St. Louis Park, Minnesota

St. Louis Park is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 45,250 at the 2010 census.[5] It is a first-ring suburb immediately west of Minneapolis. Other adjacent cities include Edina, Golden Valley, Minnetonka, Plymouth, and Hopkins.

St. Louis Park | |

|---|---|

St. Louis Park City Hall | |

| Motto(s): "Experience Life in the Park" | |

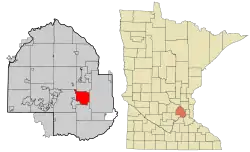

Location of the city of St. Louis Park within Hennepin County, Minnesota | |

| Coordinates: 44°56′54″N 93°20′53″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Hennepin |

| Founded | 1852 |

| Incorporated | November 19, 1886 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jake Spano |

| Area | |

| • City | 10.85 sq mi (28.09 km2) |

| • Land | 10.63 sq mi (27.53 km2) |

| • Water | 0.22 sq mi (0.56 km2) |

| Elevation | 899 ft (274 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • City | 49,069 |

| • Estimate (2020)[3] | 49,069 |

| • Rank | MN: 20th |

| • Density | 4,578.66/sq mi (1,767.85/km2) |

| • Metro | 3,524,583 (US: 16th) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 55416, 55426, 55424 |

| Area code(s) | 952 |

| FIPS code | 27-57220 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0650797[4] |

| Website | City of St. Louis Park |

St. Louis Park is the birthplace or childhood home of movie directors Joel and Ethan Coen, musician Peter Himmelman, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, former Senator Al Franken, songwriter Dan Israel, guitarist Sharon Isbin, writer Pete Hautman, football coach Marc Trestman, and film director Joe Nussbaum. Baseball announcer Halsey Hall also lived there.

The Pavek Museum of Broadcasting, which has a major collection of antique radio and television equipment, is also in the city. Items range from radios produced by local manufacturers to the Vitaphone system used to cut discs carrying audio for the first "talkie", The Jazz Singer.

The Coen brothers set their 2009 film A Serious Man in St. Louis Park circa 1967. It was important to the Coens to find a neighborhood of original-looking suburban rambler homes as they would have appeared in St. Louis Park in the mid-1960s, and after careful scouting they opted to film scenes in a neighborhood of nearby Bloomington,[6][7] as well as at St. Louis Park's B'nai Emet Synagogue, which was later sold and converted into a school.

History

Early developments

The 1860s village that became St. Louis Park was originally known as Elmwood, which today is a neighborhood inside the city. In August 1886, 31 people signed a petition asking county commissioners to incorporate the Village of St. Louis Park. The petition was officially registered on November 19, 1886.

The name "St. Louis Park" was derived from the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway that ran through the area; the word "Park" was added to avoid confusion with St. Louis, Missouri.[8]

In 1892, lumber baron Thomas Barlow Walker and a group of wealthy Minneapolis industrialists incorporated the Minneapolis Land and Investment Company to focus industrial development in Minneapolis. Walker's company also began developing St. Louis Park for industrial, commercial and residential use.

Generally, development progressed outward from the original village center at the intersection of the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway with Wooddale Avenue. But Minneapolis soon expanded as far west as France Avenue, and its boundary may have continued to move westward had it not been for St. Louis Park's 1886 incorporation.

By 1893, St. Louis Park's downtown had three hotels, and many newly arrived companies surrounded downtown. Around 1890, the village had more than 600 industrial jobs, mostly associated with agriculture implement manufacturing.

The financial panic of 1893 altered developers' plans and put a damper on the village's growth. Walker left St. Louis Park to pursue other business ventures.p

In 1899, St. Louis Park became the home to the Peavey–Haglin Experimental Concrete Grain Elevator, the world's first concrete, tubular grain elevator, which provided an alternative to combustible wooden elevators. Despite being nicknamed "Peavey's Folly" and dire predictions that the elevator would burst like a balloon when the grain was drawn off, the experiment worked and concrete elevators have been used ever since.

Suburban boom

At the end of World War I, only seven scattered retail stores operated in St. Louis Park because streetcars provided easy access to shopping in Minneapolis. Between 1920 and 1930, the population doubled from 2,281 to 4,710. Vigorous homebuilding occurred in the late 1930s to accommodate the pent-up need created during the Depression. With America's involvement in World War II, however, all development came to a halt.

Explosive growth came after World War II. In 1940, 7,737 people lived in St. Louis Park. By 1955, more than 30,000 new residents had joined them. From 1940 to 1955, growth averaged 6.9 persons moving into St. Louis Park every day. Sixty percent of St. Louis Park's homes were built in a single burst of construction from the late 1940s to the early 1950s.

Residential development was closely followed by commercial developers eager to bring goods and services to these new households. In the late 1940s, Minnesota's first shopping center — the 30,000-square-foot (2,800 m2) Lilac Way — was constructed on the northeast corner of Excelsior Boulevard and Highway 100. (The Lilac Way shopping center was torn down in the late 1980s to make way for redevelopment.) Miracle Mile shopping center, built in 1950, and Knollwood Mall, which opened in 1956, remain open today.

In the late 1940s, a group of 11 former army doctors opened the St. Louis Park Medical Center in a small building on Excelsior Boulevard. The medical center merged with Methodist Hospital and today is Park Nicollet Health Services, part of HealthPartners, the second-largest medical clinic in Minnesota (after Rochester's Mayo Clinic).

During the period between 1950 and 1956, 66 new subdivisions were recorded to make room for 2,700 new homes. In 1953 and 1954, the final two parcels — Kilmer and Shelard Park — were annexed. These parcels (originally in Minnetonka) came to St. Louis Park because of their ability to provide sewer and water service.

From village to city

In 1954, voters approved a home rule charter that gave an overwhelmed St. Louis Park the status of a city. That enabled the city to hire a city manager to assume some of the duties handled by the part-time city council. Several bridges built during that time are now being repaired or razed.

In those days, the primary concerns were the physical planning of St. Louis Park, updating zoning and construction codes, expanding sewer and water systems, paving streets, acquiring park land and building schools.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.86 square miles (28.13 km2), of which 10.64 square miles (27.56 km2) is land and 0.22 square miles (0.57 km2) is water.[9]

Interstate 394, U.S. Highway 169, and Minnesota State Highways 7 and 100 are four of the main routes in St. Louis Park.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 499 | — | |

| 1900 | 1,325 | 165.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,743 | 31.5% | |

| 1920 | 2,281 | 30.9% | |

| 1930 | 4,710 | 106.5% | |

| 1940 | 7,737 | 64.3% | |

| 1950 | 22,644 | 192.7% | |

| 1960 | 43,310 | 91.3% | |

| 1970 | 48,883 | 12.9% | |

| 1980 | 42,931 | −12.2% | |

| 1990 | 43,787 | 2.0% | |

| 2000 | 44,126 | 0.8% | |

| 2010 | 45,250 | 2.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 48,662 | [3] | 7.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 2018 Estimate[11] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 45,250 people, 21,743 households, and 10,459 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,252.8 inhabitants per square mile (1,642.0/km2). There were 23,285 housing units at an average density of 2,188.4 per square mile (844.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.3% White, 7.5% African American, 0.5% Native American, 3.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.8% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.3% of the population.

There were 21,743 households, of which 22.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.6% were married couples living together, 9.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 51.9% were non-families. 40.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.05 and the average family size was 2.82.

The median age in the city was 35.4 years. 18.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 36.4% were from 25 to 44; 24% were from 45 to 64; and 13% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.8% male and 52.2% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 44,126 people, 20,782 households, and 10,557 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,122.5 persons per square mile (1,592.3/km2). There were 21,140 housing units at an average density of 1,975.0 per square mile (762.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.91% White, 4.37% African American, 0.45% Native American, 3.21% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 1.28% from other races, and 1.72% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.93% of the population.

There were 20,782 households, out of which 22.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.3% were married couples living together, 8.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 49.2% were non-families. 37.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.08 and the average family size was 2.81.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 18.8% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 37.7% from 25 to 44, 20.2% from 45 to 64, and 14.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.3 males. The median income for a household in the city was $49,260, and the median income for a family was $63,182. Males had a median income of $40,561 versus $32,447 for females. The per capita income for the city was $28,970. About 3.0% of families and 5.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.2% of those under age 18 and 6.7% of those age 65 or over.

Russian and Jewish populations

The city has a relatively high Jewish population for Minnesota, and is home to the Sabes Jewish Community Center and several synagogues including Beth El Synagogue and Kenesseth Israel Congregation. It is estimated that around 38% of Jews in the greater Minneapolis area live in St. Louis Park.[12][13] Due, in part, to mass immigration from former-Soviet states, Saint Louis Park has a large Russian population around its Aquila area. The Russian language is the second most spoken language in the city after English, and the Hennepin County Library's St. Louis Park location has an extensive Russian language section.[12][14]

Government

St. Louis Park operates under the Council/Manager form of government. An elected City Council sets the policy and overall direction for the city. Then city workers, under the direction of a professional city manager carry out council decisions and provide day-to-day city services. The city manager is accountable to the City Council. St. Louis Park voters elect the mayor and six (two at-large and four ward) City Council members to four-year terms. The mayor and at-large council members represent all residents; the ward council members are primarily responsible for representing their ward constituents.

Politics

St. Louis Park is in Minnesota's 5th congressional district, represented by Ilhan Omar, a Democrat. The town was placed in this district, which includes traditionally liberal segments of Minneapolis, in the redistricting after the 1990 census. Before that, St. Louis Park had been part of the 3rd congressional district, along with Edina and other more conservative suburbs. The 3rd district was represented by Republicans Clark MacGregor and William Frenzel from 1961 until 1991.

Education

Public schools

The St. Louis Park School District, Independent School District 283, is home to seven public schools serving about 4,200 students in grades K–12 students. St. Louis Park is the only school district in Minnesota in which every public school has been recognized as a Blue Ribbon School of Excellence by the U.S. Department of Education.

In the 1960s, the proportion of school-age children in St. Louis Park was much higher than it is now, although the population has not changed much. Due to declining enrollment over the years, there have been several changes to schools in the district:

- Ethel Baston Elementary School was closed; its building is now occupied by Groves Academy, a private school.

- Fern Hill Elementary School was closed; its building is now occupied by Torah Academy of Minneapolis, a private school.

- Oak Hill Elementary School opened in 1950 and closed in 1967. Oak Hill enrollment was limited to students in grades one and two, as well as one special education class.

- Park Knoll Elementary School was demolished to expand the Knollwood Mall.

- Brookside Elementary School, Lenox Elementary School, and Eliot Elementary School were closed as public school buildings: Brookside was procured by a developer who converted the school into condominiums; Lenox Community Center has the SLP Senior Program and preschool on the main floor, with nonprofits on the second; Eliot was sold to a developer who tore it down to build apartment buildings in 2014.

- Central Community Center, formerly Central Junior High School, now houses the Park Spanish Immersion School and other ISD 283 programs, including Early Childhood Special Education (ECSE), Early Childhood Family Education (ECFE), and Community Education programs including Gymnastics and Swimming. For some years, there were two junior high schools in St. Louis Park. The one now called St. Louis Park Middle School was then Westwood Junior High School.

- Peter Hobart Elementary School and Aquila Elementary School became Peter Hobart Primary Center and Aquila Primary Center, serving only grades K through 3, and Susan Lindgren Elementary School and Cedar Manor Elementary School became intermediate schools serving only grades 4 through 6.

- In 1970, St. Louis Park Senior High School served only grades 10 through 12 and had about 2500 students; now it serves grades 9 through 12 and serves about 1350 students.

- In 2010, Cedar Manor Elementary School was closed. Peter Hobart Elementary, Susan Lindgren Elementary, Aquila Elementary, and Park Spanish Immersion were converted to Kindergarten through 5th grade schools, with grade 6 moving to St. Louis Park Junior High.[15]

- In 2019, Park Spanish Immersion Elementary School moved operations to the Cedar Manor building.

| Schools in the Saint Louis Park School District | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Elementary Schools (K–5) | Junior High (6–8) | Senior High (9–12) | |

| Peter Hobart Elementary School | Susan Lindgren Elementary School | St. Louis Park Junior High School | St. Louis Park Senior High School |

| Aquila Elementary School | Park Spanish Immersion School | ||

Athletic teams

St. Louis Park's athletic teams are called the Orioles. The school colors are orange and black. In 2005 the school moved out of the Classic Lake Conference and into the North Suburban Conference. In 2013, the school moved out of the North Suburban Conference and into the Metro West Conference.

The school won the boys' state basketball tournament in 1962 under coach Lloyd Holm, and had a resurgence in boys' basketball in the 1970s under coach August Schmidt.[16]

The girls' basketball teams won two state championships in 1986 and 1990 under head coach Phil Frerk. The school also has a synchronized swimming program.

For many years, a fixture at Park athletic events was the school dance line, the Parkettes, who served as cheerleaders for the Minnesota Vikings from 1964 to 1983.

Athletes to come out of St. Louis Park include former NBA player and current Timberwolves broadcaster Jim Peterson (1980), NFL coach Marc Trestman (1974), current NHL player Erik Rasmussen (1995), Junior All-American cross-country skier Andrew J. Cheesebro, and current Sioux City Explorer T. J. Bohn (1998). 1965 graduate Bob Stein was an All-American end at the University of Minnesota and the youngest player ever to play in a Super Bowl, for the Kansas City Chiefs. He later served as the President of the Minnesota Timberwolves from 1987 to 1994. Former Minnesota Vikings and Tennessee Titans President Jeff Diamond is a 1971 St. Louis Park graduate.

Private schools

- Academy of Whole Learning

- Benilde-St. Margaret's School is a Catholic, co-educational school serving students in grades 7–12

- Groves Academy

- Heilicher Minneapolis Jewish Day School, formerly Minneapolis Jewish Day School, Abbreviated as HMJDS, is attached to the Sabes JCC, is a private K–8 school. Teaches Hebrew in language and text and offers Spanish as an after school program. The school team is the Lions. Their colors are Navy and Gold.

- Metropolitan Open School

- Torah Academy of Minneapolis

Businesses

There are over 2,700 businesses in St. Louis Park, including:

- Travelers Express/MoneyGram, deposit banking functions — 450 employees[17]

- Benilde-St. Margaret's School — 200 employees

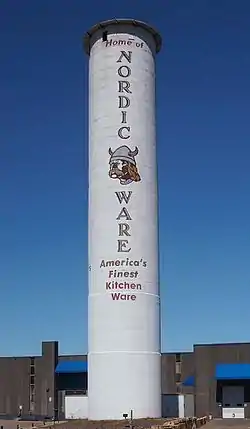

- Nordic Ware (also known as Northland Aluminum Products), which introduced the Bundt cake in about 1950, household cooking equipment — 135 employees

The city employs 252 people and the school district (District #283) employs about 762.

City Vision Project

On February 12, 2006, the City of St. Louis Park embarked on its second City Vision project. This project is an initiative led by the city to determine the path it will take in the next 5–10 years. The original project, undertaken ten years ago, led to the construction of the Excelsior and Grand development.

Following the February 12 meeting, the city is looking into several areas that were of common interest among those in attendance. Those included balanced housing, improved transportation options, the reworking of the Minnesota Highway 7 intersections, and a gathering place for young people.

The Parkwifi project was an attempt to provide wireless internet service throughout the city, but this project was ultimately canceled in April 2007 because of the failure of the installation contractor to fulfil any of the launch dates.

Notable people

- Michael Birawer, artist.

- The Coen Brothers, filmmakers.

- Charles Foley (1930–2013), inventor of the game Twister (lived in a special care facility in St. Louis Park at the time of his death from Alzheimer's disease)[18]

- Al Franken (b. 1951), U.S. Senator, comedian[19]

- Thomas Loren Friedman (b. 1953), journalist and author.

- Sharon Isbin, guitarist, professor at the Juilliard School.

- Ade Olufeko, international curator.

- Norman Ornstein, political scientist.

- Michael J. Sandel, political philosopher.

- Marc Trestman, football coach.

- George Floyd, truck driver, security guard, rapper, community leader, father, and victim of killing of George Floyd, which set off 2020 Black Lives Matter protests

- Owen Husney, manager who discovered and first signed Prince to Warner Brothers

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 3, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "In Twin Cities, Coen brothers shoot from heart". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008.

- Judy Poseley, The Park, City of St. Louis Park, 1976; copy accessed from "St. Louis Park inventory" file, State Historic Preservation Office in the Minnesota History Center.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- The Jewish Community in St Louis Park. In: St. Louis Park Historical Society.

- "Historic Jewish St. Louis Park Tour". Archived from the original on August 9, 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 10, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 18, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "SPORTS TIMELINE | St Louis Park Historical Society". slphistory.org. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- "Contact Us." MoneyGram. Retrieved on May 11, 2010.

- Chawkins, Steve (July 10, 2013). "Chuck Foley dies at 82; co-invented Twister party game" Archived July 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times.

- "AL FRANKEN – St Louis Park Historical Society". slphistory.org. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for St. Louis Park, Minnesota. |