and early winter of 1890, thousands of Native Americans, including many Oglala Sioux, became followers of the Indian prophet Wovoka. His vision called for the native people to dance the Ghost Dance and wear Ghost shirts, which would be impervious to bullets. Wovoka had predicted that the white man would vanish and their hunting grounds would be restored. One of the last known Ghost Dances was conducted on Stronghold Table in the South Unit of Badlands National Park. As winter closed in, the ghost dancers returned to Pine Ridge Agency. The climax of the struggle came in late December 1890. Headed south from the Cheyenne River, a band of Minneconjou Sioux crossed a pass in the Badlands Wall. Pursued by units of the U.S. Army, they were seeking refuge in the Pine Ridge Reservation. The band, led by Chief Spotted Elk,[13] was finally overtaken by the soldiers near Wounded Knee Creek in the Reservation and ordered to camp there overnight. The troops attempted to disarm Big Foot's band the next morning. Gunfire erupted. Before it was over, nearly three hundred Indians and thirty soldiers lay dead. The Wounded Knee Massacre was the last major clash between Plains Indians and the U.S. military until the advent of the American Indian Movement in the 1970s, most notably in the 1973 standoff at Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

Wounded Knee is not within the boundaries of Badlands National Park. It is located approximately 45 miles (72 km) south of the park on Pine Ridge Reservation. The U.S. government and the Oglala Lakota Nation have agreed that this is a story to be told by the Oglala of Pine Ridge and Minneconjou of Standing Rock Reservation. The interpretation of the site and its tragic events are held as the primary responsibility of these survivors.

Fossil hunters

The history of the White River Badlands as a significant paleontological resource goes back to the traditional Native American knowledge of the area. The Lakota found large fossilized bones, fossilized seashells and turtle shells. They correctly assumed that the area had once been under water, and that the bones belonged to creatures which no longer existed.[14] Paleontological interest in this area began in the 1840s. Trappers and traders regularly traveled the 300 miles (480 km) from Fort Pierre to Fort Laramie along a path which skirted the edge of what is now Badlands National Park. Fossils were occasionally collected, and in 1843 a fossilized jaw fragment collected by Alexander Culbertson of the American Fur Company found its way to a physician in St. Louis by the name of Hiram A. Prout.

In 1846, Prout published a paper about the jaw in the American Journal of Science in which he stated that it had come from a creature he called a Paleotherium. Shortly after the publication, the White River Badlands became popular fossil hunting grounds and, within a couple of decades, numerous new fossil species had been discovered in the White River Badlands. In 1849, Dr. Joseph Leidy published a paper on an Oligocene camel and renamed Prout's Paleotherium, Titanotherium prouti. By 1854 when he published a series of papers about North American fossils, 84 distinct species had been discovered in North America – 77 of which were found in the White River Badlands. In 1870 a Yale professor, O. C. Marsh, visited the region and developed more refined methods of extracting and reassembling fossils into nearly complete skeletons. From 1899 to today, the South Dakota School of Mines has sent people almost every year and remains one of the most active research institutions working in the White River Badlands. Throughout the late 19th century and continuing today, scientists and institutions from all over the world have benefited from the fossil resources of the White River Badlands. The White River Badlands have developed an international reputation as a fossil-rich area. They contain the richest deposits of Oligocene mammals known, providing a glimpse of life in the area 33 million years ago.

List of fossil animals

- Alligator (Crocodilian)

- Archaeotherium (Entelodont)

- Dinictis (Nimravid)

- Eporeodon (Oreodont)

- Eusmilus (Nimravid)

- Hoplophoneus (Nimravid)

- Hyaenodon (Creodont)

- Hyracodon (Running Rhino)

- Ischyromys (Ground Squirrel-like Rodent)

- Leptomeryx (Tragulid)

- Merycoidodon (Oreodont)

- Mesohippus (Horse)

- Metamynodon (Aquatic Rhino)

- Miniochoerus (Oreodont)

- Poebrotherium (Camel)

- Subhyracodon (Rhinoceros)

Homesteaders

Aspects of American homesteading began before the end of the American Civil War; however, it did not affect the Badlands until the 20th century. Then, many hopeful farmers traveled to South Dakota from Europe or the eastern United States to try to seek out a living in the area. In 1929, the South Dakota Dept. of Agriculture published an advertisement to lure settlers to the state. On this map they called the Badlands, "The Wonderlands", promising "...marvelous scenic and recreational advantages". The standard size for a homestead was 160 acres (0.3 sq mi; 0.6 km2). Being in a semi-arid, wind-swept environment, this proved far too small of a holding to support a family. In 1916, in the western Dakotas, the size of a homestead was increased to 640 acres (1.0 sq mi; 2.6 km2). Cattle grazed the land, and crops such as winter wheat and hay were cut annually. However, the Great Dust Bowl events of the 1930s, combined with waves of grasshoppers, proved too much for most of the settlers of the Badlands. Houses, which had been built out of sod blocks and heated by buffalo chips, were abandoned.

Military use of Stronghold District

As part of the World War II effort, the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) took possession of 341,726 acres (533.9 sq mi; 1,382.9 km2) of land on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home of the Oglala Sioux people, for a gunnery range. Included in this range was 337 acres (0.5 sq mi; 1.4 km2) from the Badlands National Monument. This land was used extensively from 1942 through 1945 as an air-to-air and air-to-ground gunnery range including both precision and demolition bombing exercises. After the war, portions of the bombing range were used as an artillery range by the South Dakota National Guard. In 1968, most of the range was declared excess property by the USAF. Although 2,500 acres (3.9 sq mi; 10.1 km2) were retained by the USAF (but are no longer used) the majority of the land was turned over to the National Park Service.

Firing took place within most of the present-day Stronghold District. Land was bought or leased from individual landowners and the Tribe in order to clear the area of human occupation. Old car bodies and 55 gallon drums painted bright yellow were used as targets. Bulls-eyes 250 feet (76 m) across were plowed into the ground and used as targets by bombardiers. Small automatic aircraft called "target drones" and 60-by-8-foot (18 by 2 m) screens dragged behind planes served as mobile targets. Today, the ground is littered with discarded bullet cases and unexploded ordnance.

In the 1940s, 125 families were forcibly relocated from their farms and ranches, including Dewey Beard, a survivor of the Wounded Knee Massacre. Those that remained nearby recall times when they had to dive under tractors while out cutting hay to avoid bombs dropped by planes miles outside of the boundary. In the town of Interior, both a church and the building housing the current post office were struck by six inch (152 mm) shells through the roof. Pilots operating out of Ellsworth Air Force Base near Rapid City found it a real challenge to determine the exact boundaries of the range. There were no civilian casualties. However, at least a dozen flight crew personnel lost their lives in plane crashes.

The Stronghold District of Badlands National Park, co-managed by the National Park Service and the Oglala Lakota Tribe, is a 133,300-acre (208.3 sq mi; 539.4 km2) area. Deep draws, high tables and rolling prairie are characteristic of these lands occupied by the earliest plains hunters, the paleo-Indians, and the Lakota Nation.

Legislative and administrative history

On March 4. 1929, President Calvin Coolidge signed Public Law No. 1021, authorizing the Badlands National Monument in South Dakota.[15][16] The legislation’s conditions for eventual proclamation included, the acquisition of privately owned land within the proposed boundaries of the monument, and the construction of a 30 mile highway throughout the park.[17] The Badlands National Monument became the seventy-seventh monument within the National Park Service a decade after its original authorization, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the enacting proclamation on January 24. 1939. The monument was later renamed “Badlands National Park” in 1978.[18] [19]

The Badlands National Monument was established in order to preserve the natural scenery and educational resources within its boundaries. The bill authorized specific scientific and educational institutions to excavate within the monument in the pursuit of educational, geological, and zoological observation. The bill includes a portion highlighting the potential for fossil excavation in the monument's geological formations.[20]

Badlands National Park Superintendents[21]

- John E. Suter(1949–1953)

- John A. Rutter (1953–1957)

- George H. Sholly (1958–1959)

- Frank E. Sylvester (1960–1960)

- John W. Jay (1960–1962)

- Frank A. Hjort (1963–1967)

- John R. Earnst (1967–1970)

- Cecil D. Lewis, JR (1970–1974)

- James E. Jones (1974–1979)

- Gilbert E. Blinn (1979–1985)

- James L. Monheiser (1985–1985)

- Donald A. Falvey (1985–1987)

- Lloyd P. Kortge (1987–1987)

- Irvin L. Mortenson (1987–1996)

- Bill Supernaugh (1997–2004)[22]

- Paige Baker (2005–2010)[23]

- Eric Brunnemann (2010–2015)[24]

- Mike Pflaum (2015–)[25]

Wildlife

Animals that inhabit the park include:[4] badger, bighorn sheep, bison, black-billed magpie, black-footed ferret, black-tailed prairie dog, bobcat, coyote, elk, mule deer, pronghorn, prairie rattlesnake, porcupine, swift fox, and white-tailed deer.[26]

- Wildlife in the park

Prairie dogs

Prairie dogs Bighorn sheep

Bighorn sheep Bison bull

Bison bull

In 1963, 50 bison from Theodore Roosevelt National Park were released into the parkland. The herd has grown to over 1,000 animals.[27]

Visitor services

Badlands National Park has two campgrounds for overnight visits - Cedar Pass and Sage Creek Campgrounds. Cedar Pass lodge offers accommodations in modern cabins and full-service dining. [28] The Ben Reifel Visitor Center within the park offers a bookstore, special programs, and museum exhibits. The White River Visitors center in the park's South Unit offers information about the regions Lakota heritage.

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Badlands National Park has a cold semi-arid climate (Bsk).

| Climate data for Interior, SD (elevation 2440 ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

75 (24) |

85 (29) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

109 (43) |

114 (46) |

110 (43) |

106 (41) |

97 (36) |

84 (29) |

72 (22) |

114 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 36.0 (2.2) |

40.4 (4.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

62.6 (17.0) |

72.8 (22.7) |

83 (28) |

91.4 (33.0) |

90.9 (32.7) |

80.7 (27.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

48.9 (9.4) |

38.4 (3.6) |

63.5 (17.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 13.1 (−10.5) |

16.4 (−8.7) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

36.1 (2.3) |

46.8 (8.2) |

56.3 (13.5) |

62.8 (17.1) |

61.1 (16.2) |

50.7 (10.4) |

38.8 (3.8) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

15.9 (−8.9) |

37.4 (3.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −28 (−33) |

−31 (−35) |

−23 (−31) |

3 (−16) |

20 (−7) |

32 (0) |

42 (6) |

35 (2) |

25 (−4) |

2 (−17) |

−21 (−29) |

−31 (−35) |

−31 (−35) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.33 (8.4) |

0.45 (11) |

0.94 (24) |

1.98 (50) |

3.05 (77) |

3.10 (79) |

2.22 (56) |

1.54 (39) |

1.32 (34) |

1.20 (30) |

0.49 (12) |

0.34 (8.6) |

16.96 (429) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.6 (9.1) |

4.8 (12) |

5.6 (14) |

3.8 (9.7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

3.2 (8.1) |

4.2 (11) |

25.8 (65.4) |

| Source: http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?sd4184 | |||||||||||||

Gallery

Buttes and pinnacles

Buttes and pinnacles Boardwalk to the Windows

Boardwalk to the Windows Door Trail

Door Trail A view of the park from an airplane to the north.

A view of the park from an airplane to the north.

Current issues and challenges

The Badlands National Park has been impacted by the rise of oil and gas pipelines/drilling, the debate over Native American land rights, and fossil loss due to criminal activity.

Oil pipelines/drilling

The Badlands National Park faces growing encroachment from oil and gas companies hoping to transport fossil fuels throughout regions of South Dakota. Pipelines are associated with environmental risks; breaches and or breaks in the system have the potential to negatively impact the quality of life for surrounding ecosystems and wildlife. Additionally, the Badlands is quickly being surrounded by drilling and fracking projects.[29][30][31]

Challenges to land rights

The Badlands National Park also faces debate over the federal claims to the land once inhabited by the Oglala Lakota Sioux tribe. Supporters of Oglala Sioux reparations argue against the U.S. government's seizure and management over sacred Native American land. The Badlands National Park began taking steps to reserve part of the park's southern unit for management by the tribe's members, creating jobs and returning ownership to those re-located out during America's Manifest Destiny, however this creation of the “Tribal National Park” has yet to come to pass.[32]

Fossil depletion

The Badlands National Park was first established as a national monument in order to protect the abundance of fossils within the land’s natural stone structures. Since the park's founding, visitors and fossil poachers/hunters have been looting the park’s fossils to keep for sentimental and scientific value or to sell for profit.[33]

References

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Ullrich, Jan, ed. (2011). New Lakota Dictionary (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Lakota Language Consortium. p. 855. ISBN 978-0-9761082-9-0. LCCN 2008922508.

- "Badlands Visitor Guide: The official newspaper of Badlands National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Badlands Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- "Badlands Visitor Guide" (PDF). National Park Service. 2008. p. 2. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- "Badlands National Park". Rand McNally. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

The cultural centerpiece of this section is the Stronghold Table, where the Oglala Sioux danced the Ghost Dance for the last time in 1890.

- "Pine Ridge Gunnery Range/Badlands Bombing Range". South Dakota Department of Environment & Natural Resources. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- "U.S. National Park High Points". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- "The National Parks: Index 2009–2011". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- Maddrey, Joseph (2016). The Quick, the Dead and the Revived: The Many Lives of the Western Film. McFarland. Page 184. ISBN 9781476625492.

- "Badlands - Frequently Asked Questions". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- Chief Spotted Elk on u-s-history.com

- "How Did Badlands National Park Get Its Name?". USA Today. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Tennant, Brad (May 22, 2017). On This Day in South Dakota History. ISBN 9781625857644.

- "Part 2:Listing of National Park System Areas by State". Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- "LEGISLATION FOR PARK ESTABLISHMENT". National Park Service.

- Hellman, Paul (February 14, 2006). Historical Gazetter of the United States. p. 1,000. ISBN 1135948593.

- Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior. June 30, 1929. p. 38.

- "Legislation for Park Establishment". National Park Service.

- "National Park Service: Historic Listings of NPS Officials". www.nps.gov.

- Ray, Charles (August 18, 2003). "Trouble over the Badlands". www.hcn.org. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- staff, Journal. "Badlands National Park superintendent to retire". Rapid City Journal Media Group.

- Eilperin, Juliet (June 23, 2013). "In the Badlands, a tribe helps buffalo make a comeback" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- Interior, Mailing Address: 25216 Ben Reifel Road; Us, SD 57750 Phone:433-5361 Contact. "Mike Pflaum Selected as Superintendent of Badlands National Park - Badlands National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- Ruiz, Santi (September 13, 2020). "Bring Back the Bison". Yahoo News. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "Bison Bellows: Badlands National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Campgrounds - Badlands National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- LightHawk (April 27, 2015). "A defender of North Dakota's badlands wonders if it's time to leave". Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Bachmann, Daria (November 6, 2018). "National Parks at Risk From Trump Administration's Energy Agenda". The Revelator. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- DALRYMPLE, AMY (November 11, 2017). "Badlands landowner seeks to protect historic landscape from oil impacts". Bismarck Tribune. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Zach, Elizabeth (December 14, 2016). "In the Badlands, Where Hope for the Nation's First Tribal Park Has Faded". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Miller, Steve (September 20, 2003). "Officials fight fossil hunting". Rapid City Journal. Retrieved April 30, 2020.